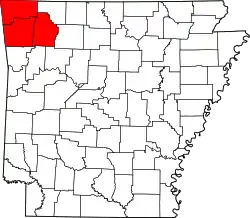

Northwest Arkansas

Northwest Arkansas (NWA) is a metropolitan area and region in Arkansas within the Ozark Mountains. It includes four of the ten largest cities in the state: Fayetteville, Springdale, Rogers, and Bentonville, the surrounding towns of Benton and Washington counties, and adjacent rural Madison County, Arkansas. The United States Census Bureau-defined Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers Metropolitan Statistical Area includes 2,674 square miles (6,930 km2) and 525,032 residents (as of 2016),[2] ranking NWA as the 105th most-populous metropolitan statistical area in the U.S. and the 22nd fastest growing in the United States.

Northwest Arkansas | |

|---|---|

| Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers MSA | |

.jpg.webp)     Clockwise from top: Fayetteville within the Ozark Mountains, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, downtown Rogers, downtown Springdale, Donald W. Reynolds Razorback Stadium | |

Northwest Arkansas | |

Northwest Arkansas Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 36°4′35″N 94°9′39″W | |

| Country | |

| States | |

| Largest cities | Fayetteville Springdale Rogers Bentonville |

| Other Municipalities | Bella Vista Siloam Springs |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3,213.01 sq mi (8,321.7 km2) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Total | 525,032 [1] (105th) |

| • Density | 153/sq mi (59/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central Time Zone (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Area code(s) | 479 |

| Website | www |

| Highest elevation 2515 ft/767 m Lowest elevation 800 ft/244 m (sea level) at Beaver Lake. | |

| Part of a series on |

| Regions of Arkansas |

|---|

|

Northwest Arkansas doubled in population between 1990 and 2010. Growth has been driven by the three Fortune 500 companies based in NWA: Walmart, Tyson Foods, and J.B. Hunt Transport Services, Inc., as well as over 1,300 suppliers and vendors drawn to the region by these large businesses and NWA's business climate. The region has also seen significant investment in amenities, including the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, the Walmart AMP, and the NWA Razorback Regional Greenway.

Etymology

The term "Northwest Arkansas" is commonly used to refer to the rapidly growing cities of Benton and Washington counties in the geographic corner of the state. Northwest Arkansas, often abbreviated NWA, has become known as a cohesive region due to the efforts of the Northwest Arkansas Council, an association of community and business leaders formally organized in 1990 to promote regionalization and cooperation among area stakeholders. The first two chairs of the NWA Council were Alice Walton and John Paul Hammerschmidt. The first major initiative using the region's name was the Northwest Arkansas National Airport (often referred to by its IATA airport code, XNA), which opened in 1998.[4] Other regional priorities advocated for by the NWA Council include Interstate 49 (initially built at I-540), the Northwest Arkansas Community College (NWACC), the Northwest Arkansas Naturals minor-league baseball team, and the Northwest Arkansas Razorback Regional Greenway 36 miles (58 km) hard-surface trail.

The region is also sometimes known as "the 479" after the telephone area code that serves the region, though the Fort Smith metro also uses the 479 area code.[5] Occasionally, the Fort Smith metro is included in "Northwest Arkansas", though it is within the geographically distinct Arkansas River Valley region and separated from the subject region by the sparsely populated Boston Mountains.

Geography

Northwest Arkansas is located in the Southern United States. It is within the Upper South, characterized by the Ozarks. The southern part of NWA is a high and deeply dissected plateau, full of sparsely populated oak-hickory forest, separating the region from the Arkansas River Valley to the south.

Political geography

Settlements were initially founded in the 19th century and early 20th century as individual communities, with Fayetteville, Springdale, Rogers, and Bentonville serving as historic population centers in the area. Growth began during the mid-20th century, a period of suburbanization largely rooted in automobile dependency. Thus the Northwest Arkansas cities expanded toward one another along major transportation corridors, in some cases becoming seamlessly connected urban areas such as Prairie Grove and Farmington along US 62 now connected to Fayetteville's southwest side.[6] The transition from individual communities separated by rural or agricultural lands accelerated rapidly in the 1990s and early 2000s, as the population of the region doubled.[4] Cities began rapidly annexing unincorporated lands, especially near the four-largest focal cities, adding an additional 45.5 square miles (118 km2) or 16% of incorporated size between 2000 and 2004.[7] The Northwest Arkansas Regional Planning Commission (NWARPC, the region's metropolitan planning organization) expanded its planning area to include all of Benton and Washington counties in 2003.[8] Annexations along transportation corridors spurred the need for expanding roadways, including along US 62 southwest of Fayetteville and northeast of Rogers, and Highway 59 north from Siloam Springs.[8]

The United States Census Bureau definition includes Benton, Washington, and Madison counties in Arkansas. Until 2018, the Census Bureau also included McDonald County, Missouri.

