Kigali

Kigali (Kinyarwanda: [ci.ɡɑ́.ɾi]) is the capital and largest city of Rwanda. It is near the nation's geographic centre in a region of rolling hills, with a series of valleys and ridges joined by steep slopes. The city has been Rwanda's economic, cultural, and transport hub since it became the capital following independence from Belgian rule in 1962.

Kigali | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top: Kigali skyline, Remera suburb and Amahoro stadium, Street scene in Kigali CBD, Sainte-Famille Church | |

Kigali Map of Rwanda showing the location of Kigali  Kigali Kigali (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 1°56′38″S 30°3′34″E | |

| Country | Rwanda |

| Province | Kigali Province |

| Founded | 1907 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Pudence Rubingisa |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 730 km2 (280 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,567 m (5,141 ft) |

| Population (2012 census) | |

| • Capital city | 1,132,686 |

| • Density | 1,552/km2 (4,020/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 859,332 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (CAT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (none) |

| Districts[1] 1. Gasabo 2. Kicukiro 3. Nyarugenge |  |

| HDI (2018) | 0.632[2] medium · 1st of 5 |

| Website | www |

In an area controlled by the Kingdom of Rwanda from the 17th century and then by the German Empire, the city was founded in 1907 when Richard Kandt, the colonial resident, chose the site for his headquarters, citing its central location, views and security. Foreign merchants began to trade in the city during the German era, and Kandt opened some government-run schools for Tutsi Rwandan students. Belgium took control of Rwanda and Burundi during World War I, forming the mandate of Ruanda-Urundi. Kigali remained the seat of colonial administration for Rwanda but Ruanda-Urundi's capital was at Usumbura (now Bujumbura) in Burundi and Kigali remained a small city with a population of just 6,000 at the time of independence.

Kigali grew slowly during the following decades. It was not initially directly affected by the Rwandan Civil War between government forces and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), which began in 1990. However, in April 1994 Rwanda's president was killed when his aircraft was shot down near Kigali. Social tensions erupted in the genocide that followed, with Hutu extremists loyal to the interim government killing an estimated 500,000–800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu nationwide. The RPF resumed fighting, ending a cease-fire of more than a year. They gradually took control of most of the country and seized Kigali on 4 July 1994. Post-genocide Kigali has experienced rapid population growth, with much of the city rebuilt.

The city of Kigali is one of the five provinces of Rwanda, with boundaries set in 2006. It is divided into three districts—Gasabo, Kicukiro, and Nyarugenge—which historically had control of significant areas of local governance. Reforms in January 2020 transferred much of the districts' power to the city-wide council. The city also hosts the main residence and offices of the President of Rwanda and most government ministries. The largest contributor to Kigali's gross domestic product is the service sector, but a significant proportion of the population works in agriculture including small-scale subsistence farming. Attracting international visitors is a priority for city authorities, including leisure tourism, conferences and exhibitions.

History

Pre-colonial period

The earliest inhabitants of what is now Rwanda were the Twa, a group of aboriginal pygmy hunter-gatherers who settled the area between 8000 and 3000 BC and remain in the country today.[3][4] They were followed between 700 BC and AD 1500 by a number of Bantu groups, including the Hutu and Tutsi, who began clearing forests for agriculture.[4][5] According to oral history, the Kingdom of Rwanda was founded in the 14th century on the shores of Lake Muhazi, around 40 kilometres (25 mi) east of modern Kigali.[6][7][8][9] The early kingdom included Kigali but it was a small state at this point in its history with larger and more powerful neighbours, Bugesera and Gisaka.[10][11] A member of the Gisaka dynasty killed Rwanda's king Ruganzu Bwimba in the 16th century, but Ruganzu's son Cyirima Rugwe fought back with help from Bugesera and was able to expand Rwanda's territory.[12] In the late 16th or early 17th century, the kingdom of Rwanda was invaded from the north by the Banyoro of modern-day Uganda.[12] The king was forced to flee westward, leaving Kigali and eastern Rwanda in the hands of Bugesera and Gisaka.[7][11] The formation of a new Rwandan dynasty in the 17th century by the mwami (king), Ruganzu Ndori, followed by eastward invasions and the conquest of Bugesera, marked the beginning of the Rwandan kingdom's dominance in the area.[13] The capital of the kingdom was at Nyanza, in the south of the country.[14]

Colonial period

.jpg.webp)

The founding of Kigali is generally dated to 1907, when German administrator and explorer Richard Kandt was appointed as the first resident of Rwanda, and established the city as the headquarters.[15][16][17] Rwandan scholar Alexis Kagame, who wrote extensively on the country's oral history and traditions from the 1940s until his death in 1981, promoted an alternative theory that the city was established as a capital under Cyilima I Rugwe in either the 1300s or the 1500s. There is little direct evidence for this, however, and the more recent kings of the pre-colonial era are known to have been based at Nyanza.[17] Rwanda and neighbouring Burundi had been assigned to Germany by the Berlin Conference of 1884,[18] forming part of German East Africa, and Germany established a presence in the country in 1897 with the formation of an alliance with the king, Yuhi V Musinga.[19] Kandt arrived in 1899, to explore Lake Kivu and search for the source of the Nile.[20]

When Germany decided in 1907 to separate the administration of Rwanda from that of Burundi, Kandt was appointed as resident.[21] He chose to make his headquarters in Kigali due to its central location in the country,[22] and also because the site on Nyarugenge Hill afforded good views and security.[22] Kandt's house, located close to the central business district (CBD), was the first European-style house in the city,[23] and remains in use today as the Kandt House Museum of Natural History.[24] Despite a German ordinance written in 1905, which prohibited "non-indigenous natives" from entering Rwanda,[25] Kandt began permitting the entry of foreign traders in 1908, which allowed commercial activity to begin in Rwanda.[26][25] Kigali's first businesses were established by Greek and Indian merchants,[26] with assistance from Baganda and Swahili people.[27] Items traded included cloth and beads.[27] Commercial activity was limited and there were only around 30 firms in the city by 1914.[28] Kandt also opened government-run schools in Kigali, which began educating Tutsi students.[29]

Belgian forces took control of Rwanda and Burundi during World War I, with Kigali being captured by the Northern Brigade led by Colonel Philippe Molitor on 6 May 1916.[30] The Belgians were granted sovereignty by a League of Nations mandate in 1922, forming the mandatory territory of Ruanda-Urundi.[31] In early 1917, Belgium attempted to assert direct rule on the mandate, placing King Musinga under arrest and sidelining Rwandans in the judiciary.[32] In this period, Kigali was one of two provincial capitals, alongside Gisenyi.[33] An agricultural-labour shortage caused by the recruitment of locals to assist the European armies during the war, the plundering of food by soldiers, and torrential rains which destroyed crops, led to a severe famine at the start of the Belgian administration.[34] The famine, combined with the difficulty of governing the complex Rwandan society, prompted the Belgians to re-establish the German-style indirect rule at the end of 1917.[35] Musinga was restored to his throne at Nyanza, with Kigali remaining home to the colonial administration.[36][37] This arrangement persisted until the mid-1920s,[38] but from 1924 the Belgians began once more to sideline the monarchy, this time permanently.[39] Belgium took over control of dispute resolution, appointment of officials and collection of taxes.[38][40] Kigali remained relatively small through the remainder of the colonial era, as much of the administration took place in Ruanda-Urundi's capital Usumbura, now known as Bujumbura in Burundi. Usumbura's population exceeded 50,000 during the 1950s and was the mandate's only European-style city,[41] while Kigali's population remained at around 6,000 until independence in 1962.[22]

