Lignan

The lignans are a large group of low molecular weight polyphenols found in plants, particularly seeds, whole grains, and vegetables.[1] The name derives from the Latin word for "wood".[2] Lignans are precursors to phytoestrogens.[1][3] They may play a role as antifeedants in the defense of seeds and plants against herbivores.[4]

Biosynthesis and metabolism

- Structures of some lignans

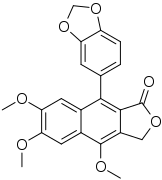

Matairesinol, illustrating the debenzylbutyrolactone motif

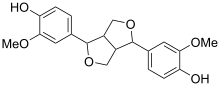

Matairesinol, illustrating the debenzylbutyrolactone motif Secoisolariciresinol, illustrating the 9,9'-dihydroxydibenzylbutane motif

Secoisolariciresinol, illustrating the 9,9'-dihydroxydibenzylbutane motif Justicidin A, illustrating the arylnaphthalene mofif

Justicidin A, illustrating the arylnaphthalene mofif Pinoresinol, illustrating the furanofuran motif

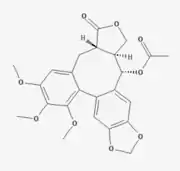

Pinoresinol, illustrating the furanofuran motif Steganacin, illustrating the dibenzocyclooctadienelactone motif

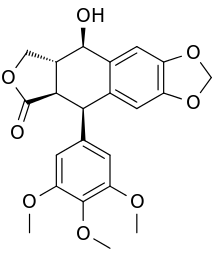

Steganacin, illustrating the dibenzocyclooctadienelactone motif Podophyllotoxin, illustrating the aryltetralin motif

Podophyllotoxin, illustrating the aryltetralin motif

Lignans and lignin differ in their molecular weight, the former being small and soluble in water, the latter being high polymers that are indigestable. Both are polyphenolic substances derived by oxidative coupling of monolignols. Thus, most lignans feature a C18 cores, resulting from the dimerization of C9 precursors. The coupling of the lignols occurs at C8. Eight classes of lignans are: "furofuran, furan, dibenzylbutane, dibenzylbutyrolactone, aryltetralin, arylnaphthalene, dibenzocyclooctadiene, and dibenzylbutyrolactol."[5]

Many lignans are metabolized by mammalian gut microflora, producing so-called enterolignans.[6][7]

Food sources

Flax seed and sesame seed contain higher levels of lignans than most other foods.[8] The principal lignan precursor found in flaxseed is secoisolariciresinol diglucoside.[8] Other sources of lignans include cereals (rye, wheat, oat and barley – rye being the richest source), soybeans, cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli and cabbage, and some fruit, particularly apricots and strawberries.[1]

Secoisolariciresinol and matairesinol were the first plant lignans identified in foods. Typically, lariciresinol and pinoresinol contribute about 75% to the total lignan intake whereas secoisolariciresinol and matairesinol contribute only about 25%.[1] Lignans are some of the secondary metabolites present in Cannabis sativa.[9]

Foods containing lignans:[1][10]

| Source | Amount per 100 g |

|---|---|

| Flaxseed | 300,000 μg (0.3 g) |

| Sesame seed | 29,000 μg (29 mg) |

| Brassica vegetables | 185–2321 μg |

| Grains | 7–764 μg |

| Red wine | 91 μg |

A 2007 study[11] shows the complexity of mammalian lignan precursors in the diet. In the table below are a few examples of the 22 analyzed species and the 24 lignans identified in this study.

Mammalian lignan precursors as aglycones (μg/100 g). Major compound(s) in bold.

| Foodstuff | Pinoresinol | Syringaresinol | Sesamin | Lariciresinol | Secoisolariciresinol | Matairesinol | Hydroxymatairesinol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flaxseed | 871 | 48 | not detected | 1780 | 165759 | 529 | 35 |

| Sesame seed | 47136 | 205 | 62724 | 13060 | 240 | 1137 | 7209 |

| Rye bran | 1547 | 3540 | not detected | 1503 | 462 | 729 | 1017 |

| Wheat bran | 138 | 882 | not detected | 672 | 868 | 410 | 2787 |

| Oat bran | 567 | 297 | not detected | 766 | 90 | 440 | 712 |

| Barley bran | 71 | 140 | not detected | 133 | 42 | 42 | 541 |

See also

References

- "Lignans". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- From lign- (Latin, "wood") + -an (chemical suffix).

- Korkina, L; Kostyuk, V; De Luca, C; Pastore, S (2011). "Plant phenylpropanoids as emerging anti-inflammatory agents". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 11 (10): 823–35. doi:10.2174/138955711796575489. PMID 21762105.

- Saleem, Muhammad; Kim, Hyoung Ja; Ali, Muhammad Shaiq; Lee, Yong Sup (2005). "An update on bioactive plant lignans". Natural Product Reports. 22 (6): 696–716. doi:10.1039/B514045P. PMID 16311631.

- Umezawa, Toshiaki (2003). "Diversity in lignan biosynthesis". Phytochemistry Reviews. 2 (3): 371–90. doi:10.1023/B:PHYT.0000045487.02836.32. S2CID 6276953.

- Adlercreutz, Herman (2007). "Lignans and Human Health". Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 44 (5–6): 483–525. doi:10.1080/10408360701612942. PMID 17943494. S2CID 31753060.

- Heinonen, S; Nurmi, T; Liukkonen, K; Poutanen, K; Wähälä, K; Deyama, T; Nishibe, S; Adlercreutz, H (2001). "In vitro metabolism of plant lignans: New precursors of mammalian lignans enterolactone and enterodiol". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 49 (7): 3178–86. doi:10.1021/jf010038a. PMID 11453749.

- Landete, José (2012). "Plant and mammalian lignans: A review of source, intake, metabolism, intestinal bacteria and health". Food Research International. 46 (1): 410–24. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2011.12.023.

- Flores-Sanchez, Isvett Josefina; Verpoorte, Robert (2008-10-01). "Secondary metabolism in cannabis". Phytochemistry Reviews. 7 (3): 615–39. doi:10.1007/s11101-008-9094-4. ISSN 1568-7767. S2CID 3353788.

- Milder IE, Arts IC, van de Putte B, Venema DP, Hollman PC (2005). "Lignan contents of Dutch plant foods: a database including lariciresinol, pinoresinol, secoisolariciresinol and matairesinol". British Journal of Nutrition. 93 (3): 393–402. doi:10.1079/BJN20051371. PMID 15877880.

- Smeds AI; Eklund, Patrik C.; Sjöholm, Rainer E.; Willför, Stefan M.; Nishibe, Sansei; Deyama, Takeshi; Holmbom, Bjarne R.; et al. (2007). "Quantification of a Broad Spectrum of Lignans in Cereals, Oilseeds, and Nuts". J. Agric. Food Chem. 55 (4): 1337–46. doi:10.1021/jf0629134. PMID 17261017.