St. Louis Lambert International Airport

St. Louis Lambert International Airport (IATA: STL, ICAO: KSTL, FAA LID: STL), formerly Lambert–St. Louis International Airport, is an international airport serving St. Louis, Missouri, United States. Commonly referred to as Lambert Field or simply Lambert, it is the largest and busiest airport in Missouri. The 2,800-acre (1,133 ha)[2] airport sits 14 miles (23 km) northwest of downtown St. Louis in unincorporated St. Louis County between Berkeley and Bridgeton. In January 2019, it saw more than 259 daily departures to 78 nonstop domestic and international locations.[3]

St. Louis Lambert International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | City of St. Louis | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | St. Louis City Airport Commission | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | St. Louis, Missouri and Greater St. Louis | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Unincorporated St. Louis County 10 miles (16 km) NW of St. Louis | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 605 ft / 184.4 m | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 38°44′50″N 090°21′41″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||||||

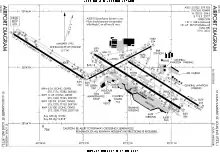

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||||||

STL Location of airport in Missouri  STL STL (the United States) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2020) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Source: St. Louis Lambert International Airport[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Named for Albert Bond Lambert, an Olympic medalist and prominent St. Louis aviator, the airport rose to international prominence in the 20th century thanks to its association with Charles Lindbergh, its groundbreaking air traffic control, its status as the primary hub of Trans World Airlines, and its iconic terminal.[4] St. Louis Lambert International Airport is the primary airport in the St. Louis area, with MidAmerica St. Louis Airport, about 37 miles (59 km) east, serving as a secondary metropolitan commercial airport. The two airport terminals are connected by the Red Line of the city's light rail mass transit system, the MetroLink.

History

Beginnings

The airport originated as a balloon launching base called Kinloch Field, part of the 1890s Kinloch Park suburban development. The Wright brothers and their Exhibition Team visited the field while touring with their aircraft. During a visit to St. Louis, Theodore Roosevelt flew with pilot Arch Hoxsey on October 11, 1910, becoming the first U.S. president to fly. Later, Kinloch hosted the first experimental parachute jump.[5]

In June 1920, the Aero Club of St. Louis leased 170 acres of cornfield, the defunct Kinloch Racing Track[6] and the Kinloch Airfield in October 1923, during The International Air Races. The field was officially dedicated as Lambert–St. Louis Flying Field[7] in honor of Albert Bond Lambert, an Olympic silver medalist golfer in the 1904 Summer Games, president of Lambert Pharmaceutical Corporation (which made Listerine),[8] and the first person to receive a pilot's license in St. Louis. In February 1925, "Major" (his 'rank' was given by the Aero Club and not the military) Lambert bought the field and added hangars and a passenger terminal. Charles Lindbergh's first piloting job was flying airmail for Robertson Aircraft Corporation from Lambert Field; he left the airport for New York about a week before his record-breaking flight to Paris in 1927. In February 1928, the City of St. Louis leased the airport for $1. Later that year, Lambert sold the airport to the City after a $2 million bond issue was passed, making it one of the first municipally-owned airport in the United States.[4][9]

In the late 1920s, Lambert Field became the first airport with an air traffic control system–albeit one that communicated with pilots via waving flags. The first controller was Archie League.[10]

In 1925, the airport became home to Naval Air Station St. Louis, a Naval Air Reserve facility that became an active-duty installation during World War II.

In 1930, the airport was officially christened Lambert–St. Louis Municipal Airport by Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd. The first terminal building opened in 1933.[9]

By the 1930s, Robertson Air Lines, Marquette Airlines and Eastern Air Lines provided passenger service to St. Louis, as did Transcontinental & Western Air (later renamed Trans World Airlines).[9][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

In August 1942, voters passed a $4.5 million bond issue to expand the airport by 867 acres and build a new terminal.[9]

During World War II, the airport became a manufacturing base for the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation and Curtiss-Wright.[19][20]

1945–1982: Post World War II expansion; Ozark Airlines hub

After the war, NAS St. Louis reverted to a reserve installation, supporting carrier-based fighters and land-based patrol aircraft. When it closed in 1958, most of its facilities were acquired by the Missouri Air National Guard and became Lambert Field Air National Guard Base. Some other facilities were retained by non-flying activities of the Naval Reserve and Marine Corps Reserve, while the rest was redeveloped to expand airline operations at the airport.

Ozark Air Lines began operations at the airport in 1950.[9]

To handle increasing passenger traffic, Minoru Yamasaki was commissioned to design a new terminal, which began construction in 1953. Completed in 1956 at a total cost of $7.2 million, the three-domed design preceded terminals at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York City and Paris–Charles de Gaulle Airport.[4][9] A fourth dome was added in 1965 following the passage of a $200 million airport revenue bond.[21][22][9]

The April 1957 Official Airline Guide shows 44 weekday TWA departures; American, 24; Delta, 16; Ozark, 14; Eastern, 13; Braniff, 6 and Central, 2. The first scheduled jet was a TWA 707 to New York on July 21, 1959.[23][24]

In 1971 the airport became Lambert–St. Louis International Airport.[20]

In the 1970s St. Louis city officials proposed a new airport in suburban Illinois to replace Lambert. After Missouri residents objected in 1977, Lambert received a $290-million expansion that lengthened the runways, increased the number of gates to 81, and boosted its capacity by 50 percent (a proposed Illinois airport was later built, though not near the originally intended site; MidAmerica St. Louis Airport opened in 1997 in Mascoutah, Illinois). Concourse A and Concourse C were rebuilt into bi-level structures with jet bridges as part of a $25 million project in the mid-1970s designed by Sverdrup. The other concourses were demolished. Construction began in the spring of 1976 and was completed in September 1977.[25] A $20 million, 120,000-square-foot (11,000 m2) extension of Concourse C for TWA and a $46 million, 210,000-square-foot (20,000 m2) Concourse D for Ozark Airlines (also designed by Sverdrup) were completed in December 1982.[26][27]

Ozark Airlines established its only hub at Lambert in the late 1950s. The airline grew rapidly, going from 36 million revenue passenger miles in 1955, to 229 million revenue passenger miles in 1965. The jet age came to Ozark in 1966 with the Douglas DC-9-10 and its network expanded to Denver, Indianapolis, Louisville, Washington, D.C., New York City, Miami, Tampa and Orlando. With the addition of jets, Ozark began its fastest period of growth, jumping to 653 million revenue passenger miles in 1970 and 936 million revenue passenger miles in 1975;[28] Ozark soon faced heavy competition in TWA's new hub at Lambert.

