Goa Inquisition

The Goa Inquisition (Portuguese: Inquisição de Goa) was an extension of the Portuguese Inquisition in colonial-era Portuguese India. The Inquisition was established by the colonial era Inquisition in Portuguese India to enforce Catholic orthodoxy in the Indian colonies of the Portuguese Empire,[1] and to counter the New Christians, who were accused of "crypto-Hinduism", and the Old Christian Nasranis, accused of "Judaising".[1] It was established in 1560, briefly suppressed from 1774 to 1778, continued thereafter until finally abolished in 1812.[2][3] The Inquisition punished those who had converted to Catholicism but were suspected by Jesuit clergy of practising their previous religion in secret. Predominantly, those targeted were accused of Crypto-Hinduism.[4][5][6] Many criminally-charged natives were imprisoned, publicly flogged and, dependent on the criminal charge, sentenced to death.[7][8] The Inquisitors also seized and burnt any books written in Sanskrit, Dutch, English, or Konkani, on the suspicions that they contain deviationist or Protestant material.[9]

Holy Office of the Portuguese Inquisition in Goa Inquisição de Goa Goa Inquisition | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Seal of the Portuguese Inquisition in Goa. | |

| Type | |

| Type | Part of the Portuguese Inquisition |

| History | |

| Established | 1560 |

| Disbanded | 1812 |

| Meeting place | |

| Portuguese India | |

While some sources claim the Goa Inquisition was requested by Jesuit missionary Francis Xavier (from his headquarters Malacca in a letter dated 16 May 1546 to King John III of Portugal[7][10]), the only letter that asked for a king's minister, with special powers to protect the newly converted Christians from the Portuguese commandants, was the one dated 20 January 1545.[11] Between the Inquisition's beginning in 1561 and its temporary abolition in 1774, around 16,000 persons were charged before the Inquisition. Almost all of the Goa Inquisition's records were burnt by the Portuguese when the inquisition was abolished in 1812.[5] It is impossible to know the exact number of those put on trial and the punishments they were prescribed.[4] The few records that have survived suggest that at least 57 were executed for their religious crime, and another 64 were burned in effigy because they had already died in jail before sentencing.[12][13]

In Goa, the Inquisition also prosecuted violators of prohibitions against the observance of Hindu or Muslim rites or festivals, or interfered with Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians to Catholicism.[4] The Inquisition was the judicial system over Indian Catholics, Hindus and of Portuguese settlers from Europe (mostly New Christians and Jews). The Inquisition laws made reconversion to Hinduism, Islam and Judaism and the use of the indigenous Konkani Language a criminal offense.[7] The inquisition was also a method of confiscating property and enriching the Inquisitors.[14] Although the Goa Inquisition ended in 1812, the religious discrimination and persecution of Indian Hindus and Muslims by the Portuguese Christian Government continued in other forms such as the Xenddi Tax, which was similar to the Jaziya Tax.[15][16][17]

Background

The Inquisition in Portugal

Ferdinand and Isabella were married in 1469 thereby uniting the Iberian kingdoms of Aragon and Castile into Spain.[18][19] In 1492, they expelled the Jews, many of whom then moved to Portugal.[20] Within five years, the anti-Judaism and inquisition ideas were adopted in Portugal.[18][19] Instead of another expulsion, the King of Portugal ordered the forced conversion of the Jews in 1497, and these were called New Christians or Crypto-Jews.[20] He stipulated that the validity of their conversions would not be investigated for two decades.[21] In 1506 in Lisbon, there was a massacre of several hundred 'Conversos' or 'Marranos', as newly converted Jews or New Christians were called, instigated by the preaching of two Spanish Dominicans. Some persecuted Jews fled Portugal for the New World in the Americas.[21][1] Others went to Asia as traders, settling in India.[21]

These ideas and the practice of Inquisition on behalf of the Holy Office of Catholic Church was spread by the Jesuits and colonial administrators of Portugal to Portuguese colonies such as Estado da India.[1][22] One of the most notable New Christians was professor Garcia de Orta, who emigrated to Goa in 1534. He was posthumously convicted of Judaism.[21] The Goa Inquisition institution enforced by the Portuguese Christians was not unusual, as similar institutions operated in South American colonies during the same centuries such as the Lima Inquisition and the Brasil Inquisition under the Lisbon tribunal. Like the Goan inquisition, these parallel tribunals accused and arrested suspects, deployed torture, extracted forced confessions, convicted and issued punishments for secretly practicing religious beliefs different than Christianity.[23][20]

Portuguese arrival and conquest

Goa was founded and built by ancient Hindu kingdoms and had served as a capital of the Kadamba dynasty. In late 13th-century, a Muslim invasion led to the plunder of Goa by Malik Kafur on behalf of Alauddin Khilji and an Islamic occupation.[24] In the 14th-century, Vijayanagara Hindu rulers conquered and occupied it.[24] It became a part of Bahmani Sultanate in the 15th century, thereafter was under the rule of Sultan Adil Shah of Bijapur when Vasco da Gama reached Kozhekode (Calicut), India in 1498.[24]

After da Gama's return, Portugal sent an armed fleet to conquer and create a colony in India. In 1510, the Portuguese Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque (c. 1453-1515) launched a series of campaigns to take Goa, wherein the Portuguese ultimately prevailed.[24] The Christian Portuguese were assisted by the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire's regional agent Timmayya in their attempt to capture Goa from the Muslim ruler Adil Shah.[25] Timmaya's ideas so impressed the early Portuguese that they called him the "a messenger of the Holy Spirit" and not a gentio.[26][27] Goa became the center of Portuguese colonial possessions in India and activities in other parts of Asia. It also served as the key and lucrative trading center between the Portuguese and the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire and Muslim Bijapur Sultanate to its east. Wars continued between the Bijapur Sultanate and the Portuguese forces for decades.[24]

