Rock art of the Chumash people

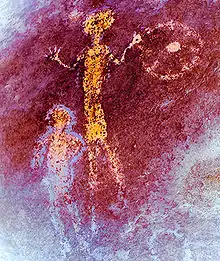

Chumash rock art is a genre of paintings on caves, mountains, cliffs, or other living rock surfaces, created by the Chumash people of southern California. Pictographs and petroglyphs are common through interior California, the rock painting tradition thrived until the 19th century. Chumash rock art is considered to be some of the most elaborate rock art tradition in the region.[1]

The Chumash are probably best known for the pictographs. Which were brightly colored paintings of humans, animals, and abstract circles. They were thought to be part of a religious ritual.

Chumash people

The Chumash lived in the present-day counties of Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Luis Obispo in southern California for 14,000 years. They were a maritime, hunter-gatherer society whose livelihood was based on the sea. They developed excellent skills for catching fish, shellfish, and other marine mammals. Beyond fishing, however, they were also skilled in creating rock art. Hudson and Blackburn define rock art as "an aesthetic, symbolic representation of significant concepts and entities that is painted on or carved into a rock surface." Rock art may have been created by shamans during vision quests, most commonly in the form of pictographs (paintings on rock), but sometimes petroglyphs (engravings on rock) as well. No one is absolutely certain about the meaning of the Chumash Rock art, but scholars generally agree that it is connected with religion and astronomy.

Locations

Chumash rock art is almost invariably found in caves or on cliffs in the mountains, although some small, portable painted rocks have been recorded by Campbell Grant. The rock art sites are always found near streams, springs, or some other source of permanent water. In his research of southern California rock art, Grant recorded numerous sites from different areas that were all close to a water source. He found twelve painted sites in the highest parts of the mountainous Chumash territory, the Ventureño area. The Ventura and Santa Clara Rivers and several coastal streams flow through this area. He also recorded forty-one painted rock art sites in the Cuyama Valley region (north of the Ventureño area), where the Sisquoc River flows between the San Rafael Mountains and the Sierra Madre Mountains. The most easily accessible example is at Painted Cave State Historic Park, which is located in canyons above Santa Barbara.[1]

Painted Rock is a free-standing rock on the Carrizo Plain near the Sierra Madre Mountains at the southern tip of the Great Central Valley.[1] The interior alcove of the horseshoe-shaped rock features pictographs by Chumash, neighboring tribes, and non-Native Americans.

The Burro Flats Painted Cave petroglyphs are located in the Simi Hills in Ventura County. They are on the private land of Rocketdyne's Santa Susana Field Laboratory (SSFL), which has protected them from public harm since 1947. The SSFL is closed and in the initial stage of a significant toxins and radionuclides site investigation and cleanup. Boeing, U.S. DOE, and NASA (current property owners and responsible parties) and the California Department of Toxic Substances Control (DTSC) are responsible to protect Chumash and other historical elements during the extensive SSFL work.[2]

Religious aspects of art

Chumash traditional narratives in oral history say that religious specialists, known as 'alchuklash created the rock art.[1] Non-Chumash people call these practitioners medicine men or shamans.[3] According to David Whitley, shamanism is "a form of worship based on direct, personal interaction between a shaman (or medicine man) and the supernatural (or sacred realm and its spirits)." In Chumash territory, the sites for the vision quests were usually located near the shaman's village. The Chumash considered caves, rocks, and water sources quite powerful, and the shamans saw them as a "portal to the sacred realm...where they could enter the supernatural." The way a shaman interacted with the supernatural was by entering a hallucinogenic trance, or altered state of consciousness. In this altered state, brought on either by surprisingly potent native tobacco or jimsonweed, shamans received visions and supernatural power from spirit helpers often in the forms of dangerous and powerful animals like rattlesnakes and grizzly bears. Spirit helpers almost never took the form of an animal that was an important source of food, because it was 'taboo for a shaman to eat meat from the species of his helper.' The discovery of chewed 'quids' in the ceiling of a site called Pinwheel Cave which have been identified as 'Datura Wrightii' has provided the first confirmation of the consumption of an hallucinogen at any Chumash site (and possibly any in the world) (See 10.1073/pnas.2014529117).[4]

Subject matter and materials

Chumash rock art depicts images like humans, animals, celestial bodies, and other (at times ambiguous) shapes and patterns. These depictions vary considerably and appear to be in no particular order or arrangement. The colors of the paintings vary as well, from red or black monochromes (different shades of a single color) to elaborate polychromes (many various colors). The Chumash made paint from a mixture of mineralized soil, stone mortar, and some kind of liquid binder like blood or oil from animals or mashed seeds. The addition of an oil binder helped to make the paint permanent and waterproof. Orange and red paint contained hematite or iron oxide, while yellow came from limonite, blue and green from copper or serpentine, white from kaolin clays or gypsum, and black from manganese or charcoal. Paint was applied with a person's finger or a brush. Grant organized the types of images depicted in the paintings into two categories: representational and abstract. Representational images include squares, circles and triangles, zigzags, crisscrosses, parallel lines, and pinwheels.,[5] Grant noted that in settled villages, abstract paintings were prominent, while the areas occupied by bands of hunting people reveal representational images.

