History of Indian influence on Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia was under Indian sphere of cultural influence starting around 290 BC until around the 15th century, when Hindu-Buddhist influence was absorbed by local politics. Kingdoms in the southeast coast of the Indian Subcontinent had established trade, cultural and political relations with Southeast Asian kingdoms in Burma, Thailand, Indonesia, Malay Peninsula, Philippines, Cambodia and Champa. This led to Indianisation and Sanskritisation of Southeast Asia within Indosphere, Southeast Asian polities were the Indianised Hindu-Buddhist Mandala (polities, city states and confederacies).

Unlike the other kingdoms within the Indian subcontinent, the Pallava empire of the southeastern coast of the India peninsula did not have culture restrictions on crossing the sea. Chola empire also had profound impact on Southeast Asia, who executed South-East Asia campaign of Rajendra Chola I and Chola invasion of Srivijaya. This led to more exchanges through the sea routes into Southeast Asia. Whereas Buddhism thrived and became the main religion in many countries of the Southeast Asia, it died off on the Indian subcontinent.

The peoples of maritime Southeast Asia — present day Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines — are thought to have migrated southwards from southern China sometime between 2500 and 1500 BC. The influence of the civilization of the subcontinent gradually became predominant among them, and among the peoples of the Southeast Asian mainland.

Southern Indian traders, adventurers, teachers and priests continued to be the dominating influence in Southeast Asia until about 1500 CE. Hinduism and Buddhism both spread to these states from India and for many centuries existed there with mutual toleration. Eventually the states of the mainland became mainly Buddhist.

Brunei

Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms (? - ~1400)

The history of Brunei before the arrival of Magellan's ships in 1519-1522 CE is based on the interpretation of Chinese sources and local legends. Historians believe that there was a forerunner Indianised Hindu-Buddhist state to the present day Brunei Sultanate. One predecessor state was called Vijayapura, which possibly existed in northwest Borneo in the 7th century.[lower-alpha 1] It was probably a subject state of the powerful Indianised Hindu-Buddhist Srivijaya empire based in Sumatra. One predecessor state was called Po-ni (pinyin: Boni).[2] By the 10th century Po-ni had contacts with first the Song dynasty and at some point even entered into a tributary relationship with China. By the 14th century Po-ni also fell under the influence of the Indianised Hindu Javanese Majapahit Empire. The book of Nagarakretagama, canto 14, written by Prapanca in 1365 mentioned Berune as a vassal state of Majahpahit.[3] However this may have been nothing more than a symbolic relationship, as one account of the annual tribute owed each year to Majahpahit was a jar of areca juice obtained from the young green nuts of the areca palm. The Ming dynasty resumed communications with Po-ni in the 1370s and the Po-ni ruler Ma-na-jih-chia-na visited the Ming capital Nanjing in 1408 and died there; his tomb was rediscovered in the 20th century, and is now a protected monument.

Indianised Islamic sultanate (~1400 - present day)

In 1402, Sultan Muhammad Shah died, he was first to convert from Hindu-Buddhism to Islam, and his pre-conversion name was Awang Alak Betatar.

Burma (Myanmar)

At the western end of the South East Asian mainland, Lower Burma was occupied by the Mon peoples who are thought to have come originally from western China. In Lower Burma they supplanted an earlier people: the Pyu, of whom little is known except that they practised Hinduism.

Arrival of Buddhism and impact of Indian literature (3rd century CE onward)

The Mons strongly influenced by their contacts with Indian traders during the 3rd century B.C adopted Indian literature and art and the Buddhist religion. The Mons were the earliest known civilization in Southeast Asia. They consisted of several Mon kingdoms, spreading from Lower Burma into much of Thailand, where they founded the kingdom of Dvaravati. Their principal settlements in Burma were Thaton and Pegu.

Tibeto-Burman Buddhist kingdoms (11th - 13th century CE )

From about the 9th century onward Tibeto-Burman tribes moved south from the hills east of Tibet into the Irrawaddy plain. They founded their capital at Pagan in Upper Burma in the 10th century. They eventually absorbed the Mons, their cities and adopted the Mon civilization and Buddhism. The Pagan kingdom united all Burma under one rule for 200 years - from the 11th to 13th centuries. The zenith of its power occurred during the reign of King Anawratha (1044–1077), who conquered the Mon kingdom of Thaton. King Anawratha built many of the temples for which Pagan is famous. It is estimated that some 13,000 temples once existed within the city, which some 5,000 still stand.

Cambodia

Funan

The first of these Hinduised states to achieve widespread importance was the Kingdom of Funan founded in the 1st century CE in what is now Cambodia — according to legend, after the marriage of a Brahman into the family of the local chief. These local inhabitants were Khmer people. Funan flourished for some 500 years. It carried on a prosperous trade with India and China, and its engineers developed an extensive canal system. An elite practised statecraft, art and science, based on Indian culture. Vassal kingdoms spread to southern Vietnam in the east and to the Malay Peninsula in the west.

Chenla and Angkor

In late 6th century CE, dynastic struggles caused the collapse of the Funan empire. It was succeeded by another Hindu-Khmer state, Chen-la, which lasted until the 9th century. Then a Khmer king, Jayavarman II (about 800-850) established a capital at Angkor in central Cambodia. He founded a cult which identified the king with the Hindu God Shiva – one of the triad of Hindu gods, Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, Shiva the god symbolising destruction and reproduction. The Angkor empire flourished from the 9th to the early 13th century. It reached the peak of its fame under Jayavarman VII at the end of the 12th century, when its conquests extended into Thailand in the west (where it had conquered the Mon kingdom of Dwaravati) and into Champa in the east. Its most celebrated memorial is the great temple of Angkor Wat, built early in the 12th century. This summarises the position on the South East Asian mainland until about the 12th century. Meanwhile, from about the 6th century, and until the 14th century, there was a series of great maritime empires based on the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Java. In early days these Indians came mostly from the ancient kingdom of Kalinga, on the southeastern coast of India. Indians in Indonesia are still known as "Klings", derived from Kalinga.

East Timor

The later Timorese were not seafarers, rather they were land focused peoples who did not make contact with other islands and peoples by sea. Timor was part of a region of small islands with small populations of similarly land-focused peoples that now make up eastern Indonesia. Contact with the outside world was via networks of foreign seafaring traders from as far as China and India that served the archipelago. Outside products brought to the region included metal goods, rice, fine textiles, and coins exchanged for local spices, sandalwood, deer horn, bees' wax, and slaves.[4]

Indianised Javanese Hindu-Buddhist Srivijaya empire (7th - 12th century)

Oral traditions of people of Wehali principality of East Timor mention their migration from Sina Mutin Malaka or "Chinese White Malacca" (part of Indianised Hindu-Buddhist Srivijaya empire) in ancient times.[5]

As vassal of Indianised Javanese Hindu empire of Majapahit (12th - 16th century)

Nagarakretagama, the chronicles of the Majapahit empire called Timor a tributary,[6] but as Portuguese chronologist Tomé Pires wrote in the 16th century, all islands east of Java were called "Timor".[7] Indonesian nationalist used the Majapahit chronicles to claim East Timor as part of Indonesia.[8]

Trade with China

Timor is mentioned in the 13th-century Chinese Zhu Fan Zhi, where it is called Ti-wu and is noted for its sandalwood. It is called Ti-men in the History of Song of 1345. Writing towards 1350, Wang Dayuan refers to a Ku-li Ti-men, which is a corruption of Giri Timor, meaning island of Timor.[9] Giri from "mountain" in Sanskrit, thus "mountainous island of Timor".

