Hinduism in Bangladesh

Hinduism is the second largest religious affiliation in Bangladesh, according to the Bangladesh population and housing for 2011 Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, approximately 12.49 million people responded that they were Hindus, constituting 8.5% out of the total 149.77 million population.[1] In terms of population, Bangladesh is the third largest Hindu populated country of the world, just after India and Nepal. The total Hindu population in Bangladesh exceeds the population of many Muslim majority countries like Yemen, Jordan, Tajikistan, Syria, Tunisia, Oman, and others.[2] Also the total Hindu population in Bangladesh is roughly equal to the total population of Greece and Belgium.[3]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| All over the Bangladesh, predominantly in Sylhet, Chittagong and Khulna. | |

| Sylhet | 2,154,214 (17.8%) |

| Khulna | 2,580,637 (16.45%) |

| Rangpur | 2,453,418 (15.54%) |

| Chittagong | 3,595,512 (12.65%) |

| Dhaka | 3,512,190 (9.64%) |

| Religions | |

| Hinduism | |

| Languages | |

| Sanskrit (Sacred) Bangla, Hindi and Urdu | |

| Hinduism by country |

|---|

|

| Full list |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 9,546,240 | — |

| 1911 | 9,939,825 | +4.1% |

| 1921 | 10,176,030 | +2.4% |

| 1931 | 10,466,988 | +2.9% |

| 1941 | 11,759,160 | +12.3% |

| 1951 | 9,239,603 | −21.4% |

| 1961 | 9,379,669 | +1.5% |

| 1974 | 9,673,048 | +3.1% |

| 1981 | 10,570,245 | +9.3% |

| 1991 | 11,178,866 | +5.8% |

| 2001 | 11,379,000 | +1.8% |

| 2011 | 12,492,427 | +9.8% |

| *The Census of 1971 was delayed due to the Liberation War of Bangladesh Source: God Willing: The Politics of Islamism in Bangladesh by Ali Riaz, p. 63 | ||

In nature, Bangladeshi Hinduism closely resembles the forms and customs of Hinduism practiced in the neighboring Indian state of West Bengal, with which Bangladesh (at one time known as East Bengal) was united until the partition of India in 1947.[4] The vast majority of Hindus in Bangladesh are Bengali Hindus.[5]

The Goddess (Devi) – usually venerated as Durga or Kali – is widely revered, often alongside her consort Shiva. The worship of Shiva has generally found adherents among the higher castes in Bangladesh. Worship of Vishnu (typically in the form of his Avatars or incarnation Rama or Krishna) more explicitly cuts across caste lines by teaching the fundamental oneness of humankind in spirit. Vishnu worship in Bengal expresses the union of the male and female principles in a tradition of love and devotion. This form of Hindu belief and the Sufi tradition of Islam have influenced and interacted with each other in Bengal. Both were popular mystical movements emphasizing the personal relationship of religious leaders and disciples instead of the dry stereotypes of the brahmins or the ulama. As in Bengali Islamic practice, worship of Vishnu frequently occurs in a small devotional society (shomaj). Both use the language of earthly love to express communion with the divine. In both traditions, the Bengali language is the vehicle of a large corpus of mystical literature of great beauty and emotional impact.

In Bangladeshi Hinduism ritual bathing, vows, and pilgrimages to sacred rivers, mountains, and shrines are common practices. An ordinary Hindu will worship at the shrines of Muslim pirs, without being concerned with the religion to which that place is supposed to be affiliated. Hindus revere many holy men and ascetics conspicuous for their bodily mortifications. Some believe that they attain spiritual benefit merely by looking at a great holy man. Durga Puja, held in September–October, is the most important festival of Bangladeshi Hindus and it is widely celebrated across Bangladesh. Thousands of pandals (mandaps) are set up in various cities, towns, and villages to mark the festival. Other festivals are Kali Puja, Janmashtami, Holi, Saraswati Puja, Shivratri and Rathayatra, the most popular being the century-old Dhamrai Rathayatra.

