West Indian Americans

West Indian Americans or Caribbean Americans are Americans who can trace their ancestry to the Caribbean, unless they are of native descent. As of 2016, about 13 million — about 4% of the total U.S. population — have Caribbean ancestry.[2]

| Year | Number |

|---|---|

| 1960 | 193,922 |

| 1970 | 675,108 |

| 1980 | 1,258,363 |

| 1990 | 1,938,348 |

| 2000 | 2,953,066 |

| 2009 | 3,465,890 |

The Caribbean is the source of the United States' earliest and largest Black immigrant group and the primary source of growth of the Black population in the U.S. The region has exported more of its people than any other region of the world since the abolition of slavery in 1834.[3]

The largest Caribbean immigrant sources to the U.S. are Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago and Haiti. U.S. citizens from Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands also migrate to the US proper (known as Stateside Puerto Ricans and Stateside Virgin Islands Americans, respectively).

Caribbean immigration to the United States

17th to mid-19th century

In 1613, Juan (Jan) Rodriguez from Santo Domingo became the first non-indigenous person to settle in what was then known as New Amsterdam.

The West Indian migration to the modern United States began in the colonial period, when many West Indians were imported as slaves to the British colonies of North America.

First people from West Indies who arrived in the United States were slaves brought to South Carolina in the 17th century.[3] These slaves, many of whom were born in Africa, number among the first people of African origin imported to the British colonies of North America. Over time, Barbadian slaves would make up a significant part of the Black population in Virginia, mainly in the Virginia tidewater region of the Chesapeake Bay. The number of enslaved Africans bought from the Caribbean increased in the 18th century, as the British colonies of Southeast of North America (part of the modern United States) broadened its commercial ties with other Caribbean islands.

Caribbean slaves were more numerous than those from Africa in places such as New York, which was the main slave enclave in the northeastern of the modern-day United States. The number of enslaved Africans imported from the Caribbean decreased after the New York Slave Revolt of 1712, as many white colonists blamed the incident on slaves recently arrived from the Caribbean. Between 1715 and 1741 most of the slaves of the colony remained from the West Antilles (hailing from Jamaica, Barbados and Antigua). After the New York slave revolt of 1741, slaves imported from the Caribbean were severely curtailed, and most enslaved Africans were brought directly from Africa.

Although migration from the West Indies to the United States was not very important in the first years of 19th century, it grew considerably after the end of the American Civil War in 1865, which brought about the abolition of slavery. Most of them were fleeing from poverty and certain natural phenomena (hurricanes, droughts and floods). So, the West Indians that lived in the United States increased from only 4,000 people in 1850 to more than 20,000 in 1900, while in 1930 there were already almost 100,000 people from the region living in the United States.[4]

In the 19th century the U.S. attracted many Caribbean craftsmen, scholars, teachers, preachers, doctors, inventors, clergy, (the Barbadian Joseph Sandiford Atwell was the first black man after the Civil War to be ordained in the Episcopal Church),[5] comedians (as the Bahamian Bert Williams), politicians (as Robert Brown Elliott, U.S Congressman and Attorney General of South Carolina), poets, songwriters, and activists (as the brothers James Weldon and John Rosamond Johnson). From the end of the 19th century up to 1905, most West Indian people emigrated to South Florida, New York and Massachusetts. However, shortly after, New York would become the main destination for the West Indian immigrants.[3]

About half of the population of the New Orleans area have at least distant partial Haitian ancestry originating from a migration wave before and after the Haitian revolution from the late 1700s up until 1850, of many mixed people, black African slaves and their white French slave masters, and later free black people. Haitians had an impact on the Louisiana Voodoo religion and the Louisiana Creole language. Before 1900, Haitians had the biggest impact of any Caribbean group on the United States. The Haitian Revolution itself resulted in France selling a large swath of land (Louisiana Purchase) to the United States.

