Autonomous communities of Spain

In Spain, an autonomous community (Spanish: comunidad autónoma) is a first-level political and administrative division, created in accordance with the Spanish constitution of 1978, with the aim of guaranteeing limited autonomy of the nationalities and regions that make up Spain.[1][2][3]

| Autonomous communities

Spanish: comunidad autónoma[lower-alpha 1] | |

|---|---|

| Category | Autonomous administrative division |

| Location | |

| Created by | Spanish Constitution of 1978 |

| Created | 1979–1983 |

| Number | 17 (+2 autonomous cities) |

| Populations | Autonomous communities: 316,798 (La Rioja) – 8,414,240 (Andalusia) Autonomous cities: 86,487 (Melilla), 84,777 (Ceuta) |

| Areas | Autonomous communities: 94,223 km2 (36,380 sq mi) (Castile and León) – 1,927 km2 (744 sq mi) (Balearic Islands) Autonomous cities: 4.7 sq mi (12 km2) (Melilla), 7.1 sq mi (18 km2) (Ceuta) |

| Government | Autonomous government |

| Subdivisions | Province Municipality |

Spain is not a federation, but a decentralized[4][5] unitary state.[1] While sovereignty is vested in the nation as a whole, represented in the central institutions of government, the nation has, in variable degrees, devolved power to the communities, which, in turn, exercise their right to self-government within the limits set forth in the constitution and their autonomous statutes.[1] Each community has its own set of devolved powers; typically those communities with stronger local nationalism have more powers, and this type of devolution has been called asymmetrical. Some scholars have referred to the resulting system as a federal system in all but name, or a "federation without federalism".[6] There are 17 autonomous communities and two autonomous cities that are collectively known as "autonomies".[lower-roman 1] The two autonomous cities have the right to become autonomous communities, but neither has yet exercised it. This unique framework of territorial administration is known as the "State of Autonomies".[lower-roman 2]

The autonomous communities are governed according to the constitution and their own organic laws known as Statutes of Autonomy,[lower-roman 3] which define the competences that they assume. Since devolution was intended to be asymmetrical in nature,[7] the scope of competences vary for each community, but all have the same parliamentary structure.[1]

Autonomous communities

R.A: Regionally appointed; D.E: Directly elected.

Autonomous cities

| Flag | Coat of arms | Autonomous city | Mayor-President | Legislature | Government coalition | Senate seats | Area (km²) | Population (2019) | Density (/km²) | GDP per capita (euros) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Melilla | Eduardo de Castro (Cs) | Assembly of Melilla | CpM, PSOE, Cs | 2 (DE) | 12.3 | 86,487 | 7,031 | 16,981 |

|

|

Ceuta | Juan Jesús Vivas (PP) | Assembly of Ceuta | PP | 2 (DE) | 18.5 | 84,777 | 4,583 | 19,335 |

History

Background

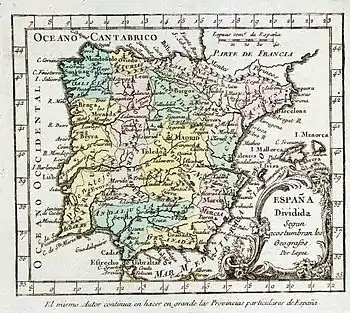

Spain is a diverse country made up of several different regions with varying economic and social structures, as well as different languages and historical, political and cultural traditions.[8][9] While the entire Spanish territory was united under one crown in 1479 this was not a process of national homogenization or amalgamation. The constituent territories—be they crowns, kingdoms, principalities or dominions—retained much of their former institutional existence,[10] including limited legislative, judicial or fiscal autonomy. These territories also exhibited a variety of local customs, laws, languages and currencies until the mid 19th century.[10]

From the 18th century onwards, the Bourbon kings and the government tried to establish a more centralized regime. Leading figures of the Spanish Enlightenment advocated for the building of a Spanish nation beyond the internal territorial boundaries.[10] This culminated in 1833, when Spain was divided into 49 (now 50) provinces, which served mostly as transmission belts for policies developed in Madrid.

Spanish history since the late 19th century has been shaped by a dialectical struggle between Spanish nationalism and peripheral nationalisms,[11][12] mostly in Catalonia and the Basque Country, and to a lesser degree in Galicia.

In a response to Catalan demands, limited autonomy was granted to the Commonwealth of Catalonia in 1914, only to be abolished in 1925. It was granted again in 1932 during the Second Spanish Republic, when the Generalitat, Catalonia's mediaeval institution of government, was restored. The constitution of 1931 envisaged a territorial division for all Spain in "autonomous regions", which was never fully attained—only Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia had approved "Statutes of Autonomy"—the process being thwarted by the Spanish Civil War that broke out in 1936, and the victory of the rebel Nationalist forces under Francisco Franco.[11]

During General Franco's dictatorial regime, centralism was most forcefully enforced as a way of preserving the "unity of the Spanish nation".[11] Peripheral nationalism, along with communism and atheism were regarded by his regime as the main threats.[13] His attempts to fight separatism with heavy-handed but sporadic repression,[9] and his often severe suppression of language and regional identities[9] backfired: the demands for democracy became intertwined with demands for the recognition of a pluralistic vision of the Spanish nationhood.[11][14]

When Franco died in 1975, Spain entered into a phase of transition towards democracy. The most difficult task of the newly democratically elected Cortes Generales (the Spanish Parliament) in 1977 acting as a Constituent Assembly was to transition from a unitary centralized state into a decentralized state[15] in a way that would satisfy the demands of the peripheral nationalists.[16][17] The then Prime Minister of Spain, Adolfo Suárez, met with Josep Tarradellas, president of the Generalitat of Catalonia in exile. An agreement was made so that the Generalitat would be restored and limited competencies would be transferred while the constitution was still being written. Shortly after, the government allowed the creation of "assemblies of members of parliament" integrated by deputies and senators of the different territories of Spain, so that they could constitute "pre-autonomic regimes" for their regions as well.

The Fathers of the Constitution had to strike a balance between the opposing views of Spain—on the one hand, the centralist view inherited from monarchist and nationalist elements of Spanish society,[15] and on the other hand federalism and a pluralistic view of Spain as a "nation of nations";[18] between a uniform decentralization of entities with the same competencies and an asymmetrical structure that would distinguish the nationalities. Peripheral nationalist parties wanted a multinational state with a federal or confederal model, whereas the governing Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD) and the People's Alliance (AP) wanted minimum decentralization; the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) was sympathetic to a federal system.[13]

In the end, the constitution, published and ratified in 1978, found a balance in recognizing the existence of "nationalities and regions" in Spain, within the "indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation". In order to manage the tensions present in the Spanish transition to democracy, the drafters of the current Spanish constitution avoided giving labels such as 'federal' to the territorial arrangements,[19] while enshrining in the constitution the right to autonomy or self-government of the "nationalities and regions", through a process of asymmetric devolution of power to the "autonomous communities" that were to be created.[20][21]

Constitution of 1978

The starting point in the territorial organization of Spain was the second article of the constitution,[22] which reads:

The Constitution is based on the indissoluble unity of the Spanish Nation, the common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards; it recognizes and guarantees the right to self-government of the nationalities and regions of which it is composed and the solidarity among them all.

