Drill

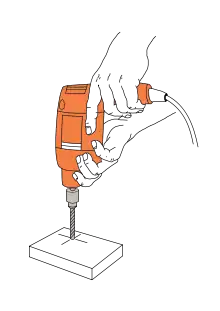

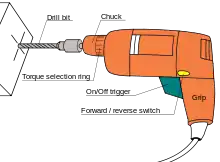

A drill or drilling machine is a tool primarily used for making round holes or driving fasteners. It is fitted with a bit, either a drill or driver, depending on application, secured by a chuck. Some powered drills also include a hammer function.

Drills vary widely in speed, power, and size. They are characteristically corded electrically driven devices, with hand-operated types dramatically decreasing in popularity and cordless battery-powered ones proliferating.

Drills are commonly used in woodworking, metalworking, construction, machine tool fabrication, construction and utility projects. Specially designed versions are made for medicine, space, and miniature applications.

History

Around 35,000 BC, Homo sapiens discovered the benefits of the application of rotary tools. This would have rudimentarily consisted of a pointed rock being spun between the hands to bore a hole through another material.[1] This led to the hand drill, a smooth stick, that was sometimes attached to flint point, and was rubbed between the palms. This was used by many ancient civilizations around the world including the Mayans.[2] The earliest perforated artifacts, such as bone, ivory, shells, and antlers found, are from the Upper Paleolithic era.[3]

Bow drill (strap-drills) are the first machine drills, as they convert a back and forth motion to a rotary motion, and they can be traced back to around 10,000 years ago. It was discovered that tying a cord around a stick, and then attaching the ends of the string to the ends of a stick (a bow), allowed a user to drill quicker and more efficiently. Mainly used to create fire, bow-drills were also used in ancient woodwork, stonework, and dentistry. Archaeologists discovered a Neolithic grave yard in Mehrgarh, Pakistan dating from the time of the Harappans, around 7,500–9,000 years ago, containing 9 adult bodies with a total of 11 teeth that had been drilled.[4] There are hieroglyphs depicting Egyptian carpenters and bead makers in a tomb at Thebes using bow-drills. The earliest evidence of these tools being used in Egypt dates back to around 2500 BCE.[5] The usage of bow-drills was widely spread through Europe, Africa, Asia, and North America, during ancient times and is still used today. Over the years many slight variations of bow and strap drills have developed for the various uses of either boring through materials or lighting fires.

The core drill was developed in ancient Egypt by 3000 BC.[6] The pump drill was invented during Roman times. It consists of a vertical spindle aligned by a piece of horizontal wood and a flywheel to maintain accuracy and momentum.[7]

The hollow-borer tip, first used around the 13th century, consisted of a stick with a tubular shaped piece of metal on the end, such as copper. This allowed a hole to be drilled while only actually grinding the outer section of it. This completely separates the inner stone or wood from the rest, allowing the drill to pulverize less material to create a similarly sized hole.[8]

While the pump-drill and the bow-drill were used in Western Civilization to bore smaller holes for a larger part of human history, the Auger was used to drill larger holes starting sometime between Roman and Medieval ages.[9] The auger allowed for more torque for larger holes. It is uncertain when the Brace and Bit was invented; however, the earliest picture found so far dates from the 15th century.[9] It is a type of hand crank drill that consists of two parts as seen in the picture. The brace, on the upper half, is where the user holds and turns it and on the lower part is the bit. The bit is interchangeable as bits wear down. The auger uses a rotating helical screw similar to the Archimedean screw-shaped bit that is common today. The gimlet is also worth mentioning as it is a scaled down version of an auger.

In the East, churn drills were invented as early as 221 BC during the Chinese Qin Dynasty,[10] capable of reaching a depth of 1500 m.[6] Churn drills in ancient China were built of wood and labor-intensive, but were able to go through solid rock.[11] The churn drill appears in Europe during the 12th century.[6] In 1835 Isaac Singer is reported to have built a steam powered churn drill based on the method the Chinese used.[12] Also worth briefly discussing are the early drill presses; they were machine tools that derived from bow-drills but were powered by windmills or water wheels. Drill presses consisted of the powered drills that could be raised or lowered into a material, allowing for less force by the user.

The next great advancement in drilling technology, the electric motor, led to the invention of the electric drill. It is credited to Arthur James Arnot and William Blanch Brain of Melbourne, Australia who patented the electric drill in 1889.[13] In 1895, the first portable handheld drill was created by brothers Wilhem & Carl Fein of Stuttgart, Germany. In 1917 the first trigger-switch, pistol-grip portable drill was patented by Black & Decker.[14] This was the start of the modern drill era. Over the last century the electric drill has been created in a variety of types and multiple sizes for an assortment of specific uses.

