President of the Czech Republic

The President of the Czech Republic is the elected formal head of state of the Czech Republic and the commander-in-chief of the military of the Czech Republic.[2]

| President of the Czech Republic

Prezident České republiky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Style | His Excellency |

| Residence | Prague Castle |

| Seat | Prague, Czech Republic |

| Appointer | Popular vote |

| Term length | Five years Renewable once, consecutively |

| Precursor | President of Czechoslovakia 14 November 1918 |

| Inaugural holder | Václav Havel 2 February 1993 |

| Formation | Constitution of the Czech Republic |

| Salary | 2,235,600 Kč ($ 86,830) [1] |

| Website | www.hrad.cz |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Czech Republic |

|

|

The president does not have nearly as much power as counterparts in the United States and president of France, as the Czech Republic is a parliamentary republic. However, unlike counterparts in other Central European countries such as Austria and Hungary, who are generally considered figureheads, the Czech president has a considerable role in political affairs. Because many powers can only be exercised with the signatures of both the President and the Prime Minister of the Czech Republic, responsibility over some political issues is effectively shared between the two offices.

The current president, Miloš Zeman, assumed the office on 8 March 2013. His term will end on 8 March 2023.

Powers

The framers of the Constitution of the Czech Republic intended to set up a parliamentary system, with the Prime Minister as the country's leading political figure and de facto chief executive and the president as a ceremonial head of state. However, the stature of the first president, Václav Havel, was such that the office acquired greater influence than the framers intended, although not nearly as powerful as the Czechoslovak presidency.[3]

Absolute authority

The President of the Czech Republic has the authority to act independently in a number of substantive areas. One of the office's strongest powers is that of veto, which returns a bill to parliament. Although the veto may be overridden by parliament with an absolute majority vote (over 50%) of all deputies,[4] the ability to refuse to sign legislation acts as a check on the power of the legislature. The only kind of bills a President can neither veto nor approve are acts that would change the constitution.[5]

The president also has the leading role in the appointment of persons to key high offices, including appointment of judges to the Supreme and Constitutional Courts (with the permission of the Senate), and members of the Bank Board of the Czech National Bank.[5]

Limited sole authority

There are some powers reserved to the President, but can be exercised only under limited circumstances. Chief among these is the dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies. While the president can dissolve the Chamber on his own authority,[5] forcing a new election of that body within 60 days,[6] this can be done only under conditions prescribed by the constitution.[7]

Duties shared

Many of the President's powers can only be exercised with the assent of the Government, as expressed by the signature of the Prime Minister. These include all matters having to do with foreign relations and the use of the military, the appointment of judges to lower courts, and the granting of amnesty. Except when the Chamber of Deputies has been dissolved because of its failure to form or maintain a government,[7] the President may call for elections to the Chamber and the Senate only with the Prime Minister's approval.[8]

The President also shares responsibility with the Chamber of Deputies for appointing the president and vice president of the Supreme Control Office[9] – the body in charge of implementing the national budget – although this appointment does not technically require the signature of the Prime Minister.[5]

Immunity from prosecution

Under Art. 54 (3) and 65 (3) of the constitution, the President may not be held liable for any alleged criminal acts while executing the duties of office. Such prosecution may not occur either while the president is in office or at any time thereafter. Furthermore, Art 65 (1) prevents trial or detention for prosecution of a criminal offense or tort while in office. The only sort of prosecution allowed for a sitting President is that of high treason, which can only be carried out by the Senate, and can only result in removal from office and a ban on regaining the office at a later date.[10]

Ceremonial powers

Many of the duties of the Czech President can be said to be ceremonial to one degree or another, especially since the President has relatively few powers independent of the will of the Prime Minister. A good example of this is the status as commander in chief of the military. No part of these duties can take place but through the assent of the Prime Minister. In matters of war, he is in every sense merely a figurehead, since the constitution gives all substantive constitutional authority over the use of the armed forces to the parliament.[11][12] In fact, the only specific thing the constitution allows the president to do with respect to the military is to appoint its generals – but even this must be done with the signature of the Prime Minister.[8]

Many of the President's ceremonial duties fall under provisions of the constitution that allow the exercise of powers "not explicitly defined" in the constitution, but allowed by a lesser law.[8] In other words, Parliament has the power to allow the President whatever responsibilities they deem proper, without necessarily having to amend the constitution. Such a law was passed in 1994 with respect to the awarding of state decorations. While the constitution explicitly allows the conferring of honors and awarding of medals by the president only with the signature of the Prime Minister, parliament acted in 1994 to grant the president power to do so on his own authority. Hence, this particular duty is effectively shared between the parliament and the president.[13] The act even allows the president to choose someone to perform the actual presentation ceremony.

