French Americans

French Americans or Franco-Americans (French: Franco-Américains), are citizens or nationals of the United States who identify themselves with having full or partial French or French Canadian heritage, ethnicity and/or ancestral ties.[2][3][4] On the French-Canadians see French Canadian Americans.

Franco-American Flag | |

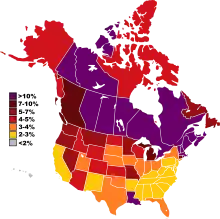

French Americans and French Canadians as percent of population by state and province.[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 10,329,465[1] ~3% of the U.S. population (2013) 8,228,623 (only French) 2,100,842 (French Canadian) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Predominantly in New England and Louisiana with smaller communities elsewhere in the contiguous United States | |

| Languages | |

| French | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic, minority Protestant | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| French Canadians, French Canadian Americans |

The state with the largest proportion of people identifying as having French ancestry is Maine, while the state with the largest number of people with French ancestry is California. Many U.S. cities have large French American populations. The city with the largest concentration of people of French extraction is Madawaska, Maine, while the largest French-speaking population by percentage of speakers in the U.S. is found in St. Martin Parish, Louisiana.

Country-wide, there are about 10.4 million U.S. residents who declare French ancestry[1] or French Canadian descent, and about 1.32 million[5] speak French at home as of 2010 census.[6][7] An additional 750,000 U.S. residents speak a French-based creole language, according to the 2011 American Community Survey.[8]

While Americans of French descent make up a substantial percentage of the American population, Franco-Americans are less visible than other similarly sized ethnic groups. This is in part due to the tendency of Franco-American groups to identify more closely with North American regional identities such as French Canadian, Acadian, Brayon, Cajuns or Louisiana Creole than as a coherent group. This has inhibited the development of a unified French American identity as is the case with other European Americans ethnic groups.

History

Some Franco-Americans arrived prior to the founding of the United States, settling in places like the Midwest, Louisiana or Northern New England. In these same areas, many cities and geographic features retain their names given by the first Franco-American inhabitants, and in sum, 23 of the Contiguous United States were colonized in part by French pioneers or French Canadians, including settlements such as Iowa (Des Moines), Missouri (St. Louis), Kentucky (Louisville) and Michigan (Detroit), among others.[9] While found throughout the country, today Franco-Americans are most numerous in New England, northern New York, the Midwest and Louisiana. Often, Franco-Americans are identified more specifically as being of French Canadians, Cajuns or Louisiana Creole descent.[10]

A vital segment of Franco-American history involves the Quebec diaspora of the 1840s–1930s, in which nearly one million French Canadians moved to the United States, mainly relocating to New England mill towns, fleeing economic downturn in Québec and seeking manufacturing jobs in the United States. Historically, French Canadians had among the highest birth rates in world history, explaining their relatively large population despite low immigration rates from France. These immigrants mainly settled in Québec and Acadia, although some eventually inhabited Ontario and Manitoba. Many of the first French-Canadian migrants to the U.S. worked in the New England lumber industry, and, to a lesser degree, in the burgeoning mining industry in the upper Great Lakes. This initial wave of seasonal migration was then followed by more permanent relocation in the United States by French-Canadian millworkers.

Louisiana

Louisiana Creole people refers to those who are descended from the colonial settlers in Louisiana, especially those of French and Spanish descent. The term is now commonly applied to individuals of mixed-race heritage. Both groups have common European heritage and share cultural ties, such as the traditional use of the French language and the continuing practice of Catholicism; in most cases, the people are related to each other. Those of mixed race also sometimes have African and Native American ancestry.[11] As a group, the mixed-race Creoles rapidly began to acquire education, skills (many in New Orleans worked as craftsmen and artisans), businesses and property. They were overwhelmingly Catholic, spoke Colonial French (although some also spoke Louisiana Creole French) and kept up many French social customs, modified by other parts of their ancestry and Louisiana culture. The free people of color married among themselves to maintain their class and social culture. The French-speaking mixed-race population came to be called "Creoles of color".