In 1979, the year after airline deregulation, STL's dominant carriers were TWA (36 routes) and Ozark (25), followed by American (17) and Eastern (12). Other carriers at STL included Air Illinois, Air Indiana, Braniff International Airways, Britt Airways, Brower Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Frontier Airlines, Northwest Orient, Republic Airlines, Texas International Airlines, Trans-Mo Airlines and USAir.[29]

1982–2001: Trans World Airlines hub

_JP5893659.jpg.webp)

After airline deregulation in 1978, airlines began to realign their operations around a hub and spoke model. Trans World Airlines (TWA) was headquartered in New York City but its main base of employment was at Kansas City International Airport and had large operations at Chicago O'Hare International Airport as well as St. Louis. TWA deemed Kansas City's terminals as unsuitable to serve as a primary hub. TWA reluctantly ruled out Chicago, as its Chicago operation was already losing $25 million a year under competition from American Airlines and United Airlines. This meant that St. Louis was the carrier's only viable option. TWA proceeded to downsize Chicago and build up St. Louis, swapping three Chicago gates for five of American's St. Louis gates. By December 1982, St. Louis accounted for 20% of TWA's domestic capacity. Lambert's terminal was initially too small for this operation, and TWA was forced to use temporary terminals, mobile lounges and airstairs to handle the additional flights.[30] After Concourse D was completed in 1985, TWA began transatlantic service from Lambert to London, Frankfurt and Paris.[31]

TWA's hub grew again in 1986 when the airline bought Ozark Airlines, which operated its hub from Lambert's B, C, and D concourses. In 1985, TWA had accounted for 56.6% of boardings at STL while Ozark accounted for 26.3%, so the merged carriers controlled over 80% of the traffic.[32] As of 1986, TWA served STL with nonstop service to 84 cities, an increase from 80 cities served by TWA and/or Ozark in 1985, before the merger.

Despite the entry of Southwest Airlines in the market in 1985, the TWA buyout of Ozark and subsequent increase in the nonstop cities served, the number of passengers using Lambert held steady from 1985 through 1993, ranging between 19 million and 21 million passengers per year throughout the period.

Lambert again grew in importance for TWA after the airline declared bankruptcy in 1992 and moved its headquarters to St. Louis from Mount Kisco, NY in 1993.[33] TWA increased the number of cities served and started routing more connecting passengers through its hub at Lambert: the total number of passengers using Lambert rose from 19.9 million passengers enplaned in 1993 to 23.4 million in 1994, jumping almost 20% in one year. Growth continued, with total enplaned passengers jumping to 27.3 million by 1997 and 30.6 million in 2000, the highest level in its history.[34]

By the late 1990s, Lambert was TWA's dominant hub, with 515 daily flights to 104 cities as of September 1999. Of those 515 flights, 352 were on TWA mainline aircraft and 163 were Trans World Express flights operated by its commuter airline partners. During this period, Lambert Field was ranked as the eighth-busiest U.S. airport by flights (not by total passengers), largely due to TWA's hub operations, Southwest Airlines' growing traffic, and commuter traffic to smaller cities in the region. Congestion caused delays during peak hours and was exacerbated when bad weather reduced the number of usable runways from three to one. To cope, Lambert officials briefly redesignated the taxiway immediately north of runway 12L–30R as runway 13–31 and used it for commuter and general aviation traffic. Traffic projections made in the 1980s and 1990s predicted yet more growth, however: enough to strain the airport and the national air traffic system.[35]

These factors led to the planning and construction of a 9,000-foot runway, dubbed Runway 11/29, parallel to the two larger existing runways. At $1.1 billion, it was the costliest public works program in St. Louis history.[36] It required moving seven major roads and destroying about 2,000 homes, six churches, and four schools in Bridgeton.[36][37][38] Work began in 1998 and continued even as traffic at the airport declined after the 9/11 attacks, the collapse of TWA and its subsequent purchase by American, and American's flight reductions several years later.[39][40] As of 2018, the runway is used for approximately 12% of all takeoffs and landings.[41]

2001–2009: American Airlines hub; closure of Air National Guard base

.jpg.webp)

As TWA entered the new millennium, its financial condition proved too precarious to continue alone and in January 2001, American Airlines announced it was buying TWA, which was completed in April of that year.[42] The last day of operations for TWA was December 1, 2001, including a ceremonial last flight to TWA's original and historic hometown of Kansas City before returning to St. Louis one final time. The following day, TWA was officially absorbed into American Airlines.[43][44] The plan for Lambert was to become a reliever hub for the existing American hubs at Chicago–O'Hare and Dallas/Fort Worth. American was looking at something strategic with its new St. Louis hub to potentially offload some of the pressure on O'Hare as well as provide a significant boost to the airline's east/west connectivity.[45][46]

The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks were a huge demand shock to air service nationwide, with total airline industry domestic revenue passenger miles dropping 20% in October 2001 and 17% in November 2001.[47] Overnight, American no longer had the same need for a hub that bypassed its hubs at Chicago and Dallas, which suddenly became less congested.[48] As a result of this and the ongoing economic recession, service at Lambert was subsequently reduced over the course of the next few years; to 207 flights by November 2003.[49][50][51] Total passenger traffic dropped to 20.4 million that same year.[34] On the international front, flights to Paris went to seasonal in December 2001 and transatlantic service was soon discontinued altogether when American dropped flights to London in late 2003.[52][53]

In 2006, the United States Air Force announced plans to turn the 131st Fighter Wing of the Missouri Air National Guard into the 131st Bomb Wing. The wing's 20 F-15C and F-15D aircraft were moved to the Montana Air National Guard's 120th Airlift Wing at Great Falls International Airport/Air National Guard Base, Montana and the Hawaii Air National Guard's 154th Wing at Hickam AFB, Hawaii. The pilots and maintainers moved to Whiteman AFB, Missouri to fly and maintain the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber as the first Air National Guard wing to fly the aircraft. Lambert Field Air National Guard Base formally shut down on June 13, 2009 when the final two F-15C Eagles did a low approach over the field and then flew away, ending an 86-year chapter of Lambert's history.[54][55]

2006 also saw the completion of the W-1W airport expansion after 8 years of work. The culmination of this program was the opening of Runway 11/29, the airport's fourth, on April 13, 2006 when American Airlines Flight 2470 became the first commercial airliner to land on the new runway.[56][40]

In 2007, airport officials announced the largest renovation in the airport's history: a $70 million effort to overhaul Terminal 1 called "The Airport Experience Project." Planned renovations included updating and modernizing the interior, redesigning signage, and modernizing the baggage system. The first phase of the project began in 2008, with the replacement of signage in order to improve navigation inside the terminal, replacement of the baggage handling system, and renovation of the domed vaults of the ticketing hall. Bonds were issued in 2009 to assist with funding.[57]

In 2008, Lambert's position as an American Airlines hub faced further pressure due to increased fuel costs and softened demand because of a depressed economy. American cut its overall system capacity by over 5% during 2008.[58] At Lambert, American shifted more flights from mainline to regional.[59] Total passengers enplaned fell 6% to 14.4 million in 2008, then fell another 11% to 12.8 million passengers in 2009.[34]

In September 2009, American Airlines announced that as a part of the airline's restructuring, it would eliminate its St. Louis hub by reducing its operations from approximately 200 daily flights to 36 daily flights to nine destinations in the summer of 2010.[60] These cuts ended the remaining hub operation.[61] American's closure of the St. Louis hub coincided with its new "Cornerstone" plan, wherein the airline would concentrate itself in several major markets: Chicago, Dallas/Fort Worth, Miami, New York, and Los Angeles.[62][63]

2009–2017: Southwest expansion; rebirth of the airport

In early October 2009, Southwest Airlines announced the addition of six daily flights to several cities as an immediate response to the cutbacks announced by American Airlines. Then on October 21, 2009, Southwest announced that it would increase service with a "major expansion" in St. Louis by May 2010. The airline announced it would begin flying nonstop from St. Louis to 6 new cities for a new total of 31 destinations, increasing the number of daily departures from 74 to 83. This had the effect of replacing American as the carrier with the most daily flights after American's service cuts in summer 2010.[64][65]

The airport hit its nadir in 2010 following the closure of the American hub in the midst of the Great Recession, ending the year with the lowest passenger and aircraft movement statistics of any modern year on record. Fortunately for the airport, Southwest's announced expansion at Lambert immediately began to fill in for many of the holes left by the demise of the hub. What followed were several years of steady growth by Southwest that maintained passenger numbers at a fairly steady level, allowing airport leadership time to shift priorities and begin the long road to recovery in earnest.