Election

Until 1956, the office of president was filled following an indirect election by the Parliament of the Czech Republic. In February 2012, a change to a direct election was passed by the Senate,[14] and after the related implementation law also was passed by both chambers of the parliament, it was enacted by presidential assent on 1 August 2012;[15] meaning that it legally entered into force on 1 October 2012.

Electoral procedure

The term of office of the President is 5 years.[16] A newly elected president will begin the five-year term on the day of taking the official oath.[17] Candidates standing for office must be 40 years of age, and must not have already been elected twice consecutively.[18] Since the only term limit is that no person can be elected more than twice consecutively, a person may theoretically achieve the presidency more than twice. Prospective candidates must either submit petitions with the signatures of 50,000 citizens, or be nominated by 20 deputies or 10 senators.

The constitution does not prescribe a specific date for presidential elections, but stipulates that elections shall occur in the window between 30 and 60 days before the end of the sitting president's term, provided that it was called at least 90 days prior to the selected election day.[19] In the event of a president's death, resignation or removal, the election can be held at the earliest 10 days after being called and at the latest 80 days after vacancy of the presidential seat.[17] If no candidate receives a majority, a runoff is held between the top two candidates.

The constitution makes specific allowances for the failure of a new president to be elected. If a new president has not been elected by the end of a president's term, or if 30 days elapse following a vacancy, some powers are conferred upon the Prime Minister, some are moved to the chairman of the Chamber of Deputies or to the chairman of the Senate, if parliament is in a state of dissolution at the time of the vacancy.[20]

The first direct presidential election in the Czech Republic was held 11–12 January 2013, with a runoff on 25–26 January.

Previous electoral procedure (until 1 October 2012)

Under Article 58 of the current Czech Constitution, nominees to the office must be put forward by no fewer than 10 Deputies or 10 Senators. Once nominees are in place, a ballot can begin. Each ballot can have at most three rounds. In the first round, a victorious candidate requires an absolute majority in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Given a 200-seat Chamber and an 81-seat Senate, a successful first-round candidate requires 101 deputies and 41 senators.[21]

If no single candidate gets a majority of both the Chamber and the Senate, a second round is then called for. At this stage, a candidate requires an absolute majority of merely those actually present at the time of voting in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. The actual number of votes required in the second round might be the same as in the first round, but as in 2008, it can be a little less, due to the absence of a few parliamentarians. Nevertheless, in this second round, a single candidate would need to win a majority in both the Chamber and the Senate.

Should no single candidate achieve a majority of both houses then present, a third round is necessitated. In this final round, which can happen within 14 days of the first round, an absolute majority of deputies and senators present suffices.[22] At this stage, the individual houses of parliament are not considered separately. Assuming that all members of parliament are present, all that is required to win is 141 votes, regardless of the house of origin. If no candidate wins in the third round, another ballot has to be considered in a subsequent joint session of parliament.[23] The process continues under the same rules until a candidate prevails.

In 1993, the Republic's first president, Václav Havel, had little difficulty achieving victory on the first round of the first ballot, but his re-election bid proved bumpier. In 1998, he was elected with a cumulative seven-vote margin on the second round of the first ballot.[24] By contrast, his successor, Václav Klaus, has required the full measure of the process. He narrowly won election on the third ballot at the 2003 election and on the sixth (second attempt, third ballot) in 2008. Both his elections were won in the third round. His biggest margin of victory was two votes.

Dissatisfaction with previous procedure

Following the 2003 and 2008 elections, which both required multiple ballots, some in the Czech political community expressed dissatisfaction with this method of election. In 2008, Martin Bursík, leader of the Czech Green Party, said of the 2008 vote, "We are sitting here in front of the public somewhat muddied by backstage horse-trading, poorly concealed meetings with lobbyists and intrigue."[25] There were calls to adopt a system with a direct election, in which the public would be involved in the voting. However, opponents of this plan pointed out that the presidency had always been determined by indirect vote, going back through several predecessor states to the presidency of Tomáš Masaryk. Charles University political scientist Zdeněk Zbořil suggested that direct voting could result in a president and prime minister who were hostile to each other's goals, leading to deadlock. A system of direct elections was supported by figures including Jiří Čunek (Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People's Party) and Jiří Paroubek (Czech Social Democratic Party), whereas the ruling Civic Democratic Party, under both President Václav Klaus and Prime Minister Mirek Topolánek, was more skeptical. Topolánek commented that it was an advantage that "our presidential elections are not preceded by some campaign, that is unavoidable in a direct election and causes rifts among citizens". Using Poland as an unfavourable example, he said that "when someone talks about how our method of selecting the head of state is undignified, he should first weigh the consequences of a direct vote".[26]