Post-independence era

Kigali became the capital upon Rwandan independence in 1962.[42][15] Two other cities were considered – Nyanza, as the traditional seat of the mwami, and the southern city of Butare (known as Astrida under the Belgians), due to its prominence as a centre of intellect and religion.[43] The authorities eventually chose Kigali because of its more central location. The city grew steadily during the following decades; in the early 1970s the population was 25,000 with only five paved roads, and by 1991 it was around 250,000.[44] On 5 July 1973 there was a bloodless military coup, in which minister of defence Juvénal Habyarimana overthrew ruling president Grégoire Kayibanda.[45] Military officers had gathered in Kigali for a military tattoo to commemorate Independence Day a few days earlier, and they began occupying government buildings from dawn on 4 July.[46] Businesses closed for a few days, and troops patrolled across the city,[47] but the coup was bloodless and life continued as normal, historian Gérard Prunier describing the reaction as "widespread popular relief".[48] According to a US Department of State diplomatic cable sent shortly afterwards, the disruption following the coup was short-lived and the army had left the streets by 11 July.[49]

Kigali was not directly affected during the first three years of the 1990–1994 Rwandan Civil War, although the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) did come close to attacking the city in February 1993.[50] In December of the same year, following the signing of the Arusha Accords, a United Nations peacekeeping force was established in the city, and the RPF were granted use of a building in the city for their diplomats and soldiers.[51] In April 1994 President Habyarimana was assassinated when his plane was shot down near Kigali International Airport. Burundian president Cyprien Ntaryamira was also killed in the attack.[52] This was the catalyst for the Rwandan genocide, in which 500,000–800,000 Tutsi and politically moderate Hutu were killed in well-planned attacks on the orders of the interim government.[53][54] Opposition politicians based in Kigali were killed on the first day of the genocide,[55] and the city then became the setting for fierce fighting between the army and the RPF including at the latter's base.[56] The RPF began attacking from the north of the country, and gradually took control of most of Rwanda between April and June.[57] After encircling Kigali and cutting off its supply routes,[58] they began fighting for the city itself in mid-June.[59] The government forces had superior manpower and weapons but the RPF fought tactically,[59] and were able to exploit the fact that the government forces were concentrating on the genocide rather than the fight for Kigali.[59] The RPF took control of Kigali on 4 July,[60] a date now commemorated as Liberation Day, a Rwandan national holiday.[61]

Since the war and genocide the city has experienced rapid population growth as a result of migration from other areas, as well as a high birth rate.[62] Buildings that were heavily damaged during the fighting have been demolished, much of the city has been rebuilt, and modern office buildings and infrastructure now exist across the city. A masterplan, adopted by the city and the government in 2013 and supported by international finance and labour, seeks to establish Kigali as a decentralised modern city by 2040.[63] The development has been accompanied by forced eviction of residents in informal housing zones, however, and groups such as Human Rights Watch have accused the government of removing poor people and children from the city's streets and moving them to detention centres.[64][65]

Geography

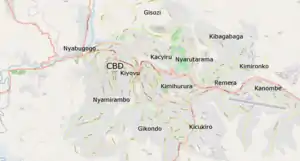

Kigali is located in the centre of Rwanda, at 1°57′S 30°4′E.[66] Like the rest of Rwanda it uses Central Africa Time, and is two hours ahead of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC+02:00) throughout the year.[67] The city is coterminous with the province of Kigali, one of the five provinces of Rwanda introduced in 2006 as part of a restructuring of local government in the country. The city has boundaries with the Northern, Eastern and Southern provinces.[68] It is divided into three administrative districts—Nyarugenge in the south west, Kicukiro in the south east, and Gasabo, which occupies the northern half of the city's territory.[1] The built-up urban area covers about 70% of the municipal boundaries.[69] Kigali lies in a region of rolling hills,[7] with a series of valleys and ridges joined by steep slopes.[70] It is situated between Mount Kigali and Mount Jali,[22] both of which have elevations of more than 1,800 m (5,906 ft) above sea level,[71] while the lowest areas of the city have an altitude of 1,300 m (4,265 ft).[72] Geologically, Kigali is in a granitic and metasedimentary region, with lateritic soils on the hills and alluvial soils in the valleys.[73]

The Nyabarongo River, part of the upper headwaters of the Nile,[74] forms the western and southern borders of the administrative city of Kigali,[75] although this river lies somewhat outside the built-up urban area.[76] The largest river running through the city is the Nyabugogo River, which flows south from Lake Muhazi before flowing west between Mount Kigali and Mount Jali, and draining into the Nyabarongo.[77] The Nyabugogo is fed by various smaller streams throughout the city, and its drainage basin contains most of Kigali's territory,[77] other than areas in the south which outflow directly to the Nyabarongo.[78] The rivers are flanked by wetlands, which act as a water store and flood protection for the city, although these are under threat from agriculture and development.[78]

Cityscape

Kigali's CBD, sometimes known in English by the Kinyarwanda term mu mujyi ("in town"), is on Nyarugenge Hill and was the site of the original city founded by Richard Kandt in 1907.[22] The house that Kandt lived in is now the Kandt House Museum of Natural History.[23] The CBD is situated towards the western edge of the built-up area,[22] as the terrain to the east was more suitable for development of the expanding city than the high slopes of Mount Kigali to the west. Several of Rwanda's tallest buildings, including the twenty-storey Kigali City Tower, are located in the CBD, as are the headquarters of the country's largest banks and businesses.[79] Other buildings in the CBD include the upmarket Serena, Marriott and Mille Collines hotels,[80] the University Teaching Hospital of Kigali,[81] the national university's College of Science and Technology,[82] and government buildings such as the National Bank of Rwanda and the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning.[83][84]

To the south west of the CBD, and also on the Nyarugenge Hill, is the suburb of Nyamirambo.[85] This was the second part of the city to be settled, being built in the 1920s by the Belgian colonial government as a home for civil servants and Swahili traders. The latter group were mostly members of the Islamic faith, which led to Nyamirambo being known as the "Muslim Quarter".[86] Nyamirambo's Green Mosque (Masjid al-Fatah) is the oldest mosque in Kigali, dating to the 1930s. Travel publisher Rough Guides described Nyamirambo in 2015 as "Kigali's coolest neighbourhood", citing its multi-cultural status and an active nightlife, which is not found in much of the rest of the city.[87] North of Nyamirambo, and west of the CBD is Nyabugogo. Situated at the lowest part of the city, in the valley of the eponymous Nyabugogo River, Nyabugogo is home to Kigali's principal bus and share taxi station, with vehicles departing for numerous domestic and international destinations.[88]

The remainder of Kigali's suburbs lie to the east of the CBD, with an urban sprawl spanning the many hills and ridges. Kiyovu is the closest, on the eastern slopes of Nyarugenge Hill. The higher part of Kiyovu, to the south of main road KN3, has been home to wealthy foreign residents and Rwandans since colonial times, with large houses and high-end restaurants.[89] The residence of the Rwandan president is located in this area.[90] The lower part of Kiyovu, north of the main road, consisted until 2008 of informal settlements that had formed after independence, when strict residence rules were relaxed.[89] The houses in lower Kiyovu were expropriated by the government in 2008 with residents compensated or relocated to other areas, including to a purpose-built estate in the Batsinda neighbourhood. The government has plans to create a new business district in lower Kiyovu to complement the existing CBD, although as of late 2017 there had been only a handful of buildings erected there.[91] Other eastern suburbs include Kacyiru, home to most government departments and the office of the president;[92] Gisozi, where the Kigali Genocide Memorial is located;[93] Nyarutarama, an affluent suburb housing the city's only golf course;[94] Kimihurura; Remera and Kanombe, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the CBD on the eastern edge of the city, where Kigali International Airport is located.[95]

Climate

Like the rest of Rwanda, Kigali has a temperate tropical highland climate, with temperatures that are cooler than typical for equatorial countries because of its high elevation.[96] Under the Köppen climate classification, Kigali is in the tropical savanna climate (Aw) zone, straddling the subtropical highland climate.

