Culture of Arkansas

The culture of Arkansas is a subculture of the Southern United States that has come from blending heavy amounts of various European settlers culture with the culture of African slaves and Native Americans. Southern culture remains prominent in the rural Arkansas delta and south Arkansas. The Ozark Mountains and the Ouachita Mountains retain their historical mount. Arkansans share a history with the other southern states that includes the institution of slavery, the American Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow laws and segregation, the Great Depression, and the Civil Rights Movement.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of the United States of America |

|---|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

United States portal |

On a more abstract level, Arkansas's culture can be seen and heard in its literature, music, sports, film, television and art. Arkansas is known for such authors as John Gould Fletcher, John Grisham, Charlaine Harris, and Maya Angelou; for musicians and bands such as Johnny Cash and Charlie Rich; for interest in football, hunting and fishing; for the films and television shows filmed in the state and the actors and actresses from Arkansas; and for the art created by Arkansans and inspired by the state of Arkansas.

People

The people of Arkansas are stereotyped both by their manners and for being highly religious. Language in Arkansas is a combination of several different sub-dialects of Southern American English found across the state. The state's culture is also influenced by her economy. Finally, Arkansas's cuisine is integral to her culture with such foods as barbecue, traditional country cooking, fried catfish and chicken, wild duck, rice, purple hull peas, okra, apples, tomatoes and grits being part of the people of Arkansas's diet and economy.

Reputation of Arkansas

The stereotype, which is frequently characterized by a lazy, rural, poor, banjo-playing, racist, cousin-marrying hick is commonly applied to Arkansas and its residents. Arkansas's hillbilly reputation, and its citizen's defensiveness on the subject, are a very important piece of Arkansas's culture. Many Arkansans defend the state from this image, yet others embrace it. The Old State House Museum currently houses an exhibit regarding the state's reputation.[1]

Origins

The present day image of Arkansas has evolved from early diary entries written by the first visitors to the state. During the frontier period, many were exploring the new western extents of the United States and sending their findings back east. Henry Schoolcraft, George William Featherstonhaugh, and Henry Merrill were some of Arkansas's earliest detractors.[2] Their accounts described the state as a backwater full of savages and outlaws. The travelers also commented on the self-sufficient nature and the wide range of survival skills possessed by the denizens of frontier Arkansas.[3] This characterization was common among frontier states, but since geography prevented travelers from passing through Arkansas in subsequent years, the early commentary held in the public consciousness.[4]

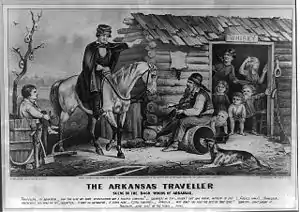

The image continued to grow when southwestern humor publications played on the backwardsness of poor whites, especially in hill country.[5] The most enduring icon of Arkansas's hillbilly reputation is The Arkansas Traveller, a painted depiction of a folk tale from the 1840s.[6] The tale involves gubernatorial candidate Archibald Yell and his party of politicians becoming lost in the Ozarks on a campaign trip and resorting to asking for directions at a squatter's cabin. The man continues to play his banjo and evade the traveler's questions before feeding the party and allowing them to stay the night.[6] Although intended to represent the divide between rich southeastern plantation Arkansas planters and the poor northwestern hill country, the meaning was twisted to represent a Northerner lost in the Ozarks on a white horse asking a backwoods Arkansan for directions.[7] The legend continued to grow, including a play named Kit, the Arkansas Traveler and the publication of a humor journal named the Arkansaw Traveler.

Racial component

Another component of Arkansas's image is a history of racism and racial violence. Arkansas is given the social stigma which is common to the former slave states of the Confederacy. The presence of the Ku Klux Klan following the Civil War and events such as the Elaine Race riot continued to affirm the state's reputation for racism. The Little Rock Nine crisis at Central High School in Little Rock defined the state as resistant to racial integration for many years and it also renewed the stereotype for many. The Little Rock Nine crisis and similar events are often the only references to the state in history books, thus forming the opinions of many and perpetuating the state's negative reputation.[8]

Southern dialect in Arkansas

—Quote exhibiting the assumed link between accent and education, Mike Royko, 1992.[9]

