Politics and government of Arkansas

The State government of Arkansas is divided into three branches: executive, legislative and judicial. These consist of the state governor's office, a bicameral state legislature known as the Arkansas General Assembly, and a state court system. The Arkansas Constitution delineates the structure and function of the state government. Since 1963, Arkansas has had four seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Like all other states, it has two seats in the U.S. Senate.

Political party strength

Reflecting the state's large evangelical population, the state has a strong socially conservative bent. The 1874 Arkansas Constitution established this as a right to work state (a provision then directed against union organizers), in the 21st century its voters passed a ban on same-sex marriage with 75% voting yes, and the state is one of a handful with legislation on its books banning abortion in the event Roe v. Wade (1973) is overturned.

Democrats

Since the late 19th century, Southern Democrats of Arkansas have traditionally had an overwhelming majority of registered voters in the state. At that time, they consolidated their power and achieved effective disfranchisement of African Americans (and Republican) voters by passage of the Election Law of 1891 and a poll tax amendment in 1892, which also dropped many poor white Democrats from the rolls. Together these also suppressed the coalition of Republican and farmer-labor parties, which had threatened the Democrats. Assessing fees to register and vote resulted in many poor people being dropped from voter rolls. The Election Law set up secret ballots and standardized ballots in progressive reforms that also made voting more complicated and effectively closed out illiterate voters. It set up a state election board and officials, putting power into the hands of the Democratic Party, rather than county workers. Voter rolls declined for both black and white voters. By 1895, there were no longer any African-American representatives in the state house.[1] African Americans were closed out of the political system for decades.

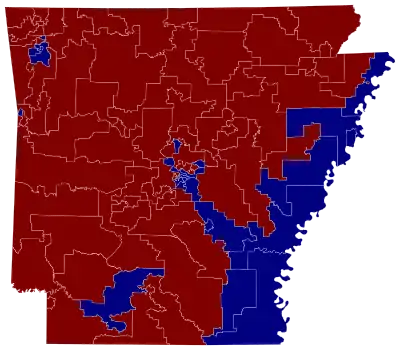

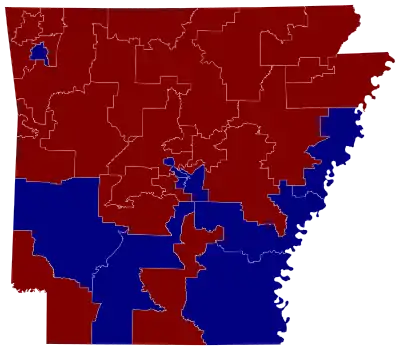

In the 20th and 21st centuries, Arkansas Democrats have tended to be more conservative than their national counterparts, particularly in areas outside metropolitan Little Rock. Traditionally having strength in most areas outside the Northwest and North Central parts of the state, in the 21st century Democrats in Arkansas predominate along the Mississippi River in the East, in central Little Rock, and around Pine Bluff and the areas south of there along the Louisiana border.

Republicans

Historically Republicans in the state were based in the northwestern areas, long a supporter of the Unionist cause in the Civil War. These were areas of yeomen farmers in the antebellum years. Planters and major slaveholders lived in the Delta area along the Mississippi River and tended to ally with the Democratic Party. As noted above, disenfranchisement of African Americans and consolidation of power by the Democrats left the Republicans nearly powerless. They concentrated on developing patronage positions.[2]

In 1966, Republican John Paul Hammerschmidt won a U.S. House seat from this northwestern area, the first Republican from Arkansas to be elected to Congress since after Reconstruction.[2] He held the seat until 1992, when he retired. What was more surprising, that year multi-millionaire Winthrop Rockefeller was elected to the governorship. A 1950s migrant from New York, he was joined by Republican Maurice "Footsie" Britt, a World War II hero elected as lieutenant governor. Unlike in other parts of the South at the time, Rockefeller's coalition was based on "progressive Democrats and newly enfranchised black voters." They also elected him in 1968. Rockefeller faced resistance from the conservative Democratic legislature. In 1970 the Democrats put up their own progressive candidate and defeated Rockefeller. Rockefeller died in 1973, which weakened the emerging Republican Party. It was 1978 before Ed Bethune was elected to Congress as the second Republican from the state; he served three terms from central Arkansas.[2]

It was not until the late 20th century that more white conservatives in Arkansas began to shift from the Democratic to the Republican Party. In 1989 Democratic Congressman Tommy Robinson announced his shift to the Republican Party, an indication of change.[2] The party continues to be strongest in the northwestern part of the state, due to historic conditions of that area, particularly in Fort Smith and Bentonville, as well as North Central Arkansas around the Mountain Home area. In the latter area, Republicans have been known to get 90 percent or more of the vote.

