History of the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, which along with the United States House of Representatives—the lower chamber—comprises the legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. Like its counterpart, the Senate was established by the United States Constitution and convened for its first meeting on March 4, 1789 at Federal Hall in New York City. The history of the institution begins prior to that date, at the 1787 Constitutional Convention, in James Madison's Virginia Plan, which proposed a bicameral national legislature, and in the Connecticut Compromise, an agreement reached between delegates from small-population states and those from large-population states that in part defined the structure and representation that each state would have in the new Congress.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| United States Senate |

|---|

Great Seal of the United States Senate |

| History of the United States Senate |

| Members |

|

| Politics and procedure |

| Places |

Constitutional creation

The U.S. Senate, named after the ancient Roman Senate, was designed as a more deliberative body than the U.S. House. Edmund Randolph called for its members to be "less than the House of Commons ... to restrain, if possible, the fury of democracy." According to James Madison, "The use of the Senate is to consist in proceeding with more coolness, with more system, and with more wisdom, than the popular branch." Instead of two-year terms as in the House, senators serve six-year terms, giving them more authority to ignore mass sentiment in favor of the country's broad interests. The smaller number of members and staggered terms also give the Senate a greater sense of community.

Despite their past grievances with specific ruling British governments, many among the Founding Fathers of the United States who gathered for the Constitutional Convention had retained a great admiration for the British system of governance. Alexander Hamilton called it "the best in the world," and said he "doubted whether anything short of it would do in America." In his Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States, John Adams stated "the English Constitution is, in theory, both for the adjustment of the balance and the prevention of its vibrations, the most stupendous fabric of human invention." In general, they viewed the Senate to be an American version of House of Lords.[2] John Dickinson said the Senate should "consist of the most distinguished characters, distinguished for their rank in life and their weight of property, and bearing as strong a likeness to the British House of Lords as possible."[3] The Senate was also intended to give states with smaller populations equal standing with larger states, which are given more representation in the House.

The apportionment scheme of the Senate was controversial at the Constitutional Convention. Hamilton, who was joined in opposition to equal suffrage by Madison, said equal representation despite population differences "shocks too much the ideas of justice and every human feeling."[4] Referring to those who demanded equal representation, Madison called for the Convention "to renounce a principle which was confessedly unjust."

The delegates representing a majority of Americans might have carried the day, but at the Constitutional Convention, each state had an equal vote, and any issue could be brought up again if a state desired it. The state delegations originally voted 6–5 for proportional representation, but small states without claims of western lands reopened the issue and eventually turned the tide towards equality. On the final vote, the five states in favor of equal apportionment in the Senate—Connecticut, North Carolina, Maryland, New Jersey, and Delaware—only represented one-third of the nation's population. The four states that voted against it—Virginia, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Georgia—represented almost twice as many people than the proponents. Convention delegate James Wilson wrote "Our Constituents, had they voted as their representatives did, would have stood as 2/3 against equality, and 1/3 only in favor of it".[5] One reason the large states accepted the Connecticut Compromise was a fear that the small states would either refuse to join the Union, or, as Gunning Bedford, Jr. of Delaware threatened, "the small ones w[ould] find some foreign ally of more honor and good faith, who will take them by the hand and do them justice".[6]

In Federalist No. 62, James Madison, the "Father of the Constitution," openly admitted that the equal suffrage in the Senate was a compromise, a "lesser evil," and not born out of any political theory. "[I]t is superfluous to try, by the standard of theory, a part of the Constitution which is allowed on all hands to be the result, not of theory, but 'of a spirit of amity, and that mutual deference and concession which the peculiarity of our political situation rendered indispensable.'"

Even Gunning Bedford, Jr. of Delaware admitted that he only favored equal representation because it advanced the interests of his own state. "Can it be expected that the small states will act from pure disinterestedness? Are we to act with greater purity than the rest of mankind?"[7]

Once the issue of equal representation had been settled, the delegates addressed the size of the body: to how many senators would each state be entitled? Giving each state one senator was considered insufficient, as it would make the achievement of a quorum more difficult. A proposal from the Pennsylvania delegates for each state to elect three senators was discussed, but the resulting greater size was deemed a disadvantage. When the delegates voted on a proposal for two senators per state, all states supported this number.[8]

Since 1789, differences in population between states have become more pronounced. At the time of the Connecticut Compromise, the largest state, Virginia, had only twelve times the population of the smallest state, Delaware. Today, the largest state, California, has a population that is seventy times greater than the population of the smallest state, Wyoming. In 1790, it would take a theoretical 30% of the population to elect a majority of the Senate, today it would take 17%.

