1892 United States presidential election

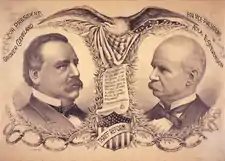

The 1892 United States presidential election was the 27th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 1892. In a rematch of the closely contested 1888 presidential election, former Democratic President Grover Cleveland defeated incumbent Republican President Benjamin Harrison. Cleveland's victory made him the first and to date only person in American history to be elected to a non-consecutive second presidential term. It was also the first time incumbents were defeated in consecutive elections—the second being Jimmy Carter's defeat of Gerald Ford in 1976, followed by Carter’s subsequent loss to Ronald Reagan in 1980.[2]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

444 members of the Electoral College 223 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 74.7%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

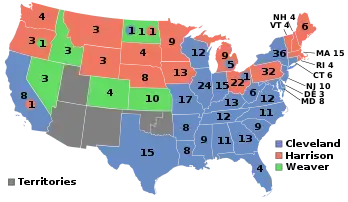

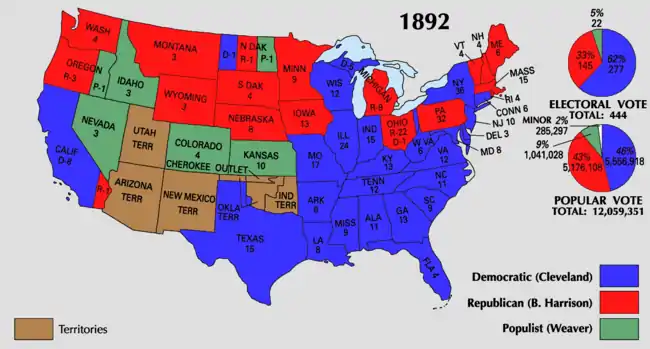

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Harrison/Reid, blue denotes those won by Cleveland/Stevenson, green denotes those won by Weaver/Field. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Though some Republicans opposed Harrison's re-nomination, Harrison defeated James G. Blaine and William McKinley on the first presidential ballot of the 1892 Republican National Convention. Cleveland defeated challenges by David B. Hill and Horace Boies on the first presidential ballot of the 1892 Democratic National Convention, becoming the first Democrat to win his party's presidential nomination in three elections. The new Populist Party, formed by groups from The Grange, the Farmers' Alliances, and the Knights of Labor, fielded a ticket led by former Congressman James B. Weaver of Iowa.

The campaign centered mainly on economic issues, especially the protectionist 1890 McKinley Tariff. Cleveland ran on a platform of lowering the tariff and opposed the Republicans' 1890 voting rights proposal. Cleveland was also a proponent of the gold standard, while the Republicans and Populists both supported bimetalism.

Cleveland swept the Solid South and won several important swing states, taking a majority of the electoral vote and a plurality of the popular vote. As of 2020, he is the third of six presidential nominees to win a significant number of electoral votes in at least three elections, the others being Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, William Jennings Bryan, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Richard Nixon. Of these, Jackson, Cleveland, and Roosevelt also won the popular vote in at least three elections. Weaver won 8.5% of the popular vote and carried several Western states, while John Bidwell of the Prohibition Party won 2.2% of the popular vote. The Democrats did not win another presidential election until 1912.

Nominations

Democratic Party nomination

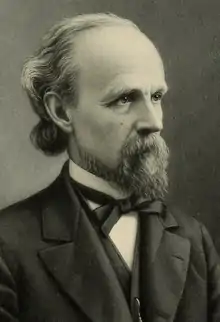

| Grover Cleveland | Adlai Stevenson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg.webp) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22nd President of the United States (1885–1889) |

Former U.S. Representative for Illinois's 13th (1875–1877 & 1879–1881) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By the beginning of 1892, many Americans were ready to return to Cleveland's political policies. Although he was the clear frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nomination, he was far from the universal choice of the party's supporters; many, such as the journalists Henry Watterson and Charles Anderson Dana, thought that if he were to attain the nomination, their party would lose in November, but few could challenge him effectively. Though he had remained relatively quiet on the issue of silver versus gold, often deferring to bimetalism, Senate Democrats in January 1891 voted for free coinage of silver. Furious, he sent a letter to Ellery Anderson, who headed the New York Reform Club, to condemn the party's apparent drift towards inflation and agrarian control, the "dangerous and reckless experiment of free, unlimited coinage of silver at our mints." Advisors warned that such statements might alienate potential supporters in the South and West and risk his chances for the nomination, but Cleveland felt that being right on the issue was more important than the nomination. After making his position clear, he worked to focus his campaign on tariff reform, hoping that the silver issue would dissipate.[3]

A challenger emerged in the form of David B. Hill, former governor of and incumbent senator from New York. In favor of bimetalism and tariff reform, Hill hoped to make inroads with Cleveland's supporters while appealing to those in the South and Midwest who were not keen on nominating Cleveland for a third consecutive time. Hill had begun to run for the position of president unofficially as early as 1890, and even offered former Postmaster General Donald M. Dickinson his support for the vice-presidential nomination. But he was not able to escape his past association with Tammany Hall, and lack of confidence in his ability to defeat Cleveland for the nomination kept Hill from attaining the support he needed. By the time of the convention, Cleveland could count on the support of majority of the state Democratic parties, though his native New York remained pledged to Hill.[4]

