French language in Canada

French is the mother tongue of approximately 7.2 million Canadians (20.6 per cent of the Canadian population, second to English at 56 per cent) according to the 2016 Canadian Census.[1] Most Canadian native speakers of French live in Quebec, the only province where French is the majority and sole-official language.[2] 77 percent of Quebec's population are native francophones, and 95 percent of the population speak French as their first or second language.[3]

Additionally, about one million native francophones live in other provinces, forming a sizable minority in New Brunswick, which is officially a bilingual province; approximately one-third of New Brunswick's population is francophone. There are also French-speaking communities in Manitoba and Ontario, where francophones make up approximately 4 percent of the population,[4] as well as significantly smaller communities in Alberta, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan – approximately 1 to 2 percent.[4] Many of these communities are, in the contemporary era, supported by French-language institutions. In 2016, 29.8 percent of Canadians reported being able to conduct a conversation in French.

By the 1969 Official Languages Act, both English and French are recognized as official languages in Canada and granted equal status by the Canadian government.[5] While French, with no specification as to dialect or variety, has the status of one of Canada's two official languages at the federal government level, English is the native language of the majority of Canadians. The federal government provides services and operates in both languages.

The provincial governments of Ontario, New Brunswick and Manitoba are required to provide services in French where justified by the number of francophones. French is also an official language of all three Canadian territories: the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon. Whatever that status of the French or English languages in a province or territory, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms requires all provinces and territories to provide primary and secondary education to their official-language minorities.

History and evolution

16th century

In 1524, the Florentine navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano, working for Italian bankers in France, explored the American coast from Florida to Cape Breton. In 1529, Verrazzano mapped a part of the coastal region of the North American continent under the name Nova Gallia (New France). In 1534, King Francis I of France sent Jacques Cartier to explore previously unfamiliar lands. Cartier found the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, sealed an alliance with the local people and obtained passage to go farther. During his second expedition (1535–1536), Cartier came upon the Saint Lawrence River, a path into the heart of the continent. However, Cartier failed to establish a permanent colony in the area, and war in Europe kept France from further colonization through the end of the 16th century.[6][7]

17th century

At the beginning of the 17th century, French settlements and private companies were established in the area that is now eastern Canada. In 1605, Samuel de Champlain founded Port Royal (Acadia), and in 1608 he founded Quebec City. In 1642, the foundation of Ville Marie, the settlement that would eventually become Montreal, completed the occupation of the territory.

In 1634, Quebec contained 200 settlers who were principally involved in the fur trade. The trade was profit-making and the city was on the point of becoming more than a mere temporary trading post.

In 1635, Jesuits founded the secondary school of Quebec for the education of children. In 1645, the Compagnie des Habitants was created, uniting the political and economic leaders of the colony. French was the language of all the non-native people.

In 1685, the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV (1654–1715), which had legalized freedom of religion of the Reformed Church, caused the emigration from France of 300,000 Huguenots (French Calvinists) to other countries of Europe and to North America.[8]

18th century

With the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, the British began their domination of eastern North America, some parts of which had been controlled by the French. The British took mainland Nova Scotia in 1713. Present-day Maine fell to the British during Father Rale's War, while present-day New Brunswick fell after Father Le Loutre's War. In 1755 the majority of the French-speaking inhabitants of Nova Scotia were deported to the Thirteen Colonies. After 1758, they were deported to England and France. The Treaty of Paris (1763) completed the British takeover, removing France from Canadian territory, except for Saint Pierre and Miquelon at the entrance of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence.

The French language was relegated to second rank as far as trade and state communications were concerned. Out of necessity, the educated class learned the English language and became progressively bilingual, but the great majority of the French-speaking inhabitants continued to speak only French, and their population increased. Anglicization of the French population failed, and it became obvious that coexistence was required. In 1774, Parliament passed the Quebec Act, restoring French civil laws and abrogating the Test Act, which had been used to suppress Catholicism.[9]

Canada as a federal state

In 1791, Parliament repealed the Quebec Act and gave the king authority to divide the Canadian colony into two new provinces: Upper Canada, which later became Ontario, and Lower Canada, which became Quebec.

In 1867, three colonies of British North America agreed to form a federal state, which was named Canada. It was composed of four provinces:

- Ontario, formerly Upper Canada

- Quebec, formerly Lower Canada

- Nova Scotia

- New Brunswick, former Acadian territory

In Quebec, French became again the official language; until then it was the vernacular language but with no legal status.[10][11][12]

Dialects and varieties

As a consequence of geographical seclusion and as a result of British conquest, the French language in Canada presents three different but related main dialects. They share certain features that distinguish them from European French.

All of these dialects mix, to varying degrees, elements from regional languages and folk dialects spoken in France at the time of colonization. For instance, the origins of Quebec French lie in 17th- and 18th-century Parisian French, influenced by folk dialects of the early modern period and other regional languages (such as Norman, Picard and Poitevin-Saintongeais) that French colonists had brought to New France. It has been asserted that the influence of these dialects has been stronger on Acadian French than on French spoken in Quebec. The three dialects can also be historically and geographically associated with three of the five former colonies of New France: Canada, Acadia and Terre-Neuve (Newfoundland).