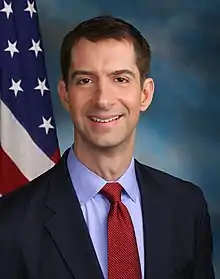

While the rest of the state used to be more Democratic, since the late 20th century Republicans have attracted members from the Little Rock suburbs, the southwest (especially Texarkana), and the northeast around Jonesboro. Tim Hutchinson, elected in 1996, was the first Republican U.S. Senator from Arkansas since Reconstruction. As an indication of increasing Republican strength in the state, Republicans John Boozman and Tom Cotton were elected to the U.S. Senate in 2010 and 2014 respectively, giving the state all-Republican representation in the Senate.

History since 1992

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 62.40% 760,647 | 34.78% 423,932 |

| 2016 | 60.57% 684,872 | 33.65% 380,494 |

| 2012 | 60.57% 647,744 | 36.88% 394,409 |

| 2008 | 58.72% 638,017 | 38.86% 422,310 |

| 2004 | 54.31% 572,898 | 44.55% 469,953 |

| 2000 | 51.31% 472,940 | 45.86% 422,768 |

| 1996 | 36.80% 325,416 | 53.74% 475,171 |

| 1992 | 35.48% 337,324 | 53.21% 505,823 |

| 1988 | 56.37% 466,578 | 42.19% 349,237 |

| 1984 | 60.47% 534,774 | 38.29% 338,646 |

| 1980 | 48.13% 403,164 | 47.52% 398,041 |

| 1976 | 34.93% 268,753 | 64.94% 499,614 |

| 1972 | 68.82% 445,751 | 30.71% 198,899 |

| 1968* | 31.01% 189,062 | 30.33% 184,901 |

| 1964 | 43.41% 243,264 | 56.06% 314,197 |

| *State won by George Wallace of the American Independent Party, at 38.65%, or 235,627 votes | ||

Arkansas had the distinction in 1992 of being the only state in the country to give the majority of its vote to a single presidential candidate: native son Bill Clinton. Every other state's electoral votes were won by pluralities of the vote among the three candidates. Since the turn of the 21st century, Arkansas voters have tended to support Republicans in presidential elections.

Former First Lady of the United States and First Lady of Arkansas, Hillary Clinton, ran for the United States Senate. Even though she was a native of Chicago and had lived in Arkansas with her husband, Bill Clinton, she eventually ran from New York. [3]

The state voted for John McCain in 2008 by a margin of 20 percentage points, making it one of the few states in the country to vote more Republican that year than it had in 2004. (The others were Louisiana, Tennessee, Oklahoma and West Virginia.)[4]

Even while supporting Republican candidates for president, Arkansas voters continued to favor Democrats for statewide offices. In 2006, Democrats were elected to all statewide offices in a Democratic sweep that included regaining the governorship. By 2014, however, Republicans had won all statewide offices, all Congressional seats, and dominated both chambers of the state legislature.

Law and government

As in the national government of the United States, political power in Arkansas is divided into three main branches: Executive, Legislative, and Judicial.

Each officer's term is four years long. Office holders are term-limited to two full terms plus any partial terms before the first full term. Arkansas governors served two-year terms until a referendum lengthened the term to four years, effective with the 1986 general election. Statewide elections are held two years after presidential elections.

Some of Arkansas's counties have two county seats, as opposed to the usual one seat. The arrangement dates back to when travel was extremely difficult in the state. The seats are usually on opposite sides of the county to serve residents within easier traveling distances. Although travel conditions have improved, there are few efforts to eliminate the two seat arrangement where it exists, since the county seat is a source of pride (and jobs) to the cities involved.

Arkansas is the only state to specify by law the pronunciation of its name (AR-kan-saw).[lower-alpha 1]

Article 19 (Miscellaneous Provisions), Item 1 in the Arkansas Constitution is entitled "Atheists disqualified from holding office or testifying as witness," and states that "No person who denies the being of a God shall hold any office in the civil departments of this State, nor be competent to testify as a witness in any Court." In 1961, the United States Supreme Court in Torcaso v. Watkins (1961), held that a similar requirement in Maryland was unenforceable because it violated the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the US Constitution. The latter amendment, per current precedent, makes the federal Bill of Rights binding on the states. As a result, this 'religious test' provision has not been enforced in modern times. It would be overturned if challenged in court.