— Second Article of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

The constitution was rather ambiguous on how this was to take place.[15][23] It does not define, detail, or impose the structure of the state;[17][22] it does not tell the difference between "nation" and "nationality"; and it does not specify which are the "nationalities" and which are the "regions", or the territories they comprise.[22][24] Rather than imposing, it enables a process towards a decentralized structure based on the exercise that these "nationalities and regions" would make of the right to self-government that they were granted.[22] As such, the outcome of this exercise was not predictable[25] and its construction was deliberately open-ended;[13] the constitution only created a process for an eventual devolution, but it was voluntary in nature: the "nationalities and regions" themselves had the option of choosing to attain self-government or not.[26]

In order to exercise this right, the constitution established an open process whereby the "nationalities and regions" could be constituted as "autonomous communities". First, it recognized the pre-existing 50 provinces of Spain, a territorial division of the liberal centralizing regime of the 19th century created for purely administrative purposes (it also recognized the municipalities that integrated the provinces). These provinces would serve as the building blocks and constituent parts of the autonomous communities. The constitution stipulated that the following could be constituted as autonomous communities:[27]

- Two or more adjacent provinces with common historical, cultural and economic characteristics.

- Insular territories.

- A single province with a "historical regional identity".

It also allowed for exceptions to the above criteria, in that the Spanish Parliament could:[27]

- Authorize, in the nation's interest, the constitution of an autonomous community even if it was a single province without a historical regional identity.

- Authorize or grant autonomy to entities or territories that were not provinces.

The constitution also established two "routes" to accede to autonomy. The "fast route" or "fast track",[23] also called the "exception",[22] was established in article 151, and was implicitly reserved for the three "historical nationalities"[7][24][28]—the Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia—in that the very strict requirements to opt for this route were waived via the second transitory disposition for those territories that had approved a "Statute of Autonomy" during the Second Spanish Republic[28] (otherwise, the constitution required the approval of three-fourths of the municipalities involved whose population would sum up at least the majority of the electoral census of each province, and required the ratification through a referendum with the affirmative vote of the absolute majority of the electoral census of each province—that is, of all registered citizens, not only of those who would vote).

The constitution also explicitly established that the institutional framework for these communities would be a parliamentary system, with a Legislative Assembly elected by universal suffrage, a cabinet or "council of government", a president of such a council, elected by the Assembly, and a High Court of Justice. They were also granted a maximum level of devolved competencies.

The "slow route" or "slow track",[23] also called the "norm",[22] was established in article 143. This route could be taken—via the first transitory disposition—by the "pre-autonomic regimes" that had been constituted in 1978, while the constitution was still being drafted, if approved by two-thirds of all municipalities involved whose population would sum up to at least the majority of the electoral census of each province or insular territory. These communities would assume limited competences during a provisional period of 5 years, after which they could assume further competences, upon negotiation with the central government. However, the constitution did not explicitly establish an institutional framework for these communities. They could have established a parliamentary system like the "historical nationalities", or they could have not assumed any legislative powers and simply established mechanisms for the administration of the competences they were granted.[22][24]

Once the autonomous communities were created, Article 145 prohibits the "federation of autonomous communities". This was understood as any agreement between communities that would produce an alteration to the political and territorial equilibrium that would cause a confrontation between different blocks of communities, an action incompatible with the principle of solidarity and the unity of the nation.[29]

The so-called "additional" and "transitory" dispositions of the constitution allowed for some exceptions to the above-mentioned framework. In terms of territorial organization, the fifth transitory disposition established that the cities of Ceuta and Melilla, Spanish exclaves located on the northern coast of Africa, could be constituted as "autonomous communities" if the absolute majority of the members of their city councils would agree on such a motion, and with the approval of the Spanish Parliament, which would exercise its prerogatives to grant autonomy to other entities besides provinces.[30]

In terms of the scope of competences, the first additional disposition recognized the historical rights of the "chartered" territories,[lower-roman 4] namely the Basque-speaking provinces, which were to be updated in accordance with the constitution.[31] This recognition would allow them to establish a financial "chartered regime" whereby they would not only have independence to manage their own finances, like all other communities, but to have their own public financial ministries with the ability to levy and collect all taxes. In the rest of the communities, all taxes are levied and collected by or for the central government and then redistributed among all.

Autonomic pacts

The Statutes of Autonomy of the Basque Country and Catalonia were sanctioned by the Spanish Parliament on 18 December 1979. The position of the party in government, the Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD), was that only the three "historical nationalities" would assume full competences, while the rest would accede to autonomy via article 143, assuming fewer powers and perhaps not even establishing institutions of government.[32] This was firmly opposed by the representatives of Andalusia, who demanded for their region the maximum level of competences granted to the "nationalities".[24][33]

After a massive rally in support of autonomy, a referendum was organized for Andalusia to attain autonomy through the strict requirements of article 151, or the "fast route"—with UCD calling for abstention, and the main party in opposition in Parliament, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) calling for a vote in favour.[24] These requirements were not met, as in one of the eight provinces, Almería, votes in favour — although the plurality — did not amount to half of the electoral census as required. Yet, in general, the results of the referendum had been clear and unequivocal.[22]

After several months of discussion, the then prime minister of Spain, Adolfo Suárez and the leader of the opposition, Felipe González, reached an agreement to resolve the Andalusian issue, whereby the Parliament approved an amendment to the law that regulated referendums, and used a prerogative of article 144c of the constitution, both actions which combined would allow Andalusia to take the fast route. They also agreed that no other region would take the "fast route", but that all regions would establish a parliamentary system with all institutions of government.[24] This opened a phase that was dubbed as café para todos, "coffee for all".[7] This agreement was eventually put into writing in July 1981 in what has been called the "first autonomic pacts".[23]

These "autonomic pacts"[lower-roman 5] filled in the gap left by the open character of the constitution. Among other things:[22][34]

- They described the final outline of the territorial division of Spain, with the specific number and name of the autonomous communities to be created.

- They restricted the "fast-route" to the "historical nationalities" and Andalusia; all the rest had to take the "slow-route".

- They established that all autonomous communities would have institutions of government within a parliamentary system.

- They set up a deadline for all the remaining communities to be constituted: 1 February 1983.

In the end, 17 autonomous communities were created:

- Andalusia, and the three "historical nationalities"—the Basque Country, Catalonia and Galicia—took the "fast-route" and assumed the maximum level of competences immediately; the rest took the "slow route".

- Aragon, Castilla-La Mancha, Castile and León, Extremadura and the Valencian Community acceded to autonomy as communities integrated by two or more provinces with common historical, economic and cultural characteristics.

