Minorities in Turkey

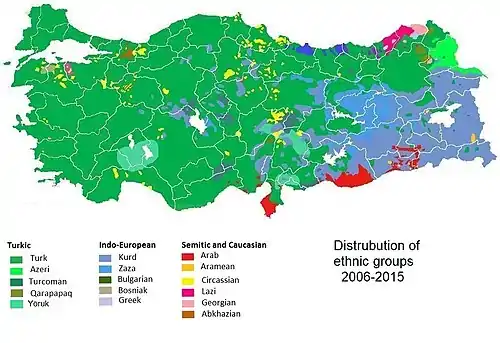

Minorities in Turkey form a substantial part of the country's population, representing an estimated 25% to 30% of the population.

Historically, in the Ottoman Empire, Islam was the official and dominant religion, with Muslims having different privileges and duties from non-Muslims.[2] Non-Muslim (dhimmi) ethno-religious[3] groups were legally identified by different millet ("nations").[2]

Following the end of World War I and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, all Ottoman Muslims were made part of the modern citizenry or the Turkish nation as the newly founded Republic of Turkey was constituted as a Muslim nation state. While Turkish nationalist policy viewed all Muslims in Turkey as Turks without exception, non-Muslim minority groups, such as Jews and Christians, were designated as "foreign nations" (millet).[3][4] Conversely, the term 'Turk' was used to denote all groups in the region who had been Islamized under Ottoman rule, especially Muslim Albanians and Slavic Muslims.[2]

The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne specified Armenians, Greeks and Jews and Christians in general as ethnic minorities (dhimmi). This legal status was not granted to Muslim minorities, such as the Kurds, which constituted the largest minority by a wide margin, nor any of the other minorities in the country. In modern Turkey, data on the ethnic makeup of the country is not officially collected, although various estimates exist. All Muslim citizens are still regarded as Turks by law, regardless of their ethnicity or language, in contrast to non-Muslim minorities, who are still grouped as "non-Turks"; the largest ethnic minority, the Kurds, who are predominantly Muslim, are therefore still classified as simply "Turks".[3][4]

The amount of ethnic minorities is considered to be underestimated by the Turkish government. Therefore, the exact number of members of ethnic groups who are also predominantly Muslim is unknown; these include Arabs, Albanians, Bosniaks, Circassians, Chechens, Kurds, Megleno-Romanians and Pontic Greeks, among other smaller groups.

Many of the minorities (including Albanians, Bosniaks, Crimean Tatars, Megleno-Romanians, and various peoples from the Caucasus, as well as some Turks) are descendants of Muslims (muhajirs) who were expelled from the lands lost by the shrinking Ottoman Empire. A majority have assimilated into and intermarried with the majority Turkish population and have adopted the Turkish language and way of life, though do not necessarily identify as Turks. Turkification and often aggressive Turkish nationalist policies strengthen these trends. Although many minorities have no official recognition, state-run TRT television and radio broadcasts minority language programs and elementary schools offer minority language classes.

Tables

| Ottoman official statistics, 1910 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanjak | Turks | Greeks | Armenians | Jews | Others | Total | |

| Istanbul (Asiatic shore) | 135,681 | 70,906 | 30,465 | 5,120 | 16,812 | 258,984 | |

| İzmit | 184,960 | 78,564 | 50,935 | 2,180 | 1,435 | 318,074 | |

| Aydin (İzmir) | 974,225 | 629,002 | 17,247 | 24,361 | 58,076 | 1,702,911 | |

| Bursa | 1,346,387 | 274,530 | 87,932 | 2,788 | 6,125 | 1,717,762 | |

| Konya | 1,143,335 | 85,320 | 9,426 | 720 | 15,356 | 1,254,157 | |

| Ankara | 991,666 | 54,280 | 101,388 | 901 | 12,329 | 1,160,564 | |

| Trabzon | 1,047,889 | 351,104 | 45,094 | - | - | 1,444,087 | |

| Sivas | 933,572 | 98,270 | 165,741 | - | - | 1,197,583 | |

| Kastamonu | 1,086,420 | 18,160 | 3,061 | - | 1,980 | 1,109,621 | |

| Adana | 212,454 | 88,010 | 81,250 | – | 107,240 | 488,954 | |

| Canakkale | 136,000 | 29,000 | 2,000 | 3,300 | 98 | 170,398 | |

| Total | 8,192,589 | 1,777,146 | 594,539 | 39,370 | 219,451 | 10,823,095 | |

| Percentage | 75.7% | 16.42% | 5.50% | 0.36% | 2.03% | ||

| Ecumenical Patriarchate statistics, 1912 | |||||||

| Total | 7,048,662 | 1,788,582 | 608,707 | 37,523 | 218,102 | 9,695,506 | |

| Percentage | 72.7% | 18.45% | 6.28% | 0.39% | 2.25% | ||

| Ottoman official statistics, 1910[6] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanjak | Turks | Greeks | Bulgarians | Others | Total | ||

| Edirne | 128,000 | 113,500 | 31,500 | 14,700 | 287,700 | ||

| Kirk Kilisse | 53,000 | 77,000 | 28,500 | 1,150 | 159,650 | ||

| Tekirdağ | 63,500 | 56,000 | 3,000 | 21,800 | 144,300 | ||

| Gallipoli | 31,500 | 70,500 | 2,000 | 3,200 | 107,200 | ||

| Çatalca | 18,000 | 48,500 | – | 2,340 | 68,840 | ||

| Constantinople | 450,000 | 260,000 | 6,000 | 130,000 | 846,000 | ||

| Total | 744,000 | 625,500 | 71,000 | 173,190 | 1,613,690 | ||

| Percentage | 46.11% | 38.76% | 4.40% | 10.74% | |||

| Ecumenical Patriarchate statistics, 1912 | |||||||

| Total | 604,500 | 655,600 | 71,800 | 337,600 | 1,669,500 | ||

| Percentage | 36.20% | 39.27% | 4.30% | 20.22% | |||

| Year | 1914 | 1927 | 1945 | 1965 | 1990 | 2005 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslims | 12,941 | 13,290 | 18,511 | 31,139 | 56,860 | 71,997 |

| Greeks | 1,549 | 110 | 104 | 76 | 8 | 3 |

| Armenians | 1,204 | 77 | 60 | 64 | 67 | 50 |

| Jews | 128 | 82 | 77 | 38 | 29 | 27 |

| Others | 176 | 71 | 38 | 74 | 50 | 45 |

| Total | 15,997 | 13,630 | 18,790 | 31,391 | 57,005 | 72,120 |

| Percentage non-Muslim | 19.1 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Turkey |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

| Sport |

|

Ethnic minorities

Abdal

Groups of nomadic and semi-nomadic itinerants found mainly in central and western Anatolia. They speak an argot of their own and follow the Alevi sect of Islam.[8]

Afghans

Afghans are one of the largest irregular migrant groups in Turkey. From the period 2003–2007, the number of Afghans apprehended were significant, with statistics almost doubling during the last year. Most had fled the War in Afghanistan. In 2005, refugees from Afghanistan numbered 300 and made a sizeable proportion of Turkey's registered migrants.[9] Most of them were spread out over satellite cities with Van and Ağrı being the most specific locations.[10] In the following years, the number of Afghans entering Turkey greatly increased, second only to migrants from Iraq; in 2009, there were 16,000 people designated under the Iraq-Afghanistan category. Despite a dramatic 50 percent reduction by 2010, reports confirmed hundreds living and working in Turkey.[11] As of January 2010, Afghans consisted one-sixth of the 26,000 remaining refugees and asylum seekers.[12] By the end 2011, their numbers are expected to surge up to 10,000, making them the largest population and surpass other groups.