The city has an average daily temperature range between 15 and 27 °C (59 and 81 °F), with little variation through the year.[97] There are two rainy seasons annually, from February to June and from September to December. These are separated by two dry seasons: the major one from June to September, during which there is often no rain at all, and a shorter and less severe one from December to February.[98] The wettest month is April, with an average rainfall of 154 millimetres (6.1 in), while the driest month is July.[97] Global warming has caused a change in the pattern of the rainy seasons. According to a report by the Strategic Foresight Group, change in climate has reduced the number of rainy days experienced during a year, but has also caused an increase in frequency of torrential rains. Strategic Foresight also characterise Rwanda as a rapidly warming country, with an increase in average temperature of between 0.7 °C to 0.9 °C over the fifty years to 2013.[99]

| Climate data for Kigali, Rwanda | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.9 (80.4) |

27.4 (81.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.6 (60.1) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

16.1 (61.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

15.7 (60.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 76.9 (3.03) |

91.0 (3.58) |

114.2 (4.50) |

154.2 (6.07) |

88.1 (3.47) |

18.6 (0.73) |

11.4 (0.45) |

31.1 (1.22) |

69.6 (2.74) |

105.7 (4.16) |

112.7 (4.44) |

77.4 (3.05) |

950.9 (37.44) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 11 | 11 | 15 | 18 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 17 | 17 | 14 | 133 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization.[97] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

As of the 2012 Rwandan census, the population of Kigali was 1,132,686,[100] of which 859,332 were urban residents.[100] The population density was 1,552 inhabitants per square kilometre (4,020/sq mi).[101] At the time of independence in 1962, Kigali had 6,000 inhabitants, consisting primarily of those associated with the Belgian colonial residency.[102] It grew considerably after being named as the independent nation's capital,[44] although it remained a relatively small city until the 1970s due to government policies restricting rural-to-urban migration.[103] The population reached 115,000 by 1978, and 235,000 by 1991.[103] The city lost a large fraction of its people during the 1994 genocide,[104] including those killed and those who fled to neighbouring countries.[103] From 1995 the economy began to recover and large numbers of long-term Tutsi refugees returned from Uganda.[103] Many of these refugees settled in Kigali and other urban areas, due to difficulty in obtaining land in other parts of the country.[105] This phenomenon, coupled with a high birth rate and increased rural-to-urban migration,[62] meant that Kigali reattained its previous size quite quickly and began to grow even more rapidly than before.[103] The population exceeded 600,000 in 2002, and in the 2012 census had almost doubled to 1.13 million, although this was in part because the administrative boundaries of the city had been expanded.[44]

As of the 2012 census, 51.7 percent of residents were male.[nb 1] The Rwanda Environment Management Authority hypothesised that the high male-to-female ratio was due to a tendency for men to migrate to the city in search of work outside the agricultural sector, while their wives remained in a rural home.[106] The population is young, with 73 percent of residents being less than 30 years old,[106] and 94 percent under the age of 50.[nb 2] The city has a higher proportion of 14–35 year olds than the Rwanda average, with 50.3 per cent versus 39.6 per cent nationwide.[107] Children between birth and 17 years of age have a below-average share of the total, with 39.6 per cent against 47.7 per cent nationally. These differences are attributed by the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR) to the migration of working-age Rwandans from rural to urban areas.[108] Similarly, Kigali has a lower level of over-60s, with 2.6 per cent, than the Rwanda average of 4.9 per cent, also likely reflecting the tendency for non-working-age inhabitants to live rurally.[109] In 2014, the proportion of people classified as living in poverty within Kigali was 15 percent, compared with 37 percent for Rwanda as a whole.[110] The 2012 census recorded a workforce of 487,000 in Kigali.[111] The city's biggest employment sector is agriculture, fishing and forestry, covering 24 per cent of the workforce; utilities and financial services with 21 percent; trade 20 percent and government 12 percent.[111]

In 2018 Kigali scored was 0.632 on the Human Development Index (HDI), a composite measure of life expectancy and health, education, and standard of living.[2][112] This figure had risen or remained the same every year since 1992, during the civil war, when the figure was 0.223. It is also the highest of Rwanda's five provinces with the next highest, the Northern Province, recording an HDI of 0.531.[2] Analysts at the World Bank attribute the gains in HDI seen across Rwanda as a whole to a "strong focus on homegrown policies and initiatives", which have accompanied economic growth.[113]

As with Rwanda as a whole, Christianity is the dominant religion in Kigali. In the 2012 census, 42.1 per cent of the city's inhabitants identified as Protestant with a further 9.1 per cent following Adventism, which was classified separately. Catholics formed 36.8 per cent of the population. Islam is more prevalent in Kigali than elsewhere in Rwanda, with 5.7 per cent of people following the faith compared with 2.0 per cent nationwide. Jehovah's Witnesses form 1.2 per cent and other faiths 0.3 per cent, while those who profess no religion number 3.0 per cent.[114]

Economy

Kigali is the economic and financial hub of Rwanda, serving as the country's main port of entry and largest business centre.[115] The NISR does not maintain detailed economic data for subnational entities in Rwanda, but economists have used various measures to estimate the city's output. A 2015 working paper by the World Bank Policy Research unit used the amount of light visible at night in different regions as a proxy for relative gross domestic product (GDP), and found that the three districts of Kigali represented 42% of Rwanda's total night-light output.[116][117] When translated, this gives a total city GDP of approximately US$1.8 billion or $1,619 per capita,[nb 3] compared with a national average of $436 per capita.[117] Another 2015 World Bank study measured the total turnover of registered companies in the country, as reported to the Rwanda Revenue Authority, and found that 92% of these were from the city of Kigali. However, the authors noted that this figure excluded turnover from small-scale farming, and was also inflated for companies headquartered in Kigali with revenue generated elsewhere in Rwanda.[118] Official statistics classify economic activity as either "farm" or "non-farm", and Kigali accounts for 39% of non-farm waged employees in the country.[116]

.jpg.webp)

The largest contributor to Kigali's economy is the service sector. The World Bank estimates that services contributed 53% of GDP in 2014,[116] while a 2012 study by Surbana International Consultants put the figure at almost 62%.[119] Activity within the service sector includes retail, information technology, transport and hotels, and real estate. The city authorities have prioritised business services for expansion, constructing several modern buildings in the CBD such as the Kigali City Tower. Attracting international visitors is a priority for both the city and the Rwanda Development Board,[119] including leisure tourism, conferences and exhibitions. Kigali is the major arrival point for tourists visiting Rwanda's national parks and tracking mountain gorillas,[120] and has its own sites of interest such as the Kigali Genocide Memorial and ecotourist facilities, as well as bars, coffee shops and restaurants.[121][122] Expansion of destinations by carrier RwandAir and building of new facilities such as the Kigali Convention Centre has attracted events to Kigali including the African Development Bank's 2014 Annual General Assembly,[120] and a 2018 extraordinary summit of the African Union.[123] The Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting was scheduled to be held in the city in June 2020, with attendees including Charles, Prince of Wales, and national leaders,[124] although this has been postponed as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.[125]

The city's largest employment sector is agriculture, fishing and forestry, representing 24% of the workforce.[111] Farmland comprised over 60% of the land within the city's boundaries in 2012,[72] mostly in the outer areas surrounding the urban core.[126] As is the case nationwide,[127] much of the agriculture in Kigali is subsistence farming on small plots, but there are some larger modern farms close to the city, particularly in Gasabo district, which has the highest average area of cultivated land per household in the country.[128] Other major employment areas in the city are government, which comprises 12% of the workforce, transportation and communication, construction, and manufacturing. The NISR classifies 21% of the workforce as being employed in "other services" such as utilities and financial services,[111] the latter including banking, pensions, insurance, microfinance,[129] and the Rwanda Stock Exchange, which launched in 2011.[130]

Industry in Kigali formed only 14% of the city's GDP in 2014, focused on a small industrial zone set up in the 1970s.[116] Challenges for the sector include the high cost of importing raw materials into a land-locked country, as well as substandard infrastructure and a lack of skilled workers.[131] In 2011, the parliament passed a law establishing special economic zones in Rwanda,[132] the first of which was established in 2014 on Masoro Hill in Gasabo district, close to Kigali International Airport.[133] Companies operating within the zone benefit from good infrastructure, availability of land and transport links, as well as tax breaks. It attracted 61 businesses in its first year of operation, manufacturing products such as paper and foam mattresses.[131] As the zone grew over subsequent years, further businesses relocated there from other parts of the capital such as the Gikondo Industrial Park.[133] The city sits close to deposits of cassiterite, an ore used to obtain tin, as well as tungsten. Cassiterite is mined in the town of Rutongo, around 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of Kigali,[134] while tungsten is mined at Nyakabingo, a similar distance away.[135] Much of the raw mineral is exported out of Rwanda for processing, but there are some local processing facilities.[136] This includes the Karuruma smelter in the northern suburbs of Kigali, which was built in the 1980s and was able to produce up to 1,800 tonnes (1,800 long tons; 2,000 short tons) of pure tin per year as of 2019.[137]

