Inuit clothing

The traditional skin clothing of the Inuit is a complex system of cold-weather garments historically made from animal hide and fur, worn by the Inuit, a group of culturally related indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic. Despite the wide distribution of the various Inuit peoples across regions of North America and Greenland, these traditional garments are broadly consistent in both design and material, due to the common need for protection against the extreme weather of the polar regions and the limited range of materials suitable for the purpose. Production of warm, durable clothing was an essential survival skill for the Inuit, which was traditionally passed down from adult women to girls. The creation and use of skin clothing had important spiritual implications for the Inuit.

.jpg.webp)

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

.JPG.webp) |

|

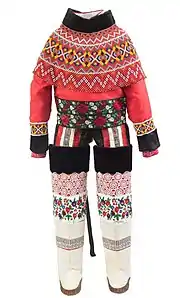

The most basic traditional outfit consisted of a coat (parka), pants, mittens, inner footwear, and outer boots made of animal hide and fur. The most common sources of hide were caribou, seals and seabirds. Clothing style varied according to gender roles and seasonal needs, as well as by the specific dress customs of each tribe or group. As a result of socialization and trade, Inuit groups incorporated clothing designs and styles from other Indigenous Arctic peoples such as the Chukchi, Koryak, and Yupik peoples of Siberia and the Russian Far East, non-Inuit North American Indigenous groups, and European and Russian traders. In the modern era, skin clothing is less common, but is still worn, often in combination with winter clothing of natural or synthetic fiber.

Traditional outfit

The most basic version of the traditional outfit consisted of a coat (parka), pants, mittens, inner footwear, and outer boots, all made of animal hide and fur. These garments were fairly lightweight despite their warmth: a complete outfit weighed no more than around 3–4.5 kg (6.6–9.9 lb) depending on the number of layers and the size of the wearer.[1] Additional layers could be added as required for the weather or activity. Although the overall framework of the outfit remained basically the same for all Inuit groups, their wide geographical range and individual cultures gave rise to a correspondingly broad range of styles for the basic garments, often unique to the region of origin. The range of distinguishing features on the parka alone was significant, as described by Inuit clothing expert Betty Kobayashi Issenman in her 1997 book Sinews of Survival, including:[2]

the hood or lack thereof, and hood shape; width and configuration of shoulders; presence of flaps front and back, and their shape; in women's clothing the size and shape of the amaut, the baby pouch; length and outline of the lower edge; and fringes, ruffs, and decorative inserts.

Tribal affinity was indicated by ornamental features such as variations in the patterns made by different colors of fur, the cut of the garment, and the length of fur.[3][4] In some cases, the styling of a garment could even indicate biographical details such as the individual's age, marital status, and specific kin group.[2] The vocabulary for describing individual garments in the numerous Inuit languages is correspondingly extensive, which Kobayashi Issenman noted in Sinews of Survival:[5]

A few examples will indicate some of the complexities: 'Akuitoq: man's parka with a slit down the front, worn traditionally in the Keewatin and Baffin Island areas'; 'Atigainaq: teenage girl's parka from the Keewatin region'; 'Hurohirkhiut: boy's parka with slit down the front'; 'Qolitsaq: man's parka from Baffin Island' (Strickler and Alookee 1988, 175).

For the sake of consistency, this article uses the Inuktitut terminology used by Kobayashi Issenman, unless otherwise noted.

| Garment name | Inuktitut syllabics[lower-alpha 1] | Description | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qulittuq | ᖁᓕᑦᑕᖅ | Closed hooded parka, fur facing out | Men's parka |

| Atigi | ᐊᑎᒋ | Closed hooded parka, fur facing in | Men's parka |

| Amauti | ᐊᒪᐅᑎ | Closed parka with pouch for infants | Women's parka |

| Qarliik | ᖃᕐᓖᒃ | Trousers | Double layered for men, single for women |

| Pualuuk | ᐳᐊᓘᒃ | Mitts | Unisex, double layered if necessary |

| Mirquliik | ᒥᕐᖁᓖᒃ[7] | Stockings | Unisex, double layered |

| Kamiit | ᑲᒦᒃ | Boots | Unisex |

| Tuqtuqutiq | ᑐᖅᑐᖁᑎᖅ | Overshoes | Unisex, worn when needed |

Upper body garments

Traditional Inuit culture divided labor by gender, so men and women wore garments specifically tailored to accommodate their distinct roles. The outer layer worn by men was called the qulittaq, and the inner layer was called the atigi.[8] These garments had no front opening, and were donned by pulling them over the head.[5] Men's coats had loose shoulders, which provided the arms with greater mobility when hunting. This also permitted a hunter to pull their arms out of the sleeves and into the coat against the body for warmth without taking the coat off. The closely fitted hood provided protection to the head without obstructing vision. The bottom hems of men's garments were cut straight.[3][9] The hem of the outer coat would be left long in the back so the hunter could sit on the back flap and remain insulated from the snowy ground while watching an ice hole while seal hunting, or while waiting out an unexpected storm.[10] A traditional parka had no pockets; articles were carried in bags or pouches. Some parkas had toggles called amakat-servik on which a pouch could be hung.[11] Men's parkas sometimes had markings on the shoulders to visually emphasize the strength of their arms.[12]

Parkas for women were called amauti and had large pouches called amaut for carrying infants.[3] Numerous regional variations of the amauti exist, but for the most part, the hem of the amauti is left longer and cut into rounded apron-like flaps, which are called kiniq in the front and akuq in the back.[13][14][9] The infant rests against the mother's bare back inside the pouch, and a belt called a qaksun-gauti is cinched around the mother's waist on the outside of the amauti, supporting the infant without restraining it.[11] At rest, the infant usually sits upright with legs bent, although standing up inside the amaut is possible.[15] The roomy garment can accommodate the child being moved to the front to breastfeed and eliminate urine and feces.[16] Women's parkas sometimes had markings on the forearms as a visual reminder of their sewing skills.[12]

Lower body garments

Both men and women wore trousers called qarliik. During the winter, men typically wore two pairs of fur pants for lengthy hunting trips, while women only needed a single layer as they usually did not go outdoors for long periods during winter.[17][18] Qarliik were waist-high and held on loosely by a drawstring. The shape and length depended on the material being used, with caribou trousers having a bell shape to capture warm air rising from the boot, and seal or polar bear trousers being generally straight-legged.[19] In some regions, particularly the Western Arctic, men, women, and children sometimes wore atartaq, leggings with attached feet similar to hose, although these are no longer common.[17][19]

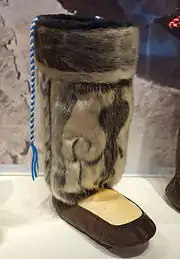

In the deepest part of winter, the traditional outfit could include up to five layers of leg coverings and footwear, depending on the weather and terrain.[20][21] Traditionally, these garments were almost always made of caribou or sealskin, although today boots are sometimes made with heavy fabric like canvas or denim.[22][23] The traditional first layer was a set of stockings called alirsiik, which had the fur facing inwards. The second was a pair of short socks called ilupirquk, and third was another set of stockings, called pinirait; both of which had outward-facing fur. The fourth layer was the boots, called kamiit or mukluks.[lower-alpha 2] These could be covered with the tuqtuqutiq, a kind of short, thick-soled overshoe that provided additional insulation to the feet.[20] These overshoes could be worn indoors as slippers while the kamiit were drying out.[25]

