Historical background of the Russo-Ukrainian War

A variety of social, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic factors contributed to the sparking of unrest in eastern and southern Ukraine, and the subsequent eruption of the Russo-Ukrainian War, in the aftermath of the early 2014 Ukrainian revolution. Following Ukrainian independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, resurfacing historical and cultural divisions and a weak state structure hampered the development of a unified Ukrainian national identity.[1] In eastern and southern Ukraine, Russification and ethnic Russian settlement during centuries of Russian rule caused the Russian language to attain primacy, even amongst ethnic Ukrainians. In Crimea, ethnic Russians have comprised the majority of the population since the deportation of the indigenous Crimean Tatars by Soviet Union leader Joseph Stalin following the Second World War. This contrasts with western and central Ukraine, which were historically ruled by a variety of powers, such as the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Austrian Empire.[2] In these areas, the Ukrainian ethnic, national, and linguistic identity remained intact.

| Russo-Ukrainian War |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

| Related topics |

The tensions between these two competing historical and cultural traditions erupted into political and social conflict during the Ukrainian crisis, which began when then Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych refused to sign an association agreement with the European Union on 21 November 2013.[3] Support for closer ties with Europe was strong in western and central Ukraine, whilst many in eastern and southern Ukraine traditionally favoured stronger relations with Russia. President Yanukovych, who drew most of his support from eastern regions, was forced out of office in February 2014. His ouster was followed by protests in eastern and southern Ukraine that placed a strong emphasis on the importance of historical ties to Russia, the Russian language, and antipathy towards the Euromaidan movement.[4]

Crimea

After the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, the Crimean Khanate, a vassal of the Ottoman Empire, formed in 1441, was made nominally independent by the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774.[5] It was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1783 as the "Taurida Governorate".[6] The demographics of Crimea underwent dramatic changes in the centuries following the annexation. Prior to its incorporation into Russia, Crimea had been inhabited primarily by the Crimean Tatars, a Turkic people who were predominately Muslim. Furthermore, the peninsula was also populated by Pontic Greeks (Urums) and Armenians, who were mostly Christian. In the run up to the annexation and immediately after it, Russia encouraged, and later ordered, the removal of all Christians from Crimea, and resettled them on the northern shore of the Azov Sea, between Mariupol and Nakhichevan-on-Don.[7][8] Empress Catherine the Great gave many of the lands that had been annexed to her advisors and friends. Native inhabitants of these lands were frequently forced out, spawning a large exodus of Tatars to Ottoman-controlled Anatolia.[9] Russian settlers were brought in to colonise the lands that were once occupied by the fleeing Tatars. By 1903, 39.7% of the population of Crimea, excluding the cities Sevastopol and Yeni-Kale, were members of the Russian Orthodox religion.[10] 44.6% were Muslim.[10] In context of this survey, the identifier "Muslim" is synonymous with ethnic Crimean Tatars. Russians constituted the majority of the population in the two excluded and separately-administered cities.[10] During and directly prior to this time, Crimea became considered the "heart of Russian Romanticism".[11] It was popular with Russians on holiday because of its warm climate and seaside. This association continued into the Soviet period.[11]

Soviet period

Crimea had autonomy within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (SFSR) as the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) from 1921 until 1944. According to the Soviet Census of 1926, 42.2% of the population of the Crimean ASSR was ethnic Russian, 25% was Crimean Tatar, 10.8% was ethnic Ukrainian, 7% was Jewish, and 15% was from other ethnic groups.[12] Soviet leader Joseph Stalin deported the entire population of Crimean Tatars from Crimea and abolished Crimean autonomy in 1944.[13][14] At that time, the Crimean Tatars made up about one-fifth of the population of Crimea, and numbered about 183,155 people.[15] Most were sent to the deserts of Soviet-controlled Central Asia.[14] Around 45% of the deportees died during the deportation process.[16] Crimea was made the "Crimean Oblast" of the Russian SFSR. Following these events, for the first time in history, ethnic Russians comprised the majority of the population of Crimea.

Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev transferred Crimea from the Russian SFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954. This event passed with little fanfare, and was viewed as an insignificant "symbolic gesture", as both republics were a part of the Soviet Union and answerable to the government in Moscow.[17][18][19] Crimean autonomy was re-established in 1991 after a referendum, just prior to dissolution of the Soviet Union.[20]

Ukrainian period

Ukrainian independence was confirmed by a referendum held on 1 December 1991.[21][22] In this referendum, 54% of Crimean voters supported independence from the Soviet Union.[23] This was followed by a 1992 vote by the Crimean parliament to hold a referendum on independence from Ukraine, which spawned a two-year crisis over the status of Crimea.[21] At the same time, the Supreme Soviet of Russia voted to void the cession of Crimea to Ukraine. In June of the same year, the Ukrainian government in Kyiv voted to give Crimea a large amount autonomy as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea within Ukraine. Despite this, fighting between the Crimean government, Russian government, and Ukrainian government continued. In 1994, Russian nationalist Yuri Meshkov won the 1994 Crimean presidential election, and implemented the earlier approved referendum on the status of Crimea.[24][25] 1.3 million people voted in this referendum, 78.4% of whom supported greater autonomy from Ukraine, whilst 82.8% supported allowing dual Russian-Ukrainian citizenship.[26] Later in that same year, the status of Crimea as part of Ukraine was recognised by Russia, which pledged to uphold the territorial integrity of Ukraine in the Budapest Memorandum. This treaty was also signed by the United States, United Kingdom, and France.[27][28] Ukraine revoked the Constitution of Crimea and abolished the office of President of Crimea in 1995.[29] Crimea was granted a new constitution in 1998, which granted lesser autonomy than the previous one.[20][30] Crimean officials would later seek to restore the powers of the previous constitution.[30] Throughout the 1990s, many Crimean Tatar deportees and their descendants returned to Crimea.[31]

One of the main tensions between Russia and Ukraine in the aftermath of the dissolution of the Soviet Union was the status of the Black Sea Fleet, which was and is based in Sevastopol.[27] Under the 1997 Russo-Ukrainian Partition Treaty, which determined the ownership of military bases and vessels in Crimea, Russia was allowed to have up to 25,000 troops, 24 artillery systems (with a calibre smaller than 100 mm), 132 armoured vehicles, and 22 military aeroplanes in Crimea. This treaty was extended in 2010 by Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych. Under this new agreement, Russia was granted rights to garrison the Black Sea Fleet in Crimea until 2042.[32] Residents of the Crimean city of Feodosia protested against the docking of the US Navy ship "Advantage" in June 2006.[33] The protesters carried signs with anti-NATO slogans, and considered the presence of NATO-affiliated troops an "intrusion". Some commentators in Ukraine viewed the protests as being driven by a "Russian hand".[33]

In the 2010 elections to the Crimean parliament, the Party of Regions received the largest share of votes, whilst the second-placed Communist Party of Ukraine received a much smaller share.[34] Both of these political parties would later be targets of the Euromaidan movement.[35][36][37] Former president of Crimea Yuriy Olexandrovich Meshkov called for a referendum on restoring the 1992 Constitution of Crimea in July 2011. As a consequence of this, a local court in Crimea deported Meshkov from Ukraine for five years.[38]

Contemporary demographics

According to the Ukrainian Census of 2001, ethnic Russians comprised 58.5% of the population of the Crimea.[39] The two next largest ethnic groups were Ukrainians, who comprised 24% of the population, and Crimean Tatars, who comprised 10.2%. Other minority ethnic groups recorded as present in Crimea include Belarusians and Armenians. 77% of the population of Crimea reported their native language as Russian, 11.4% indicated Crimean Tatar, and 10.1% indicated Ukrainian.[40]