The principle of ahimsa is expressed in almost universally observed rules against eating beef. By no means are all Bangladeshi Hindus vegetarians, but abstinence from all kinds of meat is regarded as a "higher" virtue. The Priestly Caste Brahmin (pronounced Brahmon in Bengali) Bangladeshi Hindus, unlike their counterparts elsewhere in South Asia, eat fish and chicken. This is similar to the Indian state of West Bengal, where Hindus also consume fish, eggs, chicken, and mutton.There are also non-Bengali Hindus in Bangladesh, majority of the Hajong, Rajbongshi people and Tripuris in Bangladesh are Hindus.[6]

Demographics

| Year | Percentage (%) | Hindu Population | Total population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 33.00 | 9,546,240 | 28,927,626 | |

| 1911 | 31.50 | 9,939,825 | 31,555,363 | Before partition |

| 1921 | 30.60 | 10,176,030 | 33,254,607 | |

| 1931 | 29.40 | 10,466,988 | 35,604,189 | |

| 1941 | 28.00 | 11,759,160 | 41,999,221 | |

| 1951 | 22.05 | 9,239,603 | 42,062,462 | During Pakistan period |

| 1961 | 18.50 | 9,379,669 | 50,804,914 | |

| 1974 | 13.50 | 9,673,048 | 71,478,543 | After independence of Bangladesh |

| 1981 | 12.13 | 10,570,245 | 87,120,487 | |

| 1991 | 10.51 | 11,178,866 | 106,315,583 | |

| 2001 | 9.20 | 11,379,000 | 123,151,871 | |

| 2011 | 8.54 | 12,492,427 | 149,332,484 |

Source: Census of India 1901-1941, Census of East Pakistan 1951-1961, Bangladesh Government Census 1974-2011,[7][8][9] Report (2019-20) on international religious freedom: Bangladesh.[10]

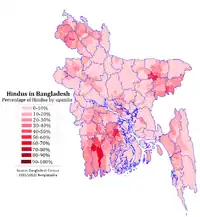

According to the 2001 Bangladesh census, there were around 11.37 million Hindus in Bangladesh constituting 9.2% of the population, which at the time was 124.35 million. The 2011 census, approximately 12.49 million people responded that they were Hindus, constituting 8.5% of the total 149.77 million.[11] Hindus in Bangladesh in the late 2000s were almost evenly distributed in all regions, with large concentrations in Gopalganj, Dinajpur, Sylhet, Sunamganj, Mymensingh, Khulna, Jessore, Chittagong and parts of Chittagong Hill Tracts. In the capital city of Dhaka, Hindus are the second-largest religious community after the Muslims and the largest concentration of Hindus can be found in and around Shankhari Bazaar of the old city.

In 2013, Amnesty International reported that the rise of more explicitly Islamist political formations in Bangladesh during the 1990s had resulted in many Hindus being intimidated or attacked, and that fairly substantial numbers were leaving the country for India.[12]

In 1901, Hindus constitute 33% of East Bengal population then what is now known as Bangladesh, but during the next successive years the Hindu percentage have came down to 29.4% in 1931 that is before partition of Bengal when East Bengal was still a part of Indian Union under British rule. In 1941 the Hindus formed about 28% of the population, which declined to 22.05% in 1951 after India's partition, as rich and upper-caste Hindus migrated to India after the Partition of India in 1947. The wealthy Hindus who migrated lost their land and assets through the East Bengal Evacuee Act and the poor and middle-class Hindus that were left behind became targets of discrimination through new laws. At the outbreak of the 1965 India-Pakistan war, the Defense of Pakistan Ordinance and later the Enemy (Custody and Registration) Order II, through which the Hindus were labeled as the "enemy" and their property expropriated by the state.[13][14][15] Since then, it has dropped by about half. Through a combination of mass exodus and genocide in the 1971 Bangladesh atrocities by the Pakistan Army during the Bangladesh Liberation War, this represents a loss of around 20 million Bangladeshi Hindus and their direct heirs and reflects one of the largest displacements of population-based on ethnic or religious identity in recent history. 1974 census of Bangladesh showed that the population of Hindus had fallen to 13.5%. Even after independence, the Hindus were branded "Indian stooges" and untrustworthy citizens.[13] A significant driver of Hindu emigration has been the Enemy Property Act, later renamed as the Vested Property Act, through which the Bangladesh Government has been able to appropriate the property of around 40% of the existing Bangladeshi Hindu population (according to Dr. Abul Barkat of Dhaka University). A significant portion of the middle-class, urban Hindu population left the region that is now Bangladesh immediately after the partition in 1947 when East Pakistan came into existence. Many of these East Bengali refugees went on to contribute actively to Indian society after their migration. In 1971, during the Liberation War of Bangladesh from Pakistan, a similar scenario happened.