Executive

The current Governor of Arkansas is Asa Hutchinson, a Republican, who was elected on November 4, 2014.[5][6][7] Arkansas also elects the lieutenant governor and several cabinet-level positions: secretary of state, attorney general, treasurer, auditor, and land commissioner.[8] The governor appoints qualified individuals to lead various state boards, committees, and departments.

In Arkansas, the lieutenant governor is elected separately from the governor and can be from a different political party.[9]

Following reorganization in 2019, state government is subdivided into fifteen departments, each led by a cabinet-level official (titled secretary):

- Department of Agriculture

- Department of Commerce

- Department of Corrections

- Department of Education

- Department of Energy & Environment

- Department of Finance and Administration

- Department of Health

- Department of Human Services

- Department of Inspector General

- Department of Labor and Licensing

- Department of the Military

- Department of Parks, Heritage, and Tourism

- Department of Public Safety

- Department of Transformation and Shared Services

- Department of Veteran Affairs

Legislative

The Arkansas General Assembly is the state's bicameral bodies of legislators, composed of the Senate and House of Representatives. Elections in the Arkansas Senate are staggered such that half the body is up for re-election every two years. Since the late 20th century, the Senate has 35 members from districts of approximately equal population. These districts are redrawn decennially with each US census. The entire state senate was up for reelection in 2012. Arkansas voters elected a 21-14 Republican majority in the Senate.

House districts are redistricted by the Arkansas Board of Apportionment. Following the 2012 elections, Republicans gained a 51-49 majority in the House of Representatives.[10]

Following the 2014 elections, an amendment to the Arkansas Constitution was approved that expanded legislative term limits to 16 years total in either the Senate and House of Representatives. Prior to this, Senators were limited to two four-year terms and Representatives were limited to three two-year terms.

The Republican Party majority status in the Arkansas State House of Representatives following the 2012 elections is the party's first since 1874 during the Reconstruction era. Democrats regained control of the state house and suppressed black and Republican voters. At the turn of the century, the legislature passed a new constitution and laws disenfranchising most African Americans and establishing Jim Crow. African Americans were closed out of the political system for many decades. The shift of white conservatives from the Democratic to the Republican Party took place more gradually in Arkansas than some southern states. It was 2012 before the Republican Party re-established control of the state legislature.[11]

Composition of the Arkansas legislature

Arkansas's legislature is controlled by the Republican Party, which gained the majority in both houses following the 2012 general election.

The Arkansas House of Representatives

| Affiliation | Members | |

|---|---|---|

| Republican | 76 | |

| Democratic | 24 | |

| Seat Vacant | 0 | |

| Total | 100 | |

The Arkansas Senate

| Affiliation | Members | |

|---|---|---|

| Republicans | 26 | |

| Democrats | 9 | |

| Seat Vacant | 0 | |

| Total | 35 | |

State judiciary

Arkansas's judicial branch has five court systems: Arkansas Supreme Court, Arkansas Court of Appeals, Circuit Courts, District Courts and City Courts.

Most cases begin in district court, which is subdivided into state district court and local district court. State district courts exercise district-wide jurisdiction over the districts created by the General Assembly. Local district courts are presided over by part-time judges who may also privately practice law. Twenty-five state district court judges preside over 15 districts. The legislature has committed to establishing more districts in 2017 to accommodate growth in population.

There are 28 judicial circuits of Circuit Court, with each containing five subdivisions: criminal, civil, probate, domestic relations, and juvenile court. The jurisdiction of the Arkansas Court of Appeals is determined by the Arkansas Supreme Court. There is no right of appeal from the Court of Appeals to the high court. However, the Arkansas Supreme Court can review Court of Appeals cases upon application by either a party to the litigation, upon request by the Court of Appeals, or if the Arkansas Supreme Court believes the case should have been assigned to it. The twelve judges of the Arkansas Court of Appeals are elected from judicial districts to renewable six-year terms.

The Arkansas Supreme Court was established in 1836 by the Arkansas Constitution as the court of last resort in the state. It is composed of seven justices elected to eight-year terms. The court's decisions can be appealed only to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Federal representation

Arkansas's two U.S. Senators are elected at large:

- Senior U.S. Senator John Boozman (R)

- Junior U.S. Senator Tom Cotton (R)

Arkansas has four congressional districts. There were 5th, 6th, 7th, and at-large districts, but they were eliminated in 1963, 1963, 1953, and 1885, respectively. U.S. House of Representatives:

- Arkansas's 1st congressional district includes the Crowley's Ridge region and most of the Arkansas Delta – Rep. Rick Crawford (R).

