1996 Japanese general election

A general election took place in Japan on October 20, 1996. A coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party, New Party Sakigake and the Social Democratic Party, led by incumbent Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto of the LDP won the most seats.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

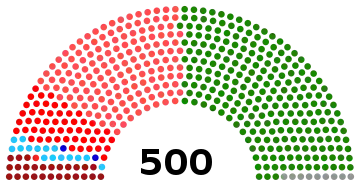

All 500 seats to the House of Representatives of Japan 251 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 59.65% ( | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This was the first election under the new election rules established in 1993. Before this election, each district was represented by multiple members, sometimes from the same party, causing intra-party competition. Under the new rules, each district nominated one representative, who would represented a wide range of interests for their district. A separate party-list was introduced for voters to choose their favored party (in addition to votes for individual candidates) as a way to more accurately approximate the seats in the House of Representatives of Japan to the actual party votes in an effort to achieve more proportional representation.

With only a single member in each district, this change allows for additional district-wide benefits. This is opposed to the preceding multi-member district wherein each representative appeals to either policy or geographic-based benefits or narrow set of interests in their constituencies without consideration for party interest.

Background

The 41st general election of members of the House of Representatives took place on October 20, 1996. General election for the House of Representatives was not supposed to be due until July 1997, but on 27 September 1996, Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto dissolved the parliament, thus calling for a snap-election. This move to call premature elections had been widely expected as the Prime Minister's last effort to sustain power in the midst of a controversial sales hike.[1]

The last election in July 1993 ended the 38-year-long rule of Japanese politics by the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), and no party had a majority in parliament since then. During the following three years, Japan had a succession of four coalition governments, which hampered effective government policy making and implementation. Furthermore, the constant replacement also slowed down the process of economic recovery. There were expectations that the 1996 election would restore political stability.[2]

The election was the first election under the new electoral system established in 1993. The multi-member constituency was replaced with single member districts, and separate party list seats chosen proportionately.[2] Prior to 1993, each district was represented by multiple members, sometimes from the same party, leading to severe corruption and intra-party competition. The latter consequence resulted in defects within the LDP and creations of opposition parties that advocated for a new electoral system. As a result, a new system emerged, adopting both the single member district (SMD) competition and proportional representation (PR).[2] Under the new system, each district has only one representative portraying a wide range of interests for his or her district. A separate party-list was introduced for voters to choose their favored party (in addition to votes for individual candidates) as a way to more accurately approximate the seats in the House of Representatives of Japan to the actual party votes in an effort to achieve more proportional representation.

Contesting Parties

Ruling Coalition

The ruling coalition was the coalition formed between the LDP, New Party Sakigake and Social Democratic Party of Japan.

The LDP was led by Ryutaro Hashimoto, who became Prime Minister of Japan after the election. The party was pro-business at the time, thus its campaign focused on policies countering Japanese economic slump.[1]

The New Party Sakigake was led by Shoichi Ide, a political party formed as a defect of LDP on 22 June 1993. In September 1996, Sakigake and Japan Socialist Party (JSP) politicians who did not support their respective parties alliances with the LDP broke away to found the Democratic Party. The party was later dissolved in 2002.[3]

Japan Socialist Party (JSP) was led by Takako Doi. The party formed a coalition government with the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) from 1994 to January 1996. The LDP coaxed the Social Democrats into this coalition by forgoing the Prime Minister title. Consequently, the office of Prime Minister was given to JSP's leader, Murayama Tomiichi.[4] He was the 81st Prime Minister of Japan.

Other Parties

Other opposition parties to the ruling coalition came from the right-wing New Frontier Party (NFP) led by Ichiro Ozawa. It was formed in December 1994 by defectors of the Japan Renewal Party, Komeito, Democratic Socialist Party and a couple of other small groups.[5]

Another rival party was the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party was formed officially in September 1996 with Yukio Hatoyama and Naoto Kan as co-leaders. The move for formation began in June 1996 when Hatoyama announced his idea of organizing a third force in Japanese politics against the LDP and the New Frontier Party. The idea was supported by his brother Kunio then a member of the New Frontier Party and many members of the Social Democratic Party of Japan, but opposed by leaders of the Social Democratic Party of Japan and New Party Sakigake who had been discussing the organizational merger of the two parties.[2]

Campaign Issues

Prior to the election, there was a frenzy of creation and destruction of parties, and the public's interest in politics was on the decline. However, the few campaign issues that were of the public's interest included the electoral reforms, potential raise in consumption tax, and how the large coalitions will play out. From the perspective of the voters, the most important issue was the potential raise in consumption tax. According to scholar Ichiro Miyake, voter's opinion possession rate, party position perception rate, personal importance cognition rate of “tax increase” exceeded that of “regime change.”[6]