Chiefdoms or polities

Early European explorers report that the island had a number of small chiefdoms or princedoms in the early 16th century. One of the most significant is the Wehali or Wehale kingdom in central Timor, to which the Tetum, Bunak and Kemak ethnic groups were aligned.[10] Early European explorers report that the island had a number of small chiefdoms or princedoms in the early 16th century. One of the most significant is the Wehali or Wehale kingdom in central Timor, to which the Tetum, Bunak and Kemak ethnic groups were aligned.[10]

European colonisation and Christianisation (16th century onward)

Beginning in the early sixteenth century, European colonialists—the Dutch in the island's west, and Portuguese in the east—would divide the island, isolating the East Timorese from the histories of the surrounding archipelago.[6]

Indonesia

Approximately for more than a millennia, between 5th to 15th centuries, the various Indianised states and empires flourished in the Indonesian archipelago; from the era of Tarumanagara to Majapahit. Though founded possibly by either early Indian settlers or by native polities that adopted Indian culture, and have maintaining diplomatic contacts with India, these archipelagic Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms remained politically independent from the kingdoms of Indian subcontinent. Together with Cambodia and Champa, the Hindu-Buddhist civilization of Java was one of the most beautiful jewel of the Dharmic civilization ever flourished in Southeast Asia.

Srivijaya empire

The Indonesian archipelago saw the rise of Hindu-Buddhist empires of Sumatra and Java. In the islands of Southeast Asia, one of the first organised state to achieve fame was the Buddhist Malay kingdom of Srivijaya, with its capital at Palembang in southern Sumatra. Its commercial pre-eminence was based on command of the sea route from India to China between Sumatra and the Malay peninsula (later known as the Straits of Malacca). In the 6th – 7th centuries Srivijaya succeeded Funan as the leading state in Southeast Asia. Its ruler was the overlord of the Malay peninsula and western Java as well as Sumatra. During the era of Srivijaya, Buddhism became firmly entrenched there.

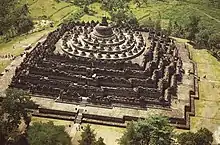

Sailendra kingdom

The expansion of Srivijaya was resisted in eastern Java, where the powerful Buddhist Sailendra dynasty arose. From the 7th century onwards there was great activity in temple building in central Java. The most impressive of the ruins is at Borobudur, considered to have been the largest Buddhist temple in the world. Sailendra rule spread to southern Sumatra, and up to Malay peninsula to Cambodia (where it was replaced by the Angkorian kingdom). In the 9th century, the Sailendras moved to Sumatra, and a union of Srivijaya and the Sailendras formed an empire which dominated much of Southeast Asia for the next five centuries. After 500 Years of supremacy, Srivijaya was superseded by Majapahit.

Mataram kingdom

In the 10th century, Mataram to the challenged the supremacy of Srivijaya, resulting in the destruction of the Mataram capital by Srivijaya early in the 11th century. Restored by King Airlangga (c. 1020–1050), the kingdom split on his death and the new state of Kediri was formed in eastern Java.

Kediri kingdom

Kediri kingdom, spread its influence to the eastern part of Southeast Asia and became the centre of Javanese culture for the next two centuries. The spice trade was now becoming of increasing importance, as the demand by European countries for spices grew. Before they learned to keep sheep and cattle alive in the winter, they had to eat salted meat, made palatable by the addition of spices. One of the main sources was the Maluku Islands (or "Spice Islands") in Indonesia, and Kediri became a strong trading nation.

Singhasari kingdom

In the 13th century, however, the Kediri dynasty was overthrown by a revolution, and Singhasari arose in east Java. The domains of this new state expanded under the rule of its warrior-king Kertanegara. He was killed by a prince of the previous Kediri dynasty, who then established the last great Hindu-Javanese kingdom, Majapahit.

Majapahit empire

With the departure of the Sailendras and the fall of Singhasari, a new Majapahit kingdom appeared in eastern Java, which reverted from Buddhism to Hinduism. By the middle of the 14th century, Majapahit controlled most of Java, Sumatra and the Malay peninsula, part of Borneo, the southern Celebes and the Moluccas. It also exerted considerable influence on the mainland.

Laos

Funan kingdom

The first indigenous kingdom to emerge in Indochina was referred to in Chinese histories as the Kingdom of Funan and encompassed an area of modern Cambodia, and the coasts of southern Vietnam and southern Thailand since the 1st century CE. Funan was an Indianised kingdom, that had incorporated central aspects of Indian institutions, religion, statecraft, administration, culture, epigraphy, writing and architecture and engaged in profitable Indian Ocean trade.[11][12]

Champa kingdom

By the 2nd century CE, Austronesian settlers had established an Indianised kingdom known as Champa along modern central Vietnam. The Cham people established the first settlements near modern Champasak in Laos. Funan expanded and incorporated the Champasak region by the sixth century CE, when it was replaced by its successor polity Chenla. Chenla occupied large areas of modern-day Laos as it accounts for the earliest kingdom on Laotian soil.[12][13]

Chenla kingdom

The capital of early Chenla was Shrestapura which was located in the vicinity of Champasak and the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Wat Phu. Wat Phu is a vast temple complex in southern Laos which combined natural surroundings with ornate sandstone structures, which were maintained and embellished by the Chenla peoples until 900 CE, and were subsequently rediscovered and embellished by the Khmer in the 10th century. By the 8th century CE Chenla had divided into “Land Chenla” located in Laos, and “Water Chenla” founded by Mahendravarman near Sambor Prei Kuk in Cambodia. Land Chenla was known to the Chinese as “Po Lou” or “Wen Dan” and dispatched a trade mission to the Tang Dynasty court in 717 CE. Water Chenla, would come under repeated attack from Champa, the Medang sea kingdoms in Indonesia based in Java, and finally pirates. From the instability the Khmer emerged.[14]

Khmer kingdom

Under the king Jayavarman II the Khmer Empire began to take shape in the 9th century CE.[14][15]

