Pangolin

Pangolins, sometimes known as scaly anteaters,[5] are mammals of the order Pholidota (/fɒlɪˈdoʊtə/, from Ancient Greek ϕολιδωτός 'clad in scales').[6] The one extant family, Manidae, has three genera: Manis, Phataginus and Smutsia. Manis comprises the four species found in Asia, while Phataginus and Smutsia include two species each, all found in sub-Saharan Africa.[7] These species range in size from 30 to 100 cm (12 to 39 in). A number of extinct pangolin species are also known.

| Pangolins | |

|---|---|

| |

| Living species of pangolins | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Clade: | Ferae |

| Clade: | Pholidotamorpha |

| Order: | Pholidota Weber, 1904 |

| Subgroups | |

|

| |

| |

| Ranges of living speacies | |

| Synonyms | |

|

list of synonyms:

| |

Pangolins have large, protective keratin scales covering their skin; they are the only known mammals with this feature. They live in hollow trees or burrows, depending on the species. Pangolins are nocturnal, and their diet consists of mainly ants and termites, which they capture using their long tongues. They tend to be solitary animals, meeting only to mate and produce a litter of one to three offspring, which they raise for about two years.

Pangolins are threatened by poaching (for their meat and scales, which are used in Chinese traditional medicine[8]) and heavy deforestation of their natural habitats, and are the most trafficked mammals in the world.[9] As of January 2020, there are eight species of pangolin whose conservation status is listed in the threatened tier. Three (Manis culionensis, M. pentadactyla and M. javanica) are critically endangered, three (Phataginus tricuspis, Manis crassicaudata and Smutsia gigantea) are endangered and two (Phataginus tetradactyla and Smutsia temminckii) are vulnerable on the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature.[10]

Etymology

The name pangolin comes from the Malay word pengguling, meaning "one who rolls up".[11] However, the modern name in Standard Malay is tenggiling; whereas in Indonesian it is trenggiling; and in the Philippine languages it is goling, tanggiling, or balintong (with the same meaning).[12]

Description

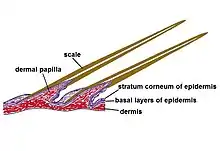

The physical appearance of a pangolin is marked by large hardened overlapping plate-like scales, which are soft on newborn pangolins, but harden as the animal matures.[13] They are made of keratin, the same material from which human fingernails and tetrapod claws are made, and are structurally and compositionally very different from the scales of reptiles.[14] The pangolin's scaled body is comparable in appearance to a pine cone. It can curl up into a ball when threatened, with its overlapping scales acting as armor, while it protects its face by tucking it under its tail. The scales are sharp, providing extra defense from predators.[15]

Pangolins can emit a noxious-smelling chemical from glands near the anus, similar to the spray of a skunk.[16] They have short legs, with sharp claws which they use for burrowing into ant and termite mounds and for climbing.[17]

The tongues of pangolins are extremely long and – like those of the giant anteater and the tube-lipped nectar bat – the root of the tongue is not attached to the hyoid bone, but is in the thorax between the sternum and the trachea.[18] Large pangolins can extend their tongues as much as 40 cm (16 in), with a diameter of only 0.5 cm (1⁄4 in).[19]

Behavior

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Most pangolins are nocturnal animals[20] which use their well-developed sense of smell to find insects. The long-tailed pangolin is also active by day, while other species of pangolins spend most of the daytime sleeping, curled up into a ball ("volvation").[19]

Arboreal pangolins live in hollow trees, whereas the ground-dwelling species dig tunnels to a depth of 3.5 m (11 ft 6 in).[19]

Some pangolins walk with their front claws bent under the foot pad, although they use the entire foot pad on their rear limbs. Furthermore, some exhibit a bipedal stance for some behaviour and may walk a few steps bipedally.[21] Pangolins are also good swimmers.[19]

Diet

Pangolins are insectivorous. Most of their diet consists of various species of ants and termites and may be supplemented by other insects, especially larvae. They are somewhat particular and tend to consume only one or two species of insects, even when many species are available to them. A pangolin can consume 140 to 200 grams (5 to 7 ounces) of insects per day.[22] Pangolins are an important regulator of termite populations in their natural habitats.[23]

Pangolins have very poor vision. They also lack teeth. They rely heavily on smell and hearing, and they have other physical characteristics to help them eat ants and termites. Their skeletal structure is sturdy and they have strong front legs that are useful for tearing into termite mounds.[24] They use their powerful front claws to dig into trees, ground, and vegetation to find prey,[25] then proceed to use their long tongues to probe inside the insect tunnels and to retrieve their prey.

The structure of their tongue and stomach is key to aiding pangolins in obtaining and digesting insects. Their saliva is sticky,[24] causing ants and termites to stick to their long tongues when they are hunting through insect tunnels. Without teeth, pangolins also lack the ability to chew;[26] however, while foraging, they ingest small stones (gastroliths) which accumulate in their stomachs to help to grind up ants.[27] This part of their stomach is called the gizzard, and it is also covered in keratinous spines.[28] These spines further aid in the grinding up and digestion of the pangolin's prey.