Africans

Beginning several centuries ago, a number of Africans, usually via Zanzibar as Zanj and from places such as Niger, Saudi Arabia, Libya, Kenya and Sudan,[13] came to the Ottoman Empire settled by the Dalaman, Menderes and Gediz valleys, Manavgat, and Çukurova. African quarters of 19th-century İzmir, including Sabırtaşı, Dolapkuyu, Tamaşalık, İkiçeşmelik, and Ballıkuyu, are mentioned in contemporary records.[14] Due to the slave trade in the Ottoman Empire that had flourished in the Balkans, the coastal town of Ulcinj in Montenegro had its own black community.[15] As a consequence of the slave trade and privateer activity, it is told how until 1878 in Ulcinj 100 black people lived.[16] The Ottoman Army also deployed an estimated 30,000 Black African troops and cavalrymen to its expedition in Hungary during the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–18.[17]

Albanians

A 2008 report from the Turkish National Security Council (MGK) estimated that approximately 1.3 million people of Albanian ancestry live in Turkey, and more than 500,000 recognizing their ancestry, language and culture. There are other estimates however that place the number of people in Turkey with Albanian ancestry and or background upward to 5 million.[18]

However, these assumptions of the Turkish government are contested by many scholars who claim they are without any basis.[19]

Arabs

Arabs in Turkey number between 800,000 and 1 million, and they mostly live in provinces near the Syrian border, particularly the Hatay region, where they made up two thirds of the population in 1939.[20] However, including recent Syrian refugees, they make up to 5.3% of the population. Most of them are Sunni Muslims. However, there is a small group of Alawis, and another one of Arab Christians (mostly in Hatay Province) in communion with the Antiochian Orthodox Church.

Turkey experienced a large influx of Iraqis between the years of 1988 and 1991 due to both the Iran–Iraq War and the first Gulf war,[21] with around 50,000 to 460,000 Iraqis entering the country.[22]

Syrians in Turkey include migrants from Syria to Turkey, as well as their descendants. The number of Syrians in Turkey is estimated at over 3.58 million people as of April 2018,[23] and consists mainly of refugees of the Syrian Civil War.

Armenians

Armenians are indigenous to the Armenian Highlands which corresponds to the eastern half of modern-day Turkey, the Republic of Armenia, southern Georgia, western Azerbaijan, and northwestern Iran. Although in 1880 the word Armenia was banned from being used in the press, schoolbooks, and governmental establishments in Turkey and was subsequently replaced with words like eastern Anatolia or northern Kurdistan, Armenians had maintained much of their culture and heritage.[24][25][26][27][28] The Armenian population of Turkey was greatly reduced following the Hamidian massacres and especially the Armenian Genocide, when over one and half million Armenians, virtually the entire Armenian population of Anatolia, were massacred. Prior to the Genocide in 1914, the Armenian population of Turkey numbered at about 1,914,620.[29][30] The Armenian community of the Ottoman Empire before the Armenian genocide had an estimated 2,300 churches and 700 schools (with 82,000 students).[31] This figure excludes churches and schools belonging to the Protestant and Catholic Armenian parishes since only those churches and schools under the jurisdiction of the Istanbul Armenian Patriarchate and the Apostolic Church were counted.[31] After the Armenian genocide however, it is estimated that 200,000 Armenians remained in Turkey.[32] Today there are an estimated 40,000 to 70,000 Armenians in Turkey, not including the Hamshenis.[33][34]

Armenians under the Turkish Republican era were subjected to many policies which attempted to abolish Armenian cultural heritage such as the Turkification of last names, Islamification, geographical name changes, confiscation of properties, change of animal names,[35] change of the names of Armenian historical figures (i.e. the name of the prominent Balyan family were concealed under an identity of a superficial Italian family called Baliani),[36][37] and the change and distortion of Armenian historical events.[38]

Armenians today are mostly concentrated around Istanbul. The Armenians support their own newspapers and schools. The majority belong to the Armenian Apostolic faith, with much smaller numbers of Armenian Catholics and Armenian Evangelicals. The community currently functions 34, 18 schools, and 2 hospitals.[31]

Assyrians

Assyrians were once a large ethnic minority in the Ottoman Empire, but following the early 20th century Assyrian Genocide, many were murdered, deported, or ended up emigrating. Those that remain live in small numbers in their indigenous South Eastern Turkey (although in larger numbers than other groups murdered in Armenian or Greek genocides) and Istanbul. They number around 30,000 and are part of the Syriac Orthodox Church, Chaldean Catholic Church and Church of the East.

Australians

There are as many as 12,000 Australians in Turkey.[39] Of these, the overwhelming majority are in the capital Ankara (roughly 10,000) while the remaining are in Istanbul. Australian expatriates in Turkey form one of the largest overseas Australian groups in Europe and Asia. The vast majority of Australian nationals in Turkey are Turkish Australians.

Azerbaijanis

It is hard to determine how many ethnic Azeris currently reside in Turkey because ethnicity is a rather fluid concept in this country.[40] Up to 300,000 of Azeris who reside in Turkey are citizens of Azerbaijan.[41] In the Eastern Anatolia Region, Azeris are sometimes referred to as acem (see Ajam) or tat.[42] They currently are the largest ethnic group in the city of Iğdır[43] and second largest ethnic group in Kars.[44]

Bosniaks

Today, the existence of Bosniaks in the country is evident everywhere. In cities like İstanbul, Eskişehir, Ankara, İzmir, or Adana, one can easily find districts, streets, shops or restaurants with names such as Bosna, Yenibosna, Mostar, or Novi Pazar.[45] However, it is extremely difficult to estimate how many Bosniaks live in this country. Some Bosnian researchers believe that the number of Bosniaks in Turkey is about two million. [46]

Britons

There are at least 34,000 Britons in Turkey.[47] They consist mainly of British citizens married to Turkish spouses, British Turks who have moved back into the country, students and families of long-term expatriates employed predominately in white-collar industry.[48]

