Ergocalciferol

Ergocalciferol, also known as vitamin D2 and nonspecifically calciferol, is a type of vitamin D found in food and used as a dietary supplement.[1] As a supplement it is used to prevent and treat vitamin D deficiency.[2] This includes vitamin D deficiency due to poor absorption by the intestines or liver disease.[3] It may also be used for low blood calcium due to hypoparathyroidism.[3] It is used by mouth or injection into a muscle.[2][3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Drisdol, Calcidol, others |

| Other names | viosterol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a616042 |

| License data | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.014 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

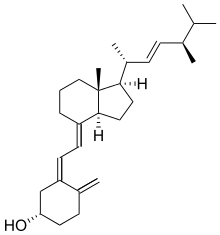

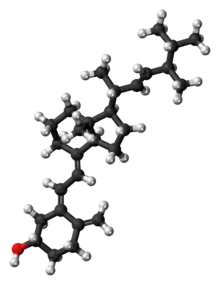

| Formula | C28H44O |

| Molar mass | 396.659 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 114 to 118 °C (237 to 244 °F) |

| |

| |

Excessive doses can result in increased urine production, high blood pressure, kidney stones, kidney failure, weakness, and constipation.[4] If high doses are taken for a long period of time, tissue calcification may occur.[3] Normal doses are safe in pregnancy.[5] It works by increasing the amount of calcium absorbed by the intestines and kidneys.[4] Food in which it is found include some mushrooms.[6]

Ergocalciferol was first described in 1936.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8] Ergocalciferol is available as a generic medication and over the counter.[4] In 2017, it was the 55th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 14 million prescriptions.[9][10] Certain foods such as breakfast cereal and margarine have ergocalciferol added to them in some countries.[11][12]

Use

Ergocalciferol may be used as a vitamin D supplement, whereas cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) is produced naturally by the skin when exposed to ultraviolet light.[13] Ergocalciferol (D2) and cholecalciferol (D3) are considered to be equivalent for vitamin D production, as both forms appear to have similar efficacy in ameliorating rickets[14] and reducing the incidence of falls in elderly patients.[15] Conflicting reports exist, however, concerning the relative effectiveness, with some studies suggesting that ergocalciferol has less efficacy based on limitations in absorption, binding, and inactivation.[16] A meta-analysis concluded that evidence usually favors cholecalciferol in raising vitamin D levels in blood, although it stated more research is needed.[16]

Mechanism

Ergocalciferol is a secosteroid formed by a photochemical bond breaking of a steroid, specifically, by the action of ultraviolet light (UV-B or UV-C) on ergosterol, a form of provitamin D2.[17]

Like cholecalciferol, Ergocalciferol is inactive by itself. It requires two hydroxylations to become active: the first in the liver by CYP2R1 to form 25-hydroxyergocalciferol (ercalcidiol or 25-OH D2[18]), and the second in the kidney by CYP27B1, to form the active 1,25-dihydroxyergocalciferol (ercalcitriol or 1,25-(OH)2D2), which activates the vitamin D receptor.[19] Unlike cholecalciferol, 25-hydroxylation is not performed by CYP27A1 for ergocalciferol.[20]

Ergocalciferol and metabolites have lower affinity to the vitamin D-binding protein compared to the D3 counterparts. The binding affinity of ercalcitriol to the vitamin D receptor is similar to that of calcitriol.[20] Ergocalciferol itself and metabolites can be deactivated by 24-hydroxylation.[21]

Sources

Fungus, from USDA nutrient database (per 100g), D2 + D3:[22][23]

- Agaricus bisporus:

- raw portobello: 0.3 μg (10 IU); exposed to ultraviolet light: 11.2 µg (446 IU)

- raw crimini: 0.1 μg (3 IU); exposed to ultraviolet light: 31.9 µg (1276 IU)

- Mushrooms, shiitake:

- raw: Vitamin D (D2 + D3): 0.4 μg (18 IU)

- dried: Vitamin D (D2 + D3): 3.9 μg (154 IU)

Lichen

- Cladina arbuscula specimens grown under different natural conditions contain provitamin D2 and vitamin D2, ranges 89-146 and 0.22-0.55 μg/g dry matter respectively. They also contain vitamin D3 (range 0.67 to 2.04 μg/g) although provitamin D3 could not be detected. Vitamin D levels correlate positively with UV irradiation.[24]

Plantae

- Alfalfa (Medicago sativa subsp. sativa), shoot: 4.8 μg (192 IU) vitamin D2, 0.1 μg (4 IU) vitamin D3[25]

Biosynthesis

The vitamin D2 content in mushrooms and C. arbuscula increase with exposure to ultraviolet light.[26][27] Ergosterol (provitamin D2) found in these fungi is converted to previtamin D2 on UV exposure, which then turns into vitamin D2. As cultured mushrooms are generally grown in darkness, less vitamin D2 is found compared to those grown in the wild or dried in the sun.[17]

When fresh mushrooms or dried powders are purposely exposed to ultraviolet light, vitamin D2 levels can be concentrated to much higher levels.[28][29][30] The irradiation procedure does not cause significant discoloration, or whitening, of mushrooms.[31] Claims have been made that a normal serving (approx. 2 oz or 60 grams) of fresh mushrooms treated with ultraviolet light have increased vitamin D content to levels up to 80 micrograms or 3200 IU if exposed to just 5 minutes of UV light after being harvested.[29]

Button mushrooms with enhanced vitamin D2 content produced this way functions similarly to a vitamin D2 supplement; both effectively improves vitamin D status.[28][32] Vitamin D2 from UV-irradiated yeast baked into bread or mushrooms is bioavailable and increases blood levels of 25(OH)D.[28]

Names

Viosterol, the name given to early preparations of irradiated ergosterol, is essentially synonymous with ergocalciferol.[33][34]

Ergocalciferol is manufactured and marketed under various names, including Deltalin (Eli Lilly and Company), Drisdol (Sanofi-Synthelabo) and Calcidol (Patrin Pharma).