Cities

.jpg.webp)

Fayetteville is the county seat of Washington County and home to the University of Arkansas. As of the 2010 census, the city had a total population of 76,899.[9] The city is the third most populous in Arkansas and serves as the county seat of Washington County. It's also known for Dickson Street, perhaps the most prominent entertainment district in the state of Arkansas, which itself contains the Walton Arts Center. Blocks from Dickson Street is the Fayetteville Historic Square, which hosts the nation's number one ranked Fayetteville's Farmer's Market.[10] Fayetteville was also ranked 8th on Forbes Magazine's Top 10 Best Places in America for Business and Careers in 2007.[11] Business insider named Fayetteville the 2nd best place to live in the South in 2016.

Springdale is a city in Washington and Benton Counties. According to the 2010 census, the population of the city is 73,123. Springdale is currently Arkansas's fourth-largest city, behind Little Rock, Fort Smith, and Fayetteville. Springdale is the location of the headquarters of Tyson Foods Inc., the largest meat producing company in the world, and has been dubbed the "Chicken Capital of the World" by several publications. In 2008, the Wichita Wranglers of AA minor league baseball's Texas League moved to Springdale and play in Arvest Ballpark as the Northwest Arkansas Naturals.

Rogers is a city in Benton County. As of the 2010 census, the city is the eighth most populous in the state, with a total population of 58,895. Rogers is famous as the location of the first Wal-Mart. In June 2007, BusinessWeek magazine ranked Rogers 18th in the 25 best affordable suburbs in the South. In 2010, CNN Money magazine ranked Rogers as the 10th Best Place to Live in the United States. Two of the city's biggest attractions are the outdoor concert venue the Walmart AMP and the open air shopping mall the Pinnacle Hills Promenade. The city is the home town of American country music singer/songwriter Joe Nichols, and Marty Perry, as well as David Noland. It is also where comedian Will Rogers married Betty Blake.

Bentonville is the county seat of Benton County. At the 2010 census, the population was 38,284, up from 20,308 in 2000 ranking it as the state's 10th largest city. It is home to the headquarters of Walmart, which is the largest retailer in the world, and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Crystal Bridges, founded by Sam Walton's daughter Alice Walton and designed by world-renowned architect Moshe Safdie, is home to some of America's finest works of art as well as Frank Lloyd Wright's Bachman-Wilson House.[12] Southern Living magazine recently cited Bentonville as "the South's next cultural mecca."[13]

Cityscapes

Bentonville

Bentonville Downtown Fayetteville

Downtown Fayetteville University of Arkansas Campus, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas Campus, Fayetteville Rogers

Rogers Emma Avenue, Springdale

Emma Avenue, Springdale Arvest Ballpark, Springdale

Arvest Ballpark, Springdale Sager Creek, Siloam Springs

Sager Creek, Siloam Springs

Geology

NWA is located within the Ozark Mountains, a deeply dissected plateau within the U.S. Interior Highlands, the largest mountainous region between the Appalachians and the Rocky Mountains. Although the topography varies widely within the region, the Ozark geology is present throughout. Roughly at Fayetteville, the geology splits between the Boston Mountains to the south and the Springfield Plateau to the north. The Ouachita orogeny exposed the older limestones of the Springfield Plateau, resulting in a softer terrain, while the Boston Mountains retained steep, sharp grade changes. The Ozarks are covered by an oak-hickory-pine forest, with large portions of protected forestland remaining NWA. Approximately 25% of this forest has been cleared for development and agricultural uses.[14]

Hydrology

Most of NWA is within the White River watershed, with the western portions being contained within the Illinois River watershed.

Within NWA, the White River is impounded at several locations, the most important of which is at Beaver Dam, forming the 13,700 acres (5,500 ha) Beaver Lake. This reservoir was created in the 1960s for flood control, recreational, and energy production uses. It also serves as the water supply for most of NWA, with Beaver Water District treating potable water and selling it directly to the four largest NWA municipalities.

The Illinois River watershed is a sensitive watershed that has been the subject of controversy within the area for many years. The phosphorus load of the Illinois has been subject of controversy, eventually resulting in litigation between Oklahoma and Arkansas reaching the United States Supreme Court in 1992. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has classified the Illinois as Section 303(d) of the Clean Water Act, listing it as an "impaired and threatened water" due to the high phosphorus loads.[15]

Parks

The Northwest Arkansas region is known for its natural environment, and outdoor recreation. When selecting a name for the new minor league baseball team in the early 2000s, Northwest Arkansas Naturals was selected in honor of the region's natural resources, including a waterfall in the initial logo to symbolize the region's over 130 naturally occurring waterfalls.[16] The region offers thousands of acres of public land under various agencies, ecoregion type, and function. Despite rapid suburbanization, over half of Washington and 40% of Benton county remained forested in 2015.[17] The region has maintained an open space plan since 2015, and has considered a sales tax to fund purchases of open lands by the Northwest Arkansas Land Trust.[18]