Bulgarians

People identifying as Bulgarian include a large number of the Pomak and a small number of Orthodox Bulgarians.[49][50][51][52][53] According to Ethnologue at present 300,000 Pomaks in European Turkey speak Bulgarian as their mother tongue.[54] It is very hard to estimate the number of Pomaks along with the Turkified Pomaks who live in Turkey, as they have blended into the Turkish society and have been often linguistically and culturally dissimilated.[55] According to Milliyet and Turkish Daily News reports, the number of Pomaks along with the Turkified Pomaks in the country is about 600,000.[56][55] According to the Bulgarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Bulgarian Orthodox Christian community in Turkey stands at 500 members.[57]

Central Asian peoples

Turkey received refugees from among the Pakistan-based Kazakhs, Turkmen, Kirghiz, and Uzbeks numbering 3,800 originally from Afghanistan during the Soviet–Afghan War.[58] Kayseri, Van, Amasva, Cicekdag, Gaziantep, Tokat, Urfa, and Serinvol received via Adana the Pakistan-based Kazakh, Turkmen, Kirghiz, and Uzbek refugees numbering 3,800 with UNHCR assistance.[59]

Kazakhs

They are about 30,000 Kazakh people living in Zeytinburnu-Istanbul. It is known that there are Kazakh people in other parts of Turkey, for instance Manisa, Konya. In 1969 and 1954 Kazakhs migrated into Anatolia's Salihli, Develi and Altay regions.[60] Turkey became home to refugee Kazakhs.[61] The Kazakh Turks Foundation (Kazak Türkleri Vakfı) is an organization of Kazakhs in Turkey.[62] Kazakhs in Turkey came via Pakistan and Afghanistan.[63] Kazak Kültür Derneği (Kazakh Culture Associration) is a Kazakh diaspora organization in Turkey.[64]

Kyrgyz

Turkey's Lake Van area is the home of Kyrgyz refugees from Afghanistan.[65] Turkey became a destination for Kyrgyz refugees due to the Soviet–Afghan War from Afghanistan's Wakhan area[66] 500 remained and did not go to Turkey with the others.[67] Friendship and Culture Society of Kyrgyzstan (Кыргызстан Достук жана Маданият Коому) (Kırgızistan Kültür ve Dostluk Derneği Resmi Sitesi) is a Kyrgyz diaspora organization in Turkey.[68]

They were airlifted in 1982 from Pakistan where they had sought refugee after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan at the end of 1979. Their original home was at the eastern end of the Wakhan Corridor, in the Pamirs, bordering on China. It is not known how many Kyrgyz still live in Van and how many have moved on to other parts of Turkey.

Megleno-Romanians

Around 5,000 Megleno-Romanians live in Turkey.[69]

Uzbeks

Turkey is home to 45,000 Uzbeks.[70] In the 1800s Konya's north Bogrudelik was settled by Tatar Bukharlyks. In 1981 Afghan Turkestan refugees in Pakistan moved to Turkey to join the existing Kayseri, Izmir, Ankara, and Zeytinburnu based communities.[60] Turkish based Uzbeks have established links to Saudi-based Uzbeks.[71]

Uyghurs

Turkey is home to 50,000 Uyghurs.[72] A community of Uyghurs live in Turkey.[73][74] Kayseri received Uyghurs numbering close to 360 via the UNHCR in 1966–1967 from Pakistan.[75] The Turkey-based Uyghur diaspora had a number of family members among Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan, India, and Pakistan based Uyghurs who stayed behind while the UNHCR and government of Turkey had Kayseri receive 75 Uyghurs in 1967 and 230 Uyghurs in 1965 and a number in 1964 under Alptekin and Bughra.[76] We never call each other Uyghur, but only refer to ourselves as East Turkestanis, or Kashgarlik, Turpanli, or even Turks.- according to some Uyghurs born in Turkey.[77][78]

A community of Uyghurs live in Istanbul. Tuzla and Zeytinburnu mosques are used by the Uyghurs in Istanbul.[79][80] Piety is a characteristic of among Turkey dwelling Uyghurs.[81][82]

Istanbul's districts of Küçükçekmece, Sefaköy and Zeytinburnu are home to Uyghur communities.[83] Eastern Turkistan Education and Solidarity Association is located in Turkey.[84] Abdurahmon Abdulahad of the East Turkistan Education Association supported Uzbek Islamists who protested against Russia and Islam Karimov's Uzbekistan government.[85] Uyghurs are employed in Küçükçekmece and Zeytinburnu restaurants.[86][87] East Turkistan Immigration Association,[88] East Turkistan Culture and Solidarity Association,[89] and Eastern Turkistan Education and Solidarity Association are Uyghur diaspora organizations in Turkey.[90]

Circassians

According to Milliyet, there are approximately 2.5 million Circassians in Turkey.[56] According to the EU reports there are three to five million Circassians in Turkey.[91] The closely related ethnic groups Abazins (10,000[92]) and Abkhazians (39,000[93]) are also often counted among them. Circassians are a Caucasian immigrant people, and although the Circassians in Turkey were forced to forget their language and assimilate into Turkish, a small minority still speak their native Circassian languages as it is still spoken in many Circassian villages, and the group that preserved their language the best are the Kabardians.[94] With the rise of Circassian nationalism in the 21st century, Circassians in Turkey, especially the young, have started to study and learn their language. The Circassians in Turkey are mostly Sunni Muslims of Hanafi madh'hab, although other thoughts such as Shafi'i madh'hab, non-denominationalism and Qur'anism are also seen among Circassians. The largest association of Circassians in Turkey,[95] KAFFED, is the founding member of the International Circassian Association (ICA).[96]

Crimean Tatars

Before the 20th century, Crimean Tatars had immigrated from Crimea to Turkey in three waves: First, after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 1783; second, after the Crimean War of 1853–56; third, after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78.[97] The official number of Crimean Tatars is 150,000 (in the center of Eskişehir) but the real population (in the whole of Turkey) may be a few million. They mostly live in Eskişehir Province [98] and Kazan-Ankara.

Dagestani peoples

Various ethnic groups from Dagestan are present in Turkey. Dagestani peoples live in villages in the provinces like Balıkesir, Tokat and also scattered in other parts of the country. A majority among them are Nogais; Lezgins and Avars are other significant ethnic groups. Kumyks are also present.

Filipinos

There were 5,500 Filipinos in Turkey as of 2008, according to estimates by the Commission on Filipinos Overseas and the Philippine embassy in Ankara.[100] Out of those, most are recorded as maids and "overseas workers" employed in households of diplomatic communities and elite Turkish families.[101] Moreover, ten percent or approximately 500 Filipinos in Turkey are skilled workers and professionals working as engineers, architects, doctors and teachers.[101] Most of the Filipinos reside in Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir, Antalya and nearby surrounding areas.[100]

Georgians

There are approximately 1 million people of Georgian ancestry in Turkey according to the newspaper Milliyet.[56] Georgians in Turkey are mostly Sunni Muslims of Hanafi madh'hab. Immigrant Georgians are called "Chveneburi", but autochthonous Muslim Georgians use this term as well. Muslim Georgians form the majority in parts of Artvin Province east of the Çoruh River. Immigrant Muslim groups of Georgian origin, found scattered in Turkey, are known as Chveneburi. The smallest Georgian group are Catholics living in Istanbul.

