Thomas Babington Macaulay

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, FRS FRSE PC (25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician. He wrote extensively as an essayist, on contemporary and historical sociopolitical subjects, and as a reviewer. His The History of England was a seminal and paradigmatic example of Whig historiography, and its literary style has remained an object of praise since its publication, including subsequent to the widespread condemnation of its historical contentions which became popular in the 20th century.[1]

The Lord Macaulay | |

|---|---|

Photogravure of Macaulay by Antoine Claudet | |

| Secretary at War | |

| In office 27 September 1839 – 30 August 1841 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Preceded by | Viscount Howick |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Hardinge |

| Paymaster-General | |

| In office 7 July 1846 – 8 May 1848 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | Lord John Russell |

| Preceded by | Hon. Bingham Baring |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Granville |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 October 1800 Leicestershire, England |

| Died | 28 December 1859 (aged 59) London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Whig |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Signature | |

Macaulay served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1848. He played a major role in the introduction of English and western concepts to education in India, and published his argument on the subject in the "Macaulay's Minute" in 1835. He supported the replacement of Persian by English as the official language, the use of English as the medium of instruction in all schools, and the training of English-speaking Indians as teachers.[1] On the flip side, this led to Macaulayism in India, and the systematic wiping out of traditional and ancient Indian education and vocational systems and sciences.[2]

Macaulay divided the world into civilised nations and barbarism, with Britain representing the high point of civilisation. In his Minute on Indian Education of February 1835, he asserted, "It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgement used at preparatory schools in England".[3] He was wedded to the idea of progress, especially in terms of the liberal freedoms. He opposed radicalism while idealising historic British culture and traditions.[1]

Early life

Macaulay was born at Rothley Temple[4] in Leicestershire on 25 October 1800, the son of Zachary Macaulay, a Scottish Highlander, who became a colonial governor and abolitionist, and Selina Mills of Bristol, a former pupil of Hannah More.[5] They named their first child after his uncle Thomas Babington, a Leicestershire landowner and politician,[6][7] who had married Zachary's sister Jean.[8] The young Macaulay was noted as a child prodigy; as a toddler, gazing out of the window from his cot at the chimneys of a local factory, he is reputed to have asked his father whether the smoke came from the fires of hell.[9]

He was educated at a private school in Hertfordshire, and, subsequently, at Trinity College, Cambridge.[10] Whilst at Cambridge, Macaulay wrote much poetry and won several prizes, including the Chancellor's Gold Medal in June 1821.[11]

In 1825, Macaulay published a prominent essay on Milton in the Edinburgh Review. He studied law, and in 1826 he was called to the bar, but he soon took more interest in a political career.[12] In 1827, Macaulay published an anti-slavery essay, in the Edinburgh Review, in which he contested the analysis of African labourers composed by Colonel Thomas Moody, Knight, who was the Parliamentary Commissioner for West Indian slavery.[13][14] Macaulay's father, Zachary Macaulay, had also condemned the philosophy of Moody, in a series of letters to the Anti-Slavery Reporter.[13][15]

Macaulay, who never married and had no children, was rumoured to have fallen in love with Maria Kinnaird, who was the wealthy ward of Richard "Conversation" Sharp.[16] Macaulay's strongest emotional ties were to his youngest sisters: Margaret, who died while he was in India, and Hannah. As Hannah grew older, he formed a close attachment to Hannah's daughter Margaret, whom he called "Baba".[17]

Macaulay retained a passionate interest in western classical literature throughout his life, and prided himself on his knowledge of Ancient Greek literature. He likely had an eidetic memory.[18] While in India, he read every ancient Greek and Roman work that was available to him. In his letters, he describes reading the Aeneid whilst on vacation in Malvern in 1851, and being moved to tears by the beauty of Virgil's poetry. He also taught himself German, Dutch, and Spanish, and remained fluent in French.[19]

Political career

In 1830 the Marquess of Lansdowne invited Macaulay to become Member of Parliament for the pocket borough of Calne. His maiden speech was in favour of abolishing the civil disabilities of the Jews in the UK.[11]

Macaulay made his name with a series of speeches in favour of parliamentary reform.[11] After the Great Reform Act of 1833 was passed, he became MP for Leeds.[11] In the Reform, Calne's representation was reduced from two to one; Leeds had never been represented before, but now had two members. Though proud to have helped pass the Reform Bill, Macaulay never ceased to be grateful to his former patron, Lansdowne, who remained a great friend and political ally.