The Cajuns of Louisiana have a unique heritage. Their ancestors settled Acadia, in what is now the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and part of Maine in the 17th and early 18th centuries. In 1755, after capturing Fort Beauséjour in the region, the British Army forced the Acadians to either swear an oath of loyalty to the British Crown or face expulsion. Thousands refused to take the oath, causing them to be sent, penniless, to the 13 colonies to the south in what has become known as the Great Upheaval. Over the next generation, some four thousand managed to make the long trek to Louisiana, where they began a new life. The name Cajun is a corruption of the word Acadian. Many still live in what is known as the Cajun Country, where much of their colonial culture survives. French Louisiana, when it was sold by Napoleon in 1803, covered all or part of fifteen current U.S. states and contained French and Canadian colonists dispersed across it, though they were most numerous in its southernmost portion.

During the War of 1812, Louisiana residents of French origin took part on the American side in the Battle of New Orleans (December 23, 1814, through January 8, 1815). Jean Lafitte and his Baratarians later were honored by US General Andrew Jackson for their contribution to the defense of New Orleans.[12]

In Louisiana today, more than 15 percent of the population of the Cajun Country reported in the 2000 United States Census that French was spoken at home.[13]

Another significant source of immigrants to Louisiana was Saint-Domingue, which gained its independence as the Republic of Haiti in 1804, following Haitian Revolution; much of its white population (along with some mulattoes) fled during this time, often to New Orleans.[14]

Biloxi in Mississippi, and Mobile in Alabama, still contain French American heritage since they were founded by the Canadian Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville.

The Houma Tribe in Louisiana still speak the same French they had been taught 300 years ago.

Colonial era

In the 17th and early 18th centuries there was an influx of a few thousand Huguenots, who were Calvinist refugees fleeing religious persecution following the issuance of the 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau by Louis XIV of the Kingdom of France.[15] For nearly a century they fostered a distinctive French Protestant identity that enabled them to remain aloof from American society, but by the time of the American Revolution they had generally intermarried and merged into the larger Presbyterian community.[16] In 1700, they constituted 13 percent of the white population of the Province of Carolina and 5 percent of the white population of the Province of New York.[15] The largest number settling in South Carolina, where the French comprised four percent of the white population in 1790.[17][18] With the help of the well organized international Huguenot community, many also moved to Virginia.[19] In the north, Paul Revere of Boston was a prominent figure.

A new influx of French-heritage people occurred at the very end of the colonial era. Following the failed invasion of Quebec in 1775-1776, hundreds of French-Canadian men who had enlisted in the Continental Army remained in the ranks. Under colonels James Livingston and Moses Hazen, they saw military action across the main theaters of the Revolutionary War. At the end of the war, New York State formed the Canadian and Nova Scotia Refugee Tract stretching westward from Lake Champlain. Though many of the veterans sold their claim in this vast region, some remained and the settlement held. From early colonizing efforts in the 1780s to the era of Quebec's "great hemorrhage," the French-Canadian presence in Clinton County in northeastern New York was inescapable.[20]

Midwest

From the beginning of the 17th century, French Canadians explored and traveled to the region with their coureur de bois and explorers, such as Jean Nicolet, Robert de LaSalle, Jacques Marquette, Nicholas Perrot, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, Pierre Dugué de Boisbriant, Lucien Galtier, Pierre Laclède, René Auguste Chouteau, Julien Dubuque, Pierre de La Vérendrye and Pierre Parrant.

The French Canadians set up a number of villages along the waterways, including Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin; La Baye, Wisconsin; Cahokia, Illinois; Kaskaskia, Illinois; Detroit, Michigan; Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan; Saint Ignace, Michigan; Vincennes, Indiana; St. Paul, Minnesota; St. Louis, Missouri; and Sainte Genevieve, Missouri. They also built a series of forts in the area, such as Fort de Chartres, Fort Crevecoeur, Fort Saint Louis, Fort Ouiatenon, Fort Miami (Michigan), Fort Miami (Indiana), Fort Saint Joseph, Fort La Baye, Fort de Buade, Fort Saint Antoine, Fort Crevecoeur, Fort Trempealeau, Fort Beauharnois, Fort Orleans, Fort St. Charles, Fort Kaministiquia, Fort Michilimackinac, Fort Rouillé, Fort Niagara, Fort Le Boeuf, Fort Venango and Fort Duquesne. The forts were serviced by soldiers and fur trappers who had long networks reaching through the Great Lakes back to Montreal.[21] Sizable agricultural settlements were established in the Pays des Illinois.[22]

