People's Action Party

The People's Action Party (abbreviation: PAP) is a major conservative centre-right[8] political party in Singapore and is one of the three contemporary political parties represented in Parliament.[9][10]

People's Action Party | |

|---|---|

| |

| Malay name | Parti Tindakan Rakyat |

| Chinese name | 人民行动党 Rénmín Xíngdòngdǎng |

| Tamil name | மக்கள் செயல் கட்சி Makkaḷ Ceyal Kaṭci |

| Abbreviation | PAP |

| Leader | Lee Hsien Loong |

| Chairman | Gan Kim Yong |

| Secretary-General | Lee Hsien Loong |

| Vice Chairman | Masagos Zulkifli |

| Assistant Secretaries-General | |

| Founders | |

| Founded | 21 November 1954 |

| Preceded by | Malayan Forum |

| Headquarters | PCF Building 57B New Upper Changi Road #01-1402 Singapore 463057 |

| Youth wing | Young PAP |

| Ideology | Conservatism[1] Social conservatism[2] National conservatism[3] Economic liberalism[4] Civic nationalism[5][6] Multiracialism Secularism[7] |

| Political position | Centre-right[8] |

| Colours | White Red Blue |

| Slogan | "Our lives, our jobs, our future" |

| Parliament | 83 / 104 |

| Website | |

| pap | |

The ruling party since 1959, it was founded in 1954 as a pro-independence political party descended from an earlier student organization, and it has gone on to dominate the political system of the nation. The PAP has dominated Singapore's politics and has been credited as being central to the city-state's rapid political, social and economic development.[11]

Positioned on the centre-right of Singaporean politics, the People Action Party is ideologically conservative. The party has generally adopted liberal economic policies—favouring free market economics but has at times engaged in state interventionism. On social policy, it supports civic nationalism and communitarianism with a socially conservative approach. In foreign policy, it favours a strong military capability, serving as the guarantor of the country's independence due to its strategic position as a city-state.[12][13]

History

.jpg.webp)

Lee Kuan Yew, Toh Chin Chye and Goh Keng Swee were involved in the Malayan Forum, a London-based student activist group that was against colonial rule in Malaya in the 1940s and early 1950s.[14][15] Upon returning to Singapore, the group met regularly to discuss approaches to attain independence in Malayan territories and started looking for like-minded individuals to start a political party. Journalist S. Rajaratnam was introduced to Lee by Goh.[16] Lee was also introduced to several English-educated left-wing students and Chinese-educated union and student leaders while working on the Fajar sedition trial and the National Service riot case.[17]

Formation

The PAP was officially registered as a political party on 21 November 1954. Convenors of the party include a group of trade unionists, lawyers and journalists such as Lee Kuan Yew, Abdul Samad Ismail, Toh Chin Chye, Devan Nair, S. Rajaratnam, Chan Chiaw Thor, Fong Swee Suan, Tann Wee Keng and Tann Wee Tiong.[18] The political party was led by Lee Kuan Yew as its secretary-general, with Toh Chin Chye as its founding chairman. Other party officers include Tann Wee Tiong, Lee Gek Seng, Ong Eng Guan and Tann Wee Keng.[19]

The PAP first contested the 1955 general election in which 25 of 32 seats in the legislature were up for election. In this election, the PAP's four candidates gained much support from the trade union members and student groups such as the University Socialist Club, who canvassed for them.[20] The party won three seats, one by its leader Lee Kuan Yew for the Tanjong Pagar division and one by PAP co-founder Lim Chin Siong for the Bukit Timah division.[21][22] Then 22 years old unionist Lim Chin Siong was and remained the youngest Assemblyman ever to be elected to office. The election was won by the Labour Front headed by David Marshall.[23]

In April 1956, Lim and Lee represented the PAP at the London Constitutional Talks along with Chief Minister David Marshall which ended in failure as the British declined to grant Singapore internal self-government. On 7 June 1956, Marshall, disappointed with the constitutional talks, stepped down as Chief Minister as he had pledged to do so earlier if self-governance was not achieved. He was replaced by Lim Yew Hock, another Labour Front member.[24] Lim pursued a largely anti-communist campaign and managed to convince the British to make a definite plan for self-government. The Constitution of Singapore was revised accordingly in 1958, replacing the Rendel Constitution with one that granted Singapore self-government and the ability for its own population to fully elect its Legislative Assembly.

