DeSoto County, Mississippi

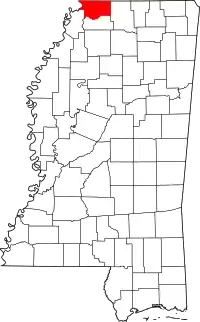

DeSoto County is a county located on the northwest border of the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 161,252,[1] making it the third-most populous county in Mississippi. Its county seat is Hernando.[2]

DeSoto County | |

|---|---|

DeSoto County Courthouse | |

Location within the U.S. state of Mississippi | |

Mississippi's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 34°53′N 89°59′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | February 9, 1836 |

| Named for | Hernando de Soto |

| Seat | Hernando |

| Largest city | Southaven |

| Area | |

| • Total | 497 sq mi (1,290 km2) |

| • Land | 476 sq mi (1,230 km2) |

| • Water | 21 sq mi (50 km2) 4.2% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 161,252 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 184,945 |

| • Density | 320/sq mi (130/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | www |

DeSoto County is part of the Memphis, TN-MS-AR Metropolitan Statistical Area. It is the second-most populous county in the MSA. The county has lowland areas that were developed in the 19th century for cotton plantations, and hill country in the eastern part of the county.[3]

History

The county is named for Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto, the first European explorer known to reach the Mississippi River.[4] The county seat, Hernando, is also named in his honor. De Soto reportedly died in that area in May 1542, although some accounts suggest that he died near Lake Village, Arkansas. See here for a list of sites associated with the 16th-century De Soto Expedition.

Early history

Indian artifacts collected in DeSoto County link it with prehistoric groups of Woodland and Mississippian culture peoples. Members of the Mississippian culture, who built complex settlements and earthwork monuments throughout the Mississippi River Valley and its major tributaries, met Hernando DeSoto in the mid-16th century when he explored what is now North Mississippi. By tradition, he is believed to have traveled with his expedition through present-day DeSoto County. Some scholars speculate that DeSoto discovered the Mississippi River west of present-day Lake Cormorant, built rafts there, and crossed to present-day Crowley's Ridge, Arkansas. Based on records of the expedition and archeology, the National Park Service has designated a "DeSoto Corridor" from Coahoma County, Mississippi to the Chickasaw Bluff in Memphis.

The Mississippian culture declined and disappeared, and in most areas this preceded European contact. Scholars speculate this may have followed changes in the environment. The town named Chicasa, which De Soto visited, was probably the ancestral home of the historical Chickasaw, who are descended from the Mississippian culture. They had lived in the area for centuries before white settlers began arriving. Present-day Pontotoc, Mississippi developed near the Chickasaw "Long Town," which was composed of several villages near each other. The Chickasaw Nation regarded much of western present-day Tennessee and northern Mississippi as their traditional hunting grounds.

The Chickasaw traded furs for French goods, and the French established several small settlements among them. However, France ceded its claim to territories east of the Mississippi River to Britain in 1763, after having been defeated in the Seven Years' War. The United States acquired the area from the British as part of the treaty that ended the American Revolution.

19th-20th centuries

The Chickasaw finally ceded most of their land to the United States under pressure during Indian Removal, and a treaty in 1832. They were forced to remove to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Negotiations began in September 1816 between the United States government and the Chickasaw nation, and concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Pontotoc in October 1832. During these 16 years, federal officials pressed the Chickasaw for cessions of land to extinguish their land claims, in order to enable white settlement in their territory. Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, authorizing forcible removal if necessary to extinguish Native American claims in the Southeast. From 1832 to 1836, government surveyors mapped the 6,442,000 acres (26,070 km2) of the Chickasaw domain, dividing it into townships, ranges and sections. The Mississippi Legislature formed 10 new counties, including DeSoto, Tunica, Marshall, and Tate, from this territory.

By treaty the land was assigned by sections of 640 acres (2.6 km2) to individual Indian households. The Chickasaw, a numerically small tribe, were assigned 2,422,400 acres (9,803 km2) of land using this formula. The government declared the remainder as surplus and disposed of these remaining 400,000 acres (1,600 km2) at public sale. The Indians received at least $1.25 per acre for their land. The government land sold for 75 cents per acre or less.

During and after the Civil War, this area was developed as large plantations by planters for cultivation of cotton, a leading commodity crop. Before the Civil War they depended on the labor of thousands of enslaved African Americans. After the war and emancipation, many freedmen stayed in the area, but shaped their own lives by working on small plots as sharecroppers or tenant farmers, rather than on large labor gangs on the plantations. Reliance on agriculture meant that the area did not develop much economically well into the 20th century, and both whites and blacks suffered economically.

In 1890 the state legislature disenfranchised most blacks under the new constitution, which used poll taxes and literacy tests to raise barriers to voter registration. In the early 20th century, many people left the rural county for cities to gain other opportunities. Most blacks could not vote in Mississippi until the late 1960s, after passage of federal legislation.