Introduction of the Inquisition to India

After da Gama returned to Portugal from his maiden voyage to India, Pope Nicholas V issued the Papal bull Romanus Pontifex. This granted a padroado from the Holy See, giving Portugal the responsibility, monopoly right and patronage for the propagation of the Catholic Christian faith in newly discovered areas, along with exclusive rights to trade in Asia on behalf of the Roman Catholic Empire.[28][29][30] From 1515 onwards, Goa served as the center of missionary efforts under Portugal's royal patronage (Padroado) to expand Catholic Christianity in Asia.[29][note 1] Similar padroados were also issued by the Vatican in the favor of Spain and Portugal in South America in the 16th-century. The padroado mandated the building of churches and support for Catholic missions and proselytization activities in the new lands, and brought these under the religious jurisdiction of the Vatican. The Jesuits were the most active of the religious orders in Europe that participated under the padroado mandate in the 16th and 17th-centuries.[33][note 2]

The establishment of the Portuguese on the Western coast of India was of particular interest to the New Christians population of Portugal who were suffering harshly under the Portuguese Inquisition. The Jewish New Christian targets of the Inquisition in Portugal began flocking to Goa, and their community reached considerable proportions. India was attractive for Jews who had been forcibly baptized in Portugal for a variety of reasons. One reason was that India was home to ancient, well-established Jewish communities. Jews who had been forcibly converted could approach these communities, and re-join their former faith if they chose to do so, without having to fear for their lives as these areas were beyond the scope of the Inquisition.[35] Another reason was the opportunity to engage in trade (spices, diamonds, etc) from which New Christians in Portugal had been restricted at the onset of the Portuguese Inquisition. In his book, The Marrano Factory, Professor Antonio Saraiva of the University of Lisbon details the strength of the New Christians on the economic front by quoting a 1613 document written by attorney, Martin de Zellorigo. Zellorigo writes regarding "the Men of the Nation" (a term used for Jewish New Christians): "For in all of Portugal there is not a single merchant (hombre de negocios) who is not of this Nation. These people have their correspondents in all lands and domains of the king our lord. Those of Lisbon send kinsmen to the East Indies to establish trading-posts where they receive the exports from Portugal, which they barter for merchandise in demand back home. They have outposts in the Indian port cities of Goa and Cochin and in the interior. In Lisbon and in India nobody can handle the trade in merchandise except persons of this Nation. Without them, His Majesty will no longer be able to make a go of his Indian possessions, and will lose the 600,000 ducats a year in duties which finance the whole enterprise — from equipping the ships to paying the seamen and soldiers"[36] The Portuguese reaction to the New Christians in India came in the form of bitter letters of complaint and polemics that were written, and sent to Portugal by secular and ecclesiastical authorities; these complaints were about trade practices, and the abandonment of Catholicism.[37] In particular, the first archbishop of Goa Dom Gaspar de Leao Pereira and, later Francis Xavier, were extremely critical of the New Christian presence, and were highly influential in petitioning for the establishment of the Inquisition in Goa.

Portugal also sent missionaries to Goa, and its colonial government supported the Christian mission with incentives for baptizing Hindus and Muslims into Christians.[38] A diocese was established in Goa in 1534.[29] In 1542, Martin Alfonso was appointed the new administrator of Asian colonies of Portugal. He arrived in Goa with Francis Xavier, an influential figure in the history of Goa Inquisition.[24] He had co-founded the Jesuit order, the main source of missionaries who implemented the Inquisition. Further, in a letter dated 16 May 1546 to King John III of Portugal, he pleaded the King to start Inquisition in Goa.[7] His recommendation for an Inquisition contrasted with his earlier writings in 1543 where he highly praised Goa. By 1548, the Portuguese colonists had launched fourteen churches in the colony.[39]

The surviving records of missionaries from 16th to 17th century, states Délio de Mendonça, extensively stereotypes and criticizes the gentiles, a term that broadly referred to Jews, Hindus and Muslims.[40] The Portuguese were regularly deploying their military power and engaging in war both in Goa and Cochin. The violence triggered hostility from the ruling classes, traders and the peasants. To Portuguese missionaries, the Gentiles of India that were not outright hostile were superstitious, weak and greedy.[40] Their records state that Indians converted to Christianity for economic gains offered by the missionaries such as jobs or clothing gifts. After baptism, these new converts continued to practice their old religion in secret in the manner similar to Crypto-Jews who had been forcibly converted to Christianity in Portugal earlier. Jesuit missionaries considered this a threat to the purity of Catholic Christian belief and pressed for Inquisition in order to punish the Crypto-Hindus, Crypto-Muslims and Crypto-Jews, thereby ending the heresy.[40] The letter from Francis Xavier asking the King to start the Goan Inquisition received a favorable response in 1560, eight years after Xavier's death.[7]

The Goa Inquisition adapted the directives issued between 1545 and 1563 by the Council of Trent to Goa and other Indian colonies of Portugal. This included attacking local customs, active proselytization to increase the number of Christian converts, fighting enemies of Catholic Christians, uprooting behaviors that were deemed to be heresies and maintaining the purity of Catholic faith.[41] The Portuguese accepted the caste system thereby attracting the elites of the local society, states Mendonça, because Europeans of the sixteenth century had their estate system and held that social divisions and hereditary royalty were divinely established. It was the festivals, syncretic religious practices and other traditional customs that were identified as heresy, relapses and shortcomings of the natives needing a preventative and punitive Inquisition.[41]

Launch of the Inquisition in India

The practice of trying and punishing people for religious crimes in Goa, and targeting Judaizing, before the Inquisition was launched. A Portuguese order to destroy Hindu temples along with the seizure of Hindu temple properties and their transfer to the Catholic missionaries is dated 30 June 1541.[42]

Prior to authorizing of the Inquisition office in Goa in 1560, King John III of Portugal issued an order, on March 8, 1546, to forbid Hinduism, destroy Hindu temples, prohibit the public celebration of Hindu feasts, expel Hindu priests and severely punish those who created any Hindu images in Portuguese possessions in India.[43] A special religious tax was imposed before 1550 on Muslim mosques within Portuguese territory. Records suggest that a New Christian was executed by the Portuguese in 1539 for the religious crime of "heretical utterances". A Jewish converso or Christian convert named Jeronimo Dias was garroted and burnt at the stake in Goa by the Portuguese, for the "crime" of Judaizing as early as 1543 for heresy before the Goa Inquisition tribunal was formed.[44][43]