Liberal Democratic Party Manifesto

In the LDP manifesto, administrative reform is given top priority over any other campaign issues. While reflecting on the past 50-years of administrative policy prioritizing production and supply with strong centralization and bureaucratization as an effective method in simultaneously achieving economic growth and tackling social inequality, the LDP admits this system is “at a deadlock” considering the situation regarding women, increasing urban-rural disparities and the issue of low-birth rate. To tackle these issues, the LDP introduced the “Hashimoto Administrative Reform Vision (橋本行革ビジョン)”, which included changes such as;[7]

- “Slimming” the Power of government

- Deregulation of the economy

- Decreasing the power of bureaucrats

- Reduction of income/residence tax, while raising consumption tax to 5%

- Tackling deficit financing, etc.

Hashimoto reform vision strays far from previous LDP reforms, notably under Nakasone.[8] While previous reforms focused on the privatization of public corporations and abstained from challenging the power of the bureaucrats, Hashimoto marched towards shifting bureaucratic power to the hands of political leaders, effectively giving policy-making power to the Prime Minister's Office. His ambition was, without doubt, met with strong resistance from the bureaucrats, who stood almost unchallenged at the center of public life during the high growth period. Despite his short tenure, he was not forced out of office before he had gotten a law outlining the reforms passed.

Hashimoto sought to focus power in the hands of the prime minister and subsequently political leadership by combining former bureaucratic agencies (twenty-three ministerial level organizations to twelve) and replacing the Prime Minister's Office with a new Cabinet Office.[8] The implementation of such changes allowed the prime minister, for the first time ever, the authority by law to initiate basic policymaking, the power which previously was solely allocated only to powerful bureaucracies. Additionally, the new Cabinet Office was composed with advisory councils, appointed from both within and outside the government, to the prime minister on economic and fiscal policies. Hashimoto, furthermore, used exactly the same method by which the powerful bureaucracies maintained their authority. If the economic bureaucracy in the 1960s and 1970s imposed on the Prime Minister's office and the Diet their own members as a method to secure supremacy over policy-making decision,[9] then Hashimoto also increased the power of political leaders by replacing vice ministers with Diet members whom he trusted.[8]

New Frontier Party Manifesto

The leader of the opposing coalition NFP's manifesto was directly against that of the LDP, introducing the “5 contracts with the people (国民との5つの契約)”, aimed at “revitalizing the lives of citizens” for the coming 21st century. The 5 promises were as follows.[7]

- Keeping the consumption tax at 3% and an ¥18 trillion tax cut based on reducing the income and residence tax in half

- Administrative reform, decentralization, and abolition of regulations for a reduction of ¥20 trillion in national and regional expenses

- Reducing utility charges by 20-50%

- Guaranteeing pension and nursing care to eliminate anxiety of old age

- Excluding bureaucratic dependence and holding politicians accountable

Democratic Party Manifesto

The Democratic party introduced the following "7 major issues" as the backbone of their manifesto.[7]

- Enforcement of political and administrative reform

- Promotion of civic activities and creation of a civic-centric society

- Implementation of economic structural reform and improvement of infrastructure for creative industrial activities

- Restructuring of the social security system and realization of symbiotic welfare society

- Fundamentally review and reform of public works

- Development of autonomous active diplomacy and promotion of non-military international cooperation

- Creating and implementing a future-oriented fiscal reconstruction plan

Communist Party Manifesto

The Communist party's manifesto is centered around three key issues: stopping the consumption tax raise, the abolishment of US military bases in Okinawa following the abandonment of the US-Japan security treaty, and to increase social security and welfare.[7] In the manifesto, the party gives an outlook on a national outlook, summarized in three parts;

- Democratically regulating large enterprises and prioritizing the lives of citizens

- To protect the Constitution (with an emphasis on Article 9), contribute to the peace of Asia and the world

- To maintain and cherish freedom and democracy

Social Democratic Party Manifesto

The Social Democratic Party proposed three slogans - "Yes, let's go with SDP", "A new dynamism, SDP", and "What can only be done by the SDP" - and fought the election. The following 5 manifestos were considered the cornerstones of the election.[7]

- National security for creating a peaceful Japan and the world, with respect to the spirit of the Constitution and reflections and lessons learnt from history