World War II through the 21st century

The Caribbean migration grew during the first thirty years of the 20th century and by 1930 there were already almost 100,000 West Indian people living in the United States. At this time, they were the majority of black people migrating to the United States.[4] The migration from the West Indies became noticeable from the 1940s, with the arrived of 50,000 people from the region, both black and white. When the war came to an end, American companies hired thousands of Caribbean people, which were known as “W2 workers”.[4][3]

The companies that hired them were distributed across 1,500 municipalities and 36 US states. Most of the W2 workers worked in the rural areas, especially in Florida, where they were dedicated to the cultivation of sugar cane. However, many of these companies offered depressing working and economic conditions for their new workers. Because of that, many Caribbean workers promoted revolts (even though labor strikes were prohibited in some of these companies) or fled their respective companies in search of jobs with better conditions elsewhere.[4][3]

Most of the Caribbean, Central America and South America historically have had little tradition of immigration to America before the 1960s. Post 1965, numerous Caribbean farmers migrated to the United States. This was due to the loss of employment in the Caribbean, when the Caribbean replaced agriculture as its main source of income with the tourism and urban sector. Proximity to the U.S., fluency in English and Civil Rights legislation were reasons for the disproportionate numbers of Caribbean outflows.[3]

"The influx of direct, capital-intensive and labor-intensive foreign investment" has significantly increased Caribbean migration to the US and other countries.[3]

Today, there is a fourth wave of Caribbean migration in United States.[4] The number of Caribbean immigrants raised substantially from 193,922 in 1960 to 2 million in 2009.[6]

Demography

The majority of Hispanic/Latino Caribbeans are of mixed-race ancestry (Mulatto/Tri-racial), usually having a near even mix of white Spanish, black West African and native Caribbean Taino. Though, African ancestry is slightly stronger among Dominican multiracials, while among Puerto Rican and Cuban multiracials European ancestry is slightly stronger. Many of these European-dominant multiracials in Puerto Rico and Cuba self identify solely as "white" for historical reasons, however when they arrive to the US mainland many of them often start to see race differently. There is also significant numbers of actual whites and blacks among these groups.

The vast majority of non-Hispanic West Indian Americans are of African Afro-Caribbean descent, with the remaining portion mainly multi-racial and Indo-Caribbean people, especially in the Guyanese, Trinidadian and Surinamese communities, where people of Indo-Caribbean descent make up a significant portion of the population. The overwhelming majority of the population of Jamaica, Haiti, the Bahamas, and the island-nations in the Lesser Antilles is of purely African descent. People from Haiti are genetically and culturally the most African people outside of Africa, with almost no non-African admixture in the gene pool of the average Haitian and the most African influenced culture of any country outside of Africa.[6]

Over 70 percent of Caribbean immigrants were from Jamaica and Haiti, as of 2010. Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, Belize, the Bahamas, Barbados and Grenada, among others, also have significant immigrant populations within the United States. Though sometimes divided by language, West Indian Americans share a common Caribbean culture. Of the Hispanic population, the Puerto Rican, Dominican, Nicaraguan, Honduran, Panamanian, Cuban and Costa Rican populations are the most culturally similar to the non-Hispanic West Indian community.[7]

Many black Afro-Latinos in the Spanish-speaking countries of Central America often have cultures that resemble the English Caribbean, due to various historical events, such as Caribbean coastal areas of these countries originally being English colonies and after these countries were established there was migration from the English Caribbean to the Caribbean coast of Central America. This is especially true of the blacks in Panama, this is because at least half of them are descended from Jamaican immigrants who came to Panama in the early 1900s, many are bilingual in Spanish and English, and considered themselves to be West Indian as well.