Complicating recovery was the 'Good Friday tornado'. At about 8:10 p.m. on April 22, 2011, an EF4[66] tornado struck the airport's Terminal 1, destroying jetways and breaking more than half of the windows.[67][68][69] One Southwest Airlines aircraft was damaged when the wind pushed a baggage conveyor belt into it. Four American Airlines aircraft were damaged, including one that was buffeted by 80 mph crosswinds while taxiing after landing.[70] Another aircraft, with passengers still on board, was moved away from its jetway by the storm.[71] The FAA closed the airport at 08:54 pm CDT, then reopened it the following day at temporarily lower capacity.[72] The damage to Concourse C even forced several airlines to use vacant gates in the B and D concourses.[73] The TSA would later declare Lambert Airport its "Airport of the Year" for "exceptional courtesy [and] high-quality security" as well as the "excellent response by airport officials during and after the tornado".[74] In the meantime, the tornado and subsequent damage to the terminal facilities accelerated the timeline for the "Airport Experience Program", a large-scale renovation of the interior spaces of Terminal 1 and its concourses.[75] Concourse C underwent renovations and repairs and finally reopened on April 2, 2012.[73]

One of the first true indications of the airport's recovery was in May 2013, when several credit agencies improved their evaluations of the airport's finances. Moody's raised its rating on Lambert Airport's bonds to A3 with a stable outlook from Baa1 with a stable outlook. Standard & Poor's (S&P) raised its rating to A- with a stable outlook from A- with a negative outlook. This was the first time in more than a decade that both Moody's and Standard & Poor's ratings for the Airport had both been in the single "A" category. Earlier in the month, Fitch Ratings upgraded outstanding airport revenue bonds to 'BBB+' from 'BBB' with a stable outlook. The rating agencies attributed the upgrades to strong fiscal management and positive passenger traffic.[76]

In 2015, the airport released a new Five Year Strategic Plan. The overall mission statement of the airport was given as "connecting [the St. Louis] region with the world", while also detailed were four major strategic objectives: Strengthening Financial Sustainability; Sustaining and Growing Passenger Air Service; Creating a Positive and Lasting Impression for the Region; and Generating Economic Development. The plan went into detail regarding each objective, listing overall measures of success and potential methods to attain successful outcomes. Some of the given measures of success are reducing costs per enplaned passenger, reducing the airport's debt service, maximizing sources of revenue (primarily non-aviation), increasing passenger throughput, gaining new passenger services, improving satisfaction survey scores, and increasing revenue from cargo.[77]

In January 2016, the airport completed renovations of Terminal 1, concluding more than seven years of planning and renovation work throughout the airport.[57]

In late 2016, the City of St. Louis announced it would either keep the name Lambert–St. Louis International Airport or change it to St. Louis International Airport at Lambert Field. This effort to re-brand was brought about to further freshen up the airport's image and also to emphasize the importance of 'St. Louis' in the name, as research carried out at the behest of the city government had found that the current name had the potential to confuse travelers.[78]

The decision was not without controversy, however: descendants of Albert Bond Lambert opposed moving 'Lambert' to the end of the name as they argued it de-emphasized the importance of Maj. Lambert to both the airport's history and the history of aviation in general. Thus, the proposal was amended, and the St. Louis Airport Commission voted unanimously to change the name of the airport to St. Louis Lambert International Airport on September 7, 2016.[79][80] The proposal thereafter gained the approval of the city's Board of Estimate and Apportionment. On October 14, 2016, the St. Louis Board of Aldermen approved the name change, and on October 25, St. Louis mayor Francis Slay signed the bill approving the name change.[81] After going through the formal process to submit the name change to the Federal Aviation Administration, the airport debuted new branding and a completely redesigned website on February 14, 2017, signaling the start of a new era in the airport's history.[82]

2017–present: Continued growth

In early 2017, Lambert began to renovate four unused gates in Concourse D and renamed them as E gates. This work was undertaken to accommodate the continued growth of Southwest Airlines at Lambert's Terminal 2 and was finished in time for the summer flying season.[83][84]

In May 2017, Moody's again raised its rating of Lambert's bonds and debt to A3 with a positive outlook from A3 with a stable outlook, primarily due to continued growth in enplanements, declining debt, and no major capital expenditures. By the same token, S&P issued an A- long-term rating with a positive outlook, up from A- with a stable outlook, citing "favorably declining debt levels and strong liquidity [as well as] stable passenger enplanement levels and a good competitive position that supports a good base of air travel demand".[85] Later in the year, Fitch also raised its bond outlook to A- with a stable outlook from BBB+ with a positive outlook, citing many of the same reasons as the other two agencies.[86]

An August 21, 2017 FAA Press Release announced that Lambert was one of 67 airports selected to receive infrastructure grants from the U.S. DOT. The airport was granted $7.1 million for "Realignment and Reconstruction of Taxiway Kilo; Reconstruction of Taxiway Sierra from Taxiway Echo to Runway 12R-30L; Widening of Taxiway Kilo Fillet from Runway 12R-30L to Taxiway Delta; and Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of Runway 12L-30R Outer Panels and Replacement of Electrical Circuits".[87]

On August 23, 2017, WOW air announced that in 2018 it would commence four weekly A321 flights between St. Louis and Reykjavík, Iceland as part of a planned multi-city U.S. expansion. As part of the service agreement, the Airport and St. Louis County Port Authority combined for approximately $800,000 in incentives to market the route and waived landing fees for WOW air for 18 months, while WOW air guaranteed its services on the route would operate for at least two years.[88] Due to strong sales, WOW added a fifth weekly flight in January 2018.[89] The first flight from Reykjavík landed on May 17, 2018, becoming the first regularly scheduled commercial flight between St. Louis and any part of Europe since American Airlines discontinued European service in 2003.[90] However, just five months later on October 15, WOW air announced that it would be ending the route, with the last flight planned on January 7, 2019. The announcement blindsided airport officials, who had been told that St. Louis was one of the airline's top-performing Midwestern markets not long before the cancellation and were under the impression that the airline was satisfied with the route's performance. As it turned out, St. Louis was just the first of several announced cancellations of new U.S. destinations by WOW, possibly due to ongoing financial difficulties at the burgeoning airline. Due to the cancellation, WOW did not meet the criteria to receive any of the offered marketing incentives, though it is unclear whether or not the airline would have to repay the waived landing fees.[91][92]

On October 30, 2017, American Airlines announced that it would close its St. Louis pilot base in September 2018, affecting 153 pilots and several administrative staff. American cited the retirement of older aircraft and network planning as the primary reasons for the shutdown. The move was not expected to affect services to the airport, but signaled the end of one of the final remnants of TWA's legacy at Lambert.[93][94][95]