India (1834–1838)

Macaulay was Secretary to the Board of Control under Lord Grey from 1832 until 1833. The financial embarrassment of his father meant that Macaulay became the sole means of support for his family and needed a more remunerative post than he could hold as an MP. After the passing of the Government of India Act 1833, he resigned as MP for Leeds and was appointed as the first Law Member of the Governor-General's Council. He went to India in 1834, and served on the Supreme Council of India between 1834 and 1838.[20]

In his well-known Minute on Indian Education of February 1835,[3] Macaulay urged Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General to reform secondary education on utilitarian lines to deliver "useful learning" – a phrase that to Macaulay was synonymous with Western culture. There was no tradition of secondary education in vernacular languages; the institutions then supported by the East India Company taught either in Sanskrit or Persian. Hence, he argued, "We have to educate a people who cannot at present be educated by means of their mother-tongue. We must teach them some foreign language." Macaulay argued that Sanskrit and Persian were no more accessible than English to the speakers of the Indian vernacular languages and existing Sanskrit and Persian texts were of little use for 'useful learning'. In one of the less scathing passages of the Minute he wrote:

I have no knowledge of either Sanskrit or Arabic. But I have done what I could to form a correct estimate of their value. I have read translations of the most celebrated Arabic and Sanskrit works. I have conversed both here and at home with men distinguished by their proficiency in the Eastern tongues. I am quite ready to take the Oriental learning at the valuation of the Orientalists themselves. I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.[3]

Neither Sanskrit nor Arabic poetry matched that of Europe; in other branches of learning the disparity was even greater, he argued:

It will hardly be disputed, I suppose, that the department of literature in which the Eastern writers stand highest is poetry. And I certainly never met with any orientalist who ventured to maintain that the Arabic and Sanskrit poetry could be compared to that of the great European nations. But when we pass from works of imagination to works in which facts are recorded and general principles investigated, the superiority of the Europeans becomes absolutely immeasurable. It is, I believe, no exaggeration to say that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgments used at preparatory schools in England. In every branch of physical or moral philosophy, the relative position of the two nations is nearly the same.[3]

Hence, from the sixth year of schooling onwards, instruction should be in European learning, with English as the medium of instruction. This would create a class of anglicised Indians who would serve as cultural intermediaries between the British and the Indians; the creation of such a class was necessary before any reform of vernacular education:[20][3]

I feel... that it is impossible for us, with our limited means, to attempt to educate the body of the people. We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, – a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect. To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from the Western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.

Macaulay's minute largely coincided with Bentinck's views[21] and Bentinck's English Education Act 1835 closely matched Macaulay's recommendations (in 1836, a school named La Martinière, founded by Major General Claude Martin, had one of its houses named after him), but subsequent Governors-General took a more conciliatory approach to existing Indian education.

His final years in India were devoted to the creation of a Penal Code, as the leading member of the Law Commission. In the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Macaulay's criminal law proposal was enacted. The Indian Penal Code in 1860 was followed by the Criminal Procedure Code in 1872 and the Civil Procedure Code in 1908. The Indian Penal Code inspired counterparts in most other British colonies, and to date many of these laws are still in effect in places as far apart as Pakistan, Singapore, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, as well as in India itself.[22]

In Indian culture, the term "Macaulay's Children" is sometimes used to refer to people born of Indian ancestry who adopt Western culture as a lifestyle, or display attitudes influenced by colonisers ("Macaulayism")[23] – expressions used disparagingly, and with the implication of disloyalty to one's country and one's heritage. In independent India, Macaulay's idea of the civilising mission has been used by Dalitists, in particular by neoliberalist Chandra Bhan Prasad, as a "creative appropriation for self-empowerment", based on the view that Dalit folk are empowered by Macaulay's deprecation of Hindu civilisation and an English education.[24]

