Vajrayogini

Vajrayoginī (Sanskrit: Vajrayoginī; Tibetan: རྡོ་རྗེ་རྣལ་འབྱོར་མ་, Wylie: rdo rje rnal ’byor ma , Dorjé Neljorma; Mongolian: Огторгуйд Одогч, Нархажид, Chinese: 金刚瑜伽母; pinyin: Jīngāng Yújiāmǔ) is a Tantric Buddhist female Buddha and a ḍākiṇī. Vajrayoginī's essence is "great passion" (maharaga), a transcendent passion that is free of selfishness and illusion — she intensely works for the well-being of others and for the destruction of ego clinging. She is seen as being ideally suited for people with strong passions, providing the way to transform those passions into enlightened virtues.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

She is an Anuttarayoga Tantra iṣṭadevatā (meditation deity) and her practice includes methods for preventing ordinary death, intermediate state (bardo) and rebirth (by transforming them into paths to enlightenment), and for transforming all mundane daily experiences into higher spiritual paths.[2] Practices associated with her are Chöd and the Six Yogas of Naropa.

Vajrayoginī is often described with the epithet sarvabuddhaḍākiṇī, meaning "the ḍākiṇī [who is the Essence] of all Buddhas".[3]

Origin and lineage

Vajrayoginī's sādhanā originated in Nepal between the tenth and twelfth centuries. It evolved from the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra, where Vajrayoginī appears as his Yab-Yum consort,[4][5] to become a stand-alone practice of Anuttarayoga Tantra in its own right.[6] The practice of Vajrayoginī belongs to the Mother Tantra (Wylie: ma rgyud ) class of Anuttarayoga Tantras along with other tantras such as the Cakrasaṃvara and Hevajra Tantras.

Vajrayana teaches that the two stages of the practice of Vajrayoginī (generation stage and completion stage) were originally taught by Vajradhara. He manifested in the form of Heruka to expound the Root Tantra of Chakrasaṃvara, and it was in this tantra that he explained the practice of Vajrayoginī. All the many lineages of instructions on Vajrayoginī can be traced back to this original revelation. Of these lineages, there are three that are most commonly practiced: the Narokhachö lineage, which was transmitted from Vajrayoginī to Naropa; the Maitrikhachö lineage, which was transmitted from Vajrayoginī to Maitripa; and the Indrakhachö lineage, which was transmitted from Vajrayoginī to Indrabodhi.[7]

Iconography

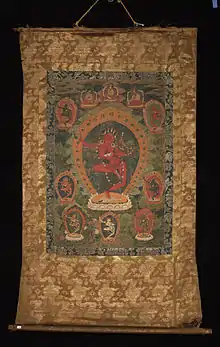

Vajrayoginī is visualized as the translucent, deep red form of a 16-year-old female with the third eye of wisdom set vertically on her forehead and unbound flowing hair. Vajrayoginī is generally depicted with the traditional accoutrements of a ḍākiṇī, including a kartika (a vajra-handled flaying knife ) in her right hand and a kapala filled with blood in her left hand that she drinks from with upturned mouth. Her consort Cakrasaṃvara is often symbolically depicted as a khaṭvāṅga on Vajrayoginī's left shoulder, when she is in "solitary hero" form. Vajrayoginī's khaṭvāṅga is marked with a vajra and from it hangs a damaru drum, a bell, and a triple banner. Her extended right leg treads on the chest of red Kālarātri, while her bent left leg treads on the forehead of black Bhairava, bending his head backward and pressing it into his back at the level of his heart. Her head is adorned with a crown of five human skulls and she wears a necklace of fifty human skulls. She is depicted as standing in the center of a blazing fire of exalted wisdom. Her countenance shows both erotic and fierce features, "in the fullness of bliss, laughing and baring her fangs."[8]

Each aspect of Vajrayoginī's form and mandala is designed to convey a spiritual meaning. For example, her brilliant red-colored body symbolizes the blazing of her tummo (candali) or "inner fire" of spiritual transformation as well as life force (Shakti), blood of birth and menstrual blood.[9] Her single face symbolizes that she has realized that all phenomena are of one nature in emptiness. Her two arms symbolize her realization of the two truths. Her three eyes symbolize her ability to see everything in the past, present and future. She looks upward toward the Pure Dākiṇī Land, demonstrating her attainment of outer and inner Pure Dākiṇī Land, and indicating that she leads her followers to these attainments. The curved driguk knife in her right hand shows her power to cut the continuum of the delusions and obstacles of her followers and of all living beings. Drinking the blood from the kapala in her left hand symbolizes her experience of the clear light of bliss.[10]