PAP and left-wing members who were communists were criticised for inciting riots in the mid-1950s.[25][26] Lim Chin Siong, Fong Swee Suan and Devan Nair as well as several unionists were detained by the police after the Chinese middle schools riots.[27] Lim Chin Siong was placed under solitary confinement for close to a year, away from his other PAP colleagues, as they were placed in the Medium Security Prison (MSP) instead.[28]

The number of PAP members imprisoned rose in August 1957, when PAP members from the trade unions (viewed as "communist or pro-communist") won half the seats in the CEC. The "moderate" CEC members, including Lee Kuan Yew, Toh Chin Chye and others, refused to take their appointments in the CEC. Yew Hock's government again made a sweeping round of arrests, imprisoning all the "communist" members, before the "moderates" re-assumed their office.[29]

Following this, the PAP decided to re-assert ties with the labour faction of Singapore in the hope of securing the votes of working-class Chinese Singaporeans, many of whom were supporters of the jailed unionists. Lee Kuan Yew convinced the incarcerated union leaders to sign documents to state their support for the party and its policies, promising to release the jailed members of the PAP when the party came to power in the next elections.[30] Ex-Barisan Sosialis member Tan Jing Quee claims that Lee was secretly in collusion with the British to stop Lim Chin Siong and the labour supporters from attaining power because of their huge popularity. Quee also states that Lim Yew Hock deliberately provoked the students into rioting and then had the labour leaders arrested.[31] Greg Poulgrain of Griffiths University argued that "Lee Kuan Yew was secretly a party with Lim Yew Hock in urging the Colonial Secretary to impose the subversives ban in making it illegal for former political detainees to stand for election".[31] Lee Kuan Yew eventually accused Lim Chin Siong and his supporters of being communists working for the Communist United Front, but evidence of Lim being a communist cadre was a matter of debate as many documents have yet to be declassified.[32][33]

First years in government

The PAP eventually won the 1959 general election under Lee Kuan Yew's leadership.[34] The election was also the first one to produce a fully elected parliament and a cabinet wielding powers of full internal self-government. The party has won a majority of seats in every general election since then. Lee, who became the first Prime Minister,[35] requested for the release of the PAP left-wing members to form the new cabinet.[36]

Great Split of 1961

In 1961, disagreements on the proposed merger plan to form Malaysia and long-standing internal party power struggle led to the split of the left-wing group from the PAP.[37][38][39]

Although the "Communist" faction had been frozen out of ever taking over the PAP, other problems had begun to arise internally. Ong Eng Guan, the former Mayor of the City Council after PAP's victory in the 1957 Singapore City Council election, presented a set of "16 Resolutions" to revisit some issues previously explored by Chin Siong's faction of the PAP: abolishing the PPSO, revising the Constitution, and changing the method of selecting cadre members.[40]:82

Although Ong's 16 Resolutions originated from the left-wing faction led by Lim Chin Siong, that faction had only reluctantly asked the PAP leadership to clarify its position on them,[41] as they still thought that the party with Lee Kuan Yew at the helm was a better alternative than Ong who was regarded as mercurial and a tyrant.[28] However, Lee took the stance taken by the left-wing PAP members as a lack of confidence in his leadership. This issue caused a rift between the "moderate" PAP members (led by Lee) and the "left-wing" faction (led by Lim).

Ong was then expelled, and he resigned his Assembly seat to challenge the government to a by-election in Hong Lim in April 1961, where he won 73.3% of the vote.[42] This was despite the fact that Lee Kuan Yew had made a secret alliance with Fong Chong Pik, the leader of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM), to get the CPM cadres to support the PAP in the by-election.[41]

Barisan Sosialis

The breakaway group of members formed the Barisan Sosialis with Lim Chin Siong as Secretary-General.[43] Aside from the Chinese union leaders, lawyers Thampoe Thamby Rajah and Tann Wee Tiong,[44] several members from the University Socialist Club such as James Puthucheary and Poh Soo Kai joined the party.[45] 35 of 51 branches of the PAP and 19 of 23 branch secretaries defected to Barisan.