Germans

There are over 50,000 Germans living in Turkey, primarily Germans married to Turkish spouses, employees, retirees and long-term tourists who buy properties across the Turkish coastline, often spending most of the year in the country.[102] In addition, many Turkish Germans have also returned and settled.

Greeks

The Greeks constitute a population of Greek and Greek-speaking Eastern Orthodox Christians who mostly live in Istanbul, including its district Princes' Islands, as well as on the two islands of the western entrance to the Dardanelles: Imbros and Tenedos (Turkish: Gökçeada and Bozcaada). Some Greek-speaking Byzantine Christians have been assimilated over the course of the last one thousand years.

They are the remnants of the estimated 200,000 Greeks who were permitted under the provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne to remain in Turkey following the 1923 population exchange,[103] which involved the forcible resettlement of approximately 1.5 million Greeks from Anatolia and East Thrace and of half a million Turks from all of Greece except for Western Thrace. After years of persecution (e.g. the Varlık Vergisi and the Istanbul Pogrom), emigration of ethnic Greeks from the Istanbul region greatly accelerated, reducing the 119,822 [104]-strong Greek minority before the attack to about 7,000 by 1978.[105] The 2008 figures released by the Turkish Foreign Ministry places the current number of Turkish citizens of Greek descent at the 3,000–4,000 mark.[106] According to Milliyet there are 15,000 Greeks in Turkey,[56] while according to Human Rights Watch the Greek population in Turkey was estimated at 2,500 in 2006.[107] According to the same source, the Greek population in Turkey was collapsing as the community was by then far too small to sustain itself demographically, due to emigration, much higher death rates than birth rates and continuing discrimination.[107] In recent years however, most notably since the economic crisis in Greece, the trend has reversed. A few hundred to over a thousand Greeks now migrate to Turkey yearly for employment or educational purposes.[108][109]

Christian Greeks were forced to migrate. Muslim Greeks live in Turkey today. They live in cities of Trabzon and Rize. Pontic Greeks have Greek ancestry and speak the Pontic Greek dialect, a distinct form of the standard Greek language which, due to the remoteness of Pontus, has undergone linguistic evolution distinct from that of the rest of the Greek world. The Pontic Greeks had a continuous presence in the region of Pontus (modern-day northeastern Turkey), Georgia, and Eastern Anatolia from at least 700 BC until 1922.

Since 1924, the status of the Greek minority in Turkey has been ambiguous. Beginning in the 1930s, the government instituted repressive policies forcing many Greeks to emigrate. Examples are the labour battalions drafted among non-Muslims during World War II as well as the Fortune Tax levied mostly on non-Muslims during the same period. These resulted in financial ruination and death for many Greeks. The exodus was given greater impetus with the Istanbul Pogrom of September 1955 which led to thousands of Greeks fleeing the city, eventually reducing the Christian Greek population to about 7,000 by 1978 and to about 2,500 by 2006 before beginning to increase again after 2008.

Iranians

Shireen Hunter noted in a 2010 publication that there were some 500,000 Iranians in Turkey.[110]

Jews

There have been Jewish communities in Asia Minor since at least the 5th century BC and many Spanish and Portuguese Jews expelled from Spain came to the Ottoman Empire (including regions part of modern Turkey) in the late 15th century. Despite emigration during the 20th century, modern-day Turkey continues to have a small Jewish population of about 20,000.[56]

Karachay

Karachay people live in villages concentrated in Konya and Eskişehir.

Kurds

.png.webp)

Ethnic Kurds are the largest minority in Turkey, composing around 20% of the population according to Milliyet, 19% of the total populace or c. 14 million people according to the CIA World Factbook, and as much as 23% according to Kurdologist David McDowall.[1][112] Unlike the Turks, the Kurds speak an Iranian language. There are Kurds living all over Turkey, but most live to the east and southeast of the country, from where they originate.

In the 1930s, Turkish government policy aimed to forcibly assimilate and Turkify local Kurds. Since 1984, Kurdish resistance movements included both peaceful political activities for basic civil rights for Kurds within Turkey, and violent armed rebellion for a separate Kurdish state.[113]

Laz

Most Laz people today live in Turkey, but the Laz minority group has no official status in Turkey. Their number today is estimated at 2,250,000.[114] The Laz are Sunni Muslims. Only a minority are bilingual in Turkish and their native Laz language which belongs to the Kartvelian group. The number of the Laz speakers is decreasing, and is now limited chiefly to the Rize and Artvin areas. The historical term Lazistan — formerly referring to a narrow tract of land along the Black Sea inhabited by the Laz as well as by several other ethnic groups — has been banned from official use and replaced with Doğu Karadeniz (which also includes Trabzon). During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, the Muslim population of Russia near the war zones was subjected to ethnic cleansing; many Lazes living in Batumi fled to the Ottoman Empire, settling along the southern Black Sea coast to the east of Samsun.

Levantines

Levantines continue to live in Istanbul (mostly in the districts of Galata, Beyoğlu and Nişantaşı), İzmir (mostly in the districts of Karşıyaka, Bornova and Buca), and the lesser port city Mersin where they had been influential for creating and reviving a tradition of opera.[115] Famous people of the present-day Levantine community in Turkey include Maria Rita Epik, Franco-Levantine Caroline Giraud Koç and Italo-Levantine Giovanni Scognamillo.

Meskhetian Turks

There is a community of Meskhetian Turks (Ahiska Turks) in Turkey.[116]

Chechens and Ingush

Chechens in Turkey are Turkish citizens of Chechen descent and Chechen refugees living in Turkey. Chechens and Ingush live in the provinces of Istanbul, Kahramanmaraş, Mardin, Sivas, and Muş.

Ossetians

Ossetians emigrated from North Ossetia since the second half of the 19th century, end of Caucasian War. Today, the majority of them live in Ankara and Istanbul. There are 24 Ossetian villages in central and eastern Anatolia. The Ossetians in Turkey are divided into three major groups, depending on their history of immigration and ensuing events: those living in Kars (Sarıkamış) and Erzurum, those in Sivas, Tokat and Yozgat and those in Muş and Bitlis.[117]

Poles

There are only 4,000 ethnic Poles in Turkey who have been assimilated into the main Turkish culture. The immigration did start during the Partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Józef Bem was one of the first immigrants and Prince Adam Jerzy Czartoryski founded Polonezköy in 1842. Most Poles in Turkey live in Polonezköy, Istanbul.