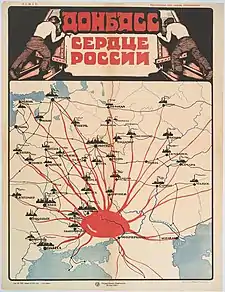

Donbass

Donbass (Ukrainian: Донбас; Russian: Донба́сс), or the Donets Basin, is a region that is today composed of the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine.[41][42] Previously known for being "Wild Fields" (Ukrainian: дике поле, dyke pole), the area that is now called the Donbass was largely under control of the Ukrainian Cossack Hetmanate and the Turkic Crimean Khanate until the mid-late 18th century, when the Russian Empire conquered the Hetmanate and annexed the Khanate.[43] It named the conquered territories "New Russia" (Russian: Новоро́ссия, Novorossiya). As the Industrial Revolution took hold across Europe, the vast coal resources of the Donbass began to be exploited in the mid-late 19th century. This led to a population boom in the region, largely driven by Russian settlers.[44] In 1858, the population of the region was 700,767. By 1897, it had reached 1,453,109. According to the Russian Imperial Census of 1897, ethnic Ukrainians comprised 52.4% of the population of region, whilst ethnic Russians comprised 28.7%.[45] Ethnic Greeks, Germans, Jews and Tatars also had a significant presence in the Donbass, particularly in the district of Mariupol, where they comprised 36.7% of the population.[46] Despite this, Russians constituted the majority of the industrial work-force. Ukrainians dominated rural areas, but cities were often inhabited solely by Russians who had come seeking work in the region's heavy industries.[47] Those ethnic Ukrainians who did move to the cities for work were quickly assimilated into the Russian-speaking worker class.[48]

Soviet period

Along with other territories inhabited by Ukrainians, the Donbass was incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the aftermath of the 1917–22 Russian Civil War. Ukrainians in the Donbass were greatly affected by the 1932–33 Holodomor famine and the Russification policy of Joseph Stalin. As most ethnic Ukrainians were rural peasant farmers (called "kulaks" by the Soviet regime), they bore the brunt of the famine.[49][50] According to the Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain, the population of the area that is now Luhansk Oblast declined by 25% as a result of the famine, whereas it declined by 15–20% in the area that is now Donetsk Oblast.[51] According to one estimate, 81.3% of those who died during the famine in the Ukrainian SSR were ethnic Ukrainians, whilst only 4.5% were ethnic Russians.[52] During the reconstruction of the Donbass after the Second World War, large amounts of Russian workers arrived to repopulate the region, further altering the population balance. In 1926, 639,000 ethnic Russians resided in the Donbass.[53] By 1959, the ethnic Russian population had more than doubled to 2.55 million. Russification was further advanced by the 1958–59 Soviet educational reforms, which led to the nigh elimination of all Ukrainian language schooling in the Donbass.[54][55] By the time of the Soviet Census of 1989, 45% of the population of the Donbass reported their ethnicity as Russian.[56]

Ukrainian period

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, residents of the Donbass were generally in favour of stronger ties with Russia, in contrast to the rest of Ukraine. A 1993 strike by miners in the region called for a federal Ukraine and economic autonomy for Donbass.[56] This was followed by a 1994 consultative referendum on various constitutional questions in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, held concurrently with the first parliamentary elections in independent Ukraine.[57] These questions included whether Russian should be enshrined as an official language of Ukraine, whether Russian should be the language of administration in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, whether Ukraine should federalise, and whether Ukraine should have closer ties with the Commonwealth of Independent States.[58] Close to 90% of voters voted in favour of these propositions.[59] None of them were adopted: Ukraine remained a unitary state, Ukrainian was retained as the sole official language, and the Donbass gained no autonomy.[56]

Donbass voters and politicians had wide influence over Ukrainian politics until the 2004 Orange Revolution.[60] Then Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, who was the target of that revolution, is from the Donbass, and also found most of his support there. At the revolution's height, pro-Yanukovych regional politicians in the Donbass called for a referendum on the establishment of a "South-East Ukrainian Autonomous Republic", or for secession from Ukraine.[60][61][62][63] This did not happen, and Yanukovych's Party of Regions went on to win the 2006 Ukrainian parliamentary election. He was later elected president in 2010. His government, led by Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, implemented a controversial regional language law in 2012. This law granted a language the status of "regional language" where the percentage of representatives of its ethnic group exceeded 10% of the total population of a defined administrative district.[64] Regional language status allowed use of minority languages in courts, schools and other government institutions in these areas of Ukraine. This meant that the Russian language received recognition in the Donbass for the first time since Ukrainian independence.[64]