- Arkansas's 2nd congressional district covers the region generally called Central Arkansas, including Little Rock – Rep. French Hill (R).

- Arkansas's 3rd congressional district covers northwest Arkansas, including the Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers Metropolitan Area and Fort Smith metropolitan area – Rep. Steve Womack (R)

- Arkansas's 4th congressional district covers South Arkansas and the Ouachita Mountains – Rep. Bruce Westerman (R).

| Representatives' Political Persuasion – the 113th Congress | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR District | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | Class 1 Senator | Class 2 Senator |

| Representative | Rick Crawford | French Hill | Steve Womack | Bruce Westerman | John Boozman | Tom Cotton |

| Conservative Score[12] | 81 | 79 | 81 | TBD | 60 | 81 |

| Liberal Score[12] | 5 | 2 | 5 | TBD | 0 | 0 |

Gallery of members of U.S. Senate

Senior Senator John Boozman

Senior Senator John Boozman Junior Senator Tom Cotton

Junior Senator Tom Cotton

Gallery of members of U.S. House of Representatives

Notes

- The name Arkansas has been pronounced and spelled in a variety of fashions. The region was organized as the Territory of Arkansaw on July 4, 1819, but the territory was admitted to the United States as the state of Arkansas on June 15, 1836. The name was historically /ˈɑːrkənsɔː/, /ɑːrˈkænzəs/, and several other variants. The people of Arkansas call themselves either "Arkansans" or "Arkansawyers". In 1881, the Arkansas General Assembly passed the following concurrent resolution, now Arkansas Code 1-4-105 (official text Archived 2011-09-24 at the Wayback Machine):

Whereas, confusion of practice has arisen in the pronunciation of the name of our state and it is deemed important that the true pronunciation should be determined for use in oral official proceedings. And, whereas, the matter has been thoroughly investigated by the State Historical Society and the Eclectic Society of Little Rock, which have agreed upon the correct pronunciation as derived from history, and the early usage of the American immigrants. Be it therefore resolved by both houses of the General Assembly, that the only true pronunciation of the name of the state, in the opinion of this body, is that received by the French from the native Indians and committed to writing in the French word representing the sound. It should be pronounced in three (3) syllables, with the final "s" silent, the "a" in each syllable with the Italian sound, and the accent on the first and last syllables. The pronunciation with the accent on the second syllable with the sound of "a" in "man" and the sounding of the terminal "s" is an innovation to be discouraged.

Residents of the state of Kansas often pronounce the Arkansas River as /ɑːrˈkænzəs ˈrɪvər/, in a manner similar to the common pronunciation of the name of their state.

References

- Success=true&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Branam, Chris M. “Another Look at Disfranchisement in Arkansas, 1888–1894”, Arkansas Historical Quarterly 69 (Autumn 2010): 245–262, via JSTOR

- Jay Barth, "Republican Party", Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture, 2014

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/national/2016/07/22/from-spouse-to-senator.

- See image.

- "Winners in '06 Governors races" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- "Arkansas.gov Administration page for Governor". Dwe.arkansas.gov. March 16, 2007. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- "Governor Terms and Term Limits" (PDF). Snelling Center for Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 7, 2009. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- Arkansas Code 7-5-806.

- "Office of Lieutenant Governor". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. The Pryor Center. February 28, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- Cooke, Mallory. "Republicans Take Control of Arkansas House, Senate". KFSM-TV. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- "Arkansas Senate flips; first time since Reconstruction". The Courier. November 7, 2012. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

- "Liberal Vote Scores, Cosponsorship Ratings and Contact Information for Members of the House of Representatives in the 112th Congress of 2011-2012". That's My Congress. 2012. Missing or empty

|url=(help)

Further reading

- Barnes, Kenneth C. Who Killed John Clayton? Political Violence and the Emergence of the New South, 1861–1893. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998.

- Graves, John William. Town and Country: Race Relations in an Urban-Rural Context, Arkansas 1865–1905. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1990.

- Kousser, J. Morgan. The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880–1910. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974.

- Ogden, Frederic D. The Poll Tax in the South. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1958.

- Perman, Michael. Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

- Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South, 1877–1913. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1951.

External links

See also

- Arkansas Congressional Districts

- Arkansas General Assembly

- Democratic Party of Arkansas

- Governor of Arkansas

- List of politics by U.S. state

- List of United States Senators from Arkansas

- Political party strength in Arkansas

- Republican Party of Arkansas

- Split-ticket voting

- United States Congressional Delegations from Arkansas