Roma

The Roma in Turkey number approximately 700,000 according to Milliyet.[56] Sulukule is the oldest Roma settlement in Europe. By different Turkish and Non-Turkish estimates the number of Romani is up to 4 or 5 million[118][119] while according to a Turkish source, they are only 0.05% of Turkey's population (or roughly persons).[120] The descendants of the Ottoman Roma today are known as Xoraxane Roma and are of the Islamic faith.[121]

Russians

Russians in Turkey number about 50,000 citizens.[122] Russians began migrating to Turkey during the first half of the 1990s. Most were fleeing the economic problems prevalent after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. During this period, many Russian immigrants intermarried and assimilated with Turkish locals, giving rise to a rapid increase in mixed marriages.[122] There is a Russian Association of Education, Culture and Cooperation which aims to expand Russian language and culture in Turkey as well as promote the interests of the community.

Serbs

In the 1965 Census 6,599 Turkish citizen spoke Serbian as a first language and another 58,802 spoke Serbian as a second language.[123]

Zazas

The Zazas are a people in eastern Turkey who natively speak the Zaza language.[124] Their heartland, the Dersim region, consists of Tunceli, Bingöl provinces and parts of Elazığ, Erzincan and Diyarbakır provinces..[125][126] Their language Zazaki is a language spoken in eastern Anatolia between the rivers Euphrates and Tigris. It belongs to the northwest-Iranian group of the Iranian language branch of the Indo-European language family. The Zaza language is related to Kurdish, Persian and Balōchi. An exact indication of the number of Zaza speakers is unknown. Internal Zaza sources estimate the total number of Zaza speakers at 3 to 6 million.[127][128]

Religious minorities

Atheists

In Turkey, Atheism is the biggest group after Islam. The percentage of atheists according to polls apparently rose from about 2% in 2012[129] to approximately 3% in 2018 KONDA Survey.[130]

Bahá'í

Turkish cities Edirne and İstanbul are in the holy places of this religion. Estimate Bahá'í population in Turkey is 10,000 (2008) [131]

Christians

Christianity has a long history in Anatolia which, nowadays part of the Republic of Turkey's territory, was the birthplace of numerous Christian Apostles and Saints, such as Apostle Paul of Tarsus, Timothy, St. Nicholas of Myra, St. Polycarp of Smyrna and many others. Two out of the five centers (Patriarchates) of the ancient Pentarchy were located in present-day Turkey: Constantinople (Istanbul) and Antioch (Antakya). All of the first seven Ecumenical Councils which are recognized by both the Western and Eastern churches were held in present-day Turkey. Of these, the Nicene Creed, declared with the First Council of Nicaea (İznik) in 325, is of utmost importance and has provided the essential definitions of present-day Christianity.

Today the Christian population of Turkey estimated more than 150,000, includes an estimated 70,000 Armenian Orthodox,[132] 35,000 Roman Catholics, 17,000 Syriac Orthodox, 8,000 Chaldean Catholic, 3,000–4,000 Greek Orthodox, 10,000–18,000 Antiochian Greeks[133][134] and smaller numbers of Bulgarians, Georgians, and ethnic Turkish Protestants.

Orthodox Christians

Orthodox Christianity forms a tiny minority in Turkey, comprising far less than one tenth of one percent of the entire population. The provinces of Istanbul and Hatay, which includes Antakya, are the main centres of Turkish Christianity, with comparatively dense Christian populations, though they are very small minorities. The main variant of Christianity present in Turkey is the Eastern Orthodox branch, focused mainly in the Greek Orthodox Church.

Roman Catholics

There are around 35,000 Catholics, constituting 0.05% of the population. The faithful follow the Latin, Byzantine, Armenian and Chaldean Rite. Most Latin Rite Catholics are Levantines of mainly Italian or French background, although a few are ethnic Turks (who are usually converts via marriage to Levantines or other non-Turkish Catholics). Byzantine, Armenian, and Chaldean rite Catholics are generally members of the Greek, Armenian, and Assyrian minority groups respectively. Turkey's Catholics are concentrated in Istanbul.

In February 2006, Catholic priest Andrea Santoro, an Italian missionary working in Turkey for 10 years, was shot twice at his church near the Black Sea.[135] He had written a letter to the Pope asking him to visit Turkey.[136] Pope Benedict XVI visited Turkey in November 2006.[137] Relations had been rocky since Pope Benedict XVI had stated his opposition to Turkey joining the European Union.[138] The Council of Catholic Bishops met with the Turkish prime minister in 2004 to discuss restrictions and difficulties such as property issues.[139] More recently, Bishop Luigi Padovese, on June 6, 2010, the Vicar Apostolic of Turkey, was killed.

Protestants

Protestants comprise far less than one tenth of one percent of the population of Turkey. Even so, there is an Alliance of Protestant Churches in Turkey.[140][141] The constitution of Turkey recognizes freedom of religion for individuals. The Armenian Protestants own three Istanbul Churches from the 19th century.[141] On 4 November 2006, a Protestant place of worship was attacked with six Molotov cocktails.[142] Turkish media have criticized Christian missionary activity intensely.[143]

There is an ethnic Turkish Protestant Christian community most of them came from recent Muslim Turkish backgrounds, rather than from ethnic minorities.[144][145][146][147]

Jews

There have been Jewish communities in Asia Minor since at least the 5th century BC and many Spanish and Portuguese Jews expelled from Spain were welcomed to the Ottoman Empire (including regions part of modern Turkey) in the late 15th century. Despite emigration during the 20th century, modern-day Turkey continues to have a small Jewish population. There is a small Karaite Jewish population numbering around 100. Karaite Jews are not considered Jews by the Turkish Hakhambashi.

Alawites

The exact number of Alawites in Turkey is unknown, but there were 185 000 Alawites in 1970.[148] As Muslims, they are not recorded separately from Sunnis in ID registration. In the 1965 census (the last Turkish census where informants were asked their mother tongue), 180,000 people in the three provinces declared their mother tongue as Arabic. However, Arabic-speaking Sunni and Christian people are also included in this figure.

Alawites traditionally speak the same dialect of Levantine Arabic with Syrian Alawites. Arabic is best preserved in rural communities and Samandağ. Younger people in Çukurova cities and (to a lesser extent) in İskenderun tend to speak Turkish. Turkish spoken by Alawites is distinguished by Alawites and non-Alawites alike with its particular accents and vocabulary. Knowledge of Arabic alphabet is confined to religious leaders and men who had worked or studied in Arab countries.

