Trumpism

Trumpism is a term for the political ideology, style of governance,[9] political movement and set of mechanisms for acquiring and keeping power that are associated with the 45th United States president, Donald Trump, and his political base.[10][11] It is an American political variant of the far-right[12][13] and of the national-populist and neo-nationalist sentiment seen in multiple nations worldwide in the late 2010s.[14]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Populism |

|---|

|

Ideologies and themes

Trumpism started its development predominantly during Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign. It denotes a populist political method that suggests nationalistic answers to political, economic, and social problems. These inclinations are refracted into such policy preferences as immigration restrictionism, trade protectionism, reluctance to enter into foreign entanglements, and opposition to entitlement reform.[15] As a political method, populism is not driven by any particular ideology.[16] Former National Security Advisor and former close Trump advisor John Bolton alleges this to be true about Trump, disputing that "Trumpism" even exists in any meaningful philosophical sense, emphasizing that "[t]he man does not have a philosophy. And people can try and draw lines between the dots of his decisions. They will fail."[17]

In the Routledge Handbook of Global Populism (2019), multiple co-authors note that populist leaders are instead pragmatic and opportunistic regarding themes, ideas and beliefs that strongly resonate with their followers.[18] Exit polling data suggests the campaign was successful at mobilizing the "white disenfranchised",[19] the lower- to working-class European-Americans who are experiencing growing social inequality and who often have stated opposition to the American political establishment. Ideologically, Trumpism has a right-wing populist accent.[20][21]

Trumpism differs from classical Abraham Lincoln Republicanism in many ways regarding free trade, immigration, equality, checks and balances in federal government, and the separation of church and state.[22] Peter J. Katzenstein of the WZB Berlin Social Science Center believes that Trumpism rests on three pillars, namely nationalism, religion and race.[9]

Historical background in America

.jpg.webp)

The roots of Trumpism in the United States can be traced to the Jacksonian era according to scholars Walter Russell Mead,[23] Peter Katzenstein[9] and Edwin Kent Morris.[24] Eric Rauchway says: "Trumpism — nativism and white supremacy — has deep roots in American history. But Trump himself put it to new and malignant purpose."[25]

The Jacksonians were often a xenophobic, "whites only" political movement.[23]

Andrew Jackson's followers felt he was one of them, enthusiastically supporting his defiance of politically correct norms of the nineteenth century and even constitutional law when they stood in the way of public policy popular among his followers. Jackson ignored the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Worcester v. Georgia and initiated the forced Cherokee removal from their treaty protected lands to benefit white locals at the cost of between 2,000 and 6,000 dead Cherokee men, women, and children. Notwithstanding such cases of Jacksonian inhumanity, Mead's view is that Jacksonianism provides the historical precedent explaining the movement of followers of Trump, marrying grass-roots disdain for elites, deep suspicion of overseas entanglements, and obsession with American power and sovereignty. Mead thinks this "hunger in America for a Jacksonian figure" drives followers towards Trump but cautions that historically "he is not the second coming of Andrew Jackson", observing that "his proposals tended to be pretty vague and often contradictory", exhibiting the common weakness of newly elected populist leaders, commenting early in his presidency that "now he has the difficulty of, you know, 'How do you govern?"[23]

Morris agrees with Mead, locating Trumpism's roots in the Jacksonian era from 1828 to 1848 under the presidencies of Jackson, Martin Van Buren and James K. Polk. On Morris's view, Trumpism also shares similarities with the post-World War I faction of the progressive movement which catered to a conservative populist recoil from the looser morality of the cosmopolitan cites and America's changing racial complexion.[24] In his book The Age of Reform (1955), historian Richard Hofstadter identified this faction's emergence when "a large part of the Progressive-Populist tradition had turned sour, became illiberal and ill-tempered."[26]

Prior to World War II, conservative themes of Trumpism were expressed in the America First movement in the early 20th century, and after World War II were attributed to a Republican Party faction known as the Old Right. By the 1990s, it became referred to as the paleoconservative movement, which according to Morris has now been re-branded as Trumpism.[27] Leo Löwenthal's book Prophets of Deceit (1949) summarized common narratives expressed in the post-World War II period of this populist fringe, specifically examining American demagogues of the period when modern mass media was married with the same destructive style of politics that historian Charles Clavey thinks Trumpism represents. According to Clavey, Löwenthal's book best explains the enduring appeal of Trumpism and offers the most striking historical insights into the movement.[28]

Writing in The New Yorker, journalist Nicholas Lemann states the post-war Republican Party ideology of fusionism, a fusion of pro-business party establishment with nativist, isolationist elements who gravitated towards the Republican and not the Democratic Party, later joined by Christian evangelicals "alarmed by the rise of secularism", was made possible by the Cold War and the "mutual fear and hatred of the spread of Communism."[29]

Championed by William F. Buckley Jr. and brought to fruition by Ronald Reagan in 1980, the fusion lost its glue with the collapse of the Soviet Union, which was followed by a growth of inequality and globalization that "created major discontent among middle and low income whites" within and without the Republican Party. After the 2012 United States presidential election saw the defeat of Mitt Romney by Barack Obama, the party establishment embraced an "autopsy" report, titled the Growth and Opportunity Project, which "called on the Party to reaffirm its identity as pro-market, government-skeptical, and ethnically and culturally inclusive." Ignoring the findings of the report and the party establishment in his campaign, Trump was "opposed by more officials in his own Party [...] than any Presidential nominee in recent American history", but at the same time he won "more votes" in the Republican primaries than any previous presidential candidate. By 2016, "people wanted somebody to throw a brick through a plate-glass window", in the words of political analyst Karl Rove.[29] His success in the party was such that an October 2020 poll found 58% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents surveyed considered themselves supporters of Trump rather than the Republican Party.[30]

Right-wing authoritarian populism

Michelle Goldberg, an opinion columnist for The New York Times, compares "the spirit of Trumpism" to classical fascist themes.[note 3] The "mobilizing vision" of fascism is of "the national community rising phoenix-like after a period of encroaching decadence which all but destroyed it", which "sounds a lot like MAGA" (Make America Great Again) according to Goldberg. Similarly, like the Trump movement, fascism sees a "need for authority by natural chiefs (always male), culminating in a national chieftain who alone is capable of incarnating the group's historical destiny." They believe in "the superiority of the leader's instincts over abstract and universal reason."[33]

George Will, another opinion writer, also notes similarities, both fascism and Trumpism being "a mood masquerading as a doctrine." National unity is based "on shared domestic dreads" -- for fascists the "Jews", for Trump the media ("enemies of the people"), "elites" and "globalists". Solutions come not from tedious "incrementalism and conciliation", but from the leader ("only I can fix it") unfettered by procedure. The political base is kept entertained with mass rallies, but inevitably the strongman develops a contempt for those he leads. Both are based on machismo, and in the case of Trumpism, "appeals to those in thrall to country-music manliness: 'We're truck-driving, beer-drinking, big-chested Americans too freedom-loving to let any itsy-bitsy virus make us wear masks.'"[34][note 4]

Christian Trumpism

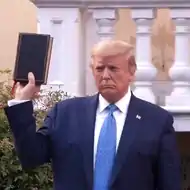

Theologian Michael Horton believes Christian Trumpism represents the confluence of three trends that have come together, namely Christian Americanism, end-times conspiracy and the prosperity gospel, with Christian Americanism being the narrative that God specially called the United States into being as an extraordinary if not miraculous providence and end-times conspiracy referring to the world's annihilation (figurative or literal) due to some conspiracy of nefarious groups and globalist powers threatening American sovereignty. Horton thinks that what he calls the "cult of Christian Trumpism" blends these three ingredients with "a generous dose of hucksterism, self-promotion and personality cult".[36]

Evangelical Christian and historian John Fea believes that "the church has warned against the pursuit of political power for a long, long time,", but that many modern day evangelicals such as Trump advisor and televangelist Paula White are ignoring these admonitions. Televangelist Jim Bakker praises prosperity gospel preacher White's ability to "walk into the White House at any time she wants to" and have "full access to the King." According to Fea, there are several other "court evangelicals" who have "devoted their careers to endorsing political candidates and Supreme Court justices who will restore what they believe to be the Judeo-Christian roots of the country" and who in turn are called on by Trump to "explain to their followers why Trump can be trusted in spite of his moral failings", including James Dobson, Franklin Graham, Johnnie Moore Jr., Ralph Reed, Gary Bauer, Richard Land, megachurch pastor Mark Burns and Southern Baptist pastor and Fox political commentator Robert Jeffress.[37] For prominent Christians who fail to support Trump, the cost is not a simple loss of presidential access but a substantial risk of a firestorm of criticism and backlash, a lesson learned by Timothy Dalrymple president of the flagship magazine of evangelicals Christianity Today and former chief editor Mark Galli who were condemned by over 200 evangelical leaders for co-authoring a letter arguing that Christians were obligated to support the impeachment of Trump.[38]