During the wet season of summer, waterproof boots were worn instead of insulating fur boots. These were usually made of sealskin with the fur removed. To provide grip on icy ground, boot soles could be pleated, or sewn with strips of dehaired seal skin.[20][26] Boot height varied depending on the task – sealskin boots could be made thigh-high or even chest-high if they were to be used for wading into water, similar to modern hip boots or waders.[22] Boots intended for use in wet conditions sometimes included drawstring closures at the top to keep water out.[27] In modern times, boot tops made of skin may be sewn to mass-produced rubber boot bottoms to create a boot that has the warmth of skin clothing with the waterproofing and grip of artificial materials. These are useful for fishermen and people foraging for sea urchins and sea cucumbers.[28]

Accessory garments

Most upper garments included a built-in hood, but some groups like the Kalaallit of Greenland wore separate hats instead, in a similar fashion to the Yupik peoples of Siberia. Many Canadian Inuit wear a cap beneath their hood for additional insulation during winter. During summer, when the weather is warmer and mosquitoes are in season, the hood is not used; instead, the cap is draped with a scarf which covers the neck and face to provide protection from insects.[29]

Inuit mitts are called pualuuk, and are usually worn in a single layer. If necessary, two layers can be used, but this reduces dexterity. Most mitts are caribou skin, but sealskin is used for work in wet conditions, while bear is preferred for icing sled runners as it does not shed when damp. The surface of the palm can be made of skin with the fur removed to increase the grip. Sometimes a cord was attached to the mitts and worn across the shoulders, preventing them from being lost.[30]

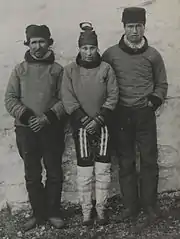

Children's clothing

Children's clothing was similar in form and function to adult clothing, but typically made of softer materials like caribou fawn, fox skin, or rabbit. Once children were old enough to walk, they would wear a one-piece suit called an atajuq, similar in form to a modern blanket sleeper. This garment had attached feet and often mittens as well, and unlike an adult's parka, it opened at the front. Older children wore outfits with separate parkas and trousers like adults.[31]

Amautis for female children had amaut, and they sometimes carried younger siblings in them to assist their mother.[32] Clothing for girls changed at puberty. Amauti tails were made longer, and the hood and amaut were enlarged. Hairstyles for pubescent girls also changed to indicate their new status.[33]

Materials

The most common sources of hide for Inuit clothing are caribou and seals, with caribou being preferred for general use.[8][34][35] Historically, seabirds were also an important source for clothing material, but use of seabird skins is now rare even in places where traditional clothing is still common.[36] Less commonly used sources included wolverines, wolves, musk-oxen, bears, foxes, ground squirrels, marmots, moose, whales, and muskrats. The use of these animals depended on location and season.[37][38] Today, commercially prepared cowhide or sheepskin may also be used by some seamstresses.[39]

Regardless of the source, the Inuit traditionally used as much of the animal as possible. Tendons and other membranes were used to make tough, durable fibers, called sinew thread or ivalu, for sewing clothing together. Feathers were used for decoration. Rigid parts like bones, beaks, teeth, claws, and antlers were carved into tools or decorative items.[37] Intestine from seals and walruses was used to make waterproof jackets for rain.[14] The soft material shed from antlers, known as velvet, was used for tying back hair.[37]

Caribou and seal

The hide of the barren-ground caribou, an Arctic subspecies of caribou, was the most important source of material for clothing of all kinds, as it was readily available, versatile, and, when left with the fur intact, very warm.[40] Caribou fur grows in two layers, which trap air, which is then warmed up by body heat. The skin itself is thin and supple, making it light and flexible.[37] Each piece of the hide had qualities that made it suitable for various uses: for example, the tough leg skins were used for items that required durability.[41] Caribou sheds badly when exposed to moisture, so it is not suitable for wet-weather garments.[42] Caribou hide could also be shaved and used for footwear and decorative fringe.[43]

The hide of Arctic-dwelling seals is both lightweight and water repellant, making it ideal as single-layer clothing for the wet weather of summer. Year-round, it was used to make clothing for water-based activities like kayaking and fishing, as well as for boots and mittens.[14] Seal hide is porous enough to allow sweat to evaporate, making it ideal for use as boots. Of the four Arctic seals, the ringed seal and the bearded seal are the most commonly used for skin clothing, as they have a large population and are widely distributed. Harbour seals have a wide distribution but lower population, so they are less commonly used. Clothing made from harp seals has been reported, but documentation is lacking.[44] The skin of younger seals killed in autumn is traditionally preferred for aesthetic reasons, as it is darker and less likely to be damaged.[35]

Other animal sources

Like caribou fur, polar bear fur grows in dual layers, and is prized for its heat-trapping and water-resistant properties. The long guard hairs of dogs, wolves, and wolverines were preferred as trim for hoods and mittens.[45] The fur of arctic foxes was sometimes also used for trim, and was suitable for hunting caps and the insides of socks. In some areas, women's clothing was made of fox hides, and it was used to keep the breasts warm during breastfeeding. Adult musk-ox hide is too heavy to be used for most clothing, but it was used for mittens as well as summer caps, as the long hairs kept mosquitoes away. It was also suitable as bedding.[46][42] In modern times, wool made from musk-ox down is sold commercially. The skins of small animals like marmots and Arctic ground squirrels are used for upper garments and decorations.[42]

The skin of cetaceans like beluga whales and narwhals was sometimes used for boot soles.[43] Whale sinew, especially from the narwhal, was prized as thread for its length and strength. Tusks from narwhal and walrus provided ivory, which was used for sewing tools, clothing fasteners, and ornaments. In Alaska, fish skins were sometimes used for clothing and bags, but this is not well-documented in Canada.[47]

The use of bird skins, including eider duck, auk, cormorant, guillemot, ptarmigan, loon, puffin, swan, and goose, has been documented by all Inuit groups. The skin, feet, and bones were used to make clothing of all kinds, as well as tools, containers, and decorations.[47] Historically, eider duck was most heavily used by the Inuit of the Belcher Islands in Hudson Bay, as there were no caribou on the islands.[48]

Construction and maintenance

Women were responsible for all stages of producing clothing, from preparation of skins to the sewing of garments. These skills have historically been passed from grandmothers and mothers to their daughters and grandchildren, beginning in childhood. Fully mastering them could take until a woman was into her mid-thirties.[3][49] Learning to make traditional clothing is typically a process of acquiring tacit knowledge by observing and learning the sewing process, then creating items independently, without explicit verbal directions.[50] It was essential for garments to be sewn well and properly maintained, as drafty clothing could lead to frostbite, which in extreme cases can result in the amputation of limbs.[51]

Preparation of new items occurred on a yearly cycle that typically began after the traditional hunting seasons. Caribou were hunted in the autumn from approximately August to October, and sea mammals like seals were hunted from December to May. Production of clothing was an intensive communal process undertaken by entire families gathered together. The sewing period following hunting could last for up to four weeks.[52] It could take up to 300 hours just to prepare the caribou hides necessary for a five-member family to each have two sets of clothing, and another 225 hours to cut and sew the garments from them.[53][54]

Tools

Inuit seamstresses traditionally used tools handcrafted from animal materials like bones, antlers, baleen, and ivory, including the ulu knife, needle, awl, thimble and thimble-guard, and a needlecase.[40][14] Ulu knives were particularly important tools for seamstresses, and were often buried with their owner at her death.[55] Wood and stone were often used for ulu, and when available, meteoric iron or copper was cold worked into blades by a process of hammering, folding, and filing.[56][52]