An expansive trail network has been built across Northwest Arkansas, centered on the Northwest Arkansas Razorback Regional Greenway, a 38-mile (61 km) primarily off-road shared-use paved trail connecting the region's major cities, employer headquarters, schools, parks and cultural amenities. Upon completion in 2015, the Greenway connected to 68 miles (109 km) of other hard-surfaced trails and over 100 miles (160 km) of soft-surface nature trails throughout the region.[19] Northwest Arkansas has drawn endorsement from the mountain biking community, earning a 'Regional Ride Center' designation from the International Mountain Bicycling Association in 2015, the first granted to a region rather than a city.[20] Mountain biking trail development has continued, adding mileage in the state parks along natural features.[21]

The most popular water destination is Beaver Lake. Beaver Lake has approximately 449 miles (723 km) of natural shoreline, with limestone bluffs, natural caves, and a variety of trees and flowering shrubs. Paved access roads wind through twelve developed parks, all of which have campsites offering electricity, fire rings, drinking water, showers, and restrooms. Other facilities, such as picnic sites, swimming beaches, hiking trails, boat launch ramps, and sanitary dump stations are also available.[22] Nine rivers can be canoed, paddled, or floated seasonally when stream flows permit, including the nearby Buffalo National River and nearby Illinois River, King's River, and Elk River.[23]

The University of Arkansas offers equipment rental and outdoor excursions into the Ozarks for students.[24]

The Botanical Garden of the Ozarks opened in 2007, and includes seasonal plantings in a small area, a wildflower meadow, a lakeside hiking trail, and a self-guided tree identification tour.

State parks and areas

The region contains three state parks. Hobbs State Park - Conservation Area, the largest state park in Arkansas, is jointly managed by the Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, and the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission.[25] Devil's Den State Park is a popular hiking and camping destination near Winslow. Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park preserves the history of the Civil War Battle of Prairie Grove.

The three-county region also contains two natural areas, Garrett Hollow Natural Area, Sweden Creek Natural Area, and four wildlife management areas (Beaver Lake WMA, McIlroy Madison County WMA, Wedington WMA, White Rock WMA).

Culture and contemporary life

Art and entertainment

The Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville opened in 2011.[26] The museum, funded by Sam Walton's daughter, Alice Walton, and designed by world-renowned architect Moshe Safdie, is home to a permanent collection of works, as well as rotating exhibits throughout the year. The Walton Arts Center is Arkansas' largest performing arts center. It is located in Fayetteville near the campus of the University of Arkansas and serves as a cultural center for the Northwest Arkansas area. The theater was opened in 1992 and was funded largely by the Walton family (of Wal-Mart). The center is host to many musicals, plays, and other artistic and educational events throughout the year. The Walton Arts Center is also home to the Symphony of Northwest Arkansas, currently under the direction of Paul Haas.[27]

TheatreSquared is Northwest Arkansas's regional professional theatre. Its four-play season and annual Arkansas New Play Fest are attended by an audience of 22,000, including educational outreach program to approximately 10,000 students and their teachers. The company was recognized by the American Theatre Wing in 2011 as one of the nation's ten most promising emerging theatres.

The Arts Center of the Ozarks is the region's oldest community theatre. Since its inception in 1967, the ACO has grown from a small arts organization into a cultural center of regional significance. Located in downtown Springdale, the ACO offers a full season of mainstage plays and musicals, children's programs, visual arts exhibits, and classes in a variety of creative outlets.

The Bentonville square features the Wal-Mart Visitors Center. Located in Sam Walton's original Bentonville variety store, the Wal-Mart Visitors Center traces the origin and growth of Wal-Mart. The center was created as an educational and informative facility as well as a museum.

Dickson Street and the surrounding area in downtown Fayetteville is the main entertainment district of the region, located just off the University of Arkansas campus. The area is dense with restaurants, bars, and shops. Dickson Street is home to the Walton Arts Center, the Bikes, Blues, and BBQ Festival, and many parades.

Festivals

- Bikes, Blues, & BBQ motorcycle rally on Dickson Street in Fayetteville with over 400,000 people attending over four days[28]

- Since 2015, the Bentonville Film Festival has taken place in the first week of May. Over 85,000 attendees take part in this week-long event.[29]

- Since 1974, the Dogwood Festival has brought around 30,000 people to Siloam Springs and its parks for a 3-day event. Food, crafts, entertainment, flea market items, and KidZone activities make for a fun day for all ages. Held the weekend of the last Sunday in April each year.[30]

- In 2009, the City of Fayetteville began assisting in the sponsorship of All Out June, Northwest Arkansas' pride festival for the LGBT community. The event is considered Arkansas' largest, and is organized by the NWA Center for Equality and the NWA Pride Parade Organization.

- Walmart Shareholder's Meeting at Bud Walton Arena brings over 5,000 employees to Fayetteville from around the world.[31]

- Since 2011, the World Championship Squirrel Cook Off in Bentonville[32]

- Battle of Prairie Grove Reenactment, hundreds of Civil War reenactors camp and fight at Prairie Grove Battlefield State Park in December of even-numbered years[35]

Sports

.jpg.webp)

The sporting scene is large in Northwest Arkansas, primarily due to the presence of the University of Arkansas Razorbacks, Arkansas’ most successful, followed, and loved sports teams. The Razorbacks have a huge economic impact on the area, drawing fans from every corner of the state during football, basketball, and baseball seasons.