Since 1971, the Hindu percentage has continued to decline, forming 8.96% of the population as of 2011. The fall in the share of total population has been attributed to outward migration, and the fertility rate for Hindus remaining consistently lower than Muslims (2.1 versus 2.3 as of 2014).[16][17]

Hindu population by administrative divisions

| Division | Percentage (%) | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Barisal | 11.7% | 974,103 |

| Chittagong | 12.65% | 3,595,512 |

| Dhaka | 9.64% | 3,512,190 |

| Khulna | 16.45% | 2,580,637 |

| Rajshahi | 12.09% | 2,234,820 |

| Rangpur | 15.54% | 2,453,418 |

| Sylhet | 17.8% | 2,154,214 |

| Mymensingh | 4.22% | 479,814 |

Hinduism in Bangladesh by decades[11]

| Year | Percent | Increase |

|---|---|---|

| 1901 | 33% | - |

| 1911 | 31.5% |

-1.5% |

| 1921 | 30.6% |

-0.9% |

| 1931 | 29.4% |

-1.2% |

| 1941 | 28% |

-1.4% |

| 1951 | 22% |

-6% |

| 1961 | 18.5% | -3.5% |

| 1974 | 13.5% | -5% |

| 1981 | 12.1% | -1.4% |

| 1991 | 10.5% | -1.6% |

| 2001 | 9.6% | -0.9% |

| 2011 | 8.5% | -1.1% |

The Hindu population in Bangladesh has undergone steady erosion over the years, from 28% in 1940 to 8.96% in 2011, with especially two periods of alarmingly sharp decline—the first around the time of Partition and the second during the 1971 Bangladesh War that resulted in the Liberation of Bangladesh. However, even after the emergence of Bangladesh, the Hindu community has declined—from 13.5% in 1974 to 8.96% in 2011—a nearly 33% decline, which is humungous in demographic terms.[20]

Projections

From 1964 to 2013, around 11.3 million Hindus left Bangladesh due to religious persecution and discrimination, as stated by Dhaka university economist Abul Barkat. On average 632 Hindus left the country each day and 230,612 annually as reported by him. From his 30-year-long research, Barkat found that the exodus mostly took place during military governments after independence.[21] Abul Barkat (Dhaka University based economist) also state's: that there should have been 28.7 million Hindus in the year 2013 instead of 12.2 million,” Or, to put it another way, Hindus should accounted for 16-18% of Bangladesh’s population, not 9.7% as they do currently.[22]

According to the Pew research center, Bangladesh will have 14.47 million Hindus by 2050 and will comprise 7.3% of the country's population.[23]

| Year | Total Population | Hindu population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2050 | 198,219,000 | 14,470,000 | 7.3% |

Hindu Temples

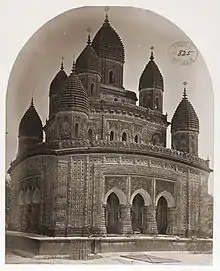

Hindu temples and shrines are more or less distributed all across the country. The Kantaji Temple is an elegant example of an 18th-century temple. The most important temple in terms of prominence is the Dhakeshwari Temple, located in Dhaka. This temple along with other Hindu organizations arranges Durga Puja and Krishna Janmaashtami very prominently. The other main temples of Dhaka are the Ramakrishna Mission, Joy Kali Temple, Laxmi Narayan Mandir, Swami Bagh Temple and Siddheswari Kalimandir.

Built in the early 19th century, Kal Bhairab Temple at Brahmanbaria holds the largest deity of Shiva in the country. Other notable Hindu temples and ashrams of Bangladesh are Chandranath Temple, Adinath Temple, Sugandha, Jeshoreshwari Kali Temple, Pancha Ratna Govinda Temple, Bhabanipur Shaktipeeth, Chatteshwari Temple, Dhamrai Jagannath Rath, Puthia Temple Complex, Kantajew Temple, Comilla Jagannath Temple, Kaliyajeu Temple, Shri Shail, Bishwanath Temple, Boro Kali Bari Temple, Muktagacha Shiva Temple, Shyamsundar Temple, Chandrabati Temple, Lalmai Chandi Temple, Jorbangla Temple, Sonarang Twin Temples, Jagannath Temple, Pabna, Temple of King Kangsa Narayan, Barodi Lokenath Ashram, Sri Satyanarayan Seva Mandir, Sri Angan, Wahedpur Giri Dham, Ramkrishna Sevashram at Chittagong, Ram Thakur Ashram etc.[28]

Many Hindu temples have suffered from the implementation of the Vested Property Act through which land and moveable property has been confiscated by agents acting on behalf of successive governments. Hindu temples are also high-risk areas during communal disturbances (most recently in 1990, 1992, and 2001) when it has often been necessary to call the army to protect sensitive locations.

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Shiva Temple, Puthia, Rajshahi.