Domenico Losurdo states that "Macaulay acknowledged that the English colonists in India behaved like Spartans confronting helots: we are dealing with 'a race of sovereign' or a 'sovereign caste', wielding absolute power over its 'serfs'."[25] But this did not prompt any doubts about the right of free England to exercise dictatorship over the barbarians of the colonies. It was a dictatorship that could take the most ruthless forms. Macaulay powerfully describes how the governor of India, Warren Hastings, proceeded when he had to confront the colony's native population. Macaulay concluded that "All the injustice of former oppressors, Asiatic and European, appeared as a blessing when compared with the justice of the Supreme Court." Macaulay adds, for having saved England and civilisation, Hastings deserved "high admiration" and to rank among "the most remarkable men in our history".[26]

Return to British public life (1838–1857)

Returning to Britain in 1838, he became MP for Edinburgh in the following year. He was made Secretary at War in 1839 by Lord Melbourne and was sworn of the Privy Council the same year.[27] In 1841 Macaulay addressed the issue of copyright law. Macaulay's position, slightly modified, became the basis of copyright law in the English-speaking world for many decades.[28] Macaulay argued that copyright is a monopoly and as such has generally negative effects on society.[28] After the fall of Melbourne's government in 1841 Macaulay devoted more time to literary work, and returned to office as Paymaster-General in 1846 in Lord John Russell's administration.

In the election of 1847 he lost his seat in Edinburgh.[29] He attributed the loss to the anger of religious zealots over his speech in favour of expanding the annual government grant to Maynooth College in Ireland, which trained young men for the Catholic priesthood; some observers also attributed his loss to his neglect of local issues. In 1849 he was elected Rector of the University of Glasgow, a position with no administrative duties, often awarded by the students to men of political or literary fame.[30] He also received the freedom of the city.[31]

In 1852, the voters of Edinburgh offered to re-elect him to Parliament. He accepted on the express condition that he need not campaign and would not pledge himself to a position on any political issue. Remarkably, he was elected on those terms. He seldom attended the House due to ill health. His weakness after suffering a heart attack caused him to postpone for several months making his speech of thanks to the Edinburgh voters. He resigned his seat in January 1856.[32] In 1857 he was raised to the peerage as Baron Macaulay, of Rothley in the County of Leicester,[33] but seldom attended the House of Lords.[32]

Later life (1857–1859)

Macaulay sat on the committee to decide on the historical subjects to be painted in the new Palace of Westminster.[34] The need to collect reliable portraits of notable figures from history for this project led to the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery, which was formally established on 2 December 1856.[35] Macaulay was amongst its founding trustees and is honoured with one of only three busts above the main entrance.

During his later years his health made work increasingly difficult for him. He died of a heart attack on 28 December 1859, aged 59, leaving his major work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second incomplete.[36] On 9 January 1860 he was buried in Westminster Abbey, in Poets' Corner, near a statue of Addison.[11] As he had no children, his peerage became extinct on his death.

Macaulay's nephew, Sir George Trevelyan, Bt, wrote a best-selling "Life and Letters" of his famous uncle, which is still the best complete life of Macaulay. His great-nephew was the Cambridge historian G. M. Trevelyan.

Literary works

As a young man he composed the ballads Ivry and The Armada,[37] which he later included as part of Lays of Ancient Rome, a series of very popular poems about heroic episodes in Roman history which he began composing in India and continued in Rome, finally publishing in 1842.[38] The most famous of them, Horatius, concerns the heroism of Horatius Cocles. It contains the oft-quoted lines:[39]

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods?"