Alevis

Alevis are the biggest religious minority in Turkey. Nearly 15%[149]-25% of all Turkish population is in this group. They are mainly Turk but there are significant Kurd and Zaza populations who are Alevi[150]

Twelvers

Twelver shia population of Turkey is nearly 3 million and most of them are Azeris. Half million of Ja'faris live in İstanbul. [151]

Yazidi

Yazidis in Turkey is in the area of the Yazidi homeland, along with Syria and Iraq. The Yazidi population in Turkey was estimated at around 22.000 in 1984.[152] Earlier figures are difficult to obtain and verify, but some estimate there were about 100.000 Yazidi in Turkey in the early years of the 20th century.[153]

Most Yazidis left the country and went abroad in the 1980s and 1990s, mostly to Germany and other European countries where they got asylum due to the persecution as an ethnic and religious minority in Turkey. The area they resided was in the south eastern area of Turkey, an area that had/has heavy PKK fighting. Now a few hundred Yazidi are believed to be left in Turkey.

See also

- Demographics of Turkey

- Languages of Turkey

- Geographical name changes in Turkey

- Human rights in Turkey

- Turkish Kurdistan

- Western Armenia

- Turkish minorities in the former Ottoman Empire

- Black people in the Ottoman Empire

- Turks in the former Soviet Union

- Black people in Turkey

- Australians in Turkey

- Britons in Turkey

- Canadians in Turkey

- Chinese people in Turkey

- Indians in Turkey

- Iraqis in Turkey

- Japanese people in Turkey

- Pakistanis in Turkey

- Russians in Turkey

- Yörüks

References

- CIA World Factbook: Turkey

- Antonello Biagini; Giovanna Motta (19 June 2014). Empires and Nations from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Century: Volume 1. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-1-4438-6193-9.

- Cagaptay, Soner (2014). Islam, Secularism and Nationalism in Modern Turkey: Who is a Turk? (Routledge Studies in Middle Eastern History). p. 70.

- Cagaptay 2014, p. 70.

- Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact on Greece. C Hurst & Co. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6.

- Pentzopoulos, Dimitri (2002). The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact on Greece. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-1-85065-702-6.

- Icduygu, A., Toktas, S., & Soner, B. A. (2008). The politics of population in a nation-building process: Emigration of non-Muslims from Turkey. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31(2), 358–389.

- Abdal by Peter Alford Andrews pages 435 to 438 in Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey / compiled and edited by Peter Alford Andrews, with the assistance of Rüdiger Benninghaus (Wiesbaden : Dr. Ludwig Reichert, 1989) ISBN 3-88226-418-7

- UNHCR Ankara Office

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-06-01. Retrieved 2010-02-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.todayszaman.com/tz-web/detaylar.do?load=detay&link=205790

- http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e48e0fa7f.html

- "Turks with African ancestors want their existence to be felt". Today's Zaman. Todayszaman.com. 11 May 2008. Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- "Afro-Türklerin tarihi, Radikal, 30 August 2008, retrieved 22 January 2009". Radikal.com.tr. 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- "Yugoslavia – Montenegro and Kosovo – The Next Conflict?".

- dBO Advertising Agency – dbo@cg.yu. "ULCINJ – HISTORY".

- Dieudonne Gnammankou, "African Slave Trade in Russia", in La Channe et le lien, Doudou Diene, (id.) Paris, Editions UNESCO, 1988.

- Saunders, Robert A. (2011). Ethnopolitics in Cyberspace: The Internet, Minority Nationalism, and the Web of Identity. Lanham: Lexington Books. p. 98. ISBN 9780739141946.

- Bernard Lewis. The Emergence of Modern Turkey. p. 82.

- Turkey: A Country Study, Federal Research Division, Kessinger Publishing, June 30, 2004 – 392 pages. Page 140 .

- http://www.christiansofiraq.com/caritaschaldeandec16.html Catholic Relief Agency Sheltering Iraqi Chaldean Refugees in Turkey

- http://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/11298 The Iraqi Refugee Crisis and Turkey: a Legal Outlook

- "Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response". data2.unhcr.org. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- Modern History of Armenia in the Works of Foreign Authors [Novaya istoriya Armenii v trudax sovremennix zarubezhnix avtorov], edited by R. Sahakyan, Yerevan, 1993, p. 15 (in Russian)

- Blundell, Roger Boar, Nigel (1991). Crooks, crime and corruption. New York: Dorset Press. p. 232. ISBN 9780880296151.

- Balakian, Peter (2009-10-13). The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America's Response. HarperCollins. p. 36. ISBN 9780061860171.

- Books, the editors of Time-Life (1989). The World in arms : timeframe AD 1900-1925 (U.S. ed.). Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Books. p. 84. ISBN 9780809464708.

- K. Al-Rawi, Ahmed (2012). Media Practice in Iraq. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 9. ISBN 9780230354524. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- history.com/books/Arm-pop-Ottoman-Emp.pdf THE POPULATION OF THE OTTOMAN ARMENIANS by Justin McCarthy

- Raymond H. Kevorkian and Paul B. Paboudjian, Les Arméniens dans l'Empire Ottoman à la vielle du génocide, Ed. ARHIS, Paris, 1992

- Bedrosyan, Raffi (August 1, 2011). "Bedrosyan: Searching for Lost Armenian Churches and Schools in Turkey". The Armenian Weekly. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "ONLY 200,000 ARMENIANS NOW LEFT IN TURKEY". New York Times. October 22, 1915. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- Turay, Anna. "Tarihte Ermeniler". Bolsohays: Istanbul Armenians. Retrieved 2007-01-04. External link in

|publisher=(help) - Hür, Ayşe (2008-08-31). "Türk Ermenisiz, Ermeni Türksüz olmaz!". Taraf (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2008-09-02. Retrieved 2008-09-02.

Sonunda nüfuslarını 70 bine indirmeyi başardık.

- "Turkey renames 'divisive' animals". BBC. 8 March 2005. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

Animal name changes: Red fox known as Vulpes Vulpes Kurdistanica becomes Vulpes Vulpes. Wild sheep called Ovis Armeniana becomes Ovis Orientalis Anatolicus Roe deer known as Capreolus Capreolus Armenus becomes Capreolus Cuprelus Capreolus.

- "Yiğidi öldürmek ama hakkını da vermek..." Lraper. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- "Patrik II. Mesrob Hazretleri 6 Agustos 2006 Pazar". Bolsohays News (in Turkish). August 7, 2006. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- Hovannisian, ed. by Richard G. (1991). The Armenian genocide in perspective (4. pr. ed.). New Brunswick, NJ [u.a.]: Transaction. ISBN 9780887386367.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Numbers of Australians Overseas in 2001 by Region – Southern Cross Group Archived 2008-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Human Rights Watch 1999 Report on Turkey

- Life of Azerbaijanis in Turkey Archived 2003-12-29 at the Wayback Machine. An interview with Sayyad Aran, Consul General of the Azerbaijan Republic to Istanbul. Azerbaijan Today

- (in Turkish) Qarslı bir azərbaycanlının ürək sözləri. Erol Özaydın

- (in Turkish) Iğdır Sevdası, Mücahit Özden Hun

- (in Turkish) KARS: AKP'nin kozu tarım desteği. Milliyet. 23 June 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2008

- Bernard Lewis. The Emergence of Modern Turkey. p. 87.