In addition, there is a mixed language known as Michif, which is based on Cree and French. It is spoken by Métis communities in Manitoba and Saskatchewan as well as within adjacent areas of the United States.

Immigration after World War II has brought francophone immigrants from around the world, and with them other French dialects.

Francophones across Canada

Quebec

Quebec is the only province whose sole official language is French. Today, 81.4 percent of Quebecers are first language francophones.[14] About 95 percent of Quebecers speak French.[3] However, many of the services the provincial government provides are available in English for the sizeable anglophone population of the province (notably in Montreal). For native French speakers, Quebec French is noticeably different in pronunciation and vocabulary from the French of France, sometimes called Metropolitan French, but they are easily mutually intelligible in their formal varieties, and after moderate exposure, in most of their informal ones as well. The differences are primarily due to changes that have occurred in Quebec French and Parisian French since the 18th century, when Britain gained possession of Canada.

Different regions of Quebec have their own varieties: Gaspé Peninsula, Côte-Nord, Quebec City, Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean, Outaouais, and Abitibi-Témiscamingue have differences in pronunciation as well as in vocabulary. For example, depending on one's region, the ordinary word for "kettle" can be bouilloire, bombe, or canard.

In Quebec, the French language is of paramount importance. For example, the stop signs on the roads are written ARRÊT (which has the literal meaning of "stop" in French), even if other French-speaking countries, like France, use STOP. On a similar note, movies originally made in other languages than French (mostly movies originally made in English) are more literally named in Quebec than they are in France (e.g. The movie The Love Guru is called Love Gourou in France, but in Quebec it is called Le Gourou de l'amour).

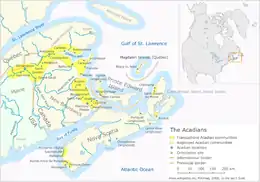

Atlantic Canada

The colonists living in what are now the provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia were principally constituted of Bretons, Normans, and Basques. Conquered by the English, they suffered massive deportations to the United States and France. Others went into exile to Canada or to nearby islands. Those who stayed were persecuted. At the end of the 18th century, more liberal measures granted new lands to those who had stayed, and measures were taken to promote the return of numerous exiled people from Canada and Miquelon. The number of Acadians rose rapidly, to the point of gaining representation in the Legislative Assembly.

French is one of the official languages, with English, of the province of New Brunswick. Apart from Quebec, this is the only other Canadian province that recognizes French as an official language. Approximately one-third of New Brunswickers are francophone,[14] by far the largest Acadian population in Canada.

The Acadian community is concentrated in primarily rural areas along the border with Quebec and the eastern coast of the province. Francophones in the Madawaska area may also be identified as Brayon, although sociologists have disputed whether the Brayons represent a distinct francophone community, a subgroup of the Acadians or an extraprovincial community of Québécois. The only major Acadian population centre is Moncton, home to the main campus of the Université de Moncton. Francophones are, however, in the minority in Moncton.

In addition to New Brunswick, Acadian French has speakers in portions of mainland Quebec and in the Atlantic provinces of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland. In these provinces, the percentage of francophones is much smaller than in New Brunswick. In some communities, French is an endangered language.

Linguists do not agree about the origin of Acadian French. Acadian French is influenced by the langues d'oïl. The dialect contains, among other features, the alveolar r and the pronunciation of the final syllable in the plural form of the verb in the third person. Acadia is the only place outside Jersey (a Channel Island close to mainland Normandy) where Jèrriais speakers can be found.[15]

Ontario

Although French is the native language of just over half a million Canadians in Ontario, francophone Ontarians represent only 4.7 per cent of the province's population. They are concentrated primarily in the Eastern Ontario and Northeastern Ontario regions, near the border with Quebec, although they are also present in smaller numbers throughout the province. Francophone Ontarians form part of a larger cultural group known as Franco-Ontarians, of whom only 60 per cent still speak the language at home. The city of Ottawa counts the greatest number of Franco-Ontarians in the province. Franco-Ontarians are originally from a first wave of immigration from France, from a second wave from Quebec. The third wave comes from Quebec, but also from Haiti, Morocco, Africa, etc.

The province has no official language defined in law, although it is a largely English-speaking province. Ontario law requires that the provincial Legislative Assembly operate in both English and French (individuals can speak in the Assembly in the official language of their choice), and requires that all provincial statutes and bills be made available in both English and French. Furthermore, under the French Language Services Act, individuals are entitled to communicate with the head or central office of any provincial government department or agency in French, as well as to receive all government services in French in 25 designated areas in the province, selected according to minority population criteria. The provincial government of Ontario's website is bilingual. Residents of Ottawa, Toronto, Windsor, Sudbury and Timmins can receive services from their municipal government in the official language of their choice.