Merger years 1963-1965

After gaining independence from Britain, Singapore joined the federation of Malaysia in 1963. Although the PAP was the ruling party in the state of Singapore, the PAP functioned as an opposition party at the federal level in the larger Malaysian political landscape. At that time and until the 2018 general election, the federal government in Kuala Lumpur was controlled by a coalition led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). However, the prospect that the PAP might rule Malaysia agitated UMNO. The PAP's decision to contest federal parliamentary seats outside Singapore and the UMNO decision to contest seats within Singapore breached an unspoken agreement to respect each other's spheres of influence and aggravated PAP–UMNO relations. The clash of personalities between PAP leader Lee Kuan Yew and Malaysian Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman resulted in a crisis and led to Rahman forcing Singapore to leave Malaysia on 9 August 1965. Upon independence, the nascent People's Action Party of Malaya, which had been registered in Malaysia on 10 March 1964, had its registration cancelled on 9 September 1965, just a month after Singapore's exit. Those with the now non-existent party applied to register People's Action Party, Malaya which was again rejected by the Malaysian government, before settling with the Democratic Action Party.

Post-independence, 1965 to present

The PAP has held an overwhelming majority of seats in the Parliament of Singapore since 1966, when the opposition Barisan Sosialis (Socialist Front) resigned from Parliament after winning 13 seats following the 1963 general election which took place months after a number of their leaders had been arrested in Operation Coldstore based on false charges of being communists.[31] It subsequently achieved a monopoly in an expanding parliament (winning every parliamentary seat) for the next four elections (1968, 1972, 1976 and 1980). Opposition parties returned to the legislature at a 1981 by-election. The 1984 general election was the first election in 21 years in which opposition parties won seats. From then until 2006, the PAP faced four opposition MPs at most. Opposition parties did not win more than four parliamentary seats from 1984 until 2011 when the Workers' Party won six seats and took away a Group Representation Constituency (GRC) for the first time for any opposition party. Even so, it still holds a supermajority in the legislature, to the point that Singapore is effectively a dominant party system.

Organisation

In its initial years, it adopted a traditionalist Leninist party organisation, together with a vanguard cadre from its labour-leaning faction in 1958, the PAP Executive later expelled the leftist faction, bringing the ideological basis of the party into the centre and later in the 1960s moving further to the right. In the beginning, there were about 500 so-called temporary cadre appointed,[46] but the current number of cadres is unknown and the register of cadres is kept confidential. In 1988, Wong Kan Seng revealed that there were more than 1,000 cadres. Cadre members have the right to attend party conferences and to vote for and elect and to be elected to the Central Executive Committee (CEC), the pinnacle of party leaders. To become a cadre, a party member is first nominated by the MP in his or her branch. The candidate then undergoes three sessions of interviews, each with four or five ministers or MPs and the appointment is then made by the CEC. About 100 candidates are nominated each year.[47]

Central Executive Committee and Secretary-General

Political power in the party is concentrated in the CEC, led by the Secretary-General. The Secretary-General of the PAP is the leader of the party. Because of the PAP electoral victories in every general election since 1959, the Prime Minister of Singapore has been by convention the Secretary-General of the PAP since 1959. Most CEC members are also cabinet members. From 1957 onwards, the rules laid down that the outgoing CEC should recommend a list of candidates from which the cadre members can then vote for the next CEC. This has been changed recently so that the CEC nominates eight members and the party caucus selects the remaining ten.

Historically, the position of Secretary-General was not considered for the post of Prime Minister, but rather the Central Executive Committee held an election to choose the Prime Minister. There was a contest between PAP Secretary-General Lee Kuan Yew and PAP treasurer Ong Eng Guan. Lee won the leadership and inaugurated the first Prime Minister of Singapore.[48]

Since that election, there is a tradition that Singapore's Prime Minister is the Secretary-General of the winning party with the majority of the seats.