Contemporary demographics

According to the Ukrainian Census of 2001, 57.2% of the population of the Donbass was ethnic Ukrainian, 38.5% was ethnic Russian, and 4.3% belonged to other ethnic groups, mainly Greeks (1.1%) and Belarusians (0.9%).[65] 72.8% of the population reported that their native language was Russian, whilst 26.1% reported that it was Ukrainian.[66] Other languages, spoken mainly by minority ethnic groups, accounted for 1.1% of the population. Amongst these groups, only the Roma were reported as not using Russian in daily life, citing Romani instead.[66]

Kharkiv Oblast

Previously a sparsely populated region, large amounts of ethnic Ukrainian settlers first came to the land that is now Kharkiv Oblast around the time of the 1648–57 Khmelnytsky uprising. These settlers had fled fighting between Ukrainian Cossacks and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth near the Dnieper River. The area that they settled in was named "Sloboda Ukraine" (Ukrainian: Слобiдська Україна, Slobodskaya Ukraina).[67] Over the following centuries, multiple waves of immigration to Sloboda Ukraine brought both ethnic Ukrainians and ethnic Russians. Prior to the 19th century, only smalls amounts of Russians settled in the area. They tended to live in cities, whilst rural areas were dominated by ethnic Ukrainians. The region had an autonomous Cossack government until it was abolished by Catherine the Great in 1765.[68] By 1832, the urban-rural divide became firmly entrenched: 50% of merchants were ethnic Russians, as were 45% of factory owners.[67] In line with this increasing Russification, the name Sloboda Ukraine was replaced by Kharkov Governorate in 1835. Ethnic Russians in agriculture-dominated Kharkiv were never as numerous as in the industrial Donbass, and the region always retained a distinct Ukrainian culture.[67] This is illustrated by the Imperial Census of 1897, which recorded the native language of 80.6% of the population of Kharkov Governorate as Ukrainian, whereas Russian was recorded as the native language of only 17.7% of the population.[69]

The city of Kharkiv became the capital of the Ukrainian SSR in 1922. During the 1932–33 Holodomor famine, the ethnic Ukrainian-populated countryside of Kharkiv Oblast was devastated.[70] At the same time, the city of Kharkiv became heavily industrialised, and its ethnic Russian population boomed. By the time of the Soviet Census of 1989, 33.2% of the population of Kharkiv Oblast identified as ethnic Russian, and 48.1% of the population reported that their native language was Russian.[71][72]

Contemporary demographics

According to the Ukrainian Census of 2001, ethnic Ukrainians comprised 70.7% of the population of Kharkiv Oblast, whilst ethnic Russians comprised 25.6%.[73] Other minority ethnic groups recorded as present in Kharkiv Oblast include Armenians, Jews, and Belarusians. 53.8% of the population reported that their native language was Ukrainian, whilst 44.3% reported that it was Russian.[72]

Odessa Oblast

In 1593, the Ottoman Empire conquered the area that is now Odessa Oblast, and incorporated it as the Özü Eyalet, unofficially known as the Khan Ukraine.[74] In the aftermath of the Russo-Turkish War of 1787–92, Yedisan, roughly corresponding to the modern city of Odessa, was recognised by the Ottoman Empire in the Treaty of Jassy as being a part of the Russian Empire.[75] According to the first Russian Empire census of the Yedisan region, conducted in 1793 after the expulsion of the Nogai Tatars, forty-nine villages out of the sixty-seven between the Dniester River and the Southern Bug River were ethnically Romanian (also called Moldavians).[76] Subsequently, ethnic Russians colonised the area, and established many new cities and ports. In 1819, the city of Odessa became a free port. It was home to a very diverse population, and was frequented by Black Sea traders. In less than a century, the city of Odessa grew from a small fortress to the biggest city in the region of New Russia.[77]