In a narrow first-ballot victory, Cleveland received 617.33 votes, barely 10 more than needed, to 114 for Hill, 103 for Governor Horace Boies of Iowa, a populist and former Republican, and the rest scattered. Although the Cleveland forces preferred Isaac P. Gray from Indiana for vice president, Cleveland directed his own support to the convention favorite, Adlai E. Stevenson I from Illinois.[5] As a supporter of using paper greenbacks and free silver to inflate the currency and alleviate economic distress in rural districts, Stevenson balanced the ticket headed by Cleveland, who supported hard-money and the gold standard. At the same time, it was hoped that his nomination represented a promise not to ignore regulars, and so potentially get Hill and Tammany Hall to support the Democratic ticket to their fullest in the coming election.[6][7]

Republican Party nomination

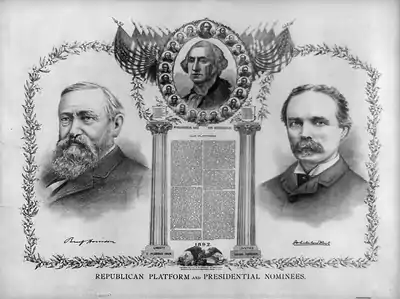

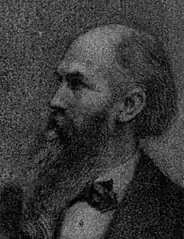

| Benjamin Harrison | Whitelaw Reid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23rd President of the United States (1889–1893) |

28th U.S. Ambassador to France (1889–1892) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Benjamin Harrison's administration was widely viewed as unsuccessful, and as a result, Thomas C. Platt (a political boss in New York) and other disaffected party leaders mounted a dump-Harrison movement coalescing around veteran candidate James G. Blaine from Maine, a favorite of Republican party regulars. Blaine had been the Republican nominee in 1884 when he was beaten by Democrat Grover Cleveland.

Privately, Harrison did not want to be renominated for the presidency, but he remained opposed to the nomination going to Blaine, who he was convinced intended to run, and thought himself the only candidate capable of preventing that. Blaine, however, did not want another fight for the nomination and a rematch against Cleveland at the general election. His health had begun to fail, and three of his children had recently died (Walker and Alice in 1890, and Emmons in 1892). Blaine refused to run actively, but the cryptic nature of his responses to a draft effort fueled speculation that he was not averse to such a movement. For his part, Harrison curtly demanded that he either renounce his supporters or resign his position as Secretary of State, with Blaine choosing the latter a scant three days before the National Convention. A boom began to build around the "draft Blaine" effort with supporters hoping to cause a break towards their candidate.[8]

Senator John Sherman from Ohio, who had been the leading candidate for the nomination at the 1888 Republican Convention before Harrison won it, was also brought up as a possible challenger. Like Blaine, however, he was averse to another bitter battle for the nomination and "like the rebels down South, want to be let alone." This inevitably turned attention to Ohio Governor William McKinley, who was indecisive as to his intentions in spite of his ill feelings toward Harrison and popularity among the Republican base. Not averse to receiving the nomination, he did not expect to win it either. However, should Blaine and Harrison fail to attain the nomination after a number of ballots, he felt he could be brought forth as a harmony candidate. Despite the urging of Republican power broker Mark Hanna, McKinley did not put himself forward as a potential candidate, afraid of offending Harrison and Blaine's supporters, while also feeling that the coming election would not favor the Republicans.[9]

In any case, the president's forces had the nomination locked up by the time delegates met in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on June 7–10, 1892. Richard Thomas from Indiana delivered Harrison's nominating speech. Harrison was nominated on the first ballot with 535.17 votes to 182.83 for Blaine, 182 for McKinley, and the rest scattered. McKinley protested when the Ohio delegation threw its entire vote in his name, despite not being formally nominated, but Joseph B. Foraker, who headed the delegation, managed to silence him on a point of order.[10] With the ballots counted, many observers were surprised at the strength of the McKinley vote, which almost overtook Blaine. Whitelaw Reid from New York, editor of the New York Tribune and recent United States Ambassador to France, was nominated for vice president. The incumbent vice president, Levi P. Morton, was supported by many at the convention, including Reid himself, but did not wish to serve another term.[10] Harrison also did not want Morton on the ticket.

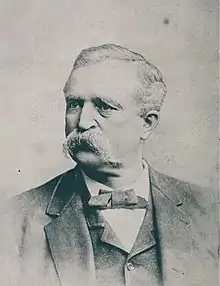

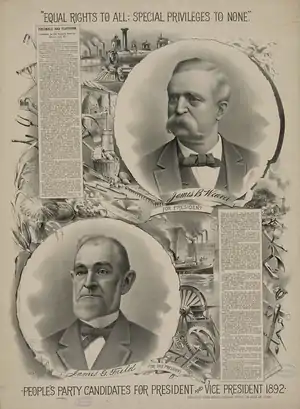

People's Party nomination

| 1892 People's Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| James B. Weaver | James G. Field | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Former U.S. Representative for Iowa's 6th (1879–1881 & 1885–1889) |

13th Attorney General of Virginia (1877–1882) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Populist candidates:

- James B. Weaver, former U.S. representative from Iowa

- James H. Kyle, U.S. senator from South Dakota

- Leonidas L. Polk, former representative from North Carolina

- Walter Q. Gresham, Appellate judge from Indiana

Candidates gallery

James B. Weaver

from Iowa

Leonidas L. Polk

from North Carolina

(Died June 11, 1892)

Appellate Judge

Walter Q. Gresham

from Indiana

(Declined to be Nominated)

In 1891, the American farmers' alliances met with delegates from labor and reform groups in Cincinnati, Ohio, to discuss the formation of a new political party. They formed the People's Party, commonly known as the "Populists", a year later in St. Louis, Missouri.