Interpretations

In the early 20th century, non-Natives began studying California rock art, including a number of archaeologists, such as Julian Steward and Alfred Kroeber. Because of some commonly occurring symbols in paintings, it was believed that at least portions of the rock art depicted themes of fertility, water, and rain; however, the Native California Indians are very reluctant to talk to anyone about the rock art and some deny any knowledge of it altogether. The natives' hesitancy to discuss the art led archaeologists to believe that they had no idea of the origin of the pictographs. Kroeber recorded some of his thoughts on the origins of the rock art in 1925.

"The cave paintings of [Southern California]...represent a particular art, or local style or cult. This can be connected, in all probability, with the technological art of the Chumash. [An] association with...religion is also to be considered, although nothing positive is known in the matter. Many of the pictures may have been made by shamans; and it is quite possible that medicine men were not connected with the making of any."[6]

Kroeber was unsure about what specific associations could be made between the paintings and the artists. Julian Steward researched California rock art as well, and in 1929 he deduced that the only way to understand the meanings of the petroglyphs and pictographs was to compare them with the art and symbolism of the different Indian groups and their respective culture areas. In his book Petroglyphs of California, Steward wrote: "It has frequently been stated that the petroglyphs and pictographs are meaningless figures made in idle moments by some primitive artist. The facts of distribution, however, show that this cannot be true. Since design elements and style are grouped in limited areas, the primitive artist must have made the inscriptions with something in mind. ... He executed, not random drawings, but figures similar to those made in other parts of the same area."[7][8]

At Painted Cave, a circle enclosing five spokes surrounded by other circles–some spoked, some rayed–is thought to represent the solar eclipse of November 24, 1677. Pinwheel shapes, dots, and concentric circles are believed to be celestial bodies. Figures combining human and animal features represent states of transformation the 'alchuklash experienced. Certain animals, such as rattlesnakes and frogs, are believed to represent spirit helpers.[3]

Arborglyph

In 2006, an arborglyph on an oak tree in the Santa Lucia Range in San Luis Obispo County was discovered to be Chumash art. The tree, locally known as the "scorpion tree," was originally believed to have been the work of cowboys. However, archaeologists believe it to be the only known Native American arborglyph in the western United States. The work on the tree is theorized to be correlated to the movement of celestial bodies. If true, it would demonstrate that Chumash art was likely used as astronomical calendars.[9]

Dating

Concerning the age of the paintings, Grant says "a radiocarbon test on pigment from a Santa Barbara area pictograph site showed that the sample was 'not over 2,000 years old.'"[10]

Notes

- Penney 2004, p. 129.

- Guttenberg, Corbett & Knight 2010.

- Penney 2004, p. 130.

- David W. Robinson, Kelly Brown, Moira McMenemy, Lynn Dennany, Matthew J. Baker, Pamela Allan, Caroline Cartwright, Julienne Bernard, Fraser Sturt, Elena Kotoula, Christopher Jazwa, Kristina M. Gill, Patrick Randolph-Quinney, Thomas Ash, Clare Bedford, Devlin Gandy, Matthew Armstrong, James Miles, David Haviland. Datura quids at Pinwheel Cave, California, provide unambiguous confirmation of the ingestion of hallucinogens at a rock art site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Nov 2020, 202014529; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2014529117

- Hunt, Katie (November 23, 2020). "Native Californians got high on hallucinogens and painted rock art, study finds". CNN. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- Grant 1965, p. 80.

- Steward 1929, pp. 224–225.

- Grant 1965, p. 91.

- Saint Onge, Johnson & Talaugon 2009.

- Grant 1965, p. 123.

References

- Grant, Campbell (1965), The Rock Paintings of the Chumash: A Study of the California Indian Culture, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press

- Guttenberg, Richard; Corbett, Ray; Knight, Albert (June 2010), Final Report: Cultural Resource Compliance and Monitoring Results for USEPA's Radiological Study of the Santa Susana Field Laboratory Area IV and Northern Buffer Zone (PDF)

- Penney, David W. (2004), North American Indian Art, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-20377-6

- Steward, Julian Haynes (1929), "Petroglyphs of California and Adjoining States", University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 24 (2): 47–238

- Saint Onge, Rex W.; Johnson, John R.; Talaugon, Joseph R. (2009), "Archaeological Implications of a Northern Chumash Arborglyph", California and Great Basin Anthropology, 29 (1), ISSN 0191-3557

Further reading

- Fagan, Brian (2005), Ancient North America (4 ed.), London: Thames and Hudson

- Hudson, Travis; Blackburn, Thomas C. (1986), The Material Culture of the Chumash Interaction Sphere (4 ed.), Menlo Park, CA: Ballena Press

- Whitley, David S. (1996), A Guide to Rock Art Sites: Southern California and Southern Nevada, Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company

- Whitley, David S. (2000), The Art of the Shaman: Rock Art of California, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press