- The Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands acceded to autonomy as insular territories, the latter integrated by two provinces.

- Principality of Asturias, Cantabria, La Rioja and Murcia acceded to autonomy as single provinces with historical identity (also called "uniprovincial" autonomous communities).

- Navarre, as a single province, acceded to autonomy through the recognition, update and improvement of its historical and local "law" (charters; Spanish fueros), and as such, it is known as a "chartered community".

- The province of Madrid, home to the national capital, was removed from Castilla-La Mancha (formerly New Castile), to which it previously belonged, and constituted as a single-province autonomous community in the "national interest", the Community of Madrid.

Special provisions were made for the Valencian Community and the Canary Islands in that, although they took the "slow route", through the subsequent approval of specific organic laws, they were to assume the maximum level of competences in less than 5 years, since they had started a process towards the "fast route" prior to the approval of the "autonomic pacts".

On the other hand, Cantabria and La Rioja, although originally part of Old Castile—and both originally included in the "pre-autonomic regime" of Castile and León—were granted autonomy as single provinces with historical identity, a move supported by the majority of their populations.[11][24][35] The "autonomic pacts" give both Cantabria and La Rioja the option of being incorporated into Castile and León in the future, and required that the Statutes of Autonomy of all three communities include such a provision.[34] León, a historical kingdom and historical region of Spain, once joined to Old Castile to form Castile and León, was denied secession to be constituted as an autonomous community on its own right.[36]

_14.jpg.webp)

During the second half of the 1980s, the central government seemed reluctant to transfer all competences to the "slow route" communities.[16] After the five years set up by the constitution, all "slow route" communities demanded the maximum transfer guaranteed by the constitution. This led to what has been called the "second autonomic pacts" of 1992, between the then prime minister of Spain Felipe González from PSOE and the leader of the opposition, José María Aznar from the newly created People's Party (PP) successor of the People's Alliance party. Through these agreements new competences were transferred, with the reforms to many Statutes of Autonomy of the "slow-route" communities with the aim of equalizing them to the "fast route" communities.[16] In 1995, the cities of Ceuta and Melilla were constituted as "autonomous cities" without legislative powers, but with an autonomous assembly not subordinated to any other province or community.

The creation of the autonomous communities was a diverse process, that started with the constitution, was normalized with the autonomic pacts and was completed with the Statutes of Autonomy.[22] It is, however, an ongoing process; further devolution—or even the return of transferred competences—is always a possibility. This has been evidenced in the 2000s, at the beginning with a wave of approval of new Statutes of Autonomy for many communities, and more recently with many considering the recentralization of some competences in the wake of the economic and financial crisis of 2008. Nonetheless Spain is now a decentralized country with a structure unlike any other, similar but not equal to a federation,[22] even though in many respects the country can be compared to countries which are undeniably federal.[37] The unique resulting system is referred to as "Autonomous state", or more precisely "State of Autonomies".[15]

Current state of affairs

With the implementation of the Autonomous Communities, Spain went from being one of the most centralized countries in the OECD to being one of the most decentralized; in particular, it has been the country where the incomes and outcomes of the decentralized bodies (the Autonomous Communities) has grown the most, leading this rank in Europe by 2015 and being fifth among OECD countries in tax devolution (after Canada, Switzerland, the United States and Austria).[38][39] By means of the State of Autonomies implemented after the Spanish Constitution of 1978, Spain has been quoted to be "remarkable for the extent of the powers peacefully devolved over the past 30 years" and "an extraordinarily decentralized country", with the central government accounting for just 18% of public spending,[40] 38% by the regional governments, 13% by the local councils, and the remaining 31% by the social security system.[41]

In terms of personnel, by 2010 almost 1,350,000 people or 50.3% of the total civil servants in Spain were employed by the autonomous communities;[42] city and provincial councils accounted for 23.6% and those employees working for the central administration (police and military included) represented 22.2% of the total.[43]

Tensions within the system

Peripheral nationalism continues to play a key role in Spanish politics. Some peripheral nationalists view that there is a vanishing practical distinction between the terms "nationalities" and "regions",[44] as more competences are transferred to all communities in roughly the same degree and as other communities have chosen to identify themselves as "nationalities". In fact, it has been argued that the establishment of the State of Autonomies "has led to the creation of "new regional identities",[45][46] and "invented communities".[46]

Many in Galicia, the Basque Country, and Catalonia view their communities as "nations", not just "nationalities", and Spain as a "plurinational state" or a "nation of nations", and they have made demands for further devolution or secession.

In 2004 the Basque Parliament approved the Ibarretxe Plan, whereby the Basque Country would approve a new Statute of Autonomy containing key provisions such as shared sovereignty with Spain, full independence of the judiciary, and the right to self-determination, and assuming all competences except that of the Spanish nationality law, defense, and monetary policy. The plan was rejected by the Spanish Parliament in 2005 and the situation has remained largely stable in that front so far.

A particularly contentious point – especially in Catalonia – has been the one of fiscal tensions, with Catalan nationalists intensifying their demand for further financing during the 2010s. In this regard, the new rules for fiscal decentralisation in force since 2011 already make Spain one of the most decentralised countries in the world also in budgetary and fiscal matters,[47] with the base for income tax split at 50/50 between the Spanish government and the regions (something unheard of in much bigger federal states such as Germany or the United States, which retain the income tax as an exclusively or primarily federal one).[47] Besides, each region can also decide to set its own income tax bands and its own additional rates, higher or lower than the federal rates, with the corresponding income accruing to the region which no longer has to share it with other regions.[47] This current level of fiscal decentralisation has been regarded by economists such as Thomas Piketty as troublesome since, in his view, "challenges the very idea of solidarity within the country and comes down to playing the regions against each other, which is particularly problematic when the issue is one of income tax as this is supposed to enable the reduction of inequalities between the richest and the poorest, over and above regional or professional identities".[47]

Independence process in Catalonia

The severe economic crisis in Spain that started in 2008 produced different reactions in the different communities. On one hand, some began to consider a return of some responsibilities to the central government.[48] while, on the other hand, in Catalonia debate on the fiscal deficit—Catalonia being one of the largest net contributors in taxes— led many who are not necessarily separatist but who are enraged by the financial deficit to support secession.[49][50] In September 2012, Artur Mas, then Catalonia's president, requested from the central government a new "fiscal agreement", with the possibility of giving his community powers equal to those of the communities of chartered regime, but prime minister Mariano Rajoy refused. Mas dissolved the Catalan Parliament, called for new elections, and promised to conduct a referendum on independence within the next four years.[51]

Rajoy's government declared that they would use all "legal instruments"—current legislation requires the central executive government or the Congress of Deputies to call for or sanction a binding referendum—[52] to block any such attempt.[53] The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party and its counterpart in Catalonia proposed to reopen the debate on the territorial organization of Spain, changing the constitution to create a true federal system to "better reflect the singularities" of Catalonia, as well as to modify the current taxation system.[54]

On Friday 27 of October 2017 the Catalan Parliament voted the independence of Catalonia; the result was 70 in favor, 10 against, 2 neither, with 53 representatives not present in protest. In the following days, the members of the Catalan government either fled or were imprisoned.

