SS Choctaw

SS Choctaw was an American semi-whaleback freighter that was in service between 1892 and 1915. She was a monitor vessel containing elements of traditional lake freighters and the whaleback ships that were designed by Alexander McDougall. Choctaw was built in 1892 by the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company in Cleveland, Ohio, and was originally owned by the Lake Superior Iron Company. She was sold to the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company in 1894 and spent the rest of her working life with the firm.

SS Choctaw A painting by Great Lakes marine artist Howard Freeman Sprague (1871-1899), showing her in her original livery under the Lake Superior Iron Company (see "S" on funnel) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Choctaw |

| Namesake: | Choctaw people |

| Operator: |

|

| Port of registry: | Ishpeming, Michigan, United States |

| Builder: | Cleveland Shipbuilding Company |

| Yard number: | 17 |

| Launched: | May 25, 1892 |

| In service: | June 24, 1892 |

| Out of service: | July 11, 1915 |

| Identification: | Registry number US 126874 |

| Fate: | Rammed by the Canadian steamer Wahcondah on Lake Huron |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Lake freighter |

| Tonnage: |

|

| Length: | 266.9 ft (81.4 m) |

| Beam: | 38.1 ft (11.6 m) |

| Depth: | 17.9 ft (5.5 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 1 × fixed pitch propeller |

| Capacity: | 2,800 short tons (2,500 t) |

| Crew: | 22 |

CHOCTAW (shipwreck) | |

| |

| Location | Lake Huron, approximately five miles east of Presque Isle Light.[1] |

| Coordinates | 45.53401°N 83.5093°W |

| Built | 1892 |

| Built by | Cleveland Shipbuilding Company |

| Architectural style | Shipwreck site |

| NRHP reference No. | 100003214[2][3] |

| Added to NRHP | December 10, 2018 |

On July 11, 1915, east of Presque Isle Light on Lake Huron while bound for Marquette, Michigan with a cargo of coal from Cleveland, Ohio, due to foggy conditions, Choctaw was rammed by the Canadian canaller Wahcondah and sank.

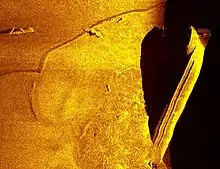

For a long time, shipwreck hunters searched for the wreck of Choctaw due to her unique "straight-back" design. The wreck was located by a team from the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary on May 23, 2017, almost 102 years after she sank. She was discovered resting in about 300 feet (91 m) of water, lying on her starboard side with the bow partially buried in the lake bottom. The wreck was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 10, 2018.

History

Design and construction

'SS Choctaw was named after the Choctaw Indian tribe from the southern United States.[4] She was built in 1892 on the banks of the Cuyahoga River by the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company for the Lake Superior Iron Company of Ishpeming, Michigan.[5][6] She was 266.9 feet (81.4 m) in length with a 38.1-foot (11.6 m) beam,[7] and had a 17.9-foot-deep (5.5 m) hold and water bottom. She had a gross tonnage of 1573.61 tons and a net tonnage of 1256.28 tons.[8][9] The vessel had a cutaway stern and seven cargo hatches, and there were no interior bulkheads between the forward collision bulkhead and the engine bulkhead in her stern. When fully loaded, Choctaw could carry 2,800 short tons (2,500 t), at which time she would draw a 16-foot (4.9 m) draft.[10] She was powered by a 900 hp (670 kW) triple expansion steam engine, steam for which was provided by two coal-fired Scotch marine boilers. Choctaw was one of only three semi-whaleback ships ever built; there was an identical sister ship named Andaste and a "near-sister" ship named Yuma.[6][11][12][13][upper-alpha 1]

Choctaw and Andaste had an unusual design. They were straight-back steel freighters, similar to the iconic whaleback design invented by Captain Alexander McDougall but unlike whalebacks, they had straight sides and a conventional bow.[16] This combination meant from the waterline upward, their sides sloped inward in a "tumble-home" configuration. This hybrid design was known as "semi-whalebacks" and like the true whalebacks, they were vulnerable to getting a wet deck in stormy conditions.[6][17]

Service history

Choctaw was launched May 25, 1892, as hull number #17[18] and entered service on June 24, 1892, with the official number #126874.[8] On April 19, 1893, Choctaw was traveling on Lake St. Clair when the cylinder head blew out and the engine exploded. The explosion killed two crew members and injured another.[9][12] On May 20, 1896, Choctaw collided with the larger steel freighter L.C. Waldo, which tore a 10-foot (3.0 m) hole in Choctaw's starboard side and the ship sank onto a shoal at the Soo Locks .[9] On June 1, 1896, temporary repairs were made to Choctaw in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, before she sailed to Cleveland, Ohio.[9][19][20]