Historian Stephen Jaeger traces the history of admonitions against becoming beholden religious courtiers back to the 11th century, with warnings of curses placed on holy men barred from heaven for taking too "keen an interest in the affairs of the state."[39] Dangers to the court clergy were described by Peter of Blois, a 12th century French cleric, theologian and courtier who "knew that court life is the death of the soul"[40] and that despite participation at court being known to them to be "contrary to God and salvation", the clerical courtiers whitewashed it with a multitude of justifications such as biblical references of Moses being sent by God to the Pharoah.[41] Pope Pius II opposed the clergy's presence at court, believing it was very difficult for a Christian courtier to ""rein in ambition, suppress avarice, tame envy, strife, wrath, and cut off vice, while standing in the midst of these [very] things." The ancient history of such warnings of the dark corrupting influence of power over holy leaders is recounted by Fea who directly compares it to behavior of Trump's court evangelical leaders, warning that Christians are "in jeopardy of making idols out of political leaders by placing our sacred hopes in them."[42]

.jpg.webp)

Jeffress claims that evangelical leaders' support of Trump is moral regardless of behavior that Christianity today's chief editor called "a near perfect example of a human being who is morally lost and confused."[43] Jeffress argues that "the godly principle here is that governments have one responsibility, and that is Romans 13 [which] says to avenge evil doers."[44] This same biblical chapter was used by Jeff Sessions to claim biblical justification for Trump's policy of separating children from immigrant families. Historian Lincoln Muller explains this is one of two types of interpretations of Romans 13 which has been used in American political debates since its founding and is on the side of "the thread of American history that justifies oppression and domination in the name of law and order."[45] From Jeffress's reading, government's purpose is as a "strongman to protect its citizens against evildoers", adding: "I don't care about that candidate's tone or vocabulary, I want the meanest toughest son a you-know-what I can find, and I believe that is biblical."[46] Jeffress traces this Christian libertarian perspective on government's sole role to suppress evil back to Saint Augustine who argued in The City of God against the Pagans (426 CE) that government's role is to restrain evil so that Christians can peacefully practice their beliefs. Martin Luther similarly believed that government should be limited to checking sin.[47]

Like Jeffress, Richard Land refused to cut ties with Trump after his reaction to the Charlottesville white supremacist rally, with the explanation that "Jesus did not turn away from those who may have seemed brash with their words or behavior", adding that "now is not the time to quit or retreat, but just the opposite – to lean in closer."[48] Johnnie Moore's explanation for refusing to repudiate Trump after his Charlottesville response was that "you only make a difference if you have a seat at the table."[49] Trinity Forum fellow Peter Wehner warns that "[t]he perennial danger facing Christians is seduction and self-delusion. That's what's happening in the Trump era. The president is using evangelical leaders to shield himself from criticism."[50] Evangelical biblical scholar Ben Witherington believes that Trump's evangelical apologists' defensive use of the tax collector comparison is false and that retaining a "seat at the table" is only supportable if the Christian leader is admonishing the President to reverse course, explaining that "[t]he sinners and tax collectors were not political officials, so there is no analogy there. Besides, Jesus was not giving the sinners and tax collectors political advice—he was telling them to repent! If that's what evangelical leaders are doing with our President, and telling him when his politics are un-Christian, and explaining to him that racism is an enormous sin and there is no moral equivalency between the two sides in Charlottesville, then well and good. Otherwise, they are complicit with the sins of our leaders."[50]

Evangelical Bible studies author Beth Moore joins in criticism of the perspective of Trump's evangelicals, writing: "I have never seen anything in these United States of America I found more astonishingly seductive and dangerous to the saints of God than Trumpism. This Christian nationalism is not of God. Move back from it." Moore warns that "we will be held responsible for remaining passive in this day of seduction to save our own skin while the saints we've been entrusted to serve are being seduced, manipulated, USED and stirred up into a lather of zeal devoid of the Holy Spirit for political gain." Moore's view is that "[w]e can't sanctify idolatry by labeling a leader our Cyrus. We need no Cyrus. We have a king. His name is Jesus."[51] Presbyterian minister and Pulitzer prize winning author Chris Hedges thinks many of Trump's white evangelical supporters resemble those of the German Christians movement of 1930s Germany who also regarded their leader in an idolatrous way, the Christo-fascist idea of a Volk messiah, a leader who would act as an instrument of God to restore their country from moral depravity to greatness.[38][note 5] Also rejecting the idolatry, John Fea stated that "Trump takes everything that Jesus taught, especially in the Sermon on the Mount, throws it out the window, exchanges it for a mess of pottage called 'Make America Great Again', and from a Christian perspective for me, that borders on — no, it is a form of idolatry."[52]

Theologian Greg Boyd challenges the religious right's politicization of Christianity, and the Christian nationalist theory of American exceptionalism, charging that "a significant segment of American evangelicalism is guilty of nationalistic and political idolatry." Boyd compares the cause of "taking America back for God" and policies to force Christian values through political coercion to the aspiration in first century Israel to "take Israel back for God" which caused followers to attempt to fit Jesus into the role of a political messiah. Boyd argues that Jesus declined, demonstrating that "God's mode of operation in the world was no longer going to be nationalistic." Boyd asks to consider Christ's example, asking questions such as whether Jesus ever suggested by word or example that Christians should aspire to gaining power in the reigning government of the day, or whether he advocated using civil laws to change the behavior of sinners. Like Fea, Boyd states he is not making the argument of passive political non involvement, writing that "of course our political views will be influenced by our Christian faith" but rather that we must embrace humility and not "christen our views as 'the' Christian view." This humility in Boyd's view requires Christians to reject social domination, the "'power over' others to acquire and secure these things," and that "the only way we individually and collectively represent the kingdom of God is through loving, Christ like, sacrificial acts of service to others. Anything and everything else, however good and noble, lies outside the kingdom of God."[54] Horton thinks that rather than engage in what he calls the cult of "Christian Trumpism", Christians should reject turning the "saving gospel into a worldly power".[36] Fea thinks that the Christian response to Trump should instead be those used in the civil rights movement, namely preaching hope not fear; humility, not power to socially dominate others; and responsible reading of history as in Martin Luther King Jr.'s Letter from Birmingham Jail rather than nostalgia for a prior American Christian utopia that never was.[55]

Emma Green in The Atlantic blamed pro-Trump, evangelical white Christians and the Jericho March participants for the storming of the Capitol building on January 6, 2021, saying: "The mob carried signs and flag declaring 'Jesus saves!' and 'God, guns & guts made America, let's keep all three'."[56]

Foreign policy

In terms of foreign policy in the sense of Trump's "America First", unilateralism is preferred to a multilateral policy and national interests are particularly emphasized, especially in the context of economic treaties and alliance obligations.[57][58] Trump has shown a disdain for traditional American allies such as Canada as well as transatlantic partners NATO and the European Union.[59][60] Conversely, Trump has shown sympathy for autocratic rulers, especially for the Russian president Vladimir Putin, whom Trump often praised even before taking office,[61] and during the 2018 Russia–United States summit.[62] The "America First" foreign policy includes promises by Trump to end American involvement in foreign wars, notably in the Middle East, while also issuing tighter foreign policy through sanctions against Iran, among other countries.[63][64]

Economic policy

In terms of economic policy, Trumpism "promises new jobs and more domestic investment."[65] Trump's hard line against export surpluses of American trading partners has led to a tense situation in 2018 with mutually imposed punitive tariffs between the United States on the one hand and the European Union and China on the other.[66] Trump secures the support of his political base with a policy that strongly emphasizes nationalism and criticism of globalization.[67]