At the time of the Imperial Census of 1897, the population of the approximate area of modern Odessa Oblast was 1,115,949.[78] According to that census, 33.9% of the population was ethnic Ukrainian, 26.7% was ethnic Russian, 16.1% was ethnic Jewish, 9.2% was ethnic Moldavian, 8.6% was ethnic German, 2% was ethnic Polish, and 1.6% was ethnic Bulgarian. These numbers show that there was a high level of ethnic diversity in the region, and that no group had an outright majority.[78]

In the early period of the Ukrainian SSR, Odessa Governorate was formed out of parts of the former Kherson Governorate.[79] This new area formed the basis for modern Odessa Oblast. Throughout the interwar period, Budjak was part of the Kingdom of Romania. The 1932–33 Holodomor famine had a profound demographic effect on the region.[80] Its population declined by 15–20%.[51] About a decade later, the Nazi occupation of Ukraine during the Second World War had a devastating impact on the region's previously large Jewish population.[81] Also during the war, the ethnically-diverse Budjak was annexed to the Ukrainian SSR as Izmail Oblast. It was merged into Odessa Oblast in 1954.

By the time of the Soviet Census of 1989, 27.4% of the population of Odessa Oblast identified themselves as ethnic Russian, whilst 55.2% identified themselves as ethnic Ukrainians.[82][83] The remainder was made up mostly of Moldavians, Bulgarians and Gagauz.

Contemporary demographics

According to the Ukrainian Census of 2001, ethnic Ukrainians comprised 62.8% of the population of Odessa Oblast, whilst ethnic Russians comprised 20.7%.[83] Significant Bulgarian and Moldavian communities are present, centred on the historical region of Budjak. These comprised 6.1% and 5% of the population of Odessa Oblast respectively. 46.3% of the population reported that their native language was Ukrainian, whilst 41.9% reported that it was Russian.[84] 11.8% specified other languages, mainly Bulgarian and Moldavian.

References

- "What you should know about the Ukraine crisis". PBS Newshour. 7 March 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "History and Geography Help Explain Ukraine Crisis". National Geographic. 24 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- "A Ukraine City Spins Beyond the Government's Reach". The New York Times. 15 February 2014.

- Richard Sakwa (2014). Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands. I.B.Tauris. p. 155. ISBN 978-0857738042.

- Keating, Joshua (6 March 2014). "Turkey's Black Sea Blues". Slate. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- "Sorry, Turkey: You're Not Getting Crimea Back". Foreign Policy. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Alan W. Fisher (1978). The Crimean Tatars: Studies of Nationalities in the USSR. Hoover Press. pp. 62–67. ISBN 0817966633.

- Shafiyev, Farid (2018). Resettling the borderlands : state relocations and ethnic conflict in the South Caucasus. Montreal. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7735-5372-9. OCLC 1027218713.

- "POPULATION TRANSFER: The Crimean Tatars Return Home". Cultural Society. 5 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- Hakan Kırımlı (1996). National movements and national identity among the Crimean Tatars: (1905-1916). BRILL. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9004105093.

- Judah, Ben (2 March 2014). "Why Russia No Longer Fears the West". Politico. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. p. 207. ISBN 0-7656-0665-8.

- "Why Crimea is so dangerous". BBC. 11 March 2014.

- Flintoff, Corey (23 November 2013). "Once Victims of Stalin, Ukraine's Tatars Reassert Themselves". NPR. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- "Постанова про депортацію татар і перетворення Криму на область. ДОКУМЕНТИ". Ukrainskya Pravda. 17 May 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- "Crimean Tatars". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Calamur, Krishnadev (27 February 2014). "Crimea: A Gift To Ukraine Becomes A Political Flash Point". NPR. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Keating, Joshua (25 February 2014). "Kruschev's Gift". Slate. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Krim-Übertragung : War der Dnjepr-Kanal der Grund? – Nachrichten Geschichte". DIE WELT.