- Creating a simple and efficient government with rich autonomy, with fundamental administrative reform that breaks down the adhesion between the government and the private sector

- Creating prosperous lifestyles with economic structural reforms that bring out competitive effects, with emphasis on the environment, safety, and employment

- Undertaking fiscal structural reforms while fundamentally reviewing taxes and finances, to create a high-quality welfare society

- Preserving human dignity and human rights, for a coexisting society that is gentle and caring for men and women

Results

Voter turnout fell below 60% for the first time in recorded history (59.65%). The last election was the lowest of all previous elections, at 67.26%. The ruling coalition (LDP, SDP, NPH) gained a majority seating in the House of Representatives with 256 seats, but the SDP and NPH lost most of their seats for forming a coalition with LDP. While the opposing coalition (NFP, DPJ, JCP, and others) gained 235 seats, their total local constituency votes were larger than the ruling coalition, at 53.45%.

| |||||||||

| Alliances and parties | Local constituency vote | PR block vote | Total seats | +/− | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes[13] | % | Seats | Votes | % | Seats | ||||

| Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) | 21,836,096 | 38.63% | 169 | 18,205,955 | 32.76% | 70 | 239 | ||

| Social Democratic Party (SDP) | 1,240,649 | 2.19% | 4 | 3,547,240 | 6.38% | 11 | 15 | ||

| New Party Harbinger (NPH) | 727,644 | 1.29% | 2 | 582,093 | 1.05% | 0 | 2 | ||

| Ruling coalition | 23,804,389 | 42.11% | 175 | 22,335,288 | 40.19% | 81 | 256 | ||

| New Frontier Party (NFP) | 15,812,326 | 27.97% | 96 | 15,580,053 | 28.04% | 60 | 156 | ||

| Democratic Party (DPJ) | 6,001,666 | 10.62% | 17 | 8,949,190 | 16.10% | 35 | 52 | ||

| Japan Communist Party (JCP) | 7,096,766 | 12.55% | 2 | 7,268,743 | 13.08% | 24 | 26 | ||

| Democratic Reform League | 149,357 | 0.26% | 1 | 18,884 | 0.03% | 0 | 1 | ||

| Others | 1,155,108 | 2.04% | 0 | 1,417,077 | 2.55% | 0 | 0 | ||

| Opposition parties | 30,215,223 | 53.45% | 116 | 33,233,907 | 59.81% | 119 | 235 | ||

| Independents | 2,508,810 | 4.44% | 9 | – | 9 | ||||

| Totals | 56,528,422 | 100.00% | 300 | 55,569,195 | 100.00% | 200 | 500 | (electoral reform: -11 18 vacant seats) | |

| Turnout | 59.65% | 59.62% | – | ||||||

| Allotted number of Seats | Number of Candidates | Number of Voters | Voter Turnout (Overall) | Voter Turnout (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |||

| Single Member Districts | 300 | 1261 | 97,680,719 | 47,385,036 | 50,295,683 | 58,262,930 | 27,970,063 | 30,292,867 | 59.7 | 59.0 | 60.2 |

| Proportional Representation | 200 | 566 (808) | 58,239,414 | 27,960,034 | 30,279,380 | 59.6 | 59.0 | 60.2 | |||

Post-Election

Criticisms

Three aspects of the new electoral system drew serious criticisms after the first election in 1996, two of which had been curbed through law enactments.[15] Immediately after the 1996 election, double candidacy became a major concern of the media and the most controversial aspect of the new system. In the new system, candidates are allowed to transfer between tiers, running for both the single-member district (SMD) and the proportional representation (PR) tier. This provision was met with harsh commentary from the press who criticized the system as a method through and around which incompetent candidates move in their search for a Diet position. Candidates who ‘died’ in the SMD were then to be ‘revived’ in the PR as ‘zombie Diet members.’[8] Despite no major laws were enacted to address the controversy, press complaints declined with the 2000 electoral law revision in which candidates who failed to collect at least one-tenth of the effective vote in an SMD election are immediately disqualified.[15]

On another note, the 1996 election saw higher incidence of by-elections.[15] Under the old system, by-elections were held only if two seats became vacant; however, the number of by-elections rose rapidly in the SMD system. Between 1947 and 1993, there were only eighteen incidences of by-election; whereas in the first two mixed-member elections, there were twelve by-elections. The Diet responded to this unanticipated consequence by holding by-elections on the same day twice a year for both upper and lower houses. It is important to know that by-elections can have interesting political consequences such as that of a minority party looking to win one or more seats in order to earn official party status or the balance of power in a minority or coalition situation.