Some species, such as the tree pangolin, use their strong, prehensile tails to hang from tree branches and strip away bark from the trunk, exposing insect nests inside.[29]

Reproduction

Pangolins are solitary and meet only to mate. Males are larger than females, weighing up to 40% more. While the mating season is not defined, they typically mate once each year, usually during the summer or autumn. Rather than the males seeking out the females, males mark their location with urine or feces and the females will find them. If there is competition over a female, the males will use their tails as clubs to fight for the opportunity to mate with her.[31]

Gestation periods differ by species, ranging from roughly 70 to 140 days.[32] African pangolin females usually give birth to a single offspring at a time, but the Asiatic species may give birth to from one to three.[19] Weight at birth is 80 to 450 g (2 3⁄4 to 15 3⁄4 oz) and the average length is 150 mm (6 in). At the time of birth, the scales are soft and white. After several days, they harden and darken to resemble those of an adult pangolin. During the vulnerable stage, the mother stays with her offspring in the burrow, nursing it, and wraps her body around it if she senses danger. The young cling to the mother's tail as she moves about, although in burrowing species, they remain in the burrow for the first two to four weeks of life. At one month, they first leave the burrow riding on the mother's back. Weaning takes place around three months of age, at which stage the young begin to eat insects in addition to nursing. At two years of age, the offspring are sexually mature and are abandoned by the mother.[33]

Classification and phylogeny

Taxonomy

- Order: Pholidota (Weber, 1904) (pangolins)

- Genus: †Euromanis (Gaudin, Emry & Wible, 2009)

- †Euromanis krebsi (Storch & Martin, 1994)

- Family: †Eurotamanduidae (Szalay & Schrenk, 1994)

- Genus: †Eurotamandua (Storch, 1981)

- †Eurotamandua joresi (Storch, 1981)

- Genus: †Eurotamandua (Storch, 1981)

- Suborder: Eupholidota (Gaudin, Emry & Wible, 2009) (true pangolins)

- Superfamily: †Eomanoidea (Gaudin, Emry & Wible, 2009)

- Superfamily: Manoidea (Gaudin, Emry & Wible, 2009)

- Family: Manidae (Gray, 1821) (pangolins)

- Subfamily: Maninae (Gray, 1821)

- Genus: Manis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Asiatic pangolins)

- Manis crassicaudata (Gray, 1827) (Indian pangolin)

- Manis pentadactyla (Linnaeus, 1758) (Chinese pangolin)

- †Manis hungarica (Kormos, 1934)

- †Manis lydekkeri (Dubois, 1908)

- Subgenus: Paramanis (Pocock, 1924)

- Manis javanica (Desmarest, 1822) (Sunda pangolin)

- Manis culionensis (de Elera, 1895) (Philippine pangolin)

- †Manis paleojavanica (Dubois, 1907)

- Genus: Manis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Asiatic pangolins)

- Subfamily: Phatagininae (Gaubert, 2017) (small African pangolins)

- Genus: Phataginus (Rafinesque, 1821) (African tree pangolins)

- Phataginus tetradactyla (Linnaeus, 1766) (Long-tailed pangolin)

- Phataginus tricuspis (Rafinesque, 1821) (Tree pangolin)

- Genus: Phataginus (Rafinesque, 1821) (African tree pangolins)

- Subfamily: Smutsiinae (Gray, 1873) (large African pangolins)

- Genus: Smutsia (Gray, 1865) (African ground pangolins)

- Smutsia gigantea (Illiger, 1815) (Giant pangolin)

- Smutsia temmincki (Smuts, 1832) (Ground pangolin)

- Genus: Smutsia (Gray, 1865) (African ground pangolins)

- Incertae sedis

- †Fayum pangolin (manidae sp. [DPC 3972 & DPC 4364] (Gebo & Rasmussen, 1985))[34]

- Subfamily: Maninae (Gray, 1821)

- Family: †Patriomanidae (Szalay & Schrenk 1998) [sensu Gaudin, Emry & Pogue, 2006]

- Genus: †Cryptomanis (Gaudin, Emry & Pogue, 2006)

- †Cryptomanis gobiensis (Gaudin, Emry & Pogue, 2006)

- Genus: †Patriomanis (Emry, 1970)

- †Patriomanis americana (Emry, 1970)

- Genus: †Cryptomanis (Gaudin, Emry & Pogue, 2006)

- Incertae sedis

- Genus: †Necromanis (Filhol, 1893)

- †Necromanis franconica (Quenstedt, 1886)

- †Necromanis parva (Koenigswald, 1969)

- †Necromanis quercyi (Filhol, 1893)

- Genus: †Necromanis (Filhol, 1893)

- Family: Manidae (Gray, 1821) (pangolins)

- Genus: †Euromanis (Gaudin, Emry & Wible, 2009)

