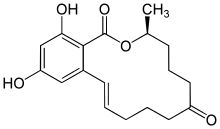

Zearalenone

Zearalenone (ZEN), also known as RAL and F-2 mycotoxin, is a potent estrogenic metabolite produced by some Fusarium and Gibberella species.[1] Particularly, is produced by Fusarium graminearum, Fusarium culmorum, Fusarium cerealis, Fusarium equiseti, Fusarium verticillioides, and Fusarium incarnatum.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(3S,11E)-14,16-Dihydroxy-3-methyl-3,4,5,6,9,10-hexahydro-1H-2-benzoxacyclotetradecine-1,7(8H)-dione | |

| Other names

Mycotoxin F2 | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.038.043 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C18H22O5 | |

| Molar mass | 318.369 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Several Fusarium species produce toxic substances of considerable concern to livestock and poultry producers, namely deoxynivalenol, T-2 toxin, HT-2 toxin, diacetoxyscirpenol (DAS) and zearalenone. Zearalenone is the primary toxin, causing infertility, abortion or other breeding problems, especially in swine.

Zearalenone is heat-stable and is found worldwide in a number of cereal crops, such as maize, barley, oats, wheat, rice, and sorghum.[2][3]

In addition to its actions on the classical estrogen receptors, zearalenone has been found to act as an agonist of the GPER (GPR30).[4]

Chemical and physical properties

Zearalenone is a white crystalline solid. It exhibits blue-green fluorescence when excited by long wavelength ultraviolet (UV) light (360 nm) and a more intense green fluorescence when excited with short wavelength UV light (260 nm). In methanol, UV absorption maxima occur at 236 (e = 29,700), 274 (e = 13,909) and 316 nm (e = 6,020). Maximum fluorescence in ethanol occurs with irradiation at 314 nm and with emission at 450 nm. Solubility in water is about 0.002 g/100 mL. It is slightly soluble in hexane and progressively more so in benzene, acetonitrile, methylene chloride, methanol, ethanol, and acetone. It is also soluble in aqueous alkali.

The naturally occurring isomer trans-zearalenone (trans-ZEN) is transformed by ultraviolet irradiation to cis-zearalenone (cis-ZEN).[5]

Dermal exposure

Zearalenone can permeate through the human skin.[6] However, no significant hormonal effects are expected after dermal contact in normal agricultural or residential environments.

Reproduction

The human and livestock exposure to ZEN through the diet poses health concern due to the onset of several sexual disorders and alterations in the development of sexual apparatus.[7][8] There are reliable case reports of early puberty in girls chronically exposed to ZEN in various regions of the world.[9]

Sampling and analysis

In common with other mycotoxins, sampling food commodities for zearalenone must be carried out to obtain samples representative of the consignment under test. Commonly used extraction solvents are aqueous mixtures of methanol, acetonitrile, or ethyl acetate followed by a range of different clean-up procedures that depend in part on the food and on the detection method in use. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) methods and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are commonly used. HPLC alone is not sufficient, as it may often yield false positive results. Today, HPLC-MS/MS analysis is used to quantify and confirm the presence of zearalenone.

The TLC method for zearalenone is: normal phase silica gel plates, the eluent: 90% dichloromethane, 10% v/v acetone; or reverse phase C18 silica plates; the eluent: 90% v/v methanol, 10% water. Zearalenone gives unmistakable blue luminiscence under UV.[1]

See also

- α-Zearalenol

- β-Zearalenol

- Taleranol

- Zeranol

- Zearalanone

References

- "Zearalenone". Fermentek.

- Kuiper-Goodman, T.; Scott, P. M.; Watanabe, H. (1987). "Risk Assessment of the Mycotoxin Zearalenone". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 7 (3): 253–306. doi:10.1016/0273-2300(87)90037-7. PMID 2961013.

- Tanaka, T.; Hasegawa, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Lee, U. S.; Sugiura, Y.; Ueno, Y. (1988). "Worldwide Contamination of Cereals by the Fusarium Mycotoxins Nivalenol, Deoxynivalenol, and Zearalenone. 1. Survey of 19 Countries". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. American Chemical Society. 36 (5): 979–983. doi:10.1021/jf00083a019.

- Prossnitz, Eric R.; Barton, Matthias (2014). "Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 389 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. ISSN 0303-7207. PMC 4040308. PMID 24530924.

- Brezina U, Kersten S, Valenta H, et al. (2013). "UV-induced cis-trans isomerization of zearalenone in contaminated maize". Mycotoxin Res. 29: 221. doi:10.1007/s12550-013-0178-7.

- Boonen, J.; Malysheva, S. V.; Taevernier, L.; Diana di Mavungu, J.; de Saeger, S.; de Spiegeleer, B. (2012). "Human Skin Penetration of Selected Model Mycotoxins". Toxicology. 301 (1–3): 21–32. doi:10.1016/j.tox.2012.06.012. PMID 22749975.

- Massart, F.; Saggese, G. (April 2010). "Oestrogenic mycotoxin exposures and precocious pubertal development". International Journal of Andrology. 33 (2): 369–376. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01009.x. PMID 20002219.

- Schoevers, Eric J.; Santos, Regiane R.; Colenbrander, Ben; Fink-Gremmels, Johanna; Roelen, Bernard A.J. (August 2012). "Transgenerational toxicity of Zearalenone in pigs". Reproductive Toxicology. 34 (1): 110–119. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.03.004.

- Hueza, Isis; Raspantini, Paulo; Raspantini, Leonila; Latorre, Andreia; Górniak, Silvana (2014). "Zearalenone, an Estrogenic Mycotoxin, Is an Immunotoxic Compound". Toxins. 6 (3): 1080–1095. doi:10.3390/toxins6031080. ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 3968378. PMID 24632555.

External links

- Eriksen, G. S.; Pennington, J.; Schlatter, J. (2000). "Zearalenone". WHO International Programme on Chemical Safety - Safety Evaluation of Certain Food Additives and Contaminants. Inchem. WHO Food Additives Series: 44.