The Razorbacks currently field 19 total men's and women's varsity teams (8 men's and 11 women's) in 13 sports. The men's varsity teams are baseball, basketball, cross country, football, golf, tennis, and indoor and outdoor track and field; the 11 women's varsity teams are basketball, cross country, golf, gymnastics, soccer, swimming and diving, indoor and outdoor track, tennis, softball and volleyball. The Razorbacks compete in NCAA Division I (Division I FBS in football) and are currently members of the Southeastern Conference (Western Division).

Facilities include: Reynolds Razorback Stadium, Bud Walton Arena, Baum Stadium, Randal Tyson Indoor Track Center, and the John McDonnell Field.

In early 2008, Northwest Arkansas welcomed a Double-A minor league baseball team, formerly known as the Wichita Wranglers, to Springdale, where they became the Northwest Arkansas Naturals. The Naturals play at the newly completed Arvest Ballpark.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 12,151 | — | |

| 1850 | 18,503 | 52.3% | |

| 1860 | 31,719 | 71.4% | |

| 1870 | 39,328 | 24.0% | |

| 1880 | 55,627 | 41.4% | |

| 1890 | 77,142 | 38.7% | |

| 1900 | 85,731 | 11.1% | |

| 1910 | 83,334 | −2.8% | |

| 1920 | 86,639 | 4.0% | |

| 1930 | 87,842 | 1.4% | |

| 1940 | 91,793 | 4.5% | |

| 1950 | 99,789 | 8.7% | |

| 1960 | 101,137 | 1.4% | |

| 1970 | 137,299 | 35.8% | |

| 1980 | 189,982 | 38.4% | |

| 1990 | 222,526 | 17.1% | |

| 2000 | 325,364 | 46.2% | |

| 2010 | 440,121 | 35.3% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 534,904 | [36] | 21.5% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[37] 1790–1960[38] 1900–1990[39] 1990–2000[40] 2010–2016[41] | |||

| Region compared to State & U.S. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 Census[42][43] | NWA | Arkansas | U.S. |

| Total population | 463,204 | 2,915,918 | 308,745,538 |

| Population change, 2000 to 2010 | +33.5% | +9.1% | +9.7% |

| Population density (people/sqmi) | 144.2 | 54.8 | 87.4 |

| Median household income (2016)[44] | $51,848 | $44,334 | $57,617 |

| Bachelor's degree or higher[45] | 28.2% | 19.5% | 25.1% |

| Foreign born (2016) | 10.7% | 4.7% | 13.7% |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 81.9% | 77.0% | 72.4% |

| Black | 1.9% | 15.3% | 12.6% |

| Hispanic (any race) | 14.9% | 6.4% | 16.3% |

| Asian | 2.3% | 1.2% | 4.8% |

Northwest Arkansas is the second-largest population center in the state, behind Central Arkansas. The two regions rank as 104th and 78th nationally by population, respectively. The region is the fastest-growing in the state, and the 15th fastest-growing in the United States, with a 16.03% growth rate between 2010 and 2017.[46] Rather than a central city with suburbs model, Northwest Arkansas emerged as a unified region as small, disconnected cities grew and amalgamated over time. Thus, the official Census Bureau name Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers Metropolitan Statistical Area does not reflect traditional "Fayetteville as a principal city, with Springdale and Rogers as suburbs" model; rather a listing of the three largest cities in the region at the time of naming.[47]

Over half of Northwest Arkansas's population resides within the largest four cities, Fayetteville, Springdale, Rogers, and Bentonville, with each having demographic characteristics congruent with its largest employer. Fayetteville, home to the University of Arkansas, contains the highest proportion of adults over 25 with a bachelor's degree or higher, at 44.8%, significantly above the other communities, and in line with major metropolitan areas. Bentonville, home to white-collar workers at the Walmart Home Office and the ancillary vendor community, has the highest per-capita income in the region.[47] Springdale and Rogers contain significant manufacturing and construction industries, and a corresponding high percentage of Blue-collar workers and major foreign-born populations.[48] Over 10% of businesses in Springdale and Rogers are Hispanic-owned.[47]

Approximately half of Northwest Arkansas residents are transplants from a different state or country.