His essays, originally published in the Edinburgh Review, were collected as Critical and Historical Essays in 1843.[40]

Historian

During the 1840s, Macaulay undertook his most famous work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, publishing the first two volumes in 1848. At first, he had planned to bring his history down to the reign of George III. After publication of his first two volumes, his hope was to complete his work with the death of Queen Anne in 1714.[41]

The third and fourth volumes, bringing the history to the Peace of Ryswick, were published in 1855. At his death in 1859 he was working on the fifth volume. This, bringing the History down to the death of William III, was prepared for publication by his sister, Lady Trevelyan, after his death.[42]

Political writing

Macaulay's political writings are famous for their ringing prose and for their confident, sometimes dogmatic, emphasis on a progressive model of British history, according to which the country threw off superstition, autocracy and confusion to create a balanced constitution and a forward-looking culture combined with freedom of belief and expression. This model of human progress has been called the Whig interpretation of history. This philosophy appears most clearly in the essays Macaulay wrote for the Edinburgh Review and other publications, which were collected in book form and a steady best-seller throughout the 19th century. But it is also reflected in History; the most stirring passages in the work are those that describe the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688.

Macaulay's approach has been criticised by later historians for its one-sidedness and its complacency. His tendency to see history as a drama led him to treat figures whose views he opposed as if they were villains, while characters he approved of were presented as heroes. Macaulay goes to considerable length, for example, to absolve his main hero William III of any responsibility for the Glencoe massacre. Winston Churchill devoted a four volume biography of the Duke of Marlborough to rebutting Macaulay's slights on his ancestor, expressing hope 'to fasten the label "Liar" to his genteel coat-tails.'[43]

Legacy as a historian

The Liberal historian Lord Acton read Macaulay's History of England four times and later described himself as "a raw English schoolboy, primed to the brim with Whig politics" but "not Whiggism only, but Macaulay in particular that I was so full of." However, after coming under German influence Acton would later find fault in Macaulay.[44] In 1880 Acton classed Macaulay (with Burke and Gladstone) as one "of the three greatest Liberals".[45] In 1883, he advised Mary Gladstone:

[T]he Essays are really flashy and superficial. He was not above par in literary criticism; his Indian articles will not hold water; and his two most famous reviews, on Bacon and Ranke, show his incompetence. The essays are only pleasant reading, and a key to half the prejudices of our age. It is the History (with one or two speeches) that is wonderful. He knew nothing respectably before the seventeenth century, he knew nothing of foreign history, of religion, philosophy, science, or art. His account of debates has been thrown into the shade by Ranke, his account of diplomatic affairs, by Klopp. He is, I am persuaded, grossly, basely unfair. Read him therefore to find out how it comes that the most unsympathetic of critics can think him very nearly the greatest of English writers…[46]

In 1885, Acton asserted that:

We must never judge the quality of a teaching by the quality of the Teacher, or allow the spots to shut out the sun. It would be unjust, and it would deprive us of nearly all that is great and good in this world. Let me remind you of Macaulay. He remains to me one of the greatest of all writers and masters, although I think him utterly base, contemptible and odious for certain reasons which you know.[47]

In 1888, Acton wrote that Macaulay "had done more than any writer in the literature of the world for the propagation of the Liberal faith, and he was not only the greatest, but the most representative, Englishman then living".[48]

W. S. Gilbert described Macaulay's wit, "who wrote of Queen Anne" as part of Colonel Calverley's Act I patter song in the libretto of the 1881 operetta Patience. (This line may well have been a joke about the Colonel's pseudo-intellectual bragging, as most educated Victorians knew that Macaulay did not write of Queen Anne; the History encompasses only as far as the death of William III in 1702, who was succeeded by Anne.)

Herbert Butterfield's The Whig Interpretation of History (1931) attacked Whig history. The Dutch historian Pieter Geyl, writing in 1955, considered Macaulay's Essays as "exclusively and intolerantly English".[49]

On 7 February 1954, Lord Moran, doctor to the Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, recorded in his diary:

Randolph, who is writing a life of the late Lord Derby for Longman's, brought to luncheon a young man of that name. His talk interested the P.M. ... Macaulay, Longman went on, was not read now; there was no demand for his books. The P.M. grunted that he was very sorry to hear this. Macaulay had been a great influence in his young days.[50]

George Richard Potter, Professor and Head of the Department of History at the University of Sheffield from 1931 to 1965, claimed "In an age of long letters ... Macaulay's hold their own with the best".[51] However Potter also claimed:

For all his linguistic abilities he seems never to have tried to enter into sympathetic mental contact with the classical world or with the Europe of his day. It was an insularity that was impregnable ... If his outlook was insular, however, it was surely British rather than English.[52]

With regards to Macaulay's determination to inspect physically the places mentioned in his History, Potter said:

Much of the success of the famous third chapter of the History which may be said to have introduced the study of social history, and even ... local history, was due to the intense local knowledge acquired on the spot. As a result it is a superb, living picture of Great Britain in the latter half of the seventeenth century ... No description of the relief of Londonderry in a major history of England existed before 1850; after his visit there and the narrative written round it no other account has been needed ... Scotland came fully into its own and from then until now it has been a commonplace that English history is incomprehensible without Scotland.[53]

Potter noted that Macaulay has had many critics, some of whom put forward some salient points about the deficiency of Macaulay's History but added: "The severity and the minuteness of the criticism to which the History of England has been subjected is a measure of its permanent value. It is worth every ounce of powder and shot that is fired against it." Potter concluded that "in the long roll of English historical writing from Clarendon to Trevelyan only Gibbon has surpassed him in security of reputation and certainty of immortality".[54]

Piers Brendon wrote that Macaulay is "the only British rival to Gibbon."[55] In 1972, J. R. Western wrote that: "Despite its age and blemishes, Macaulay's History of England has still to be superseded by a full-scale modern history of the period."[56] In 1974 J. P. Kenyon stated that: "As is often the case, Macaulay had it exactly right."[57]

W. A. Speck wrote in 1980, that a reason Macaulay's History of England "still commands respect is that it was based upon a prodigious amount of research".[58] Speck claimed:

Macaulay's reputation as an historian has never fully recovered from the condemnation it implicitly received in Herbert Butterfield's devastating attack on The Whig Interpretation of History. Though he was never cited by name, there can be no doubt that Macaulay answers to the charges brought against Whig historians, particularly that they study the past with reference to the present, class people in the past as those who furthered progress and those who hindered it, and judge them accordingly.[59]

According to Speck:

[Macaulay too often] denies the past has its own validity, treating it as being merely a prelude to his own age. This is especially noticeable in the third chapter of his History of England, when again and again he contrasts the backwardness of 1685 with the advances achieved by 1848. Not only does this misuse the past, it also leads him to exaggerate the differences.[59]

On the other hand, Speck also wrote that Macaulay "took pains to present the virtues even of a rogue, and he painted the virtuous warts and all",[60] and that "he was never guilty of suppressing or distorting evidence to make it support a proposition which he knew to be untrue".[61] Speck concluded:

What is in fact striking is the extent to which his History of England at least has survived subsequent research. Although it is often dismissed as inaccurate, it is hard to pinpoint a passage where he is categorically in error ... his account of events has stood up remarkably well ... His interpretation of the Glorious Revolution also remains the essential starting point for any discussion of that episode ... What has not survived, or has become subdued, is Macaulay's confident belief in progress. It was a dominant creed in the era of the Great Exhibition. But Auschwitz and Hiroshima destroyed this century's claim to moral superiority over its predecessors, while the exhaustion of natural resources raises serious doubts about the continuation even of material progress into the next.[61]

In 1981, J. W. Burrow argued that Macaulay's History of England:

... is not simply partisan; a judgement, like that of Firth, that Macaulay was always the Whig politician could hardly be more inapposite. Of course Macaulay thought that the Whigs of the seventeenth century were correct in their fundamental ideas, but the hero of the History was William, who, as Macaulay says, was certainly no Whig ... If this was Whiggism it was so only, by the mid-nineteenth century, in the most extended and inclusive sense, requiring only an acceptance of parliamentary government and a sense of gravity of precedent. Butterfield says, rightly, that in the nineteenth century the Whig view of history became the English view. The chief agent of that transformation was surely Macaulay, aided, of course, by the receding relevance of seventeenth-century conflicts to contemporary politics, as the power of the crown waned further, and the civil disabilities of Catholics and Dissenters were removed by legislation. The History is much more than the vindication of a party; it is an attempt to insinuate a view of politics, pragmatic, reverent, essentially Burkean, informed by a high, even tumid sense of the worth of public life, yet fully conscious of its interrelations with the wider progress of society; it embodies what Hallam had merely asserted, a sense of the privileged possession by Englishmen of their history, as well as of the epic dignity of government by discussion. If this was sectarian it was hardly, in any useful contemporary sense, polemically Whig; it is more like the sectarianism of English respectability.[62]