The beginning of the Inquisition

Cardinal Henrique of Portugal sent Aleixo Díaz Falcão as the first inquisitor.[45] He established the first tribunal which, states Henry Lea, became the most pitiless force of persecution in Portuguese colonial empire.[45] The Goa Inquisition office was housed in the former palace of Sultan Adil Shah.[46]

The inquisitor's first act was to forbid any open practice of the Hindu faith on pain of death. Other restrictions imposed by the Goa Inquisition included:[47]

- Hindus were forbidden from occupying any public office, and only a Christian could hold such an office;[47][48]

- Hindus were forbidden from producing any Christian devotional objects or symbols;[47]

- Hindu children whose father had died were required to be handed over to the Jesuits for conversion to Christianity;[47] This began under a 1559 royal order from Portugal, whereafter Hindu children alleged to be orphan were seized by the Jesuits and converted to Christianity.[48] This law was enforced on children even if mother was still alive, in some cases even if the father was alive. The parental property was also seized when the Hindu child was seized. In some cases, states Lauren Benton, the Portuguese authorities extorted money for the "return of the orphans".[48]

- Hindu women who converted to Christianity could inherit all of the property of their parents;[47]

- Hindu clerks in all village councils were replaced with Christians;[47]

- Christian ganvkars could make village decisions without any Hindu ganvkars present, however Hindu ganvkars could not make any village decisions unless all Christian canvas were present; in Goan villages with Christian majorities, Hindus were forbidden from attending village assemblies.[48]

- Christian members were to sign first on any proceedings, Hindus later;[49]

- In legal proceedings, Hindus were unacceptable as witnesses, only statements from Christian witnesses were admissible.[48]

- Hindu temples were demolished in Portuguese Goa, and Hindus were forbidden from building new temples or repairing old ones. A temple demolition squad of Jesuits was formed which actively demolished pre-16th century temples, with a 1569 royal letter recording that all Hindu temples in Portuguese colonies in India have been demolished and burnt down (desfeitos e queimados);[49]

- Hindu priests were forbidden from entering Portuguese Goa to officiate Hindu weddings.[49]

Sephardic Jews living in Goa, many of whom had fled the Iberian Peninsula to escape the excesses of the Spanish Inquisition, were also persecuted in case they, or their ancestors, had fraudulently converted to Christianity.[46] The narrative of Da Fonseca describes the violence and brutality of the inquisition. The records speak of the demand for hundreds of prison cells to accommodate the accused.[46]

From 1560 to 1774, a total of 16,172 persons were tried by the tribunals of the Inquisition.[50] While it also included individuals of different nationalities, the overwhelming majority, nearly three quarters, were natives, almost equally represented by Catholics and non-Christians. Many of these were hauled up for crossing the border and cultivating lands there.[51]

According to Benton, between 1561 and 1623, the Goa Inquisition brought 3,800 cases. This was a large number given that the total population of Goa was about 60,000 in the 1580s with an estimated Hindu population then about a third or 20,000.[52]

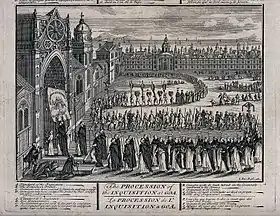

Seventy-one autos de fé ("act of faith") were recorded, the grand spectacle of public penance often followed by convicted individuals being variously punished up to and including burning at the stake. In the first few years alone, over 4000 people were arrested.[46] According to a 20th-century account, in the first hundred years, the Inquisition burnt 57 people to death at the stake and 64 in effigy, of whom 105 were men and 16 were women.[53] (The sentence of "burning in effigy" was applied to those convicted in absentia or who had died in prison; in the latter case, their remains were burned in a coffin at the same time as the effigy, which was hung up for public display.)[12] Others sentenced to various punishments totalled 4,046, of whom 3,034 were men and 1,012 were women.[53] According to the Chronista de Tissuary (Chronicles of Tiswadi), the last auto de fé was held in Goa on 7 February 1773.[53]

Implementation and consequences

An appeal to start the Inquisition in the Indian colonies of Portugal was sent by Vicar General Miguel Vaz.[55] According to Indo-Portuguese historian Teotonio R. de Souza, the original requests targeted the "Moors" (Muslims), New Christian and the Hindus, and it made Goa a center of persecution operated by the Portuguese.[56]

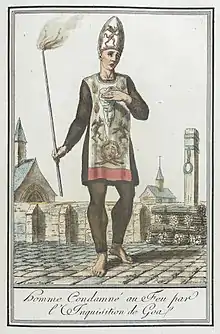

The colonial administration under demands of the Jesuits and Church Provincial Council of Goa in 1567 enacted anti-Hindu laws to end what the Catholics considered to be heretical conduct and to encourage conversions to Christianity. Laws were passed banning Christians from keeping Hindus in their employ, and the public worship of Hindus was deemed unlawful.[57][49] Hindus were forced to assemble periodically in churches to listen to the Christian doctrine or to the criticism of their religion.[49][58] Hindu books in Sanskrit, Marathi and Konkani were burnt by the Goan Inquisition.[59] It also forbade Hindu priests from entering Goa to officiate Hindu weddings.[49] Violations resulted in various forms of punishment to non-Catholics such as fines, public flogging, banishment to Mozambique, imprisonment, execution, burning at stakes or burning in effigy under the orders of the Christian Portuguese prosecutors at the auto-da-fé.[7][60][61] The arrests were arbitrary, witnesses were granted anonymity, the property of the accused was immediately confiscated, torture was deployed to extract confessions, recanting of confession was considered evidence of dishonest character, and an oath of silence of the trial process was required of those released with penalties of re-arrest if they spoke to anyone about their experiences.[62][63]

The inquisition forced Hindus to flee Goa in large numbers[52] and later the migration of its Christians and Muslims, from Goa to the surrounding regions that were not in the control of the Jesuits and Portuguese India.[49][64] The Hindus responded to the destruction of their temples by recovering the images from the ruins of their older temples and using them to build new temples just outside the borders of the Portuguese controlled territories. In some cases where the Portuguese built churches on the spot the destroyed temples were, Hindus started annual processions that carry their gods and goddesses linking their newer temples to the site where the churches stand, after Portuguese colonial era ended.[65]

