1981 Mississippi's 4th congressional district special election

A special election to determine the member of the United States House of Representatives for Mississippi's 4th congressional district was held on June 23, 1981, with a runoff held two weeks later on July 6. Democrat Wayne Dowdy defeated Republican Liles Williams in the runoff by 912 votes. Dowdy replaced Republican U.S. Representative Jon Hinson, who resigned from Congress following his arrest for engaging in sodomy.

| |||||||||||||||||

Mississippi's 4th congressional district | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Mississippi |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

Mississippi's state law requires the Governor of Mississippi to call for a special election to be held to fill any vacancies. The election date is held 40 to 60 days after the Governor has officially sent out notice.[1] All candidates run on one ballot, with a runoff election scheduled for the first- and second-place finishers if no candidate received 50% of the vote.

After Hinson's resignation, Republican Liles Williams won a primary nominating convention and faced multiple Democrats in the first round of the campaign. Williams finished in first place but failed to reach the majority vote required to avoid a runoff. He was seen as the favorite to with the election against the Democratic Mayor of McComb, Wayne Dowdy, who reached the runoff election with him. Williams ran his campaign sticking closely to President Ronald Reagan's policies – the 4th district had backed Reagan in the 1980 presidential election. Dowdy opposed the Reagan administration's tax cuts, specifically citing its cuts to Social Security and education. Another key point in the campaign was the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which Dowdy publicly supported renewing.

In an upset, Williams lost to Dowdy in a closely fought runoff election by 912 votes. Dowdy successfully put together a coalition of rural whites and African American voters. His support of the Voting Rights Act successfully mobilized African American voters in the district and was seen as being a key factor in his victory. Dowdy continued to serve in the U.S. Congress until he decided to run for the open U.S. Senate seat in 1988 and lost to Congressman Trent Lott.

Background

District and campaigns

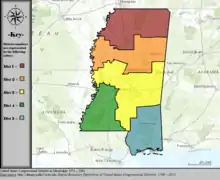

Mississippi's 4th congressional district was created in 1841, and had consistently been held by Democrats for over a century as part of the Solid South.[2] Democrats held the 4th for 90 years since the end of Reconstruction, until the election of Republican Prentiss Walker in 1965 on the back of support from Republican Presidential nominee Barry Goldwater.[2] Thad Cochran's victory in 1972 led to longer-term Republican control of the seat and cemented GOP dominance in the district for a decade. After Cochran's 1978 election to the U.S. Senate, Jon Hinson easily held the seat for Republicans in a 1978 election.

In 1981, Mississippi's 4th district contained much of the Southwestern portion of the state, just South of the Mississippi Delta. 53% of the district's registered voters came from Hinds County, where the district reached into portions of Jackson, Mississippi. 11 other mostly rural counties made up the rest of the district, including predominantly African-American Claiborne County.[3]

Hinson scandal and resignation

Prior to his election to Congress, Jon Hinson was charged in 1976 with committing an obscene act at the Marine Corps War Memorial in Washington, D.C.[5] He admitted during an August 1980 press conference to both the charge and to being one of the survivors of the 1977 fire at Cinema Follies, a theater frequented by the LGBT community.[5][6] Hinson decided to preempt his opponents from leaking the information and held the press conference, stating clearly: "I am not, never have been, and never will be a homosexual. I am not a homosexual. I am not a bisexual."[5] Hinson went on to win reelection in 1980.[4] Even though a sizable majority of the electorate opposed Hinson, the Democratic nominee Britt Singletary and Leslie B. McLemore, an African American independent, evenly split the remaining vote between them and allowed Hinson to win.[7] Hinson's vote share among white voters in the district dropped precipitously from his 1978 performance, which Mississippi reporter Bill Minor felt was "probably because of the homosexual questions."[8]