| County Ref. |

Population | Land mi² |

Land km² |

Pop. /mi² |

Pop. /km² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benton County[49] | 258,291 | 847.36 | 2,194.65 | 261.2 | 100.85 |

| Washington County[50] | 228,049 | 941.97 | 2,439.69 | 215.6 | 83.24 |

| Madison County[51] | 16,072 | 834.26 | 2,160.72 | 18.8 | 7.26 |

| Northwest Arkansas | 525,032 | 3,163.07 | 8,192.31 | 166.0 | 64.09 |

| Arkansas | 2,988,248 | 52,035.48 | 134,771.27 | 56.0 | 21.62 |

Race and ethnicity

The region is less diverse than Arkansas and United States averages, with a 1.9% black population accounting for much of the proportional difference. The national trends of an increasing non-white proportion of the population and migration from rural areas to urban areas has also been seen in Northwest Arkansas and statewide since the 1990s, though the non-white population growth has lagged national averages.[52] Historically, the northwestern half of the state was predominantly settled by whites in small farms for subsistence agriculture due to the hilly terrain and rocky soils, rather than the slave-intensive labor of plantation agriculture typical in the fertile and flat Arkansas Delta.[53]

Northwest Arkansas institutions have placed different priority on diversity within the region. University of Arkansas Chancellor John A. White designated diversity the top institutional goal in 2010, seeking to create a campus community in line with state and national averages.[54] The Northwest Arkansas Council listed "Promote racial, cultural, and ethnic diversity in Northwest Arkansas" last among priority placemaking objectives within the 2015 strategic plan.[55]

The city of Gentry has a dense community of Hmong Americans, many resettled by the United States after the North Vietnamese invasion of Laos and subsequent Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act.[56] Hmong National Development, a subsidiary of Hmong American Partnership, has an office in Fayetteville and Fairview, Missouri, one county north of the official Northwest Arkansas boundary. Gentry School District was the epicenter of cultural conflicts among Hmong, Hispanic, and white residents in the early 2000s.[57]

A 2016 study of blacks and Hispanics in Arkansas cities found median incomes rising for blacks and declining for Hispanics in Bentonville.[58]

Sexual orientation and gender identity

The Northwest Arkansas Center for Equality has sponsored the Northwest Arkansas Pride parade since 2006. The parade runs from the Fayetteville Historic Square down Dickson Street in Fayetteville.[59] A state poll in 2017 showed 84% of Arkansans believe LGBT residents should have equal employment rights, and 78% believing equal rights to housing should be afforded. Arkansan support for equal treatment in adoptions (43%), and gay marriage (35%), were significantly below national averages, 61% and 64%, respectively.[60] Arkansas is one of three states which does not prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity.[61] Fayetteville and Eureka Springs have recently worked to provide legal protections for LGBT residents. Fayetteville has worked legislatively and through the court system since 2014 to establish protections for LGBT residents in the city.

The Fayetteville City Council passed Ordinance 119 in August 2014 by a 6-2 vote at 3:20 am, after an extended public comment period, which included testimony from LGBT residents who had encountered discrimination.[62] Ordinance 119 extended protections, including against termination and eviction, and created a Civil Rights Commission to investigate violations. An opposition group gathered enough signatures to put repealing the ordinance to the voters of Fayetteville, who repealed the ordinance by a 52-48% margin.[63] The City Council put a similar measure, the Uniform Civil Rights Protection Ordinance 5781, to a public vote in September 2015, which passed 53-47%.[64] In the interim, Republican State Senator Bart Hester, who represents northwestern Benton County in Northwest Arkansas, proposed the Intrastate Commerce Improvement Act in response to the Fayetteville Ordinance, which prohibited municipalities in Arkansas from creating new protected classes in Arkansas.[65] The Arkansas General Assembly passed the act, known as Act 137.[66] In February 2017, the Arkansas Supreme Court declared Ordinance 5781 unconstitutional for violating Act 137, but did not rule on the act's constitutionality, which has been questioned.[64] The ruling drew national attention to Arkansas, and comparisons to HB 2 in North Carolina.[61]

Northwest Arkansas' All Out June, a pride festival for its LGBT community, is considered Arkansas' largest, and is organized by the NWA Center for Equality and the NWA Pride Parade Organization.

2000

As of the census[67] of 2000, there were 347,045 people, 131,939 households, and 92,888 families residing within the MSA. The racial makeup of the MSA was 89.70% White, 1.22% African American, 1.53% Native American, 1.19% Asian, 0.29% Pacific Islander, 4.03% from other races, and 2.04% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.32% of the population. Over the past decade or more, Northwest Arkansas has been one of the fastest growing regions in the South.

The median income for a household in the MSA was $32,469, and the median income for a family was $38,118. Males had a median income of $27,025 versus $20,295 for females. The per capita income for the MSA was $16,159.