The new electoral system, furthermore, did not produce what was initially hoped – a two-party parliamentary system.[15] In spite of different views in regard to the number of seats being reduced, a major referendum was approved, thus deflating the original 200 seats allocated to the PR tier to 180 before the second election.

Role of the Policy Affairs Research Council

The double candidacy system preserved incentives for personal votes and, thus, also incentives for individual candidates to maintain their Koenkai and for new candidates to form their own.[8] Unrevised campaign restrictions meant that candidates running in the SMD tier were still permitted to mobilize votes by means of a provision of constituency services and benefits to their district.[15] Meanwhile, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) imposed “best loser rule” for resurrection encouraged candidates to gain a certain number of personal votes in the SMD tier to ‘qualify’ for Proportional Representation tier.[8]

The Policy Affairs Research Council (PARC), originally a strategic instrument for vote-gaining in the single non-transferable vote system (SNTV), could still be used to gain votes in the new election system.[8] In the old system, PARC was used by candidates to distinguish themselves amongst fellow same-party rivals. To win in a multiple-seats constituency, it was important for candidates to hold expertise and influence in a policy-sector in the district they were running for. This is not to say that under the new electoral system, candidates had less need for specialization because of the increasing diversity of their smaller constituency. Those running in the PR tier needed to increase party vote, as such found it necessary to specialize in order to serve a large-scale and more diverse audience across an extensive geographical area. Consequently, the PARC was modified to provide representatives with information on many fields of policy.

Use of Coalition

In the first election of 1996, the LDP relied on the strategy of coalition to oust the ruling Japan Socialist Party (JSP) from power. Later on, coalition became "the only one way of getting back into power."[16] Under the new system of one representative per district, the LDP forge coalitions with different parties to gain a majority in the Diet. After the 1993 election, the LDP remained the largest party in the Diet, hence the Japan Socialist Party had no choice but to enter in a coalition with the LDP. This arrangement proved as a gateway to death for the JSP, whom repudiated many of its defining principles, namely the anti-Self Defense Forces and anti-US alliance stances, in exchange for prime-minister's office. Core leftist supporters of the JSP rebuked the coalition and the JSP's leaders remained unimpressed with the deal, as policymaking, the main instrument of power, was in the hands of the LDP. As a result, the JSP fell apart soon after.[16]

Coalition further proved to be instrumental to LDP prolonging power in further elections until 2009. After the coalition with the JSP fell apart, the LDP turned to the Liberal Party led by Ozawa Ichiro a leader of one of the new parties that was formed from a defection of the LDP, now merged with the Democratic Party (DPJ). This coalition, similarly, did not last long. It was the coalition with the Komeito after which proved enduring and strategic until the 2009 election.[16]

Post-2009 and until present, however, coalition strategy remains inextricable from electoral success. Coalition with Komeito still proves strategic, as Komei continues to instruct supporters to vote for LDP candidates in the SMD tier in exchange for greater power in the coalition.[17] Komei's support arguably contributed greatly to LDP's landslide win in the 2012 and 2014 elections. The statistics of the 2012 election verifies the uniqueness of the LDP-Komei coalition. In that election, Komei redirected 10.34 percent of the SMD vote it could have won to the LDP, allowing for overwhelming vote differential between DPJ and the LDP to emerge. If the Komei's vote had gone to the DPJ, the LDP and DPJ gap in share of the vote in the SMD tier would not have been significant.[17]

Koenkai

Although the significance of Koenkai had diminished as compared to pre-reform, the Koenkai withstood the electoral reform fairly well. The electoral reform initially hoped to relegate the role of the Koenkai by moving politicians away from their original electoral district in which they had invested years cultivating personal networks. In theory, this tactic should prompt candidates to rely on the party branch and party label for electoral success instead of personal networks.[8] Yet, the scholars Krauss and Pekkanen show that politicians, in spite of such incentive, concentrated on spreading their Koenkai to the new district.[8] Since the very first 1996 election, there was little evidence that party branches were replacing Koenkai in the assistance of daily activities, electoral mobilization and campaign funding.