Many Arkansans speak with a Southern dialect or accent, although it is generally characterized as an Upper South accent similar to that of neighboring Oklahoma and Texas in contrast to the accent of the Deep South.[10] The accent is an important method for Arkansans to identify themselves with the Southern culture, and is commonly used by those from other regions to link Arkansas to the illiterate, uneducated Southern stereotype.[11]

Anecdotes of Northern accent-holders disrespecting and dismissing the intelligence of those with Southern dialects are largely the result of popular culture's portrayal of the South, including Gone With the Wind, The Beverly Hillbillies, and Deliverance.[12] Rosina Lippi, author and holder of a PhD in linguistics, has commented that Northerners use the link to ignorant, lazy Southerners to denigrate the South.[11] Since Southerners are a group connected by a common culture and history rather than a race defined by ethnic characteristics, the North uses the Southern accent to appeal to stereotypes[11] of the region that are otherwise uncomfortable topics, such as racism.[13] The belittlement of Southern dialect speakers has been effective[11] to the point at which classes on losing one's Southern accent are offered for those looking to move and work in the North.[14]

Food and drink

Meats, poultry, fish and seafood

Arkansas lies among three well-known barbecue regions: Memphis, Texas, and Kansas City, and has a mixture of styles across the state rather than a distinct "Arkansas style". This combination is sometimes known as the "Mid-South style".[15] Much of the Arkansas Delta was settled by migrants from Tennessee and Virginia, who brought their barbecue traditions to Arkansas. Independence Day barbecues are described in Arkansas as early as 1821, prior to statehood.[16] In the Delta, barbecues were community events, eventually coopted by politicians seeking to meet voters. Antebellum pit barbecues in Arkansas were often established around trenches dug in a clearing in the woods, filled with oak and hickory burned down to hot coals, tended by slaves, and served whatever animals the community was willing to offer, including cows, pigs, sheep, goats, chickens, deer, wild turkey and possums.[17] Slaves also hosted their own barbecues on plantations, though the practice was significantly curbed after Gabriel's Rebellion and the Nat Turner Rebellion.[18]

The smoked meat tradition was very important to early settlers to preserve meat, as the smokehouse was one of the Arkansas settler's most important outbuildings.[19] Hog hunts and pig roasts were community events in early Arkansas.[20]

Popular restaurant dishes include pulled pork and chicken sandwiches, brisket, and ribs served with traditional side dishes. BBQ chicken is especially prominent in the Ozarks region, which has a long history of poultry production. Some BBQ restaurants, such as McClard's Bar-B-Q in Hot Springs,[21] are also known for hot tamales (often called "delta style tamales" in the Arkansas delta).[22]

Other traditional meat entrees include hamburger steak with gravy and onions and fried dishes (chicken fried steak, fried chicken, catfish).

Twice cooked chicken, potato salad, purple hull peas, corn bread, and iced tea

Chicken fried steak, corn nuggets, purple hull peas

BBQ beef sandwich and smoked beans

Shrimp and potatoes

Ribs, potato salad, baked beans, and bread

Tamales

Smothered chicken, mashed potatoes and gravy, macaroni and cheese and roll

Fried chicken

BBQ sandwich and baked beans

BBQ beef platter with baked beans and coleslaw  Tamales platter

Tamales platter

Side dishes and condiments

Louis Jordan of Brinkley, Arkansas, was known as the King of the Jukebox from the late 1930s to the early 1950s. Several of his songs reference traditional dishes served in Arkansas, including charting singles "Beans and Corn Bread" and "Cole Slaw (Sorghum Switch)". Traditional side dishes to accompany entrees include corn bread, greens, potato dishes (baked potato or French fries), macaroni and cheese, salads (fruit, garden, Jello, pasta or potato), coleslaw, corn, and a variety of fried vegetables (such as okra or pickles).