Governance and politics

Kigali is a province-level city, one of the five provinces of Rwanda. The area under the city's jurisdiction has been expanded several times since Rwandan independence,[104] the current boundaries being established through a 2005 law as part of local-government restructuring. The law gave the city government responsibility for strategic planning and urban development, as well as liaising with the three constituent districts and monitoring the districts' development plans.[138] Like other provinces, Kigali is divided into districts—Gasabo, Kicukiro, and Nyarugenge—which are in turn divided into 35 sectors.[1]

From January 2020 a new administrative system for Kigali was introduced, after a law was passed by the national parliament the previous year.[139] Under the previous system, in effect since 2002, power was significantly devolved to the districts which were led by their own mayors, managing infrastructure and levying taxes, around 30% of which were passed to the city-wide authority.[140] The changes, implemented with the goal of reducing bureaucracy and inefficiency,[139] gave the city council much greater power including control of the budget.[141] The districts ceased to be separate legal entities, their mayors being replaced by district executive administrators appointed by the national government.[142]

The city council is composed of eleven individuals, down from 33 in the old system.[141] Six of the council members are directly elected by the public, each district electing one man and one woman. The remaining five members are appointed by the President of Rwanda, subject to the approval of the cabinet. Each council member serves for a renewable five-year term.[143] The executive branch of the city government is headed by the mayor, who is elected via a complex electoral college system, with the electorate voting for delegates at the sub-sector village level, who go on to elect other delegates through each level of the administrative hierarchy.[140] The mayor and two deputy mayors form the executive committee, which reports to the council and implements its decisions.[144] As of 2021 the incumbent mayor is Pudence Rubingisa, who is also leader of the Kigali branch of the ruling RPF party.[145][146] Notable past mayors include Francois Karera, who held the post from 1975 to 1990 under the presidency of Juvénal Habyarimana, and Rose Kabuye, who had fought with the RPF during the Rwandan Civil War and was the first post-genocide mayor from 1994 to 1997.[147] Day-to-day budget and staff management are the responsibility of a city manager,[148] appointed by the prime minister.[141]

In addition to the city government, most Rwandan government offices are located in Kigali, particularly in the suburbs of Kacyiru and Kimihurura.[149] This includes Village Urugwiro in Kacyiru, which is the office of the president,[150] and the Chamber of Deputies and Senate in Kimihurura.[151]

Crime and policing

In common with the rest of the country, policing in Kigali is provided by the Rwanda National Police (RNP).[152] The city falls within RNP's central division, which is headed as of 2020 by Assistant Commissioner of Police Felly Rutagerura Bahizi.[153][154] The United States government's Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC) praises the RNP's professionalism, but notes that it lacks specialist skills in dealing with policing tasks such as investigation, counter-terrorism, bomb disposal, and forensics. OSAC also notes that the RNP has limited resources on the ground, stating that police are often "unable to respond to an emergency call in a timely manner", and that police patrols are more focused on terrorism than crime.[155]

Despite this, Kigali has a reputation for being a relatively safe city. The Lonely Planet guidebook describes it as "a genuine contender for the safest capital in Africa", while Bert Archer of BBC Travel described it as "clean and safe".[156] In a 2015 interview with The New Times, then-commander of the central division Rogers Rutikanga cited "efficient operations and daily surveillance" as the means by which the city was policed. Rutikanga noted that there were crimes related to burglary, drugs, assault and robbery, as well as petty crime and pickpocketing, but that numbers were kept low through community policing and engagement with schools, businesses, municipal government and social service providers.[157] In its advice to overseas visitors, OSAC states that there is a "moderate risk from crime in Kigali", but notes that such crime is rarely violent. It cites pickpocketing and petty theft as the biggest concerns for foreigners within the city.[155] Rwanda as a whole has lower crime rates than other countries in East Africa. In 2014–15, the number of intentional homicides per 100,000 people was 2.52 in the country, compared with 11.52 for Uganda, 6.95 for Tanzania, 4.79 for Kenya, and 4.52 for Burundi.[158]

Although the constitution allows freedom of assembly, with protests and demonstrations allowed with a permit, such gatherings in Rwanda are rare. The US political freedom research institute Freedom House states that fear of arrest serves as a deterrent for most such protests, and that the police often disperse protests even when they have official permission.[155][159] Those gatherings which do take place are mostly peaceful and crime-free. OSAC's report assesses the city's terrorism risk as "minimal".[155]

Culture

Kigali was not historically the hub of Rwanda's cultural heritage. For example, the country's traditional dance, a choreographed routine consisting of three components, originated in the royal court at Nyanza.[160] However, the capital is now home to many groups which perform the dance including the LEAF community arts troupe,[161] whose founding members were eighteen homeless orphaned children,[162] and Indatirwabahizi, a cultural troupe affiliated with the city government.[163] Drums are of great importance in traditional Rwandan music; the royal drummers enjoyed high status within the court of the mwami. Drummers play together in groups of varying sizes, usually between seven and nine in number.[164] Traditional music and songs are performed in venues across the city by acts such as the Gakondo Group led by Massamba Intore.[165] Rwanda and Kigali have a growing popular music industry, influenced by African Great Lakes, Congolese, and American music. The most popular genre is hip hop, with a blend of dancehall, rap, ragga, R&B and dance-pop.[166] Since 2011, the Kigali Up music festival has been held annually in July or August.[167] Artists from Rwanda and other countries perform music in a variety of styles including reggae and blues, with audiences of several thousand. Some of the musicians also give lessons to attendees during the festival. The Hobe Rwanda Festival, held in September, features music as well as dance and local art.[168]

A number of films about the Rwandan genocide have been filmed in Kigali, including 100 Days, Sometimes in April, Shooting Dogs and Shake Hands with the Devil. Others, such as Hotel Rwanda were set in the city, but filmed in other countries. Several of the films featured survivors as cast members.[169][170] Kigali also has a growing domestic film industry which began in the early 2000s with the Rwanda Film Centre, founded by journalist Eric Kabera. One of the centre's goals was to diversify the subjects covered by Rwandan films beyond the genocide theme, presenting other aspects of the country.[171] In 2005, Kabera inaugurated the Rwanda Film Festival which takes place annually at venues in the capital and elsewhere,[172] giving it the nickname "Hillywood", a portmanteau word combining Rwanda's nickname "land of a thousand hills" with Hollywood.[171] The term is also used for Rwanda's film industry in general.[173]

On Genocide Memorial Day, a national holiday observed every year on 7 April, the Kigali Genocide Memorial hosts Kwibuka, during which the president lights a "flame of hope" and addresses the nation.[174] This is followed by an official week of mourning and, on 4 July, the Liberation Day holiday.[175] Along with the rest of Rwanda, the last Saturday of each month in Kigali is umuganda, a morning of mandatory community service lasting from 8 am to 11 am.[16] All able bodied people between 18 and 65 are expected to carry out community tasks such as cleaning streets or building homes for vulnerable people. Most normal services close down during umuganda, and public transportation is limited.[176]

Kigali's cuisine is similar to that of the rest of the country.[177] For those reliant on subsistence agriculture, local staple foods include bananas, plantains (known as ibitoke), pulses, sweet potatoes, beans, and cassava (manioc).[178] These staple foods are also served in restaurants across the city, often as part of a mélange – a self-service buffet meal which can also include meat, chips or fish.[179] Cassava leaves are often combined with onions and stock to make isombe, a stew dish which originated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[177] Brochettes are the most popular food when eating out in the evening, usually made from goat but sometimes tripe, beef or fish.[179] The most popular fish are tilapia as well as sambaza, a small sardine-like animal which is obtained mostly from Lake Kivu.[177][180] The city has restaurants serving dishes from outside the country, including Chinese, French, Italian and Indian.[179] Popular drinks include ikivuguto, a fermented milk, and banana beer.[177]