After contact with Western explorers, the Inuit began to make use of sheet tin, brass, non-meteoric iron, and even steel, obtained by trading or scrapping.[52] They also adopted steel sewing needles, which were more durable than bone needles.[57] European contact also brought scissors to the Inuit, but they were not widely adopted, as they do not cut furry hides as cleanly as sharp knives.[58] Traditionally, Inuit seamstresses used thread made from sinew, called ivalu. Modern seamstresses generally use thread made from linen, cotton, or synthetic fibers, which are easier to find and less difficult to work with, although these materials are less waterproof compared to ivalu.[59][60]

Hide processing

.jpg.webp)

The first stage was the harvesting of the skin from the animal carcass after a successful hunt. Generally, the hunter would cut the skin in such a way that it could be removed in one piece. Skinning and butchering an adult caribou could take an experienced hunter up to an hour.[61] While butchering of caribou was handled by men, butchering of seals was mostly handled by women.[62]

After the skin was removed, the hides would be dried on wooden frames, then laid on a scraping platform and scraped of fat and other tissues with an ulu knife until soft and pliable.[40][63][64] Most skins, including bird skins, were processed in roughly the same way, although processing oily skins like sealskin and sometimes polar bear skin required the additional step of degreasing the hide by washing it with soap or dragging it across gravel.[65][66] If the hide was soiled with blood, rubbing with snow or soaking in cold water could remove the stain.[67] Sometimes the fur would need to be removed so the hide could be used for things like boot soles, which could be done with an ulu, or if the hair had been loosened by putrefaction or soaking in water, a blunt scraping tool could also suffice.[63] The hide would be chewed, rubbed, wrung up, soaked in liquid, and even stamped on to soften it further for sewing.[68][69] The softening process was repeated until the women judged the skin was ready. Badly processed hides would stiffen or rot, so correct preparation of hides was essential to ensure the quality of the clothing.[53]

Sewing of garments

When the hide was ready, the process of creating each piece could begin. The first step was measuring, a detailed process given that each garment was tailored for the wearer. No standardized sewing pattern was used, although older garments were sometimes used as models for new ones.[3] Traditionally, measurement was done by eye and by hand alone, although some seamstresses now make bespoke paper patterns following a hand and eye measurement process.[25][23] The skins were then marked for cutting, traditionally by biting or pinching, or with an edged tool, although in modern times ink pens may be used. The direction of the fur flow is taken into account when marking the outline of the pieces. Most garments were sewn with fur flowing from top to bottom, but strips used for trim had a horizontal flow for added strength.[70] Once marked, the pieces of each garment would be cut out using the ulu, taking care not to stretch the skin or damage the fur. Adjustments were made to the pattern during the cutting process as need dictated. The marking and cutting process for a single amauti could take an experienced seamstress an entire hour.[71]

Once the seamstress was satisfied that each piece was the appropriate size and shape, the pieces were sewn together to make the complete garment. Tight, high-quality seams was essential to prevent cold air and moisture from entering the garment.[51] Four main stitches were used, from most to least common: the overcast stitch, the tuck or gathering stitch, the running stitch, and the waterproof stitch, a uniquely Inuit development.[71][72] The overcast stitch was used for the seams of most items. The tuck or gathering stitch was used to join pieces of uneven size. The running stitch was used to attach facings or insert material of a contrasting color. Betty Kobayashi Issenman described the waterproof stitch, or ilujjiniq, as being "unequalled in the annals of needlework."[73] Two lines of stitching made up one waterproof seam, which were mostly employed on boots and mitts. On the first line, the needle pierced partway through the first skin, but entirely through the second; this process was reversed on the second line, creating a seam in which the needle and thread never fully punctured both skins at the same time. Ivalu swells with moisture, filling the needle holes and making the seam waterproof.[74]

Maintenance

Once created, Inuit skin clothing must be properly maintained, or it will become brittle, lose hair, or even rot. Warmth and moisture are the biggest risks to clothing, as they promote the growth of decay-inducing bacteria. If the garment is soiled with grease or blood, the stain must be rubbed with snow and beaten out quickly.[75] In addition to practical considerations, wearing clean clothing on a hunt was important, because it was considered a sign of respect for the spirits of the animals.[76]

Historically, the Inuit used two main tools to keep their garments dry and cold. The tiluqtut, or snow beater, was a rigid implement made of bone, ivory, or wood. It was used to beat the snow and ice from clothing prior to entering the home. Once inside the home, the garments were laid over a drying rack near a heat source so they could be dried slowly. All clothing, especially footwear, was checked daily for damage and repaired immediately if any was discovered. Boots were chewed, stretched, or rubbed across a boot softener to maintain durability and comfort.[75][77] Although women were primarily responsible for sewing new garments, both men and women were taught to repair clothing and carried sewing kits while travelling for emergency repairs.[68]

Major principles

Inuit clothing expert Betty Kobayashi Issenman identified five key aspects common to all Inuit skin clothing, made necessary by the challenges particular to the polar environment.[78]

- Insulation and heat conservation: Clothing worn in the Arctic must be warm, especially during the winter, when the polar night phenomenon means the sun never rises and temperatures can drop below −40 °C (−40 °F) for weeks or even months.[79] Inuit garments were designed to provide thermal insulation for the wearer in several ways. Caribou fur is an excellent insulating material: the hollow structure of caribou hairs helps trap warmth within individual hairs, and the air trapped between hairs also retains heat. Each garment was individually tailored to the wearer's body with complex tailoring techniques including darts, gussets, gathers, and pleats.[1] Openings were minimized to prevent unwanted heat loss, but in the event of overheating, the hood could be loosed to allow heat to escape.[80] Layers were structured to reduce drafts between overlapping pieces.[81] For the warmer weather of spring and summer, only a single layer of clothing was necessary. Both men and women wore two upper-body layers during the harsher temperatures of winter. The inner layer had fur on the inside against the skin for warmth, and the outer layer had fur facing outward.[3][14]

- Humidity and temperature control: Perspiration, no matter how slight, eventually leads to the accumulation of moisture in closed garments. Materials used for Inuit clothing had to allow for efficient management of the resulting moisture. Fibres like wool are not suitable, as they will absorb the moisture directly and hold it against the skin. If the temperature is too low, moisture will condense into frost, which can cause life-threatening heat loss unless the garment is removed. In contrast, fur does not absorb moisture, and when frost forms on it, it can be brushed away, since it is not directly absorbed into the individual hairs. Since the frost can be brushed away, the garment also does not need to be dried by an exterior heat source.[10][82] Long, uneven hair from wolves, dogs, or wolverines was used to trim each hood, collecting moisture from breath and allowing it to be brushed away after it crystallized. This fur ruff also reduces wind velocity on the face.[82] The individual fit of each garment also contributed to humidity control, as the careful tailoring allowed air to circulate between the body and the clothing, keeping the body dry.[10] For footwear, animal skin provides greater condensation control than nonporous materials like rubber or plastic, as it allows moisture to escape, keeping the feet drier and warmer for longer.[22]