Types

There are many types of drills: some are powered manually, others use electricity (electric drill) or compressed air (pneumatic drill) as the motive power, and a minority are driven by an internal combustion engine (for example, earth drilling augers). Drills with a percussive action (hammer drills) are mostly used in hard materials such as masonry (brick, concrete and stone) or rock. Drilling rigs are used to bore holes in the earth to obtain water or oil. Oil wells, water wells, or holes for geothermal heating are created with large drilling rigs. Some types of hand-held drills are also used to drive screws and other fasteners. Some small appliances that have no motor of their own may be drill-powered, such as small pumps, grinders, etc.

Primitive

Some forms of drills have been used since the Pre-History, both to make holes in hard objects or as fire drills.

- Awl - The shaft is twisted with one hand

- Hand drill - The shaft is spun by rubbing motion of the hands

- Bow drill - The shaft is spun by cord of a bow that is moved back and forth.

- Pump drill - The shaft is spun by pushing down on a hand bar and by a flywheel

Hand-powered

Hand-powered metal drills have been in use for centuries. They include:

- Auger - a straight shaft with a wood-cutting blade at the bottom and a T-shaped handle

- Brace - a modified auger powered by means of a crankshaft

- Gimlet

- Bradawl, similar to a screwdriver but with a drilling point

- Wheel brace or hand drill, also known as an "eggbeater" drill

- Cranial drill is an instrument used throughout skull surgery

- Breast, similar to an "eggbeater" drill, it has a flat chest piece instead of a handle

- Push, which uses a spiral ratchet mechanism

- Pin chuck, a small hand-held jeweler's drill

Power drills

Drills powered by electriciy (or more rarely, compressed air) are the most common tools in woodworking and machining shops.

Electric drills can be corded (fed from an electric outlet through a power cable) or cordless (fed by rechargeable electric batteries). The latter have removable battery packs that can be swapped to allow uninterrupted drilling while recharging.

A popular use of hand-held power drills is to set screws into wood, through the use of screwdriver bits. Drills optimized for this purpose have a clutch to avoid damaging the slots on the screw head.

- Pistol-grip drill - the most common hand-held power drill type.

- Right-angle drill - used to drill ordrive screws in tight spaces.

- Hammer drill - combines rotary motion with a hammer action for drilling masonry. The hammer action may be engaged or disengaged as required.

- Drill press - larger power drill with a rigid holding frame, standalone mounted on a bench

- Rotary hammer combines a primary dedicated hammer mechanism with a separate rotation mechanism, and is used for more substantial material such as masonry or concrete.

Most electric hammer drills are rated (input power) at between 600 and 1100 watts. The efficiency is usually 50-60% i.e. 1000 watts of input is converted into 500-600 watts of output (rotation of the drill and hammering action).

For much of the 20th century, attachments could commonly be purchased to convert corded electric hand drills into a range of other power tools, such as orbital sanders and power saws, more cheaply than purchasing dedicated versions of those tools. As the prices of power tools and suitable electric motors have fallen such attachments have become much less common.

Early cordless drills used interchangeable 7.2 V battery packs. Over the years battery voltages have increased, with 18 V drills being most common, but higher voltages are available, such as 24 V, 28 V, and 36 V. This allows these tools to produce as much torque as some corded drills.

Common battery types of are nickel-cadmium (NiCd) batteries and lithium-ion batteries, with each holding about half the market share. NiCd batteries have been around longer, so they are less expensive (their main advantage), but have more disadvantages compared to lithium-ion batteries. NiCd disadvantages are limited life, self-discharging, environment problems upon disposal, and eventually internally short circuiting due to dendrite growth. Lithium-ion batteries are becoming more common because of their short charging time, longer life, absence of memory effect, and low weight. Instead of charging a tool for an hour to get 20 minutes of use, 20 minutes of charge can run the tool for an hour in average. Lithium-ion batteries also hold a charge for a significantly longer time than nickel-cadmium batteries, about two years if not used, vs. 1 to 4 months for a nickel-cadmium battery.