Economy

Booming prosperity accompanying a tremendous increase in the area's population has made Northwest Arkansas a recognized economic success. Many migrants come from Northeast Arkansas, South-Central Arkansas, and North Central Arkansas, to work in this booming area. The area is now seeking residents from places like Southwest Arkansas, and even Southeast Arkansas. The state's population grew 13.7 percent between 1990 and 2000, but the two-county metropolitan statistical area accounted for one-third of that growth. Benton and Washington counties grew 47 percent between 1990 and 2000. Almost all of the people who moved to those counties then were from California, Oklahoma, Missouri, Kansas, Texas and other parts of Arkansas.[68] Estimates put the two-county population at roughly 373,055 by December 2004. Even during national economic turmoil, Northwest Arkansas has experienced 8.2 percent job growth. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in February 2008 the Northwest Arkansas region as a whole had an unemployment rate of 4.1%.[69] This unemployment rate gave Northwest Arkansas a rank of 41 out of 369 metropolitan areas in the United States. Per capita income in Northwest Arkansas is $31,191, according to the most recent figures from the United States Census Bureau.[70] This is approximately $7,000 below the average per capita income.[70]

Bentonville is world-renowned as a retail capital of the world, as it is headquarters to Wal-Mart Stores Incorporated. Springdale is home to Fortune 75 company Tyson Foods, the world's leading producer of poultry and beef, and second-largest producer of pork. J.B. Hunt Transport Services in Lowell, is the nation's largest publicly owned truckload carrier, with international networks in Canada and Mexico.

The region has been noted for income inequality, as rapid growth and inflow of professionals have come to a historically poor region in a poor state. Multinational companies have struggled to find a local workforce with the education, skills, and talent large enough to fuel the growing headcounts. The result has been a large number of transplants moving to the area from larger metropolitan areas in pursuit of jobs and amenities at a lower cost of living.[71] Wealthy enclaves such as Pinnacle in Rogers and amenities built to cater to transplants to the area have transformed the economies and cultures of Northwest Arkansas's formerly small, quiet towns.[72]

Human resources

Education

Northwest Arkansas has a strong tradition of education. Cane Hill College was founded in western Washington County in 1834; the first college in Arkansas, and Arkansas College was founded in Fayetteville in 1850.[lower-alpha 1] Though both colleges are now defunct, these institutions laid the groundwork for establishing the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville in 1871, today the largest and best-known university in the state. Seven of the top ten school districts in Arkansas are within Benton or Washington counties, including Haas Hall Academy, a top 100 high school nationwide.[73]

As of July 2016, 85.3% of Northwest Arkansas residents over age 25 held a high school degree or higher and 30.9% holding a bachelor's degree or higher. The Northwest Arkansas rates are above Arkansas averages of 84.8% and 21.1%, and near national averages of 86.7% and 29.8%, respectively.[lower-alpha 2]

Primary and secondary education

Northwest Arkansas public school districts range from small, rural districts to some of the largest districts in the state. Among the four large cities, each district contains two high schools, with the exception of Fayetteville Public Schools: Bentonville and Bentonville West, Rogers and Rogers Heritage, and Springdale and Springdale Har-Ber. These schools, combined with Fayetteville (and Van Buren from the Arkansas River Valley) constitute the 7A West Conference for athletics, the largest class in the state. The region's growth has led to many new schools throughout the region, including high schools. Rogers Heritage High School was established in 2008, Rogers New Technology High School, and Bentonville West High School opened in 2014.

There are also several private, charter, parochial, and secular schools, including Shiloh Christian School in Springdale.

Higher education

- University of Arkansas

- The University of Arkansas (UA) is a public co-educational land-grant university. It is the flagship campus of the University of Arkansas System and is located in Fayetteville, Arkansas. It is noted for its strong architecture, agriculture (particularly poultry science), creative writing, and business programs. Sports are also important to the university, as they are home to the Arkansas Razorbacks.[75]

- John Brown University

- Northwest Arkansas Community College (NWACC)

- Ecclesia College

Public library systems

The Fayetteville Public Library is the largest library in Northwest Arkansas. The other libraries in Washington County have formed the Washington County Library System (WCLS).

Infrastructure

Surface transportation

The region is mainly served by Interstate 49. I-49 has been the cause of much frustration in the area due to frequent traffic jams and accidents caused by the sudden growth of the area. In addition, cities' infrastructure investments did not keep pace with the population growth so streets are frequently congested. A widening of I-49 to six lanes and improvements to interchanges, including Arkansas's first single-point urban interchange at Exit 85 , are currently in the final stages . Other major highways that serve the area include US 62, US 71, US 71B, and US 412.

Aviation

Northwest Arkansas National Airport (often referred to by its IATA airport code, XNA) is the primary commercial service airport in the region. The facility opened in 1998, supplanting Drake Field in Greenland, which remains as a general aviation facility. XNA has one concourse, with twelve gates. The three most popular destinations for the year-long period ending June 2017 were Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, and O'Hare International Airport, hubs for American Airlines, Delta Airlines, and United Airlines, respectively.[76] The Northwest Arkansas Council has prioritized attracting a low-cost carrier to the airport, and has had relative success with Allegiant Air, which offers three permanent and three seasonal destinations.

The region has seven smaller, public use general aviation airports, including Drake Field, Rogers Executive Airport, Springdale Municipal Airport, Bentonville Municipal Airport, Siloam Springs Municipal Airport, Crystal Lake Airport, and Huntsville Municipal Airport. Beaver Lake Aviation, a wholly owned subsidiary of Walmart, is based in Rogers.