Caribbean American communities

| Country/region of ancestry | Caribbean American population (2016 Census)[8] |

|---|---|

| 5,588,664[9] | |

| 2,315,863[10] | |

| 2,081,419[11][12][13] | |

| 1,132,460 | |

| 1,049,779 | |

| 243,498 | |

| 227,523 | |

| 103,244 | |

| 71,482 | |

| 62,369 | |

| 55,637 | |

| 42,808 | |

| 25,924 | |

| 15,199 | |

| 20,375 | |

| 13,547 | |

| 10,364 | |

| 6,368 | |

| 6,071 | |

| 5,823 | |

| 2,833 | |

| 1,970 | |

| 1,915 | |

| 1,128 | |

| 352 | |

| About | 13 million |

Locations

In Florida 549,722 West Indians (excluding Hispanic origin groups) were foreign born as of 2016. Florida had the largest number of resident West Indian(excluding Hispanic origin groups) immigrants in 2016, followed by New York with 490,826 according to the US census.

As of 2016, 9.8% (4,286,266) of the total foreign born residence in the United States was born in the Caribbean.[14]

Parts of Florida and New York, as well as numerous areas throughout the entire New England region are the only areas where blacks of recent Caribbean origin outnumber blacks of multi-generational American origin. Miami, New York City, Boston and Orlando have the highest percentages of non-Hispanic West Indian-Americans, and are also the only major cities where blacks of Caribbean origin outnumber those of multigenerational American origin. Areas in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Georgia do have significant and growing West Indian communities but are heavily overshadowed by much larger populations of native-born American Blacks.

Of the 2 groups who make up majority of West Indian Americans of non-Hispanic origin, Haitians are more likely to move to a area with a large overall Caribbean populations, while Jamaicans are more spread out and more likely to be found in cities with small Caribbean communities. Caribbean populations in Florida and New England are diverse but more Haitian-dominated, while Caribbean populations in the NYC-Philly-DC area are diverse but more Jamaican-dominated.

In 2016, 18%(3,750,000) of Florida's population reported ancestry from the Caribbean.

| State/territory | Non-Hispanic West Indian-American population (2010 Census)[15][16] | Percentage[note 1][16] |

|---|---|---|

| 8,850 | 0.1 | |

| 1,195 | 0.1 | |

| 7,676 | 0.1 | |

| 5,499 | 0.2 | |

| 76,968 | 0.2 | |

| 7,076 | 0.1 | |

| 87,149 | 2.4 | |

| 6,454 | 0.8 | |

| 7,785 | 1.2 | |

| 927,031 | 4.5 | |

| 128,599 | 1.25 | |

| 2,816 | 0.2 | |

| 694 | 0.0 | |

| 27,038 | 0.2 | |

| 7,420 | 0.1 | |

| 1,710 | 0.0 | |

| 2,775 | 0.0 | |

| 5,407 | 0.1 | |

| 7,290 | 0.1 | |

| 2,023 | 0.1 | |

| 62,358 | 1.0 | |

| 123,226 | 1.9 | |

| 15,482 | 0.1 | |

| 6,034 | 0.1 | |

| 1,889 | 0.0 | |

| 6,509 | 0.1 | |

| 593 | 0.0 | |

| 1,629 | 0.0 | |

| 5,967 | 0.2 | |

| 2,766 | 0.2 | |

| 141,828 | 1.6 | |

| 2,869 | 0.1 | |

| 844,064 | 4.3 | |

| 32,283 | 0.3 | |

| 377 | 0.0 | |

| 14,844 | 0.1 | |

| 21,187 | 0.5 | |

| 3,896 | 0.1 | |

| 74,799 | 0.6 | |

| 6,880 | 0.7 | |

| 10,865 | 0.2 | |

| 474 | 0.0 | |

| 6,130 | 0.0 | |

| 70,000 | 0.2 | |

| 1,675 | 0.0 | |

| 375 | 0.0 | |

| 40,172 | 0.5 | |

| 8,766 | 0.1 | |

| 1,555 | 0.0 | |

| 5,623 | 0.0 | |

| 526 | 0.0 | |

| USA | 4 million | 1.3% |

U.S. Counties with largest non-Latino Caribbean American populations in 2016

- Kings County, New York 305,950 (11.6%)