- Sasse, Gwendolyn (3 March 2014). "Crimean autonomy: A viable alternative to war?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- Schmemann, Serge (6 May 1992). "Crimea Parliament Votes to Back Independence From Ukraine". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Schmemann, Serge (22 May 1992). "Russia Votes to Void Cession of Crimea to Ukraine". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Don Harrison Doyle, ed. (2010). Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements. University of Georgia Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-0820330082.

- "Separatist Winning Crimea Presidency". The New York Times. 31 January 1994. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Bohlen, Celestine (23 March 1994). "Russia vs. Ukraine: A Case of the Crimean Jitters". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Chronology for Crimean Tatars in Ukraine". Minorities at Risk Project. University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Zaborsky, Victor (September 1995). "Crimea and the Black Sea Fleet in Russian-Ukrainian Relations".

- "What is so dangerous about Crimea?". BBC. 27 February 2014.

- "Ukraine Moves To Oust Leader of Separatists". The New York Times. 19 March 1995. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Crimea wants to equate its Constitution with Ukraine's Basic Law". Ukrinform. 18 July 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- "The Crimean Tatars: A Primer". The New Republic. 2 March 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Deal Struck on Gas, Black Sea Fleet, The Moscow Times (21 April 2010)

- "Ukraine: U.S. Navy Stopover Sparks Anti-NATO Protests". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 1 June 2006. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- "Regions Party gets 80 of 100 seats on Crimean parliament". Interfax Ukraine. 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014.

- "Thousands mourn Ukraine protester amid unrest". Al Jazeera. January 2014.

- "У Сумах розгромили офіс ПР". UA: The Insider.

- "В Киеве разгромили офис ЦК КПУ" [In Kyiv, Communist Party Central Committee Office was destroyed]. Gazeta. UA. 22 February 2014. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ЕКС-ПРЕЗИДЕНТА КРИМУ ВИСЛАЛИ З УКРАЇНИ [Ex-President of Crimea sent FROM UKRAINE]. Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 13 July 2011.

- "National composition of the population in Autonomous Republic of Crimea". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

"National composition of the population in Sevastopol". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014. - "Linguistic composition of Autonomous Republic of Crimea". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

"Linguistic composition of Sevastopol". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014. - Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0521526086.

- "Donetsk might agree with some points of Ukraine's law on special status of Donbass". Informational Telegraph Agency of Russia. 16 September 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 0521526086.

- Andrew Wilson (April 1995). "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (2): 274. JSTOR 261051.

- Hiroaki Kuromiya (2003). Freedom and Terror in the Donbas: A Ukrainian-Russian Borderland, 1870s–1990s. Cambridge University Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0521526086.

- "The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 − Breakdown of population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia". Institute of Demography at the National Research University 'Higher School of Economics'. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Lewis H. Siegelbaum; Daniel J. Walkowitz (1995). Workers of the Donbass Speak: Survival and Identity in the New Ukraine, 1982–1992. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-7914-2485-5.

- Rapawy, Stephen (1997). Ethnic Reidentification in Ukraine (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Census Bureau, International Programs Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Potocki, Robert (2003). Polityka państwa polskiego wobec zagadnienia ukraińskiego w latach 1930–1939 (in Polish and English). Lublin: Instytut Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej. ISBN 978-8-391-76154-0.

- Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. pp. 208–209. ISBN 0-7656-0665-8.

- "The Number of Dead". Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Sergei Maksudov, "Losses Suffered by the Population of the USSR 1918–1958", in The Samizdat Register II, ed. R. Medvedev (London–New York 1981)

- Andrew Wilson (April 1995). "The Donbas between Ukraine and Russia: The Use of History in Political Disputes". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (2): 275. JSTOR 261051.

- L.A. Grenoble (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 1402012985.

- Bohdan Krawchenko (1985). Social change and national consciousness in twentieth-century Ukraine. Macmillan. ISBN 0333361997.

- Don Harrison Doyle, ed. (2010). Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements. University of Georgia Press. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-0820330082.