Among placentals

The order Pholidota was considered to be the sister taxon to Xenarthra (neotropical anteaters, sloths, and armadillos), but recent genetic evidence indicates their closest living relatives are the carnivorans, with which they form a clade termed either Ferae or Ostentoria.[35][36][37][38] Fossil groups like the creodonts[39] and palaeanodonts are even closer relatives to pangolins (the latter group being classified with pangolins in the clade Pholidotamorpha[40]). The split between carnivorans and pangolins is estimated to have occurred 79-87 Ma (million years) ago.[38][41]

| Phylogenetic position of the order Pholidota in the order-level cladogram of Boreoeutheria (only living groups) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The cladogram has been reconstructed from mitochondrial and nuclear DNA and protein characters. |

| Phylogenetic position of order Pholidota within clade Ferae.[42][43] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| Phylogenetic position of pangolins within order Pholidota.[7][40] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Among Manidae

The first dichotomy in the phylogeny of extant Manidae separates Asian pangolins (Manis) from African pangolins (Smutsia and Phataginus). Within the former, Manis pentadactyla is the sister group to a clade comprising M. crassicaudata and M. javanica. Within the latter, a split separates the large terrestrial African pangolins of genus Smutsia from the small arboreal African pangolins of genus Phataginus.[41]

| Phylogenetic relationships of genera and species of Manidae | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The cladogram has been reconstructed from mitochondrial genomes and a handful of nuclear DNA sequences, and fossil record.[7][40][44][41] |

Asian and African pangolins are thought to have diverged about 38-47 Ma ago.[38][41] Moreover, the basal position of Manis within Pholidota[38][44] suggests the group originated in Eurasia, consistent with their laurasiatherian phylogeny.[38]

Threats

_(32575640450).jpg.webp)

Pangolins are in high demand for Chinese traditional medicine in southern China and Vietnam because their scales are believed to have medicinal properties. Their meat is also considered a delicacy.[46][47][48][49][50] 100,000 are estimated to be trafficked a year to China and Vietnam,[51] amounting to over one million over the past decade.[52][53] This makes it the most trafficked animal in the world.[52][54] This, coupled with deforestation, has led to a large decrease in the numbers of pangolins. Some species, such as Manis pentadactyla have become commercially extinct in certain ranges as a result of overhunting.[55] In November 2010, pangolins were added to the Zoological Society of London's list of evolutionarily distinct and endangered mammals.[56] All eight species of pangolin are assessed as threatened by the IUCN, while three are classified as critically endangered.[10] All pangolin species are currently listed under Appendix I of CITES which prohibits international trade, except when the product is intended for non-commercial purposes and a permit has been granted.[57]

Pangolins are also hunted and eaten in Ghana and are one of the more popular types of bushmeat, while local healers use the pangolin as a source of traditional medicine.[58]

Though pangolins are protected by an international ban on their trade, populations have suffered from illegal trafficking due to beliefs in East Asia that their ground-up scales can stimulate lactation or cure cancer or asthma.[59] In the past decade, numerous seizures of illegally trafficked pangolin and pangolin meat have taken place in Asia.[60][61][62][63] In one such incident in April 2013, 10,000 kilograms (22,000 pounds) of pangolin meat were seized from a Chinese vessel that ran aground in the Philippines.[64][65] In another case in August 2016, an Indonesian man was arrested after police raided his home and found over 650 pangolins in freezers on his property.[66] The same threat is reported in Nigeria, where the animal is on the verge of extinction due to overexploitation.[67] The overexploitation comes from hunting pangolins for game meat and the reduction of their forest habitats due to deforestation caused by timber harvesting.[68] The pangolin are hunted as game meat for both medicinal purposes and food consumption.[68]

Virology

COVID-19 infection

The nucleic acid sequence of a specific receptor-binding domain of the spike protein belonging to coronaviruses taken from pangolins was found to be a 99% match with SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus which causes COVID-19 and is responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic.[69][70] Researchers in Guangzhou, China, hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 had originated in bats, and prior to infecting humans, was circulating among pangolins. The illicit Chinese trade of pangolins for use in traditional Chinese medicine was suggested as a vector for human transmission.[69][71] The discovery of multiple lineages of pangolin coronavirus and their similarity to SARS-CoV-2 indicate that pangolins are hosts for SARS-CoV-2-like coronaviruses.[72] However, whole-genome comparison found that the pangolin and human coronaviruses share only up to 92% of their RNA.[74] Ecologists worried that the early speculation about pangolins being the source may have led to mass slaughters, endangering the animals further, which was similar to what happened to Asian palm civets during the SARS outbreak.[75]

Pestivirus and Coltivirus

In 2020, two novel RNA viruses distantly related to pestiviruses and coltiviruses have been detected in the genomes of dead Manis javanica and Manis pentadactyla.[76] To refer to both sampling site and hosts, they were named Dongyang pangolin virus (DYPV) and Lishui pangolin virus (LSPV). The DYPV pestivirus was also identified in Amblyomma javanense nymph ticks from a diseased pangolin.[76]

Folk medicine

Pangolin scales and flesh are used as ingredients for various traditional Chinese medicine preparations.[77] While no scientific evidence exists for the efficacy of those practices, and they have no logical mechanism of action,[77][78][79][80][81] their popularity still drives the black market for animal body parts, despite concerns about toxicity, transmission of diseases from animals to humans, and species extermination.[77][82] The ongoing demand for parts as ingredients continues to fuel pangolin poaching, hunting and trading.[83]

In the 21st century, the main uses of pangolin scales are quackery practices based on unproven claims the scales dissove blood clots, promote blood circulation, or help lactating women secrete milk.[77][84] The supposed health effects of pangolin meat and scales claimed by folk medicine practitioners and quacks are based on their consumption of ants, long tongues, and protective scales.[77] The Chinese name chuan shan jia (穿山甲) "penetrating-the-mountain scales") emphasizes the idea of penetration or passing through even massive obstructions such as mountains, plus the distinctive scales which embody penetration and protection.