1789–1865

The Senate originally met, virtually in secret, on the second floor of Federal Hall in New York City in a room that allowed no spectators. For five years, no notes were published on Senate proceedings.

A procedural issue of the early Senate was what role the vice president, the President of the Senate, should have. The first vice president was allowed to craft legislation and participate in debates, but those rights were taken away relatively quickly. John Adams seldom missed a session, but later vice presidents made Senate attendance a rarity. Although the founders intended the Senate to be the slower legislative body, in the early years of the Republic, it was the House that took its time passing legislation. Alexander Hamilton's Bank of the United States and Assumption Bill (he was then Treasury Secretary), both of which were controversial, easily passed the Senate, only to meet opposition from the House.

In 1797, Thomas Jefferson began the vice presidential tradition of only attending Senate sessions on special occasions. Despite his frequent absences Jefferson did make his mark on the body with the Senate book of parliamentary procedure, his 1801 Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States, which is still used.

The decades before the American Civil War are thought of as the "Golden Age" of the Senate. Backed by public opinion and President Jefferson, in 1804, the House voted to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, 73–32. The Senate voted against conviction, 18–16.

The Senate seemed to bring out the best in Aaron Burr, who as vice president presided over the impeachment trial. At the conclusion of the trial Burr said:

This House is a sanctuary; a citadel of law, of order, and of liberty; and it is here–in this exalted refuge; here if anywhere, will resistance be made to the storms of political phrensy and the silent arts of corruption.[9]

Even Burr's many critics conceded that he handled himself with great dignity, and the trial with fairness.

Over the next few decades the Senate rose in reputation in the United States. John C. Calhoun, Daniel Webster, Thomas Hart Benton, Stephen A. Douglas, and Henry Clay overshadowed several presidents. Sir Henry Maine called the Senate "the only thoroughly successful institution which has been established since the tide of modern democracy began to run." William Ewart Gladstone said the Senate was "the most remarkable of all the inventions of modern politics."[10]

Among the greatest of debates in Senate history was the Webster–Hayne debate of January 1830, pitting the sectional interests of Daniel Webster's New England against Robert Y. Hayne's South.

During the pre-Civil War decades, the nation had two contentious arguments over the North–South balance in the Senate. Since the banning of slavery north of the Mason–Dixon line there had always been equal numbers of slave and free states. In the Missouri Compromise of 1820, brokered by Henry Clay, Maine was admitted to the Union as a free state to counterbalance Missouri. The Compromise of 1850, brokered by Henry Clay and Stephen Douglas, helped postpone the Civil War.

1865–1913

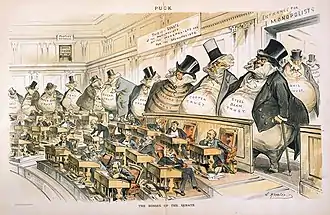

In the post-Civil War era, the Senate dealt with great national issues such as Reconstruction and monetary policy. Given the strong political parties of the Third Party System, the leading politicians controlled enough support in state legislatures to be elected Senators. In an age of unparalleled industrial expansion, entrepreneurs had the prestige previously reserved to victorious generals, and many were elected to the Senate.

In 1890–1910 a handful of Republicans controlled the chamber, led by Nelson Aldrich (Rhode Island), Orville H. Platt (Connecticut), John Coit Spooner (Wisconsin), William Boyd Allison (Iowa), along with national party leader Mark Hanna (Ohio). Aldrich designed all the major tax and tariff laws of the early 20th century, including the Federal reserve system. Among the Democrats Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland stood out.

From 1871 to 1898, the Senate did not approve any treaties. The Senate scuttled a long series of reciprocal trade agreements, blocked deals to annex the Dominican Republic and the Danish West Indies, defeated an arbitration deal with Britain, and forced the renegotiation of the pact to build the Panama Canal. Finally, in 1898, the Senate nearly refused to ratify the treaty that ended the Spanish–American War.

1913–1945

The Senate underwent several significant changes during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson, the most profound of which was the ratification of the 17th Amendment in 1913, which provided for election of senators by popular vote rather than appointment by the state legislatures.

Another change that occurred during the presidency of Woodrow Wilson was the limitation of the filibuster through the cloture vote. The filibuster was first used in the early Republic, but was seldom seen during most of the 19th century. It was limited as a response to the filibuster of the arming of merchant ships in World War I. At that time, the public, the House, the great majority of the Senate, and the president wanted merchant ships armed, but less than 20 Senators, led by William Jennings Bryan fought to keep US ships unarmed. Wilson denounced the group as a "group of willful men".