- Waterproofing: Making garments waterproof was a major concern for Inuit peoples, especially during the wetter weather of summer. The skin of marine mammals like seals sheds water naturally, but is lightweight and breathable, making it extremely useful for this kind of clothing. Prior to the availability of artificial waterproof materials, seal or walrus intestine was commonly used to make raincoats and other wet-weather gear. Skillful sewing using sinews allowed the creation of waterproof seams, particularly useful for footwear.[10]

- Functional form: Garments were tailored to be practical and to allow the wearer to perform their work efficiently. As the Inuit peoples traditionally divided labor by gender, clothes were tailored in distinct styles for men and women. A man's coat meant to be worn while hunting, for example, would have shoulders tailored with extra room to provide unrestricted movement, while also allowing the wearer to pull their arms into the garment and close to the body for warmth.[81] The women's coat, the amauti, was tailored to include a large back pouch for carrying infants.[83]

- Durability: Inuit clothing needed to be extremely durable. Most people only had one set of clothing, and since the creation of skin clothing was a labour-intensive, highly customized process, with base materials available only seasonally depending on the source animal, badly damaged garments were not easy to replace.[40][80] Due to the value of furs, old or worn-out skin clothing was historically not discarded at the end of the season. Instead, it was repurposed as bedding or work clothing, or taken apart and used to repair newer garments.[84] To increase durability, seams were placed to minimize stress to the skins.[81] For example, the shoulder seam is dropped off the shoulder, and the side seams are placed off center.[75] Different cuts of skin were used according to their individual qualities - hardier skin from the animal's legs was used for mitts and boots, which required toughness, while more elastic skin from the animal's shoulder would be used for a jacket's shoulder, which required flexibility.[85] The use of fasteners and closures was minimized to reduce the need for maintenance.[81] Rips or tears would compromise the garment's ability to retain heat and regulate humidity, so they were repaired as soon as possible. Hunters carried sewing kits which enabled them to make repairs in the field if necessary.[85][81]

Aesthetics

Historically, the Inuit have added visual appeal to their clothing with trim and inlays, color contrast, decorative attachments, and design motifs, integrating and adapting new techniques and materials as they were introduced by cultural contact.[86]

Trim and inlays were made visually appealing with variations in fur direction, length, texture, and color. Dehaired skin was sometimes used decoratively, as in the Labrador Inuit use of scalloped trim on boots.[87] Textile materials such as braid, rickrack, and bias tape were adopted as they became available.[88][89] One traditional Inuit trim style is called qupuk trim or delta trim, which consists of small strips of fabric (usually bias tape) sewn together to make geometric patterns.[90][91] The Kalaallit of Greenland are particularly known for a decorative trim known as avittat, or skin embroidery, in which tiny pieces of dyed skin are appliquéd into a mosaic so delicate it resembles embroidery.[92] While somewhat visually similar, it is unclear if qupak and avittat are related techniques.[93] Another Kalaallit technique, slit weaving, involves a strip of hide being woven through a series of slits in a larger piece of a contrasting color, producing a checkered pattern.[92]

Some skins were colored or bleached. Dye was used to color both skins and fur. Shades of red, black, brown, and yellow were made from minerals such as ochre and galena, obtained from crushed rocks and mixed with seal oil.[94][63] Plant-based dyes were available in some areas as well. Alder bark provided a red-brown shade, and spruce produced red.[63] Lichen, moss, berries, and pond algae were also used.[92] In modern times, some Inuit use commercial fabric dye.[63] Skins could also be tanned with smoke to make them brown, or left outside in the sun to bleach them white.[43]

Many Inuit groups used attachments like fringes, pendants, and beads to decorate their garments. Fringing on caribou garments was practical as well, as it could be interlocked between layers to prevent wind from entering. The paw skins from animals like wolves and wolverines were sometimes hung decoratively from men's belts.[95] Pendants were made from all kinds of materials. Traditionally soapstone, animal bone, and teeth were the most prevalent, but after European contact, items like coins, bullet casings, and even spoons were used as decorations.[17][96]

Beadwork was generally reserved for women's clothing. Before European contact, beads were made from amber, stone, tooth, and ivory. European traders brought colorful glass beads that were highly prized, and could be traded for other valuables. The Hudson's Bay Company was the largest trader of beads to the Inuit, trading strings of small seed beads in large batches, as well as more valuable beads such as the Venetian-made Cornaline d'Aleppo, which were red with a white core. Sections of strung seed beads were used as fringe or stitched directly onto the hide. Some beadwork was applied to panels of skin, which could be removed from an old garment and sewn onto a new one; such panels were sometimes passed down through families.[97] Modern seamstresses sometimes purchase premade beaded pieces from fabric stores.[88]

Inuit clothing makes heavy use of motifs, which are figures or patterns incorporated into the overall design of the garment. In traditional skin clothing, these are added with contrasting inserts, beadwork, embroidery, appliqué, or dyeing. The roots of these designs can be traced back to the Paleolithic era through artifacts which use basic forms like triangles and circled dots.[98] Later forms were more complex and highly varied, including scrolls and curlicues, heart shapes, and even plant motifs.[99] Beginning in the 1950s and 1960s, the designs on fur inserts used for kamiit became increasingly elaborate, and by the 1980s were incorporating designs drawn from modern culture. Jill Oakes and Rick Riewe describe the variety: "a larger number of intricate insets were used, including animals, flowers, logos, letters, hockey team names, people's names, community names, snowmobile brand names, and political concerns."[100]

Clothing as an expression of spirituality

The entire process of creating and wearing traditional clothing was intimately connected with Inuit spiritual beliefs. Hunting was seen as a sacred act.[102] It was important for people to show respect and gratitude to the animals they killed, to ensure that they would return for the next hunting season. Specific practices varied depending on the animal being hunted and the particular Inuit group. Wearing clean, well-made clothing while hunting was important, because it was considered a sign of respect for the spirits of the animals. Some groups left small offerings at the site of the kill, while others thanked the animal's spirit directly. Generous sharing of the meat from a hunt pleased the animal's spirit and showed gratitude for its generosity.[102] It was believed that the spirits of polar bears remained within the skin after death for several days. When these skins were hung up to dry, desirable tools were hung around them. When the bear's spirit departed, it took the spirits of the tools with it and used them in the afterlife.[76]

For many Inuit groups, the timing of sewing was governed by spiritual considerations. Traditionally, women never began the sewing process until hunting was completely finished, to allow the entire community to focus exclusively on the hunt.[103] The goddess Sedna, mistress of the ocean and the animals within, disliked caribou, so it was taboo to sew sealskin clothing at the same time as caribou clothing. Production of sealskin clothing had to be completed in the spring before the caribou hunt, and caribou clothing had to be completed in fall before the time for hunting seal and walrus.[104]

Wearing skin clothing traditionally created a spiritual connection between the wearer and the animals whose skins are used to make the garments. This pleased the animal's spirit, and in return it would return to be hunted in the next season. It was also thought to impart the wearer with the animal's characteristics, like endurance, speed, and protection from cold. Shaping the garment to resemble the animal enhanced this connection. For example, the animal's ears were often left on parka hoods, and contrasting patterns of light and dark fur were placed to emulate the animal's natural markings.[105] Some researchers have theorized that these light and dark patterns may represent the animal's bones.[105] The Copper Inuit used a design mimicking a wolf's tail on the back of their parkas, referencing the natural predator of the caribou.[106]

Amulets made of skin and animal parts were worn for protection and luck, and to invest the wearer with the animal's powers. Hunters might wear a pair of tiny model boots while out hunting to ensure that their own boots would last. Weasel skins sewn to the back of the parka provided speed and cleverness.[107] The rattling of ornaments like bird beaks was thought to drive off evil spirits.[108]