The official pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China included Chinese pangolin scales as an ingredient in TCM formulations.[84] Pangolins were removed from the pharmacopoeia starting from the first half of 2020.[85] Although pangolin scales have been removed from the list of raw ingredients, the scales are still listed as a key ingredient in various medicines.[86]

The first record of pangolin scales occurs in Ben Cao Jinji Zhu ("Variorum of Shennong's Classic of Materia Medica", 500 CE), which recommends pangolin scales for protection against ant bites; burning the scales as a cure for people crying hysterically during the night.[84] During the Tang dynasty, a recipe for expelling evil spirits with a formulation of scales, herbs, and minerals appeared in 682, and in 752 CE the idea that pangolin scales could also stimulate milk secretion in lactating women, one of the main uses today, was recommended in the Wai Tai Mi Yao ("Arcane Essentials from the Imperial Library").[84] In the Song dynasty, the notion of penetrating and clearing blockages was emphasized in the Taiping sheng hui fan ("Formulas from Benevolent Sages Compiled During the Era of Peace and Tranquility"), compiled by Wang Huaiyin in 992.[84]

Conservation

As a result of increasing threats to pangolins, mainly in the form of illegal, international trade in pangolin skin, scales, and meat, these species have received increasing conservation attention in recent years. As of January 2020, the IUCN considered all eight species of pangolin on its Red List of Threatened Species as threatened.[10] The IUCN SSC Pangolin Specialist Group launched a global action plan to conserve pangolins, dubbed "Scaling up Pangolin Conservation", in July 2014. This action plan aims to improve all aspects of pangolin conservation with an added emphasis on combating poaching and trafficking of the animal, while educating communities in its importance.[52] Another suggested approach to fighting pangolin (and general wildlife) trafficking consists in "following the money" rather than "the animal", which aims to disrupt smugglers' profits by interrupting money flows. Financial intelligence gathering could thus become a key tool in protecting these animals, although this opportunity is often overlooked.[51] In 2018, a Chinese NGO launched the Counting Pangolins movement, calling for joint efforts to save the mammals from trafficking.[87][88][89] Wildlife conservation group TRAFFIC has identified 159 smuggling routes used by pangolin traffickers and aims to shut these down.[90]

.jpg.webp)

Many attempts have been made to breed pangolins in captivity, but due to their reliance on wide-ranging habitats and very particular diets, these attempts are often unsuccessful.[32][91] Pangolins have significantly decreased immune responses due to a genetic dysfunction, making them extremely fragile.[92] They are susceptible to diseases such as pneumonia and the development of ulcers in captivity, complications that can lead to an early death.[32] In addition, pangolins rescued from illegal trade often have a higher chance of being infected with parasites such as intestinal worms, further lessening their chance for rehabilitation and reintroduction to the wild.[32] Recently, researchers have been able to improve artificial pangolin habitats to allow for breeding of pangolins, providing some hope for future reintroduction of these species into their natural habitats.[13]

The idea of farming pangolins to reduce the number being illegally trafficked is being explored with little success.[93] The third Saturday in February is promoted as World Pangolin Day by the conservation NPO Annamiticus.[94]

In 2017, Jackie Chan made a public service announcement called WildAid: Jackie Chan & Pangolins (Kung Fu Pangolin).[95]

In December 2020, a study found that it is "not too late" to establish conservation efforts for Philippine pangolins (Manis culionensis), a species that is only found on the island province of Palawan.[96][97]

Taiwan

Taiwan is one of the few conservation grounds for pangolins in the world after the country enacted the 1989 Wildlife Conservation Act.[98] The introduction of Wildlife Rehabilitation Centers in places like Luanshan (Yanping Township) in Taitung and Xiulin townships in Hualien became important communities for protecting pangolins and their habitats and has greatly improved the survival of pangolins. These centers work with local aboriginal tribes and forest police in the National Police Agency to prevent poaching, trafficking, and smuggling of pangolins, especially to black markets in China. These centers have also helped to reveal the causes of death and injury among Taiwan's pangolin population.[99] Today, Taiwan has the highest population density of pangolins in the world.[100]

References

- Mark S Springer, Christopher A Emerling, John Gatesy, Jason Randall, Matthew A. Collin, Nikolai Hecker, Michael Hiller, Frédéric Delsuc (2019) "Odontogenic ameloblast-associated (ODAM) is inactivated in toothless/enamelless placental mammals and toothed whales". BMC Evolutionary Biology

- Zagorodniuk, I. (2008.) "Scientific names of mammal orders: from descriptive to uniform" Visnyk of Lviv University, Biology series, Is. 48. P. 33-43

- E. D. Cope. (1889.) "The Edentata of North America." American Naturalist 23(272):657-664

- Arthur Sperry Pearse, (1936.) "Zoological names. A list of phyla, classes, and orders, prepared for section F, American Association for the Advancement of Science" American Association for the Advancement of Science

- Thomas, Oldfield; Lydekker, Richard (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- Brown, Roland Wilbur (1956). The Composition of Scientific Words. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 604.