In 1981, Hinson was arrested by United States Capitol Police at the Library of Congress on the felony charge of committing oral sodomy.[5][9][10] Minority U.S. House Whip Trent Lott of Mississippi threatened to start House proceedings against Hinson, and his GOP allies in Mississippi quickly withdrew support from him.[5] U.S. Senator Thad Cochran, Mississippi GOP Chairman Clarke Reed, former Mississippi GOP Chairman Wirt Yerger, and Haley Barbour among others in the state's GOP delegation and leadership called for Hinson's resignation.[1][4][5] Democrats mostly stayed out of the fray, with Governor William Winter saying "it is not for me to judge" in regards to Hinson's scandal.[4] The person Hinson was engaged in sexual activity with when caught was African American, and the racial component made the charge harder for Hinson to overcome.[11] Leslie B. McLemore, who had run against Hinson as an independent in 1980, said, "The fact that the employee Hinson was caught with was black added insult to injury here in Mississippi."[12]

Congressman Hinson admitted himself to a Washington-area hospital "for professional care, counseling, and treatment" for a dissociative reaction, according to Hinson's administrative assistant.[13] Hinson initially pleaded not guilty to a lesser misdemeanor charge of attempted sodomy.[10] Hinson later changed his plea to "no contest" and received a 30-day suspended jail term along with a year's long probation, provided that he continued to seek medical treatment.[14] In a March letter to Governor Winter, Hinson announced he would be resigning effective April 13, 1981.[15][16] After Hinson's resignation, the election was scheduled for June 23, 1981.[17]

Later in his life, Hinson became public with his homosexuality.[18] Hinson would later go on to be an LGBT advocate in Virginia and fought against the ban on LGBT servicemembers in the military.[6][18] Hinson admitted that when he first became a U.S. Representative, he was "still closeted and into heavy denial."[18] He died of respiratory failure resulting from complications from AIDS in 1995.[6] He never returned to his native Mississippi after his resignation.[18]

Candidates

Democratic Party

- Wayne Dowdy, Mayor of McComb[19]

- Ed Ellington, State Senator[19]

- Britt Singletary, 1980 Democratic Nominee for the 4th district[19]

- Michael Herring[19]

Republican Party

- Liles Williams, businessman[19]

- Sarah Smith, inn owner[19]

- Robert Weems, former Ku Klux Klan leader[19]

Independent

- Eddie McDaniel, former Ku Klux Klan member[19]

General election

Campaign

The Republicans decided to hold a convention to nominate one candidate, nervous that a wide field of Democrats could lock out their party from being in a runoff.[20] They endorsed Liles Williams, a businessman from Clinton, at a nominating convention in April.[5][21] The Democrats chose not to endorse a particular candidate in the first round.[21] Williams emerged as the early frontrunner in the race due to his money lead and endorsements from President Ronald Reagan, Vice President George H.W. Bush and other Republican leaders.[22] U.S. Senator Thad Cochran endorsed Williams two weeks out from Election Day.[23] Labor groups in the district largely backed Democratic candidates: Wayne Dowdy was endorsed by the Mississippi AFL–CIO and both Dowdy and Britt Singletary were endorsed by the Mississippi Association of Educators.[23]

One of the largest issues in the first round was the amount of money the campaigns had on hand.[22] Democrat Michael Herring said, "I've learned that to be a viable candidate, you've got to have one speech and a lot of money to snow people on TV."[22] Williams led the fundraising with more than $206,000 raised a week before the election, leading Democrats Britt Singletary and Ed Ellington to both focus on attacking Williams's money haul for the last week of the campaign.[22] Both Singletary and Ellington attacked Williams for the amount of outside money that he received in particular, with Singletary saying, "[Williams] is not his own man."[22] Other candidates tried to carve out niches to make it to the runoff.[22][19] Robert Weems ran for the Republican nomination with the campaign slogan of "Vote Right, Vote White, Vote Weems". He was kicked out of his leadership position with the Ku Klux Klan after going to a Jackson house party attended by neo-Nazis.[lower-alpha 1][19] Singletary tried to capitalize on his role as the Democratic nominee in the 4th congressional district from 1980, and State Senator Ed Ellington attempted to use his experience in the Mississippi Legislature as a way to make the runoff.[19][22] The Clarion-Ledger felt that Williams was a lock for first place, and that the real battle was for the second slot in the runoff to face him.[24][17] Wayne Weidie with The Political Scene felt that Singletary would be the Democrat to make the runoff.[17]

The extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became a contentious issue in the campaign leading into the runoff.[25][26] Where Singletary had focused extensively on tying Hinson's scandals to Williams, Dowdy was the only major candidate from either party to support the Act's extension.[27] The other candidates in the race believed that Dowdy had "completely alienated his white base".[27]

Results

The results were seen as a strong win for the GOP and marked Williams as the favorite in the runoff.[28] The extension of the Voting Rights Act was one of the main reasons why Dowdy made it through the first round.[25] The Clarion-Ledger noted that Williams ran up respectable numbers in African American precincts and was in a strong position to gain the votes needed to win.[28] The election itself was marred by poll workers asking for social security numbers from voters, which was heavily criticized by the League of Women Voters and local residents.[29] Poll workers in Hinds County were instructed to ask for the numbers to help purge the voter rolls of inactive voters, but the County Election Commission failed to notify the public about the procedure.[29] One poll worker when asked did not know why they were collecting the social security information.[29] A District Commissioner had to go on local radio stations to stop poll workers from asking for the numbers.[29] The Election Commission and the Circuit Clerk were inundated with phone calls from irate voters throughout the day and State Senator Henry Kirksey felt that it was a violation of the Voting Rights Act.[29]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Liles Williams | 37,291 | 43.62% | |

| Democratic | Wayne Dowdy | 22,742 | 26.60% | |

| Democratic | Britt Singletary | 12,271 | 14.35% | |

| Democratic | Ed Ellington | 11,441 | 13.38% | |

| Democratic | Michael T. Herring | 611 | 0.72% | |

| Republican | Robert L. Weems | 524 | 0.61% | |

| Independent | E. L. McDaniel | 413 | 0.48% | |

| Republican | Sarah A. Smith | 194 | 0.23% | |

| Total votes | 85,487 | 100.00% | ||

| Plurality | 14,477 | 17.02% | ||

Campaign

After the first round results, Democrat Wayne Dowdy faced Republican Liles Williams in a two-week runoff campaign. In late June, Williams had raised $276,514 while Dowdy had only brought in $115,691.[31] Williams was seen as the favorite to win the runoff.[32][33] Williams ran his campaign sticking closely to President Ronald Reagan's policies – the 4th district had backed Reagan in the 1980 presidential election.[34][35] Dowdy opposed the Reagan administration's tax cuts, specifically citing its cuts to Social Security and education.[36] Letters bearing Reagan's signature were sent to 85,000 of the district's Republicans to support Williams.[37] President Reagan made a phone call that was piped through to a Republican rally. Addressing a cheering crowd, Reagan told Williams "We're waiting for you up here and need your help."[37] Dowdy criticized Williams as a "rubber stamp" for President Reagan's policies, although Dowdy avoided directly criticizing Reagan himself throughout the campaign.[38] Dowdy instead focused on local issues and couched criticism of Reagan through that lens.[39]

Another key point in the campaign was the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which Dowdy publicly supported keeping.[36] Dowdy would talk about his support for the legislation in debates when pressed, and avoided talking about the issue in his television ads.[40] However, in front of the African American community, Dowdy aggressively and publicly supported the Act.[41] Medgar Evers's niece cut a radio ad for Dowdy targeting African Americans and invoked Martin Luther King Jr.'s legacy to vote Dowdy.[37]

Dowdy challenged Williams to a series of 12 Lincoln–Douglas-style debates across the 4th district, which the Williams campaign characterized as "grandstanding".[42][43] The two eventually agreed to a televised debate on WAPT.[43] In the final stretch of the campaign, Williams continued his fundraising advantage.[44] The Clarion-Ledger and The Jackson Daily News both endorsed Williams in the closing stretch of the runoff.[45]

