Arabs in Turkey

Turkish Arabs (Turkish: Türkiye Arapları, Arabic: عرب تركيا) refers to the 1.5-2 million citizens and residents of Turkey who are ethnically of Arab descent. They are the second-largest minority in the country after the Kurds, and are concentrated in the south. Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011, millions of Arab Syrian refugees have sought refuge in Turkey.[11]

عرب تركيا | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 1,500,000 - 2,000,000 (2011)[1][2] (Pre-Syrian Civil War Arab minority) 4,000,000 - 5,000,000 (2017)[3][4][5][6][4][7][5][8] (Including Syrian refugees) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Mainly Southeastern Anatolia Region | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic, Turkish[9] | |

| Religion | |

| Predominately Sunni Islam Minority Alawism, Orthodox Christianity and Judaism [10] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Arab diaspora |

Background

Besides the large communities of both foreign and Turkish Arabs in Istanbul and other large cities, most live in the south and southeast.[12]

Turkish Arabs are mostly Muslims living along the southeastern border with Syria and Iraq in the following provinces: Batman, Bitlis, Gaziantep, Hatay, Mardin, Muş, Siirt, Şırnak, Şanlıurfa, Mersin and Adana. Many Bedouin tribes, in addition to other Arabs who settled there, arrived before Turkic tribes came to Anatolia from Central Asia in the 11th century. Many of these Arabs have ties to Arabs in Syria, especially in the city of Raqqa. Arab society in Turkey has been subject to Turkification, yet some speak Arabic in addition to Turkish. The Treaty of Lausanne ceded to Turkey large areas that had been part of Ottoman Syria, especially in Aleppo Vilayet.[13]

Besides a significant Shafi'i Sunni population, about 300,000 to 350,000 are Alawites[14] (distinct from Alevism). About 18,000 Arab Christians[10] belong mostly to the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch. There are also few Arab Jews in Hatay and other Turkish parts of the former Aleppo Vilayet, but this community has shrank considerably since the late 1940s, mostly due to migration to Israel and other parts of Turkey.

History

Pre-Islamic period

Arabs presence in what used to be called Asia Minor, dates back to the Hellenistic period. The Arab dynasty of the Abgarids were rulers of the Kingdom of Osroene, with its capital in the ancient city of Edessa (Modern day city of Urfa). According to Retsö, The Arabs presence in Edessa dates back to AD 49.[15] In addition, the Roman author Pliny the Elder refers to the natives of Osroene as Arabs and the region as Arabia.[16] In the nearby Tektek Mountains, Arabs seem to have made it the seat of the governors of 'Arab.[17] An early Arab figure who flourished in Anatolia is the 2nd century grammarian Phrynichus Arabius, specifically in the Roman province of Bithynia. Another example, is the 4th century Roman politician Domitius Modestus who was appointed by Emperor Julian to the position of Praefectus urbi of Constantinople (Modern day Istanbul). And under Emperor Valens, he became Praetorian Prefect of the East whose seat was also in Constantinople. In the 6th century, The famous Arab poet Imru' al-Qais journeyed to Constantinople in the time of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. On his way back, it is said that he died and was buried at Ancyra (Modern day Ankara) in the Central Anatolia Region.[18]

The age of Islam

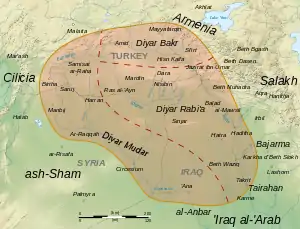

In the early Islamic conquests, the Rashidun Caliphate successful campaigns in the Levant lead to the fall of the Ghassanids. The last Ghassanid king Jabalah ibn al-Aiham with as many as 30,000 Arab followers managed to avoid the punishment of the Caliph Umar by escaping to the domains of the Byzantine Empire.[19] King Jabalah ibn al-Aiham established a government-in-exile in Constantinople[20] and lived in Anatolia until his death in 645. Following the early Muslim conquests, Asia Minor became the main ground for the Arab-Byzantine wars. Among those Arabs who were killed in the wars was Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Abu Ayyub was buried at the walls of Constantinople. Centuries later, after the Ottomans conquest of the city, a tomb above Abu Ayyub's grave was constructed and a mosque built by the name of Eyüp Sultan Mosque. From that point on, the area became known as the locality of Eyup by the Ottoman officials. Another instance of Arab presence in what is nowadays Turkey, is the settlement of Arab tribes in the 7th century in the region of Al-Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia), that partially encompasses Southeastern Turkey. Among those tribes are the Banu Bakr, Mudar, Rabi'ah ibn Nizar and Banu Taghlib.

Demographics

| Year | As first language | As second language | Total | Turkey's population | % of Total speakers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | 134,273 | - | 134,273 | 13,629,488 | 0.99 |

| 1935 | 153,687 | 34,028 | 187,715 | 16,157,450 | 1.16 |

| 1945 | 247,294 | 60,061 | 307,355 | 18,790,174 | 1.64 |

| 1950 | 269,038 | - | 269,038 | 20,947,188 | 1.28 |

| 1955 | 300,583 | 95,612 | 396,195 | 24,064,763 | 1.65 |

| 1960 | 347,690 | 134,962 | 482,652 | 27,754,820 | 1.74 |

| 1965 | 365,340 | 169,724 | 533,264 | 31,391,421 | 1.70 |

According to a Turkish study based on a large survey in 2006, 0.7% of the total population in Turkey were ethnically Arab.[22] The population of Arabs in Turkey varies according to different sources. A 1995 American estimate put the numbers between 800,000 and 1 million.[2] According to Ethnologue, in 1992 there were 500,000 people with Arabic as their mother tongue in Turkey.[23] Another Turkish study estimated the Arab population to be between 1.1 and 2.4%.[24]

In a 2020 interview with Al Jazeera, the prominent Turkish politician Yasin Aktay estimated the number of Arabs in Turkey at nine million (or 10% of Turkey's population), half of them from other countries.[25]

Notable people

- Emine Erdoğan, wife of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, whose family is from Siirt.[26]

- Yasin Aktay, aide to President Erdoğan.