Vajravārāhī and other forms

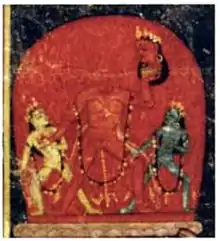

Vajrayoginī is a female deity and although she is sometimes visualized as simply Vajrayoginī, in a collection of her sādhanās she is visualized in an alternate form in over two thirds of the practices.[11] Her other forms include Vajravārāhī (Wylie: rdo-rje phag-mo "Vajra Sow") and Krodikali (alt. Krodhakali, Kālikā, Krodheśvarī, Krishna Krodhini, Tibetan Tröma Nakmo; Wylie: khros ma nag mo , "Wrathful Lady", "Fierce Black One").[12][13]

In her form as Vajravārāhī "the Vajra Sow", she is often pictured with a sow's head on the side of her own as an ornament and in one form has the head of a sow herself. Vajrayoginī is often associated with triumph over ignorance, the pig being associated with ignorance in Buddhism. This sow head relates to the origins of Vajravārāhī from the Hindu sow-faced goddess Vārāhī.[14]

The severed-headed form of Vajrayoginī is similar to the Indian goddess Chinnamasta, who is recognized by both Hindus and Buddhists.[15]

A white manifestation, generally designated as Prajñaloka, “Light of Wisdom ,” displays a vajra and a skull bowl.

Practices

Vajrayoginī acts as a meditation deity, or the yab-yum consort of such a deity, in Vajrayāna Buddhism. She appears in a maṇḍala that is visualized by the practitioner according to a sādhana describing the practice of the particular tantra. There are several collections containing sādhanas associated with Vajrayoginī including one collection, the Guhyasamayasādhanamālā, containing only Vajrayoginī sādhanas and comprising forty-six works by various authors.

The yidam that a meditator identifies with when practicing the Six Yogas of Nāropa is Vajrayoginī and she is an important deity for tantric initiation, especially for new initiates as Vajrayoginī's practice is said to be well-suited to those with strong desirous attachment, and to those living in the current "degenerate age". As Vajravārāhī, her consort is Chakrasaṃvara (Tib. Khorlo Demchog), who is often depicted symbolically as a khaṭvāṇga on her left shoulder. In this form she is also the consort of Jinasagara (Tib. Gyalwa Gyatso), the red Avalokiteśvara (Tib. Chenrezig).

Vajrayoginī is a key figure in the advanced Tibetan Buddhist practice of Chöd, where she appears in her Kālikā (Standard Tibetan: Khros ma nag mo) or Vajravārāhī (Tibetan:rDo rje phag mo) forms.

Vajrayoginī also appears in versions of Guru yoga in the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. In one popular system the practitioner worships their guru in the form of Milarepa, whilst visualizing themself as Vajrayoginī.[16]

The purpose of visualizing Vajrayoginī is to gain realizations of generation stage tantra, in which the practitioner mentally visualises themself as their yidam or meditational deity and their surroundings as the Deity's maṇḍala. The purpose of generation stage is to overcome so-called ordinary appearances and ordinary conceptions, which are said in Vajrayana Buddhism to be the obstructions to liberation (Skt. nirvāṇa) and enlightenment.[17]

According to most commentaries associated with the deity, the practices of Vajrayoginī are relatively easy compared to those of other Highest Yoga Tantra yidams and particularly suited to practitioners in modern times:....

The instructions on the practice of Vajrayoginī contain concise and clearly presented meditations that are relatively easy to practice. The mantra is short and easy to recite, and the visualizations of the maṇḍala, the Deity, and the body maṇḍala are simple compared with those of other Highest Yoga Tantra Deities. Even practitioners with limited abilities and little wisdom can engage in these practices without great difficulty. The practice of Vajrayoginī quickly brings blessings, especially during this spiritually degenerate age. It is said that as the general level of spirituality decreases, it becomes increasingly difficult for practitioners to receive the blessings of other Deities; but the opposite is the case with Heruka and Vajrayoginī – the more times degenerate, the more easily practitioners can receive their blessings.[18]

Vajrayogini Temples

In the Kathmandu valley of Nepal there are several important Newar temples dedicated to different forms of Vajrayogini. These temples are important power places of Nepalese Vajrayana Buddhism[19] and are also important pilgrimage places for Tibetan Buddhists. These temples include the Sankhu Vajrayogini temple, Vidhyeshvari Vajrayogini temple, Parping Vajrayogini temple, and the Guhyeshwari temple.

