Arkansas Delta

The Arkansas Delta is one of the six natural regions of the state of Arkansas. Willard B. Gatewood Jr., author of The Arkansas Delta: Land of Paradox, says that rich cotton lands of the Arkansas Delta make that area "The Deepest of the Deep South."[1]

Bottom: The Delta Cultural Center in Helena-West Helena is operated by the Department of Arkansas Heritage to preserve and interpret the culture of the region.

| Part of a series on |

| Regions of Arkansas |

|---|

|

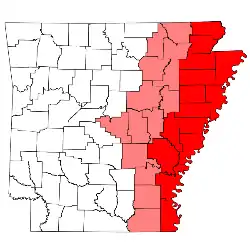

The region runs along the Mississippi River from Eudora north to Blytheville and as far west as Little Rock. It is part of the Mississippi embayment, itself part of the Mississippi River Alluvial Plain.[2] The flat plain is bisected by Crowley's Ridge, a narrow band of rolling hills rising 250 to 500 feet (76 to 152 m) above the flat delta plains. Several towns and cities have been developed along Crowley's Ridge, including Jonesboro.[3] The region's lower western border follows the Arkansas River just outside Little Rock down through Pine Bluff. There the border shifts to Bayou Bartholomew, stretching south to the Arkansas-Louisiana state line.

While the Arkansas Delta shares many geographic similarities with the Mississippi Delta, it is distinguished by its five unique sub-regions: the St. Francis Basin, Crowley's Ridge, the White River Lowlands, the Grand Prairie and the Arkansas River Lowlands (also called "the Delta Lowlands"). Much of the region is within the Mississippi lowland forests ecoregion.

The Arkansas Delta includes the entire territories of 15 counties: Arkansas, Chicot, Clay, Craighead, Crittenden, Cross, Desha, Drew, Greene, Lee, Mississippi, Monroe, Phillips, Poinsett, and St. Francis.[4] It also includes portions of another 10 counties: Jackson, Lawrence, Prairie, Randolph, White, Pulaski, Lincoln, Jefferson, Lonoke and Woodruff counties.[5]

Geology

The Delta is subdivided into five unique sub-regions, including the St. Francis Basin, Crowley's Ridge, the White River Lowlands, the Grand Prairie, and the Arkansas River Lowlands (also called "the Delta Lowlands").

Grand Prairie

The underlying impermeable clay layer in the Stuttgart soil series that allowed the region to be a flat grassland plain initially appeared to stunt the region's growth relative to the rest of the Delta. But in 1897, William Fuller began cultivating rice, a crop that requires inundation, with great success. Rice cultivation still features prominently in the region's economy and culture today. Riceland Foods, the world's largest rice miller and marketer, is based in Stuttgart, Arkansas on the Grand Prairie.[6]

History

Early history and frontier Arkansas

In the earth's history, after the Gulf of Mexico withdrew from what was Missouri, many floods occurred in the Mississippi River Delta, building up alluvial deposits. In some places the deposits measure 100 feet (30 m) deep.[7]

The region was occupied by succeeding cultures of indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Some cultures built major earthwork mounds, with evidence of mound-building cultures dating back more than 12,000 years. These mounds have been preserved in three main locations: the Nodena Site, Parkin Archaeological State Park, and Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park.[8]

French explorers and colonists encountered the historic Quapaw people in this region, who lived along the Arkansas River and its tributaries. The first European settlement in what became the state was the French trading center, Arkansas Post.[9] The post was founded by Henri de Tonti while searching for Robert de La Salle in 1686.[10] The commerce in the area was initially based on fishing and wild game. The fur trade and lumber later were critical to the economy.[11]

Early European-American settlers crossed the Mississippi and settled among the swamps and bayous of east Arkansas. Frontier Arkansas was a rough, lawless place infamous for violence and criminals.[12] Settlers, who were mostly French and Spanish colonists, generally engaged in a mutually beneficial give-and-take trading relationship with the Native Americans. French trappers often married Quapaw women and lived in their villages, increasing their alliances for trade.