The post of Senate Majority Leader was also created during the Wilson presidency. Before this time, a Senate leader was usually a committee chairman, or a person of great eloquence, seniority, or wealth, such as Daniel Webster and Nelson Aldrich. However, despite this new, formal leadership structure, the Senate leader initially had virtually no power, other than priority of recognition from the presiding officer. Since the Democrats were fatally divided into northern liberal and southern conservative blocs, the Democratic leader had even less power than his title suggested.

Rebecca Felton was sworn in as a Senator for Georgia on November 21, 1922, and served one day; she was the first woman to serve in the Senate.[11]

Joseph T. Robinson of Arkansas, the Democratic leader from 1923 to 1937, saw it as his responsibility not to lead the Democrats, but to work the Senate for the president's benefit, no matter who the president was. When Coolidge and Hoover were president, he assisted them in passing Republican legislation. Robinson helped end government operation of Muscle Shoals, helped pass the Hoover Tariff, and stymied a Senate investigation of the Power Trust. Robinson switched his own position on a drought relief program for farmers when Hoover made a proposal for a more modest measure. Alben Barkley called Robinson's cave-in "the most humiliating spectacle that could be brought about in an intelligent legislative body." When Franklin Roosevelt became president, Robinson followed the new president as loyally as he had followed Coolidge and Hoover. Robinson passed bills in the Hundred Days so quickly that Will Rogers joked "Congress doesn't pass legislation any more, they just wave at the bills as they go by."[12]

In 1932 Hattie Caraway of Arkansas became the first woman elected to the Senate.[13]

In 1937 the Senate opposed Roosevelt's "court packing" plan and successfully called for reduced deficits.

Since 1945

The popular Senate drama of the early 1950s was Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy's investigations of alleged communists. After years of unchallenged power, McCarthy fell as a result of producing little hard evidence for his claims while the claims themselves became more elaborate, even questioning the leadership of the United States Army. McCarthy was censured by the Senate in 1954.

Prior to World War II, Senate majority leader had few formal powers. But in 1937, the rule giving majority leader right of first recognition was created. With the addition of this rule, the Senate majority leader enjoyed far greater control over the agenda of which bills to be considered on the floor.

During Lyndon Baines Johnson's tenure as Senate leader, the leader gained new powers over committee assignments.

In 1971 Paulette Desell was appointed by Senator Jacob K. Javits as the Senate's first female page.[14]

In 2009 Kathie Alvarez became the Senate's first female legislative clerk.[15]

See also

References

- American National Biography (1999) 20 volumes; contains scholarly biographies of all politicians no longer alive.

- Barone, Michael, and Grant Ujifusa, The Almanac of American Politics 1976: The Senators, the Representatives and the Governors: Their Records and Election Results, Their States and Districts (1975); new edition every 2 years, informal practices, and member information)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 2001–2004: A Review of Government and Politics: 107th and 108th Congresses (2005); summary of Congressional activity, as well as major executive and judicial decisions; based on Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report and the annual CQ almanac.

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1997–2001 (2002)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1993–1996 (1998)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1989–1992 (1993)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1985–1988 (1989)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1981–1984 (1985)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1977–1980 (1981)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1973–1976 (1977)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1969–1972 (1973)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1965–1968 (1969)

- Congressional Quarterly Congress and the Nation: 1945–1964 (1965), the first of the series

- Ashby, LeRoy and Gramer, Rod. Fighting the Odds: The Life of Senator Frank Church. Washington State U. Pr., 1994. Chair of Foreign Relations in the 1970s

- Becnel, Thomas A. Senator Allen Ellender of Louisiana: A Biography. Louisiana State U. Press, 1995.

- David W. Brady and Mathew D. McCubbins. Party, Process, and Political Change in Congress: New Perspectives on the History of Congress (2002)

- Caro, Robert A. The Years of Lyndon Johnson. Vol. 3: Master of the Senate. Knopf, 2002.

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr. Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations. Cambridge U. Press, 2001.

- Gould, Lewis L. The Most Exclusive Club: A History Of The Modern United States Senate (2005) the latest full-scale history by a scholar

- Hernon, Joseph Martin. Profiles in Character: Hubris and Heroism in the U.S. Senate, 1789–1990 Sharpe, 1997.

- Hoebeke, C. H. The Road to Mass Democracy: Original Intent and the Seventeenth Amendment. Transaction Books, 1995.

- Hunt, Richard. (1998). "Using the Records of Congress in the Classroom," OAH Magazine of History, 12 (Summer): 34–37.

- Johnson, Robert David. The Peace Progressives and American Foreign Relations. Harvard U. Press, 1995.