HQ Executive Committee

The next lower level committee is the HQ Executive Committee (HQ Ex-Co) which performs the party's administration and oversees 12 sub-committees.[49] The sub-committees are the following:

- Branch Appointments and Relations

- Constituency Relations

- Information and Feedback

- New Media

- Malay Affairs

- Membership Recruitment and Cadre Selection

- PAP Awards

- Political Education

- Publicity and Publication

- Social and Recreational

- Women's Wing

- Young PAP

Two more were later added, totalling 14:

- 13. PAP Seniors Group (PAP.SG)

- 14. PAP Policy Forum (PPF)

Ideology

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

|

Since the early years of the PAP's rule, the idea of survival has been a central theme of Singaporean politics. According to Diane Mauzy and R. S. Milne, most analysts of Singapore have discerned four major ideologies of the PAP, namely pragmatism, meritocracy, multiracialism and Asian values or communitarianism.[50] In January 1991, the PAP introduced the White Paper on Shared Values which tried to create a national ideology and institutionalise Asian values. The party also says it has rejected what it considers Western-style liberal democracy despite the presence of many aspects of liberal democracy in Singapore's public policy such as the recognition of democratic institutions. Professor Hussin Mutalib opines that for Lee Kuan Yew "Singapore would be better off without liberal democracy".[51]

The party economic ideology has always accepted the need for some welfare spending, pragmatic economic interventionism and general Keynesian economic policy. However, free-market policies have been popular since the 1980s as part of the wider implementation of a meritocracy in civil society and Singapore frequently ranks extremely highly on indices of economic freedom published by economically liberal organisations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

Lee Kuan Yew also said in 1992: "Through Hong Kong watching, I concluded that state welfare and subsidies blunted the individual's drive to succeed. I watched with amazement the ease with which Hong Kong workers adjusted their salaries upwards in boom times and downwards in recessions. I resolved to reverse course on the welfare policies which my party had inherited or copied from British Labour Party policies".[52]

The party is deeply suspicious of communist political ideologies despite a brief joint alliance with the pro-labour co-founders of the PAP, who were accused of being communists, against colonialism in Singapore during the party's early years. In 2015, the party was seen by some observers to have adopted a left-of-centre tack in certain areas in order to remain electorally dominant.[53]

The socialism practised by the PAP during its first few decades in power was of a pragmatic kind as characterised by the party's rejection of nationalisation. According to Chan Heng Chee, by the late 1970s the intellectual credo of the government rested explicitly upon a philosophy of self-reliance, similar to the rugged individualism of the American brand of capitalism. Despite this, the PAP still claimed to be a socialist party, pointing out its regulation of the private sector, activist intervention in the economy and social policies as evidence of this.[54] In 1976, the PAP resigned from the Socialist International after the Dutch Labour Party had proposed to expel the party,[55] accusing it of suppressing freedom of speech.

The PAP symbol (which is red and blue on white) stands for action inside interracial unity. PAP members at party rallies have sometimes worn a uniform of white shirts and white trousers which symbolises purity of the party's ideologies of the government. The party also reminded that once the uniform is sullied, it would be difficult to make clean again.

At an Institute of Policy Studies dialogue held on 2 July 2015, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong spoke about the need to maintain a Jeffersonian natural aristocracy in the system to instill a culture of respect and to avoid anarchy.[56]

According to Kenneth Paul Tan, the PAP government has been able to amend the Constitution without much obstruction thanks to an overwhelming majority in Parliament, introducing multi-member constituencies, unelected parliamentary memberships and other institutional changes that have in effect strengthened the government's dominance and control of Parliament.[57] It has also propagated the idea that pragmatism and economic considerations triumph over accountability, transparency and checks and balances.[58] By drawing from a notion of Confucian values and Asian culture to construct ideological bulwarks like Asian democracy, the PAP government has been able to justify its liberal democracy deficit and authoritarian means.[57]

Central Committee Executive and Leadership

For many years, the party was led by former PAP Secretary-General Lee Kuan Yew, who was Prime Minister of Singapore from 1959 to 1990. Lee handed over the positions of Secretary-General and Prime Minister to Goh Chok Tong in 1991. The current Secretary-General of the PAP and Prime Minister of Singapore is Lee Hsien Loong, son of Lee Kuan Yew, who succeeded Goh Chok Tong on 12 August 2004.