There are also several French-speaking communities on military bases in Ontario, such as the one at CFB Trenton. These communities have been founded by francophone Canadians in the Canadian Forces who live together in military residences.[16][17]

The term Franco-Ontarian accepts two interpretations. According to the first one, it includes all French speakers of Ontario, wherever they come from. According to second one, it includes all French Canadians born in Ontario, whatever their level of French is.[18] The use of French among Franco-Ontarians is in decline due to the omnipresence of the English language in a lot of fields.

Newfoundland

The island was discovered by European powers by John Cabot in 1497. Newfoundland was annexed by England in 1583. It is the first British possession in North America.

In 1610, the Frenchmen became established in the peninsula of Avalon and went to war against the Englishmen. In 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht acknowledged the sovereignty of the Englishmen.

The origin of Franco-Newfoundlanders is double: the first ones to arrive are especially of Breton origin, attracted by the fishing possibilities. Then, from the 19th century, the Acadians who came from the Cape Breton Island and from the Magdalen Islands, an archipelago of nine small islands belonging to Quebec, become established.

Up to the middle of the 20th century, Breton fishers, who had Breton as their mother tongue, but who had been educated in French came to settle. This Breton presence can explain differences between the Newfoundland French and the Acadian French.

In the 1970s, the French language appears in the school of Cape St. George in the form of a bilingual education. In the 1980s, classes of French for native French speakers are organized there.[6][19]

Western Canada

Manitoba also has a significant Franco-Manitoban community, centred especially in the St. Boniface area of Winnipeg, but also in numerous surrounding towns. The provincial government of Manitoba boasts the only bilingual website of the Prairies; the Canadian constitution makes French an official language in Manitoba for the legislature and courts. Saskatchewan also has a Fransaskois community, as does Alberta with its Franco-Albertans, and British Columbia hosts the Franco-Columbians.

Michif, a dialect of French originating in Western Canada, is a unique mixed language derived from Cree and French. It is spoken by a small number of Métis living mostly in Manitoba and in North Dakota.

Northern Canada

French is an official language in each of the three northern territories: the Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and Nunavut. Francophones in the Yukon are called Franco-Yukonnais, those from the Northwest Territories, Franco-Ténois (from the French acronym for the Northwest Territories, T.N.-O.), and those in Nunavut, Franco-Nunavois.

French-speaking communities in Canada outside of Quebec

- Franco-Ontarians (or Ontarois)

- Acadians (in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island; also present in portions of Quebec and Newfoundland)

- Franco-Manitobans

- Fransaskois (in Saskatchewan)

- Franco-Albertans

- Franco-Columbians

- Franco-Terreneuviens

- Franco-Ténois (in the Northwest Territories)

- Franco-Yukon(n)ais (in the Yukon)

- Franco-Nunavois (in Nunavut)

See also

- Office québécois de la langue française

- Charter of the French Language

- Canadian French

- Quebec French

- Official bilingualism in Canada

- Québécois

- Joual

- Chiac

- Quebec French lexicon

- French Canadian

- Languages of Canada

- Acadian French

- Metis French

- Influence of French on English

- French language in the United States

- French language

- French phonology

- Michif language

- American French (disambiguation)

Notes

- Canada, Government of Canada, Statistics. "Census Profile, 2016 Census – Canada [Country] and Canada [Country]". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- OLF Archived 22 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Census Profile, 2016 Census". Statistics Canada. 2 August 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Population by language spoken most often at home and age groups, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories – 20% sample data". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Official Languages Act – 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.)". Act current to July 11th, 2010. Department of Justice. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- Atlas Universalis (1996), Tome 2, p. 57

- Atlas Universalis (1996), Tome 5, p. 23

- Atlas Universalis (1996) Tome 4, pp. 837–838

- Atlas Universalis (1996) Tome 4, pp. 838–839

- Atlas Universalis (1996) Tome 4, pp. 840–842

- Atlas Universalis (1996) Tome 19, pp. 397–404

- Bourhis, Richard Y.; Lepicq, Dominique (1993). "Québécois French and language issues in Québec". In Posner, Rebecca; Green, John N. (eds.). Trends in Romance Linguistics and Philology. Volume 5: Bilingualism and Linguistic Conflict in Romance. New York: Mouton De Gruyter. ISBN 311011724X.

- "Francophones of Nunavut (Franco-Nunavois)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Profile of languages in Canada: Provinces and territories. Retrieved 3 May 2011.

- Atlas Universalis (1996), Thésaurus A-C, p. 24

- Statistiques Canada. "Population dont le français est la langue parlée le plus souvent à la maison, Canada, Provinces, territoires et Canada moins le Québec, 1996 à 2006". Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- David Block; Heller Monica (2002). Globalization and language teaching. Taylor and Francis Group.

- Atlas Universalis (1996), Thésaurus K-M, p. 2638

- Atlas Universalis (1996), Tome 4, pp. 840–842