Around 1800 United States settlers gradually entered this area.[7] In 1803 the US acquired the territory from France by the Louisiana Purchase.[13] As settlers began to acquire and clear land, they encroached on Quapaw territory and traditional hunting and fishing practices. The two cultures had divergent views of property. Relations deteriorated further after the 1812 New Madrid earthquake, which was felt throughout the region and taken as a portent. Some Native Americans considered the earthquake to be a sign of punishment for trading with the European settlers.[14]

The beginning point of all subsequent surveys of the Louisiana Purchase was placed in the Arkansas Delta near Blackton. In 1993 this site was named a National Historic Landmark and later preserved as Louisiana Purchase State Park. A granite marker, accessible via a boardwalk through a swamp, marks the starting point of the survey.[15]

Territorial era through statehood

During the antebellum era, American settlers used enslaved African Americans as laborers to drain swamps and clear forests along the river to cultivate the rich alluvial plain. They began to develop cotton plantations, which produced the chief commodity crop of the region.[7]

After achieving territorial status in 1819, Arkansas reneged on an 1818 treaty with the Quapaw. Territory officials began removing the Quapaw from their fertile homeland in the Arkansas delta. The Quapaw had inhabited lands along the Arkansas River and near its mouth at the Mississippi River for centuries.

The invention of the cotton gin had made short-staple cotton profitable, and the Deep South was developed for cotton cultivation. It grew well in fertile delta soils. Settlers took these fertile lands for agriculture and pushed the Quapaw south to Louisiana in 1825-1826. The Quapaw returned to southeast Arkansas by 1830, but were permanently relocated to Oklahoma in 1833 under the Indian Removal Act passed by Congress.[16]

High cotton prices encouraged many planters to concentrate on cotton as a commodity crop, and the large plantations were dependent on slave labor. The plantation economy and a slave society were developed in the Arkansas Delta,[7] with black slaves forming the majority of the population in these counties. This region developed political interests different from outlying areas where yeomen farmers were concentrated.

Many African Americans were brought into the Delta throughout the early-to-mid-19th century through the domestic slave trade, transported from the Upper South. The counties with the largest populations of slaves by 1860 included Phillips (8,941), Chicot (7,512), and Jefferson (7,146). Prior to the U.S. Civil War, numerous Delta counties had majority-black and enslaved populations.[7] As Arkansas was developed later than some other areas of the Deep South, its wealthy planters did not construct as many grand plantation mansions as in other states. The American Civil War ended that antebellum period.[7]

The Civil War resulted in destruction to the river levees and other property damage. Expensive investment was required to repair the levees. The region's continued reliance on agriculture kept wages low, and the cotton market did not recover. Many freedmen stayed in the area, working by sharecropping and tenant farming as a way of life.

20th century, through Civil Rights era

Like other states of the former Confederacy, the state legislature of Arkansas passed laws to disenfranchise most blacks and many poor whites, in an effort to suppress Republican voting. It passed the Election Law of 1891, which required secret ballots, and standardized ballots, eliminating many illiterate voters. It also created a centralized election board, providing for consolidation of Democratic political power. Having reduced voter rolls, in 1892 the Democrats passed a poll tax amendment to the constitution, creating another barrier to voter registration for struggling white and black workers alike, many unable to pay such fees in a cash-poor economy. These two measures caused sharp declines in the number of African-American and white voters; by 1895 no African-American members were left in the General Assembly. The Republican Party was hollowed out, and the farmer-labor alliance collapsed. Most blacks were kept off the rolls and out of electoral politics for more than six decades, until after Congressional passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, although a concerted effort in the 1940s increased voter registration.

Social tensions rose in the area after World War I, as black veterans pushed for better conditions. Unlike other mass riots of Red Summer 1919, when whites attacked blacks in numerous northern and midwestern cities because of labor and social competition, the Elaine Race Riot, now known as the "Elaine Massacre", was the result of rural forces. It occurred near Elaine, Arkansas in the Delta, where local planters were trying to discourage the formation of an agricultural union among blacks. White mobs killed an estimated 237 blacks; five whites were killed in the unrest.

The area suffered extensively during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, which put tens of thousands of acres underwater, caused extensive property damage, and left many people homeless.