Leonidas L. Polk was the initial frontrunner to the presidential nomination. He had been instrumental in the party's formation and held great appeal with its agrarian base, but he unexpectedly died while in Washington, D.C., on June 11. Another candidate mentioned frequently for the nomination was Walter Q. Gresham, an appellate judge who had made a number of rulings against the railroads that made him a favorite of some farmer and labor groups, and it was felt that his rather dignified image would make the Populists appear as more than a minor contender. Both Democrats and Republicans feared his nomination for this reason, and while Gresham toyed with the idea, he ultimately was not ready to make a complete break with the two parties, declining petitions for his nomination right up to and during the Populist Convention. Later he would endorse Grover Cleveland for the presidency.[11]

At the first Populist national convention in Omaha, Nebraska, in July 1892, James B. Weaver from Iowa was nominated for president on the first ballot, now lacking any serious opposition. While his nomination brought with him significant campaigning experience from over several decades, he also had a longer tract of history for which Republicans and Democrats could criticize him, and he also alienated many potential supporters in the South, having participated in Sherman's March to the Sea. James G. Field from Virginia was nominated for vice-president to try and rectify this problem while also attaining the regional balance often seen in Republican and Democratic tickets.[12] I

| Presidential Ballot | Vice Presidential Ballot | ||

| Ballot | 1st | 1st | |

|---|---|---|---|

| James B. Weaver | 995 | James G. Field | 733 |

| James H. Kyle | 265 | Ben Stockton Terrell | 554 |

| Seymour F. Norton | 1 | ||

| Mann Page | 1 | ||

| Others | 1 | ||

Source: US President – P Convention. Our Campaigns. (September 7, 2009). Source: US Vice President – P Convention. Our Campaigns. (September 7, 2009).

The Populist platform called for nationalization of the telegraph, telephone, and railroads, free coinage of silver, a graduated income tax, and creation of postal savings banks.

Prohibition Party nomination

Prohibition candidates:

- John Bidwell, former U.S. representative from California

- Gideon T. Stewart, Prohibition Party Chairman from Ohio

- William Jennings Demorest, magazine publisher from New York

Candidates gallery

Prohibition Party Chairman

Gideon T. Stewart

from Ohio

Magazine Publisher

William J. Demorest

from New York

The sixth Prohibition Party National Convention assembled in Music Hall in Cincinnati, Ohio. There were 972 delegates present from all states except Louisiana and South Carolina.

Two major stories about the convention loomed before it assembled. In the first place, some members of the national committee sought to merge the Prohibition and Populist Parties. While there appeared a likelihood that the merger would materialize, it was clear that it was not going to happen by the time that the convention convened. Secondly, the southern states sent a number of black delegates. Cincinnati hotels refused to serve meals to blacks and whites at the same time, and several hotels refused service to the black delegates altogether.

The convention nominated John Bidwell from California for president on the first ballot. Prior to the convention, the race was thought to be close between Bidwell and William Jennings Demorest, but the New York delegation became irritated with Demorest and voted for Bidwell 73–7. James B. Cranfill from Texas was nominated for vice-president on the first ballot with 417 votes to 351 for Joshua Levering from Maryland and 45 for others.[13]

| Presidential Ballot | |

| Ballot | 1st |

|---|---|

| John Bidwell | 590 |

| Gideon T. Stewart | 179 |

| William Jennings Demorest | 139 |

| H. Clay Bascom | 3 |

Source: US President – P Convention. Our Campaigns. (May 9, 2010).

Socialist Labor Party Nomination

The first Socialist Labor Party National Convention assembled in New York City and, despite running on a platform that called for the abolition of the positions of president and vice-president, decided to nominate candidates for those positions: Simon Wing from Massachusetts for president and Charles Matchett from New York for vice-president. They were on the ballot in five states: Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania.[14]

General election

Campaign

The tariff issue dominated this rather lackluster campaign. Harrison defended the protectionist McKinley Tariff passed during his term. For his part, Cleveland assured voters that he opposed absolute free trade and would continue his campaign for a reduction in the tariff. Cleveland also denounced the Lodge Bill, a voting rights bill that sought to protect the rights of African American voters in the South.[15] William McKinley campaigned extensively for Harrison, setting the stage for his own run four years later.