The region was relinquished by France to the British in 1763 as a result of the Treaty of Paris. Three years of war by the Natives, called Pontiac's War, ensued. It became part of the Province of Quebec in 1774, and was seized by the United States during the Revolution.[23]

New England, New York State

In the late 19th century, many Francophones arrived in New England from Quebec and New Brunswick to work in textile mill cities in New England. In the same period, Francophones from Quebec soon became a majority of the workers in the saw mill and logging camps in the Adirondack Mountains and their foothills. Others sought opportunities for farming and other trades such as blacksmiths in Northern New York State. By the mid-20th century Franco-Americans comprised 30 percent of Maine's population. Some migrants became lumberjacks but most concentrated in industrialized areas and into enclaves known as "Little Canadas".[24]

French Canadian women saw New England as a place of opportunity and possibility where they could create economic alternatives for themselves distinct from the expectations of their farm families in Canada. By the early 20th century some saw temporary migration to the United States to work as a rite of passage and a time of self-discovery and self-reliance. Most moved permanently to the United States, using the inexpensive railroad system to visit Quebec from time to time. When these women did marry, they had fewer children with longer intervals between children than their Canadian counterparts. Some women never married, and oral accounts suggest that self-reliance and economic independence were important reasons for choosing work over marriage and motherhood. These women conformed to traditional gender ideals in order to retain their 'Canadienne' cultural identity, but they also redefined these roles in ways that provided them increased independence in their roles as wives and mothers.[25][26] The Franco-Americans became active in the Catholic Church where they tried with little success to challenge its domination by Irish clerics.[27] They founded such newspapers as Le Messager and La Justice. The first hospital in Lewiston, Maine, became a reality in 1889 when the Sisters of Charity of Montreal, the 'Grey Nuns,' opened the doors of the Asylum of Our Lady of Lourdes. This hospital was central to the Grey Nuns' mission of providing social services for Lewiston's predominately French Canadian mill workers. The Grey Nuns struggled to establish their institution despite meager financial resources, language barriers, and opposition from the established medical community.[28] Immigration dwindled after World War I.

The French Canadian community in New England tried to preserve some of its cultural norms. This doctrine, like efforts to preserve francophone culture in Quebec, became known as la Survivance.[29] A product of the industrial economy of the regions at the time, by 1913, the French and French-Canadian populations of New York City, Fall River, Massachusetts and Manchester, New Hampshire were the largest in the country, and out of the top 20 largest Franco-American populations in the United States, only 4 were outside of New York and New England, with New Orleans ranking 18th largest in the nation.[30] Because of this, a number of French institutions were established in New England, including the Société Historique Franco-américaine in Boston, and the Union Saint-Jean-Baptiste d’Amérique of Woonsocket, the largest French-Catholic cultural and benefit society in the United States in the early 20th century.[31]

Potvin (2003) has studied the evolution of French Catholic parishes in New England. The predominantly Irish hierarchy of the 19th century was slow to recognize the need for French-language parishes; several bishops even called for assimilation and English language-only parochial schools. By the 20th century, a number of parochial schools for Francophone students opened, though they gradually closed toward the end of the century and a large share of the French-speaking population left the Church. At the same time, the number of priests available to staff these parishes also diminished.

By the 21st century the emphasis was on retaining local reminders of French American culture rather than on retaining the language itself.[32] With the decline of the state's textile industry during the 1950s, the French element experienced a period of upward mobility and assimilation. This pattern of assimilation increased during the 1970s and 1980s as many Catholic organizations switched to English names and parish children entered public schools; some parochial schools closed in the 1970s. Although some ties to its French Canadian origins remain, the community was largely anglicized by the 1990s, moving almost completely from 'Canadien' to 'American'.[24][33]

Noted American popular culture figures who maintained a close connection to their French roots include musician Rudy Vallée (1901–1986) who grew up in Westbrook, Maine, a child of a French-Canadian father and an Irish mother,[34] and counter-culture author Jack Kerouac (1922–1969) who grew up in Lowell, Massachusetts. Kerouac was the child of two French-Canadian immigrants, and wrote in both English and French. Franco-American politicians from New England include U.S. Senator Kelly Ayotte (R, New Hampshire) and Presidential adviser Jon Favreau, who was born and raised in Massachusetts.