In 1982, Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote:

[M]ost professional historians have long since given up reading Macaulay, as they have given up writing the kind of history he wrote and thinking about history as he did. Yet there was a time when anyone with any pretension to cultivation read Macaulay.[63]

Himmelfarb also laments that "the history of the History is a sad testimonial to the cultural regression of our times".[64]

In the novel Marathon Man and its film adaptation, the protagonist was named 'Thomas Babington' after Macaulay.[65]

In 2008, Walter Olson argued for the pre-eminence of Macaulay as a British classical liberal.[66]

Works

- Works by Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay at Project Gutenberg

- Lays of Ancient Rome

- . Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. 1848 – via Wikisource.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- 5 vols (1848): Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3, Vol 4, Vol 5 at Internet Archive

- 5 vols (1848): Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4, Vol. 5 at Project Gutenberg

- volumes 1–3 at LibriVox.org

- Critical and Historical Essays, 2 vols, edited by Alexander James Grieve. Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- "Social and Industrial Capacities of the Negroes". Critical Historical and Miscellaneous Essays with a Memoir and Index. Vols V. and VI. Mason, Baker & Pratt. 1873.

- Lays of Ancient Rome: With Ivry, and The Armada. Longmans, Green, and Company. 1881.

- William Pitt, Earl of Chatham: Second Essay (Maynard, Merrill, & Company, 1892, 110 pages)

- The Miscellaneous Writings and Speeches of Lord Macaulay, 4 vols Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4

- Machiavelli on Niccolò Machiavelli

- The Letters of Thomas Babington Macaulay, 6 vols, edited by Thomas Pinney.

- The Journals of Thomas Babington Macaulay, 5 vols, edited by William Thomas.

- Macaulay index entry at Poets' Corner

- Lays of Ancient Rome (Complete) at Poets' Corner with an introduction by Bob Blair

- Works by Thomas Babington Macaulay at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

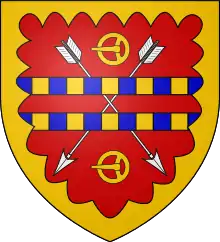

Arms

|

|

See also

- Philosophic Whigs

- Whig history further explains the interpretation of history that Macaulay espoused.

- Samuel Rogers#Middle life and friendships

References

- MacKenzie, John (January 2013), "A family empire", BBC History Magazine

- Kampfner, John (22 July 2013). "Macaulay by Zareer Masani – review". the Guardian. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- For full text of Macaulay's minute see "Minute by the Hon'ble T. B. Macaulay, dated the 2nd February 1835"

- Biographical index of former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.

- "Thomas Babbington Macaulay". Josephsmithacademy. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Symonds, P. A. "Babington, Thomas (1758–1837), of Rothley Temple, nr. Leicester". History of Parliament on-line. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- Kuper 2009, p. 146.

- Knight 1867, p. 8.

- Sullivan 2010, p. 21.

- "Macaulay, Thomas Babington (FML817TB)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Thomas, William. "Macaulay, Thomas Babington, Baron Macaulay (1800–1859), historian, essayist, and poet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17349. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Pattison 1911, p. 193.

- Rupprecht 2012, pp. 435–455.

- Macaulay 1873, p. 361, Vol. VI.

- "Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Moody: Profile and Legacies Summary". Legacies of British Slave-Ownership. University College London. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- Cropper 1864: see entry for 22 November 1831

- Sullivan 2010, p. 466.

- Galton 1869, p. 23.

- Sullivan 2010, p. 9.

- Evans 2002, p. 260.

- Spear 1938, pp. 78–101.

- ""Government of India" - A SPEECH DELIVERED IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS ON THE 10TH OF JULY 1833". www.columbia.edu. Columbia university and Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Think it Over: Macaulay and India's rootless generations

- Watt & Mann 2011, p. 23.