Persecution of Hindus

Hindus were the primary target for persecution and punishment for their faith by the Catholic prosecutors of the Goan Inquisition. About 74% of those sentenced were charged with Crypto-Hinduism, while others targeted were non-Hindus such as 1.5% sentenced for being Crypto-Muslims, 1.5% for obstructing the operations of the Holy Office of the Inquisition.[66] Most records of the nearly 250 years of Inquisition trials were burnt by the Portuguese after the Inquisition was banned. Those that have survived, such as those between 1782-1800, state that people continued to be tried and punished, and the victims were predominantly the Hindus.[66] A larger proportion of those arrested, tried and sentenced during the Goa Inquisition, according to António José Saraiva, came from the lowest social strata.[66] The trial records suggest that the victims were not exclusively Hindus, but included members of other religions found in India as well as some Europeans.[66]

| Social group | Percent[66] |

|---|---|

| Shudras | 18.5% |

| Curumbins (Tribal-Untouchables)[67] |

17.5% |

| Chardos (Kshatriya)[68] |

7% |

| Brahmins | 5% |

Fr. Diogo da Borba and his advisor Vicar General Miguel Vaz followed the missionary goals to convert the Hindus. In cooperation with the Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries, the Portuguese administration in Goa and military were deployed to destroy the cultural and institutional roots of Hindus and other Indian religions. For example, Viceroy and Captain General António de Noronha and, later Captain General Constantino de Sa de Noronha, systematically destroyed Hindu and Buddhist temples in Portuguese possessions and during attempted new conquests on the Indian subcontinent.[69]

Exact data on the nature and number of Hindu temples destroyed by the Christian missionaries and Portuguese government are unavailable.[70] Some 160 temples were razed to the ground on the Goa island by 1566. Between 1566 and 1567, a campaign by Franciscan missionaries destroyed another 300 Hindu temples in Bardez (North Goa).[70] In Salcete (South Goa), approximately another 300 Hindu temples were destroyed by the Christian officials of the Inquisition. Numerous Hindu temples were destroyed elsewhere at Assolna and Cuncolim by Portuguese authorities.[70] A 1569 royal letter in Portuguese archives records that all Hindu temples in its colonies in India have been burnt and razed to the ground.[71]

According to Ulrich Lehner, "Goa had been a tolerant place in the sixteenth century, but the Goan Inquisition had turned it into a hostile location for Hindus and members of other Asian religions. Temples had been razed, public Hindu rituals forbidden, and conversions to Hinduism severely punished. The Goa Inquisition prosecuted harshly any cases of public Hindu worship; over three-quarters of its cases pertained to this, and only two percent to apostasy or heresy."[72]

New laws promulgated between 1566 and 1576 prohibited Hindus from repairing any damaged temples or constructing new ones.[70] Ceremonies including public Hindu weddings were banned.[61] Anyone who owned an image of a Hindu god or goddess was deemed a criminal.[70] Non-Hindus in Goa were encouraged to identify and report anyone who owned images of god or goddess to the Inquisition authorities. Those accused were searched and if any evidence was found, such "idol owning" Hindus were arrested and they lost their property. Half of the seized property went as reward to the accusers, the other half to the church.[70]

"The fathers of the Church forbade the Hindus under terrible penalties the use of their own sacred books, and prevented them from all exercise of their religion. They destroyed their temples, and so harassed and interfered with the people that they abandoned the city in large numbers, refusing to remain any longer in a place where they had no liberty, and were liable to imprisonment, torture and death if they worshipped after their own fashion the gods of their fathers." wrote Filippo Sassetti, who was in India from 1578 to 1588.

In 1620, an order was passed to prohibit Hindus from performing their marriage rituals.[73] An order was issued in June 1684 for suppressing the Konkani language and making it compulsory to speak Portuguese. The law provided for dealing harshly with anyone using the local languages. Following that law, all non-Catholic cultural symbols and books written in local languages were to be destroyed.[74] The French physician Charles Dellon experienced first-hand the cruelty of the Inquisition's agents, and complained about the goals, arbitrariness, torture and racial discrimination against the people of Indian origin, particularly Hindus.[75][1][5] He was arrested, served a prison sentence where he witnessed the torture and starvation Hindus were put through, and was released under the pressure of the French government. He returned to France and published a book in 1687 describing his experiences in Goa as Relation de l'Inquisition de Goa (The Inquisition of Goa).[75]

Persecution of Buddhists

The Goa Inquisition led the destruction of Buddhist sacred objects seized in Portuguese attacks in South Asia. In 1560, for example, an armada led by Viceroy Constantino de Bragança attacked Tamils in northeast Sri Lanka.[76] They seized a reliquary with Buddha's tooth preserved as sacred and called dalada by the local Tamils since the 4th-century. Diogo do Couto – the late 16th-century Portuguese chronicler in Goa, refers to the relic as "the monkey's tooth" (dente do Bugio) as well as "the Buddha's tooth", the "monkey" term being a common racial insult for the collective identity of South Asians.[76] In most European accounts of that era, Christian authors call it "monkey's or ape's tooth", while some call it "tooth of the demon" or "tooth of the holy man". In a few accounts, such as that of the Portuguese chronicler Faria e Sousa, the tooth is called "a genuine Satanic source of evil that had to be destroyed".[77] The tooth's capture by the Portuguese spread rapidly in South Asia, and the King of Pegu offered a fortune to Portuguese in exchange for it. However, the religious authorities of the Goa Inquisition prevented the acceptance of ransom and held a flamboyant ceremony to publicly destroy the tooth as a means of humiliation and religious cleansing.[76]

According to Hannah Wojciehowski, the "monkey" word became a racialized insult in the proceedings but it may initially have been a product of conflation of Hinduism and Buddhism, given the fact that the Buddha tooth relic was preserved and considered sacred by Tamil Hindus in Jaffna, and these Hindus also worshipped Hanuman.[78] To the Portuguese inquisition officials and their European supporters, the term projected their stereotypes for the lands and people they had violently conquered as well as their prejudices against Indian religions.[76]