Cheese dip, sometimes referred to as queso, was created at Mexico Chiquito in North Little Rock, Arkansas. Little Rock hosts the annual World Cheese Dip Championship, and restaurants across Central Arkansas offer special recipes to diners.[23] The Arkansas Department of Parks & Tourism's Cheese Dip Trail has 19 stops across the state. Arkansas cheese dip won a blind taste test against Texas-style queso among United States Senate Republicans in 2016, following a feature about Arkansas's cheese dip heritage in The Wall Street Journal.[24]

Sweets

Early Arkansas settlers relied on honey bee honey and sorghum for sweetening food, with store-bought sugar or candy used only rarely. Settlers would "course the bees" to their hive, retrieve the hive to their farm, and store the bees in a bee gum in a black gum tree.[25] Almost every early farmer had a patch of sorghum to make sorghum molasses for use as a sweetener when honey ran out.[26] Fall sorghum harvests led to meetings at the community sorghum mill, which doubled as community events.[27]

Sugar maples can be found in the hills and hollers of the Ozarks, where people collect sap (although commonly called "water" in the area) from the trees in a method similar to Vermont or Canada. Although dependent upon weather conditions, January and February are generally the only window when this type of sap harvesting is feasible due to the warm Arkansas climate. This water is harvested and boiled, traditionally in large cast iron pots, usually requiring approximately 43 US gallons (160 L) of water to produce 1 US gallon (3.8 L) of syrup. For many in the Ozarks, this is a family tradition involving camping in the woods among the trees or other family gatherings.[28]

Fried pickles

Governor Asa Hutchinson (left) and US Representative Mike Ross (second from left), competes in the annual watermelon eating competition in Hope

Fried catfish, purple hull peas, and hot water cornbread

Fried catfish, mashed potatoes and gravy, and greens

Arts

Architecture

The architecture of Arkansas varies wildly, whether one is looking across the street, across the city, or across the state. Architecture can be divided into two main branches: folk houses and structures in a traditional sense and buildings built in a specific style to follow a trend or explore a new style.

The historical timeline of architecture in Arkansas is similar to that of the nation. Throughout the 1800s three styles vied for dominance: French Colonial, Federal, and Greek Revival, however many structures built during this period do not exist today. Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Second Empire became en vogue during the late 1800s. Later structures near the turn of the century frequently modeled the Queen Anne and Romanesque Revival styles. Charles L. Thompson became very active in Arkansas in the late 1800s and into the next century. His firm designed over 2,000 buildings in the state and was at the forefront of architecture in Arkansas for many years. Today 143 of his firm's older works are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[29]

A variety of architectural styles became popular in Arkansas in the 20th century, including American Craftsman, Classic Revival, Colonial Revival, Prairie School, Tudor Revival, and later Art Moderne, and Art Deco. E. Fay Jones began producing works of organic architecture, including Thorncrown Chapel and Mildred B. Cooper Memorial Chapel and several homes in northwest Arkansas. Most recent buildings in Arkansas have been constructed in modern style.

Early settlers began by fabricating log structures and shacks using available materials.

Literature

Early literature about Arkansas shortly after statehood in 1836 describes Arkansas as a savage backwater populated by lazy farmers and unintelligent slaves. Arkansas was also frequently the subject of Southwest humor pieces, a genre in which exaggeration and hyperbole is used for comedic effect. Some of these images stuck in the public conscience, and are partially responsible for the "Arkansas hillbilly" stereotype still commonly applied today. Literature from Arkansas natives often bears the mark of the state's varied geography. The culture of rural Arkansas towns is reflected in works like I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou (based in Stamps, Arkansas) and John Grisham's A Painted House (based in Black Oak, Arkansas). The University of Arkansas Press is the state's largest publisher.

Music

Performing arts

The state of Arkansas has a few theaters for the performance arts, including the Walton Arts Center in Fayetteville, the Arkansas Public Theatre in Rogers, the Robinson Center in Little Rock, and the King Opera House in Van Buren. The Arkansas Arts Council supports a group of touring performers as well as providing financial support for the performing arts.[30] Arkansas Repertory Theatre, based in Little Rock, is the state's largest non-profit theater company. Northwest Arkansas also has a regional theater company, TheatreSquared, the region's only year-round theater. TheatreSquared has received recognition from the American Theatre Wing and focuses on youth arts education in addition to their 100+ performances annually.