The campaign took a somber turn when, in October, First Lady Caroline Harrison died. Despite the ill health that had plagued Mrs. Harrison since her youth and had worsened in the last decade, she often accompanied Mr. Harrison on official travels. On one such trip, to California in the spring of 1891, she caught a cold. It quickly deepened into her chest, and she was eventually diagnosed with tuberculosis. A summer in the Adirondack Mountains failed to restore her to health. An invalid the last six months of her life, she died in the White House on October 25, 1892, just two weeks before the national election. As a result, all of the candidates ceased campaigning.

Results

The margin in the popular vote for Cleveland was 400,000, the largest since Grant's re-election in 1872.[16] The Democrats won the presidency and both houses of Congress for the first time since 1856. President Harrison's re-election bid was a decisive loss in both the popular and electoral count, unlike President Cleveland's re-election bid four years earlier, in which he won the popular vote, but lost the electoral vote. Cleveland was the third of only five presidents to win re-election with a smaller percentage of the popular vote than in previous elections, although in the two prior such incidents — James Madison in 1812 and Andrew Jackson in 1832 — not all states held popular elections. Ironically, Cleveland saw his popular support decrease not only from his electoral win in 1884, but also from his electoral loss in 1888. A similar vote decrease would happen again for Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940 and 1944 and Barack Obama in 2012.

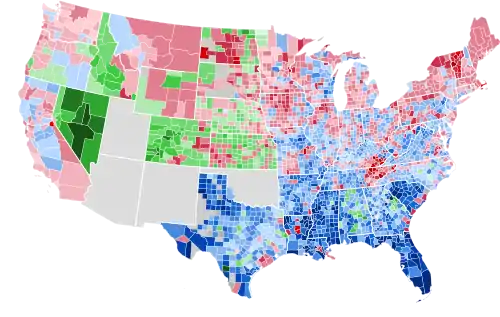

At the county level, the Democratic candidate fared much better than the Republican candidate. The Republicans' vote was not nearly as widespread as the Democrats. In 1892, it was still a sectionally based party mainly situated in the East, Midwest, and West and was barely visible south of the Mason–Dixon line. In the South, the party was holding on in only a few counties. In East Tennessee and tidewater Virginia, the vote at the county level showed some strength, but it barely existed in Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas.[17]

In a continuation of its collapse there during the 1890 Congressional elections, the Republican Party even struggled in its Midwestern strongholds, where general electoral troubles from economic woes were acutely exacerbated by the promotion of temperance laws and, in Wisconsin and Illinois, the aggressive support of state politicians for English-only compulsory education laws. Such policies, which particularly in the case of the latter were associated with an upwelling of nativist and anti-Catholic attitudes amongst their supporters, resulted in the defection of large sections of immigrant communities, especially Germans, to the Democratic Party. Cleveland carried Wisconsin and Illinois with their 36 combined electoral votes, a Democratic victory not seen in those states since 1852[18] and 1856[19] respectively, and which would not be repeated until Woodrow Wilson's election in 1912. While not as dramatic a loss as in 1890, it would take until the next election cycle for more moderate Republican leaders to pick up the pieces left by the reformist crusaders and bring alienated immigrants back to the fold.[20]

Of the 2,683 counties making returns, Cleveland won in 1,389 (51.77%), Harrison carried 1,017 (37.91%), while Weaver placed first in 276 (10.29%). One county (0.04%) split evenly between Cleveland and Harrison.

Populist James B. Weaver, calling for free coinage of silver and an inflationary monetary policy, received such strong support in the West that he become the only third-party nominee between 1860 and 1912 to carry a single state. The Democratic Party did not have a presidential ticket on the ballot in the states of Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, North Dakota, or Wyoming, and Weaver won the first four of these states.[21] Weaver also performed well in the South as he won counties in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Texas. Populists did best in Alabama, where electoral chicanery probably carried the day for the Democrats.[16]

The Prohibition ticket received 270,879, or 2.2% nationwide. It was the largest total vote and highest percentage of the vote received by any Prohibition Party national ticket.

Wyoming, having attained statehood two years earlier, became the first state to allow women to vote in a presidential election since 1804. (Women in New Jersey had the right to vote under the state's original constitution, but this right was rescinded in 1807.)

Wyoming was also one of six states (along with North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, and Idaho) participating in their first presidential election. This was the most new states voting since the first election.

The election witnessed many states splitting their electoral votes. Electors from the state of Michigan were selected using the congressional district method (the winner in each congressional district wins one electoral vote, the winner of the state wins two electoral votes). This resulted in a split between the Republican and Democratic electors: nine for Harrison and five for Cleveland.[22] In Oregon, the direct election of presidential electors combined with the fact that one Weaver elector was endorsed by the Democratic Party and elected as a Fusionist, resulted in a split between the Republican and Populist electors: three for Harrison and one for Weaver.[22] In California, the direct election of presidential electors combined with the close race resulted in a split between the Republican and Democratic electors: eight for Cleveland and one for Harrison.[22] In Ohio, the direct election of presidential electors combined with the close race resulted in a split between the Republican and Democratic electors: 22 for Harrison and one for Cleveland.[22] In North Dakota, two electors from the Democratic-Populist Fusion ticket won and one Republican Elector won. This created a split delegation of electors: one for Weaver, one for Harrison, and one for Cleveland.[22]

This was the first occasion in which incumbent presidents were defeated in two consecutive elections. This would not happen again until 1980. Harrison's loss also marked the only time until Donald Trump's defeat in 2020 that the Republican Party lost the White House after only one term, and lost the popular vote twice in a row.

