Secession in Turkey

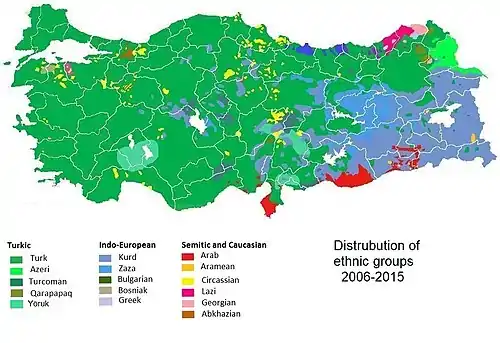

Secession in Turkey is a phenomenon caused by the desire of a number of minorities living in Turkey to secede and form independent national states.[1][2]

Kurdish separatism

At the beginning of the 21st century, the Kurds remain the largest of the groups without their own statehood. The Treaty of Sèvres between Turkey and Triple Entente (1920) provided for the creation of an independent Kurdistan. However, this agreement never entered into force and was cancelled after the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). In the 1920s and 1930s, Kurds several times unsuccessfully rebelled against the Turkish authorities.

In August 1984, the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) declared war on the Turkish authorities, which continues today. Until 1999, the PKK made the most radical demand - the proclamation of a single and independent Kurdistan, uniting the Kurdish territories that are now part of the state borders of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

Since 1999, the PKK has put forward requirements that are close and understandable to the bulk of the Kurdish population, namely: granting autonomy, preserving national identity, practical equalization of Kurds in rights with the Turks, opening of national schools and introduction of Kurdish TV and radio broadcasting.

Armenian separatism

Orange: areas overwhelmingly populated by Armenians (Republic of Armenia: 98%;[10] Nagorno-Karabakh: 99%; Javakheti: 95%)

Yellow: Historically Armenian areas with presently no or insignificant Armenian population (Western Armenia and Nakhichevan)

Western Armenia (Western Armenian: Արեւմտեան Հայաստան, Arevmdian Hayasdan), located in Western Asia, is a term used to refer to eastern parts of Turkey (formerly the Ottoman Empire) that were part of the historical homeland of the Armenians.[11] Western Armenia, also referred to as Byzantine Armenia, emerged following the division of Greater Armenia between the Byzantine Empire (Western Armenia) and Sassanid Persia (Eastern Armenia) in 387 AD.

The area was conquered by the Ottomans in the 16th century during the Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555) against their Iranian Safavid arch-rivals. Being passed on from the former to the latter, Ottoman rule over the region became only decisive after the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1623–1639.[12] The area then became known as Turkish Armenia or Ottoman Armenia. During the 19th century, the Russian Empire conquered all of Eastern Armenia from Iran,[13] and also some parts of Turkish Armenia, such as Kars. The region's Armenian population was affected during the widespread massacres of Armenians in the 1890s.

The Armenians living in their ancestral lands were exterminated or deported by Ottoman forces during the 1915 Armenian Genocide and over the following years. The systematic destruction of Armenian cultural heritage, which had endured over 4000 years,[14][15] is considered an example of cultural genocide.[16][17]

Only assimilated and crypto-Armenians live in the area today, and some irredentist Armenians claim it as part of United Armenia. The most notable political party with these views is the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.

Laz separatism

The majority of Laz community refrains from speaking up identity-related demands believing that these efforts would strengthen separatist groups and divide the national Turkish identity.[18][19][20][21][22] However Turkey’s Laz people are awakening to their language and culture, though it is still premature to speak of a Laz Renaissance. Amid the reform process in Turkey, the Laz, too, have embarked on a journey to rediscover their culture. In the eastern Black Sea towns of Pazar, Ardesen, Camlihemsin, Findikli, Arhavi, Hopa and Borcka, the are population swells natives of the region return home.[23] The Laz Language is in no way a part of the Georgian language, neither linguistically, nor as a dialect of the Georgian. The Laz community objects to and rejects any political terminologies such as Kartvelian Language. These terminologies foreground the Georgian language and disregard the Mingelian and Laz language as a written language. As a result of this, the Laz and Mingrelian literature is ignored and is even termed as separatist literature and has become subject of ridicule.[24] The Laz are shifting to the Turkish of Trebizond.[25][26][27][28][29]

The population of Lazistan was made up of Sunni Muslim Laz, Turks, and Hemshin people. The Christian population were around and made up of Pontic Greeks and Armenian Apostolic Christians.

After the Ottoman conquest of Trebizond Empire and later Ottoman invasion of Guria in 1547, Laz populated area known as Lazia (Pontus) became its own distinctive area (sanjak) as part of eyalet of Trabzon, under the administration of a Governor who governed from the town of Rizaion (Rize). His title was "Lazistan Mutasserif"; in other words "Governor of Lazistan". The Lazistan sanjak was divided into cazas, namely those of: Ofi, Rizaion, Athena, Hopa, Gonia and Batum.