In March 2018, the airport announced that STL Fuel Company LLC, the consortium that manages fuel services at the airport, had been cleared to construct a new $50 million fuel storage facility on the northeastern part of the airport property. The new facility will have three 722,000 gallon storage tanks initially, though there will be room for expansion. The current facility, located across from Terminal 1, was one of the first below-ground integrated aircraft fueling hydrant systems in the country when it began operations in 1957; its age and new environmental regulations are the catalyst for the move. Once the new facility is complete, the current facility will be demolished and the environmental conditions around it remediated at the consortium's expense. Preliminary work, including upgrades to the existing terminal fuel lines, was completed by August 2019, with site preparation and foundation work on the storage facility proper beginning that same month.[96][97]

In June 2018, the airport announced the commencement of service by a new airline, Sun Country Airlines, with seasonal flights to Fort Myers and Tampa beginning later in 2018.[98] On January 8, 2019, Sun Country announced an expansion of services from Lambert, including two new destinations — Portland and Minneapolis, both slated to begin on June 7, 2019.[99]

On July 16, 2018, the United States Department of Transportation announced an additional grant of $10.2 million for Lambert as part of the "Airport Improvement Program" in order to facilitate repairs to runway 12L/30R and "associated airfield guidance signs and runway lighting".[100]

A Transportation Security Administration press release on July 30, 2018 indicated that Lambert would be one of the first 15 airports in the country to receive one of its new 'computed tomography scanners' for testing purposes. This technology creates fully three-dimensional scans of items and enhances explosive-detecting methodology, and has to potential to significantly speed up the security screening process. The equipment was installed by the end of 2018.[101]

In August 2018, Moody's raised its rating of Lambert's bonds yet again, this time from A3 with a positive outlook to A2 with a stable outlook. The company stated that the airport's debt service "will improve incrementally over the near term with STL’s declining cost structure and positive enplanement trend driving increasingly competitive cost per enplanement (CPE)" and also cited "rapid growth in connecting enplanements, new routes and increased flight frequencies and growth in passenger seats to the market" as further factors leading to the upgrade.[102] Following Moody's announcement, S&P affirmed the airport's bond rating as A- with a stable outlook. In October 2018, Fitch also upgraded its rating of the airport's bonds, this time to A- with a positive outlook, up from stable. Fitch stated that the upgrade "reflects an expanding enplanement base, stable cash flow, and declining leverage at STL."[103]

On August 31, 2018, the City of St. Louis issued an RFQ for "Terminal 2 Baggage Carousel Expansion".[104] With a total estimated cost of $23.3 million, of which $16.2 million would be paid for by Southwest, the project aims to add a 10,500 square-foot addition to the Terminal 2 structure, add a third baggage carousel, replace the existing baggage carousels, and provide for the replacement or addition of all needed building utilities, signage, and systems, including luggage belts and a new bag transfer facility.[105][106][107] Also being considered is a move of the current curbside baggage check-in location from the north end to the south end of the departure drop-off area. The project is awaiting approval from the city's Board of Aldermen and Board of Estimate and Apportionment.[108]

In June 2019, Moody's reaffirmed the airport's bond rating as A2 with a stable outlook, citing much of the same rationale as with its 2018 assessment.[109] At the same time, the airport issued a press release stating that S&P had raised its rating of the airport's long-term bonds to 'A' from 'A-', citing that the airport has "strong origin and destination demand, an extremely strong economic profile in [its] service area, and 'a very strong management team that has sufficiently managed risks to ensure the airport’s steady financial and operational performance'".[110] Later in the year, Fitch also improved its rating of Lambert's debt, raising from A- to A. Fitch cited rising traffic levels and "sustained robust financial metrics", in addition to declining leverage and moderating airline costs as the reasons for the upgrade.[111]

On July 31, 2019, it was announced that Lambert would receive $5.29 million in infrastructure grants as part of $478 million in airport infrastructure grants awarded by the FAA. The money will be used for taxiway rehabilitation projects.[112]

As of August 2019, Southwest Airlines is the dominant carrier at Lambert, accounting for nearly 62% of passengers over the previous 12-month time period. American Airlines is a solid second, at just over 10.4%, while Delta Air Lines is third at 7.2%.[113] St. Louis International is one of Southwest Airlines "Gateway" hub airports connecting international service to customers.

An ongoing dispute is a potential privatization of the airport. This initiative was started in 2017 by St. Louis mayor Francis Slay shortly before leaving office. Slay traveled to Washington, D.C. in March of that year to submit a preliminary application with the FAA to explore privatization, with the hope that Lambert would be selected for one of five open slots in the FAA's "Airport Privatization Pilot Program". The primary reason cited for the effort is for extra capital to be funneled into the city's coffers as part of a lease with a private airport operator, as the current arrangement provides approximately $6 million in revenue annually to the city and limits what that money may be spent on.[114] On April 24, 2017, the FAA accepted the preliminary application, allowing the city to fully explore the possibility of privatizing the airport.[115] In December 2019, Mayor Lyda Krewson announced the end of any privitization efforts.

Facilities

Airfield

The airport has four runways, three of which are parallel with one crosswind. The crosswind runway, 6/24, is the shortest of the four at 7,607 feet (2,319 m). The newest runway is 11/29, completed in 2006 as part of a large expansion program.[2][116]

The airport's current ~156-foot (~47.6-meter) control tower opened in 1997 at a cost of approximately $15 million.[117][118]

Terminals

The airport has two terminals with a total of five concourses. Terminal 1 handles domestic flights and international flights to/from Canada. Other international flights use Terminal 2, as does Southwest Airlines It was possible to walk between the terminals via Concourse D until the connection was blocked in 2008 with the closure of Concourse D.[119]

Terminal 1 opened in 1956 along with several single story concourses. The terminal itself would be expanded in the 1960s, while Concourses A and C were rebuilt as two-story buildings with jetbridges in the early 1970s. Expansion by both Ozark Airlines and Trans World Airlines forced the construction of Concourse D in the early 1980s. Up until its demise, TWA operated an enormous domestic hub out of Terminal 1. From 2008 to 2016, Lambert comprehensively renovated Terminal 1, which came to include considerable repairs following a tornado that struck the airport in 2011. The terminal features an American Airlines Admirals Club and one of the largest USO facilities in the nation.[120][121]

- Concourse A contains 15 gates[122]

- Concourse B contains 10 gates and is vacant.[122]

- Concourse C contains 30 gates.[122]

- Concourse D contains 13 gates and is vacant.[122]

Terminal 2 opened in 1998 and was built in order to accommodate the growing presence of Southwest in the St. Louis market. The concourse also handles all international arrivals (excluding pre-cleared international flights). As Southwest has continued to expand in St. Louis, former unused gates in the D concourse have been renovated and renamed as E gates. In January 2018, a new common-use lounge, operated by Wingtips, opened near gate E31.[123]

- Concourse E contains 18 gates.[122]

Ground transportation

Metro Train To City The airport is connected to MetroLink's Red Line via stations at both Terminal 1[124] and Terminal 2. MetroLink lines provide direct or indirect service to downtown St. Louis, the Clayton area and Illinois suburbs in St. Clair County.

Two MetroBus lines serve the Lambert Bus Port, which is located next to the intermediate parking lot and is accessible via a tunnel from Terminal 1.[125]

The airport is served by I-70; eastbound leads to downtown St. Louis and Illinois with a north/south connection at I-170 immediately east of the airport, while westbound leads to St. Louis exurbs in St. Charles County with a north/south connection at I-270 immediately west of the airport.