Persecution of Jews

Goa was a sanctuary for Jews forcibly converted to Christianity in the Iberian peninsula. These forcibly baptized converts were known as New Christians. They lived in what came to be known then as the Jew street.[79] The New Christian population was so substantial that, as Savaira reveals,"in a letter dated Almeirim, February 18, 1519, King Manuel I promoted legislation henceforth prohibiting the naming of New Christians to the position of judge, town councilor or municipal registrar in Goa, stipulating, however, that those already appointed were not to be dismissed. This shows that even during the first nine years of Portuguese rule, Goa had a considerable influx of recently baptized Spanish and Portuguese Jews."[43] However, after the start of the Goa Inquisition, Viceroy Dom Antao de Noronha, in December 1565, issued an order that banned Jews from entering the Portuguese territories in India with violators liable to the penalties of arrest, seizure of their property and confinement in a prison.[79] The Portuguese built city fortification walls between 1564 and 1568. It ran adjacent to the Jew street, but placed it outside of the fort.[79]

The Inquisition originally targeted New Christians, that is Jews who had been force-converted to Christianity and who migrated from Portugal to India between 1505 and 1560.[1] Later it added in Moors, a term that meant Muslims who had previously invaded the Iberian peninsula from Morocco. In Goa, the Inquisition included Jews, Muslims and later predominantly Hindus.[48]

A documented case of the persecution of the Jews (New Christians) that began few years before the inauguration of the Goa Inquisition was that of a Goan woman named Caldeira. Her trial contributed to formal launch of Goa Inquisition office.[80]

Caldeira, and 19 other New Christians, were arrested by the Portuguese and brought before the tribunal in 1557. They were charged with Judaizing, visiting synagogues and eating unleavened bread.[80] She was also accused of celebrating Purim festival coincident with the Hindu festival of Holi, wherein she was alleged to have burnt dolls symbolic of "filho de hamam" (son of Haman).[80] Ultimately, all of them were sent from Goa to Lisbon to be tried by the Portuguese Inquisition. There, she was sentenced to death.[80]

The persecution of Jews extended to Portuguese territorial claims in Cochin. Their Synagogue (the Pardesi Synagogue) was destroyed by the Portuguese. The Kerala Jews rebuilt the Paradesi synagogue in 1568.[81]

Persecution of Goan Catholics

The Inquisition considered those who had converted to Catholicism and continued their former Hindu customs and cultural practices as heretics.[82][83] The Catholic missionaries aimed to eradicate indigenous languages such as Konkani and cultural practices such as ceremonies, fasts, growing of the tulsi plant in front of the house, the use of flowers and leaves for ceremony or ornament.[84]

There were other far reaching changes that took place during the occupation by the Portuguese, these included the prohibition of traditional musical instruments and singing of celebratory verses, which were replaced by Western music.[85]

People were renamed when they converted and not permitted to use their original Hindu names. Alcohol was introduced and dietary habits changed dramatically so that foods that were once taboo, such as pork shunned by Muslims and beef shunned by some sections of the Hindus, became part of the Goan diet.[84]

Nevertheless, many Goan Catholics continued some of their old cultural practices and Hindu customs.[82] Some of those accused of Crypto-Hinduism were condemned to death. Such circumstances forced many to leave Goa and settle in the neighboring kingdoms, of which a minority went to the Deccan and the vast majority went to Canara.[82][83]

Historian Severine Silva states that those who fled the Inquisition preferred to observe both Hindu customs and Catholic practices.[82]

As the persecution increased, missionaries complained that the Brahmins continued to perform the Hindu religious rites and Hindus defiantly increased their public religious ceremonies. This, alleged the missionaries, motivated the recently converted Goan Catholics to participate in Hindu ceremonies, and it was a reason offered for the alleged relapse.[86] In addition, states Délio de Mendonça, there was hypocritical difference between the preaching and practices of the Portuguese living in Goa. The Portuguese Christians and many clergymen were gambling, spending extravagantly, practicing public concubinage, extorting money from the Indians, engaging in sodomy and adultery. The "bad examples" of Portuguese Catholics were not universal and there were also "good examples" where some Portuguese Catholics offered medical care for the Goan Catholics who were sick. However, the "good examples" were not strong enough when compared to the "bad examples", and the Portuguese betrayed their belief in their cultural superiority and their assumptions that "Hindus, Muslims, barbarians and pagans did not possess virtues and goodness", states Mendonça.[86] Racial epithets such as negros (niggers) and cachorros (dogs) for the natives were commonly used by the Portuguese.[87]

In the later decades of the 250 year period of the Goa Inquisition, the Portuguese Catholic clergy discriminated against the Indian Catholic clergy descended from previously converted Catholic parents. The Goan Catholics were referred to as "black priests" and stereotyped to be "by their very nature ill-natured and ill-behaved, lascivious, drunkards, etc and therefore most unworthy of receiving the charge of the churches" in Goa.[87] Those who grew up as native Catholics were alleged by friars fearful of their careers and promotions, to have hate for "white skinned" people, suffering from "diabolic vice of pride" than the European proper. These racist accusations were grounds to keep the parishes and clergy institution of Goa under the monopoly of the Portuguese Catholics instead of allowing native Goa Catholics to rise in their ecclesiastical career based on merit.[87]

Suppression of Konkani

In stark contrast to the Portuguese priests' earlier intense study of the Konkani language and its cultivation as a communication medium in their quest for converts during the previous century, under the Inquisition, xenophobic measures were adopted to isolate new converts from the non-Catholic populations.[88] The use of Konkani was suppressed, while the colony suffered repeated Maratha attempts to invade Goa in the late 17th and earlier 18th centuries. These posed a serious threat to Portuguese control of Goa, and its maintenance of trade in India.[88] Due to the Maratha threat, Portuguese authorities decided to initiate a positive programme to suppress Konkani in Goa.[88] The use of Portuguese was enforced, and Konkani became a language of marginal peoples.[89]