In the mid-1930's, large cotton plantations, under stress because of the Great Depression, benefited from the New Deal's Agricultural Adjustment Act, which paid them to leave fields fallow, thereby raising the price of cotton by reducing the supply. The effect was devastating for sharecroppers and tenant farmers. In response, two young Socialists, advised by Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party, formed the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union. They organized racially integrated meetings throughout the Arkansas Delta and signed up over 2,000 members. By 1935, the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union had over 10,000 members in 80 chapters. The union mounted a cotton pickers strike in the Delta in 1935, and after months marked by violence, the cotton pickers returned to the fields with considerably higher wages. But the union's power was greatly diminished by 1939.[17]

In the 1940s the mechanized cotton picker was introduced into regional agriculture. This led to a significant decline in demand for manual labor. During World War II, the defense industry in California and other western locations attracted many African-American workers from Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas in a second wave of the Great Migration, resulting in a marked population decrease in the Delta. The lack of jobs continued to cause a decline. Charles Bowden of National Geographic wrote, "By 1970 the sharecropping world was already disappearing, and the landscape of today—huge fields, giant machines, battered towns, few people—beginning to emerge."[7]

Music

The Arkansas Delta is known for its rich musical heritage. While defined primarily by its deep blues/gospel roots, it is distinguished somewhat from its Mississippi Delta counterpart by more intricately interwoven country music and R&B elements. Arkansas blues musicians have defined every genre of blues from its inception, including ragtime, hokum, country blues, Delta blues, boogie-woogie, jump blues, Chicago blues, and blues-rock. Eastern Arkansas' predominantly African-American population in cities such as Helena, West Memphis, Pine Bluff, Brinkley, Cotton Plant, Forrest City and others has provided a fertile backdrop of juke joints, clubs and dance halls which have so completely nurtured this music. Many of the nation's blues pioneers were either born in the Arkansas Delta or lived in the region.

Today the region hosts several blues events throughout the year, culminating in the Arkansas Blues and Heritage Fest. The festival attracts an average of about 85,000 people per day over its three-day run; it is rated in the top 10 music events in the nation by festivals.com.

Gospel music, the mother of Delta Blues, is enshrined in the lives and social fabric of residents. Many popular Delta artists in all other genres had their start singing or playing in church choirs and quartets. Given the historic racism and entrenched segregation in the Delta, the African-American church and, by extension, its music, have taken on a central role in the lives of residents. African-American gospel music's roots are deep in the Delta. Unlike the blues, which has been historically dominated by men throughout the Delta, women established a pioneering role in gospel music. From the quartet traditions that dominate south Arkansas, to the classic and contemporary solo artists who have found national prominence in the east, gospel music in the Delta has made and continues to make a significant mark on the cultural landscape.

The Arkansas Delta's country music roots have depth, with legendary performers coming from the area. While more geographically dispersed throughout the region, these artists represent the very best in country genres, including bluegrass, rockabilly, folk music, and alternative country. This music expresses the long-standing relationship between blues and country. As young country musicians continue to develop in the Delta, they continue to help the genre grow and evolve.

R&B music has also had a presence as an outgrowth of the strong blues and gospel traditions. The East Central Delta area has produced a small number of talented and influential R&B artists.

Arkansas's blues Influence, shares a rich heritage with Mississippi and Memphis, Tennessee. Arkansas was home to numerous blues masters, who are held in high esteem by newer generations learning blues history. Arkansas blues artists influenced decades of pop culture music by such artists as Muddy Waters, Little Milton, B.B. King, Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Joe Bonamassa, Stevie Ray Vaughan, George Harrison and the Rolling Stones. Some of the most notable Arkansas Delta born or affiliated blues/gospel artists include: Albert King, Big Bill Broonzy, Sippie Wallace, George Thomas, Bobby Rush, Eb Davis, Frank Frost, George Harmonica Smith, Hollis Gillmore, Howlin’ Wolf, Hubert Sumlin, James Cotton, Johnny Shines, Junior Walker, Sonny Boy Williamson II, Junior Wells, Larry Davis, Louis Jordan, Luther Allison, Michael Burks, Robert Johnson, Robert Lockwood Jr., Al Bell, J. Mayo "Ink" Williams, Robert Nighthawk, Sam Carr, Houston Stackhouse, James Cotton, Johnny Taylor, Shirley Brown, William "Petey Wheatstraw" Bunch, Son Seals, Luther Allison, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Al Green, and others. Country/ Americana artists Johnny Cash and Levon Helm were also born and raised in the Arkansas Delta.

Today

The Arkansas Delta economy is still dominated by agriculture. The main commodity crop is cotton; other crops include rice and soybeans. Catfish farming has been developed as a new source of revenue for Arkansas Delta farmers, along with poultry production.