One scholar summarises the current situation as follows:

the autonomous state appears to have come full circle, with reproaches from all sides. According to some, it has not gone far enough and has failed to satisfy their aspirations for improved self-government. For others it has gone too far, fostering inefficiency or reprehensible linguistic policies.[56]

Constitutional and statutory framework

The State of Autonomies, as established in Article 2 of the constitution, has been argued to be based on four principles: willingness to accede to autonomy, unity in diversity, autonomy but not sovereignty of the communities, and solidarity among them all.[57] The structure of the autonomous communities is determined both by the devolution allowed by the constitution and the competences assumed in their respective Statutes of Autonomy. While the autonomic agreements and other laws have allowed for an "equalization" of all communities, differences still remain.

The Statute of Autonomy

The Statute of Autonomy is the basic institutional law of the autonomous community or city, recognized by the Spanish constitution in article 147. It is approved by a parliamentary assembly representing the community, and then approved by the Cortes Generales, the Spanish Parliament, through an "Organic Law", requiring the favourable vote of the absolute majority of the Congress of Deputies.

For communities that acceded to autonomy through the "fast route", a referendum is required before it can be sanctioned by the Parliament. The Statutes of Autonomy must contain, at least, the name of the community, its territorial limits, the names, organization and seat of the institutions of government, the competences they assume and the principles for their bilingual policy, if applicable.

The constitution establishes that all competences not explicitly assumed by the state—the central government—in the constitution, can be assumed by the autonomous community in their Statutes of Autonomy; but also, all competences not explicitly assumed by the autonomous community in their Statutes of Autonomy are automatically assumed by the state.[27] In case of conflict, the constitution prevails.[27] In case of disagreement, any administration can bring the case before the Constitutional Court of Spain.

Institutional organization

All autonomous communities have a parliamentary system based on a division of powers comprising:

- A Legislative Assembly, whose members are elected by universal suffrage according to a system of proportional representation, in which all areas that integrate the territory are fairly represented

- A Council of Government, with executive and administrative powers, headed by a prime minister, whose official title is "president",[lower-alpha 5][lower-roman 6] elected by the Legislative Assembly—usually the leader of the party or coalition with a majority in the Assembly—and nominated by the King of Spain

- A High Court of Justice, hierarchically under the Supreme Court of Spain

The majority of the communities have approved regional electoral laws within the limits set up by the laws for the entire country. Despite minor differences, all communities use proportional representation following D'Hondt method; all members of regional parliaments are elected for four-year terms, but the president of the community has the faculty to dissolve the legislature and call for early elections. Nonetheless in all communities except for the Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia, and Andalusia elections are held the last Sunday of May every four years, concurrent with municipal elections in all Spain.[57]

The names of the Council of Government and the Legislative Assembly vary between communities. In some autonomous communities, these institutions are restored historical bodies of government or representation of the previous kingdoms or regional entities within the Spanish Crown—like the Generalitat of Catalonia—while others are entirely new creations.

In some, both the executive and the legislature, though constituting two separate institutions, are collectively identified with a single specific name. A specific denomination may not refer to the same branch of government in all communities; for example, junta may refer to the executive office in some communities, to the legislature in others, or to the collective name of all branches of government in others.

Given the ambiguity in the constitution that did not specify which territories were nationalities and which were regions, other territories, besides the implicit three "historical nationalities", have also chosen to identify themselves as nationalities, in accordance with their historical regional identity, such as Andalusia, Aragon, the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands, and the Valencian Community.

The two autonomous cities have more limited competences than autonomous communities, but more than other municipalities. The executive is exercised by a president, who is also the mayor of the city. In the same way, limited legislative power is vested in a local assembly in which the deputies are also the city councillors.

Legal powers

The autonomic agreements of 1982 and 1992 tried to equalize powers (competences) devolved to the 17 autonomous communities, within the limits of the constitution and the differences guaranteed by it. This has led to an "asymmetrical homogeneity".[22] In the words of the Constitutional Court of Spain in its ruling of August 5, 1983, the autonomous communities are characterized by their "homogeneity and diversity...equal in their subordination to the constitutional order, in the principles of their representation in the Senate, in their legitimation before the Constitutional Court, and in that the differences between the distinct Statutes [of Autonomy] cannot imply economic or social privileges; however, they can be unequal with respect to the process to accede to autonomy and the concrete determination of the autonomic content of their Statute, and therefore, in their scope of competences. The autonomic regime is characterized by an equilibrium between homogeneity and diversity ... Without the former there will be no unity or integration in the state's ensemble; without the latter, there would not be [a] true plurality and the capacity of self-government".[58]

The asymmetrical devolution is a unique characteristic of the territorial structure of Spain, in that the autonomous communities have a different range of devolved competences. These were based on what has been called in Spanish as hechos diferenciales, "differential facts" or "differential traits".[lower-roman 7][59]

This expression refers to the idea that some communities have particular traits, with respect to Spain as a whole. In practice these traits are a native "language proper to their own territories" separate from Spanish, a particular financial regime or special civil rights expressed in a code, which generate a distinct political personality.[59] These hechos diferenciales of their distinct political and historical personality are constitutionally and statutorily (i. e., in their Statutes of Autonomy) recognized in the exceptions granted to some of them and the additional competences they assume.[59]

Competences can be divided into three groups: exclusive to the central state or central government, shared competences, and devolved competences exclusive to the communities. Article 149 states which powers are exclusive to the central government: international relations, defense, administration of justice, commercial, criminal, civil, and labour legislation, customs, general finances and state debt, public health, basic legislation, and general coordination.[5] All autonomous communities have the power to manage their own finances in the way they see fit, and are responsible for the administration of education—school and universities—health and social services and cultural and urban development.[60] Yet there are differences as stipulated in their Statutes and the constitution:[57]

- Aragon, the Balearic Islands, the Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia and the Valencian Community have a regional civil code

- Basque Country, Catalonia, and Navarre have their own police corps—the Ertzaintza, the Mossos d'Esquadra and the Nafarroako Foruzaingoa, respectively; other communities have them too, but not fully developed (adscribed to the Spanish National Police)

- The Canary Islands have a special financial regime in virtue of its location as an overseas territories, while the Basque Country and Navarre have a distinct financial regime called "chartered regime"

- The Balearic Islands, the Basque Country, Catalonia, Galicia, Navarre, and the Valencian Community have a co-official language and therefore a distinct linguistic regime[57]

Degree of financial autonomy

How the communities are financed has been one of the most contentious aspects in their relationship with the central government.[45] The constitution gave all communities significant control over spending, but the central government retained effective control of their revenue supply.[45] That is, the central government is still charge of levying and collecting most taxes, which it then redistributes to the autonomous communities with the aim of producing "fiscal equalization".[5] This applies to all communities, with the exception of the Basque Country and Navarre.