Urged by the Franciscans, the Portuguese viceroy forbade the use of Konkani on 27 June 1684 and decreed that within three years, the local people in general would speak the Portuguese tongue. They were to be required to use it in all their contacts and contracts made in Portuguese territories. The penalties for violation would be imprisonment. The decree was confirmed by the king on 17 March 1687.[88] According to the Inquisitor António Amaral Coutinho's letter to the Portuguese monarch João V in 1731, these draconian measures did not meet with success.b[90] With the fall of the Province of the North (which included Bassein, Chaul and Salsette) to the Marathas in 1739, the Portuguese renewed their assault on Konkani.[88] On 21 November 1745, Archbishop Lourenço de Santa Maria decreed that applicants to the priesthood had to have knowledge of and the ability to speak in Portuguese; this applied not only to the pretendentes, but also for their close relations, as confirmed by rigorous examinations by reverend persons.[88] Furthermore, the Bamonns and Chardos were required to learn Portuguese within six months, failing which they would be denied the right to marriage.[88] In 1812, the Archbishop decreed that children were to be prohibited from speaking Konkani in schools and in 1847, this was extended to seminaries. In 1869, Konkani was completely banned in schools.[88]

As a result, Goans did not develop a literature in Konkani, nor could the language unite the population, as several scripts (including Roman, Devanagari and Kannada) were used to write it.[89] Konkani became the lingua de criados (language of the servants),[91] while the Hindu and Catholic elites turned to Marathi and Portuguese, respectively. Since India annexed Goa in 1961, Konkani has become the cement that binds all Goans across caste, religion and class; it is affectionately termed Konkani Mai (Mother Konkani).[89] The language received full recognition in 1987, when the Indian government recognised Konkani as the official language of Goa.[92]

Persecution of other Christians

In 1599 under Aleixo de Menezes, the Synod of Diamper forcefully converted the East Syriac Saint Thomas Christians (also known as Syrian Christians or Nasranis) of Kerala to the Roman Catholic Church. He had said that they held to Nestorianism, a christological position declared heretical by the Council of Ephesus.[14] The synod enforced severe restrictions on their faith and the practice of using Syriac/Aramaic. They were disfranchised politically and their Metropolitanate status was discontinued by blocking bishops from the East.[14] The persecution continued largely until the Coonan Cross oath and Nasrani rebellion in 1653, the eventual capture of Fort Kochi by the Dutch in 1663, and the resultant expulsion of Portuguese from Malabar.

The Goa Inquisition persecuted non-Portuguese Christian missionaries and physicians, such as those from France.[94] In the 16th-century, the Portuguese clergy became jealous of a French priest operating in Madras (now Chennai); they lured him to Goa, then had him arrested and sent to the inquisition. The French priest was saved when the Hindu King of a Karnataka kingdom interceded on his behalf by laying siege to St. Thome till the release of the priest.[94] Charles Dellon, the 18th-century French physician, was another example of a Christian arrested and tortured by the Goa Inquisition for questioning Portuguese missionary practices in India.[94][95][96] Dellon was imprisoned for five years by the Goa Inquisition before being released under the demands of France. Dellon described, states Klaus Klostermaier, the horrors of life and death at the Catholic Palace of the Inquisition that managed the prison and deployed a rich assortment of torture instruments per recommendations of the Church tribunals.[97]

There were assassination attempts against Archdeacon George, so as to subjugate the entire Church under Rome. The common prayer book was not spared. Books were burnt and any priest professing independence was imprisoned. Some altars were pulled down to make way for altars conforming to Catholic criteria.[14]

A few quotes on the Inquisition

Goa est malheureusement célèbre par son inquisition, également contraire à l'humanité et au commerce. Les moines portugais firent accroire que le peuple adorait le diable, et ce sont eux qui l'ont servi. (Goa is sadly famous for its inquisition, equally contrary to humanity and commerce. The Portuguese monks made us believe that the people worshiped the devil, and it is they who have served him.)

- Historian Alfredo de Mello describes the performers of Goan inquisition as,[100]

nefarious, fiendish, lustful, corrupt religious orders which pounced on Goa for the purpose of destroying paganism (ie Hinduism) and introducing the true religion of Christ.

See also

Notes

- a ^ The Papal bull Licet ab initio proclaimed an Apostolic constitution on 21 July 1542.[101][102]

- b ^ In his 1731 letter to King João V, the Inquisitor António Amaral Coutinho states:[90]

The first and the principal cause of such a lamentable ruin (perdition of souls) is the disregard of the law of His Majesty, Dom Sebastião of glorious memory, and the Goan Councils, prohibiting the natives to converse in their own vernacular and making obligatory the use of the Portuguese language: this disregard in observing the law, gave rise to so many and so great evils, to the extent of effecting irreparable harm to souls, as well as to the royal revenues. Since i have been though unworthy, the Inquisitor of this State, ruin has set in the villages of Nadorá (sic), Revorá, Pirná, Assonorá and Aldoná in the Province of Bardez; in the villages of Cuncolim, Assolná, Dicarpalli, Consuá and Aquem in Salcette; and in the island of Goa, in Bambolim, Curcá, and Siridão, and presently in the village of Bastorá in Bardez. In these places, some members of village communities, as also women and children have been arrested and others accused of malpractices; for since they cannot speak any other language but their own vernacular, they are secretly visited by botos, servants and high priests of pagodas who teach them the tenets of their sects and further persuade them to offer alms to the pagodas and to supply other necessary requisites for the ornament of the same temples, reminding them of the good fortune their ancestors had enjoyed from such observances and the ruin they were subjected to, for having failed to observe these customs; under such persuasion they are moved to offer gifts and sacrifices and perform other diabolical ceremonies, forgetting the law of Jesus Christ which they had professed in the sacrament of Holy Baptism. This would not have happened had they known only the Portuguese language; since they being ignorant of the native tongue the botos, grous (gurus) and their attendants would not have been able to have any communication with them, for the simple reason that the latter could only converse in the vernacular of the place. Thus an end would have been put to the great loss among native Christians whose faith has not been well grounded, and who easily yield to the teaching of the Hindu priests.