Results

In an upset, Wayne Dowdy won a narrow election by just 912 votes.[46][47][48][lower-alpha 2] Election turnout went past 110,000 voters for one of the largest contemporary runoff turnouts nationwide.[47] Dowdy won with a coalition of African Americans who supported his stance on the Voting Rights Act, along with rural white voters.[49] Williams ran ads attacking labor unions, which helped drive rural white voters towards Dowdy.[50] The Clarion-Ledger noted that rural and African American turnout was up past expectations, and felt this increase was responsible for Dowdy's win.[3] Dowdy credited African American voters for his win, saying they were "very, very helpful".[48] Speculation that some of Senator Ed Ellington's vote in Hinds County would shift to Williams in a runoff ended up not coming to fruition.[3] Williams did not concede defeat on Election night and decided to wait until the results could be confirmed with full accuracy.[3][47] He conceded defeat the next afternoon at a 2PM press conference once an arithmetically accurate count had been completed.[47][46]

Dowdy denied that his victory was a plebiscite on President Reagan's policies, saying that it was a "vote between two candidates" and pushed back on his race's national implications.[48][51] Dowdy explained that their campaign went to "great lengths not to run against [President Reagan]."[48] The Chairman of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee Tony Coelho called the victory a repudiation of "the idea of a Solid South for Reagan."[52] Republicans publicly attributed Williams's loss to the challenges created by Hinson's scandals.[52] The Washington Post reported, however, that Republicans in DC were concerned about the implications of losing a conservative House seat for the 1982 midterm elections.[26]

Voters were generally not asked for their social security number, although some voters in Hinds County were still asked for them.[53]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Wayne Dowdy | 55,656 | 50.41% | +21.01% | |

| Republican | Liles Williams | 54,744 | 49.59% | +10.62% | |

| Total votes | 110,400 | 100.0% | |||

| Majority | 912 | .08% | |||

| Turnout | 110,400 | ||||

| Democratic gain from Republican | Swing | 21.01% | |||

Aftermath

Liles Williams announced his candidacy in 1982 to face Congressman Dowdy in a rematch from their special election matchup.[54] Unlike in the special where Williams was the heavy favorite, Congressman Dowdy was viewed as the stronger contender for re-election while Reagan's numbers sagged nationally.[55] Dowdy was able to fend off both Williams and an African American challenger and comfortably won re-election by over 11,000 votes.[56] Congressman Dowdy continued to serve in the U.S. Congress until he decided to run for the open U.S. Senate seat in 1988 and lost to Congressman Trent Lott.[57][58]

Notes

References

- "Hinson should resign from post if charge proven, leaders say". Hattiesburg American. Associated Press. February 5, 1981. Retrieved May 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lehew, Dudley (November 4, 1964). "Prentiss Walker Now Congressman". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved March 14, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (July 8, 1981). "Surge in black, rural turnout put Dowdy over the top". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "More calls for Hinson resignation". Enterprise-Journal. Associated Press. February 6, 1981. Retrieved May 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 24, 1981). "Hinson didn't give up without a stout battle". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Estrada, Louie (July 26, 1995). "Jon C. Hinson Dies at 53". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- Busbee 2014, p. 368.

- Minor, Bill (November 16, 1980). "Fourth District 'safe seat' for Republicans". Enterprise-Journal. Retrieved August 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Saiffen, Michael (February 5, 1981). "Mississippi's Rep. Hinson Arrested On Sex Charge". The Atlanta Constitution. Retrieved May 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- United Press International (February 5, 1981). "Official Pleads Innocent to Sodomy". Fort Lauderdale News. Retrieved May 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Howard 2001, pp. 276–277.

- Harris, Art; Treyens, Cliff (June 17, 1981). "Hinson's Memory Haunts His Mississippi District". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

- "Hospital admits Hinson". Enterprise-Journal. Associated Press. February 6, 1981. Retrieved May 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Neuman, Johanna; Treyens, Cliff (May 29, 1981). "Hinson put on probation in sex case". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Stickney, Ken (1981). "Hinson to quit Congress, tells Governor". The New York Times. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- Neuman, Johanna (March 14, 1981). "Hinson resigns effective April 13". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved May 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Weidie, Wayne W. (June 4, 1981). "Fourth Congressional district race close as June 23 election nears". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Jon Hinson, 53, Congressman And Then Gay-Rights Advocate". The New York Times. Associated Press. 1995. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- Putnam, Judy; Treyens, Cliff (June 21, 1981). "Candidates offer varied experience and philosophies to the 4th District". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved May 18, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Nash & Taggart 2009, pp. 126–127.