This financial scheme is known as the "common regime". In essence, fiscal equalization implies that richer communities become net contributors to the system, while poorer communities become net recipients. The two largest net contributors to the system are the Balearic Islands and the Community of Madrid, in percentage terms, or the Community of Madrid and Catalonia in absolute terms.[5][61]

Central government funding is the main source of revenue for the communities of "common regime". Redistribution, or transfer payments, are given to the communities of common regime to manage the responsibilities they have assumed. The amount they receive is based upon several calculations which include a consideration for population, land area, administrative units, dispersal of population, relative poverty, fiscal pressure and insularity.[7] The central government is committed to returning a specific percentage of taxes to all communities with common regime, within the differences allowed for fiscal equalization. The communities of common regime have the ability to add a surcharge to the so-called "ceded taxes"—taxes set at the central level, but collected locally—and they can lower or raise personal income taxes up to a limit.[45]

The Basque Country and Navarre were granted an exception in the fiscal and financial system through the first additional disposition of the constitution that recognizes their historical "charters"[lower-roman 8] —hence they are known as "communities of chartered regime" or "foral regime".[45] Through their "chartered regime", these communities are allowed to levy and collect all so-called "contracted taxes", including income tax and corporate tax, and they have much more flexibility to lower or raise them.[45] This "chartered" or "foral" contract entails true financial autonomy.[45]

Since they collect almost all taxes, they send to the central government a pre-arranged amount known as cupo, "quota" or aportación, "contribution", and the treaty whereby this system is recognized is known as concierto, "treaty", or convenio, "pact".[62] Hence they are also said to have concierto económico, an "economic treaty". Since they collect all taxes themselves and only send a prearranged amount to the central government for the competences exclusive to the state, they do not participate in "fiscal equalization", in that they do not receive any money back.

Spending

As more responsibilities have been assumed by the autonomous communities in areas such as social welfare, health, and education, public expenditure patterns have seen a shift from the central government towards the communities since the 1980s.[45] In the late 2000s, autonomous communities accounted for 35% of all public expenditure in Spain, a percentage that is even higher than that of states within a federation.[5] With no legal constraints to balance budgets, and since the central government retains control over fiscal revenue in the communities of common regime, these are in a way encouraged to build up debt.[45]

The Council on Fiscal and Financial Policy, which includes representatives of the central government and of the autonomous communities, has become one of the most efficient institutions of coordination in matters of public expenditures and revenue.[63] Through the Council several agreements of financing have been agreed, as well as limits to the communities' public debt. The Organic Law of the Financing of Autonomous Communities of 1988 requires that the communities obtain the authorization of the central Ministry of Finance to issue public debt.[63]

Linguistic regimes

The preamble to the constitution explicitly stated that it is the nation's will to protect "all Spaniards and the peoples of Spain in the exercise of human rights, their cultures and traditions, languages and institutions".[64] This is a significant recognition not only in that it differed drastically from the restrictive linguistic policies during the Franco era, but also because part of the distinctiveness of the "historical nationalities" lies on their own regional languages.[8][9] The nation is thus openly multilingual,[11] in which Castilian—that is, Spanish—is the official language in all territories, but the "other Spanish languages" can also be official in their respective communities, in accordance with their Statutes of Autonomy.

Article 3 of the constitution ends up declaring that the "richness of the distinct linguistic modalities of Spain represents a patrimony which will be the object of special respect and protection".[65] Spanish remains the only official language of the state; other languages are only co-official with Spanish in the communities that have so regulated. In addition, knowledge of the Spanish language was declared a right and an obligation of all Spaniards.

Spanish legislation, most notably in the Statutes of Autonomy of the bilingual communities, use the term "own language", or "language proper to a community",[lower-roman 9] to refer to a language other than Spanish that originated or had historical roots in that particular territory. The Statutes of Autonomy of the respective autonomous communities have declared Basque the language proper to the Basque Country and Navarre, Catalan the language proper to Catalonia, the Balearic Islands and the Valencian Community—where it is historically, traditionally and officially known as Valencian—and Galician to be the language proper to Galicia. There are other protected regional languages in other autonomous communities. As a percentage of total population in Spain, Basque is spoken by 2%, Catalan/Valencian by 17%, and Galician by 7% of all Spaniards.[66] A 2016 Basque Government census revealed 700,000 fluent speakers in Spain (51,000 in Basque counties in France) and 1,185.000 total when passive speakers are included.[67]

| Language | Status | Speakers in Spain[lower-alpha 6] |

|---|---|---|

| Aragonese | Not official but recognised in Aragon | 11,000[68] |

| Asturleonese | Not official but recognised in Asturias and in Castile and León[lower-alpha 7] | 100,000[69] |

| Basque | Official in the Basque Country and Navarre | 580,000[70] |

| Catalan/Valencian | as Catalan, official in Catalonia and Balearic Islands, and as Valencian, in the Valencian Community;[lower-alpha 8] Not official but recognised in Aragon | around 10 million,[71] including 2nd language speakers |

| Galician | Official in Galicia | 2.34 million[72] |

| Occitan | Official in Catalonia | 4,700 |

| Fala | Not official but recognised as a "Bien de Interés Cultural" in Extremadura[73] | 11,000 |

Subdivisions

The Spanish constitution recognizes the municipalities[lower-roman 10] and guarantees their autonomy. Municipal, or city, councils[lower-roman 11] are in charge of the municipalities' government and administration, and they are integrated by a mayor[lower-roman 12] and councillors,[lower-roman 13] the latter elected by universal suffrage, and the former elected either by the councillor or by suffrage.

Provinces[lower-roman 14] are groups of municipalities and recognized by the constitution. Their competences and institutions of government vary greatly among communities. In all communities which have more than one province, provinces are governed by "provincial deputations" or "provincial councils",[lower-roman 15] with a limited scope of administrative competences.[45]

In the Basque Country, the provinces, renamed as "historical territories",[lower-roman 4] are governed by "chartered deputations"[lower-roman 16]—with assume the competences of a provincial deputation as well as the fiscal powers of their "chartered regime"—and by "General Juntas" [lower-roman 17]—parliaments with legislative powers.[45]

In the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands, each major island is governed by an "insular council".[lower-roman 18] In Catalonia, the "provincial deputations" have very little power, as other territorial subdivisions have been created.[45]