The first chairman of the PAP was Toh Chin Chye. The current chairman of the PAP is Gan Kim Yong.[59]

List of Chairpersons

| Portrait | Name (birth– death) |

Term of office | Time in office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toh Chin Chye 杜进才Dù Jìn Cái (10 December 1921 – 3 February 2012) |

21 November 1954 | 5 January 1981 | 26 years, 45 days | |

|

Ong Teng Cheong 王鼎昌Wáng Dǐng Chāng (22 January 1936 – 8 February 2002) |

5 January 1981 | 16 August 1993 |

12 years, 223 days |

|

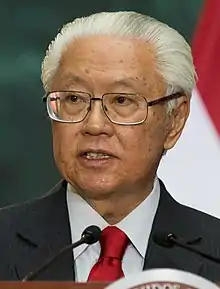

Tony Tan Keng Yam 陈庆炎Chén Qìng Yán (born 7 February 1940) |

1 September 1993 | 3 December 2004 | 11 years, 93 days |

|

Lim Boon Heng 林文兴Lín Wén Xìng (born 18 November 1947) |

3 December 2004 | 1 June 2011 | 6 years, 180 days |

|

Khaw Boon Wan 许文远Xǔ Wén Yuǎn (born 8 December 1952) |

1 June 2011 | 23 November 2018 | 7 years, 175 days |

.jpg.webp) |

Gan Kim Yong 颜金勇Yán Jīn Yǒng (born 9 February 1959) |

23 November 2018 | Incumbent | 2 years, 73 days |

List of Secretaries-General

| Portrait | Name (birth–death) |

Term of office | Time in office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Lee Kuan Yew 李光耀Lǐ Guāng Yào (16 September 1923 – 23 March 2015) |

21 November 1954 | 15 November 1992[60] | 37 years, 360 days |

|

Goh Chok Tong 吴作栋Wú Zuò Dòng (born 20 May 1941) |

15 November 1992[60] | 3 December 2004 | 12 years, 18 days |

|

Lee Hsien Loong 李显龙Lǐ Xiǎn Lóng (born 10 February 1952) |

3 December 2004 | Incumbent | 16 years, 63 days |

Central Executive Committee

As of 19 November 2020, the Central Executive Committee comprises 18 members, which were:

| Officer-holder | Name | Officer-holder | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secretary-General | Lee Hsien Loong | Chairman | Gan Kim Yong | Party Leader |

| Vice-Chairman | Masagos Zulkifli Bin Masagos Mohamad | Treasurer | K. Shanmugam | |

| Organizing Secretary | Grace Fu | Organizing Secretary | Desmond Lee | |

| Assistant Treasurer | Ong Ye Kung | 1st Assistant Secretary-General | Heng Swee Keat | |

| 2nd Assistant Secretary-General | Chan Chun Sing | Member | Alex Yam | |

| Member | Josephine Teo | Member | Edwin Tong | |

| Member | Indranee Thurai Rajah | Member | Lawrence Wong | |

| Member | Ng Chee Meng | Member | Tan Chuan Jin | |

| Member | Victor Lye | Member | Vivian Balakrishnan |

Office of the Mayors

| Officer-holder | Name | Officer-holder | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chairman of Mayors’ Committee and Mayor of South West District | Low Yen Ling | Mayor of Central Singapore District | Denise Phua | |

| Mayor of North East District | Desmond Choo | Mayor of North West District | Alex Yam | |

| Mayor of South East District | Mohd Fahmi Aliman |

Election results

Legislative Assembly

| Election | Seats up for election | Seats contested by party | Seats won by walkover | Contested seats won | Contested seats lost | Total seats won | Change | Total votes | Share of votes | Resulting government | Party leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1955 | 25 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 3 / 25 |

13,634 | 8.7% | Opposition | Lee Kuan Yew | |

| 1959 | 51 | 51 | 0 | 43 | 8 | 43 / 51 |

281,891 | 54.1% | Supermajority | ||

| 1963 | 51 | 51 | 0 | 37 | 14 | 37 / 51 |

272,924 | 46.9% | Supermajority |

- Legislative Assembly by-elections

| Election | Seats up for election | Seats contested by party | Contested seats won | Contested seats lost | Total votes | Share of votes | Outcome of election | Constituency contested | Party leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4,707 | 37.0% | 1 seat hold | Tanjong Pagar SMC | Lee Kuan Yew |

| 1961 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5,872 | 31.1% | 1 seat lost to Independent, 1 seat lost to WP | Anson SMC Hong Lim SMC | |

| 1965 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6,398 | 59.5% | 1 seat gained from UPP | Hong Lim SMC | |