Removal from office

Aside from death, there are only three things that can effect a president's removal from office:

- A President can resign by notifying the President of the Senate.[27]

- The President may be deemed unable to execute his duties for "serious reasons" by a joint resolution of the Senate and the Chamber[20] – although the president may appeal to the Constitutional Court to have this resolution overturned.[28]

- The President may be impeached by the Senate for high treason and convicted by the Constitutional Court.[28]

Trappings of office

Presidential fanfare

Since the first Czechoslovak president Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, the presidential fanfare has been the introduction to Bedřich Smetana's opera Libuše, which is symbol of the patriotism of the Czech people during the Czech National Revival under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

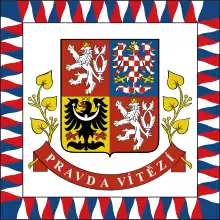

Heraldry

The office of president carries with it an iconography, established through laws passed by the parliament. Perhaps the most visible of these is the flag of the president, as seen at top right. His official motto is the same as that of the Republic: "Pravda vítězí" ("Truth prevails").

Inasmuch as the president is the titular sole administrator of Prague Castle, the presidency may also be said to control the heraldry of that institution as well, including but not limited to the special designs worn by the Castle Guard, which is a special unit of the armed forces of the Czech Republic, organized under the Military Office of the President of the Czech Republic, directly subordinate to the president.

Furthermore, the president, while in office, is entitled to wear the effects of the highest class of the Republic's two ceremonial orders, the Order of the White Lion and the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. By the power of being inaugurated, the President becomes the holder of the highest class of both orders for the duration of his term in office as well as their supreme administrator. By convention, the Parliament allows a retiring President to remain a life-long member of both institutions, with the order decorations returning to the State upon the former President's death.[29][30]

Residences

The official residence of the president of the Czech Republic is Prague Castle. However, the living quarters are small and not particularly comfortable, so recent presidents (Václav Havel and Václav Klaus) have chosen to live elsewhere. The last president to reside more or less full-time in the residence in the Prague Castle was Gustáv Husák. The president also maintains a summer residence at the castle in the village of Lány, 35 km west of Prague.

Living former Presidents

There is one living former Czech President:

_(cropped).JPG.webp)

Václav Klaus

(2003–2013)

June 19, 1941

List of presidents of the Czech Republic

See also

References

- "Prezident Klaus má nárok na 50tisícovou rentu i státní důchod" (in Czech). Mladá fronta DNES. 17 June 2011.

- William M. Mahoney (2011). The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. ABC-CLIO. p. 7. ISBN 9780313363061.

- Thompson, Wayne C. (2008). The World Today Series: Nordic, Central and Southeastern Europe 2008. Harpers Ferry, West Virginia: Stryker-Post Publications. ISBN 978-1-887985-95-6.

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 50

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 62

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 17

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 35

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 63

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 97

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 65 (2)

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 43

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 39

- "The Act on the State Decorations of the CR". Prague Castle. 2 August 2008. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "Radio Prague – Czech Parliament passes direct presidential elections". Radio.cz. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "Klaus signs enacts implementation law, direct elections to be held in 2013 | CZ Presidential Elections". Czechpresidentialelections.com. 2 August 2012. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 55

- "Presidential Powers | CZ Presidential Elections". Czechpresidentialelections.com. 23 October 2010. Archived from the original on 17 January 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 57

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 56

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 66

- Boruda, Ondřej (6 February 2008)."Presidential Election 2008", The Prague Post.

- "Klaus remains favourite in Czech president's election - analyst". ČeskéNoviny.cz. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 58

- "Vaclav Havel gets a second term as president". Agence France Presse. 22 January 1998. Archived from the original on 13 May 2009.

- Jůn, Dominik (13 February 2008). "No-vote creates election 'fiasco". The Prague Post

- Hulpachová, Markéta (13 February 2008). "The future of the electoral process". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008.

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 61

- Constitution of the Czech Republic, Art. 87

- "Order of the White Lion Statutes". Prague Castle. 23 May 2008. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "Tomas Garrigue Masaryk Order Statutes". Prague Castle. 23 May 2008. Archived from the original on 23 May 2008. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

External links

- The Czech constitution. Articles 54–66 are particularly relevant to the presidency.

- The official site of Prague Castle