- The institution of Padroado dates to the 11th-century.[31] Similarly, Portuguese king's involvement in setting up, financing and militarily supporting Catholic Christian missionaries dates to centuries before the conquest and start of Portuguese Goa.[31] A number of Vatican bulls were issued to formalize this process before and after Portuguese Goa was established. For example, for the conquest of Ceuta where missionaries sailed with the Portuguese armada, the Inter Caetera bull of 1456, and the much later dated Praeclara Charissimi bull that bestowed upon the Portuguese king the responsibilities of "Grand Master of the military orders of Christ", and others.[32]

- Early texts use the term "the Roman fathers" for Jesuits. The first Jesuits arrived in Goa in 1540.[34]

- The percent data includes those charged with Crypto-Hinduism and where the caste is identified. For about 50% of the victims, this data is unavailable.[66]

References

- Glenn Ames (2012). Ivana Elbl (ed.). Portugal and its Empire, 1250-1800 (Collected Essays in Memory of Glenn J. Ames).: Portuguese Studies Review, Vol. 17, No. 1. Trent University Press. pp. 12–15 with footnotes, context: 11–32.

- "Goa Inquisition was most merciless and cruel". Rediff. 14 September 2005. Retrieved 14 April 2009.

- Lauren Benton (2002). Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900. Cambridge University Press. pp. 114–126. ISBN 978-0-521-00926-3.

- ANTÓNIO JOSÉ SARAIVA (1985), Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D. (Translators, 2001), The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill Academic, 2001), pp. 345–353.

- Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski (2011). Group Identity in the Renaissance World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–216 with footnotes 98–100. ISBN 978-1-107-00360-6.

- Gustav Henningsen; Marisa Rey-Henningsen (1979). Inquisition and Interdisciplinary History. Dansk folkemindesamling. p. 125.

- Maria Aurora Couto (2005). Goa: A Daughter's Story. Penguin Books. pp. 109–121, 128–131. ISBN 978-93-5118-095-1.

- Augustine Kanjamala (2014). The Future of Christian Mission in India: Toward a New Paradigm for the Third Millennium. Wipf and Stock. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-1-62032-315-1.

- Haig A. Bosmajian (2006). Burning Books. McFarland. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7864-2208-1.

- Rao, R.P. (1963). Portuguese Rule in Goa: 1510-1961. Asia Publishing House. p. 43.

- Coleridge, Henry James (1872). The Life and Letters of St. Francis Xavier. Burns and Oates. p. 268.

- ANTÓNIO JOSÉ SARAIVA (1985), Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D. (Translators, 2001), The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill Academic), pp. 107, 345-351

- Charles H. Parker; Gretchen Starr-LeBeau (2017). Judging Faith, Punishing Sin. Cambridge University Press. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-107-14024-0.

- Benton, Lauren. Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400–1900 (Cambridge, 2002), p. 122.

- Teotonio R. De Souza (1994). Discoveries, Missionary Expansion, and Asian Cultures. Concept. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-81-7022-497-6.

- Teotonio R. De Souza (1994). Goa to Me. Concept. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-81-7022-504-1.

- Rene J. Barendse (2009). Arabian Seas, 1700 - 1763. BRILL Academic. pp. 697–698. ISBN 978-90-04-17658-4.

- A Traveller's History of Portugal, by Ian Robertson (p. 69), Gloucestshire: Windrush Press, in association with London: Cassell & Co., 2002

- "Jewish Heritage: Portugal", Jewish Heritage in Europe

- John F. Chuchiak (2012). The Inquisition in New Spain, 1536–1820: A Documentary History. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 315–317. ISBN 978-1-4214-0449-3.

- Daus, Ronald (1983). Die Erfindung des Kolonialismus (in German). Wuppertal/Germany: Peter Hammer Verlag. pp. 81–82. ISBN 3-87294-202-6.

- Ana Cannas da Cunha (1995). A inquisição no estado da Índia: origens (1539-1560). Arquivos Nacionais/Torre do Tombo. pp. 1–16, 251–258. ISBN 978-972-8107-14-7.

- Ana E. Schaposchnik (2015). The Lima Inquisition: The Plight of Crypto-Jews in Seventeenth-Century Peru. University of Wisconsin Pres. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-0-299-30614-4.

- Aniruddha Ray (2016). Towns and Cities of Medieval India: A Brief Survey. Taylor & Francis. pp. 127–129. ISBN 978-1-351-99731-7.

- Teotónio de Souza (2015). "Chapter 10. Portuguese Impact upon Goa: Lusotopic, Lusophilic, Lusophonic?". In J. Philip Havik; Malyn Newitt (eds.). Creole Societies in the Portuguese Colonial Empire. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 204–207. ISBN 978-1-4438-8027-5.

- Teotonio R. De Souza (1989). Essays in Goan History. Concept Publishing. pp. 27 note 8. ISBN 978-81-7022-263-7.

- K. S. Mathew; Teotónio R. de Souza; Pius Malekandathil (2001). The Portuguese And The Socio-Cultural Changes In India, 1500-1800. Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities. p. 439. ISBN 978-81-900166-6-7.

- Daus (1983), "Die Erfindung", p. 33 (in German)

- John M. Flannery (2013). The Mission of the Portuguese Augustinians to Persia and Beyond (1602-1747). BRILL Academic. pp. 11–15 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-24382-8.

- Roger E. Hedlund, Jesudas M. Athyal, Joshua Kalapati, and Jessica Richard (2011). "Padroado". The Oxford Encyclopaedia of South Asian Christianity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198073857.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- John M. Flannery (2013). The Mission of the Portuguese Augustinians to Persia and Beyond (1602-1747). BRILL Academic. pp. 9–10 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-24382-8.

- John M. Flannery (2013). The Mission of the Portuguese Augustinians to Persia and Beyond (1602-1747). BRILL Academic. pp. 10–12 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-24382-8.

- Donald Frederick Lach; Edwin J. Van Kley (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe. University of Chicago Press. pp. 130–167, 890–891 with footnotes. ISBN 978-0-226-46767-2.

- Dauril Alden (1996). The Making of an Enterprise: The Society of Jesus in Portugal, Its Empire, and Beyond, 1540-1750. Stanford University Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-0-8047-2271-1.

- "Jews & New Christians in Portuguese Asia 1500-1700 Webcast | Library of Congress". loc.gov. Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2018.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Saraiva, Antonio. "The Marrano Factory" (PDF). ebooks.rahnuma.org. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Hayoun, Maurice R.; Limor, Ora; Stroumsa, Guy G.; Stroumsa, Gedaliahu A. G. (1996). Contra Iudaeos: Ancient and Medieval Polemics Between Christians and Jews. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161464829.