- Broward County, Florida 277,646 (14.5%)

- Miami-Dade County, Florida 184,393 (6.8%)

- Queens County, New York 166,952 (7.2%)

- Palm Beach County, Florida 126,020 (8.7%)

- Bronx County, New York 115,348 (7.9%)

Language

More than half of Caribbean immigrants either spoke only English or spoke English "very well." In 2009, 33.0 percent of Caribbean immigrants reported speaking only English and 23.9 percent reported speaking English "very well." In contrast, 42.8 percent of Caribbean immigrants were limited English proficient (LEP), meaning they reported speaking English less than "very well." Within this group, 9.7 percent reported that they did not speak English at all, 16.5 percent reported speaking English "well," and 16.7 percent reported speaking English "but not well."[7]

Occupations

According to the US census for 2016. West Indian Americans of the civilian employed population 16 years and over were 1,549,890. 32.6% were employed in Management, business, science, and arts occupations, 28.5% in Service occupations, 22.2% in Sales and office occupations, 6.1% in Natural resources, construction, and maintenance occupations, and 10.5% in Production, transportation, and material moving occupations.[17]

Income

As of 2017 West Indian Americans are estimated to have a median household income of $54,033. West Indians also have a median family income of $62,867. Married-couple family: $80,626, Male householder, no spouse present, family: $53,101, Female householder, no husband present, family: $43,929. Their Individual per capita income (dollars) was $26,033.[18]

Education attainment

As of 2017, 27.1 percent of West Indian Americans 25 years and over have a bachelor's degree or higher. Male, bachelor's degree or higher was 23.1% and Female, bachelor's degree or higher was 30.3%.[18]

Related ethnic groups and topics

Contributions to American culture

There are close to 50 Caribbean carnivals throughout North America that attest to the permanence of the Caribbean immigration experience. The Caribbean people brought music, such as bachata, cadence rampa, calypso, chutney, compas (kompa), cumbia, dancehall, filmi, Latin trap, méringue, merengue, parang, ragga, rapso, reggae, reggaeton, salsa, ska, soca and zouk, which has a profound impact on U.S. popular culture. Caribbean Americans also strongly influenced Hip Hop music and culture in New York City.[19][20][21] Cultural expressions and the prominence of first-and second-generation Caribbean figures in U.S. labor and grassroots politics for many decades also testify to the long tradition and established presence.[3]