Hammer drill

The hammer action of a hammer drill is provided by two cam plates that make the chuck rapidly pulse forward and backward as the drill spins on its axis. This pulsing (hammering) action is measured in Blows Per Minute (BPM) with 10,000 or more BPMs being common. Because the combined mass of the chuck and bit is comparable to that of the body of the drill, the energy transfer is inefficient and can sometimes make it difficult for larger bits to penetrate harder materials such as poured concrete. A standard hammer drill accepts 6 mm (1/4 inch) and 13 mm (1/2 inch) drill bits. The operator experiences considerable vibration, and the cams are generally made from hardened steel to avoid them wearing out quickly. In practice, drills are restricted to standard masonry bits up to 13 mm (1/2 inch) in diameter. A typical application for a hammer drill is installing electrical boxes, conduit straps or shelves in concrete.

Rotary hammer

The rotary hammer (also known as a rotary hammer drill, roto hammer drill or masonry drill) . Generally, standard chucks and drills are inadequate and chucks such as SDS and carbide drills that have been designed to withstand the percussive forces are used. A rotary hammer uses SDS or Spline Shank bits. These heavy bits are adept at pulverising the masonry and drill into this hard material with relative ease. Some styles of this tool are intended for masonry drilling only and the hammer action cannot be disengaged. Other styles allow the drill to be used without the hammer action for normal drilling, or hammering to be used without rotation for chiselling. In 1813 Richard Trevithick designed a steam-driven rotary drill, also the first drill to be powered by steam.[15]

In contrast to the cam-type hammer drill, a rotary/pneumatic hammer drill accelerates only the bit. This is accomplished through a piston design, rather than a spinning cam. Rotary hammers have much less vibration and penetrate most building materials. They can also be used as "drill only" or as "hammer only" which extends their usefulness for tasks such as chipping brick or concrete. Hole drilling progress is greatly superior to cam-type hammer drills, and these drills are generally used for holes of 19 mm (3/4 inch) or greater in size. A typical application for a rotary hammer drill is boring large holes for lag bolts in foundations, or installing large lead anchors in concrete for handrails or benches.

Drill press

A drill press (also known as a pedestal drill, pillar drill, or bench drill) is a style of drill that may be mounted on a stand or bolted to the floor or workbench. Portable models are made, some including a magnetic base. Major components include a base, column (or pillar), adjustable table, spindle, chuck, and drill head, usually driven by an electric motor. The head typically has a set of three handles radiating from a central hub that are turned to move the spindle and chuck vertically. A drill press is typically measured by its "swing", calculated as twice the distance from the center of the chuck to the closest edge of the column. Thus, a tool with 4" between chuck center and column edge is described as an 8" drill press.

A drill press has a number of advantages over a hand-held drill:

- Less effort is required to apply the drill to the workpiece. The movement of the chuck and spindle is by a lever working on a rack and pinion, which gives the operator considerable mechanical advantage

- The table allows a vise or clamp to be used to position and restrain the work, making the operation much more secure

- The angle of the spindle is fixed relative to the table, allowing holes to be drilled accurately and consistently

- Drill presses are almost always equipped with more powerful motors compared to hand-held drills. This enables larger drill bits to be used and also speeds up drilling with smaller bits.

For most drill presses—especially those meant for woodworking or home use—speed change is achieved by manually moving a belt across a stepped pulley arrangement. Some drill presses add a third stepped pulley to increase the number of available speeds. Modern drill presses can, however, use a variable-speed motor in conjunction with the stepped-pulley system. Medium-duty drill presses such as those used in machine shop (tool room) applications are equipped with a continuously variable transmission. This mechanism is based on variable-diameter pulleys driving a wide, heavy-duty belt. This gives a wide speed range as well as the ability to change speed while the machine is running. Heavy-duty drill presses used for metalworking are usually of the gear-head type described below.

Drill presses are often used for miscellaneous workshop tasks other than drilling holes. This includes sanding, honing, and polishing. These tasks can be performed by mounting sanding drums, honing wheels and various other rotating accessories in the chuck. This can be unsafe in some cases, as the chuck arbor, which may be retained in the spindle solely by the friction of a taper fit, may dislodge during operation if the side loads are too high.

Geared head

A geared head drill press transmits power from the motor to the spindle through spur gearing inside the machine's head, eliminating a flexible drive belt. This assures a positive drive at all times and minimizes maintenance. Gear head drills are intended for metalworking applications where the drilling forces are higher and the desired speed (RPM) is lower than that used for woodworking.