- Hüseyin Çelik, politician, Arab father.[27]

- Murat Yıldırım, actor, Arab mother.[28]

- Murathan Mungan, author, Arab father.[29]

- Nicholas Kadi, actor of Iraqi descent.[30]

- Mihrac Ural, militant and leader of the Syrian Resistance.

- Selin Sayek Böke, politician.

- Sertab Erener, singer, songwriter and composer.

- Pınar Deniz, actress.

- Selin Şekerci, actress.

- İbrahim Tatlıses, actor and singer.[31]

- Nur Yerlitaş, fashion designer.

- Ahmet Düverioğlu, basketball player.

- Mert Fırat, actor and screenwriter.

- Jehan Barbur, singer and songwriter.

- Atiye, pop singer of Arab descent.

- Selami Şahin, singer and songwriter.

- CZN Burak, chef and restaurateur.

See also

References

- "Arabs: Turkey's new minority". Al-Monitor. 12 September 2014.

- Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Turkey: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1995.

- (UNHCR), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response". UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response. Archived from the original on 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- http://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/11298 The Iraqi Refugee Crisis and Turkey: a Legal Outlook

- "Turkey's demographic challenge". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- "UNHCR Syria Regional Refugee Response/ Turkey". UNHCR. 31 December 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- "The Impact of Syrian Refugees on Turkey". www.washingtoninstitute.org. Retrieved 2016-12-18.

- Ozdemir, Soner Cagaptay, Oya Aktas and Cagatay. "The Impact of Syrian Refugees on Turkey". Soner Cagaptay.

- Lahdo, Ablahad (2009). "The Arabic Dialect of Tillo in the Region of Siirt" (PDF). Uppsala Universitet, Department of African and Asian Languages. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Christen in der islamischen Welt – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ 26/2008)

- "Total Persons of Concern by Country of Asylum". data2. UNHCR. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Die Bevölkerungsgruppen in Istanbul (türkisch) Archived February 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Translation of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923). The original text was in French.

- Die Nusairier weltweit und in der Türkei (türkisch) Archived 2011-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Retso, Jan; Retsö, Jan (2003). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1679-1.

- MacAdam, Henry Innes; Munday, Nicholas J. (1983). "Cicero's Reference to Bostra (AD Q. FRAT. 2. 11. 3)". Classical Philology. 78 (2): 131–136. JSTOR 269718. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Drijvers, Han J. W.; Healey, John F. (1999). Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-11284-1.

- Inc, Merriam-Webster; STAFF, MERRIAM-WEBSTER; Staff, Encyclopaedia Britannica Publishers, Inc (1995). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Merriam-Webster. ISBN 978-0-87779-042-6.

- "The Origins of the Islamic State", a translation from the Arabic of the "Kitab Futuh al-Buldha of Ahmad ibn-Jabir al-Baladhuri", trans. by P. K. Hitti and F. C. Murgotten, Studies in History, Economics and Public Law, LXVIII (New York, Columbia University Press,1916 and 1924), I, 207-211

- Ghassan Resurrected, Yasmine Zahran 2006, p. 13

- Fuat Dündar, Türkiye Nüfus Sayımlarında Azınlıklar, 2000

- "Toplumsal yapı araştırması 2006" (PDF). KONDA Research and Consultancy. 2006. pp. 15–16. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 15, 2017. Retrieved May 10, 2012. .(in Turkish)

- Tu. Turkey: Languages. Accessed on 19 September 2013.

- Ali Tayyar Önder: Türkiye'nin etnik yapısı: Halkımızın kökenleri ve gerçekler. Kripto Kitaplar, Istanbul 2008, ISBN 605-4125-03-6, S. 103. (in Turkish)

- Al-Jazeera.net, 2020. مقابلة مع الجزيرة نت.. مستشار أردوغان: 10% من سكان تركيا عرب وهذه أوضاعهم. Accessed on 16 June 2020.

- "Mrs Erdogan's many friends", The Economist, 12 August 2004

- Yaklaşık 5-6 milyon Türk-Kürt evliliği var, Sabah, 2010

- "Murat Yıldırım: 'Annem Arapça, babam Kürtçe konuşur'". Akşam. 3 February 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- "Kürt değilim, kökenim Arap".

- "Nicholas Kadi, actor with Iraqi roots". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- "Tatlises rapped for using Kurdistan". kurdpress. 27 October 2013. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

Further reading

- Werner, Arnold (2000). "The Arabic dialects in the Turkish province of Hatay and the Aramaic dialects in the Syrian mountains of Qalamun: two minority languages compared". In Owens, Jonathan (ed.). Arabic as a minority language. Book Publishers. pp. 347–370. ISBN 9783110165784.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arab people in Turkey. |