Dvaravati city state kingdoms

In the area which is modern northern and central Laos, and northeast Thailand the Mon people established their own kingdoms during the 8th century CE, outside the reach of the contracting Chenla kingdoms. By the 6th century in the Chao Phraya River Valley, Mon peoples had coalesced to create the Dvaravati kingdoms. In the 8th century CE, Sri Gotapura (Sikhottabong) was the strongest of these early city states, and controlled trade throughout the middle Mekong region. The city states were loosely bound politically, but were culturally similar and introduced Therevada Buddhism from Sri Lankan missionaries throughout the region.[16][17]

Malaysia

The Malay peninsula was settled by prehistoric people 80,000 years ago. Another batch of peoples the deutro Malay migrated from southern China within 10,000 years ago. Upon arrival in the peninsular some of them mix with the Australoid. This gave the appearance of the Malays. It was suggested that the visiting ancient Dravidians named the peoples of Malaysia peninsular and Sumatera as "Malay ur" meant hills and city based on the geographical terrain of Peninsular Malay and Sumatera. Claudius Ptolemaeus (Greek: Κλαύδιος Πτολεμαῖος; c. 90 – c. 168), known in English as Ptolemy, was a Greek geographer, astronomer, and astrologer who had written about Golden Chersonese, which indicates trade with the Indian Sub-Continent and China has existed since the 1st century AD.[18] Archeologist have found relic and ruin in Bujang Valley settlement dating back at 110AD. The settlement is believed to be the oldest civilization in Southeast Asia influenced by ancient Indians. Today, Malaysians of direct Indian descent account for approximately 7 per cent of the total population of Malaysia (approximately. 2 million)

Hinduism and Buddhism from India dominated early regional history, reaching their peak during the reign of the Sumatra-based Srivijaya civilisation, whose influence extended through Sumatra, Java, the Malay Peninsula and much of Borneo from the 7th to the 13th centuries, which later gradually defeated and converted to Islam in 14th and 15th century before the erupean colonisation began in 16th century.

Early trade and Indian settlements

In the first millennium CE, Malays became the dominant race on the peninsula. The small early states that were established were greatly influenced by Indian culture, as was most of Southeast Asia.[19] Indian influence in the region dates back to at least the 3rd century BCE. South Indian culture was spread to Southeast Asia by the south Indian Pallava dynasty in the 4th and 5th century.[20]

In ancient Indian literature, the term Suvarnadvipa or the "Golden Peninsula" is used in Ramayana, and some argued that it may be a reference to the Malay Peninsula. The ancient Indian text Vayu Purana also mentioned a place named Malayadvipa where gold mines may be found, and this term has been proposed to mean possibly Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula.[21] The Malay Peninsula was shown on Ptolemy's map as the "Golden Khersonese". He referred to the Straits of Malacca as Sinus Sabaricus.[22]

Trade relations with China and India were established in the 1st century BC.[23] Shards of Chinese pottery have been found in Borneo dating from the 1st century following the southward expansion of the Han Dynasty.[24] In the early centuries of the first millennium, the people of the Malay Peninsula adopted the Indian religions of Hinduism and Buddhism, religions which had a major effect on the language and culture of those living in Malaysia.[25] The Sanskrit writing system was used as early as the 4th century.[26]

Indianised Hindu Malay kingdoms (3rd century to 7th century)

There were numerous Malay kingdoms in the 2nd and 3rd century, as many as 30, mainly based on the Eastern side of the Malay peninsula.[19] Among the earliest kingdoms known to have been based in the Malay Peninsula is the ancient kingdom of Langkasuka, located in the northern Malay Peninsula and based somewhere on the west coast.[19] It was closely tied to Funan in Cambodia, which also ruled part of northern Malaysia until the 6th century. In the 5th century, the Kingdom of Pahang was mentioned in the Book of Song. According to the Sejarah Melayu ("Malay Annals"), the Khmer prince Raja Ganji Sarjuna founded the kingdom of Gangga Negara (modern-day Beruas, Perak) in the 700s. Chinese chronicles of the 5th century CE speak of a great port in the south called Guantoli, which is thought to have been in the Straits of Malacca. In the 7th century, a new port called Shilifoshi is mentioned, and this is believed to be a Chinese rendering of Srivijaya.

Indianised Hindu-Buddhist Malay kingdoms as vassal of Srivijaya empire (7th - 13th century)

Between the 7th and the 13th century, much of the Malay peninsula was under the Buddhist Srivijaya empire. The site of Srivijaya's centre is thought be at a river mouth in eastern Sumatra, based near what is now Palembang.[27] For over six centuries the Maharajahs of Srivijaya ruled a maritime empire that became the main power in the archipelago. The empire was based around trade, with local kings (dhatus or community leaders) swearing allegiance to the central lord for mutual profit.[28]

Relationship of Srivijaya empire with Indian Tamil Chola empire

Chola empire also had profound impact on Southeast Asia, who executed South-East Asia campaign of Rajendra Chola I and Chola invasion of Srivijaya.

The relation between Srivijaya and the Chola Empire of south India was friendly during the reign of Raja Raja Chola I but during the reign of Rajendra Chola I the Chola Empire invaded Srivijaya cities.[29] In 1025 and 1026 Gangga Negara was attacked by Rajendra Chola I of the Chola Empire, the Tamil emperor who is now thought to have laid Kota Gelanggi to waste. Kedah—known as Kedaram, Cheh-Cha (according to I-Ching) or Kataha, in ancient Pallava or Sanskrit—was in the direct route of the invasions and was ruled by the Cholas from 1025. A second invasion was led by Virarajendra Chola of the Chola dynasty who conquered Kedah in the late 11th century.[30] The senior Chola's successor, Vira Rajendra Chola, had to put down a Kedah rebellion to overthrow other invaders. The coming of the Chola reduced the majesty of Srivijaya, which had exerted influence over Kedah, Pattani and as far as Ligor. During the reign of Kulothunga Chola I Chola overlordship was established over the Srivijaya province kedah in the late 11th century.[31] The expedition of the Chola Emperors had such a great impression to the Malay people of the medieval period that their name was mentioned in the corrupted form as Raja Chulan in the medieval Malay chronicle Sejarah Melaya.[32][33][34] Even today the Chola rule is remembered in Malaysia as many Malaysian princes have names ending with Cholan or Chulan, one such was the Raja of Perak called Raja Chulan.[35][36]

Pattinapalai, a Tamil poem of the 2nd century CE, describes goods from Kedaram heaped in the broad streets of the Chola capital. A 7th-century Indian drama, Kaumudhimahotsva, refers to Kedah as Kataha-nagari. The Agnipurana also mentions a territory known as Anda-Kataha with one of its boundaries delineated by a peak, which scholars believe is Gunung Jerai. Stories from the Katasaritasagaram describe the elegance of life in Kataha. The Buddhist kingdom of Ligor took control of Kedah shortly after. Its king Chandrabhanu used it as a base to attack Sri Lanka in the 11th century and ruled the northern parts, an event noted in a stone inscription in Nagapattinum in Tamil Nadu and in the Sri Lankan chronicles, Mahavamsa.