Levers attached to one side of the head are used to select different gear ratios to change the spindle speed, usually in conjunction with a two- or three-speed motor (this varies with the material). Most machines of this type are designed to be operated on three-phase electric power and are generally of more rugged construction than equivalently sized belt-driven units. Virtually all examples have geared racks for adjusting the table and head position on the column.

Geared head drill presses are commonly found in tool rooms and other commercial environments where a heavy duty machine capable of production drilling and quick setup changes is required. In most cases, the spindle is machined to accept Morse taper tooling for greater flexibility. Larger geared head drill presses are frequently fitted with power feed on the quill mechanism, with an arrangement to disengage the feed when a certain drill depth has been achieved or in the event of excessive travel. Some gear-head drill presses have the ability to perform tapping operations without the need for an external tapping attachment. This feature is commonplace on larger gear head drill presses. A clutch mechanism drives the tap into the part under power and then backs it out of the threaded hole once the proper depth is reached. Coolant systems are also common on these machines to prolong tool life under production conditions.

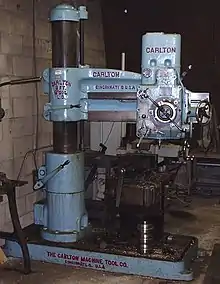

Radial arm

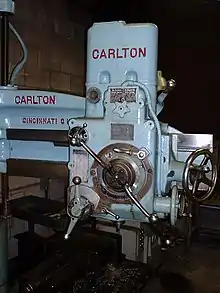

A radial arm drill press is a large geared-head drill press in which the head can be moved along an arm that radiates from the machine's column. As it is possible to swing the arm relative to the machine's base, a radial arm drill press is able to operate over a large area without having to reposition the workpiece. This feature saves considerable time because it is much faster to reposition the machine's head than it is to unclamp, move, and then re-clamp the workpiece to the table. The size of work that can be handled may be considerable, as the arm can swing out of the way of the table, allowing an overhead crane or derrick to place a bulky workpiece on the table or base. A vise may be used with a radial arm drill press, but more often the workpiece is secured directly to the table or base, or is held in a fixture.

Power spindle feed is nearly universal with these machines and coolant systems are common. Larger-size machines often have power feed motors for elevating or moving the arm. The biggest radial arm drill presses are able to drill holes as large as four inches (101.6 millimeters) diameter in solid steel or cast iron. Radial arm drill presses are specified by the diameter of the column and the length of the arm. The length of the arm is usually the same as the maximum throat distance. The radial arm drill press pictured to the right has a 9 inch diameter and a 3 foot long arm. The maximum throat distance of this machine would be approximately 36", giving a maximum swing of 72" (6 feet or 1.83 meters).

Magnetic drill press

A magnetic drill is a portable machine for drilling holes in large and heavy workpieces which are difficult to move or bring to a stationary conventional drilling machine. It has a magnetic base and drills holes with the help of cutting tools like annular cutters (broach cutters) or with twist drill bits. There are various types depending on their operations and specializations, like magnetic drilling cum tapping machines, cordless, pneumatic, compact horizontal, automatic feed, cross table base etc.

Mill

Mill drills are a lighter alternative to a milling machine. They combine a drill press (belt driven) with the X/Y coordinate abilities of the milling machine's table and a locking collet that ensures that the cutting tool will not fall from the spindle when lateral forces are experienced against the bit. Although they are light in construction, they have the advantages of being space-saving and versatile as well as inexpensive, being suitable for light machining that may otherwise not be affordable.

Surgical

Drills are used in surgery to remove or create holes in bone; specialties that use them include dentistry, orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. The development of surgical drill technology has followed that of industrial drilling, including transitions to the use of lasers, endoscopy, use of advanced imaging technologies to guide drilling, and robotic drills.[16][17][18][19]

Accessories

Drills are often used simply as motors to drive a variety of applications, in much the same way that tractors with generic PTOs are used to power ploughs, mowers, trailers, etc.

Accessories available for drills include:

- Screw-driving tips of various kinds - flathead, Philips, etc. for driving screws in or out

- Water pumps

- Nibblers for cutting metal sheet

- Rotary sanding discs

- Rotary polishing discs

- Rotary cleaning brushes

Capacity

Drilling capacity indicates the maximum diameter a given power drill or drill press can produce in a certain material. It is essentially a proxy for the continuous torque the machine is capable of producing. Typically a given drill will have its capacity specified for different materials, i.e., 10mm for steel, 25mm for wood, etc.