Shiva Temple, Puthia, Rajshahi..jpg.webp) Dhakeshwari Temple, Dhaka is the largest Hindu temple in Bangladesh.

Dhakeshwari Temple, Dhaka is the largest Hindu temple in Bangladesh.

.JPG.webp)

Roth Yatra procession.

Roth Yatra procession. Durga Pujan in Dhaka.

Durga Pujan in Dhaka.

Controversial Hindu Marriage law

Hindu family law governs the personal life of Hindus in Bangladesh.There is no known limit for the number of wives a Hindu man can take in Bangladesh so polygamy for Hindu man is legal in Bangladesh.[29]

"Under Bangladesh Hindu (civil) law, men may have multiple wives, but there are officially no options for divorce," the report said.

Women are also prohibited from inheriting property under the civil laws for Hindus, the report said.

A survey conducted during the year by Research Initiatives in Bangladesh and MJF showed that 26.7 percent of Hindu men and 29.2 percent of Hindu women would like to obtain a divorce but did not do so because of existing laws," it added.[30]

Community Issues

The Hindu community has many similar issues as the predominantly Muslim community of Bangladesh. These include women's rights, dowry, poverty, unemployment, and others. Issues unique to the Hindu community include maintenance of Hindu culture and temples in Bangladesh. Small sects of Islamists constantly try to politically and socially isolate the Hindus of Bangladesh.[31] Because Hindus of Bangladesh are scattered across all areas (except in Narayanganj), they cannot unite politically. However, Hindus became sway voters in various elections. Hindus have usually voted in large mass for Bangladesh Awami League and communist parties, as these are the only parties which have a nominal commitment to secularism;[32] the alternatives are the increasingly pro-Islamist centrist parties such as the Bangladesh Nationalist Party and Jatiya Party (which both incorporate Muslim identity into their version of Bangladeshi nationalism) or the outright Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh (an offshoot of the Pakistan-based Jamaat-e-Islami) which seeks to establish Islamic law under which there would be separate provisions for Hindus as non-Muslims. However, Hindus, in general, maintain cordial relationships with liberal Muslims and they even participate in each other's festivals such as Durga Puja and Eid al-Fitr.

Bangladesh Liberation and 1971 Bangladesh atrocities (1971)

The Bangladesh Liberation War resulted in one of the largest genocides of the 20th century. While estimates of the number of casualties were 3,000,000, it is reasonably certain that Hindus bore a disproportionate brunt of the Pakistan Army's onslaught against the Bengali population of what was East Pakistan. The Pakistani Army killed as many as 2.4 million Bengali Hindus during the Liberation War, and most of the Bengali Hindu-owned businesses were permanently destroyed. The historic Ramna Kali Temple in Dhaka and the century-old Rath at Dhamrai were demolished and burned down by the Pakistani Army.

An article in Time magazine dated 2 August 1971, stated "The Hindus, who account for three-fourths of the refugees and a majority of the dead, have borne the brunt of the Muslim military hatred."[33]

Senator Edward Kennedy wrote in a report that was part of United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations testimony dated 1 November 1971, "Hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community who have been robbed of their lands and shops, systematically slaughtered, and in some places, painted with yellow patches marked "H". All of this has been officially sanctioned, ordered and implemented under martial law from Islamabad". In the same report, Senator Kennedy reported that 80% of the refugees in India were Hindus and according to numerous international relief agencies such as UNESCO and World Health Organization, the number of East Pakistani refugees at its peak in India was close to 10 million. Given that the Hindu population in East Pakistan was around 11 million in 1971, this suggests that up to 8 million, or more than 70% of the Hindu population had fled the country.

The Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Sydney Schanberg covered the start of the war and wrote extensively on the suffering of the East Bengalis, including the Hindus both during and after the conflict. In a syndicated column "The Pakistani Slaughter That Nixon Ignored", he wrote about his return to liberated Bangladesh in 1972. "Other reminders were the yellow "H"s the Pakistanis had painted on the homes of Hindus, particular targets of the Muslim army" (by "Muslim army", meaning the Pakistan Army, which had targeted Bengali Muslims as well), (Newsday, 29 April 1994).

The initial post-independence period (1972–75)

In the first constitution of the newly independent country, secularism and equality of all citizens irrespective of religious identity were enshrined. On his return to liberated Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in his first speech to the nation, specifically recognized the disproportionate suffering of the Hindu population during the Bangladesh Liberation War. On a visit to Kolkata, India in February 1972, Mujib visited the refugee camps that were still hosting several million Bangladeshi Hindus and appealed to them to return to Bangladesh and to help to rebuild the country.