.jpg.webp)

During the Great Depression, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union was organized in 1934; it was open to both black and white sharecroppers. It worked to gain better deals and fair accounting from local white landowners. Whites in DeSoto County resisted this effort. In 1935, a white lynch mob attacked early union organizer and minister Reverend T. A. Allen, shooting him and throwing him into the Coldwater River. One account said that his body was weighted by chains, and that authorities claimed he was a "suicide".[6]

In its 2015 report on Lynching in America (2015), the Equal Justice Institute documented 12 lynchings in the county from 1877 to 1950.[7] Most lynchings in the South took place around the turn of the 20th century.[7]

Since the late 20th century, DeSoto has had considerable suburban development related to the growth of Memphis.

2000 to present

As part of the Memphis, Tennessee metropolitan area, in the early 21st century DeSoto County has become one of the 40 fastest-growing counties in the United States. This fast-paced growth is attributed to suburban development, as middle-class and wealthier blacks leave Memphis to acquire newer housing. They commute to Memphis for work. Some observers have characterized this shift as black flight, but it is also typical of the pattern of post-World War II suburban growth, in which people who could afford it moved to newer housing in suburbs.[8]

Such suburban residential development in the county has been most noticeable in the cities of Southaven, Olive Branch and Horn Lake, Mississippi. Also stimulating development in the formerly rural area is the massive casino/resort complex located in neighboring Tunica County (this is the third-largest gambling district in the United States).

Politics

The majority-white voters in DeSoto County increasingly favored Republican presidential candidates from 1980 to 2000, but changing demographics could affect that. White conservatives in the state had shifted from the Democratic Party to the Republican Party following passage of civil rights legislation in the mid-1960s. At the same time, given the increase in whites in the county and some outmigration by blacks, their number and percentage of population in the county declined. African Americans have generally supported the Democratic Party since passage of civil rights legislation. By 2000 they comprise 11% of the county population.

But beginning in 2004, the Democratic Party candidates have shown renewed strength in the county, attracting more votes than the percentage of African Americans in the population. During this period, the proportion of African Americans in the county has increased. The voting has continued to show racial polarization, with most whites voting for Republican candidates. As of 2013 census estimates, African Americans made up slightly more than 21% of the county population.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 61.0% 46,462 | 37.1% 28,265 | 1.8% 1,397 |

| 2016 | 65.1% 43,089 | 31.1% 20,591 | 3.7% 2,475 |

| 2012 | 66.2% 43,559 | 32.8% 21,575 | 1.0% 660 |

| 2008 | 68.8% 44,222 | 30.5% 19,627 | 0.7% 474 |

| 2004 | 72.3% 36,306 | 27.1% 13,583 | 0.7% 326 |

| 2000 | 71.2% 24,879 | 27.4% 9,586 | 1.3% 471 |

| 1996 | 53.5% 18,135 | 30.4% 10,282 | 16.1% 5,464 |

| 1992 | 58.4% 16,104 | 32.0% 8,833 | 9.6% 2,638 |

| 1988 | 72.5% 14,681 | 26.9% 5,449 | 0.6% 120 |

| 1984 | 73.9% 12,576 | 25.7% 4,369 | 0.5% 77 |

| 1980 | 58.8% 9,655 | 38.6% 6,344 | 2.6% 420 |

| 1976 | 43.6% 6,240 | 54.2% 7,756 | 2.2% 316 |

| 1972 | 80.9% 7,917 | 15.9% 1,557 | 3.2% 315 |

| 1968 | 13.1% 1,092 | 22.8% 1,898 | 64.1% 5,346 |

| 1964 | 86.4% 2,928 | 13.6% 461 | |

| 1960 | 26.6% 553 | 38.2% 795 | 35.3% 734 |

| 1956 | 21.6% 398 | 67.0% 1,236 | 11.5% 212 |

| 1952 | 36.9% 754 | 63.1% 1,288 | |

| 1948 | 1.0% 14 | 9.5% 137 | 89.6% 1,299 |

| 1944 | 7.3% 123 | 92.7% 1,561 | |

| 1940 | 2.6% 40 | 97.1% 1,491 | 0.3% 4 |

| 1936 | 1.0% 13 | 99.0% 1,343 | |

| 1932 | 0.9% 13 | 98.8% 1,396 | 0.3% 4 |

| 1928 | 4.5% 64 | 95.5% 1,357 | |

| 1924 | 1.6% 17 | 98.4% 1,065 | |

| 1920 | 3.2% 27 | 96.6% 816 | 0.2% 2 |

| 1916 | 1.4% 12 | 98.5% 861 | 0.1% 1 |

| 1912 | 1.7% 10 | 94.6% 546 | 3.6% 21 |

| 1908 | |||

| 1904 | |||

| 1900 | 6.5% 51 | 92.9% 734 | 0.6% 5 |

| 1896 | 6.0% 58 | 91.7% 888 | 2.3% 22 |

| 1892 | 2.9% 18 | 77.9% 478 | 19.2% 118 |

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 497 square miles (1,290 km2), of which 476 square miles (1,230 km2) is land and 21 square miles (54 km2) (4.2%) is water.[10]

Geographic features

Major highways

I-55 recently underwent major widening from four lanes to ten from the MS/TN state line south to Goodman Road. Eventual widening of the freeway from Goodman Rd. to Commerce St. will include the addition of a new exit at Star Landing Rd.