- Gaudin, Timothy (28 August 2009). "The Phylogeny of Living and Extinct Pangolins (Mammalia, Pholidota) and Associated Taxa: A Morphology Based Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Mammalian Evolution. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media. 16 (4): 235–305. doi:10.1007/s10914-009-9119-9. S2CID 1773698. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "Chinese Medicine and the Pangolin". Nature. 141 (3558): 72. 1 January 1938. Bibcode:1938Natur.141R..72.. doi:10.1038/141072b0.

- Goode, Emilia (March 31, 2015). "A Struggle to Save the Scaly Pangolin". The New York Times. New York City: New York Times Company. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- "Manidae Family search". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Pearsall, Judy, ed. (2002). Concise Oxford English Dictionary (10th ed.). Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. p. 1030. ISBN 978-0-19-860572-0.

- Vergara, Benito S.; Idowu, Panna Melizah H.; Sumangil, Julia H.; Gonzales, Juan Carlos; Dans, Andres. Interesting Philippine Animals. Washington, D.C.: Island Publishing House, Inc. ISBN 9718538550.

- Yu, Jingyu; Jiang, Fulin; Peng, Jianjun; Yin, Xilin; Ma, Xiaohua (October 2015). "The First Birth and Survival of Cub in Captivity of Critically Endangered Malayan Pangolin (Manis javanica)". Agricultural Science & Technology. Irvine, California: Juniper Publishers. 16 (10). ISSN 2471-6774.

- Spearman, R.I.C. (2008). "On the nature of the horny scales of the pangolin". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. 46 (310): 267–273. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1967.tb00508.x.

- Wang, Bin (2016). "Pangolin armor: Overlapping, structure, and mechanical properties of the keratinous scales". Acta Biomaterialia. Oxfordshire, England: Elsevier. 41: 60–74. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2016.05.028. PMID 27221793.

- "Meet the Pangolin!". Pangolins.org. 2015. Archived from the original on 2015-02-22.

- "Manis tricuspis tree pangolin". Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan. 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-12-21.

- Chan, Lap-Ki (1995). "Extrinsic Lingual Musculature of Two Pangolins (Pholidota: Manidae)". Journal of Mammalogy. Oxfordshire, England: Oxford University Press. 76 (2): 472–480. doi:10.2307/1382356. JSTOR 1382356.

- Mondadori, Arnoldo, ed. (1988). Great Book of the Animal Kingdom. New York City: Arch Cape Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0517667910.

- Wilson, Amelia E. (January 1994). "Husbandry of pangolins Manis spp". International Zoo Yearbook. 33 (1): 248–251. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1090.1994.tb03578.x.

- Mohapatra, Rajesh K.; Panda, Sudarsen (2014). "Behavioural descriptions of Indian pangolins (Manis crassicaudata) in captivity". Journal of Zoology. London, England: Wiley-Blackwell. 2014: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2014/795062.

- Grosshuesch, Craig (2012). "Rollin' With the Pangolin – Diet". La Crosse, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014.

- Ma, Jing-E; Li, Lin-Miao; Jiang, Hai-Ying; Zhang, Xiu-Juan; Li, Juan; Li, Guan-Yu; Yuan, Li-Hong; Wu, Jun; Chen, Jin-Ping (2017). "Transcriptomic analysis identifies genes and pathways related to myrmecophagy in the Malayan pangolin (Manis javanica)". PeerJ. Corte Madera, California: O'Reilly Media. 5: e4140. doi:10.7717/peerj.4140. PMC 5742527. PMID 29302388.

- Rose, Kd; Gaudin, Tj (2010). Xenarthra and Pholidota (Armadillos, Anteaters, Sloths and Pangolins). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0001556.pub2. ISBN 978-0470015902.

- Coulson, Ian M; Heath, Martha E (Dec 1997). "Foraging behaviour and ecology of the Cape pangolin (Manis temminckii) in north-western Zimbabwe". African Journal of Ecology. 35 (4): 361–369. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1997.101-89101.x – via EBSCO.

- Gutteridge, Lee (2008). The South African Bushveld: A Field Guide from the Waterberg. Pinetown, South Africa: 30° South Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-920143-13-8.

- Wildlife of the World. London, England: Dorling Kindersley. 2015. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-4654-4959-7.

- Davit-Béal, Tiphaine; Tucker, Abigail S.; Sire, Jean-Yves (April 1, 2009). "Loss of teeth and enamel in tetrapods: fossil record, genetic data and morphological adaptations". Journal of Anatomy. New York City: John Wiley & Sons. 214 (4): 477–501. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2009.01060.x. PMC 2736120. PMID 19422426.

- Prothero, Donald R. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Prehistoric Mammals. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-4008-8445-2.