Despite the public commitment of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his government to re-establishing secularism and the rights of non-Muslim religious groups, two significant aspects of his rule remain controversial as relates to the conditions of Hindus in Bangladesh. The first was his refusal to return the premises of the Ramna Kali Mandir, historically the most important temple in Dhaka, to the religious body that owned the property. This centuries-old Hindu temple was demolished by the Pakistan army during the Bangladesh Liberation War, and around one hundred devotees were murdered. Under the provisions of the Enemy Property Act, it was determined that ownership of the property could not be established as there were no surviving members to claim inherited rights, and the land was handed over to the Dhaka Club.

Secondly, state-authorized confiscation of Hindu owned property under the provisions of the Enemy Property Act was rampant during Mujib's rule, and as per the research conducted by Abul Barkat of Dhaka University, the Awami League party of Sheikh Mujib was the largest beneficiary of Hindu property transfer in the past 35 years of Bangladeshi independence. This was enabled considerably because of the particular turmoil and displacement suffered by Bangladeshi Hindus, who were the primary target of the Pakistan army's genocide, as well documented by international publications such as Time magazine and the New York Times, and by the declassified Hamoodur Rahman Commission report. With almost 8 million displaced Hindus and more than 200,000 Hindu victims of genocide, it was difficult to establish direct ownership of property within legally specified timeframes. This caused much bitterness among Bangladeshi Hindus, particularly given the public stance of the regime's commitment to secularism and communal harmony.

Largely because of these and other factors, such as the lack of attention to the Human Rights Violations of Hindus in the country, the Hindu population of Bangladesh started to decline through migration.[34]

Rahman and Hussein regimes (1975–1990)

President Ziaur Rahman abandoned the constitutional provision for secularism and began to introduce Islamic symbolism in all spheres of national life (such as official seals and the constitutional preamble). Zia brought back the multi-party system thus allowing organizations such as Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh (an offshoot of the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami in Pakistan) to regroup and contest elections.

In 1988 President Hussein Mohammed Ershad declared Islam to be the State Religion of Bangladesh. Though the move was protested by students and left-leaning political parties and minority groups, to this date neither the regimes of the BNP or Awami League has challenged this change and it remains in place.[35]

In 1990, the Ershad regime was widely blamed for negligence (and some human rights analysis allege active participation) in the anti-Hindu riots following the Babri Mosque incident in India, the largest communal disturbances since Bangladesh independence, as a means of diverting attention from the rapidly increasing opposition to his rule.[36][37] Many Hindu temples, Hindu neighbourhoods and shops were attacked and damaged including, for the first time since 1971, the Dhakeshwari temple. The atrocities were brought to the West's attention by many Bangladeshis, including Taslima Nasrin and her book Lajja which translated into English means "shame".

Return to democracy (1991–present)

_in_Bangladesh.jpg.webp)

Hindus were first attacked in mass in 1992 by Islamic fundamentalists. More than 200 temples were destroyed. Hindus were attacked and many women were raped and killed.[38] The events were widely seen as a repercussion against the razing of the Babri Mosque in India.[39] Taslima Nasrin wrote her novel Lajja (The Shame) based on this persecution of Hindus by Islamic extremists. The novel centers on the suffering of the patriotic anti-Indian and pro-Communist Datta family, where the daughter is raped and killed while financially they end up losing everything.

Prominent political leaders frequently fall back on "Hindu bashing" in an attempt to appeal to extremist sentiment and to stir up communal passions. In one of the most notorious utterances of a mainstream Bangladeshi figure, the immediate past Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, while the leader of the opposition in 1996, declared that the country was at risk of hearing "uludhhwani" (a Hindu custom involving women's ululation) from mosques, replacing the azan (Muslim call to prayer) (e.g., see Agence-France Press report of 18 November 1996, "Bangladesh opposition leader accused of hurting religious sentiment").[40]

After the election of 2001, when a right-wing coalition including two Islamist parties (Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh and Islami Oikya Jote) led by the pro-Islamic right wing Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) came to power, many minority Hindus and liberal secularist Muslims were attacked by a section of the governing regime. Thousands of Bangladeshi Hindus were believed to have fled to neighbouring India[41] to escape the violence unleashed by activists sympathetic to the new government. Many Bangladeshi Muslims played an active role in documenting atrocities against Hindus during this period.[40][42]

The new government also clamped down on attempts by the media to document alleged atrocities against non-Muslim minorities following the election. Severe pressure was put on newspapers and other media outside of government control through threats of violence and other intimidation. Most prominently, the Muslim journalist and human rights activist Shahriyar Kabir was arrested on charges of treason on his return from India where he had been interviewing Hindu refugees from Bangladesh; this was[43] by the Bangladesh High Court and he was subsequently freed.