Little Rock hosts the Arkansas Repertory Theatre as well as the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra and Ballet Arkansas. The Arkansas Arts Center in downtown Little Rock is the state's premier arts center, including permanent works by Rembrandt, Pablo Picasso, and Edgar Degas.[31] Across the Arkansas River, the Argenta Arts District contains a community theatre as well as studios and galleries.[32]

Folk music and traditional Ozark performances are available at Ozark Folk Center State Park in Mountain View. Folk dances, including square dances and hoedowns, were a dominant cultural force across early Arkansas.[33]

Museums

The museums in Arkansas display and preserve the culture of Arkansas for future generations. From fine art to history, Arkansas museums are available throughout the state. The most popular museum in Arkansas is Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, financed by Alice Walton, with 604,000 visitors in 2012, its first year.[34] The museum is near the Downtown Bentonville and includes walking trails and educational opportunities in addition to displaying over 450 works covering five centuries of American art.[35] Other art museums in Arkansas include the Arkansas Arts Center in Little Rock and South Arkansas Arts Center in El Dorado.

History museums interpret the history of the state for Arkansans and tourists, and are located across the state. The National Park Service (NPS) maintains sixteen properties in the state, as well as Arkansas Post National Memorial, which preserves the history of the first European settlement in Arkansas. The NPS also offers historical museums at Bathhouse Row, Central High School National Historic Site, Fort Smith National Historic Site, and Pea Ridge National Military Park.

The Department of Arkansas Heritage operates four different museums in Arkansas including the Delta Cultural Center in Helena-West Helena and the Historic Arkansas Museum, the Old State House (Little Rock) and the Mosaic Templars Cultural Center all in Little Rock. The Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism operates the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources in Smackover. The department also runs eight historic state parks: Hampson Archeological Museum State Park, Jacksonport State Park, Lower White River Museum State Park, Davidsonville Historic State Park, Historic Washington State Park, Parkin Archeological State Park, Powhatan Historic State Park, and Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park. History museums such as the Grant County Museum in Sheridan, Headquarters House Museum in Fayetteville, Lakeport Plantation near Lake Village, and the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale seek to preserve pieces of local and regional significance.

Sports

Sports are an integral part of the culture of Arkansas, and its residents enjoy participating and spectating various events throughout the year. One of the oldest sports in Arkansas is hunting. The large supply and cheap production of guns following the Civil War made it possible for many Arkansans to hunt with other men in camps. These hunting parties often roamed across the wilderness, eating well and imbibing frequently. The state created the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission in 1915 to regulate and enforce hunting.[36] Today a significant portion of Arkansas's population participates in hunting animals such as duck and deer. Tourists also come to the state to hunt game. Fishing has always been popular in Arkansas. The sport and the state have benefited from the creation of reservoirs across Arkansas. Following the completion of Norfork Dam, the Norfork Tailwater and the White River have become a destination for trout fishers. Several smaller retirement communities such as Bull Shoals, Hot Springs Village, and Fairfield Bay have flourished due to their position on a fishing lake. The Buffalo National River has been preserved in its natural state by the National Park Service and is frequented by fly fishers annually.

Football, especially collegiate football, has always been important to Arkansans, primarily because of a lack of a top level professional sports team. College football in Arkansas began from humble beginnings. The University of Arkansas first fielded a team in 1894 when football was a very dangerous game. Many attempts to regulate violence and use of ringers plagued the sport early on. Calling the Hogs is a cheer that shows support for the Razorbacks, one of the two FBS teams in the state. High school football also began to grow in Arkansas in the early 20th century. Over the years, many Arkansans have looked to the Razorbacks football team as the public image of the state, despite their general mediocrity. Following the Little Rock Nine integration crisis at Little Rock Central High School, Arkansans looked to the successful Razorback teams in the following years to repair the state's reputation. Although the University of Arkansas is based in Fayetteville, the Razorbacks have always played at least two games per season at War Memorial Stadium in Little Rock in an effort to keep fan support in central and south Arkansas. Arkansas State University joined the Football Bowl Subdivision along with the University of Arkansas in 1992 after playing in lower divisions for decades. However, the two schools have never played each other, due to the University of Arkansas' policy of not playing intrastate games.[37] Six of Arkansas's smaller colleges play in the Great American Conference, with University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff playing in the Southwestern Athletic Conference and University of Central Arkansas competing in the Southland Conference.