Art and historical pieces

Black Americans in Flight is a mural that depicts African American aviators and their contributions to aviation since 1917. It is located in Terminal 1 / Main Terminal on the lower level near the entrance to gates C and D and baggage claim. The mural consists of five panels and measures 8 feet tall and 51 feet long. The first panel includes Albert Edward Forsythe and C. Alfred Anderson, the first black pilots to complete a cross-country flight, the Tuskegee Institute and the Tuskegee Airmen, Eugene Bullard, Bessie Coleman and Willa Brown (first African American woman commercial pilot in United States). The second panel shows Benjamin O. Davis Jr., Clarence "Lucky" Lester and Joseph Ellesberry. The third panel shows Gen. Daniel "Chappie" James, Capt. Ronald Radliff and Capt. Marcella Hayes. The fourth and fifth panels show Ronald McNair, who died in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, Guion Bluford, who in 1983 became the first African American in space, and Mae Jemison, the first African America woman in space. Spencer Taylor and Solomon Thurman created the mural in 1990.[126][127] The mural had a re-dedication ceremony in 2012.[128]

One aircraft from the Missouri History Museum currently hangs from Lambert's ceilings. This aircraft, a red Monocoupe 110 Special manufactured in St. Louis in 1931, hangs in the ticketing hall of Terminal 2.[129] The airport has also played host to two other aircraft. A Monocoupe D-127 hung near the eastern security checkpoint in Terminal 1. Charles Lindbergh bought it in 1934 from the Lambert Aircraft Corporation and flew it as his personal aircraft. It was removed in 2018 and returned to the Missouri Historical Society, from which the aircraft had been on loan since 1979, for preservation purposes.[130] Until 1998, a Ryan B-1 Brougham, a replica of the Spirit of St. Louis, hung next to the D-127.[131]

Cargo

In 2013, a Texas company, Brownsville International Air Cargo Inc., expressed interest in building a dual-customs cargo facility on the site of the old McDonnell-Douglas complex on the north end of Lambert, citing excess airport capacity and a central U.S. location as conducive to a cargo operation. The idea was positively received by St. Louis and airport officials and won local approval, culminating in a three-year agreement to prepare studies and applications for the facility in late 2014. This dual-customs facility would permit pre-clearance of cargo bound for Mexico as well as U.S. Customs inspection of cargo imported from Mexico.[132][133]

The airport stated it was heavily focused on increasing cargo traffic as part of its 2015 Five Year Strategic Plan.[134] To this end, the airport supported an extendable 20-year lease on 49 acres of airport land in order for it to be redeveloped into a large international air-cargo facility in three phases over 18 months. This lease was signed with Bi-National Gateway Terminal LLC and owner Ricardo Nicolopulos, who also owns Brownsville International Air Cargo Inc., and would incorporate the proposed dual-customs facility into the final design of the air-cargo facility, pending its approval by the Mexican government. Nicolopulos stated that Bi-National would invest $77 million into the first phase of the project, which would cover 32 acres and include a new international air-cargo terminal, and would not require extra funding from the airport. He reiterated his interest in and support of developing cargo operations in St. Louis, stating his belief that St. Louis could become a viable cargo competitor to Miami. The airport stands to receive at least $13.5 million in revenue from the facility over the initial 20-year lease.[135]

In January 2017, the Bi-National cargo facility was included on a list of important national infrastructure projects compiled by President Donald Trump's administration. The report stated overall construction costs of $1.8 billion and claimed that the facility could create 1,800 'direct' jobs.[136]

As of August 2017, no construction on the cargo facility has occurred; Bi-National has, however, filed a Brownfield Grant application with the state of Missouri in order to receive financial assistance for environmental cleanup of the site, and has also filed a Tenant Construction Application with the airport.[137] Furthermore, Lambert airport, along with St. Louis County, have begun to undertake infrastructure improvements in order to better accommodate future shipping needs in and around the airport. The first of these was a rebuilding of Taxiway V and the taxiway's entrance to the "Northern Tract" of Lambert, providing common-use access to the Trans States Airlines ramp, the Airport Terminal Services ramp, and the Bi-National Air Cargo ramp. The rebuilt taxiway can accommodate the largest cargo aircraft, up to and including the Boeing 747-8F. The taxiway reconstruction cost approximately $6.1 million, funded via a grant from the Missouri Department of Transportation, and was finished in 2017.[138] Other projects include the reconstruction of several roads leading to the airport to better facilitate heavy truck traffic and an extension of the Class 1 rail line adjacent to the airport to provide immediate train access from the Northern Tract cargo facilities. The overall projected cost for these near-term improvements is $20.7 million.[139][140] Additionally, the airport is in the final stage of approval to become a USDA port of embarkation, allowing live animal charters to depart from St. Louis.[141]

In October 2017 the Ambassador of Mexico visited to discuss trade between St. Louis and Mexico. Also beginning in October was the aforementioned environmental cleanup of the cargo facility site.[142]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

Cargo

| Airlines | Destinations | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Amazon Air | Baltimore, Ontario | [155] |

| DHL Aviation | Cincinnati, Omaha | |

| FedEx Express | Indianapolis, Memphis, Minneapolis/St. Paul | |

| UPS Airlines | Boise, Chicago-Rockford, Louisville, Portland (OR) |

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Atlanta, Georgia | 250,660 | Delta, Southwest |

| 2 | Denver, Colorado | 228,370 | Frontier, Southwest, United |

| 3 | Dallas/Fort Worth, Texas | 170,280 | American |

| 4 | Orlando, Florida | 165,030 | Delta, Frontier, Southwest |

| 5 | Phoenix, Arizona | 154,710 | American, Southwest |

| 6 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 150,870 | American, United |

| 7 | Las Vegas, Nevada | 139,030 | Frontier, Southwest, Sun Country |

| 8 | Dallas–Love, Texas | 132,040 | Southwest |

| 9 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 131,960 | American |

| 10 | Chicago–Midway, Illinois | 106,020 | Southwest |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Southwest Airlines | 4,754,000 | 62.78% |

| 2 | American Airlines | 885,000 | 11.69% |

| 3 | Delta Air Lines | 574,000 | 7.59% |

| 4 | Frontier Airlines | 212,000 | 2.80% |

| 5 | Republic Airways | 176,000 | 2.33% |

| 6 | Others | 971,000 | 12.82% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 25,719,351 | 2005 | 14,697,263 | 2015 | 12,752,331 |

| 1996 | 27,274,846 | 2006 | 15,205,944 | 2016 | 13,959,126 |

| 1997 | 27,661,144 | 2007 | 15,384,557 | 2017 | 14,730,656 |

| 1998 | 28,700,622 | 2008 | 14,431,471 | 2018 | 15,632,586 |

| 1999 | 30,188,973 | 2009 | 12,796,302 | 2019 | 15,878,527 |

| 2000 | 30,558,991 | 2010 | 12,331,426 | 2020 | 6,302,402 |

| 2001 | 26,695,019 | 2011 | 12,526,150 | 2021 | |

| 2002 | 25,626,114 | 2012 | 12,688,726 | 2022 | |

| 2003 | 20,431,132 | 2013 | 12,570,128 | 2023 | |

| 2004 | 13,396,028 | 2014 | 12,384,015 | 2024 |

Accidents and incidents

Accidents

- August 5, 1936: Chicago and Southern Flight 4, a Lockheed 10 Electra headed for Chicago, crashed after takeoff, killing all eight passengers and crew. The pilot became disoriented in fog.