Nevertheless, the Koenkai did diminish in strength; however, not because of the increasingly party-centered system. Rather, voters are becoming progressively less interested in joining kōenkai and instead become a floating or an independent voter, despite the politicians’ efforts in providing benefits.[8]

Withering Factional Influence

Factional influence, the endemic corruption that plagued the SNTV system, seems to be similarly on progressive decline.[8] The incorporation of a PR system has helped shift the previous solely candidate-centred to an increasingly party-centred system, what the previous Prime Minister Miki Takeo had hoped to accomplish earlier on.[18] By 2005, the number of representatives elected on the LDP PR list who were not also dual listed dropped to twenty-six from forty-nine in the 1996 election.[8]

The Diet also passed a campaign finance bill that allowed for greater public financial assistance of campaigns and simultaneously imposed severe restrictions on donations to individual politicians or factions.[15] Distribution of money now has to go through political parties, while responsibility for illegal campaign activities are more strictly monitored. Individual Diet members who carry out illegal campaign activities are now subjected to prosecution by the courts, including a possibility of being banned from election.[15]

There has also been a tendency of younger Diet members to be less loyal to their faction leaders. A notable case is Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi’s effort to reduce faction's power in cabinet formation and party leader selection. Koizumi has made it almost a de facto rule that national popularity be the basis of leadership selection. The Mori faction to which Koizumi himself belongs, for instance, won twice the party presidential primaries as a result of Koizumi's popularity.[15]

Enhanced Authority of the Prime Minister

The new advisory councils within the Cabinet Office later proved to be instrumental for succeeding prime ministers in their quest for policy-making authority. Prime Minister Koizumi well maneuvered the Councils to exert greater political leadership. Furthermore, the Councils made sure to maintain their stronghold by providing the cabinet with both political and support staff.[8]

See also

- Japanese General Election, 1993

- Japanese General Election, 2000

- Liberal Democratic Party

- New Party Sakigake

- Japan Socialist Party

- Democratic Party (Japan, 1996)

- Komeito

- New Frontier Party

- Social Democratic Party

- Single non-transferable vote

- Proportional Representation (PR)

- Single-member district

- Koenkai

- Ryutaro Hashimoto

References

- Inter-Parliamentary Union, 1996. Japan Parliamentary Chamber: Shugiin - Elections held in 1996. [online] Available at: http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/arc/2161_96.htm

- Tabusa, Keiko (1997). "The 1996 General Election in Japan". The Australian Quarterly. 69 (1): 21–29. doi:10.2307/20634762. JSTOR 20634762.

- L., Curtis, Gerald (1999). The logic of Japanese politics : leaders, institutions, and the limits of change. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231502540. OCLC 50321999.

- Christen, R., n.d. Liberal-Democratic Party of Japan. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Liberal-Democratic-Party-of-Japan [Accessed 17 December 2017].

- 1960-, Shinoda, Tomohito (2013-09-24). Contemporary Japanese politics : institutional changes and power shifts. New York. ISBN 978-0231528061. OCLC 859182680.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- MIYAKE, Ichiro (1999-02-28). "Incomplete Policy Voting". Japanese Journal of Electoral Studies. 14. doi:10.14854/jaes1986.14.50. ISSN 0912-3512.

- Manifesto Project. 1996 House of Representatives Election (1996年衆議院選挙). 慶應義塾大学大学院政策・メディア研究科曽根泰教研究室, http://www.pac.sfc.keio.ac.jp/manifesto/senkyo/1996hr.html. Accessed 18 Dec. 2017.

- S., Krauss, Ellis (2011). The rise and fall of Japan's LDP : political party organizations as historical institutions. Pekkanen, Robert. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801449321. OCLC 732957153.

- 1931-2010., Johnson, Chalmers (1982). MITI and the Japanese miracle : the growth of industrial policy, 1925-1975. Rogers D. Spotswood Collection. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804712069. OCLC 8310848.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), Statistics Department, Long-term statistics Archived 2015-02-15 at the Wayback Machine, chapter 27: Public servants and elections, sections 27-7 to 27-10 Elections for the House of Representatives

- Inter Parliamentary Union

- "Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications". Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- Fractional votes rounded to full numbers

- Bureau of Statistics. 衆議院議員総選挙の定数,立候補者数,選挙当日有権者数,投票者数及び投票率. Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/chouki/27.htm. Accessed 18 Dec. 2017.

- The politics of electoral systems. Gallagher, Michael, 1951-, Mitchell, Paul, 1964-. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2005. ISBN 0199257566. OCLC 68623713.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The Routledge handbook of Japanese politics. Gaunder, Alisa, 1970-. London: Routledge. 2011. ISBN 9780415551373. OCLC 659306335.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Andrew, Oros (2017). Japan's security renaissance : new policies and politics for the twenty-first century. New York. ISBN 9780231172615. OCLC 953258554.

- L., Curtis, Gerald (1988). The Japanese way of politics. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231066813. OCLC 16805800.