This was the last election in which the Democrats won California until 1916 (although it voted against the Republicans by supporting the Progressive Party in 1912), the last in which the Democrats won Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, New Jersey, New York, West Virginia[23] and Wisconsin[18] until 1912, the last in which the Democrats won a majority of electoral votes in Maryland until 1904, and the last in which the Republicans won Montana until 1904. The election was also the last in which the Democrats didn't win Colorado and Nevada until 1904.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Stephen Grover Cleveland | Democratic | New York | 5,553,898 | 46.02% | 277 | Adlai Ewing Stevenson | Illinois | 277 |

| Benjamin Harrison (Incumbent) | Republican | Indiana | 5,190,819 | 43.01% | 145 | Whitelaw Reid | New York | 145 |

| James Baird Weaver | Populist | Iowa | 1,026,595 | 8.51% | 22 | James Gaven Field | Virginia | 22 |

| John Bidwell | Prohibition | California | 270,879 | 2.24% | 0 | James Britton Cranfill | Texas | 0 |

| Simon Wing | Socialist Labor | Massachusetts | 21,173 | 0.18% | 0 | Charles Horatio Matchett | New York | 0 |

| Other | 4,673 | 0.04% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 12,068,037 | 100% | 444 | 444 | ||||

| Needed to win | 223 | 223 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1892 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005.

Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Geography of results

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

Map of presidential election results by county

Map of presidential election results by county Map of Democratic presidential election results by county

Map of Democratic presidential election results by county Map of Republican presidential election results by county

Map of Republican presidential election results by county Map of Populist presidential election results by county

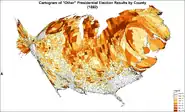

Map of Populist presidential election results by county Map of "Other" presidential election results by county

Map of "Other" presidential election results by county Cartogram of presidential election results by county

Cartogram of presidential election results by county Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county Cartogram of Populist presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Populist presidential election results by county Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Cartogram of "other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

Source: Data from Walter Dean Burnham, Presidential ballots, 1836–1892 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1955) pp 247–57.[24]

| States/districts won by Cleveland/Stevenson |

| States/districts won by Harrison/Reid |

| States/districts won by Weaver/Field |

| Grover Cleveland Democratic |

Benjamin Harrison Republican |

James Weaver Populist |

John Bidwell Prohibition |

Simon Wing Socialist Labor |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | state/dist. |

| Alabama | 11 | 138,135 | 59.40 | 11 | 9,184 | 3.95 | - | 84,984 | 36.55 | - | 240 | 0.10 | - | - | - | - | 53,151 | 22.86 | 232,543 | AL |

| Arkansas | 8 | 87,834 | 59.30 | 8 | 47,072 | 31.78 | - | 11,831 | 7.99 | - | 113 | 0.08 | - | - | - | - | 40,762 | 27.52 | 148,117 | AR |

| California | 9 | 118,174 | 43.83 | 8 | 118,027 | 43.78 | 1 | 25,311 | 9.39 | - | 8,096 | 3.00 | - | - | - | - | 147 | 0.05 | 269,609 | CA |

| Colorado | 4 | - | - | - | 38,620 | 41.13 | - | 53,584 | 57.07 | 4 | 1,687 | 1.80 | - | - | - | - | -14,964 | -15.94 | 93,891 | CO |

| Connecticut | 6 | 82,395 | 50.06 | 6 | 77,032 | 46.80 | - | 809 | 0.49 | - | 4,026 | 2.45 | - | 333 | 0.20 | - | 5,363 | 3.26 | 164,595 | CT |

| Delaware | 3 | 18,581 | 49.90 | 3 | 18,077 | 48.55 | - | - | - | - | 564 | 1.51 | - | - | - | - | 504 | 1.35 | 37,235 | DE |

| Florida | 4 | 30,153 | 85.01 | 4 | - | - | - | 4,843 | 13.65 | - | 475 | 1.34 | - | - | - | - | 25,310 | 71.35 | 35,471 | FL |

| Georgia | 13 | 129,446 | 58.01 | 13 | 48,408 | 21.70 | - | 41,939 | 18.80 | - | 988 | 0.44 | - | - | - | - | 81,038 | 36.32 | 223,126 | GA |

| Idaho | 3 | - | - | - | 8,599 | 44.31 | - | 10,520 | 54.21 | 3 | 288 | 1.48 | - | - | - | - | -1,921 | -9.90 | 19,407 | ID |

| Illinois | 24 | 426,281 | 48.79 | 24 | 399,288 | 45.70 | - | 22,207 | 2.54 | - | 25,871 | 2.96 | - | - | - | - | 26,993 | 3.09 | 873,647 | IL |

| Indiana | 15 | 262,740 | 47.46 | 15 | 255,615 | 46.17 | - | 22,208 | 4.01 | - | 13,050 | 2.36 | - | - | - | - | 7,125 | 1.29 | 553,613 | IN |

| Iowa | 13 | 196,367 | 44.31 | - | 219,795 | 49.60 | 13 | 20,595 | 4.65 | - | 6,402 | 1.44 | - | - | - | - | -23,428 | -5.29 | 443,159 | IA |