- January 23, 1941: a Douglas DC-3 of Transcontinental & Western Air crashed 0.4 miles west of St. Louis Municipal Airport during a landing attempt in adverse weather, killing two occupants out of the 14 on board.[157]

- August 1, 1943: during a demonstration flight of an "all St. Louis-built glider", a Waco CG-4A, USAAF serial 42-78839, built by sub-contractor Robertson Aircraft Company, lost its starboard wing due to a defective wing strut support and plummeted vertically to the ground at Lambert Field, killing all on board, including St. Louis Mayor William D. Becker; Maj. William B. Robertson and Harold Krueger, both of Robertson Aircraft; Thomas Dysart, president of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce; Max Doyne, director of public utilities; Charles Cunningham, department comptroller; and Henry Mueller, St. Louis Court presiding judge.[158] The failed component had been manufactured by Robertson subcontractor Gardner Metal Products Company, of St. Louis, which, coincidentally, had been a casket maker.[159]

- September 6, 1944: the starboard engine of the sole completed McDonnell XP-67 fighter prototype, USAAF serial 42-11677, caught fire during a test flight. Test pilot E.E. Elliot executed an emergency landing at Lambert Field and escaped, but the fire rapidly spread, destroying the aircraft. This event was a crippling setback for the XP-67; the program had already been plagued by delays and technical problems, and the other prototype was only 15% complete, so flight testing could not promptly resume. Soon after the accident, United States Army Air Forces leaders declared the XP-67 unnecessary, canceling the program.[160]

- May 24, 1953: a Meteor Air Transport Douglas DC-3 crashed on approach to the airport, killing six of the seven people on board.[161]

- February 28, 1966: astronauts Elliot See and Charles Bassett – the original crew of the Gemini 9 mission – were killed in the crash of their T-38 trainer while attempting to land at Lambert Field in bad weather. The aircraft crashed into the same McDonnell Aircraft Corporation building (adjacent to the airport) where their spacecraft was being assembled.[162]

- March 20, 1968: a McDonnell F-4 Phantom II jet fighter crashed on takeoff during a test flight. The aircraft pitched up and stalled almost immediately after lifting from the runway; both crewmen were able to eject and were not seriously injured. The aircraft was destroyed in the ensuing explosion and fire. The crash was allegedly caused by a wrench socket, mistakenly left in the cockpit by maintenance crews, becoming lodged inside the control stick well on takeoff, jamming the stick in the full aft position.[163]

- March 27, 1968: at about 6 p.m., an Ozark DC-9, operating as Flight 965, and a Cessna 150F on a training flight collided in flight approximately 1.5 miles north of the airport. Both aircraft were in the landing pattern for Runway 17 when the accident occurred. The Cessna was destroyed by the collision and ground impact, and both occupants were fatally injured. The DC-9 sustained light damage and was able to effect a safe landing. None of its 44 passengers or five crewmembers were injured. The probable cause was determined to be a combination of inadequate VFR procedures in place at the airport, the failure of the DC-9 crew to notice the other aircraft in time, the controller's failure to ensure that the Cessna had received and understood important landing information, and the Cessna crew's deviation from their traffic pattern instructions and/or their continuation to a critical point in the traffic pattern without informing the controller of the progress of the flight.[164]

- July 23, 1973: while on the approach to land at St. Louis International Airport, Ozark Air Lines Flight 809 crashed near the University of Missouri – St. Louis, killing 38 of the 44 persons on board. Wind shear was cited as the cause. A tornado had been reported at Ladue, Missouri about the time of the accident but the National Weather Service did not confirm that there was a tornado.[165]

- July 6, 1977: a Fleming International Airways Lockheed L-188 Electra, a cargo flight, crashed during the takeoff roll; all three occupants were killed.[166]

- January 9, 1984: Douglas DC-3 registration C-GSCA of Skycraft Air Transport crashed on take-off, killing one of its two crew members. The aircraft was on an international cargo flight to Toronto Pearson International Airport, Canada. Both engines lost power shortly after take-off. The aircraft had been fueled with jet fuel instead of avgas.[167]

- April 8, 1990: A Missouri Air National Guard F-4 Phantom II veered off the runway during takeoff, crashed, and burst into flames. The pilot suffered minor injuries after his ejection seat failed to deploy and he was forced to exit the burning wreckage, while the weapons officer fractured his left leg when he ejected from the aircraft.[168]

- November 22, 1994: TWA Flight 427 collided with a Cessna 441 Conquest, registration N441KM, at the intersection of runway 30R and taxiway Romeo. The TWA McDonnell Douglas MD-82 was taking off for Denver and had accelerated through 80 knots when the collision occurred. The MD-82 sustained substantial damage during the collision. The Cessna 441, operated by Superior Aviation, was destroyed. The pilot and the passenger were killed. The investigation found the Cessna 441 had entered the wrong runway for its takeoff.[169]

References

- "CY2018 Passenger & Operation Statistics". St. Louis Lambert International Airport. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- FAA Airport Form 5010 for STL PDF. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- "Departure Statistics". Lambert–St. Louis International Airport. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- "The History of Lambert – St. Louis International Airport". Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. 2005. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- Henry, Prince Joe (December 7, 2007). "Joe Gains Another Admirer: Kinloch's Sergeant of Police". River Front Times. Riverfront Times, LLC. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- John Aaron Wright (2000). Kinloch: Missouri's first black city. ISBN 9780738507774. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- "Lambert History". Lambert-Saint Louis International Airport. Archived from the original on August 22, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- Christensen, Lawrence O. (1999). Dictionary of Missouri Biography. University of Missouri Press. p. 469. ISBN 0-8262-1222-0. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- "Lambert – St. Louis International Airport > About Lambert > History > Timeline". July 22, 2012. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Mola, Roger. "Aircraft Landing Technology". U. S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- "Robertson Air Lines". www.timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Robertson Air Lines". www.timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Timetable" (JPG). www.timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- "Timetable" (JPG). www.timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2008. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- "Timetable" (JPG). www.timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- "Timetable" (JPG). www.timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- "Timetable" (JPG). www.timetableimages.com. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- "Curtis Wright airline factory" (PDF). dnr.mo.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- Lambert, St Louis (July 12, 2016). "History – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Lambert expansion: the never-ending story". Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Hampel, Paul. "Main Lambert terminal gets shiny, new roof". Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- St Louis Post-Dispatch 22 July 1959 p3

- "Facility Orientation Guide – St. Louis Air Traffic Control Tower" (PDF). FAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- Continuing Progress at Lambert. City of St. Louis Airport Authority. 1977.