Not only the Pashas (governors) of Trabzon until the 19th century, but real authority in many of the cazas (districts) of each sanjak by the mid-17th century lay in the hands of relatively independent native Laz derebeys ("valley-lords"), or feudal chiefs who exercised absolute authority in their own districts, carried on petty warfare with each other, did not owe allegiance to a superior and never paid contributions to the sultan. This state of insubordination was not really broken until the assertion of Ottoman authority during the reforms of the Osman Pasha in 1850s.

In 1547, Ottomans acquired the coastal fortress of Gonia, which served as capital of Lazistan; then Batum until it was acquired by the Russians in 1878, throughout the Russo-Turkish War, thereafter, Rize became the capital of the sanjak. The Muslim Lazs living near the war zones in Batumi Oblast were subjected to ethnic cleansing; many Lazes living in Batumi fled to the Ottoman Empire, settling along the southern Black Sea coast to the east of Samsun and Marmara region.

Around 1914 Ottoman policy towards the Christian population shifted; state policy was since focused to the forceful migration of Christian Pontic Greek and Laz population living in coastal areas to the Anatolian hinterland. In the 1920s Christian population of the Pontus were expelled to Greece.

In 1917, after the Russian Revolution, Lazs became citizents of Democratic Republic of Georgia, and eventually became Soviet citizens after the Red Army invasion of Georgia in 1921. Simultaneously, a treaty of friendship was signed in Moscow between Soviet Russia and the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, whereby southern portions of former Batum Oblast - later known as Artvin, was awarded to Turkey, which renounced its claims to Batumi.

The autonomous Lazistan sanjak existed until the end of the empire in 1923. The designation of the term of Lazistan was officially banned in 1926, by the Kemalists.[30] Lazistan was divided between Rize and Artvin provinces.

See also

References

- https://ahvalnews.com/turkey-nationalism/renewed-turkish-nationalism-silences-ethnic-minorities

- https://merip.org/1996/09/kurds-turks-and-the-alevi-revival-in-turkey/

- https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057%2F9780230513082_6

- https://journals.openedition.org/ejts/4008

- https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2019/08/12/473508/state-turkish-kurdish-conflict/

- https://www.refworld.org/docid/469f38e91e.html

- https://fas.org/asmp/profiles/turkey_background_kurds.htm

- https://www.amazon.com.br/Secession-Turkey-Abdullah-Kurdistan-conflict/dp/1157615732

- https://merip.org/1996/09/kurds-turks-and-the-alevi-revival-in-turkey/

- "2011 Census Results" (PDF). armstat.am. National Statistical Service of Republic of Armenia. p. 144.

- Myhill, John (2006). Language, Religion and National Identity in Europe and the Middle East: A historical study. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-272-9351-0.

- Wallimann, Isidor; Dobkowski, Michael N. (March 2000). Genocide and the Modern Age: Etiology and Case Studies of Mass Death. ISBN 9780815628286. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond pp 728–729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- Marie-Aude Baronian; Stephan Besser; Yolande Jansen (2007). Diaspora and Memory: Figures of Displacement in Contemporary Literature, Arts and Politics. Rodopi. p. 174. ISBN 9789042021297.

- Shirinian, Lorne (1992). The Republic of Armenia and the rethinking of the North-American Diaspora in literature. E. Mellen Press. p. ix. ISBN 9780773496132.

This date is important, for it marks the beginning of the Armenian Genocide, which destroyed the over two-thousand-year Armenian presence in historical, Western Armenia.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2008). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 9781412835923.

- Jones, Adam (2013). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 9781134259816.

- https://isaconf.confex.com/isaconf/forum2012/webprogram/Paper15701.html

- Sarigil, Zeki (2012). "Ethnic Groups at 'Critical Junctures': The Laz vs. Kurds". Middle Eastern Studies. 48 (2): 269–286. doi:10.1080/00263206.2011.652778. hdl:11693/12314. S2CID 53584439.

- https://www.hrw.org/reports/2000/turkey2/Turk009-04.htm

- Solomon, Thomas (2017). "Who Are the Laz? Cultural Identity and the Musical Public Sphere on the Turkish Black Sea Coast". The World of Music. 6 (2): 83–113. JSTOR 44841947.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268083536_Between_assimilation_and_survival_Laz_community_in_Turkey

- https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/12/laz-people-of-turkey-awaken.html

- https://abkhazworld.com/aw/statements/178-laz-intellectuals-explain-their-view-of-laz-ethnicity

- https://www.rferl.org/a/1088963.html

- https://www.cairn.info/revue-l-europe-en-formation-2013-1-page-143.htm#

- https://tcf.org/content/report/turkeys-troubled-experiment-secularism/

- https://www.refworld.org/docid/3df4beb524.html

- http://repository.bilkent.edu.tr/bitstream/handle/11693/12314/ethnic_groups.pdf?sequence=1

- Thys-Şenocak, Lucienne. Ottoman Women Builders. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006. Print.

.png.webp)