Ceremonial clothing

In addition to their everyday clothing, many Inuit had a set of ceremonial clothing made of short-haired summer skins, worn for dancing or other ceremonial occasions. In particular, the dance clothing of the Copper Inuit, a Canadian Inuit group from the territory of Nunavut, has been extensively studied and preserved in museums worldwide.[109] Dance clothing was generally not hooded; instead, special dancing caps were worn. These dancing caps were often intricately sewn with stripes and other decorations. The Copper Inuit sewed the beaks of birds like loons and thick-billed murres to the crown of their caps, invoking the vision and speed of the animals.[110] Traditional ceremonial clothing also incorporated masks made of wood and skin, although this practice largely died out after the arrival of missionaries and other outsiders.[111]

Inuit shamans, called angakkuq,[lower-alpha 3] often had distinct clothing such as headdresses and belts that differentiated them from laypeople. Masks could be worn to invoke supernatural abilities, and unique head coverings, particularly of birdskin, provided a sense of power during spiritual rituals.[113] The use of stoat skins for a shaman's clothing invoked the animal's intellect and cunning.[114] The fur used for a shaman's belt was white, and the belts themselves were adorned with amulets and tools, often representative of important events in the shaman's life.[113][115] Mittens and gloves, though not visually distinct, were important components of shamanic rituals.[116]

Gender expression

Inuit clothing was traditionally tailored in distinct styles for men and women, but there is evidence from oral tradition and archaeological findings that biological sex and gendered clothing was not always aligned.[83][117] Some shamanic clothing for men, particularly among the Copper Inuit, included design elements generally reserved for women, such as frontal apron-flaps or kiniq, symbolically bringing male and female together.[118] In some cases, the gender identity of the shaman could be fluid or non-binary, which was reflected in their clothing through the use of both male and female design elements.[112]

In some areas of the Canadian Arctic, such as Igloolik and Nunavik, there was historically a third gender identity known as sipiniq[lower-alpha 4] ("one who had changed its sex").[120] People who were born sipiniq were believed to have changed their physical sex at the moment of birth, primarily from male to female (although the reverse could occur, very rarely).[121] Female-bodied sipiniit were socially regarded as male, and would be named after a deceased male relative, perform a male's tasks, and would wear clothing tailored for such tasks.[120] Kobayashi Issenman regarded this as a spiritual practice whereby the child incorporated the spirit of the deceased relative, rather than an expression of the child being transgender.[119]

History

Prehistoric development

Individual skin garments are rarely found intact, as animal hide is susceptible to decay. Evidence for the historic consistency of traditional Inuit clothing is usually inferred from sewing tools and art objects found at archaeological sites.[122] In what is now Irkutsk Oblast, Russia, archaeologists have found carved figurines and statuettes at sites originating from the Mal'ta–Buret' culture which appear to be wearing tailored skin garments, although these interpretations have been contested. The age of these figurines indicates that, if the interpretations are correct, Inuit skin clothing may have originated as early as 24,000 years ago.[123] Tools for skin preparation and sewing made from stone, bone, and ivory, found at prehistoric archaeological sites, confirm that skin clothing was being produced in northern regions as early as 2500 BCE.[124] Archaeological evidence of seal processing by the Dorset culture, a Paleo-Inuit culture, has been found at Philip's Garden in the Port au Choix Archaeological Site in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. Radiocarbon dating indicates the site spanned approximately eight centuries, from about 50 BCE at the earliest to about 770 CE at the latest.[lower-alpha 5][125]

Occasionally, scraps of frozen skin garments or even whole garments are found at archaeological sites. Some of these items come from the Dorset culture era of approximately 500 BCE to 1500 CE, but the majority are from the Thule culture era of approximately 1000 to 1600 CE.[126][127] Although some style elements like hood height and flap size have changed, structural elements like patterns, seams, and stitching of these remnants and outfits are very similar to garments from the 17th to mid-20th centuries, which confirms significant consistency in construction of Inuit clothing over centuries.[128][129][127]

In 1972, a group of eight well-preserved and fully dressed mummies were found at Qilakitsoq, an archaeological site on Nuussuaq Peninsula, Greenland. They have been carbon-dated to c. 1475, and analysis indicates that the garments were prepared and sewn in the same manner as modern skin clothing from the Kalaallit people of the region.[130] Archaeological digs in Utqiagvik, Alaska from 1981 to 1983 uncovered the earliest known samples of clothing of the Kakligmiut people, carbon-dated to c. 1510. The construction of these garments indicates that Kakligmiut garments underwent little change between approximately 1500–1850.[131]

As a result of socialization and trade, Inuit groups throughout their history incorporated clothing designs and styles between themselves, as well as from other Indigenous Arctic peoples such as the Chukchi, Koryak, and Yupik peoples of Siberia and the Russian Far East, the Sámi people of Scandinavia, and various non-Inuit North American Indigenous groups.[2][132] There is evidence indicating that prehistoric and historic Inuit gathered in large trade fairs to exchange materials and finished goods; the trade network that supported these fairs extended across some 3,000 km (1,900 mi) of Arctic territory.[133]

Post-European contact

A 1654 painting by Salomon von Hauen, commissioned at Bergen, is the oldest known portrait depicting Kalaallit people in traditional clothing. It shows a group of four Kalaallit who were kidnapped by a Danish trade ship. Each is shown wearing traditional skin clothing similar to that found with the bodies at Qilakitsoq.[134]

Beginning in the 1700s, contact with non-Inuit, including American, European, and Russian traders and explorers, began to have a greater influence on the construction and appearance of Inuit clothing.[2] These people brought trade goods such as metal tools, beads, and fabric which began to be integrated into traditional clothing.[135][131] For example, imported duffel cloth was useful for boot and mitt liners.[136]

It is important to note that these new materials, tools, and techniques generally did not alter the basic structure of the traditional skin clothing system, the basic composition of which has always remained consistent. In many cases the Inuit were dismissive of so-called "white men's clothing"; the Inuvialuit referred to cloth pants as kam'-mik-hluk, meaning "makeshift pants".[137] The Inuit selectively adopted foreign elements that simplified the construction process (such as metal needles) or aesthetically modified the appearance of garments (such as seed beads and dyed cloth), while rejecting elements that were detrimental (such as metal fasteners, which may freeze and snag, and synthetic fabrics, which absorb perspiration).[57][136][137][138][139]

European and American clothing never fully replaced the traditional clothing complex of the Inuit, but it did gain a certain degree of traction in some areas. Sometimes this was not by choice, as in the cases of Labrador, Canada, and Kaktovik, Alaska, where Christian missionaries in the 18th century insisted that Inuit women wear foreign garments such as long skirts or dresses to religious services because Inuit garments were seen as inappropriate.[136][140] Following the 1783 establishment of a Russian trading post on Kodiak Island in what is now Alaska, use of sea otter and bear pelts for traditional garments was restricted, because the Russians preferred to sell the valuable pelts internationally.[139]

In other cases, the Inuit adopted these garments themselves. They made use of ready-made clothing and shawls sold by the Hudson's Bay Company.[141] Nunavimiut men adopted crocheted woolen hats for beneath their hoods.[137] In 1914, the arrival of the Canadian Arctic Expedition in the territory of the previously-isolated Copper Inuit prompted the virtual disappearance of the unique Copper Inuit clothing style, which by 1930 was almost entirely replaced by a combination of styles imported by newly-immigrated Inuvialuit and European-Canadian clothing such as the Mother Hubbard dress.[142]