- http://www.todayszaman.com/news-313388-the-impact-of-bosnians-on-the-turkish-stateby-karol-kujawa-.html

- Brits Abroad: BBC

- Yavuz, Hande. "The Number Of Expats Has Reached 26,000". Capital. Archived from the original on 2011-01-14.

- The Balkans, Minorities and States in Conflict (1993), Minority Rights Publication, by Hugh Poulton, p. 111.

- Richard V. Weekes; Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey, Volume 1; 1984; p.612

- Raju G. C. Thomas; Yugoslavia unraveled: sovereignty, self-determination, intervention; 2003, p.105

- R. J. Crampton, Bulgaria, 2007, p.8

- Janusz Bugajski, Ethnic politics in Eastern Europe: a guide to nationality policies, organizations, and parties; 1995, p.237

- Gordon, Raymond G. Jr., ed. (2005). "Languages of Turkey (Europe)". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Fifteenth ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-159-6.

- "Trial sheds light on shades of Turkey". Hurriyet Daily News and Economic Review. 2008-06-10. Archived from the original on 2013-01-26. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- "Milliyet – Turkified Pomaks in Turkey" (in Turkish). www.milliyet.com.tr. Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- "Българската общност в Република Турция "

- News Review on South Asia and Indian Ocean. Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses. July 1982. p. 861.

- Problèmes politiques et sociaux. Documentation française. 1982. p. 15.

- Espace populations sociétés. Université des sciences et techniques de Lille, U.E.R. de géographie. 2006. p. 174.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911-1949. CUP Archive. pp. 236–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.

- Kazak Türkleri Vakfı Resmi Web Sayfası https://web.archive.org/web/20160913180046/http://www.kazakturklerivakfi.org/index.php?limitstart=118. Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Dru C. Gladney (1 April 2004). Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects. University of Chicago Press. pp. 184–. ISBN 978-0-226-29776-7.

- Kazak Kültür Derneği http://www.kazakkultur.org/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Lonely Planet (1 June 2014). Great Adventures. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 978-1-74360-102-0.

- Finkel, Michael (February 2013). "Wakhan Corridor". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- David J. Phillips (2001). Peoples on the Move: Introducing the Nomads of the World. William Carey Library. pp. 314–. ISBN 978-0-87808-352-7.

- Кыргызстан Достук жана Маданият Коому (Kırgızistan Kültür ve Dostluk Derneği Resmi Sitesi) https://web.archive.org/web/20131008052336/http://www.kyrgyzstan.org.tr/tr.html. Archived from the original on 2013-10-08. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Kahl, Thede (2006). "The Islamisation of the Meglen Vlachs (Megleno-Romanians): The Village of Nânti (Nótia) and the "Nântinets" in Present-Day Turkey". Nationalities Papers. 34 (1). pp. 71–90. doi:10.1080/00905990500504871.

- Evrenpaşa Köyü | Güney Türkistan'dan Anadoluya Urfa Ceylanpınar Özbek Türkleri Archived 2019-06-23 at the Wayback Machine. Evrenpasakoyu.wordpress.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- Balcı, Bayram (Winter 2004). "The Role of the Pilgrimage in Relations between Uzbekistan and the Uzbek Community of Saudi Arabia" (PDF). Central Eurasian Studies Review. 3 (1): 17. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- "ISIL recruits Chinese with fake Turkish passports from Istanbul". BGNNews.com. Istanbul. April 9, 2015. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

- Blanchard, Ben (July 11, 2015). "China says Uighurs being sold as 'cannon fodder' for extremist groups". Reuters. BEIJING.

- "Uyghurs sold as 'cannon fodder' for extremist groups: China". Asia Times. July 11, 2015. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016.

- Yitzhak Shichor; East-West Center (2009). Ethno-diplomacy, the Uyghur hitch in Sino-Turkish relations. East-West Center. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-932728-80-4.

- Barbara Pusch; Tomas Wilkoszewski (2008). Facetten internationaler Migration in die Türkei: gesellschaftliche Rahmenbedingungen und persönliche Lebenswelten. Ergon-Verlag. p. 221. ISBN 978-3-89913-647-0.

- Dru C. Gladney (1 April 2004). Dislocating China: Muslims, Minorities, and Other Subaltern Subjects. University of Chicago Press. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-0-226-29776-7.

- Touraj Atabaki; John O'Kane (15 October 1998). Post-Soviet Central Asia. I. B. Tauris. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-86064-327-9.

- S. Frederick Starr (4 March 2015). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. Routledge. pp. 391–. ISBN 978-1-317-45137-2.

- J. Craig Jenkins; Esther E. Gottlieb (31 December 2011). Identity Conflicts: Can Violence be Regulated?. Transaction Publishers. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-1-4128-0924-5.

- Exploring the Nature of Uighur Nationalism: Freedom Fighters Or Terrorists? : Hearing Before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights, and Oversight of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session, June 16, 2009. U.S. Government Printing Office. 2009. p. 52.

- United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights, and Oversight (2009). Exploring the nature of Uighur nationalism: freedom fighters or terrorists? : hearing before the Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights, and Oversight of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, One Hundred Eleventh Congress, first session, June 16, 2009. U.S. G.P.O. p. 52. ISBN 9780160843945.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Uygur Ajan Rabia Kadir, Doğu Türkistanlı Mücahidleri İhbar Etti". ISLAH HABER "Özgür Ümmetin Habercisi". 8 January 2015.

- Zenn, Jacob (10 October 2014). "An Overview of Chinese Fighters and Anti-Chinese Militant Groups in Syria and Iraq". China Brief. The Jamestown Foundation. 14 (19). Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- YoSIN, Muhammad (2015-11-01). "Истанбулда Туркистонлик муҳожирларга қилинаётган қотилликларга қарши норозилик намойиши бўлди (Kирил ва Лотинда)". Uluslararası Türkistanlılar Dayanışma Derneği.

- "China entered into Istanbul,Turkey with her 150 Spies". EAST TURKESTAN BULLETIN NEWS AGENT/ News Center. 29 November 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016.

- "Çin İstihbaratı, 150 Ajan İle İstanbul'a Giriş Yaptı". DOĞU TÜRKİSTAN BÜLTENİ HABER AJANSI / Haber Merkezi. 20 November 2015. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015.

- DOĞU TÜRKİSTAN GÖÇMENLER DERNEĞİ http://www.doguturkistan.com.tr/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Doğu Türkistan Kültür ve Dayanışma Derneği Genel Merkezi http://www.gokbayrak.com/#. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Doğu Türkistan Maarif ve Dayanışma Derneği http://maarip.org/tr/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Bernard Lewis. The Emergence of Modern Turkey. p. 94.