The fundamentalists and right-wing parties such as the BNP and Jatiya Party often portray Hindus as being sympathetic to India, and transferring economic resources to India, contributing to a widespread perception that Bangladeshi Hindus are disloyal to the state. Also, the right-wing parties claim the Hindus to be backing the Awami League.[12] As widely documented in international media, Bangladesh authorities have had to increase security to enable Bangladeshi Hindus to worship freely[44] following widespread attacks on places of worship and devotees.

After recent bombings in Bangladesh by the Islamic fundamentalists, the government has taken steps to strengthen the security during various minority celebrations, especially during Durga Puja and Rathayatra.

In October 2006, the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom published a report titled 'Policy Focus on Bangladesh,' which said that since its last election, 'Bangladesh has experienced growing violence by religious extremists, intensifying concerns expressed by the country's religious minorities'. The report further stated that Hindus are particularly vulnerable in a period of rising violence and extremism, whether motivated by religious, political or criminal factors, or some combination. The report noted that Hindus had multiple disadvantages against them in Bangladesh, such as perceptions of dual loyalty concerning India and religious beliefs that are not tolerated by the politically dominant Islamic Fundamentalists of the BNP. Violence against Hindus has taken place "in order to encourage them to flee in order to seize their property". The previous reports of the Hindu American Foundation were acknowledged and confirmed by this non-partisan report.[45][46]

On 2 November 2006, USCIRF criticized Bangladesh for continuing persecution of minority Hindus. It also urged the Bush administration to get Dhaka to ensure the protection of religious freedom and minority rights before Bangladesh's next national elections in January 2007.[45][46]

In 2013, the International Crimes Tribunal indicted several Jamaat members for war crimes against Hindus during the 1971 Bangladesh atrocities. In retaliation, violence against Hindu minorities in Bangladesh was instigated by the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. The violence included the looting of Hindu properties and businesses, the burning of Hindu shops and homes, rape and abductions of Hindu women, and vandalizing and desecrating the Hindu temples.[47]

According to the BJHM report in 2017 alone, at least 107 people of the Hindu community were killed and 31 fell victims to enforced disappearance 782 Hindus were either forced to leave the country or threatened to leave. Besides, 23 were forced to get converted into other religions. At least 25 Hindu women and children were raped, while 235 temples and statues were vandalized during the year. The total number of atrocities happened with the Hindu community in 2017 is 6474.[48] During the 2019 Bangladesh elections, eight houses belonging to Hindu families on fire in Thakurgaon alone.[49]

In April 2019, two idols of Hindu goddesses, Lakshmi and Saraswati, have been vandalized by unidentified miscreants at a newly constructed temple in Kazipara of Brahmanbaria.[50] In the same month, several idols of Hindu gods in two temples in Madaripur Sadar Upazila which were under construction were desecrated by miscreants.[51]

Political representation

Even after the decline of the Hindu population in Bangladesh from 13.5% in 1974, just after the independence, Hindus were at around 9.2% of the population in 2001 according to government estimates following the census. However, Hindus accounted for only four members of the 300 member parliament following the 2001 elections through direct election; this went up to five following a by-election victory in 2004. Significantly, of the 50 seats reserved for women that are directly nominated by the Prime Minister, not a single one was allotted to a Hindu. The political representation is not at all satisfactory and several Hindu advocacy groups in Bangladesh have demanded a return to a communal electorate system as existed during the Pakistan period, to enable a more equitable and proportionate representation in parliament, or a reserved quota since the persecution of Hindus has continued since 1946.[52]

Despite their dwindling population, Hindus still yield considerable influence because of their geographical concentration in certain regions. They form a majority of the electorate in at least two parliamentary constituencies (Khulna-1 and Gopalganj-3) and account for more than 25% in at least another thirty. For this reason, they are often the deciding factor in parliamentary elections where victory margins can be extremely narrow. It is also frequently alleged that this is a prime reason for many Hindus being prevented from voting in elections, either through intimidating actual voters or through exclusion in voter list revisions.[53]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

|

Prominent Bangladeshi Hindus

Politics

- Comrade Moni Sinha, founding General Secretary of Bangladesh Communist Party

- Pulin De

- Chitta Ranjan Dutta

- Trailokyanath Chakravarty

- Suranjit Sengupta

Current ministers

Current members of Jatiya Sangsad

Current 11th Jatiya Sangsad has 18 Hindu MP [56]