At around midnight on May 26, 1900, Choctaw ran aground near Pointe aux Pins on Lake Erie.[21] On April 26, 1902, Choctaw struck a rock or hit the bottom after being lifted by heavy seas near Marquette, Michigan, and partially sank after reaching the shelter of Marquette Harbor.[12][22]

Choctaw was in Marquette Harbor on November 9, 1913, during that year's Great Lakes Storm when her Captain Charles Fox saw the 545-foot-long (166 m) steel freighter Henry B. Smith leave the shelter of the harbor. This would be the last time Henry B. Smith was seen afloat; she was one of the twelve ships that were lost during the storm.[23]

Final voyage and collision

On July 11, 1915, the weather conditions on Lake Huron were very foggy.[24] Choctaw, under the command of Captain Charles A. Fox, was upbound from Cleveland, Ohio, with a cargo of coal and was bound for Marquette, Michigan.[12][25] At around 5:30 a.m. Wahcondah, which was downbound with a cargo of wheat from Fort William, Ontario to Montreal,[26] sighted Choctaw. Upon sighting the other vessel, the captain of Wahcondah ordered the engines of his ship to be reversed but this did not stop Wahcondah from slicing into the port side of Choctaw between her 1st and 2nd cargo hatch. After the collision, the captain of Wahcondah lost sight of Choctaw. The crew of Wahcondah relocated Choctaw after sighting her tall funnel through the heavy fog. Eventually, Captain Fox ordered Choctaw's lifeboats to be lowered but the vessel sank so quickly some of her crew could not make it to her lifeboats in time and had to jump overboard.[27] The crew of Choctaw reached Wahcondah in their own lifeboats.[28] Although Choctaw sank in only 17 minutes, her entire crew of 22 escaped.[9][12][29] Wahcondah took the crew of Choctaw to Sarnia, Ontario.[30] The approximate location of Choctaw's sinking was given as five–six miles (8.0–9.7 km) east of Presque Isle Light.[1][31] According to Fox:

We did not see the Wahcondah until she was within ten feet [3.0 m] of us. She caught us on the port side and struck beams or else she would have cut us in two. We put off in the lifeboats as quickly as possible after we knew the ship could not float. The Choctaw listed to port and began to go down at the head. Then she righted and began to list to the starboard. As she shifted to starboard her stern rose out of the water and she rolled over, going down bottom side up. We were in the yawl boats about 400 feet [120 m] away when she rolled. It sounded as if a million dishes and hundreds of sticks were being broken as the ship rolled over.[32]

The day after she sank, Captain Nelson Brown of the steamer James H. Reed spotted Choctaw's upper cabins floating off Presque Isle, Michigan, and was able to read the ship's name as he approached them.[33] Nine days after Choctaw sank, 40 feet (12 m) of her cabin and several timbers were discovered one mile (1.6 km) north of Middle Island.[33]

Wreck of Choctaw

Known searches

Choctaw was a very sought-after shipwreck because of her unique "straight back" design. Several unsuccessful attempts to locate the ship were made; several of them resulted in the discovery of one or more other wrecks.[12][34]

Shipwreck hunter Stan Stock conducted an independent search for Choctaw in 2003; he located the wreck of the schooner Kyle Spangler but failed to find Choctaw.[12] Shipwreck hunters from Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary collaborated with Stock in 2008 to map the wreck of Kyle Spangler. In August 2008, they partnered with the University of Rhode Island but rather than finding Choctaw, they located the wreck of the passenger steamer Messenger.[12]

In 2011, a group consisting of expert shipwreck hunters and high school students tried to locate Choctaw. Their search effort was charted in a documentary named "Project Shiphunt". Although they failed to locate Choctaw, they found the wrecks of the steel hulled freighter Etruria ,which sank on the lake after a collision with the steamer Amasa Stone,[35] and the schooner M.F. Merrick, which sank in 1889 after a collision with the steamer Rufus P. Ranney.[34]

Discovery

Between April and July 2017, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary collaborated with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Office of Ocean Exploration and Research to test new equipment including unmanned aircraft systems and autonomous underwater vehicles that were designed to search for missing shipwrecks.[36] On May 23, 2017, researchers from Thunder Bay Marine Sanctuary discovered two shipwrecks in the deep waters of Lake Huron,[37][38] off the coast of Presque Isle, Michigan.[36][39] The researchers carried out several investigations between June and August; these investigations confirmed the identities of the early wooden hulled freighter Ohio and Choctaw.[39][40] Ohio was lost on September 26, 1894, when she collided with the schooner Ironton.[36][41][42] Both wrecks are in a place known as "Shipwreck Alley", which is a 448-square-mile (1,160 km2) area of the Lake Huron shoreline that holds an estimated 200 shipwrecks. The US Federal Government named the area the nation's first National Freshwater Marine Sanctuary in 2000.[43][44]

Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary did not announce their discovery until September 1, 2017, and avocational shipwreck hunters continued to search for Choctaw.[45] On August 13, 2017, independent researcher Dan Fountain found Choctaw using a modified fishfinder. On August 20, he returned to the site with veteran shipwreck hunters Ken Merryman and Jerry Eliason to survey the wreck with Eliason's homemade hi-definition drop video system, positively identifying the wreck as Choctaw.[46]

Choctaw today

The remains of Choctaw rest in about 300 feet (91 m) of cold, fresh water. When the vessel sank, the captain reported she "settled by the head soon after the collision, but shortly before she disappeared she rolled to starboard and capsized, going down bottom side up".[25] The wreck rests on her starboard side, nearly upside down, with the exposed section of her hull rising at an angle from the lake bottom. The upper level of her stern cabins broke away when she sank, leaving only the weather deck level cabins intact. The wreckage of her pilothouse lies beside her hull.[33] The entire bow, including the section between the first and the second hatch where the collision occurred, is completely buried and only the last three of her seven cargo hatches remain exposed.[12] There is a sizeable debris field surrounding her wreck, with most of the visible artifacts located near her stern.[33]

The wreck of Choctaw was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 10, 2018, for its state-level significance in engineering and maritime history.[47][3]

Notes

References

- Wrecksite (2014).

- National Park Service (1) (2018).

- National Park Service (2) (2018).

- Greenwood 1998, p. 8.

- Stonehouse 2006, p. 58.

- Michigan Shipwreck Research Association (2020).

- Devendorf 1996, p. 80.

- Bowling Green State University (2) (2010).

- Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library (2020).

- Lake Marine News (1892), p. 4.

- National Park Service (1) (2018), p. 7.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2) (2017).

- Shipbuilding History (2016).

- Bowling Green State University (1) (2010).

- Bowling Green State University (3) (2010).

- Vanderlinden & Bascom 1994, pp. 25–26.

- Boyer 1968, pp. 59–79.

- Swayze (2001).

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1) (1896).

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (2) (1896).

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1900).

- Government Printing Office (1903).

- Thompson 2004, p. 353.

- Adkins (2017).

- National Park Service (1) (2018), p. 8.

- Toronto Marine Historical Society (1980).

- South Bend News-Times (1915).

- Demers (1915), p. 1.

- Scuba Diver Life (2017).

- The Bridgeport Evening Farmer (1915).

- National Park Service (1) (2018), p. 10.

- National Park Service (1) (2018), p. 8-9.

- National Park Service (1) (2018), p. 12.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2) (2011).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1) (2011).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1) (2017).

- Friends of the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary (2017).

- Ainsworth (2017).

- Karoub (2017).

- Association for Great Lakes Maritime History (2018).

- Tuninson (2017).

- Voice of America (2017).

- The Toronto Sun (2017).

- National Public Radio (2017).

- Fountain (2017).

- Bleck (2017).

- National Park Service (1) (2018), p. 13-21.

Sources

- Adkins, Corey (2017). "Northern Michigan in Focus: Shipwreck Discoveries". Cadillac, Michigan: WWTV. Retrieved December 21, 2018.

- Ainsworth, Amber (2017). "Researchers discover remains of 2 century-old shipwrecks in Lake Huron". Detroit, Michigan: WDIV-TV. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library (2020). "Choctaw (1892, Bulk Freighter)". Alpena, Michigan: Alpena County George N. Fletcher Public Library. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- Association for Great Lakes Maritime History (2018). "2017 Award Program". Madison, Wisconsin: Association for Great Lakes Maritime History. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- Bleck, Christie (2017). "In Lake Huron, Underwater Treasures And A Marine Sanctuary Boost Tourism Industry". Marquette, Michigan: The Mining Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- Bowling Green State University (2010). "Andaste (1)". Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- Bowling Green State University (2) (2010). "Choctaw". Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- Bowling Green State University (3) (2010). "Yuma". Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- Boyer, Dwight (1968). Ghost Ships of the Great Lakes. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 59–79. ISBN 0912514477.

- Demers, L.A. (1915). "Wreck report for the Choctaw and the Wahcondah, 1915" (PDF). Southampton, United Kingdom: PortCities Southampton. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- Devendorf, John F. (1996). Great Lakes Bulk Carriers, 1869 – 1985. Niles, Michigan: J.F. Devendorf. ISBN 9781889043036.