- Fabro, Keith Anthony S. (10 June 2019). "All hope is not lost for vanishing Palawan pangolin". Rappler. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- Grosshuesch, Craig (2012). "Rollin' With the Pangolin - Reproduction". University of Wisconsin–La Crosse. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014.

- Hua, Liushuai; Gong, Shiping; Wang, Fumin; Li, Weiye; Ge, Yan; Li, Xiaonan; Hou, Fanghui (8 June 2015). "Captive breeding of pangolins: current status, problems and future prospects". ZooKeys (507): 99–114. doi:10.3897/zookeys.507.6970. PMC 4490220. PMID 26155072.

- Dickman, Christopher R. (1984). MacDonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 780–781. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- Daniel Gebo, D. Tab Rasmussen (1985.) "The Earliest Fossil Pangolin (Pholidota: Manidae) from Africa" Journal of Mammalogy 66(3):538

- Murphy WJ, Eizirik E, et al. (December 14, 2001). "Resolution of the Early Placental Mammal Radiation Using Bayesian Phylogenetics". Science. 294 (5550): 2348–2351. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2348M. doi:10.1126/science.1067179. PMID 11743200. S2CID 34367609.

- Amrine-Madsen, H.; Koepfli, K.P.; Wayne, R.K.; Springer, M.S. (2003). "A new phylogenetic marker, apolipoprotein B, provides compelling evidence for eutherian relationships". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 28 (2): 225–240. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00118-0. PMID 12878460.

- Beck, Robin; Bininda-Emonds, Olaf; Cardillo, Marcel; Liu, Fu-Guo; Purvis, Andy (2006). "A higher-level MRP supertree of placental mammals". BMC Evolutionary Biology. London, England: BioMed Central. 6 (1): 93. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-93. PMC 1654192. PMID 17101039.

- Du Toit, Z.; Grobler, J. P.; Kotzé, A.; Jansen, R.; Brettschneider, H.; Dalton, D. L. (2014). "The complete mitochondrial genome of Temminck's ground pangolin (Smutsia temminckii; Smuts, 1832) and phylogenetic position of the Pholidota (Weber, 1904)". Gene. 551 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2014.08.040. PMID 25158133.

- Halliday, Thomas J. D.; Upchurch, Paul; Goswami, Anjali (December 21, 2015). "Resolving the relationships of Paleocene placental mammals". Biological Reviews. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Philosophical Society. 92 (1): 521–550. doi:10.1111/brv.12242. PMC 6849585. PMID 28075073.

- Kondrashov, Peter; Agadjanian, Alexandre K. (2012). "A nearly complete skeleton of Ernanodon (Mammalia, Palaeanodonta) from Mongolia: morphofunctional analysis". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. Bethesda Maryland: Taylor & Francis. 32 (5): 983–1001. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.694319. S2CID 86059673.

- Gaubert, Philippe; Antunes, Agostinho; Meng, Hao; Miao, Lin; Peigné, Stéphane; Justy, Fabienne; Njiokou, Flobert; Dufour, Sylvain; Danquah, Emmanuel; Alahakoon, Jayanthi; Verheyen, Erik (2018-05-11). "The Complete Phylogeny of Pangolins: Scaling Up Resources for the Molecular Tracing of the Most Trafficked Mammals on Earth". Journal of Heredity. 109 (4): 347–359. doi:10.1093/jhered/esx097. PMID 29140441.

- Solé, Floréal; Ladevèze, Sandrine (2017). "Evolution of the hypercarnivorous dentition in mammals (Metatheria, Eutheria) and its bearing on the development of tribosphenic molars". Evolution & Development. 19 (2): 56–68. doi:10.1111/ede.12219. PMID 28181377. S2CID 46774007.

- Prevosti, F. J., & Forasiepi, A. M. (2018). "Introduction. Evolution of South American Mammalian Predators During the Cenozoic: Paleobiogeographic and Paleoenvironmental Contingencies"

- du Toit, Z.; du Plessis, M.; Dalton, D. L.; Jansen, R.; Paul Grobler, J.; Kotzé, A. (2017). "Mitochondrial genomes of African pangolins and insights into evolutionary patterns and phylogeny of the family Manidae". BMC Genomics. 18 (1): 746. doi:10.1186/s12864-017-4140-5. PMC 5609056. PMID 28934931.

- Sutter, John D. (April 2014). "Change the List: The Most Trafficked Mammal You've Never Heard Of". CNN.

- van Uhm, D.P. (2016). The Illegal Wildlife Trade: Inside the World of Poachers, Smugglers and Traders (Studies of Organized Crime). New York: Springer.

- Hance, Jeremy (29 July 2014). "Over a million pangolins slaughtered in the last decade". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Challender, D.; Willcox, D.H.A.; Panjang, E.; Lim, N.; Nash, H.; Heinrich, S. & Chong, J. (2019). "Manis javanica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T12763A123584856. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Actman, Jani (20 December 2015). "Crime Blotter: Pangolin Scales, Tiger Skins, and More". National Geographic. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Cruise, Adam (18 April 2015). "Tiger Eyes, Crocodile Penis: It's What's For Dinner in Malaysia". National Geographic. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Haenlein, Alexandria Reid, Cathy; Keatinge, Tom (2018-10-10). "What's the secret to saving this rare creature?". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- "Action Plan". www.pangolinsg.org. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- Ingram, Daniel J.; Coad, Lauren; Abernethy, Katharine A.; Maisels, Fiona; Stokes, Emma J.; Bobo, Kadiri S.; Breuer, Thomas; Gandiwa, Edson; Ghiurghi, Andrea; Greengrass, Elizabeth; Holmern, Tomas (March 2018). "Assessing Africa-Wide Pangolin Exploitation by Scaling Local Data: Assessing African pangolin exploitation". Conservation Letters. 11 (2): e12389. doi:10.1111/conl.12389.