Non-ideological aspects

Journalist Elaina Plott suggests ideology is not as important as other characteristics of Trumpism.[note 6] Plott cites political analyst Jeff Roe, who observed Trump "understood" and acted on the trend among Republican voters to be "less ideological" but "more polarized". Republicans are now more willing to accept policies like government mandated health care coverage for pre-existing conditions or trade tariffs, formerly disdained by conservatives as burdensome government regulations. At the same time, strong avowals of support for Trump and aggressive partisanship have become part of Republican election campaigning -- in at least some parts of America -- reaching down even to non-partisan campaigns for local government which formerly were collegial and issue-driven.[68] Research by political scientist Marc Hetherington and others has found Trump supporters tend to share a "worldview" transcending political ideology, agreeing with statements like "the best strategy is to play hardball, even if it means being unfair." In contrast, those who agree with statements like "cooperation is the key to success" tend to prefer Trump's adversary Mitt Romney.[68]

Journalist Nicholas Lemann notes the disconnect between some of the Trump campaign rhetoric and promises (anti-free-trade nationalism, defense of Social Security, attacks on big business, "building that big, beautiful wall and making Mexico pay for it", repealing Obama's Affordable Care Act, a trillion dollar infrastructure-building program) on the one hand, and the "conventional" Republican policies and legislation enacted by the Trump administration (substantial tax cuts, rollbacks of federal regulations, and increases in military spending), on the other.[29] Many have noted that instead of the Republican National Convention issuing the customary "platform" of policies and promises for the 2020 campaign, it offered a "one-page resolution" stating that the party was not "going to have a new platform, but instead [...] 'has and will continue to enthusiastically support the president's America-first agenda.'"[note 7][69]

Methods of persuasion

Sociologist Arlie Hochschild thinks that emotional themes in Trump’s rhetoric are fundamental, writing that "Trump’s "speeches—evoking dominance, bravado, clarity, national pride, and personal uplift—inspire an emotional transformation," deeply resonating with their "emotional self-interest". Hoschild's perspective is that Trump is best understood as an "emotions candidate," arguing that comprehending the emotional self-interests of voters explains the paradox of the success of such politicians raised by Thomas Frank’s book What’s the Matter with Kansas?, an anomaly which motivated her five year immersive research into the emotional dynamics of the Tea Party movement which she believes has mutated into Trumpism.[70][71] The book resulting from her research, Strangers in Their Own Land, was named one of the "6 books to understand Trump’s Win" by the New York Times.[72] Hochschild claims it is wrong for progressives to assume that well educated individuals have mainly been persuaded by political rhetoric to vote against their rational self interest through appeals to the "’bad angels’ of their nature—their greed, selfishness, racial intolerance, homophobia, and desire to get out of paying taxes that go to the unfortunate." She grants that the appeal to bad angels are made by Trump, but that it "obscures another—to the right wing’s good angels—their patience in waiting in line in scary economic times, their capacity for loyalty, sacrifice, and endurance", qualities she describes as a part of a motivating narrative she calls their "deep story", a social contract narrative that appears to be widely shared in other countries as well.[73] She thinks Trump’s rhetoric achieves group cohesiveness among his followers by exploiting a crowd phenomenon Emile Durkheim called "collective effervescence", "a state of emotional excitation felt by those who join with others they take to be fellow members of a moral or biological tribe... to affirm their unity and, united, they feel secure and respected."[74]

Rhetorically, Trumpism employs absolutist framings and threat narratives[75] characterized by a rejection of the political establishment.[76] The absolutist rhetoric emphasizes non-negotiable boundaries and moral outrage at their supposed violation.[77][note 8] The rhetorical pattern within a Trump rally is common for authoritarian movements. First, elicit a sense of depression, humiliation and victimhood. Second, separate the world into two opposing groups: a relentlessly demonized set of others versus those who have the power and will to overcome them.[80] This involves vividly identifying the enemy supposedly causing the current state of affairs and then promoting paranoid conspiracy theories to inflame fear and anger. After cycling these first two patterns through the populace, the final message aim to produce a cathartic release of pent-up mob energy, with a promise that salvation is at hand because there is a powerful leader who will deliver the nation back to its former glory.[81]

This three-part pattern was first identified in 1932 by Roger Money-Kyrle and later published in his Psychology of Propaganda.[82] A constant barrage of sensationalistic rhetoric serves to rivet media attention while achieving multiple political objectives, not the least of which is that it serves to obscure actions such as profound neoliberal deregulation. One study gives the example that significant environmental deregulation occurred, but escaped much media attention, during the first year of the Trump administration due to its concurrent use of spectacular racist rhetoric. According to the authors, this served political objectives of dehumanizing its targets, eroding democratic norms, and consolidating power by emotionally connecting with and inflaming resentments among the base of followers, but most importantly it served to distract media attention from deregulatory policymaking by igniting intense media coverage of the distractions, precisely due to their radically transgressive nature.[83]

From the perspective of political science scholar Andrea Schneiker, Trump's skill with personal branding allowed him to effectively market himself as this restorative decisive leader by leveraging his celebrity status and name recognition. "Just like Superman, Spiderman or James Bond, the superhero that is marketed by Donald Trump is an ordinary citizen that, in case of an emergency, uses his superpowers to save others, that is, his country. He sees a problem, knows what has to be done in order to solve it, has the ability to fix the situation and does so. According to the branding strategy of Donald Trump... a superhero is needed to solve the problems of ordinary Americans and the nation as such, because politicians are not able to do so. Hence, the superhero per definition is an anti-politician. Due to his celebrity status and his identity as entertainer,[84] Donald Trump can thereby be considered to be allowed to take extraordinary measures and even to break rules."[85]

According to civil-rights lawyer Burt Neuborne and political theorist William E. Connolly, Trumpist rhetoric employs tropes similar to those used by fascists in Germany[86] to persuade citizens (at first a minority) to give up democracy, by using a barrage of falsehoods, half-truths, personal invective, threats, xenophobia, national-security scares, religious bigotry, white racism, exploitation of economic insecurity, and a never-ending search for scapegoats.[87] Neuborne found twenty parallel practices,[88] such as creating what amounts to an "alternate reality" in adherents' minds, through direct communications, by nurturing a fawning mass media and by deriding scientists to erode the notion of objective truth;[89] organizing carefully orchestrated mass rallies;[90] bitterly attacking judges when legal cases are lost or rejected;[91] using an uninterrupted stream of lies, half-truths, insults, vituperation and innuendo designed to marginalize, demonize and eventually destroy opponents;[90] making jingoistic appeals to ultranationalist fervor;[90] and promising to slow, stop and even reverse the flow of "undesirable" ethnic groups who are cast as scapegoats for the nation's ills.[92]

Connolly presents a similar list in his book Aspirational Fascism (2017), adding comparisons of the integration of theatrics and crowd participation with rhetoric, involving grandiose bodily gestures, grimaces, hysterical charges, dramatic repetitions of alternate reality falsehoods, and totalistic assertions incorporated into signature phrases that audiences are strongly encouraged to join in chanting.[93] Despite the similarities, Connolly stresses that Trump is no Nazi but "is rather, an aspirational fascist who pursues crowd adulation, hyperaggressive nationalism, white triumphalism, and militarism, pursues a law-and-order regime giving unaccountable power to the police, and is a practitioner of a rhetorical style that regularly creates fake news and smears opponents to mobilize support for the Big Lies he advances."[86]

.jpg.webp)

Reporting on the crowd dynamics of Trumpist rallies has documented expressions of the Money-Kyrle pattern and associated stagecraft,[94][95] with some comparing the symbiotic dynamics of crowd pleasing to that of the sports entertainment style of events which Trump was involved with since the 1980s.[96][97] Connolly thinks that the performance draws energy from the crowd's anger as it channels it, drawing it into a collage of anxieties, frustrations and resentments about malaise themes, such as deindustrialization, offshoring, racial tensions, political correctness, a more humble position for the United States in global security, economics and so on. Connolly observes that animated gestures, pantomiming, facial expressions, strutting and finger pointing are incorporated as part of the theater, transforming the anxiety into anger directed at particular targets, concluding that "each element in a Trump performance flows and folds into the others until an aggressive resonance machine is formed that is more intense than its parts."[98]

Some academics point out that the narrative common in the popular press describing the psychology of such crowds is a repetition of a 19th-century theory by Gustave Le Bon when organized crowds were seen by political elites as potentially anarchic threats to the social order. In his book The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895), Le Bon described a sort of collective contagion uniting a crowd into a near religious frenzy, reducing members to barbaric, if not subhuman levels of consciousness with mindless anarchic goals.[99] Since such a description depersonalizes supporters, this type of Le Bon analysis is criticized because the would-be defenders of liberal democracy simultaneously are dodging responsibility for investigating grievances while also unwittingly accepting the same us vs. them framing of illiberalism.[100][101] Connolly acknowledges the risks but considers it more risky to ignore that Trumpian persuasion is successful due to deliberate use of techniques evoking more mild forms of affective contagion.[102]