Decline and present day revitalization efforts

.jpg.webp)

The production of traditional skin garments for everyday use has declined in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as a result of loss of skills combined with shrinking demand. The introduction of the Canadian Indian residential school system to northern Canada, beginning with the establishment of Christian mission schools in the 1860s, was extremely destructive to the ongoing cycle of elders passing down knowledge to younger generations through informal means.[143][144] Children who were sent to residential schools or stayed at hostels to attend school outside their communities were often separated from their families for years, in an environment that made little to no attempt to include their language, culture, or traditional skills.[145] Children who lived at home and attended day schools were at school for long hours most days, leaving little time for families to teach them traditional clothing-making and survival skills.[146] Until very recently, day schools did not include material on Inuit culture, compounding the cultural loss.[147] The time available for traditional skills was further reduced in areas of significant Christian influence, as Sundays were seen as a day of rest on which to attend church services, not to work.[148] Lacking the time and inclination to practice, many younger people lost interest in creating traditional clothing.[148]

Shrinking demand has also been a factor in the decline of skin clothing. The advent of indoor heating makes insulated indoor clothing less vital. Many Inuit work outdoor jobs for which fur clothing would be impractical. Purchasing manufactured clothing saves time and energy, and it can be easier to maintain than traditional skin clothing.[149] The availability of pelts also impacted the production of skin garments. In the early 20th century, overhunting led to a significant depletion of caribou herds in some areas.[150] Starting in the 1980s, opposition to seal hunting from the animal rights movement led to a major decline in the export market for seal pelts, and a corresponding drop in hunting as a primary occupation.[151][148] The combination of these various factors resulted less demand for elders to create skin garments, which made it less likely that they would pass on their skills.[147] By the mid-1990s, the skills necessary to make Inuit skin clothing were in danger of being completely lost.[152]

Since that time, Inuit groups have made significant efforts to preserve traditional skills and reintroduce them to younger generations in a way that is practical for the modern world. By the 1990s, both the residential schools and the hostel system in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories[lower-alpha 6] had been abolished entirely.[153] In northern Canada, many schools at all stages of education have now introduced courses which teach traditional skills and cultural material.[154] Outside of the formal education system, cultural literacy programs such as Miqqut, Somebody's Daughter, Reclaiming our Sinew, and Traditional Skills Workshop, spearheaded by organizations like Pauktuutit (Inuit Women of Canada) and Ilitaqsiniq (Nunavut Literacy Council), have been successful in reintroducing modern Inuit to traditional clothing-making skills.[155][156] Modern-day techniques, such as the use of wringer washing machines to soften hides and the application of Mr. Clean all-purpose cleaner to produce soft white leather, ease the time and effort needed for production, making the work more attractive.[148] Prepared skins are also available at some northern supply stores today, allowing seamstresses to shop directly for their desired materials.[35] Modern Inuit clothing has been studied as an example of sustainable fashion and vernacular design.[157][158]

Although full outfits of traditional skin clothing are now much less commonly worn, fur boots, coats and mittens are still popular, and skin clothing is particularly preferred for winter wear, especially for Inuit people who still make their living hunting and trapping.[151] Traditional skin clothing is also preferred for special occasions like drum dances, weddings, and holiday festivities.[159] Even garments made from woven or synthetic fabric today adhere to ancient forms and styles in a way that makes them simultaneously traditional and contemporary.[140][160] Much of the clothing worn today by Inuit dwelling in the Arctic has been described as "a blend of tradition and modernity."[149] Kobayashi Issenman describes the continued use of traditional fur clothing as not simply a matter of practicality, but "a visual symbol of one's origin as a member of a dynamic and prestigious society whose roots extend into antiquity."[149]

Research on Inuit clothing

History and anthropology

Inuit skin clothing has long been of academic interest to historians and anthropologists. Ethnographers such as John Murdoch published descriptions of Inuit clothing with detailed illustrations as early as 1892, based on fieldwork in northwest Alaska.[161] The 1914 dissertation of Danish archaeologist Gudmund Hatt based his theory of Inuit origins on a study of Inuit clothing in museums across Europe.[162] Later scholarship disputed his migration theory, but his studies of Inuit clothing, with their elaborate images drawn by his wife Emilie Demant Hatt, have been described as "groundbreaking in their meticulousness and scope".[162] Although his style of grand cross-cultural study has fallen out of the mainstream, scholars have continued to make in-depth studies of the clothing of various Inuit and Arctic groups.[163]

Many museums have extensive collections of historical Inuit garments. The collection of the National Museum of Denmark contains over 2100 historic skin clothing items from various Arctic cultures, with examples collected and donated as early as 1830.[164] In 1851, Finnish ethnographer Henrik Johan Holmberg acquired several hundred artifacts, including skin garments, from the Alaskan Inuit and the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, which were acquired by the National Museum in 1852.[165] Noted anthropological expeditions such as the Gjøa Expedition (1903–1906) and the Fifth Thüle Expedition (1921–1924) brought back and donated to the museum a combined total of over 800 North American Inuit garments.[166] The ceremonial dance clothing of the Copper Inuit is also well-represented in museums worldwide.[114] In 2001, the British Museum in London presented Annuraaq, an exhibition of Inuit clothing.[167]

Collaborations between scholars and Inuit people and communities have been important for the preservation of traditional knowledge. In the 1980s, Inuit clothing expert Bernadette Driscoll Engelstad travelled to museums in Europe and Canada with Inuit seamstresses to study historical garments. Their work has been credited with having "triggered a renaissance in clothing manufacture in some Canadian communities."[168] Around the same time, Arctic anthropologist Susan Kaplan began to work with North Greenland Inuit and Labrador Inuit at the Peary–MacMillan Arctic Museum on similar fieldwork.[168]

Collaborative projects such as Skin Clothing Online, from the National Museum of Denmark, Greenland National Museum, and Museum of Cultural History, Oslo, have made thousands of high-resolution images and dozens of 3D scans of hundreds of pieces of skin clothing from various Arctic cultures freely accessible to researchers and the general public.[164][169][170]

Studies of effectiveness

Another significant area of research on Inuit skin clothing has been its effectiveness, especially as contrasted with modern winter clothing made from synthetic materials. Despite significant oral testimony from Inuit elders on the effectiveness of caribou-skin garments, little direct research was performed on the topic until the 1990s.[171] A study published in 1995 compared caribou-skin clothing to mass-produced military and expedition gear, and found that the Inuit garments were significantly warmer, and provided a greater degree of perceived comfort than the mass-produced items.[172] Further studies have shown that the traditional Inuit fur ruff is the most efficient system for preventing heat transfer from the face.[173]

Inuit clothing and the fashion industry

The intersection between traditional Inuit clothing and the modern fashion industry has often been contentious. Inuit seamstresses and designers have described instances of non-Inuit designers making use of traditional Inuit design motifs and clothing styles without obtaining permission or giving credit. In some cases, the designers have altered the original Inuit design in a way that distorts its cultural context, but continue to label the product as authentic.[174] Inuit designers have criticized this practice as cultural appropriation.[175][176]