| Kansas | 10 | - | - | - | 157,241 | 48.40 | - | 163,111 | 50.20 | 10 | 4,553 | 1.40 | - | - | - | - | -5,870 | -1.81 | 324,905 | KS |

| Kentucky | 13 | 175,461 | 51.48 | 13 | 135,462 | 39.74 | - | 23,500 | 6.89 | - | 6,441 | 1.89 | - | - | - | - | 39,999 | 11.73 | 340,864 | KY |

| Louisiana | 8 | 87,926 | 76.53 | 8 | 26,963 | 23.47 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 60,963 | 53.06 | 114,889 | LA |

| Maine | 6 | 48,049 | 41.26 | - | 62,936 | 54.05 | 6 | 2,396 | 2.06 | - | 3,066 | 2.63 | - | - | - | - | -14,887 | -12.78 | 116,451 | ME |

| Maryland | 8 | 113,866 | 53.39 | 8 | 92,736 | 43.48 | - | 796 | 0.37 | - | 5,877 | 2.76 | - | - | - | - | 21,130 | 9.91 | 213,275 | MD |

| Massachusetts | 15 | 176,813 | 45.22 | - | 202,814 | 51.87 | 15 | 3,210 | 0.82 | - | 7,539 | 1.93 | - | 649 | 0.17 | - | -26,001 | -6.65 | 391,028 | MA |

| Michigan | 2 | 201,624 | 43.26 | - | 222,708 | 47.79 | 2 | 19,931 | 4.28 | - | 20,857 | 4.48 | - | - | - | - | -21,084 | -4.52 | 466,045 | MI |

| MI-1 | 1 | 19,990 | 51.33 | 1 | 18,323 | 47.05 | - | 291 | 0.75 | - | 340 | 0.87 | - | - | - | - | 1,667 | 4.28 | 38,944 | MI-1 |

| MI-2 | 1 | 22,427 | 47.67 | 1 | 20,947 | 44.89 | - | 1,072 | 2.30 | - | 2,401 | 5.15 | - | - | - | - | 1,480 | 3.17 | 46,667 | MI-2 |

| MI-3 | 1 | 15,750 | 37.01 | - | 21,233 | 49.98 | 1 | 2,938 | 6.92 | - | 2,562 | 6.03 | - | - | - | - | -5,477 | -12.89 | 42,483 | MI-3 |

| MI-4 | 1 | 20,084 | 46.16 | - | 21,402 | 49.19 | 1 | - | - | - | 2,024 | 4.65 | - | - | - | - | -1,381 | -3.17 | 43,510 | MI-4 |

| MI-5 | 1 | 20,187 | 47.72 | 1 | 18,173 | 42.96 | - | 1,980 | 4.68 | - | 1,967 | 4.65 | - | - | - | - | 2,014 | 4.76 | 42,307 | MI-5 |

| MI-6 | 1 | 19,500 | 43.16 | - | 21,324 | 47.19 | 1 | 2,070 | 4.58 | - | 2,286 | 5.06 | - | - | - | - | -1,734 | -3.84 | 45,180 | MI-6 |

| MI-7 | 1 | 15,984 | 46.57 | 1 | 15,723 | 45.80 | - | 1,842 | 5.37 | - | 777 | 2.26 | - | - | - | - | 201 | 0.59 | 34,326 | MI-7 |

| MI-8 | 1 | 15,298 | 44.55 | - | 16,672 | 48.55 | 1 | 1,149 | 3.35 | - | 1,218 | 3.35 | - | - | - | - | -1,374 | -4.00 | 34,337 | MI-8 |

| MI-9 | 1 | 12,853 | 43.36 | - | 14,036 | 47.35 | 1 | 1,062 | 3.58 | - | 1,693 | 5.71 | - | - | - | - | -1,183 | -3.99 | 29,664 | MI-9 |

| MI-10 | 1 | 14,972 | 47.91 | 1 | 14,370 | 45.98 | - | 1,167 | 3.73 | - | 741 | 2.37 | - | - | - | - | 602 | 1.93 | 31,250 | MI-10 |

| MI-11 | 1 | 12,743 | 35.16 | - | 18,379 | 50.75 | 1 | 3,143 | 8.68 | - | 1,961 | 5.41 | - | - | - | - | -5,645 | -15.59 | 36,217 | MI-11 |

| MI-12 | 1 | 16,888 | 42.68 | - | 18,811 | 50.06 | 1 | 1,023 | 2.59 | - | 1,851 | 4.68 | - | - | - | - | -2,923 | -7.39 | 39,573 | MI-12 |

| Minnesota | 9 | 100,920 | 37.76 | - | 122,823 | 45.96 | 9 | 29,313 | 10.97 | - | 14,182 | 5.31 | - | - | - | - | -21,903 | -8.20 | 267,238 | MN |

| Mississippi | 9 | 40,030 | 76.22 | 9 | 1,398 | 2.66 | - | 10,118 | 19.27 | - | 973 | 1.85 | - | - | - | - | 29,912 | 56.95 | 52,519 | MS |

| Missouri | 17 | 268,400 | 49.56 | 17 | 227,646 | 42.03 | - | 41,204 | 7.61 | - | 4,333 | 0.80 | - | - | - | - | 40,754 | 7.52 | 541,583 | MO |