- McFarland, Ernest W. The Ernest W. McFarland Papers: The United States Senate Years, 1940–1952. Prescott, Ariz.: Sharlot Hall Museum, 1995. Democratic majority leader 1950–1952

- Malsberger, John W. From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938–1952. Susquehanna U. Press 2000.

- Mann, Robert. The Walls of Jericho: Lyndon Johnson, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Russell and the Struggle for Civil Rights. Harcourt Brace, 1996.

- O'Brien, Michael. Philip Hart: The Conscience of the Senate. Michigan State U. Press 1995.

- Rice, Ross R. Carl Hayden: Builder of the American West U. Press of America, 1993. Chair of Appropriations in the 1960s and 1970s

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Ritchie, Donald A. Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents. Harvard University Press, 1991.

- Ritchie, Donald A. The Congress of the United States: A Student Companion Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Ritchie, Donald A. Reporting from Washington: The History of the Washington Press Corps Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Swift, Elaine K. The Making of an American Senate: Reconstitutive Change in Congress, 1787–1841. U. of Michigan Press, 1996.

- Valeo, Frank. Mike Mansfield, Majority Leader: A Different Kind of Senate, 1961–1976 Sharpe, 1999. Senate majority leader.

- Weller, Cecil Edward, Jr. Joe T. Robinson: Always a Loyal Democrat. U. of Arkansas Press, 1998. Majority leader in the 1930s

- Wirls, Daniel and Wirls, Stephen. The Invention of the United States Senate Johns Hopkins U. Press, 2004.

- Julian E. Zelizer. On Capitol Hill : The Struggle to Reform Congress and its Consequences, 1948–2000 (2006)

- Julian E. Zelizer. ed. The American Congress: The Building of Democracy (2004)

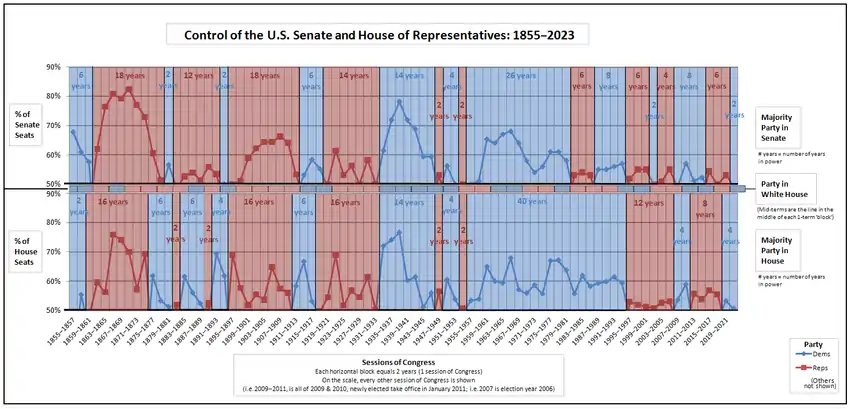

- "Party In Power – Congress and Presidency – A Visual Guide To The Balance of Power In Congress, 1945–2008". Uspolitics.about.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- Richard N. Rosenfeld

- Harpers, May 2004, p42

- The Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787 by James Madison

- Harper's Magazine, May 2004, 36.

- New Republic, August 7, 2002.

- Sizing Up the Senate, 33.

- The Senate and the United States Constitution, United States Senate, undated. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- Master of the Senate, 14.

- Master of the Senate, 23.

- David B. Parker, "Rebecca Latimer Felton (1835–1930)," New Georgia Encyclopedia (2010) online

- Master of the Senate, 354–55

- "CARAWAY, Hattie Wyatt – Biographical Information". Bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- "U.S. Senate - No HTTPS" (PDF). Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- "Kathie Alvarez, the Senate's first female legislative clerk, retires". Fox News Latino. Retrieved 2015-02-15.

Official Senate histories

- Published by the Senate Historical Office

- Robert C. Byrd. The Senate, 1789–1989. Four volumes.

- Vol. I, a chronological series of addresses on the history of the Senate. (stock number 052-071-00823-3)

- Vol. II, a topical series of addresses on various aspects of the Senate's operation and powers. (stock number 052-071-00856-0)

- Vol. III, Classic Speeches, 1830–1993. (stock number 052-071-01048-3)

- Vol. IV, Historical Statistics, 1789–1992. (stock number 052-071-00995-7)

- Booknotes interview with Byrd on The Senate: 1789–1989, June 18, 1989.

- Bob Dole. Historical Almanac of the United States Senate. (stock number 052-071-00857-8).

- Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774–1989, (stock number 052-071-00699-1)

- Mark O. Hatfield, with the Senate Historical Office. Vice Presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. (stock number 052-071-01227-3); essays reprinted online

- The United States Senate