I-269 is a metro Memphis outer loop connecting the cities of Hernando and Olive Branch in Mississippi with Collierville and Millington in Tennessee.

Adjacent counties

- Shelby County, Tennessee - north

- Crittenden County, Arkansas - west

- Tunica County - south

- Tate County - south

- Marshall County - east

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 7,002 | — | |

| 1850 | 19,042 | 172.0% | |

| 1860 | 23,336 | 22.6% | |

| 1870 | 32,021 | 37.2% | |

| 1880 | 22,924 | −28.4% | |

| 1890 | 24,183 | 5.5% | |

| 1900 | 24,751 | 2.3% | |

| 1910 | 23,130 | −6.5% | |

| 1920 | 24,359 | 5.3% | |

| 1930 | 25,438 | 4.4% | |

| 1940 | 26,663 | 4.8% | |

| 1950 | 24,599 | −7.7% | |

| 1960 | 23,891 | −2.9% | |

| 1970 | 35,885 | 50.2% | |

| 1980 | 53,930 | 50.3% | |

| 1990 | 67,910 | 25.9% | |

| 2000 | 107,199 | 57.9% | |

| 2010 | 161,252 | 50.4% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 184,945 | [11] | 14.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] 1790-1960[13] 1900-1990[14] 1990-2000[15] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the 2013 U.S.census estimates, there were 168,240 people living in the county. 70.3% were non-Hispanic White, 21.5% Black or African American, 1.6% Asian, 2.6% Native American, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 5.0% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race).[16] The median income for a family was $66,377 and the mean income was $75,875.[17] DeSoto County has the highest median income in Mississippi and the second highest mean income after Madison County.

According to the 2000 census,[18] the largest self-identified ancestry groups in DeSoto County were English 53.1%, Scots-Irish 15.1%, African 11.4%, and Irish 4.5%. Since then the percentage of African-American population in the county has nearly doubled, as the total county population has also grown.

Attractions

DeSoto County is known for its golf courses. Velvet Cream, known as 'The Dip' by locals, is a landmark restaurant in the county. Operating since 1947, it is the oldest continually running restaurant in the county. In 2010, it was awarded 'Best Ice Cream in Mississippi' by USA Today.[19] DeSoto County was also previously known as the home of Maywood Beach, a water park that closed in 2003 after more than 70 years of operation.

DeSoto County Museum

A popular attraction is the DeSoto County Museum located in the county seat of Hernando. The museum is open Tuesday through Saturday from 10–5. Admission is free but donations are encouraged. Exhibits include displays on Hernando DeSoto, Civil War history, French colonial and American antebellum homes of the county, civil rights, and the history of each of the county's municipalities.[20]

An eighteenth-century French colonial log house (see photo to the right) has been preserved from the time of French trading and settlement along the Mississippi. This house is similar in style to several French colonial houses preserved in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, where many French settled after France ceded its territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain following its defeat in the Seven Years' War.

Hernando DeSoto Park

Hernando DeSoto Park, located on Bass Road 6 mi (9.7 km) west of Walls, is a 41 acres (17 ha) park that features a hiking/walking trail, river overlook, picnic area, and boat launch. It is the only location in DeSoto County with public access to the Mississippi River.[21]

Communities

Cities

- Hernando (county seat)

- Horn Lake

- Olive Branch

- Southaven

Towns

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

Former village

Notable people

- John Grisham, lawyer, writer.

- Olivia Holt, actor, singer.

Media

- DeSoto Times-Tribune

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in DeSoto County, Mississippi

- Bill Hawks, agribusinessman and former state senator from DeSoto County

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- "Scenic Byways". Archived from the original on 2014-10-27.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 105.

- [ Michael Newton, Unsolved Civil Rights Murder Cases, 1934-1970, McFarland, 2016, p. 102

- Lynching in America, 2nd edition Archived 2018-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, Supplement by County, p. 5

- Henry Bailey (February 4, 2011). "'Black flight' propels DeSoto County growth, census figures show". Commercial Appeal. Memphis, Tennessee. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "American FactFinder". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 3, 2014.

- Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "U.S. Census website".

- Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder - Results". Archived from the original on 2020-02-12.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "The USA's best ice cream: Top parlors in 50 states". USA Today. August 29, 2010.

- Bryant, Josh. "DeSoto County Museum - Explore our heritage". www.desotomuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- "Hernando DeSoto Park". DeSoto County Greenways and Parks. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

Suggested reading

- Map Guide to the U.S. Federal Censuses, 1790–1920, Thorndale, William, and Dollarhide, William; Copyright 1987. (Historic state maps including evolution of DeSoto County)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to DeSoto County, Mississippi. |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about DeSoto County, Mississippi. |

- DesotoCountyMS.gov - Official County Government Website

- DeSoto County Economic Development Council - Official site.

.svg.png.webp)