Malaysian Parliament

| Election | Seats up for election | Seats contested by party | Seats won by walkover | Contested seats won | Contested seats lost | Total seats won | Change | Total votes | Share of votes | Resulting government | Party leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 104 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 1 / 144 |

42,130 | 2.0% | Opposition | Lee Kuan Yew |

Parliament

| Election | Seats up for election | Seats contested by party | Seats won by walkover | Contested seats won | Contested seats lost | Total seats won | Change | Total votes | Share of votes | Resulting government | Party leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | 58 | 58 | 51 | 7 | 0 | 58 / 58 |

65,812 | 86.7% | Won all seats | Lee Kuan Yew | |

| 1972 | 65 | 65 | 8 | 57 | 0 | 65 / 65 |

524,892 | 70.4% | Won all seats | ||

| 1976 | 69 | 69 | 16 | 53 | 0 | 69 / 69 |

590,169 | 74.1% | Won all seats | ||

| 1980 | 75 | 75 | 37 | 38 | 0 | 75 / 75 |

494,268 | 77.7% | Won all seats | ||

| 1984 | 79 | 79 | 30 | 47 | 2 | 77 / 79 |

568,310 | 64.8% | Supermajority | ||

| 1988 | 81 | 81 | 11 | 69 | 1 | 80 / 81 |

848,029 | 63.2% | Supermajority | ||

| 1991 | 81 | 81 | 41 | 36 | 4 | 77 / 81 |

477,760 | 61.0% | Supermajority | Goh Chok Tong | |

| 1997 | 83 | 83 | 47 | 34 | 2 | 81 / 83 |

465,751 | 65.0% | Supermajority | ||

| 2001 | 84 | 84 | 55 | 27 | 2 | 82 / 84 |

470,765 | 75.3% | Supermajority | ||

| 2006 | 84 | 84 | 37 | 45 | 2 | 82 / 84 |

748,130 | 66.6% | Supermajority | Lee Hsien Loong | |

| 2011 | 87 | 87 | 5 | 76 | 6 | 81 / 87 |

1,212,514 | 60.14% | Supermajority | ||

| 2015 | 89 | 89 | 0 | 83 | 6 | 83 / 89 |

1,576,784 | 69.86% | Supermajority | ||

| 2020 | 93 | 93 | 0 | 83 | 10 | 83 / 93 |

1,524,781 | 61.24% | Supermajority | ||

- Parliamentary by-elections

| Election | Seats up for election | Seats contested by party | Seats won by walkover | Contested seats won | Contested seats lost | Total votes | Share of votes | Outcome of election | Constituency contested | Party leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 9,082 | 82.9% | 7 seats gained from BS | Bukit Merah SMC Bukit Timah SMC Chua Chu Kang SMC Crawford SMC Joo Chiat SMC Jurong SMC Paya Lebar SMC |

Lee Kuan Yew |

| 1967 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 9,407 | 83.6% | 5 seats gained from BS | Bukit Panjang SMC Havelock SMC Jalan Kayu SMC Tampines SMC Thomson SMC | |

| 1970 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 14,545 | 69.9% | 5 seats hold | Delta SMC Havelock SMC Kampong Kapor SMC Ulu Pandan SMC Whampoa SMC | |

| 1979 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 53,222 | 72.7% | 7 seats hold | Anson SMC Geylang West SMC Mountbatten SMC Nee Soon SMC Potong Pasir SMC Sembawang SMC Telok Blangah SMC | |

| 1981 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6,359 | 47.1% | 1 seat lost to WP | Anson SMC | |

| 1992 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 48,965 | 72.9% | 4 seats hold | Marine Parade GRC | Goh Chok Tong |

| 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8,223 | 37.9% | No seat | Hougang SMC | Lee Hsien Loong |

| 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12,856 | 43.7% | 1 seat lost to WP | Punggol East SMC | |

| 2016 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 14,428 | 61.21% | 1 seat hold | Bukit Batok SMC | |