Justice

- Surendra Kumar Sinha, 21st Chief Justice of Bangladesh

- Krishna Debnath, justice of the High Court Division

- Gobinda Chandra Tagore, justice of the High Court Division

- Bhabani Prasad Singha, justice of the High Court Division

- Ashish Ranjan Daash, justice of the High Court Division

- Bhishmadev Chakrabortty, justice of the High Court Division

Sports

- Brojen Das, swimming

- Bikash Ranjan Das, cricket

- Alok Kapali, cricket

- Tapash Baishya, cricket

- Dhiman Ghosh, cricket

- Biplob Bhattacharjee, football

- Rajani Kanta Barman, football

- Mithun Chowdhury, football

- Soumya Sarkar, Cricket

- Liton Das, Cricket

- Shuvagata Hom, Cricket

- Pinak Ghosh, cricket

- Rony Talukdar, cricket

- Debabrata Barua, cricket

- Narayan Chandra, cricket

- Taposh Ghosh, cricket

- Sumon Saha, cricket

- Sanjit Saha, cricket

- Subashis Roy, cricket

- Kochi Rani Mondal, kabaddi

- Topu Barman, football

Music

- Subir Nandi, singer

- Tapan Chowdhury (singer)

- Shuvro Dev, singer

- Rathindranath Roy, singer

- Kumar Bishwajit, pop singer

- Ustad Barin Mazumder, classical singer

- Bappa Mazumder, singer, and son of Ustad Barin Mazumder

- Ajit Roy, Rabindra Sangeet singer

- Bijoy Sarkar, music composer and singer

Cinema

- Apu Biswas

- Shabnam (Bengali actress)

- Sumita Devi

- Amalendu Biswas

- Aruna Biswas

- Jyotsna Biswas

- Subhash Dutta

- Aparna Ghosh

- Anju Ghosh

- Chitralekha Guho

- Ashish Kumar Louho

- Ramendu Majumdar

- Bidya Sinha Saha Mim

- Jayanta Chattopadhyay

- Prabir Mitra

- Narayan Ghosh Mita

- Puja Cherry Roy

- Chanchal Chowdhury

- Bappy Chowdhury

Literature and Journalism

Arts

Business

- Ranada Prasad Saha (Philanthropist, founder of Kumudini College and Kumudini Hospital at Mirzapur Upazila, Tangail)

Academic

Martyrs in 1971

Science and Technology

See also

Sources

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.- Nasrin, Taslim (2014). Lajja. Penguin Books. ISBN 9-789-351-18643-4. OCLC 1132343651.

- Benkin, Richard L. (2014). A Quiet Case of Ethnic Cleansing (The Murder of Bangladesh's Hindus). Akshaya Prakashan. ISBN 9-788-188-64352-3.

- Rummel, Rudolf J. (1998). Statistics of Democide (Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900). LIT Publications. ISBN 9-783-825-84010-5.

- Ahmed, Babu; Chowdhury, Nazly (2005). Alam, Md. Shafiqul (ed.). Selected Hindu Temples of Bangladesh. University of Michigan: UNESCO, Dhaka. ISBN 9-789-843-21778-3.

References

- "Bangladesh's Hindus number 1.7 crore, up by 1 p.c. in a year: report". The Hindu. PTI. 23 June 2016. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 9 February 2021.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "[Analysis] Are there any takeaways for Muslims from the Narendra Modi government?". DNA. 27 May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- Haider, M. Moinuddin; Rahman, Mizanur; Kamal, Nahid (6 May 2019). "Hindu Population Growth in Bangladesh: A Demographic Puzzle". Journal of Religion and Demography. 6 (1): 123–148. doi:10.1163/2589742X-00601003. ISSN 2589-7411.

- Rummel 1998, p. 877.

- Nasrin 2014, pp. 67-90.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld - World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Bangladesh : Adivasis". Refworld.

- "Latest News @". Newkerala.com. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh". State.gov. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh - Population Census 1991". catalog.ihsn.org.

- "Bangladesh". United States Department of State. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "Official Census Results 2011 page xiii" (PDF). Bangladesh Government. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2015.

- "Bangladesh: Wave of violent attacks against Hindu minority". Amnesty International. 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- Lintner, Bertil (1 April 2015), Great Game East: India, China, and the Struggle for Asia's Most Volatile Frontier, Yale University Press, pp. 152–154, ISBN 978-0-300-21332-4

- D'Costa, Bina (2011), Nationbuilding, Gender and War Crimes in South Asia, Routledge, pp. 100–, ISBN 978-0-415-56566-0

- "Door out of Dhaka Rema Nagarajan". Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Moinuddin Haider, M.; Rahman, Mizanur; Kamal, Nahid (6 May 2019). "Hindu Population Growth in Bangladesh: A Demographic Puzzle". Journal of Religion and Demography. 6 (1): 123–148. doi:10.1163/2589742X-00601003.