In 1999, American designer Donna Karan of DKNY sent representatives to the western Arctic to purchase traditional garments, including amauti, to use as inspiration for an upcoming collection.[176][177] Her representatives did not disclose the purpose of their visit to the local Inuit, who only became aware of the nature of the visit after a journalist contacted Inuit women's group Pauktuutit seeking comment. Pauktuutit described the company's actions as exploitative, stating "the fashion house took advantage of some of the less-educated people who did not know their rights."[174] The items they purchased were displayed at the company's New York boutique, which Pauktuutit believed was done without the knowledge or consent of the original seamstresses.[178] After a successful letter-writing campaign organized by Pauktuuit, DKNY cancelled the proposed collection.[176][177]

In 2015, London-based design house KTZ released a collection which included a number of Inuit-inspired garments. Of particular note was a sweater with designs taken directly from historical photographs of a Inuit shaman's unique parka.[179][180] The shaman, Ava, designed the parka in the 1920s, and various stories exist to explain its intricate designs.[179] Bernadette Driscoll Engelstad has described the parka as "the most unique garment known to have been created in the Canadian Arctic."[180] Ava's great-grandchildren criticized KTZ for failing to obtain permission to use the design from his family.[179] After the criticism was picked up by the media, KTZ issued an apology and pulled the item.[181]

Some brands have made efforts to work with Inuit designers directly. In 2019, Canadian winterwear brand Canada Goose launched Project Atigi, commissioning fourteen Canadian Inuit seamstresses to each design a unique parka or amauti from materials provided by Canada Goose. The designers retained the rights to their designs. The parkas were displayed in New York City and Paris before being sold, and the proceeds, which amounted to approximately $80,000, were donated to national Inuit organization Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK).[182][183] The following year, the company released an expanded collection called Atigi 2.0, which involved eighteen seamstresses who produced a total of ninety parkas. The proceeds from the sales were again donated to ITK. Gavin Thompson, vice-president of corporate citizenship for Canada Goose told CBC that the brand had plans to continue expanding the project in the future.[183]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Inuit hunter wearing cloth garments, bringing caribou skins back to camp at Koukdjuak, Nunavut, in 1925

Inuit hunter wearing cloth garments, bringing caribou skins back to camp at Koukdjuak, Nunavut, in 1925.jpg.webp) Inuit woman scraping hide, 1946

Inuit woman scraping hide, 1946%252C_Kinngait%252C_Nunavut_(31497043966).jpg.webp) Inuit woman chewing hide to soften it, 1946

Inuit woman chewing hide to soften it, 1946_to_dry%252C_Pangnirtuuq_(Pangnirtung)%252C_Nunavut_(30726111653).jpg.webp) Inuit woman hanging kamiit to dry, 1951

Inuit woman hanging kamiit to dry, 1951.JPG.webp) Alaskan boots, Inupiat, bearded seal, ringed seal, spotted seal, caribou, polar bear, 1989

Alaskan boots, Inupiat, bearded seal, ringed seal, spotted seal, caribou, polar bear, 1989 Two Inuit women wearing modern amautiit (skirted style, akuliq), 1995

Two Inuit women wearing modern amautiit (skirted style, akuliq), 1995

See also

Notes

- Inuktitut syllabics are standardized by the Inuit Cultural Institute to reflect the Romanized spelling of Inuktitut words.[6]

- Kamiit is the Eastern Arctic term for boots, and mukluk is the Western Arctic equivalent. While there are some stylistic differences between them, they are functionally the same. This article refers to all Inuit boots as kamiit for consistency. The singular form of kamiit is kamik.[24]

- Plural form angakkuit[112]

- Plural form sipiniit[119]

- The source uses the Before Present time scale for radiocarbon dating, which considers the present era to begin in 1950.

- Nunavut was not partitioned out from the Northwest Territories until 1999

References

- Osborn, Alan J. (2014). "Eye of the needle: cold stress, clothing, and sewing technology during the Younger Dryas Cold Event in North America". American Antiquity. 79 (1): 48. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 24712726.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 98.

- Hall 2001, p. 117.

- Oakes, Jillian E. (1991). Copper and Caribou Inuit Skin Clothing Production. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press. p. 1. JSTOR j.ctv16nz8.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 43.

- "Writing the Inuit Language". Inuktut Tusaalanga. Pirurvik Centre. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "Through the Lens: Kamiit" (PDF). Inuktitut Magazine. No. 110. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. May 1, 2011. p. 19.

- Kobayashi Issenman, Betty (1985). "Inuit Skin Clothing: Construction and Motifs". Études/Inuit/Studies. 9 (2: Arctic policy): 101–119. JSTOR 42869524.

- "M5837 | Mother's amauti | McCord Museum". collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 104.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 44.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 182.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 43–44.

- "Inuit Clothing and its Construction | Thematic Tours | Musée McCord Museum". collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Ryder, Kassina. "Anatomy of An Amauti". Up Here. Up Here Publishing. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 44–45.

- "The Art and Technique of Inuit Clothing". collections.musee-mccord.qc.ca. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 46.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 46–47.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 50–51.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 50.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 20.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 51.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 50, 54, 60.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 86.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 104.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 85.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 113, 133.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 47.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 47–50.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 54–57.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 215.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 216–217.

- Stenton 1991, p. 4.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 34.

- Oakes, Jill (1991-02-01). "Environmental Factors Influencing Bird-Skin Clothing Production". Arctic and Alpine Research. 23 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1080/00040851.1991.12002822 (inactive 2021-01-14). ISSN 0004-0851.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 32.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 44–47.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 96, 113.

- Hall, Judy (2001). ""Following The Traditions of Our Ancestors": Inuit Clothing Designs". Fascinating challenges: Studying material culture with Dorothy Burnham. University of Ottawa Press. p. 116. JSTOR j.ctv170p6.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 40.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 34.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 44.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 34–36.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 33.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 152.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 36.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 117.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 95.

- Reitan 2006, p. 77–79.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 53.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 60.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 75–76.

- Osborn 2014, p. 49.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 22.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 23.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 64.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 68.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 85.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 29–30.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 71.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 72.

- Renouf, M. A. P.; Bell, T. (2008). "Dorset Palaeoeskimo Skin Processing at Phillip's Garden, Port au Choix, Northwestern Newfoundland". Arctic. 61 (1): 38. ISSN 0004-0843. JSTOR 40513180.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 28.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 78, 82, 84.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 35.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 41.

- Newbery, Nick (2018-12-28). "Traditional Inuit clothing". Above & Beyond. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 42.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 87.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 89.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 52.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 90.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 90–91.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 42.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 180.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 73.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 103–106.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 37.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 103.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 18.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 38.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 104–105.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 40.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 105–106.

- King, J.C.H. (2005). "Introduction". In King, J.C.H. (ed.). Arctic Clothing. McGill-Queen's Press. pp. 15, 20. ISBN 978-0-7735-3008-9.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 112.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 139.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 186.

- Reitan, Janne Beate (2007). Improvisation in Tradition: a Study of Contemporary Vernacular Clothing Design Practiced by Iñupiaq Women of Kaktovik, North Alaska. Oslo: Oslo School of Architecture and Design. pp. 113–114, 120. ISBN 978-82-547-0206-2. OCLC 191444826.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 155.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 187.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 115.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 39.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 46.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 188–191.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 191–193.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 194.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 197–199.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 84.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 182.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 220.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 19.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 180–181.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 181—184.

- Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, p. 37.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 184.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 205.