| Montana | 3 | 17,690 | 39.79 | - | 18,871 | 42.44 | 3 | 7,338 | 16.50 | - | 562 | 1.26 | - | - | - | - | -1,181 | -2.66 | 44,461 | MT |

| Nebraska | 8 | 24,943 | 12.46 | - | 87,213 | 43.56 | 8 | 83,134 | 41.53 | - | 4,902 | 2.45 | - | - | - | - | -4,079 | -2.04 | 200,192 | NE |

| Nevada | 3 | 714 | 6.56 | - | 2,811 | 25.84 | - | 7,264 | 66.78 | 3 | 89 | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | -4,453 | -40.94 | 10,878 | NV |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 42,081 | 47.11 | - | 45,658 | 51.11 | 4 | 293 | 0.33 | - | 1,297 | 1.45 | - | - | - | - | -3,577 | -4.00 | 89,329 | NH |

| New Jersey | 10 | 171,066 | 50.67 | 10 | 156,101 | 46.24 | - | 985 | 0.29 | - | 8,134 | 2.41 | - | 1,337 | 0.40 | - | 14,965 | 4.43 | 337,623 | NJ |

| New York | 36 | 654,868 | 48.99 | 36 | 609,350 | 45.58 | - | 16,429 | 1.23 | - | 38,190 | 2.86 | - | 17,956 | 1.34 | - | 45,518 | 3.41 | 1,336,793 | NY |

| North Carolina | 11 | 132,951 | 47.44 | 11 | 100,346 | 35.80 | - | 44,336 | 15.82 | - | 2,637 | 0.94 | - | - | - | - | 32,605 | 11.63 | 280,270 | NC |

| North Dakota | 3 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 17,519 | 48.50 | 1 | 17,700 | 49.01 | 1 | 899 | 2.49 | - | - | - | - | -181 | -0.50 | 36,118 | ND |

| Ohio | 23 | 404,115 | 47.53 | 1 | 405,187 | 47.66 | 22 | 14,850 | 1.75 | - | 26,012 | 3.06 | - | - | - | - | -1,072 | -0.13 | 850,164 | OH |

| Oregon | 4 | 14,243 | 18.15 | - | 35,002 | 44.59 | 3 | 26,965 | 34.35 | 1 | 2,281 | 2.91 | - | - | - | - | -8,037 | -10.24 | 78,491 | OR |

| Pennsylvania | 32 | 452,264 | 45.09 | - | 516,011 | 51.45 | 32 | 8,714 | 0.87 | - | 25,123 | 2.50 | - | 898 | 0.09 | - | -63,747 | -6.36 | 1,003,010 | PA |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 24,336 | 45.75 | - | 26,975 | 50.71 | 4 | 228 | 0.43 | - | 1,654 | 3.11 | - | - | - | - | -2,639 | -4.96 | 53,196 | RI |

| South Carolina | 9 | 54,680 | 77.56 | 9 | 13,345 | 18.93 | - | 2,407 | 3.41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 41,335 | 58.63 | 70,504 | SC |

| South Dakota | 4 | 9,081 | 12.88 | - | 34,888 | 49.48 | 4 | 26,544 | 37.64 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -8,344 | -11.83 | 70,513 | SD |

| Tennessee | 12 | 136,468 | 51.36 | 12 | 100,537 | 37.83 | - | 23,918 | 9.00 | - | 4,809 | 1.81 | - | - | - | - | 35,931 | 13.52 | 265,732 | TN |

| Texas | 15 | 239,148 | 56.65 | 15 | 81,144 | 19.22 | - | 99,688 | 23.61 | - | 2,165 | 0.51 | - | - | - | - | 139,460 | 33.04 | 422,145 | TX |

| Vermont | 4 | 16,325 | 29.26 | - | 37,992 | 68.09 | 4 | 44 | 0.08 | - | 1,424 | 2.55 | - | - | - | - | -21,667 | -38.83 | 55,796 | VT |

| Virginia | 12 | 164,136 | 56.17 | 12 | 113,098 | 38.70 | - | 12,275 | 4.20 | - | 2,729 | 0.93 | - | - | - | - | 51,038 | 17.46 | 292,238 | VA |

| Washington | 4 | 29,802 | 33.88 | - | 36,460 | 41.45 | 4 | 19,165 | 21.79 | - | 2,542 | 2.89 | - | - | - | - | -6,658 | -7.57 | 87,969 | WA |

| West Virginia | 6 | 84,467 | 49.37 | 6 | 80,292 | 46.93 | - | 4,167 | 2.44 | - | 2,153 | 1.26 | - | - | - | - | 4,175 | 2.44 | 171,079 | WV |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 177,325 | 47.72 | 12 | 171,101 | 46.05 | - | 10,019 | 2.70 | - | 13,136 | 3.54 | - | - | - | - | 6,224 | 1.68 | 371,581 | WI |

| Wyoming | 3 | - | - | - | 8,454 | 50.52 | 3 | 7,722 | 46.14 | - | 530 | 3.17 | - | - | - | - | -732 | -4.37 | 16,735 | WY |

| TOTALS: | 444 | 5,553,898 | 46.02 | 277 | 5,190,799 | 43.01 | 145 | 1,026,595 | 8.51 | 22 | 270,889 | 2.24 | - | 21,173 | 0.18 | - | 363,099 | 3.01 | 12,068,027 | US |