For example, the maximum recommended capacities for the DeWalt DCD790 cordless drill for specific drill bit types and materials are as follows:[20]

| Material | Drill bit type | Capacity |

|---|---|---|

| Wood | Auger | 7⁄8 in (22 mm) |

| Paddle | 1 1⁄4 in (32 mm) | |

| Twist | 1⁄2 in (13 mm) | |

| Self-feed | 1 3⁄8 in (35 mm) | |

| Hole saw | 2 in (51 mm) | |

| Metal | Twist | 1⁄2 in (13 mm) |

| Hole saw | 1 3⁄8 in (35 mm) |

References

- Roger Bridgeman. 1000 Inventions and Discoveries. The Smithsonian Institution. DK. New York; 2006. p7

- Charles Singer; E. J. Holmyard and A. R. Hall. A History of Technology, Volume 1: From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires. Oxford University Press; London, England. 1967. p. 189

- Charles Singer; E. J. Holmyard and A. R. Hall. A History of Technology, Volume 1: From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires. Oxford University Press; London, England.1967. p. 188

- A, Coppa. "Early Neolithic tradition of dentistry: Flint tips were surprisingly effective for dialing tooth enamel in a prehistoric population." Nature. (April 6, 2006.); p755-6

- Charles Singer;E. J. Holmyard and A. R. Hall. A History of Technology, Volume 1: From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires. Oxford University Press; London, England. 1967. p. 190

- Jacques W. Delleur (12 December 2010). The Handbook of Groundwater Engineering, Second Edition. Taylor & Francis. p. 7 in chapter 2. ISBN 978-0-8493-4316-2.

- Charles Singer; E. J. Holmyard and A. R. Hall. A History of Technology, Volume 1: From Early Times to Fall of Ancient Empires. Oxford University Press; London, England. 1967 p. 226

- Trans. Eileen B. Hennyessy, Ed. Maurice, Daumas. A History of Technology & Invention: Progress Through the Ages, Volume 1: The Origins of Technological Civilization. Crown Publishers, Inc; New York. 1969

- Trans. Eileen B. Hennyessy, Ed. Maurice, Daumas. A History of Technology & Invention: Progress Through the Ages, Volume 1: The Origins of Technological Civilization. Crown Publishers, Inc; New York. 1969 p.502

- Geng Ruilun (1 October 1997). Guo Huadong (ed.). New Technology for Geosciences: Proceedings of the 30th International Geological Congress. VSP. p. 225. ISBN 978-90-6764-265-1.

- James E. Landmeyer (15 September 2011). Introduction to Phytoremediation of Contaminated Groundwater: Historical Foundation, Hydrologic Control, and Contaminant Remediation. Springer. p. 112. ISBN 978-94-007-1956-9.

- Alban J. Lynch; Chester A. Rowland (2005). The History of Grinding. p.173

- "Specifications for registration of patent by William Blanch Brain and Arthur James Arnot titled - Improvements in electrical rock drills coal diggers and earth cutters" National Archives of Australia.1889 Retrieved 1 April 2006

- US patent 1,245,860, S.D. Black & A.G. Decker, "Electrically driven tool", issued 1917-11-06

- Burton, Anthony (1 February 2013). History's Most Dangerous Jobs Miners. History Press. ISBN 9780752492254. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- Durand, R.; Voyer, R. (2018). "Step-by-Step Surgical Considerations and Techniques.". In Emami, E.; Feine J., J. (eds.). Mandibular implant prostheses. Springer. pp. 107–153. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71181-2_8. ISBN 978-3-319-71181-2.

- Rajitha Gunaratne, GD; Khan, R; Fick, D; Robertson, B; Dahotre, N; Ironside, C (January 2017). "A review of the physiological and histological effects of laser osteotomy". Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology. 41 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/03091902.2016.1199743. PMID 27345105. S2CID 22296217.

- Coulson, CJ; Reid, AP; Proops, DW; Brett, PN (June 2007). "ENT challenges at the small scale". The International Journal of Medical Robotics + Computer Assisted Surgery. 3 (2): 91–6. doi:10.1002/rcs.132. PMID 17619240. S2CID 23907940.

- Darzi, Ara (27 October 2017). "The cheap innovations the NHS could take from sub-Saharan Africa". The Guardian.

- "DeWalt DCD790/DCD795 Instruction Manual" (PDF). DeWalt. p. 14. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Drill. |

- Nonfatal Occupational Injuries Involving the Eyes - From US Department of Labor (Accessed 29 April 2007)

- NIOSH Power Tools Sound and Vibrations Database