Mass transit

Two public transit agencies serve the area; Ozark Regional Transit is a general transit agency with around a dozen local routes, plus commuter, paratransit, and special purpose routes. Razorback Transit primarily serves University of Arkansas students, is fare-free, and has a service area limited to Fayetteville. It is also open to the general public.

See also

- Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art

- McDonald Territory, a failed attempt by McDonald County, Missouri to leave Missouri and become part of Arkansas in 1961

- Walton Arts Center

- Arkansas metropolitan areas

Notes

- Not the same institution as Lyon College, also founded as Arkansas College but in Batesville in 1872.

- Calculated using the percentages and overall populations to total for the four-county area.[74]

References

- "Northwest Arkansas clocks in at No. 22 for fast-growing U.S. metro areas". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. 2017-03-23. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- "Northwest Arkansas clocks in at No. 22 for fast-growing U.S. metro areas". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. 2017-03-23. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Della Rosa, Jeff (November 18, 2018). "XNA marks 20 years in business, connects region to the world". Talk Business & Politics. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Bowden, Bill (August 11, 2010). "Paving the way for 20 years". Arkansas Democrat Gazette. Little Rock. p. 7. Retrieved July 5, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- "Area Codes Map AR - Arkansas". North American Numbering Plan. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- Bernet, Brenda (March 28, 2012). "Report shows urban area numbers rise - Northwest Arkansas ranks 15th for growth from '00-'10". Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock: WEHCO Media. p. 9. Retrieved July 5, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Smith, Robert J. (June 28, 2004). "NW Arkansas is leading state in annexations - Cities looking to grow want voters to decide fate of local boundaries". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, AR. p. 8. Retrieved July 5, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Branan, Brad (January 18, 2003). "Transportation boundary widens - Regional planners expand their reach amid counties' rapid growth". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock. p. 21. Retrieved July 5, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- "U.S. Census Bureau Delivers Arkansas' 2010 Census Population Totals, Including First Look at Race and Hispanic Origin Data for Legislative Redistricting". United States Census Bureau. February 10, 2011. Archived from the original (URL) on May 23, 2012. Retrieved 2011-09-14.

- "America's Current Favorite Farmer's Markets ™: Top 20 Large". American Farmland Trust. Archived from the original on 2011-09-04. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- "Best Places For Business And Careers, #8 Fayetteville, AR". Forbes, Inc. 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2011-09-14.

- Ashley, Amanda. "Frank Lloyd Wright House dismantled, headed for new home at Crystal Bridges". nwahomepage.com. NWA. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- "Is Bentonville The South's Next Cultural Mecca?". Southern Living. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- "Primary Distinguishing Characteristics of Level III Ecoregions of the Continental United States". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. April 2000. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- "Illinois River Watershed". Environmental Protection Agency. May 22, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- Wood, Terry J. (May 30, 2007). "It's a Natural - New Royals affiliate taps into region's resources for logo design". Northwest Arkansas Times. Fayetteville. p. 8. Retrieved July 11, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Sims, Scarlet (January 1, 2015). "'A Matter of Choices' - Region Plans to Maintain Forests as Urban Sprawl Beckons". Springdale Morning News. Springdale. p. 1A. Retrieved July 11, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Wood, Ron (October 14, 2019). "Coalition works to preserve open space in NW Arkansas". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, AR: WEHCO Media. pp. 8, 13. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- Moss, Teresa (December 27, 2014). "Greenway reaching finish line - Last stretch of trail system 'spine' to be built in spring". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock: WEHCO Media. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- Gute, Melissa (August 16, 2015). "Recognition of trails expected to increase Arkansas tourism". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock: WEHCO Media. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- Murphy, Jocelyn (June 13, 2019). "Touring The Trails". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock: WEHCO Media. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- "July - Be lazy at Beaver Lake". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock: WEHCO Media. October 6, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- Putthoff, Flip (March 29, 2015). "Recreation abounds on region's public lands, water - About nine nearby waterways can be floated including the Buffalo River". Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock: WEHCO Media. p. 137. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- Andrews, Avital (August 14, 2012). "Outside University: The Top 25 Colleges for Outside Readers". Outside. Outside Integrated Media, LLC. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- Blad, Evie (July 21, 2007). "'A rare jewel' Leaders turn dirt to start construction of a visitors center at Hobbs State Park". Benton County Daily Record. p. 1. Retrieved August 30, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- http://www.nwanews.com/adg/News/205722/%5B%5D

- 3W Magazine, , Symphony of Northwest Arkansas Announces Paul Haas as Music Director August 25, 2010

- Martin-Brown, Becca (September 22, 2019). "More, More, More! Now 20, Bikes, Blues & BBQ revs its engines". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, AR: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc.