- "Democratic chairman raps GOP selection". Hattiesburg American. Associated Press. April 7, 1981. Retrieved June 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 21, 1981). "Cash clash ups ante in 4th District". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved May 30, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 9, 1981). "Thad Cochran says he backs Williams". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 21, 1981). "Candidates circle wagons, attack bulging budgets". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Glaser 1998, pp. 47–48.

- Nash & Taggart 2009, p. 127.

- Glaser 1998, p. 47.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 24, 1981). "Williams had broad support in GOP win". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved May 30, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Putnam, Judy; Pendergrast, Loretta (June 24, 1981). "Voters gripe at I.D. requests". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "MS District 4 - Special Election Primary". Our Campaigns. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 27, 1981). "Williams outspends Dowdy in campaign's dollar battle". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 27, 1981). "Williams floods 4th district during summer rainstorm". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tuesday's runoff election to choose new Congressman". Hattiesburg American. Associated Press. July 5, 1981. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hampton, David (May 17, 1981). "4th District Race Feels the Reagan Effect". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 9, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Barone & Ujifusa 1988, p. 653.

- Putnam, Judy (July 5, 1981). "Dowdy propels campaign with zest". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Glaser 1998, p. 49.

- Glaser 1998, p. 50.

- Glaser 1998, pp. 49–50.

- Glaser 1998, p. 48.

- Glaser 1998, pp. 48–49.

- Putnam, Judy (June 26, 1981). "Dowdy challenges foe to series of debates". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 27, 1981). "Williams, Dowdy set tentative TV debate". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Treyens, Cliff (June 26, 1981). "Williams gets $6,100 per day during 11-day period". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- The Editorial Board (July 5, 1981). "We back Williams". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Putnam, Judy (July 10, 1981). "Dowdy sworn in; final tally shows 912-vote margin". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Democrat Wins Mississippi Seat in Congress with Blacks' Help". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Associated Press. July 8, 1981. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Reaganite fails to stop Mississippi Democrats". Mansfield News Journal. Associated Press. July 8, 1981. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Glaser 1998, pp. 50–52.

- Krane & Shaffer 1992, p. 86.

- Treyens, Cliff (July 9, 1981). "Dowdy takes seat in Capitol today". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Glaser 1998, p. 52.

- Cilwick, Ted; Zimmerman, Martin (July 8, 1981). "Turnout high, procedures smooth at precincts". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hampton, David (May 23, 1982). "Williams delivery charges Dowdy is inconsistent". The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Minor, Bill (October 28, 1982). "Stronger GOP support dies". Columbian-Progress. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Williams concedes, declines comment". The Clarion-Ledger. November 4, 1982. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Stewart, Steve (November 9, 1988). "Dowdy: Senate race may be my last". Enterprise-Journal. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- DOWDY, Charles Wayne, (1943 - ) Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

Sources

- Barone, Michael; Ujifusa, Grant (1988). The almanac of American politics, 1984. National Journal. ISBN 0-89234-031-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nash, Jere; Taggart, Andy (2009). Mississippi Politics: The Struggle for Power, 1976-2008. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1604733578.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krane, Dale; Shaffer, Stephen D. (1992). Mississippi Government and Politics: Modernizers Versus Traditionalists. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 080327758X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howard, John (October 10, 2001). Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226354709.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glaser, James M. (1998). Race, Campaign Politics, and the Realignment in the South. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300077238.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Busbee, Wesley, Jr. (December 31, 2014). Mississippi: A History. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1118755901.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Kuzenski, John C.; Moreland, Laurence W.; Steed, Robert P. (2001). Eye of the Storm: The South and Congress in an Era of Change. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0275971147.