The absolutist rhetoric employed heavily favors crowd reaction over veracity, with a large number of false - or at least misleading - statements which Trump presents as facts.[103] Unlike conventional lies of politicians exaggerating their accomplishments, Trump's lies are egregious, making lies about easily verifiable facts. At one rally Trump stated his father "came from Germany", even though Fred Trump was born in New York City. His lying is not new, as Trump told The New York Times to be Swedish in 1976. At a Michigan rally in December 1990, Trump presented 179 statements as fact, more than one a minute and 67 percent of them were false or misleading. Trump is not shy about lying to more sophisticated audiences, but he is surprised when crowd reaction is not what he expected, as was the case when leaders at the 2018 United Nations General Assembly burst into laughter at his boast that he had accomplished more in his first two years than any other United States president. Visibly startled, Trump responded to the audience: "I didn't expect that reaction."[104] Trump lies about the trivial, claiming that there was no rain on the day of his inauguration when in fact it did rain, making the grandiose Big Lies such as claiming that Obama founded ISIS, or promoting the birther movement, a conspiracy theory believing Obama was born in Kenya, not Hawaii.[105] Connolly points to the similarities of such reality bending statements with fascist and post Soviet techniques of propaganda including Kompromat (scandalous material), stating that "Trumpian persuasion draws significantly upon the repetition of Big Lies."[106]

On January 31, 2021, a detailed overview of the attempt to subvert the election of the United States was published in The New York Times.[107][108]

Social psychology

Dominance orientation

.jpg.webp)

Social psychology research into the Trump movement, such as that of Bob Altemeyer, Thomas F. Pettigrew, and Karen Stenner, views the Trump movement as primarily being driven by the psychological predispositions of its followers.[11][109][110] Altemeyer and other researchers such as Pettigrew emphasize that no claim is made that these factors provide a complete explanation, mentioning other research showing that important political and historical factors (reviewed elsewhere in this article) are also involved.[110] In a non-academic book which he co-authored with John Dean entitled Authoritarian Nightmare: Trump and His Followers, Altemeyer describes research which demonstrates that Trump followers have a distinguishing preference for strongly hierarchical and ethnocentric social orders that favor their in-group.[note 9] Despite disparate and inconsistent beliefs and ideologies, a coalition of such followers can become cohesive and broad in part because each individual "compartmentalizes" their thoughts[112] and they are free to define their sense of the threatened tribal in-group[113] in their own terms, whether it is predominantly related to their cultural or religious views[114] (e.g. the mystery of evangelical support for Trump), nationalism[115] (e.g. the Make America Great Again slogan), or their race (maintaining a white majority).[116]

Altemeyer, Macwilliams, Feldman, Choma, Hancock, Van Assche and Pettigrew claim that instead of directly attempting to measure such ideological, racial or policy views, supporters of such movements can be reliably predicted by using two social psychology scales (singly or in combination), namely right-wing authoritarian (RWA) measures which were developed in the 1980s by Altemeyer and other authoritarian personality researchers, and the social dominance orientation (SDO) scale developed in the 1990s by social dominance theorists. In May 2019, Monmouth University Polling Institute conducted a study in collaboration with Altemeyer in order to empirically test the hypothesis using the SDO and RWA measures. The finding was that social dominance orientation and affinity for authoritarian leadership are indeed highly correlated with followers of Trumpism.[117] Altemeyer's perspective and his use of an authoritarian scale and SDO to identify Trump followers is not uncommon. His study was a further confirmation of the earlier mentioned studies discussed in MacWilliams (2016), Feldman (2020), Choma and Hancock (2017), and Van Assche & Pettigrew (2016).[118]

The research does not imply that the followers always behave in an authoritarian manner but that expression is contingent, which means that there is reduced influence if it is not triggered by fear and threats.[109][119][120] The research is global and similar social psychological techniques for analyzing Trumpism have demonstrated their effectiveness at identifying adherents of similar movements in Europe, including those Belgium and France (Lubbers & Scheepers, 2002; Swyngedouw & Giles, 2007; Van Hiel & Mervielde, 2002; Van Hiel, 2012), the Netherlands (Cornelis & Van Hiel, 2014) and Italy (Leone, Desimoni & Chirumbolo, 2014).[121] Quoting comments from participants in a series of focus groups made up of people who had voted for Democrat Obama in 2012 but flipped to Trump in 2016, pollster Diane Feldman noted the anti-government, anti-costal-élite anger: "'They think they're better than us, they're P.C., they're virtue-signallers.' '[Trump] doesn't come across as one of those people who think they're better than us and are screwing us.' 'They lecture us.' 'They don't even go to church.' 'They're in charge, and they're ripping us off.'"[29]

Collective narcissism

Cultural anthropologist Paul Stoller thinks Trump masterfully employed the fundamentals of celebrity culture-glitz, illusion and fantasy to construct a shared alternate reality where lies become truth and reality's resistance to one's own dreams are overcome by the right attitude and bold self-confidence.[123] Trump's father indoctrinated his children from an early age into the sort of positive thinking approach to reality advocated by the family's pastor Norman Vincent Peale.[124] Trump boasted that Peale considered him the greatest student of his philosophy that regards facts as not important, because positive attitudes will instead cause what you "image" to materialize.[125] Trump biographer Gwenda Blair thinks Trump took Peale's self-help philosophy and "weaponized it."[126]

Robert Jay Lifton, a scholar of psychohistory and authority on the nature of cults, emphasizes the importance of understanding Trumpism "as an assault on reality." A leader has more power if he is in any part successful at making truth irrelevant to his followers.[127] Trump biographer Timothy L. O'Brien agrees, stating: "It is a core operating principle of Trumpism. If you constantly attack objective reality, you are left as the only trustworthy source of information, which is one of his goals for his relationship with his supporters — that they should believe no one else but him."[128] Lifton believes Trump is a purveyor of a solipsistic reality[129] which is hostile to facts and is made collective by amplifying frustrations and fears held by his community of zealous believers. Social psychologists refer to this as collective narcissism, a commonly held and strong emotional investment in the idea that one's group has a special status in society. It is often accompanied by chronic expressions of intolerance towards out-groups, intergroup aggression and frequent expressions of group victimhood whenever the in-group feels threatened by perceived criticisms or lack of proper respect for the in-group.[130] Identity of group members is closely tied to the collective identity expressed by its leader,[131] motivating multiple studies to examine its relationship to authoritarian movements. Collective narcissism measures have been shown to be a powerful predictor of membership in such movements including Trump's.[132]

Although the leader possesses dominant ownership of the reality shared by the group, Lifton sees important differences between Trumpism and typical cults, such as not advancing a totalist ideology and that isolation from the outside world is not used to preserve group cohesion. Lifton does identify multiple similarities with the kinds of cults disparaging the fake world that outsiders are deluded by in preference for their true reality- a world that transcends the illusions and false information created by the cult's titanic enemies. Persuasion techniques similar to those of cults are used such as indoctrination employing constant echoing of catch phrases (via rally response, retweet, or Facebook share), or in participatory response to the guru's like utterances either in person or in online settings. Examples include the use of call and response ("Clinton" triggers "lock her up"; "immigrants" triggers "build that wall"; "who will pay for it?" triggers "Mexico"), thereby deepening the sense of participation with the transcendent unity between the leader and the community.[133] Participants and observers at rallies have remarked on the special kind of liberating feeling that is often experienced which Lifton calls a "high state" that "can even be called experiences of transcendence."[134]

Conservative culture commentator David Brooks observes that under Trump, this post-truth mindset heavily reliant on conspiracy themes came to dominate Republican identity, providing its believers a sense of superiority since such insiders possess important information most people do not have.[135] This results in an empowering sense of agency[136] with the liberation, entitlement and group duty to reject "experts" and the influence of hidden cabals seeking to dominate them.[135] Social media amplify the power of members to promote and expand their connections with like minded believers in insular alternate reality echo chambers.[137] Social psychology and cognitive science research shows that individuals seek information and communities that confirm their views and that even those with critical thinking skills sufficient to identify false claims with non political material cannot do so when interpreting factual material that does not conform to political beliefs.[note 10] While such media-enabled departures from shared, fact-based reality dates at least as far back as 1439 with the appearance of the Gutenberg press,[139] what is new about social media is the personal bond created through direct and instantaneous communications from the leader, and the constant opportunity to repeat the messages and participate in the group identity signaling behavior. Prior to 2015, Trump already had firmly established this kind of parasocial bond with a substantial base of followers due to his repeated television and media appearances. For those sharing political views similar to his, Trump's use of Twitter to share his conspiratorial views caused those emotional bonds to intensify, causing his supporters to feel a deepened empathetic bond as with a friend- sharing his anger, sharing his moral outrage, taking pride in his successes, sharing in his denial of failures and his oftentimes conspiratorial views.[140]