- Driscoll-Engelstad, Bernadette (2005). "Dance of the Loon: Symbolism and Continuity in Copper Inuit Ceremonial Clothing". Arctic Anthropology. 42 (1): 33–46. doi:10.1353/arc.2011.0010. ISSN 0066-6939. JSTOR 40316636. S2CID 162200500.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 204–205.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 208.

- Walley 2018, p. 279.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 209.

- Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, p. 33.

- Saladin D'Anglure, Bernard (2006). "The Construction of Shamanic Identity among the Inuit of Nunavut and Nunavik". In Christie, Gordon (ed.). Aboriginality and Governance: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Penticton Indian Reserve, British Columbia: Theytus Books. p. 152. ISBN 1894778243.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 210.

- Walley, Meghan (2018). "Exploring Potential Archaeological Expressions of Nonbinary Gender in Pre-Contact Inuit Contexts". Études/Inuit/Studies. 42 (1): 274, 279. doi:10.7202/1064504ar. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 26775769.

- Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, pp. 40–41.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 214.

- Stern, Pamela R. (2010-06-16). Daily Life of the Inuit. ABC-CLIO. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-313-36312-2.

- Smith, Eric Alden; Smith, S. Abigail; et al. (1994). "Inuit Sex-Ratio Variation: Population Control, Ethnographic Error, or Parental Manipulation? [and Comments and Reply]". Current Anthropology. 35 (5): 617. doi:10.1086/204319. ISSN 0011-3204. JSTOR 2744084. S2CID 143679341.

- Stenton, Douglas R. (1991). "The Adaptive Significance of Caribou Winter Clothing for Arctic Hunter-gatherers". Études/Inuit/Studies. 15 (1): 3–4. JSTOR 42869709.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 11.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 13–14.

- Renouf & Bell 2008, p. 36.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 9.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 18.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 234.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1985, p. 102.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 21.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 24.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 172.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 171.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 29.

- Kobayashi Issenman, Betty (1995). "Review of Sanatujut: Pride in Women's Work. Copper and Caribou Inuit Clothing Traditions". Arctic. 48 (3): 302–303. ISSN 0004-0843. JSTOR 40511667.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 174.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 176.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 191.

- Schmidt 2018, p. 124.

- Reitan, Janne B. (2006-06-01). "Inuit vernacular design as a community of practice for learning". CoDesign. 2 (2): 73. doi:10.1080/15710880600645489. ISSN 1571-0882. S2CID 145516337.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 175.

- Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, pp. 41–42.

- "Education". Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada. Retrieved 2020-09-13.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015, pp. 3, 14.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015). Canada's Residential Schools: The Inuit and Northern Experience (PDF). The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Volume 2. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-7735-9829-4. OCLC 933795281.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 179.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 224.

- Herscovici, Alan (1988). "Review of Factors Influencing Kamik Production in Arctic Bay, Northwest Territories". Arctic. 41 (4): 324. doi:10.14430/arctic2003. ISSN 0004-0843. JSTOR 40510755.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 177.

- Driscoll-Engelstad 2005, p. 41.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 242.

- Kobayashi Issenman, Betty (1997). Sinews of Survival: the Living Legacy of Inuit Clothing. Vancouver: UBC Press. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-7748-5641-6. OCLC 923445644.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015, pp. 163, 167.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 226.

- Tulloch, Shelley; Kusugak, Adriana; Uluqsi, Gloria; et al. (December 2013). "Stitching together literacy, culture & well-being: The potential of non-formal learning programs" (PDF). Northern Public Affairs. 2 (2): 28–32.

- Kobayashi Issenman 1997, p. 225.

- Skjerven, Astrid; Reitan, Janne (2017-06-26). Design for a Sustainable Culture: Perspectives, Practices and Education. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-85797-0.

- Reitan 2006, p. 74.

- Oates & Riewe 1995, p. 19, 31.

- Oakes, Jill E.; Riewe, Roderick R. (1995). Our Boots: An Inuit Women's Art. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. p. 17. ISBN 1-55054-195-1. OCLC 34322668.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth (2016). "The SkinBase Project: Providing 3D Virtual Access to Indigenous Skin Clothing Collections from the Circumpolar Area". Études/Inuit/Studies. 40 (2): 193. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 26578202.

- Schmidt 2016, p. 193.

- Schmidt 2016, p. 194.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth (2019). "The SkinBase Project: Providing 3D Virtual Access to Indigenous Skin Clothing Collections from the Circumpolar Area". Études/Inuit/Studies. 40 (2): 191–205. doi:10.7202/1055438ar. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 26578202.

- Schmidt, Anne Lisbeth (2018). "The Holmberg Collection of Skin Clothing from Kodiak Island at the National Museum of Denmark". Études/Inuit/Studies. 42 (1): 117–136. doi:10.7202/1064498ar. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 26775763.

- Schmidt 2016, p. 192.

- MacDonald, John (2014). "Leah Aksaajuq Umik Ivalu Otak (1950-2014)". Études/Inuit/Studies. 38 (1/2): 298. doi:10.7202/1028869ar. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 24368332.

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann (1998). "Yup'ik Elders in Museums: Fieldwork Turned on Its Head". Arctic Anthropology. 35 (2): 56. ISSN 0066-6939. JSTOR 40316487.

- Buijs, Cunera (2018). "Shared Inuit Culture: European Museums and Arctic Communities". Études/Inuit/Studies. 42 (1): 45–46. doi:10.7202/1064495ar. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 26775760.

- Griebeli, Brendan (2016). "Introduction: The Online Future of Inuit Tradition / Introduction: L'avenir numérique de la tradition inuit". Études/Inuit/Studies. 40 (2): 160. ISSN 0701-1008. JSTOR 26578200.

- Oakes, Jill; Wilkins, Heather; Riewe, Rick; Kelker, Doug; Forest, Tom (1995). "Comparison of traditional and manufactured cold weather ensembles". Climate Research. 5 (1): 83–84. doi:10.3354/cr005083. ISSN 0936-577X. JSTOR 24863319.

- Oakes et al. 1995, p. 89.

- Cotel, Aline J.; Golingo, Raymond; Oakes, Jill E.; Riewe, Rick R. (2004). "Effect of ancient Inuit fur parka ruffs on facial heat transfer". Climate Research. 26 (1): 77–84. doi:10.3354/cr026077. ISSN 0936-577X. JSTOR 24868710.

- Dewar, Veronica (2005). "Our Clothing, our Culture, our Identity". In King, J.C.H. (ed.). Arctic Clothing. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7735-3008-9.

- "Inuit 'wear their culture on their sleeve, literally': Inuk designer gears up for Indigenous fashion week | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- "Inappropriation". Up Here Publishing (in Catalan). Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- Bird, Phillip (July 2002). Intellectual Property Rights and the Inuit Amauti: A Case Study (PDF) (Report). Pauktuutit Inuit Women’s Association. p. 3.

- Dewar 2005, p. 25.

- "Nunavut family outraged after fashion label copies sacred Inuit design | CBC Radio". CBC. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- "A brief history of 'the most unique garment known to have been created in the Canadian Arctic' | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- "U.K. fashion house pulls copied Inuit design, here's their apology | CBC Radio". CBC. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- "Canada Goose unveils parkas designed by Inuit designers | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- "Inuit designers launch new line of parkas for Canada Goose | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Inuit clothing. |

- Skin Clothing Online: a database of clothing from Indigenous peoples from the entire circumpolar region