Internet presence

Since 1995, the youth wing of the PAP has had an internet presence "posting corrections to 'misinformation' about Singaporean politics or culture".[61] In February 2007, it was reported by The Straits Times that the PAP's new media committee chaired by minister Ng Eng Hen had initiated an effort to counter critics anonymously on the Internet "as it was necessary for the PAP to have a voice on cyberspace".[62] The initiative was divided by two sub-committees, one of which was in charge of strategising the campaigns and is co-headed by minister Lui Tuck Yew and MP Zaqy Mohamad. The other sub-committee new media capabilities group led by MPs Baey Yam Keng and Josephine Teo executed the strategies. The initiative was set up after the 2006 general election and also included around 20 IT-savvy PAP activists.[62]

See also

References

Citations

- Goldblatt, David (2005). Governance in the Asia-Pacific. Routledge. p. 293.

- Tan, Kenneth Paul (2016). Governing Global-City Singapore. Taylor & Francis. p. 91.

- Berger, Mark (2014). Rethinking the Third World. Macmillan. p. 98.

- Kuah-Pearce, Khun Eng (2010). Rebuilding the Ancestral Village. Hong Kong University Press. p. 37.

- Lim, Benny (18 January 2017). "Nation building reboot needed". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Singh, Bilveer (2017). Understanding Singapore Politics. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 36.

- Diane K. Mauzy and R.S. Milne (2002). Singapore Politics Under the People's Action Party. Routledge. p. 147. ISBN 0-415-24653-9.

- Rodan, Gary. "The Internet and Political Control in Singapore" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Reyes, Sebastian (29 September 2015). "Singapore's Stubborn Authoritarianism | Harvard Political Review". Harvard Political Review. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "A History of Singapore: Lion City, Asian Tiger". Discovery Channel. 2005.

- "SAF remains final guarantor of Singapore's independence". Singapore: Channel NewsAsia. 1 July 2007. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- "Lunch Talk on "Defending Singapore: Strategies for a Small State" by Minister for Defence Teo Chee Hean" (Press release). Ministry of Defence. 21 April 2005. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Desker, Barry; Guan, Chong; Kwa, Chong Guan (2012). Goh Keng Swee: A Public Career Remembered. World Scientific. ISBN 9789814291392.

- Josey, Alex (15 February 2013). Lee Kuan Yew: The Crucial Years. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. ISBN 9789814435499.

- Leong, Ching (2004). PAP 50 : Five Decades of the People's Action Party. Singapore: People's Action Party.

- Lee, Kuan Yew (15 September 2012). The Singapore Story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. ISBN 9789814561761.

- "Nine Form New Political Party in Singapore". The Straits Times. 24 October 1954. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "The PAP bosses". The Straits Times. 12 July 1955. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Yap, Sonny; Richard, Lim; Weng, K. Leong (2010). Men in White: The Untold Story of Singapore's Ruling Political Party.. ISBN. Singapore: Straits Times Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-9814266512.

- "Elected into the Legislative Assembly were (from left) …". National Archives of Singapore. 3 April 1955. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "The Results". The Straits Times. 3 April 1955. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Labour Wins - Marshal Will Be Chief Minister". Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Wong Hongyi (2009). "Lim Chin Siong". Singapore Infopedia. National Library Board Singapore. Archived from the original on 28 July 2009.

- "Mr. Lim Sits on The Fence". Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "The Guilty Men - By Goode". The Straits Times. 17 May 1955. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Who's Who - The Top 15 Names". The Straits Times. 28 October 1956. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Ministry of Finance (August 2015). "INCOME GROWTH, INEQUALITY AND MOBILITY TRENDS IN SINGAPORE" (PDF). Ministry of Finance Occasional Paper. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Leong, Weng Kam (10 June 2016). "Ex-PAP man recounts 1957 'kelong meeting'". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Chew, Melanie (29 July 2015). Leaders of Singapore. World Scientific. p. 80. ISBN 9789814719452.

- Tan Jing Quee (2001). Comet in our sky: Lim Chin Siong in history. Insan. ISBN 983-9602-14-4.