- "Timeline". City of St. Louis Airport Authority. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- "Lambert International: Architectural Creativity in Steel" (PDF). Modern Steel Construction. Chicago: American Institute of Steel Construction, Inc. 26 (1): 5–9. 1986. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- Handbook of Airline Statistics (biannual CAB publication)

- "Airlines and Aircraft Serving Saint Louis Effective November 15, 1979". DepartedFlights.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- "STL: How To Build A Hub". TWA Mainliner. October 11, 1982. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- "History". Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- Fare and Service Changes at St. Louis Since the TWA-Ozark Merger Archived August 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, United States General Accounting Office. September 21, 1988. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- "TWA to relocate headquarters to St. Louis". Archived from the original on July 24, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Historical Passenger Statistics Since 1990" (PDF). www.flystl.com. STL Airport. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- "The Expansion Story". Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- Stoller, Gary (January 9, 2007). "St. Louis' Airports Aren't Too Loud: They're Too Quiet". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 18, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- "Airport/Mass Transit November 2005 – Feature Story". Engineering News-Record. November 1, 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- "Airports and Cities: Can they coexist?". SD Earth Times. Archived from the original on March 16, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- "Historical Operation Statistics by Class for the Years: 1985–2006". Lambert–St. Louis International Airport. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- "New $1 Billion Runway Opens This Week, But It's Not Needed Anymore". USA Today. April 11, 2006. Archived from the original on August 30, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- "Noise management report" (PDF). www.flystl.com. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- HIRSCHFELD, SIMON (April 10, 2001). "AMR's Takeover of TWA Finalized". Archived from the original on October 12, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2018 – via LA Times.

- "TWA's Last Flight". twaseniorsclub.org. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Stories" (PDF). www.bizjournals.com. December 24, 2001. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- "The Last Day of TWA – A Sad Day For Aviation — Avgeekery.com – News and stories by Aviation Professionals". www.avgeekery.com. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "TWA to be bought by American – Jan. 10, 2001". money.cnn.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Bureau of Transportation Statistics". Bureau of Transportation. Archived from the original on July 19, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- "American Airlines, a History of Unsuccessful Mergers". Dallas News. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- "AA to cut back St. Louis operations: Travel Weekly". www.travelweekly.com.

- "Info" (PDF). www.airtimes.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 26, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Grant, Elaine X. (July 28, 2006). "TWA – Death Of A Legend". Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Info" (PDF). www.airtimes.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- "Airtimes for early 2000s American Airlines flights at Lambert Airport" (PDF). airtimes.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Last two F-15's leave Lambert". St. Louis Public Radio. June 15, 2009. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "Missouri Air National Guard celebrates End of Era with final F-15 departure". Whiteman AFB Home Page. July 6, 2016. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "American Airlines Flight 2470 – First Commercial Airliner to Land on …". February 22, 2013. Archived from the original on February 22, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "St. Louis Int'l Modernizes Iconic Terminal Without Losing Connection to the Past – Airport Improvement Magazine". www.airportimprovement.com. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Hinton, Christopher. "American Airlines to trim capacity, add new bag fee". Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- USA Today, Fuel-Cost Fallout: American Airlines is the latest carrier to cut routes, flights, retrieved July 26, 2013 Archived March 19, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Mutzabaugh, Ben (September 18, 2009). "With AA's Cuts, St. Louis Will Fall From the Ranks of Hub Cities". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- Leiser, Ken (September 18, 2009). "Airline blames cuts on restructuring". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- "American Airlines' "cornerstone" worldview". Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Consultants: We studied possibility of closing down one of American Airlines 'cornerstone' cities". April 26, 2012. Archived from the original on November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Moseley, Jace (August 7, 2017). "The Near Death and Resurgence of St. Louis International Airport". AirlineGeeks.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- "Southwest to Add Five More New Destinations from St. Louis in May". Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- April 22nd Tornadic Supercell Greater St. Louis Metropolitan Area Archived April 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, National Weather Service, St. Louis, Missouri. (April 23, 2011).

- Held, Kevin (April 23, 2011). "St. Louis Airport Storm Caught on Camera". KSDK. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Gay, Malcolm; Harris, Elizabeth A. (April 23, 2011). "Tornadoes Tear Through St. Louis, Shutting Down the Airport". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Bowers, Cynthia (April 23, 2011). "Residents: St. Louis Was "Bedlam" During Tornado". CBS News. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- Salter, Jim; Suhr, Jim (April 23, 2011). "Tornado Cleanup Starts Quickly in St. Louis Area". Yahoo! News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Moore, Bryce (April 23, 2011). "Lambert Passengers Watch Plane Move, Then Evacuate Terminal". Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "UPDATE: Lambert Reopening Today, Expects to Be at 70 Percent Capacity Sunday". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. April 23, 2011. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- Leiser, Ken. "Lambert Opens Refurbished C Concourse After Twister". St. Louis Post Dispatch. Archived from the original on July 6, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2012.

- Peterson, Deb (November 8, 2011). "No Joke – TSA Names Lambert 'Airport of the Year'". St. Louis Post Dispatch. Archived from the original on November 10, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- "Kwame Building Group – Lambert-St. Louis International – Airport Experience Program". October 17, 2015. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Lambert-St. Louis Int'l. website, Retrieved July 19, 2013". Archived from the original on March 19, 2014.

- "lam6535 Brochure_insert.ai" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Retrieved September 9, 2016". Bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Post-Dispatch store. "Retrieved September 9, 2016". Stltoday.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- On Air 9:52AM (September 7, 2016). "Retrieved September 9, 2016". Ksdk.com. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Thorsen, Leah (October 26, 2016). "Airport in St. Louis likely will get a new name; FAA approval still needed". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- Thorsen, Leah. "It's official: St. Louis Lambert International Airport is our airport's new name". Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- Manager, Dan Fredman Digital Content. "With Southwest expansion in mind, Lambert renovations underway". Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Lambert, St Louis (May 18, 2017). "Southwest Airlines Announces STL as International Gateway – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Agencies Boost STL's Outlook Ahead of Bond Refunding". Lambert Airport. May 30, 2017. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- "Fitch Upgrades St. Louis Lambert Int'l Airport (MO) to 'A-'; Outlook Revised to Stable". Fitch Ratings. October 6, 2017. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved January 18, 2018.

- "Press Release – U.S. Department of Transportation Announces $282.6 Million in Infrastructure Grants to 67 Airports in 29 States". FAA. August 21, 2017. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 22, 2017.

- Mutzabaugh, Ben (August 23, 2017). "WOW Air, known for $99 Europe fares, adds four new U.S. cities". USA Today. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- "Wow Air expands planned Lambert flights, offers more $99 fares to Iceland". STLToday. January 25, 2018. Archived from the original on June 1, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- "Tourism and Business Are Winners with New WOW Air Service between STL and Iceland". Lambert Airport. May 21, 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- Thorsen, Leah. "Wow, that was quick: Wow Air to end flights from Lambert in January". St. Louis Post Dispatch. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- Lambert, St Louis (October 15, 2018). "Announcement Regarding WOW air – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on October 17, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "American Airlines to close St. Louis pilot base in September 2018". October 30, 2017. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "153 pilots affected in American Airlines closure" (PDF). www.bizjournals.com. July 6, 2018.

- "American Airlines Inc" (PDF). jobs.mo.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- Lambert, St Louis (March 2, 2018). "STL Airlines to Invest $50 million for Jet Fuel Storage Facility – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Construction Begins on New Jet Fuel Storage Facility at STL". August 28, 2019. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- "New airline offering direct flights from St. Louis to Tampa and Ft. Myers". June 26, 2018. Archived from the original on June 29, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Sun Country Airlines announces two new destinations from Lambert | News Headlines". kmov.com. January 8, 2019. Archived from the original on January 28, 2019. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- "Lambert airport to receive $10 million federal grant for runway repair" (PDF). www.bizjournals.com. July 17, 2018.