Given conspiracy theories' effectiveness as an emotional tool, Brooks thinks that such sharing of conspiracy theories has become the most powerful community bonding mechanism of the 21st century.[135] Conspiracy theories usually have a strong political component[141] and books such as Hofstadter's The Paranoid Style in American Politics describe the political efficacy of these alternate takes on reality. Some attribute Trump's political success to making such narratives a regular staple of Trumpist rhetoric, such as the purported rigging of the 2016 election to defeat Trump, that climate change is a hoax perpetrated by the Chinese, that Obama was not born in the United States, multiple conspiracy theories about the Clintons, that vaccines cause autism and so on.[142] One of the most popular though disproven and discredited conspiracy theories is Qanon which asserts that top Democrats run an elite child sex-trafficking ring and that President Trump is making efforts to dismantle it. An October 2020 Yahoo-YouGov poll showed that these Qanon claims are mainstream, not fringe beliefs among Trump supporters, with both elements of the theory said to be true by fully half of Trump supporters polled.[143][144]

.jpg.webp)

Some social psychologists see the predisposition of Trumpists towards interpreting social interactions in terms of dominance frameworks as extending to their relationship towards facts. A study by Felix Sussenbach and Adam B. Moore found that the dominance motive strongly correlated with hostility towards disconfirming facts and affinity for conspiracies among 2016 Trump voters but not among Clinton voters.[145] Many critics note Trump's skill in exploiting narrative, emotion, and a whole host of rhetorical ploys to draw supporters into the group's common adventure[146] as characters in a story much bigger than themselves.[147] It is a story that involves not just a community-building call to arms to defeat titanic threats,[75] or of the leader's heroic deeds restoring American greatness, but of a restoration of each supporter's individual sense of liberty and power to control their lives.[148] Trump channels and amplifies these aspirations, explaining in one of his books that his bending of the truth is effective because it plays to people's greatest fantasies.[149] By contrast, Clinton was dismissive of such emotion-filled storytelling and ignored the emotional dynamics of the Trumpist narrative.[150]

Reception

.jpg.webp)

Trumpism has been likened to Machiavellianism and to Mussolini's fascism.[151][152][153][154][155][156][157]

American historian Robert Paxton poses the question as to whether Trumpism is fascism or not. Instead, Paxton believes that it bears a greater resemblance to a plutocracy, a government which is controlled by a wealthy elite.[158] However, Paxton changed his opinion following the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol and argued that it is "not just acceptable but necessary" to understand Trumpism as a form of fascism.[159] Sociology professor Dylan John Riley calls Trumpism "neo-Bonapartist patrimonialism". British historian Roger Griffin considers the definition of fascism unfulfilled because Trump does not question the politics of the United States and he also does not want to outright abolish its democratic institutions.[160]

Argentine historian Federico Finchelstein believes that significant intersections exist between Peronism and Trumpism because their mutual disregard for the contemporary political system (both in the area of domestic and foreign policy) is discernible.[161] American historian Christopher Browning considers the long-term consequences of Trump's policies and the support which he receives for them from the Republican Party to be potentially dangerous for democracy.[162] In the German-speaking debate, the term has so far only appeared sporadically, mostly in connection with the crisis of confidence in politics and the media. It then describes the strategy of mostly right-wing political actors who wish to stir up this crisis in order to profit from it.[163] The British Collins English Dictionary named Trumpism, after Brexit, one of its "Words of the Year 2016"; the term, in their definition, denotes both Trump's ideology and his characteristic way of speaking.[164]

In How to Lose a Country: The 7 Steps from Democracy to Dictatorship, Turkish author Ece Temelkuran describes Trumpism as echoing a number of views and tactics which were expressed and used by the Turkish politician Recep Tayyip Erdoğan during his rise to power. Some of these tactics and views are right-wing populism; demonization of the press; subversion of well-established and proven facts (both historical and scientific); dismantling judicial and political mechanisms; portraying systematic issues such as sexism or racism as isolated incidents; and crafting an "ideal" citizen.[165]

Political scientist Mark Blyth and his colleague Jonathan Hopkin believe that strong similarities exist between Trumpism and similar movements towards illiberal democracies worldwide, but they do not believe that Trumpism is a movement which is merely being driven by revulsion, loss, and racism. Hopkin and Blyth argue that on both the right and the left the global economy is driving the growth of neo-nationalist coalitions which find followers who want to be free of the constraints which are being placed on them by establishment elites whose members advocate neoliberal economics and globalism.[166] Others emphasize the lack of interest in finding real solutions to the social malaise which have been identified, and they also believe that those individuals and groups who are executing policy are actually following a pattern which has been identified by sociology researchers like Leo Löwenthal and Norbert Guterman as originating in the post-World War II work of the Frankfurt School of social theory. Based on this perspective, books such as Löwenthal and Guterman's Prophets of Deceit offer the best insights into how movements like Trumpism dupe their followers by perpetuating their misery and preparing them to move further towards an illiberal form of government.[28]

Trumpism in other countries

Canada

According to Global News, Maclean's magazine, the National Observer, Toronto Star,[167][168] and The Globe and Mail, there is Trumpism in Canada.[169][170][171][172] In a November 2020 interview on The Current, immediately following the 2020 US elections, law professor Allan Rock, who served as Canada's attorney general and as Canada's ambassador to the U.N., described Trumpism and its potential impact on Canada.[173] Rock said that even with Trump losing the election, he had "awakened something that won't go away". He said it was something "we can now refer to as Trumpism"—a force that he has "harnessed" Trump has "given expression to an underlying frustration and anger, that arises from economic inequality, from the implications from globalisation."[173] Rock cautioned that Canada must "keep up its guard against the spread of Trumpism[167] which he described as "destabilizing", "crude", "nationalistic", "ugly", "divisive", "racist", and "angry".[173] Rock added that one measurable impact on Canada of the "overtly racist behaviour" associated with Trumpism is that racists and white supremacists have become emboldened since 2016, resulting in a steep increase in the number of these organizations in Canada and a shockingly high increase in the rate of hate crimes in 2017 and 2018 in Canada.[173]

Maclean's and the Star, cited the research of Frank Graves who has been studying the rise of populism in Canada for a number of years. In a June 30, 2020 School of Public Policy journal article, he co-authored, the authors described a decrease in trust in the news and in journalists since 2011 in Canada, along with an increase in skepticism which "reflects the emergent fake news convictions so evident in supporters of Trumpian populism."[174] Graves and Smith wrote of the impact on Canada of a "new authoritarian, or ordered, populism" that resulted in the 2016 election of President Trump.[174] They said that 34% of Canadians hold a populist viewpoint—most of whom are in Alberta and Saskatchewan—who tend to be "older, less-educated, and working-class", are more likely to embrace "ordered populism", and are "more closely aligned" with conservative political parties.[174] This "ordered populism" includes concepts such as a right-wing authoritarianism, obedience, hostility to outsiders, and strongmen who will take back the country from the "corrupt elite" and return it a better time in history, where there was more law and order.[174] It is "xenophobic", does not trust science, has no sympathy for equality issues related to gender and ethnicity, and is not part of a "healthy" democracy.[174] The authors say that this ordered populism had reached a "critical force" in Canada that is causing polarization and "needs to be addressed".[174]

According to an October 2020 Léger poll for 338Canada of Canadian voters, the number of "pro-Trump conservatives" has been growing in Canada's Conservative Party, which is now under the leadership of Erin O'Toole. Maclean's said that this might explain O'Toole's "True Blue" social conservative campaign.[175] The Conservative Party in Canada also includes "centrist" conservatives as well as Red Tories,[175]—also described as small-c conservative, centre-right or paternalistic conservatives as per the Tory tradition in the United Kingdom. O'Toole featured a modified version of Trump's slogan—"Take Back Canada"—in a video released as part of his official leadership candidacy platform. At the end of the video he called on Canadians to "[j]oin our fight, let's take back Canada."[176] In a September 8, 2020 CBC interview, when asked if his "Canada First" policy was different from Trump's "America First" policy, O'Toole said, "No, it was not."[177] In his August 24, 2019 speech conceding the victory of his successor Erin O'Toole as the newly elected leader of the Conservative Party, Andrew Scheer cautioned Canadians to not believe the "narrative" from mainstream media outlets but to "challenge" and "double check...what they see on TV on the internet" by consulting "smart, independent, objective organizations like the The Post Millennial and True North.[178][169] The Observer said that Jeff Ballingall, who is the founder of the right-wing Ontario Proud,[179] is also the Chief Marketing Officer of The Post Millennial.[180]