Education

In colonial and pre-genocide Rwanda, Butare was the country's principal centre for tertiary education. Early colleges such as the Nyakibanda Major Seminary, founded in 1936, and three 1960s establishments including the National University of Rwanda (UNR), were all located in the southern city.[181][182][183] The first higher-education institution in Kigali was the Institut Africain et Mauricien de statistique et d'économie appliquée, which was founded in 1976,[181][184] but the city did not become a major centre of learning until the second half of the 1990s. At that time, the public Kigali Health Institute (KHI), Kigali Institute of Science and Technology (KIST), and Kigali Institute of Education (KIE) were founded, along with private universities the Kigali Independent University (ULK) and the University of Lay Adventists of Kigali (UNILAK).[181] Further institutions were added in Kigali in the 21st century, including the public School of Finance and Banking (SFB) in Gikondo and the private University of Kigali,[185] as well as branches of foreign universities such as Mount Kenya University and Carnegie Mellon University's college of engineering.[186][187][188] As of 2018, there were a total of 50,594 students enrolled at tertiary institutions in Kigali, with a total of 28 separate campuses.[189]

In 2013 the government implemented significant changes in the country's public university system, intended to improve efficiency by removing duplicated courses of study and eliminating discrepancies in student assessment between the different schools. The previously-independent Kigali institutions KHI, KIST, KIE and SFB were merged with three others from outside the city—the UNR, Nyagatare-based Umutara Polytechnic and Ruhengeri's Higher Institute of Agriculture and Animal Husbandry—creating the consolidated University of Rwanda. It has six constituent colleges,[190] spanning nine campuses, three of which are in Kigali. These are the Gikondo campus, which serves as the university's headquarters and is home to its business and economics programmes, the Nyarugenge campus on the former KIST site, which houses the sciences, architecture and engineering, and the Remera campus which covers medicine, nursing, dentistry and health sciences.[191][192]

In 2018 Kigali had 239 primary schools with 203,680 pupils enrolled,[193] and 143 secondary schools with an enrolment of 60,997.[194] The large rate of drop-out between primary and secondary, a phenomenon which occurs across Rwanda, is attributed by the Ministry of Education and UNICEF to insufficient numeracy and English skills in primary-school finishers, cost, the need for children to contribute to household labour, and insufficient teaching resources.[195] The city's three districts occupied the top positions in the national table of exam results at primary level in 2019, although this success was not replicated at secondary level in which rural districts were the top performers. The top-three performing individual secondary schools offering the Rwandan syllabus—FAWE Girls' School, Petit Séminaire St Vincent de Ndera, and Lycée Notre-Dame de Cîteaux—were all in Kigali, however.[196] The city also has a number of private schools, which target wealthy Rwandans and expatriates, including the Green Hills Academy, École Belge, and the International School of Kigali. These schools, which charge high fees, offer international programmes such as the International General Certificate of Secondary Education and the International Baccalaureate which enable students to study at universities worldwide.[197]

Sport

The largest sports venue in Kigali is Amahoro Stadium, in the Remera area of the city, which was built in the 1980s and has a capacity of 30,000.[198][199] The stadium is used primarily for association football, playing host to most Rwanda national football team home games as well as domestic fixtures.[200] It was one of four stadia used for fixtures in the 2016 African Nations Championship including the final, in which the Democratic Republic of the Congo beat Mali.[201][202] The stadium also hosts rugby union fixtures, including those of the national team,[203] as well as concerts and public events.[204] The Amahoro complex includes an indoor venue, commonly known by the French name Petit stade, and a Paralympic playing hall.[205] The Kigali Arena is a 10,000-capacity indoor arena next to Amahoro Stadium, which opened in 2019.[206] The arena hosts sports such as basketball, including the upcoming AfroBasket 2021 tournament,[207] as well as handball, volleyball, and tennis.[208] Other venues in the city include the 22,000-capacity Nyamirambo Regional Stadium and the Rwanda Cricket Stadium in Gahanga, which opened in 2017.[209][210] Rwanda's only golf course, the Kigali Golf Club, is based in Nyarutarama;[211] as of 2020 it is being expanded to eighteen holes and hopes to attract regional tournaments in future.[212]

Seven of the sixteen teams in the association football Rwanda Premier League are based in Kigali. Most of these do not have their own stadia and play fixtures at multiple venues including Amahoro Stadium, Nyamirambo Regional Stadium and various smaller grounds.[209] The country's two most successful teams are based in the city – APR FC, who have won seventeen championships since 1994, and Rayon Sports, who won seven in the same period.[213][214] As of 2020, ten of the fourteen teams in Rwanda's National Basketball League play their home games in Kigali, with venues including Club Rafiki and the Integrated Polytechnic Regional College Kigali, as well as the Amahoro Stadium's Petit stade and the Kigali Arena.[215][nb 4] This includes the two most successful clubs Patriots BBC and Espoir BBC, who have won four titles each.[217][218]

Transportation

The Rwandan government has increased investment in the transport infrastructure of Rwanda since the 1994 genocide, with aid from the United States, European Union, Japan, and others. Kigali is the centre of the country's road network, with paved roads linking the city to most other major cities and towns in the country.[219] It is also connected by road to other countries in the East African Community, namely Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi and Kenya, as well as to the eastern Congolese cities of Goma and Bukavu; the most important trade route for imports and exports is the road to the port of Mombasa via Kampala and Nairobi, which is known as the Northern Corridor.[220] Within the city there was a total of 1,017 kilometres (632 mi) of road in 2012, although only fourteen per cent of this was paved road and many of the unpaved sections were of poor quality and dangerous during rainfall. The authorities have been making gradual improvements since the 1990s, increasing the quality of the surfaces and also upgrading most of the city's arterial routes to dual-carriageway.[221][222]

Car ownership in Kigali is low, with just six per cent of households possessing one as of 2011.[221] Most residents therefore rely on public transport for journeys within the city and elsewhere. Historically most passenger journeys within Kigali were in minibuses, operating under a share taxi system with sixteen passengers per bus.[223] In the 2010s these were phased out in many areas of the city, in favour of larger buses,[224] some of which permit cashless payment through a "Tap & Go" card and online bookings.[225][226] Motorcycle taxis are the most popular private-hire vehicle with an estimated twenty to thirty thousand vehicles operating in Kigali. The government has announced plans to replace the country's fleet of petrol-powered motorcycles with electric vehicles,[227] and online booking and metering has been rolled out for both motorcycles and taxicabs in recent years, such as Yego Cab and Move Ride by Volkswagen.[228][229][230] Bicycle taxis operate in some areas of the city, being reintroduced in 2014 after a period in which they were banned.[231][232]

International coaches run from Nyabugogo to other destinations in East Africa. Until 2019, this included the Ugandan capital Kampala, which was reached either via Gatuna and Kabale or via Kagitumba.[233][234] The journey via Gatuna on the overnight service takes around ten hours.[233] Some Kampala services continued to Nairobi in Kenya.[235] In 2019 the Rwanda–Uganda border was closed by the Rwandan government amid a diplomatic dispute over rebel groups and the treatment of Rwandan nationals in Uganda.[236] Some travellers began using the Rusomo Falls border crossing to reach Kampala via Tanzania, a much longer journey.[237] As of 2020 Rwanda has no railways, but the government has agreed with Tanzania to construct a standard-gauge railway linking Kigali to Isaka, where passengers could connect with either the Central Line or with the future Tanzania Standard Gauge Railway, to reach Dar-es-Salaam.[238]