- Streatfield, Peter Kim; Karar, Zunaid Ahsan (2008). "Population Challenges for Bangladesh in the Coming Decades". Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 26 (3): 261–272. PMC 2740702. PMID 18831223.

- বাংলাদেশ পরিসংখ্যান ব্যুরো-গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশ সরকার. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 16 November 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "There may be no Hindus left in Bangladesh in 30 years". The Sunday Guardian Live. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "'No Hindus will be left after 30 years'". Dhaka Tribune. 20 November 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "Bangladeshis Say Amit Shah Playing Jinnah's Game". NewsClick. 8 October 2019. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- NW, 1615 L. St; Washington, Suite 800; Inquiries, DC 20036 USA202-419-4300 | Main202-419-4349 | Fax202-419-4372 | Media (2 April 2015). "Projected Changes in the Global Hindu Population". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- NW, 1615 L. St; Washington, Suite 800; Inquiries, DC 20036 USA202-419-4300 | Main202-419-4349 | Fax202-419-4372 | Media (2 April 2015). "Projected Changes in the Global Hindu Population". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "Demographics of Muslims and Non-Muslims in Bangladesh". Researchgate Publications. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Kalra, Samir (16 January 2015). "Diminishing Hindu Population in Bangladesh From the Perspective of Ethnic Cleansing: A Conscious Unawareness?". Hindu American Foundation. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- N.B. "Bangladesh: 49 million Hindus missing since 1947". Stellar House Publishing. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- Ahmed and Chowdhury 2005, pp. 12-343

- "Bangladesh: Family code". Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- IANS (16 August 2017). "Hindus can practice polygamy in Bangladesh; forbidden to divorce, remarry". Business Standard. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- "बांग्लादेश में ¨हदू परिवारों के हमलावरों पर हो कार्रवाई : सुशील". Dainik Jagran.

- বাংলাদেশ আওয়ামী লীগ এর গঠনতন্ত্র [Constitution of Bangladesh Awami League] (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- "World: Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal". Time. 2 August 1971. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Home - South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre (SAHRDC)". Hrdc.net. Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh Parliament Votes To Make Islam State Religion". New York Times. 8 June 1988. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Primary Report". Hrcbm.org. 31 October 1990. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "South Asia: Afghanistan" (PDF). United States House Committee on International Relations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2006.

- "The truth about Bangladesh's Hindus". Ia.rediff.com. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Analysis: Fears of Bangladeshi Hindus". BBC News. 19 October 2001. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh". State.gov. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "India state warns of Bangladesh refugees". BBC News. 15 November 2001. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh Hindu atrocities 'documented'". BBC News. 8 November 2001. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh scribe arrest 'illegal'". BBC News. 12 January 2002. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Security fears for Hindu festival". BBC News. 8 October 2002. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh slammed for persecution of Hindus". Rediff.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Original USCIRF Report, United States Commission on International Religious Freedom" (PDF). Uscirf.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Bangladesh: Wave of violent attacks against Hindu minority". Press releases. Amnesty International. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- "BJHM: 107 Hindus killed, 31 forcibly disappeared in 2017". Dhaka Tribune. 6 January 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Hindu houses under 'arson' attack ahead of Bangladesh elections". The Statesman. 28 December 2018. Archived from the original on 20 April 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Hindu idols vandalized in Brahmanbaria". Dhaka Tribune. 8 April 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Hindu idols desecrated in Madaripur". Dhaka Tribune. 26 April 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Home - Noakhali Noakhali". Noakhalinoakhali.webs.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Hindu areas in Ctg still out of listing". The Daily Star. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "Hasina axes heavyweights". The Daily Star. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "47-strong council of ministers announced". Dhaka Tribune. 6 January 2019.

- সংখ্যালঘু প্রার্থীদের মধ্যে জয়ী ১৮ জন. Prothom Alo (in Bengali). Retrieved 30 October 2019.

External links

- CIA World Factbook: Bangladesh

- United States Commission on International religious freedom

- Bangladesh Hindus 'will not go back'

- ‘It is a war against the Hindus in Bangladesh’

- HAF Report Summary on Bangladeshi Hindus

- Amnesty International

- Human Rights Congress for Bangladeshi Minorities

- Genocide in East Pakistan

- Police hunt stolen Vishnu statues