- "TSA announces new X-ray technology roll-out plan". July 30, 2018. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Lambert, St Louis (August 8, 2018). "Moody's Upgrades STL Airport Bonds to A2, Outlook Stable – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Lambert, St Louis (October 9, 2018). "Fitch Ratings Issues Positive Outlook for Airport Revenue Bonds – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "RFQ for Terminal 2 Baggage Carousel Expansion at St. Louis Lambert International Airport – Board of Public Service". www.stl-bps.org. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Public notice" (PDF). www.flystl.com. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2018. Retrieved November 24, 2018.

- "RFQ – Design Services for Terminal 2 Baggage Carousel Expansion Lambert airport – Updated 11-12-18 *List May Not Be Current* – Board of Public Service". www.stl-bps.org. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Lambert, St Louis (October 3, 2018). "STL, Southwest Airlines Commit to Expanding T2 Bag Claim – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Schlinkmann, Mark. "Lambert plans a third baggage carousel in Southwest terminal". Archived from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Moody's assigns A2 to St. Louis, MO Airport's Series 2019 Airport Revenue and Refunding Bonds; outlook is stable". Moody's Investors Service. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- "S&P Raises Long-term Rating on STL's Revenue Bonds". Fly STL. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 7, 2019.

- "Fitch upgrades Lambert airport debt, expects continued traffic increase". STL Business Journal. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

- Long, James. "St. Louis Lambert airport to receive $5.29 grant for improvements". Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- "Bureau of Transportation Statistics – St. Louis International Airport". BTS. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- Thorsen, Leah. "Slay wants to look at putting Lambert airport under private management". Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Altman, Maria. "FAA accepts initial application for Lambert privatization". Archived from the original on October 13, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "AirNav: KSTL – St Louis Lambert International Airport". www.airnav.com. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "World's sky-high civilian air traffic control towers". wordpress.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "Lambert St. Louis Airport Control Tower, Bridgeton". emporis.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "St. Louis Airport Reopens, One Concourse Remains Closed". Travelpulse.com. April 25, 2011. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2011.

- "American Airlines Admirals Club St. Louis Airport". sleepinginairports.net. Archived from the original on August 4, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- James S. McDonnell USO Archived January 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "STL Airport Diagram" (PDF). flystl.com. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Clever, Boxing (January 4, 2018). "Wingtips St. Louis Lounge Opens in STL's Terminal 2 – St. Louis Lambert International Airport". Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- "MetroLink". Metrostlouis.org Site. April 8, 2019. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- "St. Louis Airport Bus". www.saint-louis-airport.com. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- Brownlee Jr., Henry T. (February 2010). "Linking the Past to the Future" (PDF). Boeing Frontiers. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 12, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

- "Many St. Louis Sites Significant in Black History: "Black Americans in Flight" Mural". St. Louis Convention & Visitors Commission. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

- Gooden, Christian. "Lambert rededicates its "Black Americans In Flight" mural". Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Charles Lindbergh's Monocoupe – St. Louis, MO – Static Aircraft Displays". Groundspeak, Inc. December 15, 2008. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- "Lindbergh Monocoupe Exhibit Ending its Run at STL Airport". Lambert Airport. June 7, 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- Mullen, Robert; Smith, Sharon (Spring 2008). "Midnight Maintenance: Caring for Lindbergh's Monocoupe". Missouri History Museum. Archived from the original on April 19, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- "Lambert backs development of Mexican cargo facility". STLToday. November 6, 2013. Archived from the original on February 18, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "Dual customs facility at Lambert gets key support". STLToday. October 3, 2014. Archived from the original on August 27, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "Lambert airport leaders to stress cargo, private partnerships in next five years". STLToday. February 4, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "Plans for air-cargo terminal at Lambert move forward". STLToday. May 6, 2015. Archived from the original on May 3, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2017.

- "Air-cargo facility at Lambert named in report of Trump-backed projects". STLToday. January 24, 2017. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- "January 2017 Airport Commission Meeting Minutes" (PDF). January 4, 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- "Project sheets" (PDF). www.thefreightway.com. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2018. Retrieved August 8, 2018.

- "2017 FREIGHT DEVELOPMENT PLAN ST LOUIS REGIONAL FREIGHTWAY" (PDF). www.thefreightway.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "St. Louis Regional Freightway – 2016 Freight Development Project List" (PDF). www.thefreightway.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2017. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- "Project list" (PDF). www.thefreightway.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- "St. Louis Airport Commission Meeting October Minutes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 10, 2017. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "Air Canada flight schedules". Air Canada. Archived from the original on September 25, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Air Choice One at St. Louis". Archived from the original on June 27, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Alaska Airlines flight timetable". alaskaair.com. Alaska Airlines. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "American Airlines flight schedules and notifications". aa.com. American Airlines. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Cape Air schedules". Cape Air. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- "Contour Airlines to announce jet service". sustainableozarks.org. Archived from the original on December 27, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- "Flight schedules for Delta". Delta Air Lines. Archived from the original on June 21, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Frontier Airlines schedule". Frontier Airlines. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "Southwest Airlines Spring And Summer Schedules Take Off".

- "Southwest Flight schedules". Southwest Airlines. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- "Route Map & Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "United Airlines timetable". United Airlines. Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- "ABX Air 3943 ✈ FlightAware". Flightaware.com. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- "Historical Passenger Activity" (PDF). St. Louis Lambert International Airport. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- Accident description for NC17315 at the Aviation Safety Network

- Bowers, Peter M., "Breezing Along with the Breeze", Wings, Granada Hills, California, December 1989, Volume 19, Number 6, p. 19.

- Diehl, Alan E., PhD, "Silent Knights: Blowing the Whistle on Military Accidents and Their Cover-ups", Brassey's, Inc., Dulles, Virginia, 2002, Library of Congress card number 2001052726, ISBN 978-1-57488-412-8, pages 81–82.

- Mesko, Jim (2002). FH Phantom/F2H Banshee in action. Carrollton, Texas, United States: Squadron/Signal Publications, Inc. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-89747-444-9.

- Accident description for N53596 at the Aviation Safety Network

- "Losing The Moon". St. Louis Magazine. May 2006. Archived from the original on March 19, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- CriticalPast (May 6, 2014). "US Navy F-4J Phantom II aircraft takeoff and crash in St. Louis, Missouri; Fireme...HD Stock Footage". Archived from the original on April 11, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2019 – via YouTube.

- "Accident report" (PDF). 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 15, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2018.

- St. Louis, MO Airliner Crashes On Landing, July 1973 | GenDisasters ... Genealogy in Tragedy, Disasters, Fires, Floods Archived May 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. .gendisasters.com. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- Accident description for N280F at the Aviation Safety Network

- "C-GSCA Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- "F-4 crashes; no fatalities". UPI. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Aircraft Accident Report, Runway Collision Involving Trans World Airlines Flight 427 And Superior Aviation Cessna 441, Bridgeton, Missouri, November 22, 1994 (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. August 30, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lambert-St. Louis International Airport. |

- St. Louis Lambert International Airport official site

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective January 28, 2021

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KSTL

- ASN accident history for STL

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KSTL

- FAA current STL delay information

- OpenNav airspace and charts for KSTL