Decline of Srivijaya empire and inner fights of breakup vassal states (12th - 13th century)

At times, the Khmer kingdom, the Siamese kingdom, and even Cholas kingdom tried to exert control over the smaller Malay states.[19] The power of Srivijaya declined from the 12th century as the relationship between the capital and its vassals broke down. Wars with the Javanese caused it to request assistance from China, and wars with Indian states are also suspected. In the 11th century, the centre of power shifted to Malayu, a port possibly located further up the Sumatran coast near the Jambi River.[28] The power of the Buddhist Maharajas was further undermined by the spread of Islam. Areas which were converted to Islam early, such as Aceh, broke away from Srivijaya's control. By the late 13th century, the Siamese kings of Sukhothai had brought most of Malaya under their rule. In the 14th century, the Hindu Java-based Majapahit empire came into possession of the peninsula.[27]

Defeat and conversion to Islamic sultanates in 14th and 15th century

In the 14th century that first Islamic sultanate was established. The adoption of Islam in the 14th century saw the rise of a number of sultanates, the most prominent of which was the Sultanate of Malacca. Islam had a profound influence on the Malay people. The Portuguese were the first European colonial powers to establish themselves on the Malay Peninsula and Southeast Asia, capturing Malacca in 1511, followed by the Dutch in 1641. However, it was the British who, after initially establishing bases at Jesselton, Kuching, Penang and Singapore, ultimately secured their hegemony across the territory that is now Malaysia. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 defined the boundaries between British Malaya and the Netherlands East Indies (which became Indonesia). A fourth phase of foreign influence was immigration of Chinese and Indian workers to meet the needs of the colonial economy created by the British in the Malay Peninsula and Borneo.[37]

European colonisation and modern era (16th century - present day)

Colonisation commenced form European colonisation from 16th century and ended in 19th century.

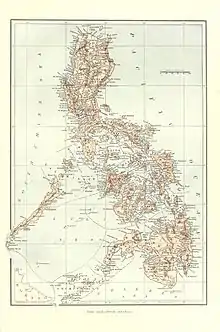

Philippines

Indianised kingdoms in Philippines

- Super kingdoms spanning several present day nations

- Srivijaya empire: a Hindu-Buddhist kingdom also included Luzon and Visayas, rival of Mataram who also ruled Mindanao

- Kingdom of Mataram: a Hindu kingdom rival of Buddhist Srivijara, its king was Balitung mentioned in the Balitung inscription, spread across Java in southern Indonesia and Sulu/Mindanao in southern Philippines

- Super kingdoms spanning several present day nations

- Luzon

- Around Manila and Pasig river were 3 polities which were earlier HinduBuddhist, later Islamic and then subsumed and converted to Catholicism by Spanish in 16th century

- Namayan polity was confederation of barangays

- Maynila (historical entity)

- Rajah Sulayman (also Sulayman III, 1558–1575), Indianized Kingdom of Maynila

- Rajah Matanda (1480–1572), ruler of the Indianized Kingdom of Maynila, together with Rajah Sulayman was co-ruled Maynila, their cousin Lakan Dula ruled Tondo. Rajah Sulayman was one of three kings that ruled parts of present-day Manila, and fought against the Spanish Empire's colonisation of the Philippines

- Tondo (Historical State) on Pasig river near Manila

- Lakan Dula, was a raja who was cousin of Rajah Sulayman and Rajah Matanda

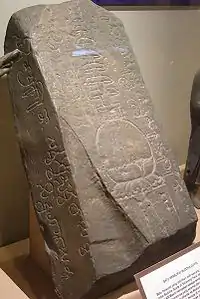

- Laguna Copperplate Inscription, earliest known written document found in the Philippines, in Indianized Kawi script with Sanskrit loanwords

- Ma-i Buddhist kingdom of Mindoro island, from before 10th century till 14th century

- 1406–1576 Caboloan,[38] was a sovereign pre-colonial Philippine polity located in the fertile Agno River basin and delta, with Binalatongan as the capital.[39] The polity of Pangasinan sent emissaries to China in 1406–1411.[40]

- Around Manila and Pasig river were 3 polities which were earlier HinduBuddhist, later Islamic and then subsumed and converted to Catholicism by Spanish in 16th century

- Luzon

- Visayas

- Rajahnate of Cebu at Singhapala (Mabolo in Cebu city on Mahinga creej) capital city in southern Cebu island was Hindu-kingdom founded by Sri Lumay or Rajamuda Lumaya, a minor prince of the Chola dynasty of India which occupied Sumatra. He was sent by the Maharajah from India to establish a base for expeditionary forces, but he rebelled and established his own independent rajahnate.[41] Subsumed by Spanish in 16th century.

- King Sri Lumay was half Tamil and half Malay, noted for his strict policies in defending against Moro Muslim raiders and slavers from Mindanao. His use of scorched earth tactics to repel invaders gave rise to the name Kang Sri Lumayng Sugbu (literally "that of Sri Lumay's great fire") to the town, which was later shortened to Sugbu ("scorched earth").

- Sri Bantug, king and successor son of Sri Lumay

- Rajah Humabon, king and successor son of Sri Batung

- Battle of Mactan on 27 April 1521 between Rajah Humabon and Ferdinand Magellan in which Lapu-Lapu fought on side of Rajah, resulting in the death of Ferdinand Magellan.

- Lapu-Lapu, warrior under Rajah Humabon, Lapu-Lapu fought Spanish

- Ferdinand Magellan, Portuguese explorer on hired by Spanish empire

- Rajah Tupas (Sri Tupas), nephew and successor of Rajah Humabon, last to rule the kingdom before subsumed by Spanish Miguel López de Legazpi in the battle of Cebu during 1565.

- Caste system: Below the rulers were the Timawa, the feudal warrior class of the ancient Visayan societies of the Philippines who were regarded as higher than the uripon (commoners, serfs, and slaves) but below the Tumao (royal nobility) in the Visayan social hierarchy. They were roughly similar to the Tagalog maharlika caste. Lapu Lapu was a Timawa.

- A crude Buddhist medallion and a copper statue of a Hindu Deity, Ganesha, has been found by Henry Otley Beyer in 1921 in ancient sites in Puerto Princesa, Palawan and in Mactan, Cebu.[42] The crudeness of the artifacts indicates they are of local reproduction. Unfortunately, these icons were destroyed during World War II. However, black and white photographs of these icons survive.

- Kedatuan of Madja-as of Panay island was a supra-baranganic polity from 14th century till 16th century until subsumed by Spanish, were migrants from North Sumatra in Indonesia where they were rulers of Buddhist Srivihayan "kingdom of Pannai" (ruled 10 to 14th century) which was defeated by Majapahit.