- Losurdo 2014, p. 250.

- Losurdo 2014, pp. 250-251.

- "No. 19774". The London Gazette. 1 October 1839. p. 1841.

- Macaulay's speeches on copyright law

- "Lord Macaulay". Bartleby. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "The Rector". Glasgow university. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "Biography of Lord Macaulay". Sacklunch. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "Lord Macaulay". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 March 1860. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "No. 22039". The London Gazette. 11 September 1857. p. 3075.

- "Thomas Babington Macaulay". Clanmacfarlanegenealogy. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "From the Director" (PDF). Face to Face. National Portrait Gallery (16). Spring 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- "Death of Lord Macaulay". The New York Times. 17 January 1960. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- Macaulay 1881.

- Sullivan, Robert E (2009). Macaulay. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 251. ISBN 9780674054691. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- "Thomas Babington Macaulay, Lord Macaulay Horatius". English verse. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Macaulay 1941, p. x.

- Macaulay 1848, Vol. V, title page and prefatory "Memoir of Lord Macaulay".

- Macaulay 1848.

- Churchill 1947, p. 132: "It is beyond our hopes to overtake Lord Macaulay. The grandeur and sweep of his story-telling carries him swiftly along, and with every generation he enters new fields. We can only hope that Truth will follow swiftly enough to fasten the label 'Liar' to his genteel coat-tails."

- Hill 2011, p. 25.

- Paul 1904, p. 57.

- Paul 1904, p. 173.

- Paul 1904, p. 210.

- Lord Acton 1919, p. 482.

- Geyl 1958, p. 30.

- Lord Moran 1968, pp. 553–554.

- Potter 1959, p. 10.

- Potter 1959, p. 25.

- Potter 1959, p. 29.

- Potter 1959, p. 35.

- Brendon 2010, p. 126.

- Western 1972, p. 403.

- Kenyon 1974, p. 47, n. 14.

- Speck 1980, p. 57.

- Speck 1980, p. 64.

- Speck 1980, p. 65.

- Speck 1980, p. 67.

- Burrow 1983.

- Himmelfarb 1986, p. 163.

- Himmelfarb 1986, p. 165.

- Goldman 1974, p. 20.

- Olson 2008, pp. 309-310.

- Burke 1864, p. 635.

Sources

- Brendon, Piers (2010). The Decline And Fall Of The British Empire. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4090-7796-1.

- Burke, Bernard (1864). The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales: Comprising a Registry of Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time. Harrison & sons.

- Burrow, J. W. (1983). A Liberal Descent: Victorian Historians and the English Past. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27482-1.

- Churchill, Winston (1947). Marlborough: His Life and Times. Volume 1. London: Geo. Harrap & Co.

- Cropper, Margaret (1864). Recollections by a sister of T.B. Macaulay.

- Evans, Stephen (2002). "Macaulay's minute revisited: Colonial language policy in nineteenth-century India". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 23 (4): 260–81. doi:10.1080/01434630208666469. S2CID 144856725.

- Galton, Francis (1869). Hereditary Genius: an Inquiry Into Its Laws and Consequences. London: Macmillan.

- Geyl, Pieter (1958). Debates with Historians. Meridian.

- Goldman, William (1974). Marathon Man. Dell. ISBN 978-0-440-05327-9.

- Gonçalves, Sérgio Campos (2010). "Thomas Babington Macaulay". In Jurandir Malerba (ed.). Lições de história : o caminho da ciência no longo século XIX. Rio de Janeiro: Editora FGV. ISBN 978-85-7430-999-6.

- Hill, Roland (2011). Lord Acton. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18127-2.

- Himmelfarb, Gertrude (1986). "Who Now Reads Macaulay?". Marriage and Morals Among The Victorians. And other Essays. London: Faber and Faber.

- Kenyon, J. P. (1974). "The Revolution of 1688: Resistance and Contract". In McKendrick, Neil (ed.). Historical Perspectives. Studies in English thought and Society in Honour of J. H. Plumb. London: Europa.