- "Ethnologue: Abasinen". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- "Ethnologue: Abchasen". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- Papşu, Murat (2003). Çerkes dillerine genel bir bakış Kafkasya ve Türkiye Archived 10 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Nart Dergisi, Mart-Nisan 2003, Sayı:35

- Адыгэхэм я щыгъуэ-щIэж махуэм къызэрагъэпэща пэкIур Тыркум гулъытэншэу къыщагъэнакъым. 2012-06-09 (Çerkesçe)

- "Kafkas Dernekleri Federasyonu İlkeleri". Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Peter Alford Andrews, Rüdiger Benninghaus,Ethnic groups in the Republic of Turkey, Vol. 2, Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 1989, Wiesbaden, ISBN 3-88226-418-7, p. 87., Peter Alford Andrews, Türkiye'de Etnik Gruplar, ANT Yayınları, Aralık 1992, ISBN 975-7350-03-6, s.116–118.

- Crimean Tatars and Noghais in Turkey

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2012-08-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "No Filipino casualty in Turkey quake – DFA". GMA News. 3 August 2010.

- "PGMA off on a 3-nation swing". Pinoy Global Online News. 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2018-12-15.

- Şentürk, Cem (2007-10-15). "The Germans in Turkey". Turkofamerica. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- European Commission for Democracy through Law (2002). The Protection of National Minorities by Their Kin-State. Council of Europe. p. 142. ISBN 978-92-871-5082-0. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

In Turkey the Orthodox minority who remained in Istanbul, Imvros and Tenedos governed by the same provisions of the treaty of Lausanne was gradually shrunk from more than 200,000 in 1930 to less than 3,000 today.

- http://www.demography-lab.prd.uth.gr/DDAoG/article/cont/ergasies/tsilenis.htm

- Kilic, Ecevit (2008-09-07). "Sermaye nasıl el değiştirdi?". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-12-25.

6–7 Eylül olaylarından önce İstanbul'da 135 bin Rum yaşıyordu. Sonrasında bu sayı 70 bine düştü. 1978'e gelindiğinde bu rakam 7 bindi.

- "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 2008-12-15. Archived from the original on 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- Lois Whitman Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity: The Greeks of Turkey. Human Rights Watch, September 1, 1992 – 54 pages. Page 2

- Turkey: Istanbul’s Greek Community Experiencing a Revival (Eurasianet, 2 March 2011)

- Jobseekers from Greece try chances in Istanbul (Hurriyet Daily News, 9 January 2012)

- Hunter, Shireen (2010). Iran's Foreign Policy in the Post-Soviet Era: Resisting the New International Order. ABC-CLIO. p. 160. ISBN 9780313381942.

- "Kürt Meselesi̇ni̇ Yeni̇den Düşünmek" (PDF). KONDA. July 2010. pp. 19–20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2013-06-11.

- David McDowall. A Modern History of the Kurds. Third Edition. I.B.Tauris, May 14, 2004 – 504 pages, page 3.

- "Kurdistan-Turkey". GlobalSecurity.org. 2007-03-22. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

- The Uses and Abuses of History, Margaret MacMillan Google Books

- Mersin'in bahanesi yok Archived 2012-10-19 at the Wayback Machine, Radikal, 26 May 2007

- BİZİM AHISKA DERGİSİ WEB SAYFASI http://www.ahiska.org.tr/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Türkiye’deki Çingene nüfusu tam bilinmiyor.Article from Hürryet

- Romani, according to latest estimations of some experts, number between 4 and 5 million. European Roma Information Office

- "Bu düzenlemeyle ortaya çıkan tabloda Türkiye’de yetişkinlerin (18 yaş ve üstündekilerin) etnik kimliklerin dağılımı ... % 0,05 Roman ... şeklindedir.": "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-30. Retrieved 2009-02-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Elena Marushiakova, Veselin Popov (2001) "Gypsies in the Ottoman Empire", ISBN 1902806026University of Hertfordshire Press

- Original: Елена Марушиакова, Веселин Попов (2000) "Циганите в Османската империя". Литавра, София (Litavra Publishers, Sofia).(in Bulgarian)

- «Получить точные статистические данные относительно численности соотечественников в Турции не представляется возможным… в целом сегодня можно говорить примерно о 50 тыс. проживающих в Турции россиян». // Интервью журналу «Консул» № 4 /19/, декабрь 2009 года на сайте МИД РФ

- Demographics of Turkey#1965 census

- Tahta, Selahattin 2002: Ursprung und Entwicklung der Zaza-Nationalbewegung im Lichte ihrer politischen und literarischen Veröffentlichungen. Unpublished Master Thesis. Berlin.

- Zaza people and Zaza language

- Kird, Kirmanc Dimili or Zaza Kurds, Deng Publishing, Istanbul, 1996 by Malmisanij

- ıdır EREN, “Dil İle İnsan Sferi Arasındaki İlişki

- Andrews, Peter Alford 1989: Ethnic Groups in the Republic of Turkey. Wiesbaden

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2015-11-14.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://tr.euronews.com/2019/01/03/konda-nin-toplumsal-degisim-raporuna-gore-turkiye-de-inancsizlik-yukseliste

- International Religious Freedom Report 2008-Turkey

- Khojoyan, Sara (16 October 2009). "Armenian in Istanbul: Diaspora in Turkey welcomes the setting of relations and waits more steps from both countries". ArmeniaNow.com. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- The Greeks of Turkey, 1992–1995 Fact-sheet Archived 2011-08-30 at the Wayback Machine by Marios D. Dikaiakos

- Christen in der islamischen Welt – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ 26/2008)

- "Priest's killing shocks Christians in Turkey". Catholic World News. February 6, 2006. Archived from the original on February 11, 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-26.

- "Priest Slain in Turkey Had Sought Pope Visit". Reuters. February 9, 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-26.

- "Confirmed: Pope to visit Turkey in November". Catholic World News. February 9, 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-26.

- Donovan, Jeffrey (April 20, 2005). "World: New Pope Seen As Maintaining Roman Catholic Doctrinal Continuity". Radio Free Europe. Retrieved 2006-06-26.

- "Turkey". International Religious Freedom Report 2004. September 15, 2004. Retrieved 2006-06-26.

- "World Evangelical Alliance". Archived from the original on 2013-12-03.

- "German Site on Christians in Turkey". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28.

- "Christian Persecution Info".

- "Christianity Today".

- Turkish Protestants still face "long path" to religious freedom

- Christians in eastern Turkey worried despite church opening

- Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks

- TURKEY: Protestant church closed down

- State and rural society in medieval Islam: sultans, muqtaʻs, and fallahun. Leiden: E.J. Brill. 1997. p. 162. ISBN 90-04-10649-9.

- Structure and Function in Turkish Society. Isis Press, 2006, p. 81).

- "The Alevi of Anatolia", 1995.

- minorityrights.org, Caferis

- Issa, Chaukeddin (2008). Das Yezidentum : Religion und Leben, p.180. Oldenburg: Dengê Êzîdiyan. ISBN 978-3-9810751-4-4.

- Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker: Yezidi. 1989