- Rajahnate of Cebu at Singhapala (Mabolo in Cebu city on Mahinga creej) capital city in southern Cebu island was Hindu-kingdom founded by Sri Lumay or Rajamuda Lumaya, a minor prince of the Chola dynasty of India which occupied Sumatra. He was sent by the Maharajah from India to establish a base for expeditionary forces, but he rebelled and established his own independent rajahnate.[41] Subsumed by Spanish in 16th century.

- Mindanao

- Kingdom of Butuan in northeast Mindanao, Hindu kingdom existed earlier than 10th century and ruled till being subsumed by Spanish in 16th century

- Golden Tara (Agusan image) is a golden statue that was found in Agusan del Sur in northeast Mindanao.

- Mount Diwata: named after diwata concept of Philippines based on the devata deity concept of Hinduism

- Sultanate of Lanao of Muslims in Maguindanao in northwestern Mindanao from 15th century till present day

- Sultanate of Maguindanao in Cotabato in far west Mindanao from split from Srivijaya Hindu ancestors in 16th century and ruled till early 20th century, originally converted by sultan of Johor in 16th century but maintained informal kinship with Hindu siblings who are now likely Christians

- Sultanate of Sulu in southwestern Mindanao, established in 1405 by a Johore-born Muslim explorer, gained independence from the Bruneian Empire in 1578 and lasted till 1986. It also covered the area in northeastern side of Borneo, stretching from Marudu Bay to Tepian Durian in present-day Kalimantan.

- Lupah Su sultanate, predecessor Islamic state before the establishment of Sultanate of Sulu.[43]

- Maimbung principality: Hindu polity, predecessor of Lupah Su]] Muslim sultanate. Sulu that time was called Lupah Sug[43] The Principality of Maimbung, populated by Buranun people (or Budanon, literally means "mountain-dwellers"), was first ruled by a certain rajah who assumed the title Rajah Sipad the Older. According to Majul, the origins of the title rajah sipad originated from the Hindu sri pada, which symbolises authority.[44] The Principality was instituted and governed using the system of rajahs. Sipad the Older was succeeded by Sipad the Younger.

- Kingdom of Butuan in northeast Mindanao, Hindu kingdom existed earlier than 10th century and ruled till being subsumed by Spanish in 16th century

- Visayas

Indians in Philippines during colonial era

- 1762–1764 British Manila

- Battle of Manila (1762) by the East India Company's Indian soldiers during Anglo-Spanish War (1761–63)

- Cainta in Rizal: historic colonial era settlement of escaped Indians sepoys of British East India Company

- Indian Filipino: Filipino citizens with part or whole Indian blood

Key Indianised Hindu-Buddhist artifacts found in Philippines

- Luzon

- Laguna Copperplate Inscription in Luzon, earliest known written document found in the Philippines, in Indianized Kawi script with Sanskrit loanwords

- Palawan Tabon Caves Garuda Gold Pendant found in the Tabon caves in the island of Palawan, is an image of Garuda, the eagle bird who is the mount of Hindu deity Vishnu[45]

- Visayas

- Rajahnate of Cebu Buddhist medallion and copper statue of Hindu Deity: A crude Buddhist medallion and a copper statue of a Hindu Deity, Ganesha, has been found by Henry Otley Beyer in 1921 in ancient sites in Puerto Princesa, Palawan and in Mactan, Cebu.[42] The crudeness of the artifacts indicates they are of local reproduction. Unfortunately, these icons were destroyed during World War II. However, black and white photographs of these icons survive.

- Mindanao

- Golden Tara (Agusan image) from Kingdom of Butuan in northeast Mindanao is a golden statue that was found in Agusan del Sur in northeast Mindanao.

Singapore

The Greco-Roman astronomer Ptolemy (90–168) identified a place called Sabana at the tip of Golden Chersonese (believed to be the Malay Peninsula) in the second and third century.[46] The earliest written record of Singapore may be in a Chinese account from the third century, describing the island of Pu Luo Chung (蒲 羅 中). This is thought to be a transcription from the Malay name "Pulau Ujong", or "island at the end" (of the Malay Peninsula).[47]

In 1025 CE, Rajendra Chola I of the Chola Empire led forces across the Indian Ocean and invaded the Srivijayan empire, attacking several places in Malaysia and Indonesia.[48][49] The Chola forces were said to have controlled Temasek (now Singapore) for a couple of decades.[50] The name Temasek however did not appear in Chola records, but a tale involving a Raja Chulan (assumed to be Rajendra Chola) and Temasek was mentioned in the semi-historical Malay Annals.[51]

The Nagarakretagama, a Javanese epic poem written in 1365, referred to a settlement on the island called Tumasik (possibly meaning "Sea Town" or "Sea Port").[52]

Hindu-Buddhist kingdom (? - ~1511)

The name Temasek is also given in Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals), which contains a tale of the founding of Temasek by a prince of Srivijaya, Sri Tri Buana (also known as Sang Nila Utama) in the 13th century. Sri Tri Buana landed on Temasek on a hunting trip, and saw a strange beast said to be a lion. The prince took this as an auspicious sign and founded a settlement called Singapura, which means "Lion City" in Sanskrit. The actual origin of the name Singapura however is unclear according to scholars.[53]

In 1320, the Mongol Empire sent a trade mission to a place called Long Ya Men (or Dragon's Teeth Gate), which is believed to be Keppel Harbour at the southern part of the island.[54] The Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan, visiting the island around 1330, described Long Ya Men as one of the two distinct settlements in Dan Ma Xi (from Malay Temasek), the other being Ban Zu (from Malay pancur). Ban Zu is thought to be present day Fort Canning Hill, and recent excavations in Fort Canning found evidence indicating that Singapore was an important settlement in the 14th century.[55][56] Wang mentioned that the natives of Long Ya Men (thought to be the Orang Laut) and Chinese residents lived together in Long Ya Men.[57][58] Singapore is one of the oldest locations where a Chinese community is known to exist outside China, and the oldest corroborated by archaeological evidence.[59]

Sometime in its history, the name of Temasek was changed to Singapura. The Sejarah Melayu (Malay Annals) contains a tale of a prince of Srivijaya, Sri Tri Buana (also known as Sang Nila Utama), who landed on Temasek after surviving a storm in the 13th century. According to the tale, the prince saw a strange creature, which he was told was a lion; believing this to be an auspicious sign, he decided to found a settlement called Singapura, which means "Lion City" in Sanskrit. It is unlikely there ever were lions in Singapore, though tigers continued to roam the island until the early 20th century. However, the lion motif is common in Hindu mythology, which was dominant in the region during that period (one of the words for "throne" in the Malay language is "singgasana", meaning "lion's seat" in Sanskrit), and it has been speculated that the "Singapura" name, and the tale of the lion, were invented by court historians of the Malacca Sultanate to glorify Sang Nila Utama and his line of descent.[60]