Following the 2020 United States elections, National Post columnist and former newspaper "magnate", Conrad Black, who had had a "decades-long" friendship with Trump, and received a presidential pardon in 2019, in his columns, repeated Trump's "unfounded claims of mass voter fraud" suggesting that the election had been stolen.[175][181]

Europe

Trumpism has also been said to be on the rise in Europe. Political parties such as the Finnish Finns Party[182] and France's National Rally[183] have been described as Trumpist in nature. Trump's former advisor Steve Bannon called Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán "Trump before Trump".[184]

See also

- America First policy under the presidency of Donald Trump

- American nationalism in the Donald Trump presidency

- Big lie – Propaganda technique used for political purposes

- Civil rights movement

- Confederate States

- John Birch Society

- The Lincoln Project

- Patriot Party of the United States, the proposed future vehicle of Trumpism in the United States

- Political positions of Donald Trump

- Presidency of Donald Trump

- Reagan Democrat

- Reality distortion field

- Republican Voters Against Trump

- Veracity of statements by Donald Trump

Notes

- The Albert Lea Tribune's description of the scene at the September 13, 2020, "United We Stand & Patriots March for America" was that "[p]eople rallied outside the Minnesota Capitol in St. Paul on Saturday in support of President Trump, and against statewide pandemic policies they say are infringing on personal freedoms and damaging the economy. [...] Some in the crowd carried long guns and wore body armor." There were physical confrontations resulting in the arrest of two counter-protesters.[1]

- Believing the "Stop the Steal" conspiracy theory of electoral fraud, Trumpists acted after being told minutes prior by Trump to "fight like hell" to "take back our country",[4][5] with his personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani calling for "trial by combat"[6] and son Trump Jr. in the prior week warning "we are coming for you" and calling for "total war" over election results.[7][8]

- Multiple academics have made the same comparison, with Yale's Jason Stanley going furthest, observing that while Trump is not a fascist, "I think you could legitimately call Trumpism a fascist social and political movement" and that "he's using fascist political tactics. I think there's no question about that. He is calling for national restoration in the face of humiliations brought on by immigrants, liberals, liberal minorities, and leftists. He's certainly playing the fascist playbook."[31] Philosopher Cornel West agrees that Trump has fascist proclivities and claims his popularity signals that neo-fascism is displacing neoliberalism in the United States.[32] Harvard historian Charles Clavey thinks that the authors of the Frankfurt School studying the sudden victory of fascism in Germany offer the best insights into Trumpism. These similarities include the rhetoric of self-aggrandizement, victimhood, accusation and his solicitation of unconditional support for his leadership which alone can return the country from the moral and political decay it has fallen into.[28]

- David Livingstone Smith, a scholar of history, psychology and anthropology, goes into greater detail on the similarities between Trump and the fascist pattern of persuasion described by Roger Money-Kyrle, who witnessed fascist rallies in 1930s Germany. The psychological linkage between the leader and supporters in mass rallies, the melancholia-paranoia-megalomania pattern, recitation of shared domestic dreads, promotion of fear mongering conspiracy theories painting out-groups as the cause of the problems, simplified solutions presented in absolute terms and the promotion of a singular leader capable of returning the country to its former greatness.[35]

- For an elaboration of the fascist idea and political force of leader viewed as an anointed one, or a messiah, see:

- Waite, Robert G. L (1993) [1977]. The Psychopathic God. New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 31–32, 343. ISBN 0-306-80514-6.

- Elaina Plott covers the Republican Party and conservatism as a national political reporter for The New York Times. In her in-depth article on how Trump has remade the Republican Party, Plott interviewed thirty or so Republican officials.

- In contrast, the Democratic Party "adopted a 91-page document with headings such as 'Healing the Soul of America' and 'Restoring and Strengthening Our Democracy'", with disputes over the lack of "language endorsing universal healthcare or the 'Green New Deal' environmental plan."

- Trump's scenic construction (introduction of characters and setting stage depicting an issue) use black and white terms like "totally", "absolutely, "every", "complete", "forever" to describe malevolent forces, or the coming victory. John Kerry is a "total disaster" and Obamacare will "destroy American health care forever". Kenneth Burke referred to this "all or none" staging as characteristic of "burlesque" rhetoric.[78] Instead of a world involving a variety of complex situations requiring nuanced solutions acceptable to a multiplicity of interested groups, for the agitator the world is a simple stage populated by two irreconcilable groups and dramatic action involves decisions with simple either-or choices. Because all players and issues are painted using black and white terms, there is no possibility of working out a common solution.[79]

- The academic peer-reviewed journal Social Psychological and Personality Science published the article "Group-Based Dominance and Authoritarian Aggression Predict Support for Donald Trump in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election", describing a similar study with the same conclusion.[111]

- One Yale/NSF-funded study asked participants to evaluate data on a skin-cream product's efficacy. People with good math skills could interpret the data correctly but once politics was introduced, with data demonstrating whether gun control decreased or increased crime, the same participants, whether liberal or conservative, who were good at math, misinterpreted the results to conform to their political leanings. This study disconfirms the "science comprehension thesis" and supports the "identity-protective cognition thesis" explanations for inability to agree on shared facts having to do with politicized public policy.[138]

References

- Hovland 2020.

- Bebout 2021.

- Bidgood & Ulloa 2020.

- Guardian01 2021.

- Andersen 2021.

- Blake 2021.

- Haberman 2021.

- da Silva 2020.

- Katzenstein 2019.

- Reicher & Haslam 2016.

- Dean & Altemeyer 2020, p. 11.

- Lowndes 2019.

- Bennhold 2020.

- Lebow 2019.

- Continetti 2020.

- de la Torre et al. 2019, p. 6.

- Brewster 2020.

- de la Torre et al. 2019, pp. 6, 37, 50, 102, 206.

- Fuchs 2018, pp. 83–84.

- Kuhn 2017.

- Serwer 2017.

- Brazile 2020.

- Glasser 2018.

- Morris 2019, p. 20.

- Lyall 2021.

- Greenberg 2016.

- Morris 2019, p. 21.

- Clavey 2020.

- Lemann 2020.

- Peters 2020.

- Matthews 2020.

- West 2016.

- Goldberg 2020.

- Will 2020.

- Smith 2020, pp. 119–121.

- Horton 2020.

- Fea 2018, p. 108, (epub edition).

- Hedges 2020.

- Jaeger 1985, p. 54.

- Jaeger 1985, p. 58.

- Jaeger 1985, p. 84.

- Fea 2018, pp. 105–112, 148, (epub edition).

- Galli 2019.

- Jeffress & Fea 2016, audio location 10:48.

- Mullen 2018.

- Jeffress & Wehner 2016, audio location=8:20.

- Jeffress 2011, pp. 18, 29, 30–31.

- Henderson 2017.

- Moore 2017.

- Shellnutt 2017.

- Blair 2020.

- Jeffress & Fea 2016, audio location 8:50.

- Shabad et al. 2020.

- Boyd 2005, pp. 9, 34, 87–88, (epub edition).

- Fea 2018, pp. 147, 165–170, (epub edition).

- Green 2021.

- Rudolf 2017.

- Assheuer 2018.

- Smith & Townsend 2018.

- Tharoor 2018.

- Diamond 2016.

- Kuhn 2018.

- Zengerle 2019.

- Wintour 2020.

- Harwood 2017.

- Partington 2018.

- Thompson 2017.

- Plott 2020.

- Zurcher 2020.

- Hochschild 2016, p. 8,14,223.

- Thompson 2020.

- NYTimes1 2016.

- Hochschild 2016, p. 230,234.

- Hochschild 2016, p. 223.

- Marietta et al. 2017, p. 330.

- Tarnoff 2016.

- Marietta et al. 2017, pp. 313, 317.

- Appel 2018, pp. 162–163.

- Löwenthal & Guterman 1970, pp. 92–95.

- Löwenthal & Guterman 1970, p. 93.