Close states

Margin of victory less than 1% (35 electoral votes):

- California, 0.05%

- Ohio, 0.13%

- North Dakota, 0.50%

Margin of victory between 1% and 5% (158 electoral votes):

- Indiana, 1.29%

- Delaware, 1.35%

- Wisconsin, 1.68%

- Kansas, 1.81%

- Nebraska, 2.04%

- West Virginia, 2.44%

- Montana, 2.66%

- Illinois, 3.09% (tipping point state)

- Connecticut, 3.26%

- New York, 3.41%

- New Hampshire, 4.00%

- Wyoming, 4.37%

- New Jersey, 4.43%

- Michigan, 4.52%

- Rhode Island, 4.96%

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (101 electoral votes):

- Iowa, 5.29%

- Pennsylvania, 6.36%

- Massachusetts, 6.65%

- Missouri, 7.52%

- Washington, 7.57%

- Minnesota, 8.20%

- Idaho, 9.90%

- Maryland, 9.91%

Tipping point states:

See also

- 1892 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1892 and 1893 United States Senate elections

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

- Second inauguration of Grover Cleveland

References

- "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- "Historical U.S. Presidential Elections 1789-2016". Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- History of American Presidential Elections, Volume II, Pg 1710–1711

- History of American Presidential Elections, Volume II, Pg 1711–1714

- William DeGregorio, The Complete Book of U.S. Presidents, Gramercy 1997

- "VP Adlai Stevenson". Senate.gov. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- History of American Presidential Elections, Volume II, p. 1719–1720

- History of American Presidential Elections, Volume II, Pgs 1706–1708

- History of American Presidential Elections, Volume II, Pgs 1706–1707

- History of American Presidential Elections, Volume II, Pgs 1716

- History of American Presidential Elections Volume II 1848–1896; Schlesinger; Pgs 1721–1722

- History of American Presidential Elections Volume II 1848–1896; Schlesinger; Pgs 1722–1723

- "US President – PRB Convention Race – Jun 29, 1892". Our Campaigns. February 24, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- "US President – SLP Convention Race – Aug 28, 1892". Our Campaigns. January 28, 2006. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- Sig Synnestvedt, The White Response to Black Emancipation: Second-class Citizenship in the United States Since Reconstruction. (1972). p 41.

- Charles W. Calhoun (ed.), The Gilded Age: Perspectives on the Origins of Modern America. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2006; pg. 295.

- Presidential Elections, 1789–2008: County, State, and National Mapping of Election Data, Donald R. Deskins, Jr., Hanes Walton, Jr., and Sherman C. Puckett, pg. 250

- Counting the Votes; Wisconsin

- Counting the Votes; Illinois

- Jensen, Richard J. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896, ch. 4: Iowa, Wet or Dry? & ch. 5: Education, the Tariff, and the Melting Pot. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1971. pp. 89-153.

- Nathan Fine, Farmer and Labor Parties in the United States, 1828–1928. New York: Rand School of Social Science, 1928; pg. 79.

- Counting the Votes; West Virginia

- "1892 Presidential General Election Data – National". Uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

Further reading

- Ander, O. Fritiof. "The Swedish-American Press and the Election of 1892." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 23.4 (1937): 533–554. online

- Blaine, James G. "The Presidential Election of 1892." The North American Review 155#432 (1892): 513–525. online, a primary source

- Faulkner, Harold U. (1959). Politics, Reform and Expansion, 1890–1900. New York: Harper.

- Jensen, Richard (1971). The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-39825-0.

- Josephson, Matthew (1938). The Politicos: 1865–1896. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co.

- Keller, Morton (1977). Affairs of State: Public Life in Late Nineteenth Century America. Cambridge: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-00721-2.

- Kleppner, Paul (1979). The Third Electoral System 1853–1892: Parties, Voters, and Political Cultures. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1328-1.

- Knoles, George H. (1942). The Presidential Campaign and Election of 1892. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Knoles, George Harmon. "Populism and Socialism, with Special Reference to the Election of 1892." Pacific Historical Review 12.3 (1943): 295–304. online

- Morgan, H. Wayne (1969). From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877–1896. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

- Nevins, Allan. Grover Cleveland: A Study in Courage (1932) Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, the major resource on Cleveland.

- Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. A History of the United States since the Civil War. Volume V, 1888–1901 (1937). pp 169–244.

- Sievers, Harry J. "The Catholic Indian school issue and the presidential election of 1892." Catholic Historical Review 38.2 (1952): 129–155. online

- Steelman, Joseph F. "Vicissitudes of Republican Party Politics: The Campaign of 1892 in North Carolina." North Carolina Historical Review 43.4 (1966): 430–442. online

- Rhodes, James Ford (1920). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the Mckinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. 8. New York: Macmillan.

Primary sources

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1892. |

- United States presidential election of 1892 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Presidential Election of 1892: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- 1892 popular vote by counties

- 1892 State-by-state Popular vote

- Overview of 1892 Democratic National Convention

- How close was the 1892 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Election of 1892 in Counting the Votes