The Delta has some of the lowest population densities in the American South, sometimes fewer than 1 person per square mile. Slightly more than half the population is African American, reflecting their deep history in the area. Eastern Arkansas has the most cities in the state with majority African-American populations. Urbanization and the shift to mechanization of farm technology during the past 60 years has sharply reduced jobs in the Delta. People have followed jobs out of the region, leading to a declining tax base. This hampers efforts to support education, infrastructure development, community health and other vital aspects of growth. The region's remaining people suffer from unemployment, extreme poverty, and illiteracy.

The Delta Cultural Center in Helena seeks to preserve and interpret the culture of the Arkansas Delta along with the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff's University and Cultural Museum. The Arts and Science Center for Southeast Arkansas in Pine Bluff is charged with highlighting and promoting works of Delta artists.

The ivory-billed woodpecker, which had not been sighted since 1944 and is believed to be extinct, was reportedly seen in a swamp in east Arkansas in 2005.

Principal cities

Higher education

Highways

- Interstate 40 - From Brinkley to West Memphis

- Interstate 55 - From West Memphis to Blytheville

- U.S. Highway 278

- U.S. Highway 49

- U.S. Highway 61

- U.S. Highway 62

- U.S. Highway 63

- U.S. Highway 64

- U.S. Highway 65

- U.S. Highway 165

- U.S. Highway 67

- U.S. Highway 70

- U.S. Highway 79

- U.S. Highway 82

See also

Notes

- Williard B. Gatewood Jr. and Jeannie M. Whayne, eds. (1996). The Arkansas Delta: Land of Paradox. University of Arkansas Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-61075-032-5.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gatewood and Whayne 1993, p. 3.

- Smith, Richard M. (1989). The Atlas of Arkansas. The University of Arkansas Press. p. 19. ISBN 1557280479.

- "The Arkansas Delta - The Region". Arkansas Delta Byways. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- Gatewood and Whayne (1993), N.Pag..

- Lancaster, Guy (December 16, 2011). "Grand Prairie". Retrieved August 28, 2016.

- Bowden, Charles. "Return to the Arkansas Delta". (Archive) National Geographic. November 2012. Retrieved on June 3, 2013.

- Early, Ann M. (November 5, 2011). "Indian Mounds". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. The Butler Center. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- Smith, Darlene (Spring 1954). "Arkansas Post". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 13 (1): 120. doi:10.2307/40037965. JSTOR 40037965.

- Mattison, Ray H. (Summer 1957). "Arkansas Post: Its Human Aspects". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 16 (2): 119. doi:10.2307/40018446. JSTOR 40018446.

- Gatewood and Whayne 1993, pp. 8-9.

- Gatewood and Whayne 1993, pp. 9-10.

- Arnold et al (2002), p. 78.

- Arnold et al (2002), p. 89.

- Baker, William D. (September 16, 1991). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Louisiana Purchase Survey Marker / Louisiana Purchase Initial Point Site" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved July 31, 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - White, Lonnie J. (Autumn 1962). "Arkansas Territorial Indian Affairs". Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 21 (3): 197. doi:10.2307/40018929. JSTOR 40018929.

- Naison, Mark D. (1996). "The Southern Tenant Farmers' Union and the CIO". In Lynd, Staughton (ed.). "We are all leaders": the alternative unionism of the early 1930s. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 103–116. ISBN 0252065476. OCLC 247133530. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

References

- Arnold, Morris S.; DeBlack, Thomas A.; Sabo III, George; Whayne, Jeannie M. (2002). Arkansas: A narrative history (1st ed.). Fayetteville, Arkansas: The University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-724-4. OCLC 49029558.

- Gatewood, Willard B; Whayne, Jeannie (1993). The Arkansas Delta: A Land of Paradox. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-287-0.

- Dollins, Mike. Blues Guitar News: A listing of Arkansas Blues Legends and Blues Highway 49 History.

Further reading

- Ecoregions of the Mississippi Alluvial Plain - Environmental Protection Agency

External links

- Delta Rivers Nature Center in Pine Bluff

- Rural Development Heritage Initiative-Preservation

- Lakeport Plantation--Arkansas's only Antebellum Plantation Home on the Mississippi River

- Cultural Museum of the Arkansas Delta in Helena, Arkansas

- UAPB Museum devoted to the History of the University and the Delta