Emanations

Samding Dorje Phagmo

The female tulku who was the abbess of Samding Monastery, on the shores of the Yamdrok Tso Lake, near Gyantse, Tibet was traditionally a nirmāṇakāya emanation of Vajravārāhī (Tibetan: Dorje Phagmo).[20] The lineage started in the 15th century with the princess of Gungthang, Chökyi Drönma (Wylie: Chos-kyi sgron-me)(1422–1455).[21] She became known as Samding Dorje Pagmo (Wylie:bSam-lding rDo-rje phag-mo) and began a line of female tulkus, reincarnate lamas. Charles Alfred Bell met the tulku in 1920 and took photographs of her, calling her Dorje Pamo in his book.[22][23] The current incarnation, the 12th of this line,[24] resides in Lhasa,[25] where she is known as Female Living Buddha Dorje Palma by the Chinese.[26]

References

- Shaw, Miranda (2006). Buddhist Goddesses of India. USA: Princeton University Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-691-12758-3.

- Guide to Dakini Land page xii, a commentary to Illuminating All Hidden Meanings (Wylie: be don kun sal ) by Je Tsongkhapa.

- Vajrayogini - Buddhist Tantric Practice Support (see #General characteristics) from StudyBuddhism.com

- "Large Size Paramasukha-Chakrasamvara and Vajravarahi".

- "Shamvara and Vajravarahi in Yab Yum".

- English, Elizabeth (2002). Vajrayoginī: Her Visualizations, Rituals, & Forms. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-329-X

- Gyatso, Geshe Kelsang (1996). Guide to Dakini land : the highest yoga tantra practice of Buddha Vajrayogini (2nd ed. rev. ed.). London: Tharpa. ISBN 978-0-948006-39-5.

- Shaw, Miranda, Buddhist Goddesses of India, page 361

- Shaw, Miranda, Buddhist Goddesses of India, page 361

- Guide to Dakini Land: The Highest Yoga Tantra Practice of Buddha Vajrayogini, pages page 123-127, Tharpa Publications (2nd. ed., 1996), Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, ISBN 978-0-948006-39-5

- English, Elizabeth (2002). Vajrayoginī: Her Visualizations, Rituals and Forms. Wisdom Publications. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-86171-329-5.

- The Forms of Vajrayoginī Himalayan Art Resources

- "Vajrayogini (Buddhist Deity) - Krodha Kali (Wrathful Black Varahi) (HimalayanArt)".

- English, Elizabeth (15 June 2002). "The Emergence of Vajrayogini". Vajrayoginī: her visualizations, rituals, & forms. Wisdom Publications. pp. 47–9. ISBN 978-0-86171-329-5.

- Bernard, Elizabeth Anne (2000). Chinnamasta: The Awful Buddhist and Hindu Tantric Goddess. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1748-7.

- English, Elizabeth (2002). Vajrayogini: Her Visualizations, Rituals and Forms. Wisdom Publications. p. xxiii. ISBN 978-0-86171-329-5.

- Guide to Dakini Land: The Highest Yoga Tantra Practice of Buddha Vajrayogini, pages 154-5, Tharpa Publications (2nd. ed., 1996), Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, ISBN 978-0-948006-39-5

- Guide to Dakini Land: The Highest Yoga Tantra Practice of Buddha Vajrayogini, pages 5 - 10, Tharpa Publications (2nd. ed., 1996), Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, ISBN 978-0-948006-39-5

- Shakya, Min Bahadur (1994). The Iconography of Nepalese Buddhism. Kathmandu: Handicraft Association of Nepal.

- Tashi Tsering, A Preliminary Reconstruction of the Successive Reincarnations of Samding Dorje Phagmo; The Foremost Woman Incarnation of Tibet , Youmtsho - Journal of Tibetan Women's Studies, no. 1, pp.20-53

- "When a woman becomes a dynasty: the Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- Dorje Pamo at Samding Monastery - November 1920

- "Table of contents for When a woman becomes a dynasty".

- "A Summary Report of the 2007 International Congress on the Women's Role in the Sangha: Bhikshuni Vinaya and Ordination Lineages – Part Three: Day Two".

- Pamela Logan, Tulkus in Tibet, Harvard Asia Quarterly, Vol. VIII, No. 1. Winter 2004.

- - Yamzhog Yumco Lake guide Selected from China's Tibetby Samxuba Gonjor Yundain

Further reading

- English, Elizabeth (2002). Vajrayogini: Her Visualizations, Rituals, & Forms. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-329-X

- Tharchin, Sermey Khensur Lobsang (1997). Sublime Path to Kechara Paradise. Mahayana Sutra and Tantra Press. ISBN 0-918753-13-9

- Diemberger, Hildegard (2007): When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty - The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet, Columbia University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-231-14320-6, ISBN 9780231143202