- Smith 2020, p. 121.

- Money-Kyrle 2015, pp. 166–168.

- Pulido et al. 2019.

- Hall, Goldstein & Ingram 2016.

- Schneiker 2018.

- Connolly 2017, p. 7.

- Neuborne 2019, p. 32.

- Rosenfeld 2019.

- Neuborne 2019, p. 34.

- Neuborne 2019, p. 36.

- Neuborne 2019, p. 39.

- Neuborne 2019, p. 37.

- Connolly 2017, p. 11.

- Guilford 2016.

- Sexton 2017, pp. 104–108.

- Nessen 2016.

- Newkirk 2016.

- Connolly 2017, p. 13.

- Le Bon 2002, pp. xiii, 8, 91–92.

- Zaretsky 2016.

- Reicher 2017, pp. 2–4.

- Connolly 2017, p. 15.

- Kessler & Kelly 2018.

- Kessler, Rizzo & Kelly 2020, pp. 16, 24, 46, 47, (ebook edition).

- Pfiffner 2020, pp. 17–40.

- Connolly 2017, pp. 18–19.

- Rutenberg, Jim; Becker, Jo; Lipton, Eric; Haberman, Maggie; Martin, Jonathan; Rosenberg, Matthew; Schmidt, Michael S. (January 31, 2021). "77 Days: Trump's Campaign to Subvert the Election - Hours after the United States voted, the president declared the election a fraud — a lie that unleashed a movement that would shatter democratic norms and upend the peaceful transfer of power". The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- Rosenberg, Matthew; Rutenberg, Jim (February 1, 2021). "Key Takeaways From Trump's Effort to Overturn the Election - A Times examination of the 77 days between election and inauguration shows how a lie the former president had been grooming for years overwhelmed the Republican Party and stoked the assault on the Capitol". The New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- Stenner & Haidt 2018, p. 136.

- Pettigrew 2017, p. 107.

- Womick et al. 2018.

- Dean & Altemeyer 2020, p. 140.

- Dean & Altemeyer 2020, p. 154.

- Dean & Altemeyer 2020, p. 188.

- Dean & Altemeyer 2020, p. 218.

- Dean & Altemeyer 2020, p. 258.

- Dean & Altemeyer 2020, p. 227.

- Pettigrew 2017, pp. 5–6.

- Pettigrew 2017, p. 108.

- Feldman 2020.

- Pettigrew 2017, pp. 112–113.

- Burnand 1892.

- Stoller 2017, p. 58.

- Blair 2000, p. 275, (epub edition).

- Mansfield 2017, p. 77.

- Kruse 2017.

- Lifton 2019, pp. 131-132.

- Parker 2020.

- Lifton 2019, p. 11, epub edition).

- Golec de Zavala et al. 2009, pp. 6, 43–44.

- Hogg, van Knippenberg & Rast 2012, p. 258.

- Federico & Golec de Zavala 2018, p. 1.

- Lifton 2019, p. 129.

- Lifton 2019, p. 128.

- Brooks 2020.

- Imhoff & Lamberty 2018, p. 4.

- McIntyre 2018, p. 94.

- Kahan et al. 2017.

- McIntyre 2018, p. 97.

- Paravati et al. 2019.

- Imhoff & Lamberty 2018, p. 6.

- van Prooijen 2018, p. 65.

- Bote 2020.

- Bump 2020.

- Suessenbach & Moore 2020, abstract.

- Denby 2015.

- Bader 2016.

- Trump 2019.

- Trump & Schwartz 2011, p. 49, (epub edition).

- Hart 2020, p. 4.

- Matthews, Dylan (January 14, 2021). "The F Word". Vox. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Boucheron, Patrick (February 8, 2020). "'Real power is fear': what Machiavelli tells us about Trump in 2020". The Guardian. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Robertson, Derek (May 16, 2020). "What Liberals Don't Get About Trump Supporters and Pop Culture". Politico. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- "Is This Trump's Reichstag Fire Moment?". The Intercept. June 4, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- https://journals.openedition.org/tp/820

- Shenk, Timothy (August 16, 2016). "The dark history of Donald Trump's rightwing revolt". The Guardian. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Iling, Sean (November 16, 2018). "What Machiavelli can teach us about Trump and the decline of liberal democracy". Vox. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- Finn 2017.

- https://www.newsweek.com/robert-paxton-trump-fascist-1560652

- Matthews 2015.

- Finchelstein 2017, pp. 11–13.

- Browning 2018.

- Seeßlen 2017.

- CollinsDictionary 2016.

- Temelkuran 2019.

- Hopkin & Blyth 2020.

- Delacourt 2020.

- Donolo 2021.

- Fawcett 2021.

- Donolo 2020.

- Global 2021.

- Fournier 2021.

- The Current 2020.

- Graves 2020.

- Fournier 2020.

- Woods 2020.

- CBC 2020.

- CBC1 2020.

- NaPo 2018.

- Samphire 2019.

- Fisher 2019.

- Helsinki Times, April 13, 2019.

- Schneider 2017.

- Kakissis 2019.

Bibliography

Books

- Blair, Gwenda (2000). The Trumps: Three Generations of Builders and a Presidential Candidate. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80849-8.

- Boyd, Gregory (2005). The Myth of a Christian Nation: How the Quest for Political Power Is Destroying the Church. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan. ISBN 0-3102-8124-5.

- Burnand, Francis Cowley, ed. (2004) [1892]. Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 102, April 23, 1892. Project Gutenberg.

- Connolly, William (2017). Aspirational Fascism: The Struggle for Multifaceted Democracy under Trumpism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1517905125.

- Dean, John; Altemeyer, Robert A. (2020). "Chapter 10: National Survey on Authoritarianism". Authoritarian Nightmare: Trump and his Followers (e-book ed.). Brooklyn, NY: Melville House Publishing. ISBN 978-1612199061.

- de la Torre, Carlos; Barr, Robert R.; Arato, Andrew; Cohen, Jean L.; Ruzza, Carlo (2019). Routledge Handbook of Global Populism. Routledge International Handbooks. London/New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-22644-6.

- Frum, David (2018). Trumpocracy. New York: Harper. p. 336. ISBN 978-0062796745.

- Dionne, E. J.; Mann, Thomas E.; Ornstein, Norman (2017). One Nation After Trump: A Guide for the Perplexed, the Disillusioned, the Desperate, and the Not-yet Deported. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-1250293633.

- Fea, John (2018). Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump. Grand Rapids, Mchigan: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-1-4674-5046-1.

- Feldman, Stanley (2020). "Authoritarianism, threat, and intolerance". In Borgida; Federico; Miller (eds.). At the Forefront of Political Psychology: Essays in Honor of John L. Sullivan. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1000768275.

- Fuchs, Christian (2018). Digital Demagogue: Authoritarian Capitalism in the Age of Trump and Twitter. Pluto Press. JSTOR j.ctt21215dw.8.

- Hart, Roderick P. (2020). "Trump's Arrival". Trump and Us (What He Says and Why People Listen). Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–22. doi:10.1017/9781108854979.001. ISBN 9781108854979.

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell (2016). Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (e-book ed.). New York, NY: The New Press. ISBN 978-1-62097-226-7.

- Jaeger, C. Stephen (1985). The Origins of Courtliness: Civilizing Trends and the Formation of Courtly Ideals. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ASIN B008UYP8H8.

- Jeffress, Robert (2011). Twilight's Last Gleaming: How America's Last Days Can Be Your Best Days. Brentwood, TN: Worthy Publishing. ISBN 978-1936034581.

- Kellner, Douglas (2020). "Donald Trump and the Politics of Lying". In Peters, Michael A.; Rider, Sharon; Hyvonen, Mats; Besley, Tina (eds.). Post-Truth, Fake News: Viral Modernity & Higher Education (PDF). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-8013-5. ISBN 978-981-10-8013-5.

- Kessler, Glenn; Rizzo, Salvador; Kelly, Meg (2020). Donald Trump and His Assault on Truth: The Presidents Falsehoods, Misleading Claims and Flat-Out Lie. Washington Post Books. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-9821-5108-9.

- Le Bon, Gustave (2002) [1st pub. 1895]. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486419565.

- Lifton, Robert Jay (2019). Losing Reality: On Cults, Cultism, and the Mindset of Political and Religious Zealotry (ePub) ed.). New York/London: New Press. ISBN 978-1620975121. (Page numbers correspond to the ePub edition.)