- Fletcher, Martin (2015-02-05). "The world's most-trafficked mammal – and the scaliest". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-10-10.

- Challender, D.; Wu, S.; Kaspal, P.; Khatiwada, A.; Ghose, A.; Ching-Min Su, N.; Suwal, Laxmi (2019). "Manis pentadactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T12764A123585318. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Agence France-Presse (November 19, 2010). "'Asian unicorn' and scaly anteater make endangered list". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- "The CITES Appendices". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. CITES. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Boakye, Maxwell Kwame; Pietersen, Darren William; Kotzé, Antoinette; Dalton, Desiré-Lee; Jansen, Raymond (2015-01-20). "Knowledge and uses of African pangolins as a source of traditional medicine in Ghana". PLOS ONE. 10 (1): e0117199. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1017199B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117199. PMC 4300090. PMID 25602281.

- Wassener, Bettina (12 March 2013). "No Species Is Safe From Burgeoning Wildlife Trade". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

- Sutter, John D. (3 April 2014). "The Most Trafficked Mammal You've Never Heard Of". CNN. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015.

- "23 tonnes of pangolins seized in a week". Traffic.org. 17 March 2008. Archived from the original on 26 November 2014.

- Watts, Jonathan (25 May 2007). "'Noah's Ark' of 5,000 rare animals found floating off the coast of China". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014.

- "Asia in Pictures". The Wall Street Journal. 27 May 2012. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

- Carrington, Damian (15 April 2013). "Chinese vessel on Philippine coral reef caught with illegal pangolin meat". Associated Press. London. Archived from the original on 2013-04-16. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- Molland, Judy (16 April 2013). "Boat Filled With 22,000 Pounds Of Pangolin Hits Endangered Coral Reef". London: Care2. Archived from the original on 2013-04-18. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- "Indonesian man arrested as 650 pangolins found dead in freezers". BBC News. 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

- The Daily Trust (Nigeria), Saturday 18 February 2017

- Sodeinde, Olufemi A.; Adedipe, Segun R. (24 April 2009). "Pangolins in south-west Nigeria – current status and prognosis". Oryx. 28 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1017/S0030605300028283.

- Cyranoski, David (2020-02-07). "Did pangolins spread the China coronavirus to people?". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-00364-2. S2CID 212825975.

- Liu, P.; Chen, W.; Chen, J.-P. (2019). "Viral Metagenomics Revealed Sendai Virus and Coronavirus Infection of Malayan Pangolins (Manis javanica)". Viruses. 11 (11): 979. doi:10.3390/v11110979. PMC 6893680. PMID 31652964.

- Bryner, Jeanna (March 15, 2020). "1st known case of coronavirus traced back to November in China". LiveScience. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- Lam, Tommy Tsan-Yuk; Shum, Marcus Ho-Hin; Zhu, Hua-Chen; Tong, Yi-Gang; Ni, Xue-Bing; Liao, Yun-Shi; Wei, Wei; Cheung, William Yiu-Man; Li, Wen-Juan; Li, Lian-Feng; Leung, Gabriel M.; Holmes, Edward C.; Hu, Yan-Ling; Guan, Yi (26 March 2020). "Identifying SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins". Nature. 583 (7815): 282–285. Bibcode:2020Natur.583..282L. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. PMID 32218527.

- Zhang, Tao; Wu, Qunfu; Zhang, Zhigang (19 March 2020). "Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak". Current Biology. 30 (7): 1346–1351.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.022. PMC 7156161. PMID 32197085.

- "Civet Cat Slaughter To Fight SARS". CBSNews. 11 January 2004. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Gao, Wen-Hua; Lin, Xian-Dan; Chen, Yan-Mei; Xie, Chun-Gang; Tan, Zhi-Zhou; Zhou, Jia-Jun; Chen, Shuai; Holmes, Edward C; Zhang, Yong-Zhen (2020-01-01). "Newly identified viral genomes in pangolins with fatal disease". Virus Evolution. 6 (1): veaa020. doi:10.1093/ve/veaa020. PMC 7151644. PMID 32296543.

- Mariëtte Le Roux (25 March 2018). "Quackery and superstition: species pay the cost". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- Liu, Quan; Cao, Lili; Zhu, Xing-Quan (2014-08-01). "Major emerging and re-emerging zoonoses in China: a matter of global health and socioeconomic development for 1.3 billion". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 25: 65–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.04.003. ISSN 1201-9712. PMC 7110807. PMID 24858904.

- "Chinese Medicine and the Pangolin". Nature. 141 (3558): 72. 1938-01-01. Bibcode:1938Natur.141R..72.. doi:10.1038/141072b0. ISSN 1476-4687.