Kigali International Airport (KIA), in the eastern suburb of Kanombe, is the nation's and the city's principal airport. The busiest routes are those to Jomo Kenyatta International Airport in Nairobi and Entebbe International Airport, which serves Kampala;[239] there is one domestic route, between Kigali and Kamembe Airport near Cyangugu.[240] With capacity for growth at KIA limited, the government commissioned the new Bugesera International Airport, 25 kilometres (16 mi) south-east of Kigali,[241] with construction beginning in 2017. It will become the country's largest when it opens, complementing the existing Kigali airport.[242] The national carrier is RwandAir, and the country is served by seven foreign airlines.[239]

Notes

- From NISR 2012a, p. 6: 586,123 / 1,132,686 = 51.7%

- From NISR 2012a, p. 64: Sum of columns up to 45–49, and divide by 1,132,686

- Total GDP calculated as sum of Gasabo, Kicukiro and Nyarugenge districts: $925,037,044 + $537,601,961 + $371,304,245 = $1,833,943,250.[117] Per-capita figure assumes a city population of 1,132,686.[100]

- From.[216] Four teams play home games outside Kigali – RP-IPRC Huye BBC and UR BBC-MEN (Butare), RP IPRC MUSANZE (Ruhengeri), and RUSIZI Basketball Club (Cyangugu). The remaining ten teams all play games at Kigali venues Club Rafiki, Kigali Arena, NPC, Petit stade Remera, and RP-IPRC Kigali.

References

- REMA 2013, p. 11.

- "Global Data Lab: Sub-national HDI". Institute for Management Research, Radboud University. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Chrétien 2003, p. 44.

- Mamdani 2002, p. 61.

- Chrétien 2003, p. 58.

- Dorsey 1994, p. 37.

- Munyakazi & Ntagaramba 2005, p. 18.

- Prunier 1999, p. 18.

- "Muhazi". Rwanda Development Board. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2018 – via RwandaTourism.com.

- Dorsey 1994, p. 6.

- Chrétien 2003, p. 158.

- Streissguth 2007, pp. 21–22.

- Dorsey 1994, p. 39.

- Twagilimana 2015, p. 175.

- Cybriwsky 2013, pp. 140–141.

- Richardson, Heather (13 March 2019). "Kigali city guide: where to eat, drink, shop and stay in Rwanda's charming capital". The Independent. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Mainstory: Kigali City through history". The New Times. 24 November 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 218.

- Carney 2013, p. 24.

- Tabaro, Jean de la Croix (6 July 2014). "The story of Kandt and how Kigali came to be the capital city". The New Times. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Louis 1963, p. 146.

- Ntagungura, Godfrey (20 May 2011). "The history of City of Kigali". The New Times. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Mbanda, Gerald (16 September 2014). "The Legacy of Dr. Richard Kandt (Part I)". The New Times. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Institute of National Museums of Rwanda". National Museums of Rwanda. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Louis 1963, p. 168.

- Dorsey 1994, p. 46.

- Linden & Linden 1977, p. 103.

- Louis 1963, p. 172.

- Linden & Linden 1977, p. 110.

- Stapleton 2013, p. 164.

- Prunier 1999, pp. 25–26.

- Linden & Linden 1977, p. 127.

- Des Forges 2011, p. 135.

- Des Forges 2011, pp. 137–138.

- Linden & Linden 1977, p. 130.

- Des Forges 2011, p. 142.

- Dorsey 1994, p. 275.

- Des Forges 2011, p. 210.

- Geary 2003, p. 96.

- Stapleton 2017, p. 34.

- "Ruanda Urundi / Preface by Jean-Paul Horroy, governor of Ruanda-Urundi". Infor Congo (Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi Information and Public Relations Office). 1958. OCLC 782062177.

- Muramila, Gasheegu. "100 mayors for City centenary celebrations". The New Times. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- "History in Huye (Butare)". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- REMA 2013, p. 21.

- Mohr, Charles (7 July 1973). "Rwanda Coup Traced to Area Rivalry and Poverty". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Linden, Ian (11 August 1973). "Rwanda's quiet coup". The Tablet. p. 3. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Military Coup in Rwanda Follows Tribal Dissension". The New York Times. Associated Press. 6 July 1973. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- Prunier 1999, p. 61.

- "Cable: Rwanda Coup". United States Department of State. 11 July 1973. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Prunier 1999, p. 175.

- Dallaire 2005, p. 130.

- "Hutus 'killed Rwanda President Juvenal Habyarimana'". BBC News. 12 January 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Dallaire 2005, p. 386.

- Guichaoua, André (2020). "Counting the Rwandan Victims of War and Genocide: Concluding Reflections". Journal of Genocide Research. 22 (1): 125–141. doi:10.1080/14623528.2019.1703329. S2CID 213471539. 500,000–800,000 is the range of scholarly estimates listed on the third page of the paper.

- "Rwanda: How the genocide happened". BBC News. 7 May 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Dallaire 2005, pp. 264–265.

- Dallaire 2005, p. 288.

- Dallaire 2005, p. 299.

- Dallaire 2005, p. 421.

- Dallaire 2005, p. 459.

- "Official holidays". Government of Rwanda. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- REMA 2013, p. viii.

- Doherty, Killian (19 May 2014). "The Metamorphosis of Post-Genocide Kigali". Failed Architecture. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Topping, Alexandra (4 April 2014). "Kigali's future or costly fantasy? Plan to reshape Rwandan city divides opinion". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ""Why Not Call This Place a Prison?" – Unlawful Detention and Ill-Treatment in Rwanda's Gikondo Transit Center". Human Rights Watch. 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- CIA 2007, p. 479.

- "Time in Rwanda now: Time zone". Time.is. Digitz.no. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- "Rwanda redrawn to reflect compass". BBC News. 3 January 2006. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Kigali at a Glance". City of Kigali. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- REMA 2013, pp. 7–8.

- "Rwanda/Burundi Travel Map" (Map). International Travel Maps and Books. ITMB Publishing. 2007. ISBN 978-1-55341-380-6.

- REMA 2013, p. 7.

- REMA 2013, p. 5.

- "Team reaches Nile's 'true source'". BBC News. 31 March 2006. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- REMA 2013, p. 4.

- REMA 2013, p. 6.

- REMA 2013, p. 8.

- REMA 2013, p. 9.

- Kanamugire, Johnson (26 January 2017). "Kigali businesses brace for residential to city centre move". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- Mwai, Collins (26 October 2017). "Tourism and hospitality establishments get star grading". The New Times. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "University Teaching Hospital of Kigali". Google Maps. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "UR College of Science and Technology". Google Maps. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "National Bank of Rwanda". Google Maps. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning". Google Maps. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Gateway to gorillas: A guide to Kigali". The Week. 21 August 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Tabaro, Jean de la Croix (24 July 2014). "Know Your History: The birth of Nyamirambo". The New Times. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Nyamirambo: Kigali's coolest neighbourhood". Rough Guides. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (28 June 2013). "Nyabugogo: Where idlers lurk!". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Malonza, Josephine (20 October 2015). "The Post-Kiyovu symmetry: A critical analysis". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Gregg, Emma (8 March 2020). "Kigali: how creativity has transformed the Rwandan capital". National Geographic. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Tashobya, Athan (11 October 2017). "Photos: The changing face of Lower Kiyovu". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (23 May 2013). "Kabagali: The raggedy side of Kacyiru". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "Kigali Genocide Memorial: Getting There". Kigali Genocide Memorial. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Asiimwe, Geoffrey (16 August 2015). "Rwanda Golf Union building new luxury country club". The New Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Twagilimana 2015, p. 217.

- "Background Note: Rwanda". United States Department of State. 2004. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "World Weather Information Service – Kigali". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- King 2007, p. 10.

- "Blue Peace for the Nile" (PDF). Strategic Foresight Group. 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- NISR 2012a, p. 10.

- NISR 2012a, p. 15.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (26 July 2007). "Kigali, vast area through 100 years". The New Times. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- "State of the Art Report for RurbanAfrica, Work Package 3: City Dynamics" (PDF). UCPH Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management. pp. 2–4. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- REMA 2013, p. 1.

- REMA 2013, p. 24.

- REMA 2013, p. 29.