In those seven autonomous communities formed by a single province, the provincial deputations have been replaced by the communities' institutions of government; in fact, the provinces themselves are not only coterminous with the communities, but correspond in essence to the communities themselves. The two-tier territorial organization common to most communities—first province, then municipalities—is therefore non-existent in these "uniprovincial" communities.[5]

| Autonomous community | Provinces[lower-alpha 9] |

|---|---|

| Andalusia | Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba,[lower-alpha 10] Granada, Huelva, Jaén, Málaga and Seville |

| Aragon | Huesca, Teruel and Zaragoza[lower-alpha 11] |

| Principality of Asturias | (Asturias)[lower-alpha 12] |

| Balearic Islands | (Balearic Islands) |

| Basque Country | Álava, Biscay, and Gipuzkoa[lower-alpha 9] |

| Canary Islands | Las Palmas and Santa Cruz de Tenerife |

| Cantabria | (Cantabria)[lower-alpha 13] |

| Castilla-La Mancha | Albacete, Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Guadalajara and Toledo |

| Castile and León | Ávila, Burgos, León, Palencia, Salamanca, Segovia, Soria, Valladolid and Zamora |

| Catalonia | Barcelona, Girona, Lleida and Tarragona |

| Extremadura | Badajoz and Cáceres |

| Galicia | A Coruña, Lugo, Ourense and Pontevedra |

| La Rioja | (La Rioja)[lower-alpha 14] |

| Madrid | (Madrid) |

| Murcia | (Murcia) |

| Navarre | (Navarre)[lower-alpha 15] |

| Valencian Community | Alicante, Castellón and Valencia |

The constitution also allows the creation of other territorial entities formed by groups of municipalities. One of such territorial subdivision is the comarca (equivalent of a "district", "shire", or "county"). While all communities have unofficial historical, cultural, or natural comarcas,[lower-roman 19] only in Aragon and Catalonia, they have been legally recognized as territorial entities with administrative powers (see comarcal councils).[lower-roman 20]

Competences of the autonomous governments

The competences of the autonomous communities are not homogeneous.[74] Broadly the competences are divided into "Exclusive", "Shared", and "Executive" ("partial"). In some cases, the autonomous community may have exclusive responsibility for the administration of a policy area but may only have executive (i. e., carries out) powers as far as the policy itself is concerned, meaning it must enforce policy and laws decided at the national level.

| Basque Country | Galicia | Catalonia | Others | |

| Law, Order & Justice | ||||

| Police | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Public Safety (Civil protection, Firearms, gambling) | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Civil & Administrative Law (Justice, Registries, Judicial Appointments) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Child & Family Protection | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Consumer Protection | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Data protection | Shared | Shared | Shared | |

| Civil registry & Statistics | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Health, Welfare & Social Policy | Basque Country | Galicia | Catalonia | Others |

| Social Welfare | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Equality | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | AN (Exclusive) |

| Social Security | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Employment | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Health Care | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Benevolent/Mutual Societies | Administrative | Administrative | Shared | AN, NA, VC (Shared) |

| Economy, Transport & Environment | Basque Country | Galicia | Catalonia | Others |

| Public Infrastructure (Road, Highways) | Exclusive | Shared | Shared | |

| Public Infrastructure (Rail, Airports) | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Environment (Nature, Contamination, Rivers, Weather) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Shared | Shared |

| Economic Planning & Development | Exclusive | Exclusive | Shared | |

| Advertising, Regional Markets and regional controlled origin designations | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Professional associations | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Workplace & Industrial safety | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Financial (Regional Cooperative Banks, & Financial Markets) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Shared | Exclusive |

| Press & Media | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Water (Local drainage Basin) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Regional Development (Coast, Housing Rural Services) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Public Sector & Cooperative Banks | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Energy & Mining | Exclusive | Exclusive | Shared | Shared |

| Competition | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial |

| Agriculture and Animal welfare | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Fisheries | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Hunting & Fishing | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | |

| Local Transport & Communications (Road Transport, Maritime Rescue) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Tourism | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Culture & Education | Basque Country | Galicia | Catalonia | Others |

| Culture (libraries, museums, Film industry, Arts, & Crafts...) | Shared | Shared | Shared | Shared |

| Culture (Language Promotion, R & D Projects) | Shared | Shared | Exclusive | Shared |

| Culture (Sports, Leisure, Events) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Education (Primary, secondary, University, Professional & Language) | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| Religious Organizations | Shared | Exclusive | ||

| Cultural, Welfare, & Education Associations Regulation | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive | Exclusive |

| International Relations (Culture & language, Cross Border relations) | Partial | Partial | Partial | |

| Resources & Spending | Basque Country | Galicia | Catalonia | Others |

| Own Tax resources | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Allocation by Central Government | No | Convergence Funds | Convergence Funds | Convergence Funds (except NA) |

| Other resources | Co-payments (Health & Education) | Co-payments (Health & Education) | Co-payments (Health & Education) | Co-payments (Health & Education) |

| Resources | 100% | 60% | 60% | 60% |

| Devolved Spending as % of total public spending | 36% (Average for all autonomous communities)[75] | |||

See also

Notes

- Spanish pronunciation: [komuniˈðað awˈtonoma]

- Basque pronunciation: [autonomia erkiðeɣo]

- Catalan pronunciation: [kumuniˈtat əwˈtɔnumə]

- Galician pronunciation: [komuniˈðaðɪ awˈtɔnʊmɐ]

- In the Basque Country, the head of government is officially known as lehendakari in Basque, or by the Spanish rendering of the title, lendakari.

- All figures as reported on Ethnologue for the number of speakers in Spain only.

- In the Statute of Autonomy of Castile and León, the Astur-Leonese dialect spoken therein is referred to as Leonese.

- The Catalan dialect spoken in the Valencian Community is historically, traditionally and officially referred to as Valencian.

- The Basque provinces and Navarre are officially known as "historical territories" or "chartered territories".[lower-roman 4]

- Also spelled "Cordova" in English.

- Also spelled "Saragossa" in English.

- Previously known as Oviedo.

- Previously known as Santander.

- Previously known as Logroño.

- Previously known as Pamplona.

- Translation of terms

- "Autonomies" (in Spanish: autonomías, in Basque: autonomien, in Catalan/Valencian: autonomies, in Galician: autonomías).

- "State of Autonomies" (in Spanish: Estado de las Autonomías, in Basque: Autonomien Estatuaren, in Catalan/Valencian: Estat de les Autonomies, in Galician: Estado das Autonomías). Also known as "Autonomous State"[6] (in Spanish: Estado Autonómico, in Basque: Autonomia Estatuko, or Estatuaren, in Catalan/Valencian: Estat Autonòmic, in Galician: Estado Autonómico)

- "Statutes of Autonomy" (in Spanish: Estatutos de Autonomía, in Basque: Autonomia Estatutuen, in Catalan/Valencian: Estatuts d'Autonomia, in Galician: Estatutos de Autonomía).

- "Historical territories" or "chartered territories" (in Spanish: territorios históricos or territorios forales, in Basque: lurralde historikoak or foru lurraldeak).

- "Autonomic pacts" or "autonomic agreements" (in Spanish: pactos autonómicos or acuerdos autonómicos).