- Fountain, Dan (2017). "Ships that go Bump in the Night: Collisions off Presque Isle by Dan Fountain". Marquette, Michigan: Marquette 365. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Friends of the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary (2017). "Two historic Great Lakes shipwrecks discovered in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary". Alpena, Michigan: Friends of the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- Government Printing Office (1903). "Annual report of the Supervising Inspector-general Steamboat-inspection Service, Year ending June 30, 1903". Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. p. 69. Retrieved May 7, 2020 – via Haithi Trust.

- Greenwood, John Orville (April 1998). The fleets of Cleveland-Cliffs, Detroit and Cleveland Navigation, Traverse City Transportation and the Hawgood family. Freshwater Press. ISBN 978-0-912514-57-4.

The CHOCTAW was named for the Choctaw Indian tribe of the southern United States.

- Karoub, Jeff (2017). "Two century-old shipwrecks discovered in Lake Huron". Detroit, Michigan: The Detroit News. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- "Lake Marine News". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. April 1, 1892. p. 4.

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1) (1896). "Choctaw (Propeller), U126874, sunk by collision, 20 May 1896". Ontario, Canada: Maritime History of the Great Lakes. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (2) (1896). "L.C. Waldo (Propeller), U141421, collision, 20 May 1896". Ontario, Canada: Maritime History of the Great Lakes. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- Maritime History of the Great Lakes (1900). "Choctaw (Propeller), U126874, aground, 26 May 1900". Ontario, Canada: Maritime History of the Great Lakes. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- Michigan Shipwreck Research Association (2020). "Andaste". Holland, Michigan: Michigan Shipwreck Research Association. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1) (2011). "Etruria". Washington D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 11, 2018.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2) (2011). "Project Shiphunt". Washington D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1) (2017). "Finding history: The discovery of two lost shipwrecks in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary". Washington D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2) (2017). "Two Historic Shipwrecks Discovered in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary". Washington D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 21, 2018. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- National Park Service (1) (2018). "CHOCTAW Shipwreck Site National Register of Historic Places Registration Form" (PDF). Washington D.C.: National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 1, 2019. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- National Park Service (2) (2018). "National Resister of Historic Places: Weekly List 20181210". Washington D.C.: National Park Service. Retrieved December 19, 2018.

- National Public Radio (2017). "In Lake Huron, Underwater Treasures And A Marine Sanctuary Boost Tourism Industry". Washington D.C.: National Public Radio. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Scuba Diver Life (2017). "Two Shipwrecks Discovered in Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary". Mountain View, California: Scuba Diver Life. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- Shipbuilding History (2016). "Cleveland Shipbuilding, Cleveland and Lorain OH". Shipbuilding History. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- South Bend News-Times (1915). "Saves Wrecked Crew-Choctaw Goes Down Before Men Can Launch Lifeboats". South Bend, Indiana: South Bend News-Times. Retrieved March 5, 2018 – via Library of Congress.

- Stonehouse, Frederick (2006). Haunted Lake Michigan. Lake Superior Port Cities. ISBN 978-0-942235-72-2.

- Swayze, David D. (2001). "Great Lakes Shipwrecks - C". Port Huron, Michigan: Boatnerd. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- The Bridgeport Evening Farmer (1915). "Steamer Sinks After Collision, Crew Reaches Port". Bridgeport, Connecticut: The Bridgeport Evening Farmer. Retrieved January 12, 2019 – via Library of Congress.

- The Toronto Sun (2017). "Two century-old shipwrecks found in Lake Huron". Toronto, Ontario: The Toronto Sun. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- Thompson, Mark L. (April 13, 2004). Graveyard of the Lakes. Great Lakes Books Series. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 353. ISBN 9780814332269.

- Toronto Marine Historical Society (1980). "Ship of the Month No. 96 Wahcondah". Toronto, Ontario: Toronto Marine Historical Society. Retrieved March 5, 2018.

- Tuninson, John (2017). "Two century-old steamer shipwrecks discovered in Lake Huron". Grand Rapids Michigan: Mlive. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- Vanderlinden, Peter J.; Bascom, John H. (1994) [1979]. Great Lakes Ships We Remember. 1. Cleveland: Freshwater Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 9780912514246.

- Voice of America (2017). "US Researchers Discover Two Century-Old Shipwrecks in Lake Huron". Washington D.C.: Voice of America. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- Wrecksite (2014). "SS Choctaw (+1915)". Affligem, Belgium: Wrecksite. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

Further reading

- Great Lakes Register (1916). Great Lakes Register for the Construction and Classification of Steel and Wooden Vessels. Vol. 18. Cleveland: Great Lakes Register. hdl:2027/mdp.39015057176235.

- Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping (1902). Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping.

- Ratigan, William (1977). Great Lakes Shipwrecks & Survivals. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-7010-4.

- Wright, Richard J. (1969). Freshwater Whales: A History of the American Ship Building Company and Its Predecessors. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873380539.