Civil War

Franco-Americans in the Union forces were one of the most important Catholic groups present during the American Civil War. The exact number is unclear, but thousands of Franco-Americans appear to have served in this conflict. Union forces did not keep reliable statistics concerning foreign enlistments. However, historians have estimated anywhere from 20,000 to 40,000 Franco-Americans serving in this war. In addition to those born in the United States, many who served in the Union forces came from Canada or had resided there for several years. Canada's national anthem was written by such a soldier named Calixa Lavallée, who wrote this anthem while he served for the Union, attaining the rank of Lieutenant.[35] Leading Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard was a noted French American from Louisiana.

Politics

Walker (1962) examines the voting behavior in U.S. presidential elections from 1880 to 1960, using election returns from 30 Franco-American communities in New England, along with sample survey data for the 1948–60 elections. From 1896 to 1924, Franco-Americans typically supported the Republican Party because of its conservatism, emphasis on order, and advocacy of the tariff to protect the textile workers from foreign competition. In 1928, with Catholic Al Smith as the Democratic candidate, the Franco-Americans moved over to the Democratic column and stayed there for six presidential elections. They formed part of the New Deal Coalition. Unlike the Irish and German Catholics, very few Franco-Americans deserted the Democratic ranks because of the foreign policy and war issues of the 1940 and 1944 campaigns. In 1952 many Franco-Americans broke from the Democrats but returned heavily in 1960.[36]

As the ancestors of most Franco-Americans had for the most part left France before the French Revolution, they usually prefer the Fleur-de-lis to the modern French tricolor.[37]

Franco-American Day

In 2008, the state of Connecticut made June 24 Franco-American Day, recognizing French Canadians for their culture and influence on Connecticut. The states of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, have now also held Franco-American Day festivals on June 24.[38]

Demographics

According to the U.S. Census Bureau of 2000, 5.3 percent of Americans are of French or French Canadian ancestry. In 2013 the number of people living in the US who were born in France was estimated at 129,520.[39] Franco-Americans made up close to, or more than, 10 percent of the population of seven states, six in New England and Louisiana. Population wise, California has the greatest Franco population followed by Louisiana, while Maine has the highest by percentage (25 percent).