Different versions of its history are told in Portuguese sources, suggesting that Temasek was a Siamese vassal whose ruler was killed by Parameswara from Palembang.[61] Historians believe that during the late 14th century, Parameswara, the last Srivijayan prince, fled to Temasek from Palembang after being deposed by the Majapahit Empire. According to Portuguese accounts, Parameswara killed the local chief with the title Sang Aji eight days after being welcomed into Temasek.[62]

By the 14th century, the empire of Srivijaya had already declined, and Singapore was caught in the struggle between Siam (now Thailand) and the Java-based Majapahit Empire for control over the Malay Peninsula. According to the Malay Annals, Singapore was defeated in one Majapahit attack. The last king, Sultan Iskandar Shah (a prince of Srivijaya empire, his Hindu name Parameswara before he was converted to Islam) ruled the island for several years, before being forced to Melaka where he founded the Sultanate of Malacca.[63] Portuguese sources however indicated that Temasek was a Siamese vassal whose ruler was killed by Parameswara (thought to be the same person as Sultan Iskandar Shah) from Palembang, and Parameswara was then driven to Malacca, either by the Siamese or the Majapahit, where he founded the Malacca Sultanate.[64] Modern archaeological evidence suggests that the settlement on Fort Canning was abandoned around this time, although a small trading settlement continued in Singapore for some time afterwards.[53]

Islamic sultanate (1511 - 1613)

The Malacca Sultanate extended its authority over the island and Singapore became a part of the Malacca Sultanate.[47] However, by the time the Portuguese arrived in the early 16th century, Singapura had already become "great ruins" according to Alfonso de Albuquerque.[65][66] In 1511, the Portuguese seized Malacca; the sultan of Malacca escaped south and established the Johor Sultanate, and Singapore then became part of the sultanate which was destroyed in 1613.[67]

Thailand

Thailand's relationship with India spans over a thousand years and understandably resulted in an adaptation of Hindu culture to suit the Thai environment. Evidence of strong religious, cultural and linguistic links abound.

Propagation of Buddhism in Thailand by emperor Ashoka (3rd century BCE)

Historically, the cultural and economic interaction between the two countries can be traced to roughly around the 6th century B.C. The single most significant cultural contribution of India, for which Thailand is greatly indebted to India, is Buddhism. Propagated in Thailand in the 3rd century B.C. by Buddhist monks sent by King Asoka, it was adopted as the state religion of Thailand and has ruled the hearts and minds of Thais ever since. Presently 58,000,000 Thais, an overwhelming 94% of the total Thai populace adheres to Buddhism. However, direct contact can be said to have begun only in the 3rd century B.C. when King Asoka sent Buddhist monks to propagate Buddhism in the Indo-Chinese peninsula. Besides Buddhism, Thailand has also adopted other typically Indian religious and cultural traditions. The ceremonies and rites especially as regards the Monarchy evidence a strong Hindu influence.

Sukhothai period: Settlement of Indian traders and Brahmins in Thailand (1275–1350)

The Indians who moved into Thailand in the Sukhothai period (1275–1350) were either merchants who came to Siam or Thailand, for the purpose of trading or Brahmans who played an important role in the Siamese court as experts in astrology and in conducting ceremonies. The first group of Brahmans who entered Siam before the founding of Sukhothai as the first capital of Siam (1275–1350) popularized Hindu beliefs and traditions. During the Sukhothai period Brahman temples already existed. Brahmans conducted ceremonies in the court. The concepts of divine kingship and royal ceremonies are clear examples of the influence of Brahmanism.

The Coronation of the Thai monarch are practiced more or less in its original form even up to the present reign. The Thai idea that the king is a reincarnation of the Hindu deity Vishnu was adopted from Indian tradition. (Though this belief no longer exists today, the tradition to call each Thai king of the present Chakri dynasty Rama (Rama is an incarnation of Vishnu) with an ordinal number, such as Rama I, Rama II etc. is still in practice.)

Ayutthaya period: Settlement of more Indian Tamil traders in Thailand (1350–1767 CE)

In the Ayutthaya kingdom era (1350–1767), more Tamil merchants entered the South of the country by boat as evidenced by the statues of Hindu gods excavated in the South.

Later migration of Indians to Thailand (1855 CE - present day)

After the year 1855, the Tamils who migrated to Thailand can be classified into three groups according to the religion they believed in, namely, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam.

Dance

Thai literature and drama draws great inspiration from Indian arts and legend. The Hindu epic of Ramayana is as popular in Thailand as it is in India. Thailand has adapted the Ramayana to suit the Thai lifestyle in the past and has come up with its own version of the Ramayana, namely, the Ramakien.

Two of the most popular classical dances the Khon, performed by men wearing ferocious masks, and the Lakhon (Lakhon nai, Lakhon chatri and Lakhon nok), performed by women who play both male and female roles draws inspiration primarily from the Ramakien. Percussion instruments and Piphat, a type of woodwind accompany the dance.[69]

In addition, there are shadow play called nang talung in Thai. This is a show in which shadows of pieces of cow or water buffalo hide cut to represent human figures with movable arms and legs are thrown on a screen for the entertainment of spectators. In South India, this kind of show is called Bommalattam.

Language

Thai language too bears close affinity with Sanskrit and Dravidian languages. An indication of the close linguistic affiliation between India and Thailand is found in common Thai words like Ratha Mantri, Vidhya, Samuthra, Karuna, Gulab, Prannee etc. which are almost identical to their Indian counterparts. Thai language basically consists of monosyllabic words that are individually complete in meaning. His Majesty King Ram Khamhaeng the Great created the Thai alphabet in 1283. He modeled it on the ancient Indian alphabets of Sanskrit and Pali through the medium of the old Khmer characters. Like most world languages, the Thai language is a complicated mixture derived from several sources. Many Thai words used today were derived from Pali, Sanskrit, Khmer, Malay, English and Chinese.[69]

Religious ceremonies and festivals

Several Thai ceremonies have been adopted from Indian tradition. These include ceremonies related to ordination, marriage, merit making and cremation. Though the Lord Buddha is the prime inspiration of Thailand, Brahma and other Hindu deities are widely worshipped among the Thais, due in part to the popularity of the Hindu ceremonial rites, which are used especially for royal ceremonies.

(1) The Triyampawai Ceremony or the Giant Swing Ceremony. Originally a Brahmin ceremony performed to pay homage to the God Shiva, it was traditionally held front of Wat Suthat, while the King and Queen watched the ceremony from a gold silk pavilion. Though the ceremony was abolished during the reign of King Rama VII due to a severe economic fall, Brahman priests are still allocated money to make offerings to God Shiva.

(2) The Royal Ploughing Ceremony, which is officiated by H.M. the king at Sanam Luang in May every year with pomp. Originally a Brahmanic rite, it was adopted to mark the beginning of the farming season as also to bless all farmers with fertility for the year.