- "Autonomic president", "regional president", or simply "president" (in Spanish: presidente autonómico, presidente regional, or simply presidente; in Catalan/Valencian: president autonòmic, president regional, or simply president; in Galician: presidente autonómico, presidente rexional, or simply presidente). In the Basque language lehendakari is not translated.

- "Differential facts", or, "traits" (in Spanish: hechos diferenciales, in Basque: eragin diferentziala, in Catalan/Valencian: fets diferencials, in Galician: feitos diferenciais).

- "Charters" (in Spanish: fueros, in Basque: foruak).

- "Own language (of a community)" or "language proper [to a community]" (in Spanish: lengua propia, in Basque: berezko hizkuntza, in Catalan/Valencian: llengua pròpia, in Galician: lingua propia).

- "Municipalities" (in Spanish: municipios, in Basque: udalerriak, in Catalan/Valencian: municipis, in Galician: concellos or municipios).

- "City councils" or "municipal councils" (in Spanish: ayuntamientos, in Basque: udalak, in Catalan/Valencian: ajuntaments, in Galician: concellos).

- "Mayor" (in Spanish: alcalde, in Basque: alkatea, in Catalan/Valencian: alcalde or batlle / batle, in Galician: alcalde).

- "Councillors" (in Spanish: concejales, in Basque: zinegotziak, in Catalan/Valencian: regidors, in Galician: concelleiros).

- "Provinces" (in Spanish: provincias, in Basque: probintziak, in Catalan/Valencian: províncies, in Galician: provincias).

- "Provincial deputations" or "provincial councils" (in Spanish: diputaciones provinciales, in Catalan/Valencian: diputacions provincials, in Galician: deputacións provinciais).

- "Chartered deputations" (in Spanish: diputaciones forales, in Basque: foru aldundiek).

- "General Juntas" (in Spanish: Juntas Generales, in Basque: Biltzar Nagusiak).

- "Insular council" (in Spanish: consejo insular or cabildo insular, in Catalan: consell insular).

- "Comarcas" (in Spanish: comarcas, in Basque: eskualdeak, in Catalan/Valencian: comarques, in Galician: comarcas or bisbarras).

- "Comarcal councils" (in Spanish: consejos comarcales, in Catalan/Valencian: consells comarcals).

References

- "Organización territorial. El Estado de las Autonomías" (PDF). Recursos Educativos. Instituto Nacional de Tecnologías Educativas y de Formación del Profesorado. Ministerio de Eduación, Cultura y Deporte. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- Article 2. Cortes Generales (Spanish Parliament) (1978). "Título Preliminar". Spanish Constitution of 1978. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Article 143. Cortes Generales (Spanish Parliament) (1978). "Título VIII. De la Organización Territorial del Estado". Spanish Constitution of 1978. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Bacigalupo Sagesse, Mariano (June 2005). "Sinópsis artículo 145". Constitución española (con sinópsis). Congress of the Deputies. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Ruíz-Huerta Carbonell, Jesús; Herrero Alcalde, Ana (2008). Bosch, Núria; Durán, José María (eds.). Fiscal Equalization in Spain. Fiscal Federalism and Political Decentralization: Lessons from Spain, Germany and Canada. Edward Elgar Publisher Limited. ISBN 9781847204677. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- The Federal Option and Constitutional Management of Diversity in Spain Xavier Arbós Marín, page 375; included in 'The Ways of Federalism in Western Countries and the Horizons of Territorial Autonomy in Spain' (volume 2), edited by Alberto López-Eguren and Leire Escajedo San Epifanio; edited by Springer ISBN 978-3-642-27716-0, ISBN 978-3-642-27717-7(eBook)

- Börzel, Tanja A (2002). States and Regions in the European Union. University Press, Cambridge. pp. 93–151. ISBN 978-0521008600. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- Villar, Fernando P. (June 1998). "Nationalism in Spain: Is It a Danger to National Integrity?". Storming Media, Pentagon Reports. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- Shabad, Goldie; Gunther, Richard (July 1982). "Language, Nationalism and Political Conflict in Spain". Comparative Politics. Comparative Politics Vol 14 No. 4. 14 (4): 443–477. doi:10.2307/421632. JSTOR 421632.

- Moreno Hernández, Luis Manuel. "Federalization in Multinational Spain" (PDF). Unidad de Políticas Comparadas. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

- Conversi, Daniele (2002). "The Smooth Transition: Spain's 1978 Constitution and the Nationalities Question" (PDF). National Identities, Vol 4, No. 3. Carfax Publishing, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- Moreno Fernández, Luis Miguel (2008) [April 1997]. La federalización de España. Poder político y territorio (2nd ed.). Siglo XXI España Editores. pp. 98, 99. ISBN 978-8432312939.

- Schrijver, Frans (30 June 2006). Regionalism after Regionalisation. Spain, France and the United Kingdom. Vossiupers UvA. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 978-9056294281. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- Moreno Fernández, Luis Miguel (2008) [April 1997]. La federalización de España. Poder político y territorio (2nd ed.). Siglo XXI España Editores. pp. 78, 79. ISBN 978-8432312939.

- Colomer, Josep M. (1 October 1998). "The Spanish 'state of autonomies': non-institutional federalism.(Special Issue on Politics and Policy in Democratic Spain: No Longer Different?)". West European Politics. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- Aparicio, Sonia. "Café para Todos". La España de las Autonomías. Un Especial de elmundo.es. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Portero Molina, José Antonio (2005). Vidal Beltrán, José María; García Herrera, Miguel Ángel (eds.). El Estado de las Autonomías en Tiempo de Reformas. El Estado Autonómico: Integración, Solidaridad, Diversidad, Volumen 1. Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública. pp. 39–64. ISBN 978-8478799770. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Delgado-Ibarren García-Campero, Manuel (June 2005). "Sinópsis artículo 2". Constitución española (con sinópsis). Congress of the Deputies. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Why Talk of Federalism Won't Help Peace in Syria|Foreign Policy

- "Devolution of Powers in Spain" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-12. Retrieved 2016-03-31.