- Steven Novella (25 January 2012). "What Is Traditional Chinese Medicine?". Science-based Medicine. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- Zhouying Jin (2005). Global Technological Change: From Hard Technology to Soft Technology. Intellect Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-84150-124-6. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

The vacuum created by China's failure to adequately support a disciplined scientific approach to traditional Chinese medicine has been filled by pseudoscience

- Zhang, Fang; Kong, Lin-lin; Zhang, Yi-ye; Li, Shu-Chuen (2012). "Evaluation of Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life and Cost Effectiveness of Traditional Chinese Medicine: A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials". The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 18 (12): 1108–20. doi:10.1089/acm.2011.0315. ISSN 1075-5535. PMID 22924383.

- Boyle, Louise (30 June 2020). "'If we don't buy, they don't die': Tackling the global demand that's driving the illegal wildlife trade". The Independent. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Xing, S.; Bonebrake, T. C.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, M.; Ades, G.; Shaw, D.; Zhou, Y. (2019). "Meat and medicine: historic and contemporary use in Asia". In Challender, D.; Nash, H.; Waterman, C. (eds.). Pangolins: Science, Society and Conservation (First ed.). Academic Press. p. 233. ISBN 9780128155073. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Maron, Dina Fine (9 June 2020). "Pangolins receive surprising lifeline with new protections in China". National Geographic. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- "Did China really ban the pangolin trade? Not quite, investigators say". Mongabay Environmental News. 2020. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- Xinhua News (2018-11-21) Spotlight: Pangolin conservationists call for ban on illegal trade of mammal products

- China Plus (2017-02-18) World Pangolin Day: Conservationists demand greater protection to stop extinction

- Xinhua News (2018-06-08) How China is combating wildlife trafficking in Africa

- "Pangolins – Species we work with at TRAFFIC". www.traffic.org. Retrieved 2019-01-10.

- Aitken-Palmer, Copper; deMaar, Thomas W.; Johnson, James G.; Langan, Jennifer; Bergmann, Jonathan; Chinnadurai, Sathya; Guerra, Hector; Carboni, Deborah A.; Adkesson, Michael J. (September 2019). "Complications Associated with Pregnancy and Parturition in African White-bellied Pangolins (Phataginus Tricuspis)". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 50 (3): 678–687. doi:10.1638/2019-0019. S2CID 202727948.

- Choo, S. W.; et al. (2016). "Pangolin genomes and the evolution of mammalian scales and immunity". Genome Research. 26 (10): 1312–1322. doi:10.1101/gr.203521.115. PMC 5052048. PMID 27510566.

- Challender, Daniel W. S.; Sas-Rolfes, Michael't; Ades, Gary W. J.; Chin, Jason S. C.; Ching-Min Sun, Nick; Chong, Ju lian; Connelly, Ellen; Hywood, Lisa; Luz, Sonja; Mohapatra, Rajesh K.; de Ornellas, Paul (2019-10-01). "Evaluating the feasibility of pangolin farming and its potential conservation impact". Global Ecology and Conservation. 20: e00714. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00714.

- "World Pangolin Day – About". Pangolins.org/Annamiticus. 2011-10-26.

- "Jackie Chan fights for pangolins". China Daily. 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2019-03-17.

- "It's not too late – yet – to save the Philippine pangolin, study finds". Mongabay Environmental News. 2021-01-27. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- "Scaling up local ecological knowledge to prioritise areas for protection: Determining Philippine pangolin distribution, status and threats". Global Ecology and Conservation. 24: e01395. 2020-12-01. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01395. ISSN 2351-9894.

- "Taiwan's Path to Pangolin Conservation : How a Mega Pangolin Leather Exporter Transformed into a Conservation Specialist". The Reporter (Taiwan). 2019-06-23. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- Pei, Curtis Jai-Chyi; Chen, Chen-Chih; Chi, Meng-Jou; Lin, Wen-Chi; Lin, Jing-Shiun; Arora, Bharti; Sun, Nick Ching-Min (2019-02-06). "Mortality and morbidity in wild Taiwanese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla pentadactyla)". PLOS ONE. 14 (2): e0198230. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1498230S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198230. PMC 6364958. PMID 30726204.

- "Taiwanese Researchers Collaborate With Locals In Pangolin Conservation". The News Lens. 2019-09-25. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pholidota. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Pholidota. |

| Look up pangolin in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- ZSL Pangolin Conservation

- Pangolin: Wildlife summary from the African Wildlife Foundation

- Tree of Life of Pholidota

- National Geographic video of a pangolin

- Proceedings of the Workshop on Trade and Conservation of Pangolins Native to South and Southeast Asia (PDF)

- The Phylogeny of Living and Extinct Pangolins (Mammalia, Pholidota) and Associated Taxa: A Morphology Based Analysis (PDF)

- Bromley, Victoria (Director/Producer), Young, Nora (Narrator/Host), Diekmann, Maria (2018). Nature: The World's Most Wanted Animal. United States: PBS.

- Coronavirus: Revenge of the Pangolins? The New York Times, March 6, 2020.