(3) The Royal Ceremony for preparing Celestial Rice or Khao thip which was said to be originally prepared by celestial beings in honor of God Indra. A portion of the celestial rice is offered to monks while the remainder was divided in varying quantities among the royal family, courtiers and household members. The making of the ambrosial dish has come to a natural end since custom demanded that virgins alone should perform the preparation and stirring of celestial rice.

(4) The Kathina Ceremony or the period during which Buddhist monks receive new robes, which generally falls in the months of October- November.

(5) Loy Krathong – the Festival of Lights which is celebrated on the full moon night of the twelfth lunar month. The floating of Loi Krathong lanterns, which began in the Sukhothai Kingdom period, continued throughout the different stages of Thai history. The present day understanding is that the festival is celebrated as an act of worship to Chao Mae Kangka, the Goddess of the Waters, for providing the water much needed throughout the year, and as a way of asking forgiveness if they have polluted it or used it carelessly.

(6) Songkran Festival: Songkran day marks Thai New Year day. "Songkran" signifies the sun's move into the first house of the zodiac. It is similar to Indian Holi.

(7) Visakha Puja Day which is considered as the greatest Buddhist holy day as it commemorates the birth, enlightenment and death of the Lord Buddha.

Other famous ceremonial holy days include Magha Puja day, in February and Asalha Puja day in July which commemorates the day on which Lord Buddha delivered the First Sermon to his five disciples, namely, Konthanya, Vassapa, Bhattiya, Mahanama and Assashi at Esipatanamaruekathayawan (Isipatana forest at Sarnath in India) and there explained his concept of the Four Noble Truths (Ariyasai).[69]

Hindu astrology

Hindu astrology still has a great impact on several important stages of Thai life. Thai people still seek advice from knowledgeable Buddhist monks or Brahman astrologers about the auspicious or inauspicious days for conducting or abstaining from ceremonies for moving house or getting married.

Influence of Ayurveda on Thai traditional medicine and massage

According to the Thai monk Venerable Buddhadasa Bhikku's writing, ‘India's Benevolence to Thailand’, the Thais also obtained the methods of making herbal medicines (Ayurveda) from the Indians. Some plants like sarabhi of family Guttiferae, kanika or harsinghar, phikun or Mimusops elengi and bunnak or the rose chestnut etc. were brought from India.[69]

Influence of Indian cuisine and spices on Thai cuisine

Thai monk Buddhadasa Bhikku's pointed out that Thai cuisine too was influenced by Indian cuisine. He wrote that Thai people learned how to use spices in their food in various ways from Indians.[69]

Vietnam

Early Chinese vassal states

At the eastern extremity of mainland Southeast Asia, northern Vietnam was originally occupied by Austro-Asiatic peoples. However, when regional power structures shifted tribes from Southern China began to settle in these lands. About 207 BC, Triệu Đà, a Qin general, taking advantage of the temporary fragmentation of the Chinese Empire on the collapse of the Ch’in dynasty, created in northern Vietnam the kingdom of Nanyue. During the 1st century BC, Nanyue was incorporated in the Chinese Empire of the Han dynasty; and it remained a province of the empire until the fall of the Tang dynasty early in the 10th century. It then regained its independence, often as a nominal tributary kingdom of the Chinese Emperor.

Establishment of Indianised Hindu kingdom of Champa by Indonesian rulers (10th century -)

In south-central Vietnam the Chams, a people of Indonesian stock, established the Hinduised kingdom of Champa c. 400. Subject to periodic invasions by the Annamese and by the Khmers of Cambodia, Champa survived and prospered. In 1471, a Vietnamese army of approximately 260,000, invaded Champa under Emperor Lê Thánh Tông (黎聖宗). The invasion began as a consequence of Cham King's Trà Toàn attack on Vietnam in 1470. The Vietnamese committed genocide against the Cham slaughtering approximately 60,000. The Vietnamese destroyed, burnt and raided massive parts of Champa, seizing the entire kingdom. Thousands of Cham escaped to Cambodia, the remaining were forced to assimilate into Vietnamese culture. Today, only 80,000 Cham remain in Vietnam.

Influence of Indian-origin Buddhism on Vietnam via Chinese culture

Vietnam, or then known as Annam (安南; pinyin: Ānnán), experienced little Hindu influence – usually via Champa. Unlike other Southeast Asian countries (except for Singapore and the Philippines), Vietnam was influenced by the Indian-origin religion Buddhism via the strong impact of culture of China.

See also

- Spread of Indian influence

- Trading routes

- Other related

- List of Southeast Asian leaders

- Southeast Asian Games

- Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

- Tiger Cub Economies

Further reading

- Cœdès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Lokesh, Chandra, & International Academy of Indian Culture. (2000). Society and culture of Southeast Asia: Continuities and changes. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan.

- R. C. Majumdar, Study of Sanskrit in South-East Asia

- R. C. Majumdar, India and South-East Asia, I.S.P.Q.S. History and Archaeology Series Vol. 6, 1979, ISBN 81-7018-046-5.

- R. C. Majumdar, Champa, Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East, Vol.I, Lahore, 1927. ISBN 0-8364-2802-1

- R. C. Majumdar, Suvarnadvipa, Ancient Indian Colonies in the Far East, Vol.II, Calcutta,

- R. C. Majumdar, Kambuja Desa Or An Ancient Hindu Colony In Cambodia, Madras, 1944

- R. C. Majumdar, Hindu Colonies in the Far East, Calcutta, 1944, ISBN 99910-0-001-1 Ancient Indian colonisation in South-East Asia.

- R. C. Majumdar, History of the Hindu Colonization and Hindu Culture in South-East Asia

- Daigorō Chihara (1996). Hindu-Buddhist Architecture in Southeast Asia. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10512-3.

- K.P. Rao, Early Trade and Contacts between South India and Southeast Asia (300 B.C.-A.D. 200), East and West

Vol. 51, No. 3/4 (December 2001), pp. 385-394

Notes

- Not to be confused with the Indian state of the same name.

References

- Kulke, Hermann (2004). A history of India. Rothermund, Dietmar, 1933– (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203391268. OCLC 57054139.

- This view recently has been challenged. See Johannes L. Kurz "Boni in Chinese Sources: Translations of Relevant Texts from the Song to the Qing Dynasties", paper accessible under http://www.ari.nus.edu.sg/article_view.asp?id=172 (2006)

- "Naskah Nagarakretagama" (in Indonesian). Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia. Archived from the original on 23 May 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 378. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- H.J. Grijzen (1904), 'Mededeelingen omtrent Beloe of Midden-Timor', Verhandelingen van het Bataviaasch Genootschap 54, pp. 18-25.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 377. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- Population Settlements in East Timor and Indonesia Archived 2 February 1999 at the Wayback Machine – University of Coimbra

- History of Timor – Technical University Lisbon (PDF-Datei; 805 kB)

- Ptak, Roderich (1983). "Some References to Timor in Old Chinese Records". Ming Studies. 1: 37–48. doi:10.1179/014703783788755502.