|

|

|

|

Historical immigration

Religion Most Franco Americans have a Roman Catholic heritage (which includes most French Canadians and Cajuns). Protestants would arrive in two smaller waves, with the earliest arrivals being the Huguenots who fled from France in the colonial era, many of whom would settle in Boston, Charleston, New York and Philadelphia.[44] Huguenots and their descendants would immigrate to the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the Provinces of Pennsylvania and Carolina due in large part to colonial anti-Catholic sentiment, during the period of the Edict of Fontainebleau.[45] The 19th century would see the arrival of others from Switzerland.[46] From the 1870s to the 1920s in particular, there was tension between the English-speaking Irish Catholics, who dominated the Church in New England, and the French immigrants, who wanted their language taught in the parochial schools. The Irish controlled all the Catholic colleges in New England, except for Assumption College in Massachusetts, controlled by the French and one school in New Hampshire controlled by Germans. Tensions between these two groups bubbled up in Fall River in 1884–1886, in Danielson, Connecticut and North Brookfield, Massachusetts in the 1890s and in Maine in the subsequent decades.[47][48][49][50] A breaking point was reached during the Sentinelle affair of the 1920s, in which Franco-American Catholics of Woonsocket,[51] Rhode Island, challenged their bishop over control of parish funds in an unsuccessful bid to wrest power from the Irish American episcopate.[52] In a 1957 treatise on urban history, American historian Constance Green would attribute some disputes between French and Irish Catholics in Massachusetts, Holyoke in particular, as fomented by Yankee English Protestants, in the hopes that a split would diminish Catholic influence.[53] Marie Rose Ferron was a mystic stigmatic; she was born in Quebec and lived in Woonsocket, Rhode Island. Between about 1925 and 1936, she was a popular "victim soul" who suffered physically to redeem the sins of her community. Father Onésime Boyer promoted her cult.[54] EducationCurrently there are multiple French international schools in the United States operated in conjunction with the Agency for French Education Abroad (AEFE).[55] French language in the United StatesAccording to the National Education Bureau, French is the second most commonly taught foreign language in American schools, behind Spanish. The percentage of people who learn French language in the United States is 12.3%.[39] French was the most commonly taught foreign language until the 1980s; when the influx of Hispanic immigrants aided the growth of Spanish. According to the U.S. 2000 Census, French is the third most spoken language in the United States after English and Spanish, with 2,097,206 speakers, up from 1,930,404 in 1990. The language is also commonly spoken by Haitian immigrants in Florida and New York City.[56] As a result of French immigration to what is now the United States in the 17th and 18th centuries, the French language was once widely spoken in a few dozen scattered villages in the Midwest. Migrants from Quebec after 1860 brought the language to New England. French-language newspapers existed in many American cities; especially New Orleans and in certain cities in New England. Americans of French descent often lived in predominantly French neighborhoods; where they attended schools and churches that used their language. Before 1920 French Canadian neighborhoods were sometimes known as "Little Canada".[57] After 1960, the "Little Canadas" faded away.[58] There were few French-language institutions other than Catholic churches. There were some French newspapers, but they had a total of only 50,000 subscribers in 1935.[59] The World War II generation avoided bilingual education for their children, and insisted they speak English.[60] By 1976, nine in ten Franco Americans usually spoke English and scholars generally agreed that "the younger generation of Franco-American youth had rejected their heritage."[61] SettlementsCities founded

States founded

HistoriographyRichard (2002) examines the major trends in the historiography regarding the Franco-Americans who came to New England in 1860–1930. He identifies three categories of scholars: survivalists, who emphasized the common destiny of Franco-Americans and celebrated their survival; regionalists and social historians, who aimed to uncover the diversity of the Franco-American past in distinctive communities across New England; and pragmatists, who argued that the forces of acculturation were too strong for the Franco-American community to overcome. The 'pragmatists versus survivalists' debate over the fate of the Franco-American community may be the ultimate weakness of Franco-American historiography. Such teleological stances have impeded the progress of research by funneling scholarly energies in limited directions while many other avenues, for example, Franco-American politics, arts, and ties to Quebec, remain insufficiently explored.[69] While a considerable number of pioneers of Franco-American history left the field or came to the end of their careers in the late 1990s, other scholars have moved the lines of debate in new directions in the last fifteen years. The "Franco" communities of New England have received less sustained scholarly attention in this period, but important work has no less appeared as historians have sought to assert the relevance of the French-Canadian diaspora to the larger narratives of American immigration, labor and religious history. Scholars have worked to expand the transnational perspective developed by Robert G. LeBlanc during the 1980s and 1990s.[70] Yukari Takai has studied the impact of recurrent cross-border migration on family formation and gender roles among Franco-Americans.[71] Florence Mae Waldron has expanded on older work by Tamara Hareven and Randolph Langenbach in her study of Franco-American women's work within prevalent American gender norms.[72] Waldron's innovative work on the national aspirations and agency of women religious in New England also merits mention.[73] Historians have pushed the lines of inquiry on Franco-Americans of New England in other directions as well. Recent studies have introduced a comparative perspective, considered the surprisingly understudied 1920s and 1930s, and reconsidered old debates on assimilation and religious conflict in light of new sources.[74][75][76] At the same time, there has been rapidly expanding research on the French presence in the middle and western part of the continent (the American Midwest, the Pacific coast, and the Great Lakes region) in the century following the collapse of New France.[77][78][79][80] Notable peopleSee alsoNotes

Citations

Further reading

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||