- Kataryna Wolczuk (2001). The Moulding of Ukraine. Central European University Press. pp. 129–188. ISBN 9789639241251.

- Hryhorii Nemyria (1999). Regional Identity and Interests: The Case of East Ukraine. Between Russia and the West: Foreign and Security Policy of Independent Ukraine. Studies in Contemporary History and Security Policy.

- Bohdan Lupiy. "Ukraine And European Security - International Mechanisms As Non-Military Options For National Security of Ukraine". Individual Democratic Institutions Research Fellowships 1994–1996. North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Don Harrison Doyle, ed. (2010). Secession as an International Phenomenon: From America's Civil War to Contemporary Separatist Movements. University of Georgia Press. pp. 287–288. ISBN 978-0820330082.

- David Crouch (28 November 2004). "East Ukraine threatens autonomy". The Guardian. Donetsk. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- "Ukrainian region seeks autonomy". BBC News. 28 November 2004. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- Ingmar Bredies, ed. (2007). Aspects of the Orange Revolution IV: Foreign Assistance and Civic Action in the 2004 Ukrainian Presidential Elections. Columbia University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-3898218085.

- "Ukrainians protest against Russian language law". The Guardian. 4 July 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- "National composition of population in Donetsk Oblast". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

"National composition of population in Luhansk Oblast". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014. - "Linguistic composition of Donetsk Oblast". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

"Linguistic composition of Luhansk Oblast". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014. - Susan Stuart (2005). Explaining the Low Intensity of Ethnopolitical Conflict in Ukraine. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 76–78. ISBN 3825883310.

- "THE AUTONOMOUS HETMAN STATE AND SLOBODA UKRAINE". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- "Breakdown of the population of Kharkov Governorate by mother tongue". First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- Blair A. Ruble (2008). Establishing a New Right to the Ukrainian City. Woodrow Wilson Center. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1933549453.

- Neil Melvin (1995). Russians Beyond Russia. A&C Black. p. 87. ISBN 1855672332.

- "Linguistic composition of Kharkiv Oblast". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- "National composition of the population in Kharkiv Oblast". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Secrieru, Mihaela (ed.). "Republic of Moldavia – an Intermezzo on the Signing and the Ratification of the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages" (PDF). Iași: University of Iaşi (Alexandru Ioan Cuza). p. 2.

On the left shore of the River Nistru [Dniester] there was the Khanate of Ukraine and of the properties of the Polish Crown, and their inhabitants, until the end of the 18th century, were the Moldavians.

- Esposito, John L., ed. (1999). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. pp. 392, 698. ISBN 0-19-510799-3.

- E. Lozovan, Romanii orientali, "Neamul Romanesc", 1/1991, p.32.

- Patricia Herlihy (1973). "Odessa: Staple Trade and Urbanization in New Russia". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. Neue Folge, Bd. 21.

- "The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 − Breakdown of population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia". Institute of Demography at the National Research University 'Higher School of Economics'. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

"The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 − Breakdown of population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia". Institute of Demography at the National Research University 'Higher School of Economics'. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

"The First General Census of the Russian Empire of 1897 − Breakdown of population by mother tongue and districts in 50 Governorates of the European Russia". Institute of Demography at the National Research University 'Higher School of Economics'. Retrieved 22 September 2014. - Serhy Yekelchyk, Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3

- Голод 1932–1933 років на Україні: очима істориків, мовою документів. Колективізація і голод на Україні: 1929-1933. Збірник матеріалів і документів - 1933 [The famine of 1932-1933 in Ukraine: through the eyes of historians and the language of documents. Collectivization and famine in Ukraine: 1929-1933. Collection of materials and documents - 1933] (in Ukrainian). Archives.gov.ua. 1990. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- "Odessa". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Martin W. Lewis (24 March 2014). "Russian Envelopment? Ukraine's Geopolitical Complexities". GeoCurrents.info. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "National composition of the population in Odessa Oblast". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- "The Oxford History of Islam". Ukrainian Census of 2001. State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. Retrieved 21 September 2014.