- migration (20 December 2014). "British archives, personal accounts, confirm extent of Communist United Front activities here: PM Lee". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "An annotated bibliography of Operation Coldstore - New Mandala". New Mandala. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- "2.45 am-PAP ROMPS HOME WITH LANDSLIDE VICTORY". The Straits Times. 31 May 1959. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "LEE IS PREMIER". Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Unlocking The Gates". The Straits Times. 3 June 1959. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- "When Lee lost control of PAP for 10 days". The Straits Times. 12 September 2009.

- "PAP 'rebels' to form an opposition party". Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Merger issue: Dr. Toh hits out at six top unionists". Archived from the original on 18 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James A. (2005). Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. Cambridge Press. pp. 8–10.

- Thum, Ping Tjin (November 2013). "'The Fundamental Issue is Anti-colonialism, Not Merger': Singapore's "Progressive Left", Operation Coldstore, and the Creation of Malaysia". ARI Working Paper (211).

- "Singapore Legislative Assembly By-Election April 1961 > Hong Lim". singapore-elections.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Poh, Soo K; Tan, Jing Quee; Koh, Kay Yew (2010). The Fajar Generation: The University Socialist Club and the Politics of Postwar Malaya and Singapore. Petaling Jaya: SIRD. pp. 59–60. ISBN 9789833782864.

- "Lawyers Rajah, Tann join Barisan Socialis". The Straits Times. 15 August 1961. Archived from the original on 30 August 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Loh, Kah S (2012). The University Socialist Club and the Contest for Malaya: Tangled Strands of Modernity. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-9089644091.

- Diane K. Mauzy and R.S. Milne (2002). Singapore Politics Under the People's Action Party. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 0-415-24653-9.

- Koh Buck Song (4 April 1998). "The PAP cadre system". The Straits Times. Singapore. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2006.

- "Lee Kuan Yew elected as Prime Minister of Singapore". AsiaOne. 10 September 2009. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "About the Leadership HQ Executive Committee". People's Action Party. Archived from the original on 6 May 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- Christopher Tremewan (1996). The Political Economy of Social Control in Singapore (St. Anthony's Series). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-312-15865-1.

- Hussin Mutalib (2004). Parties and Politics. A Study of Opposition Parties and the PAP in Singapore. Marshall Cavendish Adademic. p. 20. ISBN 981-210-408-9.

- Roger Kerr (9 December 1999). "Optimism for the New Millennium". Rotary Club of Wellington North. Archived from the original on 7 March 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2006.

- Azhar, Saeed; Chalmers, John (6 September 2015). "Singapore's rulers hope a nudge to the left will keep voters loyal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Driven by Growth: Political Change in the Asia-Pacific Region edited by James W. Morley

- "PAP bows out of Socialist International". Workers' Party of Singapore. June 1976. Archived from the original on 17 September 2007. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- "Unnatural aristocrats". The Economist. Archived from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Tan, Kenneth Paul (2012). "The Ideology of Pragmatism: Neo-liberal Globalisation and Political Authoritarianism in Singapore". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 42 (1): 67–92. doi:10.1080/00472336.2012.634644. S2CID 56236985.

- Tan, Kenneth Paul (2007). "Singapore's National Day Rally speech: A site of ideological negotiation". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 37 (3): 292–308. doi:10.1080/00472330701408635. S2CID 145405958.

- "PAP's new CEC". People's Action Party. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- "People's Action Party". Singapore Elections. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Mickey Unbound". Wired. 1 July 1995. Archived from the original on 10 February 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- Li Xueying (3 February 2007). "PAP moves to counter criticism of party, Govt in cyberspace". The Straits Times. Singapore.

Sources

- Books

- Goh, Cheng Teik (1994). Malaysia: Beyond Communal Politics. Pelanduk Publications. ISBN 967-978-475-4.

- Online sources

- "Singapore – People's Action Party" Archived 10 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Country Studies Series by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- James Chin, "The 2015 Singapore Swing: Depoliticised Polity and the Kiasi/Kiasu Voter" Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine. The Round Table, Vol. 105, Iss. 2, 2016. doi:10.1080/00358533.2016.1154383.

External links

| Library resources about People's Action Party |

| By People's Action Party |

|---|