Notes

- "Arkansas/Arkansaw: A State and its Reputation". Old State House Museum. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- Bolton, S. Charles (Spring 1999). "Slavery and the Defining of Arkansas". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 58: 1. doi:10.2307/40026271. JSTOR 40026271.

- Blevins 2009, pp. 14–15.

- Blevins 2009, p. 16.

- "Traditions in Southern Humor". American Quarterly. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 5 (2): 113. Summer 1953.

- Blevins 2009, p. 30.

- "The Arkansas Traveler". Bentonville, Arkansas: Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- Bolton, S. Charles (Spring 1999). "Slavery and the Defining of Arkansas". The Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Arkansas Historical Association. 58: 23.

- Royko, Mike (October 11, 1992). "Opinion". Chicago Tribune.

- Blumenfield, Robert (December 1, 2002). Accents: A Manual for Actors. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 144. ISBN 978-0879109677.

- Lippi-Green 1997, p. 212.

- Lippi-Green 1997, pp. 209–210.

- Lippi-Green 1997, pp. 215–216.

- Collins, Jeffery; Wyatt, Kristen (November 24, 2011). "Hey, y'all, want to lose the drawl?". USA Today. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- "McDonough" (1975), pp. 2-3.

- "Slaw" (2012), p. 27.

- "Slaw" (2012), pp. 28-29.

- "Slaw" (2012), pp. 30.

- "McDonough" (1975), p. 67.

- "McDonough" (1975), pp. 67-68.

- Wells, Lindsey (May 27, 2018). "Nationally-recognized barbecue restaurant celebrates 90 years". Hot Springs Sentinel-Record. Hot Springs, Arkansas. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- Van Zandt, Emily (June 5, 2014). "Still Hot on Tamales". Arkansas Life. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- Sider, Alison (November 2, 2016). "Don't Tell Texas, But Arkansas Is Laying Claim to Queso". The Wall Street Journal (Central ed.). New York, NY: Dow Jones & Co. ISSN 1092-0935. OCLC 36098632. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- Rudner, Jordan (December 7, 2016). "Cheesed Off: Texas queso loses to Arkansas cheese dip in Senate competition". The Dallas Morning News. Dallas, Texas: A. H. Belo Corporation. OCLC 25174115.

- "McDonough" (1975), pp. 67-68.

- "McDonough" (1975), p. 160.

- "McDonough" (1975), pp. 167-168.

- Alexander, Amber. "Water from a Tree – Making Maple Syrup in the Ozarks". Edible Ozarkansas. Fayetteville, Arkansas: Feed Communities, Inc. (6): 14–20.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Parker, Tina (August 23, 2012). "Eureka arts programs awarded $29K in grants". Carroll County News. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- "Arkansas Arts Center presents 55th annual Delta Exhibition". Stuttgart Daily Leader. Gatehouse Media, Inc. January 21, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- Hall, Christopher (August 22, 2010). "North Little Rock Finds its Cool". Travel. The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- "McDonough" (1975), p. 186.

- Bartels, Chuck (November 12, 2012). "600K visitors later, Crystal Bridges turns 1". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- Reynolds, Chris (October 14, 2012). "Crystal Bridges art museum is reshaping Wal-Mart's hometown". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- Griffee, Carol. "Odyssey Of Survival, A History of the Arkansas Conservation Sales Tax" (PDF). p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 17, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2012.

- "Arkansas matchup is not likely soon". Sun Herald. July 20, 2003. p. 9B.

References

- Blevins, Brooks (2009), Arkansas/Arkansaw, How Bear Hunters, Hillbillies & Good Ol' Boys Defined a State, Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press, ISBN 978-1-55728-952-0

- McDonough, Nancy (1975), Garden Sass: A Catalog of Arkansas Folkways, New York, NY: Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, ISBN 9780698106406, LCCN 74-16633

- Lippi-Green, Rosina (May 25, 1997), "Hillbillies, rednecks, and southern belles", English with an Accent: Language, Ideology and Discrimination in the United States, London, England: Routledge, ISBN 978-0415114776

- Veteto, James R.; Maclin, Edward M., eds. (January 30, 2012), The Slaw and the Slow Cooked, Nashville, Tennessee: Vanderbilt University Press, ISBN 9780826518019

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culture of Arkansas. |