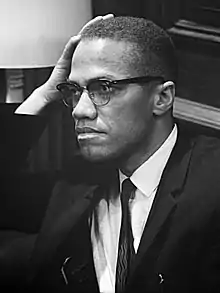

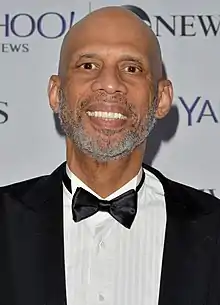

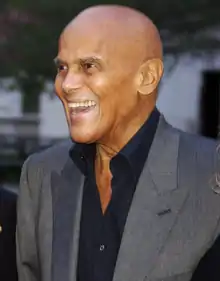

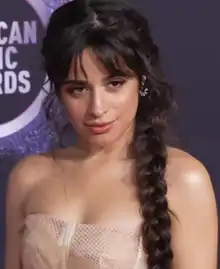

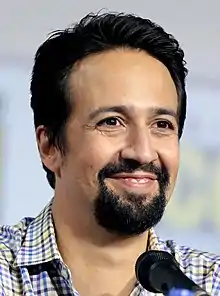

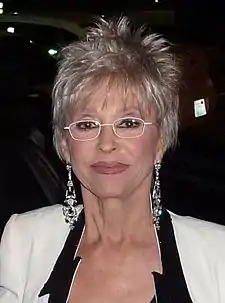

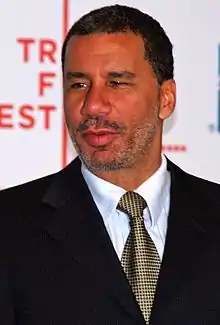

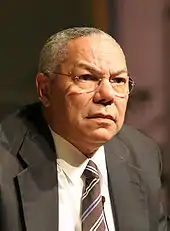

Notable Caribbean Americans and Americans of Caribbean descent

National Caribbean American Heritage Month

National Caribbean American Heritage Month is celebrated in June. The heritage month was first officially observed in 2006, after being unanimously adopted by the House of Representatives on June 27, 2005 in H. Con. Res. 71, sponsored by Congresswoman Barbara Lee, recognizing the significance of Caribbean people and their descendants in the history and culture of the United States.[22] The Senate adopted the resolution on February 14, 2006, which was introduced by Senator Chuck Schumer of New York. On June 5, 2006, George W. Bush issued a presidential proclamation declaring than June be annually recognized as National Caribbean American Heritage Month to celebrate the contributions of Caribbean Americans (both naturalized and US citizens by birth) in the United States.[23] Since the declaration, the White House has issued an annual proclamation recognizing June as National Caribbean-American Heritage Month.[24]

The Institute of Caribbean Studies based in Washington DC is the lead organization behind the Campaign which led to the establishment of Caribbean American Heritage Month.

See also

Further reading

- Black Identities: West Indian Immigrant Dreams, by Mary C. Waters

Notes

- Percentage of the state population that identifies itself as West Indian relative to the state/territory population as a whole.

References

- "Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-born Population of the United States: 1850-1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- "United States - Selected Population Profile in the United States (West Indian (excluding Hispanic origin groups) (300-359))". 2008 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2010-03-18.

- Fraizer, Martin. "Continuity and change in Caribbean immigration". People's World. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Caribbean Migration - AAME - In Motion: The African-American.

- Dickerson, Dennis C. "Joseph Sandiford Atwell (1831–1881)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- US in Foco: Caribbean Immigrants in the United States. Posted by Kristen McCabe, from Migration Policy Institute, in April 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

- McCabe, Kristine. "Caribbean Immigrants in the United States". Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- "Table 1. First, Second, and Total Responses to the Ancestry Question by Detailed Ancestry Code: 2000". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- US Census Bureau 2017 American Community Survey B03001 1-Year Estimates HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN retrieved September 25, 2018.

- US Census Bureau 2017 American Community Survey B03001 1-Year Estimates HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today retrieved September 23, 2018.

- "Table". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-14. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder - Results". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- U.S. Census Bureau 2015 American Community Survey B03001 1-Year Estimates HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today, Factfinder.census.gov, retrieved September 20, 2013

- "Place of Birth for the Foreign-born Population in the United States", Census Reporter.

- "2010 Census". Medgar Evers College. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- US Census Bureau: Table QT-P10 Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010 retrieved January 22, 2012 - select state from drop-down menu

- "SELECTED POPULATION PROFILE IN THE UNITED STATES | 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates" Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today, United States Census.

- "Table". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-14. Retrieved 2019-10-24.

- https://www.nwfolklife.org/reggae-rising-hip-hops-roots-in-reggae-music/

- https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/luttonprojects15/music-and-art/music/hip-hop/hip-hop-caribbean-origins/

- https://www.revolt.tv/2018/6/22/20825034/a-look-at-reggae-s-undoubtable-influence-on-hip-hop

- Congress (2010-07-16). Congressional Record (Bound Volumes). Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780160861550.

- Lorick-Wilmot, Yndia S. (2017-08-29). Stories of Identity among Black, Middle Class, Second Generation Caribbeans: We, Too, Sing America. Springer. ISBN 9783319622088.

- "June is Caribbean-American Heritage Month! | NRCS Caribbean Area". www.nrcs.usda.gov. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2017-12-14.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

-2_(48696671561)_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)