- "BFF Announces Continued Growth & 2019 Dates! - Bentonville Film Festival". bentonvillefilmfestival.com. 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- Annual Dogwood Festival – Siloam Springs, Arkansas

- Belkin, Douglas (June 5, 2017). "Wal-Mart CEO Touts Tech, Tells Shareholders Momentum is 'Real'". The Wall Street Journal. New York, NY: Dow Jones & Company. OCLC 36098632. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Putthoff, Flip (October 1, 2019). "Crowd goes nuts over World Championship Squirrel Cook Off". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock: WEHCO Media. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- Hightower, Lara (August 18, 2019). "It Takes A Village: Volunteers are key to keeping Roots Fest sustainable". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, AR: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Murphy, Jocelyn (August 18, 2019). "Roots Returns: Music, food fest celebrates 10 years". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, AR: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. Retrieved January 11, 2020.

- Staff of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette (December 2, 2016). "FYI". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Little Rock, AR: Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, Inc. Retrieved January 11, 2020 – via NewsBank.

- "County Population Totals and Components of Change: 2010-2018". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 2, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2013.

- QuickFacts for New Yory City / New York State / United States, United States Census Bureau. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- New York City Population Projections by Age/Sex & Borough, 2010–2040, New York City Department of City Planning, December 2013. Accessed February 9, 2017.

- "Selected Population Profile In The United States". American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. United States Census Bureau. 2016. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- "Educational Attainment, United States, Arkansas, Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers, AR-MO Metro Area". American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. United States Census Bureau. 2016. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017". 2016 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 2016. Archived from the original (CSV) on February 13, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- Gascon, Charles S.; Varley, Michael A. (January 2015). "Metro Profile: A Tale of Four Cities: Widespread Growth in Northwest Arkansas". The Regional Economist. St. Louis, Missouri: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Monroe, Jill (1999). Hispanic Immigration in Arkansas (PDF) (Honors Undergraduate thesis). Arkadelphia, Arkansas: Henderson State University. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- U.S. Census Bureau (July 1, 2016), Benton County QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts, retrieved December 17, 2017

- U.S. Census Bureau (July 1, 2016), Washington County QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts, retrieved December 17, 2017

- U.S. Census Bureau (July 1, 2016), Madison County QuickFacts from the US Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau: State and County QuickFacts, retrieved December 17, 2017

- Hamilton, Gregory; McLendon, Terre; Wingfiel, Vaughan (February 2006). "Arkansas 2020 - Arkansas Population Projections and Demographic Characteristics for 2020" (PDF). Little Rock, Arkansas: University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Donald W. Reynolds Center for Business and Economic Development, Institute for Economic Advancement. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Graves, John William (August 16, 2017). "African Americans". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies, Central Arkansas Library System.

- Robinson II, Charles F.; Williams, Lonnie R. (February 20, 2015). Remembrances in Black: Personal Perspectives of the African American Experience at the University of Arkansas, 1940s–2000s. Fayetteville, Arkansas: University of Arkansas Press. p. 279.

- "Greater Northwest Arkansas Development Strategy" (PDF). Northwest Arkansas Council. January 27, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- "Arkansas Community Sees Changing Face of Immigration". NPR. August 20, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Krupa, John (June 19, 2006). "Culture clash reaches a boiling point in quiet town of Gentry". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- "Examining the Status of African Americans and Hispanics in Arkansas" (PDF). University of Arkansas, Sam M. Walton College of Business, Center for Business and Economic Research. 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- Lanning, Curt (June 25, 2015). "Fayetteville To Host Pride Parade". Fort Smith, Arkansas: KFSM-TV. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Parry, Janine A. "The Arkansas Poll, 2017 Summary Report" (PDF). University of Arkansas J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- "Arkansas Supreme Court strikes city's LGBT protections". Little Rock, Arkansas: CBS. February 23, 2017.

- Gill, Todd (August 20, 2014). "Fayetteville passes civil rights ordinance". Fayetteville Flyer. Wonderstate Media, LLC. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Thomas, Dillon; Sitek, Zuzanna (December 9, 2014). "Voters Repeal Fayetteville Civil Rights Ordinance". Fort Smith, Arkansas: KFSM-TV. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Ryburn, Stacy (September 22, 2017). "Judge denies state's motion to stop Fayetteville civil rights ordinance". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- "Intrastate Commerce Improvement Act (Act 137) Arkansas Passes Statute Prohibiting Local Governments from Creating New Protected Classifications". Harvard Law Review. Harvard Law School. Dec 10, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- "Act 137 of 2015" (PDF). Arkansas Code. State of Arkansas. February 24, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Forbes https://www.forbes.com/special-report/2011/migration.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Unemployment Rates for Metropolitan Areas

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-06-19. Retrieved 2008-08-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dunham, Kemba J.; Stringer, Kortney (February 10, 2005). "Wal-Mart Fosters A Region's Rise, But Not All Benefit". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Co. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- Nassauer, Sarah (March 8, 2018). "Walmart's Arkansas Hometown Is a Mecca for Luxury-Home Buyers". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Co. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- "Arkansas High Schools". Washington, D.C.: U.S. News & World Report. 2017. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- "American Community Survey". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2016. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- University Of Arkansas

- AR: Northwest Arkansas Regional&carrier=FACTS "RITA – BTS – Transtats" Check

|url=value (help). Retrieved November 11, 2017.