References

- Coulston AM, Boushey C, Ferruzzi M (2013). Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease. Academic Press. p. 818. ISBN 9780123918840. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. pp. 703–704. ISBN 9780857111562.

- World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. p. 498. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- "Ergocalciferol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Hamilton R (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 227. ISBN 9781284057560.

- "Office of Dietary Supplements - Vitamin D". ods.od.nih.gov. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 451. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Ergocalciferol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Feral P, Hall L (2005). Dining with Friends: The Art of North American Vegan Cuisine. Friends of Animals/Nectar Bat Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780976915904.

- Bennett B, Sammartano R (2012). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Vegan Living (Second ed.). Penguin. p. Chapter 15. ISBN 9781615642793. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

- Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. (July 2011). "Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 96 (7): 1911–30. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-0385. PMID 21646368.

- Thacher TD, Fischer PR, Obadofin MO, Levine MA, Singh RJ, Pettifor JM (September 2010). "Comparison of metabolism of vitamins D2 and D3 in children with nutritional rickets". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 25 (9): 1988–95. doi:10.1002/jbmr.99. PMC 3153403. PMID 20499377.

- Fosnight SM, Zafirau WJ, Hazelett SE (February 2008). "Vitamin D supplementation to prevent falls in the elderly: evidence and practical considerations". Pharmacotherapy. 28 (2): 225–34. doi:10.1592/phco.28.2.225. PMID 18225968. S2CID 37034292.

- Tripkovic L, Lambert H, Hart K, Smith CP, Bucca G, Penson S, et al. (June 2012). "Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 95 (6): 1357–64. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.031070. PMC 3349454. PMID 22552031.

- Cardwell, G; Bornman, JF; James, AP; Black, LJ (13 October 2018). "A Review of Mushrooms as a Potential Source of Dietary Vitamin D." Nutrients. 10 (10): 1498. doi:10.3390/nu10101498. PMC 6213178. PMID 30322118.

- Suda T, DeLuca HF, Schnoes H, Blunt JW (April 1969). "25-hydroxyergocalciferol: a biologically active metabolite of vitamin D2". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 35 (2): 182–5. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(69)90264-2. PMID 5305760.

- "IUPAC-IUB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature (JCBN): Nomenclature of vitamin D. Recommendations 1981". European Journal of Biochemistry. 124 (2): 223–7. May 1982. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06581.x. PMID 7094913.

- Bikle DD (March 2014). "Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications". Chemistry & Biology. 21 (3): 319–29. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. PMC 3968073. PMID 24529992.

- Houghton LA, Vieth R (October 2006). "The case against ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) as a vitamin supplement". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 84 (4): 694–7. doi:10.1093/ajcn/84.4.694. PMID 17023693.

- "USDA nutrient database – use the keyword 'portabello' and then click submit". Archived from the original on 22 February 2015.

- Haytowitz DB (2009). "Vitamin D in mushrooms" (PDF). Nutrient Data Laboratory, US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Wang T, Bengtsson G, Kärnefelt I, Björn LO (September 2001). "Provitamins and vitamins D₂and D₃in Cladina spp. over a latitudinal gradient: possible correlation with UV levels". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. B, Biology. 62 (1–2): 118–22. doi:10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00160-9. PMID 11693362.

- "Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases". Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- Wang T, Bengtsson G, Kärnefelt I, Björn LO (September 2001). "Provitamins and vitamins D₂ and D₃ in Cladina spp. over a latitudinal gradient: possible correlation with UV levels". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology. B, Biology. 62 (1–2): 118–22. doi:10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00160-9. PMID 11693362.

- Haytowitz DB (2009). "Vitamin D in mushrooms" (PDF). Nutrient Data Laboratory, US Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Keegan RJ, Lu Z, Bogusz JM, Williams JE, Holick MF (January 2013). "Photobiology of vitamin D in mushrooms and its bioavailability in humans". Dermato-Endocrinology. 5 (1): 165–76. doi:10.4161/derm.23321. PMC 3897585. PMID 24494050.

- "Bringing Mushrooms Out of the Dark". NBC News. 18 April 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- Simon RR, Borzelleca JF, DeLuca HF, Weaver CM (June 2013). "Safety assessment of the post-harvest treatment of button mushrooms (Agaricus bisporus) using ultraviolet light". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 56: 278–89. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2013.02.009. PMID 23485617.

- Koyyalamudi SR, Jeong SC, Song CH, Cho KY, Pang G (April 2009). "Vitamin D2 formation and bioavailability from Agaricus bisporus button mushrooms treated with ultraviolet irradiation". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (8): 3351–5. doi:10.1021/jf803908q. PMID 19281276.

- Urbain P, Singler F, Ihorst G, Biesalski HK, Bertz H (August 2011). "Bioavailability of vitamin D₂ from UV-B-irradiated button mushrooms in healthy adults deficient in serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D: a randomized controlled trial". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 65 (8): 965–71. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2011.53. PMID 21540874.

- Science Service (1930). "Viosterol official name for irradiated ergosterol". Journal of Chemical Education. 7 (1): 166. Bibcode:1930JChEd...7..166S. doi:10.1021/ed007p166.

- See "Viosterol" and "Calciferol" at Merriam-Webster Medical Dictionary, e.g., "Medical Definition of VIOSTEROL". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014. and "Definition of CALCIFEROL". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014., accessed 10 July 2014.

External links

- "Ergocalciferol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- NIST Chemistry WebBook page for ergocalciferol