- NISR 2012b, pp. 107–108.

- NISR 2012b, pp. 97–99.

- NISR 2012b, pp. 125–127.

- UNDP 2015, p. 32.

- REMA 2013, p. 30.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". UNDP. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "Rwanda Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- NISR 2014, p. 19.

- Bafana, Busani. "Kigali sparkles on the hills". Africa Renewal. United Nations. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Bundervoet et al. 2017, p. 18.

- Bundervoet, Maiyo & Sanghi 2015, pp. 21–23.

- World Bank 2016, p. 14.

- REMA 2013, p. 37.

- Mwijuke, Gilbert (18 July 2015). "Kigali steadily grows as a hub for meetings, conferences and exhibitions". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Kamin, Debra (12 January 2018). "36 Hours in Kigali, Rwanda". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Hitimana, Emmanuel (2 December 2018). "Rwanda to Build Ecotourism Park in Kigali". Inter Press Service. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Bizimungu, Julius (27 December 2018). "2018 in review: Rwanda on track to become a meetings, conferences hub". The New Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Furness, Hannah (11 July 2019). "We have 18 months to save world, Prince Charles warns Commonwealth leaders". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Postponement of CHOGM 2020 due to Covid-19". Commonwealth of Nations. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- REMA 2013, p. 47.

- "Rwanda's agricultural revolution is not the success it claims to be". The Conversation. 13 December 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "EICV3 District Profile: Kigali – Gasabo". National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda. 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Investment opportunities: Financial services". Rwanda Development Board. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Vision,Mission,and Values". Rwanda Stock Exchange. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Manson, Katrina (24 April 2015). "Businesses relocate to Rwanda's new Special Economic Zone". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Kigali Special Economic Zone ready, official says". The New Times. 1 August 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Kigali Special Economic Zone impacts Rwanda's industrial growth". The New Times. 1 June 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Cassiterite from Nyamiumba Mine, Rutongo area, Kigali City Province, Rwanda". Mindat.org. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- "Nyakabingo Mine, Kigali, Kigali City Province, Rwanda". Mindat.org. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Esiara, Kabona (28 October 2018). "Despite pressure, govt will not ban raw mineral exports". Rwanda Today. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Investing in a smelter in Rwanda". Mining Review Africa. 26 September 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Rwanda Decentralization Strategic Framework". Ministry of Local Government (Rwanda). August 2007. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Mutanganshuro, Lavie (20 January 2020). "Kigali City starts operating under new structure". The New Times. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Ndereyehe, Celestin (18 April 2019). "New Kigali City Structure: Districts Lose Budgeting, Planning Role". The Chronicles. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Kigali City Gets Acting Mayor As Government Begins Implementing New Law". The Chronicles. 5 August 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Tabaro, Jean de la Croix (7 February 2020). "Kigali City District Mayors Dropped". KT Press. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Responsibilities of the Council of the City of Kigali". City of Kigali. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "City Leadership: Executive Committee". City of Kigali. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Nkurunziza, Michel. "Over 79,000 Kigali City households get food relief". The New Times. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Kamuzinzi, Simon (25 January 2020). "FPR-Inkotanyi muri Gasabo n'Umujyi wa Kigali batangije inyubako ya miliyari 3.2Frw". Kigali Today (in Kinyarwanda). Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "City of Kigali Mayors since 1994". City of Kigali. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Responsibilities of the City Manager". City of Kigali. Archived from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- "Rwanda government seeks to own its offices". The EastAfrican. 12 February 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Iliza, Ange (30 January 2020). "Kagame receives credentials for 10 new envoys". The New Times. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Karuhanga, James (4 July 2019). "The journey of the Rwandan parliament". The New Times. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Our Mission and Vision". Rwanda National Police. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Our Mission and Vision". Rwanda National Police. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Road safety campaign taken to commercial motorcyclists". The New Times. 14 February 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "Rwanda 2019 Crime & Safety Report". Overseas Security Advisory Council. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Archer, Bert (6 January 2020). "The most inviting city in Africa?". BBC Travel. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Creating a crime-free Kigali". The New Times. 1 March 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- "Intentional Homicide Victims". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Freedom in the World 2020: Rwanda". Freedom House. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "National Ballet – Urukerereza". Rwanda Development Gateway. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Moore, Timothy. "APF Rwanda participants enjoy cultural dinner". United States Air Forces in Europe – Air Forces Africa. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Rosen, Jon (2 November 2010). "Rwanda: Dancing off the streets". The World. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Asiimwe, Geoffrey (24 November 2016). "Five teams set for EAC Local Authorities Sports and Cultural Games". The New Times. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Adekunle 2007, pp. 135–139.

- Buchan, Kit (11 April 2014). "Rwanda reborn: Kigali's culture, heart and soul". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Mbabazi, Linda (11 May 2008). "Hip Hop Dominating Music Industry". The New Times. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Opobo, Moses (17 July 2018). "KigaliUp is back, but..." The New Times. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "Festivals and Events". VisitRwanda.com. Rwanda Development Board. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Fegley 2016, p. 55.

- Milmo, Cahal (29 March 2006). "Flashback to terror: Survivors of Rwandan genocide watch screening of Shooting Dogs". The Independent. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Bloomfield, Steve (30 August 2007). "Welcome to Hillywood: how Rwanda's film industry emerged from genocide's shadow". The Independent. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Briggs & Connolly 2018, p. 106.

- "Hillywood: Telling the Rwandan story on film". The New Times. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Rwandan genocide commemorations dampened by Covid-19 lockdown". Radio France International. 7 April 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Watson, Renzi & Viggiani 2010, p. 25.

- "Umuganda". Rwanda Governance Board. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- Keighran, Mandi (19 February 2020). "A Taste of Kigali: Uniquely Rwandan Dishes". The Culture Trip. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- Adekunle 2007, p. 81.

- Briggs & Booth 2006, pp. 54–55.

- Love, Emma (16 July 2017). "Snap up a silvery delicacy from Lake Kivu, Rwanda". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- World Bank 2004, pp. 136–137.

- Ouazani, Cherif (5 April 2004). "Butare, Silicon Valley". Jeune Afrique. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "Item 1 – Institut Pédagogique National du Rwanda, Butaré (RWA.2)". UNESCO Archives AtoM Catalogue. 6 January 1968. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Kiregyera 2015, p. 30.

- "University of Kigali – UoK". University of Kigali. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "The Sun is rising at Kigali's School of Finance and Banking". The New Times. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "Kigali Campus History". Mount Kenya University. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "CMU Africa". Carnegie Mellon University Africa. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- MINEDUC 2018, p. 112.

- Lemarchand & Tash 2015, p. 162.

- "Admissions – Information Centers". University of Rwanda. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "UR Campus Distribution of Programmes". University of Rwanda. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- MINEDUC 2018, pp. 101–103.

- MINEDUC 2018, pp. 105–107.

- MINEDUC & UNICEF 2017, p. xvi.

- Mugisha, Emmanuel Côme (31 December 2019). "National exams: Kigali dominates in primary as rural schools dominate in high school". The New Times. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "The era of elite international schools is here". The New Times. 1 May 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "卢旺达国家体育场项目" (in Chinese). China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Mutale, Chama (7 January 2016). "Uganda/Zimbabwe: Zambia to Face Zimbabwe, Uganda At Umuganda Stadium". Zambian Watchdog. Retrieved 21 May 2020 – via AllAfrica.