- Knight, Charles, ed. (1867). "Macaulay, Rt Hon Thomas Babington". The English Cyclopaedia : Biography; Volume IV. London: Bradbury Evans & Co. p. 8.

- Kuper, Adam (2009). Incest and Influence. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03589-8.

- Lord Acton (1919). Figgis, John Neville; Laurence, Reginald Vere (eds.). Historical Essays and Studies. London: Macmillan.

- Lord Moran (1968). Winston Churchill: the struggle for survival, 1940-1965. London: Sphere.

- Losurdo, Domenico (2014). Liberalism: A Counter-history. Verso. ISBN 978-1-78168-166-4.

- Marx, Karl Heinrich (1906). Friedrich Engels (ed.). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. New York: Modern Library.

- Olson, Walter (2008). "Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1800–1859)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n185. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- Paul, Herbert, ed. (1904). Letters of Lord Acton to Mary Gladstone. London: George Allen.

- Potter, G. R. (1959). Macaulay. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Rupprecht, Anita (September 2012). "'When he gets among his countrymen,they tell him that he is free': Slave Trade Abolition, Indentured Africans and a Royal Commission". Slavery & Abolition. 33 (3): 435–455. doi:10.1080/0144039X.2012.668300. S2CID 144301729.

- Spear, Percival (1938). "Bentinck and Education". Cambridge Historical Journal. 6 (1): 78–101. doi:10.1017/S1474691300003814. JSTOR 3020849.

- Speck, W. A. (1980). "Thomas Babington Macaulay". In Cannon, John (ed.). The Historian at Work. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Sullivan, Robert E (2010). Macaulay: The Tragedy of Power. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05469-1.

- Watt, Carey Anthony; Mann, Michael, eds. (2011). Civilizing Missions in Colonial and Postcolonial South Asia: From Improvement to Development. Anthem Press. ISBN 978-1-84331-864-4.

- Western, John R. (1972). Monarchy and revolution. Rowman & Littlefield.

Further reading

- Bryant, Arthur (1932). Macaulay (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1979). ISBN 0-297-77550-2 [Facsimile reprint of London, P. Davies], old, popular biography.

- Clive, John Leonard (1973). Thomas Babington Macaulay: The Shaping of the Historian London: Secker and Warburg. ISBN 0-436-10220-X.

- Cruikshank, Margaret (1978). Thomas Babington Macaulay. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-6686-3.

- Edwards, Owen Dudley (1988). Macaulay. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Hall, Catherine (2009). "Macaulay's Nation". Victorian Studies. 51 (3): 505–523. doi:10.2979/vic.2009.51.3.505. S2CID 145678995.

- Harrington, Jack (2010). Sir John Malcolm and the Creation of British India, Ch. 6. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-10885-1.

- Howard, Michael. "Historians Reconsidered : II Macaulay." History Today (May 1951) 1#5 pp 56–61 online.

- Jann, Rosemary The Art and Science of Victorian History (1985) online free

- Masani, Zareer (2013). Macaulay: Britain's Liberal Imperialist. London: Bodley Head.

- Trevelyan, Sir George Otto (1909). The Life and Letters of Lord Macaulay. Volume 1. Harper and Brothers.

- Pattison, Mark (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 193–196.

- Speck, W. A., 'Robert Southey, Lord Macaulay and the Standard of Living Controversy', History 86 (2001) 467–477 <doi:10.1111/1468-229x.00201>.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay. |

- Portraits of Thomas Babington Macaulay at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800–1859), Fran Pritchett, Columbia University

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Thomas Babington Macaulay

- Works by Thomas Babington Macaulay at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Babington Macaulay at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Babington Macaulay at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- books by Macauly at Readanybook.com

- Lord Macaulay's Habit of Exaggeration, JamesBoswell.info

- Macaulay's Minute revisited, Ramachandra Guha, The Hindu, 4 February 2007

- Thomas Babington Macaulay at Find a Grave

- Thomas Babington Macaulay at Find a Grave (memorial statue, antechapel, Trinity College, Cambridge, UK)

- Thomas Babington Macaulay at Curlie

.svg.png.webp)