- Precolonial East Timor.

- Carter, Alison Kyra (2010). "Trade and Exchange Networks in Iron Age Cambodia: Preliminary Results from a Compositional Analysis of Glass Beads". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 30. doi:10.7152/bippa.v30i0.9966. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Kenneth R. Hal (1985). Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8248-0843-3.

- National Library of Australia. Asia's French Connection : George Coedes and the Coedes Collection Archived 21 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations by Charles F. W. Higham – Chenla – Chinese histories record that a state called Chenla..." (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- "Considerations on the Chronology and History of 9th Century Cambodia by Dr. Karl-Heinz Golzio, Epigraphist – ...the realm called Zhenla by the Chinese. Their contents are not uniform but they do not contradict each other" (PDF). Khmer Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- Maha Sila Viravond. "HISTORY OF LAOS" (PDF). Refugee Educators' Network. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- M.L. Manich. "HISTORY OF LAOS (includlng the hlstory of Lonnathai, Chiangmai)" (PDF). Refugee Educators' Network. Retrieved December 29, 2017.

- Imago Mvndi. Brill Archive. 1958.

- World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7614-7642-9.

- History of Humanity: From the seventh century B.C. to the seventh century A.D. by Sigfried J. de Laet p.395

- Braddell, Roland (December 1937). "An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Times in the Malay Peninsula and the Straits of Malacca". Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 15 (3 (129)): 64–126. JSTOR 41559897.

- ASEAN Member: Malaysia Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- Derek Heng (15 November 2009). Sino–Malay Trade and Diplomacy from the Tenth through the Fourteenth Century. Ohio University Press. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-0-89680-475-3.

- Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- Ishtiaq Ahmed; Professor Emeritus of Political Science Ishtiaq Ahmed (4 May 2011). The Politics of Religion in South and Southeast Asia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-136-72703-0.

- Stephen Adolphe Wurm; Peter Mühlhäusler; Darrell T. Tryon (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- "Malaysia". State.gov. 14 July 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- Barbara Watson Andaya; Leonard Y. Andaya (15 September 1984). A History of Malaysia. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-38121-9.

- Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium by Ronald Findlay, Kevin H. O'Rourke p.67

- History of Asia by B. V. Rao (2005), p. 211

- Singapore in Global History by Derek Thiam Soon Heng, Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied p.40

- History Without Borders: The Making of an Asian World Region, 1000–1800 by Geoffrey C. Gunn p.43

- Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia by Hermann Kulke, K Kesavapany, Vijay Sakhuja p.71

- Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations by Tansen Sen p.226

- Aryatarangini, the Saga of the Indo-Aryans, by A. Kalyanaraman p.158

- India and Malaya Through the Ages: by S. Durai Raja Singam

- Annual Report on the Federation of Malaya: 1951 in C.C. Chin and Karl Hack, Dialogues with Chin Peng pp. 380, 81.

- Flores, Marot Nelmida-. The cattle caravans of ancient Caboloan : interior plains of Pangasinan : connecting history, culture, and commerce by cartwheel. National Historical Institute. Ermita: c2007. http://www.kunstkamera.ru/files/lib/978-5-88431-174-9/978-5-88431-174-9_20.pdf

- http://anaknabinalatongan.wixsite.com/anaknabinalatongan/single-post/2014/12/21/History-of-Binalatongan

- Scott, William Henry (1989). "Filipinos in China in 1500" (PDF). China Studies Program. De la Salle University. p. 8.

- Jovito Abellana, Aginid, Bayok sa Atong Tawarik, 1952

- http://www.asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-15-1977/francisco-indian-prespanish-philippines.pdf

- Julkarnain, Datu Albi Ahmad (30 April 2008). "Genealogy of Sultan Sharif Ul-Hashim of Sulu Sultanate". Zambo Times. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- Ibrahim 1985, p. 51

- Palawan Tabon garuda

- Hack, Karl. "Records of Ancient Links between India and Singapore". National Institute of Education, Singapore. Archived from the original on 26 April 2006. Retrieved 4 August 2006.

- "Singapore: History, Singapore 1994". Asian Studies @ University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on 23 March 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- Epigraphia Carnatica, Volume 10, Part 1, page 41

- Sar Desai, D. R. (4 December 2012). Southeast Asia: Past and Present. p. 43. ISBN 9780813348384.

- "Sri Vijaya-Malayu: Singapore and Sumatran Kingdoms". History SG.

- Victor R Savage, Brenda Yeoh (2013). Singapore Street Names: A Study of Toponymics. Marshall Cavendish. p. 381. ISBN 978-9814484749.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- C.M. Turnbull (2009). A History of Modern Singapore, 1819–2005. NUS Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-9971694302.

- Community Television Foundation of South Florida (10 January 2006). "Singapore: Relations with Malaysia". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 22 December 2006.

- "Archaeology in Singapore – Fort Canning Site". Southeast-Asian Archaeology. Archived from the original on 29 April 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2006.

- Derek Heng Thiam Soon (2002). "Reconstructing Banzu, a Fourteenth-Century Port Settlement in Singapore". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 75, No. 1 (282): 69–90.

- Paul Wheatley (1961). The Golden Khersonese: Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula before A.D. 1500. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. pp. 82–85. OCLC 504030596.

- "Hybrid Identities in the Fifteenth-Century Straits of Malacca" (PDF). Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- John Miksic (2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800. NUS Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- Baker, Jim (2008). Crossroads: A Popular History of Malaysia and Singapore. Marshall Cavendish International Asia.

- John N. Miksic (15 November 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800. NUS Press. pp. 155–163. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- John N. Miksic (15 November 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800. NUS Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- "Singapore – Precolonial Era". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 June 2006.

- John N. Miksic (2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300_1800. NUS Press. pp. 155–163. ISBN 978-9971695743.

- "Singapura as "Falsa Demora"". Singapore SG. National Library Board Singapore.

- Afonso de Albuquerque (2010). The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, Second Viceroy of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1108011549.

- Borschberg, P. (2010). The Singapore and Melaka Straits. Violence, Security and Diplomacy in the 17th century. Singapore: NUS Press. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-9971694647.

- "Country Studies: Singapore: History". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- http://www.esamskriti.com/essay-chapters/Historical-Ties-India-and-Thailand-1.aspx

External links

- Topography of Southeast Asia in detail (PDF)

- Southeast Asian Archive at the University of California, Irvine.

- "Documenting the Southeast Asian Refugee Experience", exhibit at the University of California, Irvine, Library.

- Southeast Asia Visions, a collection of historical travel narratives Cornell University Library Digital Collection

- www.southeastasia.org Official website of the ASEAN Tourism Association

- Southeast Asia Time Lapse Video Southeast Asia Time Lapse Video

- Art of Island Southeast Asia, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- A Short History of South East Asia

_VI_(1070423631).jpg.webp)

.svg.png.webp)