- Devolution and Democracy: Identity, Preferences, and Voting in the Spanish “State of Autonomies”

- Pérez Royo, Javier (December 1999). Hernández Lafuente, Adolfo (ed.). Desarrollo y Evolución del Estado Autonómico: El Proceso Constituyente y el Consenso Constitucional. El Funcionamiento del Estado Autonómico. Ministerio de Administraciones Públicas. pp. 50–67. ISBN 978-8470886904. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- Núñez Seixas, Xosé M (2000). Álvarez Junco, José; Schubert, Adrian (eds.). The awakening of peripheral nationalisms and the State of the Autonomous Communities. Spanish History since 1808. Arnold Publishers. pp. 315–330. ISBN 978-0340662298. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- Clavero Arévalo, Manuel (2006). "Un balance del Estado de las Autonomías" (PDF). Colección Mediterráneo Económico, num. 10. Fundación Caja Rural Intermediterránea. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- Barbería, José Luis (30 September 2012). "¿Reformamos la Constitución?". El País. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- Alonso de Antonio, José Antonio (June 2003). "Sinópsis artículo 143". Constitución española (con sinópsis). Congress of the Deputies. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- Congreso de los Diputados (1978). "Título VIII. De la Organización Territorial del Estado. Capítulo tercero. De las Comunidades Autónomas. Artículos 143 a 158". Constitución española. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Alonso de Antonio, José Antonio (December 2003). "Sinópsis Disposición Transitoria 2". Congress of Deputies. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- González García, Ignacio. "La Prohibición de la Federación entre Territorios Autónomos en el Constitucionalismo Español" (PDF). Congreso Iberoamericano de Derecho Constitucional. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- Congreso de los Diputados (1978). "Disposiciones transitorias". Constitución española. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Congreso de los Diputados (1978). "Disposiciones transitorias". Constitución española. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- Rebollo, Luis Martín (2005). Ministerio de Justicia (ed.). Consideraciones sobre la Reforma de los Estatutos de Autonomía de las Comunidades Autónomas. La Reforma Constitucional: XXVI Jornadas de Estudio (27, 28 y 29 de octubre de 2004). Dirección del Servicio Jurídico del Estado. ISBN 978-84-7787-815-5. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "El referéndum de iniciativa, barrera no exigida a las nacionalidades históricas". El País (in Spanish). 9 December 1979. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- "Acuerdos Autonómicos firmados por el Gobierno de la Nación y el Partido Socialista Obrero Español el 31 de julio de 1981" (PDF). 31 July 1981. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- García Ruíz, José Luis (2006). García Ruíz, José Luis; Girón Reguera, Emilia (eds.). Dos siglos de cuestión territorial: de la España liberal al Estado de las autonomías. Estudios sobre descentralización territorial. El caso particular de Colombia. Servicio de Publicaciones. Universidad de Cádiz. pp. 109–126. ISBN 978-8498280371. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- Moreno Fernández, Luis Miguel (2008) [April 1997]. La federalización de España. Poder político y territorio (2nd ed.). Siglo XXI España Editores. p. 66. ISBN 978-8432312939.

- The Federal Option and Constitutional Management of Diversity in Spain Xavier Arbós Marín, page 381; included in 'The Ways of Federalism in Western Countries and the Horizons of Territorial Autonomy in Spain' (volume 2), edited by Alberto López-Eguren and Leire Escajedo San Epifanio; edited by Springer ISBN 978-3-642-27716-0, ISBN 978-3-642-27717-7(eBook)

- Ramon Marimon (23 March 2017). "Cataluña: Por una descentralización creíble". El País. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Fiscal Federalism 2016: Making Decentralization Work. OCDE.

- Mallet, Victor (18 August 2010). "Flimsier footings". Financial Times. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2010.(registration required)

- "A survey of Spain: How much is enough?". The Economist. 6 November 2008. Archived from the original on September 10, 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2010.(subscription required)

- Archived September 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- País, Ediciones El (2011-07-30). "Que al funcionario le cunda más | Edición impresa | EL PAÍS". El País. Elpais.com. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- Keatings, Michael (2007). "Federalism and the Balance of power in European States" (PDF). Support for Improvement in Governance and Management. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Inc. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Smith, Andy; Heywood, Paul (August 2000). "Regional Government in France and Spain" (PDF). University College London. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- Junco, José Álvarez (3 October 2012). "El sueño ilustrado y el Estado-nación". El País. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Piketty, Thomas (2017-11-14). "The Catalan Syndrom". lemonde.fr. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

- "Varias autonomías meditan devolver competencias por el bloqueo del gobierno". ABC. 29 July 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- "Catalonia: Europe's next state. A row about money and sovereignty". The Economist. 22 September 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Tremlett, Giles; Roberts, Martin (28 September 2012). "Spain's cultural fabric tearing apart as austerity takes its toll". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Two thirds of the Catalan Parliament approve organising a self-determination citizen vote within the next 4 years". Catalan News Agency. 28 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 October 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Ley Orgánica 2/1980, de 18 de enero, sobre Regulación de las Distintas Modalidades de Referéndum". Congress of the Deputies, Spain. 18 January 1980. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "Spain heads towards confrontation with Catalan parliament". The Guardian. 27 September 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- Calvo, Vera Gutiérrez; País, El (24 September 2012). "Rubalcaba, a favor de cambiar la Constitución para ir a un Estado federal". El País. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- The Federal Option and Constitutional Management of Diversity in Spain, Xavier Arbós Marín, page 395; included in 'The Ways of Federalism in Western Countries and the Horizons of Territorial Autonomy in Spain' (volume 2), edited by Alberto López-Eguren and Leire Escajedo San Epifanio; published by Springer ISBN 978-3-642-27716-0, ISBN 978-3-642-27717-7(eBook)

- de Carreras Serra, Francesc (2005). El Estado de las Autonomías en España. Descentralización en Perspectiva Comparada: España, Colombia y Brasil. Plural Editores. ISBN 978-9990563573. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- Castelao, Julio (June 2005). "Sinópsis artículo 137". Constitución española (con sinópsis). Congress of the Deputies. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- Aja, Eliseo (2003). "El Estado Autonómico de España a los 25 años de su constitución" (PDF). Congreso Ibeoramericano de Derecho Constitucional. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- "How much is enough? Devolution has been good for Spain, but it may have gone too far". The Economist. 6 November 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2012.(subscription required)

- "Madrid aporta al Estado más del doble que Cataluña". Cinco Días. 29 November 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Ministerio de Hacienda y Administraciones Públicas (Ministry of the Treasury and Public Administrations). "Régimen foral". Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- Toboso, Fernando (1 April 2001). "Un Primer Análisis Cuantitativo de la Organización Territorial de las Tareas de Gobierno en España, Alemania y Suiza". El Trimestre Económico. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2012. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required)

- Preamble to the Constitution. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- Third article. Cortes Generales (27 December 1978). "Spanish Constitution". Tribunal Constitucional de España. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2012.

- "Spain". The CIA World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- VI Enquete Euskal Herria 2016, in French

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Aragonese". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Asturian". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Basque". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Catalan". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- Lewis, M. Paul, ed. (2009). "Galician". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Sixteenth Edition. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "BOE.es - Documento BOE-A-2001-7994".

- "Estatutos de Autonomía comparados por materias". Secretaría de Estado de Administraciones Públicas (in Spanish). Ministerio de Hacienda y Administraciones Públicas. Gobierno de España. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "EL MODELO DE FINANCIACIÓN DE LAS COMUNIDADES AUTÓNOMAS DE RÉGIMEN COMÚN. Liquidación definitiva 2009". Ministerio de Política Territorial y Administración Pública (in Spanish). November 2011. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)