- "Amavubi Background". Rwanda Football Federation. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Orange African Nations Championship, Rwanda 2016: Venues". Confederation of African Football. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "DR Congo win second CHAN title with 3–0 win over Mali". France 24. 7 February 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Working as a team is a key for a new committee to be successfull [sic]". Rwanda Rugby Federation. 11 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Andiva, Yvonne (22 June 2018). "Rwanda set to renovate Amahoro National Stadium". Construction Review Online. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Yanditswe (4 February 2020). "Amahoro Stadium to be revamped and expanded". Rwanda Broadcasting Agency. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- Kagire, Edmund (25 September 2019). "Now President Kagame Wishes Kigali Arena Had 20, 000 Capacity". Kigali Today. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Sikubwabo, Damas (8 October 2019). "Dates for Rwanda Afrobasket 2021 confirmed". The New Times. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Construction of modern multi-sport arena kicks-off". Rwanda Housing Authority. 17 January 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- "Rwanda – National Soccer League – Venues". Soccerway. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Thousands to grace Gahanga Cricket Stadium inauguration". The New Times. 18 October 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Opobo, Moses (7 February 2018). "Could golf be the new tourism frontier for Rwanda?". The New Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- "Gary Player Design completely revamps Kigali course to 18 holes". Golf Course Architecture. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Kagire, Edmund (19 May 2018). "Rwanda's Rayon Sport aiming for top honours". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- Schöggl, Hans (1 October 2015). "Rwanda – List of Champions". RSSSF. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- "Rwandan Basketball (Men) Teams". AfroBasket. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Schedule". Rwanda Basketball Federation. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "Patriots Basketball Club – History". AfroBasket. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Espoir BBC Kigali basketball team – History". AfroBasket. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- African Development Bank & OECD 2006, p. 439.

- Tancott, Glen (30 June 2014). "Northern corridor". Transport World Africa. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- REMA 2013, p. 72.

- "Kigali roads expansion project starts in January". The New Times. 28 December 2016. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- REMA 2013, p. 70.

- "Bus modernisation drives Kigali residents to 'despair'". France 24. 16 February 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Could cashless payments make Rwanda's bus conductor redundant?". BBC News. 12 April 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Kuteesa, Hudson (26 November 2019). "Featured: Navigating the new Tap & Go System step by step". The New Times. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Bright, Jake (28 August 2019). "Rwanda to phase out gas motorcycle taxis for e-motos". TechCrunch. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Kam, Isaac (1 March 2019). "Volkswagen Launches Ride Hailing Service In Rwanda". Taarifa.rw. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- Bizimungu, Julius (12 September 2017). "YegoMoto makes travel easier". The New Times. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Buningwire, Williams (18 September 2018). ""YEGO Cab" – A New 'Low Cost' Taxi- Service Launched In Kigali". KT Press. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "City, Traffic Police finally give way to cycle-taxis". The New Times. 29 November 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Ngabonziza, Dan (3 August 2016). "After Kagame Intervention Bicycle Taxis Generate Rwf3.6Billion". KT Press. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- "A Visit to Mfashumwana a.k.a. Kyererezi Village". The New Times. 31 July 2010. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "Transporters count losses on Chrismas". The New Times. 25 December 2013. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Agutamba, Kenneth (20 November 2016). "Who cares for East Africa's road travelers?". The New Times. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Mohamed, Hamza (20 February 2019). "Will Kagame and Museveni resolve their dispute?". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- Mugisha, Ivan R. (17 August 2019). "A Rwandan's long journey to Uganda through Tanzania". The EastAfrican. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- "What Is Happening With The Isaka-Kigali Railway?". The Chronicles. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "RwandAir plans further regional expansion in 2015 and launch of long-haul services in 2017". CAPA - Centre For Aviation. Aviation Week Network. 22 December 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- Tumwebaze, Peterson (13 June 2015). "Kamembe airport reopens to flights". The New Times. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "Kigali Bugesera International Airport". Centre for Aviation. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "New Bugesera International Airport construction works kick-off". Ministry of Infrastructure (Rwanda). 9 August 2017. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

Bibliography

- Adekunle, Julius (2007). Culture and customs of Rwanda. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-33177-0.

- African Development Bank; OECD (2006). African Economic Outlook (5th ed.). OECD Publishing. ISBN 978-92-64-02243-0.

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Briggs, Philip; Booth, Janice (2006). Rwanda – The Bradt Travel Guide (3rd ed.). Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-841621-80-7.

- Briggs, Phillip; Connolly, Sean (2018). Rwanda. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 978-1-78477-096-9.

- Bundervoet, Tom; Maiyo, Laban; Sanghi, Apurva (October 2015). "Bright Lights, Big Cities: Measuring National and Subnational Economic Growth in Africa from Outer Space, with an Application to Kenya and Rwanda". SSRN 2682850.

- Bundervoet, Tom; Parby, Jonas Ingemann; Nakamura, Shohei; Choi, Narae (December 2017). "Reshaping urbanization in Rwanda : economic and spatial trends and proposals – note 1 : urbanization and the evolution of Rwanda's urban landscape" (PDF). World Bank Group. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- Carney, J.J. (2013). Rwanda Before the Genocide: Catholic Politics and Ethnic Discourse in the Late Colonial Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-998227-1.

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) (2007). The World Factbook 2007. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-078580-1.

- Chrétien, Jean-Pierre (2003). The Great Lakes of Africa: Two Thousand Years of History. MIT Press. ISBN 978-1-890951-34-4.

- Cybriwsky, Roman A. (2013). Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9.

- Dallaire, Roméo (2005). Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. Arrow. ISBN 978-0-09-947893-5.

- Des Forges, Alison (2011). David Newbury (ed.). Defeat is the only bad news: Rwanda under Musinga, 1896–1931. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-28143-4.

- Dorsey, Learthen (1994). Historical Dictionary of Rwanda (1st ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-2820-9.

- Fegley, Randall (2016). A History of Rwandan Identity and Trauma: The Mythmakers' Victims. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-49851944-1.

- Geary, Anthony (2003). In and Out of Focus: Images from Central Africa, 1885–1960. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-85667-552-2.

- King, David C. (2007). Rwanda (Cultures of the World). Benchmark Books. ISBN 978-0-7614-2333-1.

- Kiregyera, Ben (2015). The Emerging Data Revolution in Africa: Strengthening the Statistics, Policy and Decision-making Chain. African Sun Media. ISBN 978-1-920689-56-8.

- Lemarchand, Guillermo A.; Tash, April (2015). Mapping research and innovation in the Republic of Rwanda. UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-100126-0.

- Linden, Ian; Linden, Jane (1977). Church and Revolution in Rwanda (illustrated ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-0671-5.

- Louis, William Roger (1963). Ruanda-Urundi, 1884–1919. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821621-6.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2002). When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-10280-1.

- "Understanding Dropout and Repetition in Rwanda: Full Report" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Republic of Rwanda (MINEDUC) and UNICEF. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "2018 Education Statistics" (PDF). Ministry of Education, Republic of Rwanda (MINEDUC). December 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- Munyakazi, Augustine; Ntagaramba, Johnson Funga (2005). Atlas of Rwanda (in French). Macmillan Education. ISBN 978-0-333-95451-5.</ref>

- "Population size, structure and distribution" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR). 2012a. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Final Results: Main indicators report" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR). 2012b. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Fourth Population and Housing Census, Rwanda, 2012: Socio-cultural characteristics of the population" (PDF). National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (NISR). January 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Prunier, Gérard (1999). The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide (2nd ed.). Fountain Publishers Limited. ISBN 978-9970-02-089-8.

- "Kigali: State of Environment and Outlook Report 2013" (PDF). Rwanda Environment Management Authority (REMA). 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Stapleton, Timothy J. (2013). A Military History of Africa [3 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39570-3.

- Stapleton, Timothy J. (2017). A History of Genocide in Africa. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3052-5.

- Streissguth, Thomas (2007). Rwanda in Pictures (illustrated ed.). Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-8570-1.

- Twagilimana, Aimable (2015). Historical Dictionary of Rwanda (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-5591-3.

- "Population projections" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Watson, Graeme; Renzi, Barbara Gabriella; Viggiani, Elisabetta (2010). Friends and Foes Volume II: Friendship and Conflict from Social and Political Perspectives. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-1993-0.

- Education in Rwanda: Rebalancing Resources to Accelerate Post-conflict Development and Poverty Reduction. Country Studies. World Bank. 2004. doi:10.1596/0-8213-5610-0. ISBN 978-0-8213-5610-4.

- "Rwanda Economic Update" (PDF). World Bank. February 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

External links

![]() Media related to Kigali at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kigali at Wikimedia Commons

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kigali. |