- Löwenthal, Leo; Guterman, Norbert (1970) [1949]. Prophets of Deceit: A Study of the Techniques of the American Agitator (PDF). New York: Harper & Brothers. ISBN 978-0870151828. (Cited page numbers correspond to the online version of the 1949, at AJArchives.org.)

- Mansfield, Stephen (2017). Choosing Donald Trump God, Anger, Hope, and Why Christian Conservatives Supported Him. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-4934-1225-9.

- McIntyre, Lee (2018). Post-Truth. MIT Press Essential Knowledge Series. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262535045.

- Money-Kyrle, Roger (2015) [1941]. "The Psychology of Propaganda". In Meltzer, Donald; O'Shaughnessy, Edna (eds.). The Collected Papers of Roger Money-Kyrle. Clunie Press.

Money-Kyle describes not a rhetorical pattern of problem–conflict–resolution, but a progression of psychoanalytic states of mind in the three steps: 1) melancholia, 2) paranoia and 3) megalomania.

- Nash, George H. (2017). "American Conservatism and the Problem of Populism". In Kimball, Roger (ed.). Vox Populi: The Perils and Promises of Populism. New York: Encounter Books. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-59403-958-4.

- Neuborne, Burt (2019). When at Times the Mob Is Swayed: A Citizen's Guide to Defending Our Republic (ePub) ed.). New York/London: The New Press. ISBN 978-1620973585.(Page numbers correspond to the ePub edition.)

- Pfiffner, James (2020). "The Lies of Donald Trump: A Taxonomy". Presidential Leadership and the Trump Presidency (PDF). Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 17–40. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-18979-2_2. ISBN 978-3-030-18979-2. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Sexton, Jared Yates (2017). The People Are Going to Rise Like the Waters Upon Your Shore: A Story of American Rage. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press. ISBN 978-1-61902-956-9.

- Smith, David Livingstone (2020). On Inhumanity: Dehumanization and How to Resist It (ePub ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190923020.

- Stenner, Karen; Haidt, Jonathan (2018). "Authoritarianism is not a momentary madness, but an eternal dynamic within liberal democracies". In Sunstein, C. R. (ed.). Can It Happen Here? Authoritarianism in America. New York: Dey Street Books. ISBN 978-0062696212.

- Temelkuran, Ece (2019). How to Lose a Country: The 7 Steps from Democracy to Dictatorship. ISBN 978-0008340612.

- Trump, Donald J.; Schwartz, Tony (2011) [1987]. Trump: The Art of the Deal. Random House- Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-307-57533-3.

- van Prooijen, Jan-Willem (2018). The Psychology of Conspiracy. The Psychology of Everything. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-52541-9.

- Woodward, Bob (2018). Fear: Trump in the White House. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-4711-8130-6.

Articles

- Appel, Edward C. (2018). "Burlesque, Tragedy, and a (Potentially) "Yuuuge" "Breaking of a Frame": Donald Trump's Rhetoric as "Early Warning"?". Communication Quarterly. 66 (2): 157–175. doi:10.1080/01463373.2018.1439515. S2CID 149031634.

- Assheuer, Thomas (May 16, 2018). "Donald Trump: Das Recht bin ich". Die Zeit (in German).

- Bader, Michael (December 25, 2016). "The Decline of Empathy and the Appeal of Right-Wing Politics – Child psychology can teach us about the current GOP". Psychology Today. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- Bebout, Lee (January 7, 2021). "Trump tapped into white victimhood – leaving fertile ground for white supremacists". The Conversation. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

Trumpism tapped into a long-standing sense of aggrievement that often – but not exclusively – manifests as white victimhood.

- Bennhold, Katrin (September 7, 2020). "Trump Emerges as Inspiration for Germany's Far Right". The New York Times.

- Bidgood, Jess; Ulloa, Jazmine (October 1, 2020). "A debate and a rally show Trump's closing strategy: Tapping into the white grievance of his political bubble". The Boston Globe. Duluth, Minneapolis. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- Blair, Leonardo (December 15, 2020). "Beth Moore draws flak and praise after warning Christians against 'dangerous' Trumpism". Christian Post. Retrieved December 28, 2020.

- Blake, Aaron (January 7, 2021). "'Let's have trial by combat': How Trump and allies egged on the violent scenes Wednesday". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- Blyth, Mark (November 15, 2016). "Global Trumpism: Why Trump's Victory was 30 Years in the Making and Why It Won't Stop Here". Foreign Affairs.

- Andersen, Travis (January 6, 2021). "Before mob stormed US Capitol, Trump told them to 'fight like hell' –". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- Bote, Joshua (October 22, 2020). "Half of Trump supporters believe in QAnon conspiracy theory's baseless claims, poll finds". USA Today. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Brazile, Donna (August 28, 2020). "Convention shows Republican Party has died and been replaced by Trump Party". Fox News.

- Brewster, Jack (November 22, 2020). "Republicans Ask, Whether Or Not Trump Runs In 2024, What Will Come Of Trumpism?". Forbes. Retrieved November 22, 2020.

- Brooks, David (November 30, 2020). "David Brooks column: The rotting of the Republican mind". New York Times.

- Browning, Christopher R. (October 25, 2018). "The Suffocation of Democracy". The New York Review. 65 (16).

Trump is not Hitler and Trumpism is not Nazism, but regardless of how the Trump presidency concludes, this is a story unlikely to have a happy ending.

- Bump, Philip (October 20, 2020). "Even if they haven't heard of QAnon, most Trump voters believe its wild allegations". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2020.

- Erin O'Toole (newly-elected leader of the CPC) (September 8, 2020). O'Toole on his 'Canada First' policy. Power & Politics. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- "Andrew Scheer praises Erin O'Toole as next leader of Conservative Party". CBC. August 24, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Choma, Becky L.; Hanoch, Yaniv (February 2017). "Cognitive ability and authoritarianism: Understanding support for Trump and Clinton". Personality and Individual Differences. 106 (1): 287–291. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.054. hdl:10026.1/8451.

- Clavey, Charles H. (October 20, 2020). "Donald Trump, Our Prophet of Deceit". Boston Review. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- "Etymology Corner – Collins Word of the Year 2016". Collins Dictionary (online ed.). November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- Continetti, Matthew (December 22, 2020). "Is Trump Really All That Holds the G.O.P. Together?". The New York Times. Retrieved January 4, 2021.

- Cornelis, Ilse; Van Hiel, Alain (2015). "Extreme right-wing voting in Western Europe: The role of social-cultural and antiegalitarian attitudes". Political Psychology. 35 (6): 749–760. doi:10.1111/pops.12187.

- da Silva, Chantal (November 6, 2020). "'Reckless' and 'stupid': Trump Jr calls for 'total war' over election results". The Independent. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Delacourt, Susan (November 8, 2020). "Donald Trump lost, but Trumpism is still thriving. Could it take hold in Canada, too?". Toronto Star. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Denby, David (December 15, 2015). "The Plot Against America: Donald Trump's Rhetoric". New Yorker. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- Diamond, Jeremy (July 29, 2016). "Timeline: Donald Trump's praise for Vladimir Putin". CNN.com.

- Donolo, Peter (August 21, 2020). "Trumpism won't happen in Canada – but not because of our politics". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Donolo, Peter (January 9, 2021). "What will become of Trump's Canadian fan base?". Toronto Star. Toronto, Ontario. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Fawcett, Max (January 12, 2021). "Rigged Canadian election? Why Canada's Conservatives can't seem to quit Donald Trump". National Observer. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Federico, Christopher M.; Golec de Zavala, Agnieszka (March 6, 2018). "Collective Narcissism and the 2016 US Presidential Vote" (PDF). Public Opinion Quarterly. Oxford University Press. 82 (1): 110–121. doi:10.1093/poq/nfx048.

- Feldman, Stanley; Stenner, Karen (June 28, 2008). "Perceived threat and authoritarianism". Political Psychology. 18 (4): 741–770. doi:10.1111/0162-895X.00077.

- Finchelstein, Federico (2017). From Fascism to Populism in History. University of California Press. pp. 11–13. ISBN 978-0-520-96804-2.

- Finn, Ed (May 13, 2017). "Is Trump a fascist?". The Indepdenent. Newfoundland.

- Fisher, Marc (May 16, 2019). "After a two-decade friendship and waves of lavish praise, Trump pardons newspaper magnate Conrad Black". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 12, 2021.

- Fournier, Philippe J. (October 1, 2020). "How much do Canadians dislike Donald Trump? A lot". Maclean's. Retrieved January 12, 2021.