- Daus (1983), "Die Erfindung", pp. 61-66(in German)

- Aniruddha Ray (2016). Towns and Cities of Medieval India: A Brief Survey. Taylor & Francis. pp. 130–132. ISBN 978-1-351-99731-7.

- Délio de Mendonça (2002). Conversions and Citizenry: Goa Under Portugal, 1510-1610. Concept. pp. 382–385. ISBN 978-81-7022-960-5.

- Délio de Mendonça (2002). Conversions and Citizenry: Goa Under Portugal, 1510-1610. Concept. pp. 29, 111–112, 309–310, 321–323. ISBN 978-81-7022-960-5.

- Toby Green (2009). Inquisition: The Reign of Fear. Pan Macmillan. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-0-330-50720-2.

- António José Saraiva (2001). The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians 1536-1765. BRILL Academic. p. 348. ISBN 90-04-12080-7.

- Costa, Palmira Fontes da (3 March 2016). Medicine, Trade and Empire: Garcia de Orta's Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India (1563) in Context. Routledge. ISBN 9781317098171.

- Henry Charles Lea. "A History of the Inquisition of Spain, Volume 3". The Library of Iberian Resources Online. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- Hunter, William W, The Imperial Gazetteer of India, Trubner & Co, 1886

- Teotonio R. De Souza (2016). The Portuguese in Goa, in Acompanhando a Lusofonia em Goa: Preocupações e experiências pessoais (PDF). Lisbon: Grupo Lusofona. pp. 28–29.

- Lauren Benton (2002). Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900. Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-521-00926-3.

- Teotonio R. De Souza (2016). The Portuguese in Goa, in Acompanhando a Lusofonia em Goa: Preocupações e experiências pessoais (PDF). Lisbon: Grupo Lusofona. pp. 28–30.

- "Goa was birthplace of Indo-Western garments: Wendell Rodricks". Deccan Herald. New Delhi, India. 27 January 2012. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- History of Christians in Coastal Karnataka, 1500–1763 A.D., Pius Fidelis Pinto, Samanvaya, 1999, p. 134

- Lauren Benton (2002). Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900. Cambridge University Press. pp. 120–123. ISBN 978-0-521-00926-3.

- Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians, Alan Machado Prabhu, I.J.A. Publications, 1999, p. 121

- Bethencourt, Francisco (1992). "The Auto da Fe: Ritual and Imagery". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. The Warburg Institute. 55: 155–168. doi:10.2307/751421. JSTOR 751421.

- Teotonio R. De Souza (1994). Discoveries, Missionary Expansion, and Asian Cultures. Concept Publishing. pp. 79–82. ISBN 978-81-7022-497-6.

- Teotonio R. De Souza (1994). Discoveries, Missionary Expansion, and Asian Cultures. Concept. pp. 79–82. ISBN 978-81-7022-497-6.

- Sakshena, R.N, Goa: Into the Mainstream (Abhinav Publications, 2003), p. 24

- M. D. David (ed.), Western Colonialism in Asia and Christianity, Bombay, 1988, p.17

- Haig A. Bosmajian (2006). Burning Books. McFarland. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-7864-2208-1.

- António José Saraiva (2001). The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians 1536-1765. BRILL Academic. pp. 352–354. ISBN 90-04-12080-7.

- Priolkar, Anant Kakba; Dellon, Gabriel; Buchanan, Claudius; (1961), The Goa Inquisition: being a quatercentenary commemoration study of the Inquisition in India, Bombay University Press, pp. 114-149

- Priolkar, Anant Kakba; Dellon, Gabriel; Buchanan, Claudius; (1961), The Goa Inquisition: being a quatercentenary commemoration study of the Inquisition in India, Bombay University Press, pp. 87-99, 114-149

- Ivana Elbl (2009). Portugal and its Empire, 1250-1800 (Collected Essays in Memory of Glenn J. Ames): Portuguese Studies Review, Vol. 17, No. 1. Baywolf Press (Republished 2012). pp. 14–15.

- Shirodhkar, P. P., Socio-Cultural life in Goa during the 16th century, p. 123

- Robert M. Hayden; Aykan Erdemir; Tuğba Tanyeri-Erdemir; Timothy D. Walker; et al. (2016). Antagonistic Tolerance: Competitive Sharing of Religious Sites and Spaces. Routledge. pp. 142–145. ISBN 978-1-317-28192-4.

- António José Saraiva (2001). The Marrano Factory: The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians 1536-1765. BRILL Academic. pp. 352–357. ISBN 90-04-12080-7.

- Serrão, José Vicente; Motta, Márcia; Miranda, Susana Münch (2016). Serrão, José Vicente; Motta, Márcia; Miranda, Susana Münch (eds.). "Dicionário da Terra e do Território no Império Português". E-Dicionário da Terra e do Território no Império Português. 4. Lisbon: CEHC-IUL. doi:10.15847/cehc.edittip.2013ss. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rene Barendse (2009). Arabian Seas 1700 - 1763 (4 vols.). BRILL Academic. pp. 1406–1407. ISBN 978-90-474-3002-5.

- Jorge Manuel Flores (2007). Re-exploring the Links: History and Constructed Histories Between Portugal and Sri Lanka. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 117–121. ISBN 978-3-447-05490-4.

- Andrew Spicer (2016). Parish Churches in the Early Modern World. Taylor & Francis. pp. 309–311. ISBN 978-1-351-91276-1.

- Teotonio R. De Souza (2016). The Portuguese in Goa, in Acompanhando a Lusofonia em Goa: Preocupações e experiências pessoais (PDF). Lisbon: Grupo Lusofona. pp. 28–30.

- Ulrich L. Lehner (2016). The Catholic Enlightenment: The Forgotten History of a Global Movement. Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-19-023291-7.

- "Recall the Goa Inquisition to stop the Church from crying foul". Rediff. India. 16 March 1999.

- http://pt.scribd.com/doc/28411503/Goa-Inquisition-for-Colonial-Disciplining

- L'Inquisition de Goa: la relation de Charles Dellon (1687), Archive

- Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski (2011). Group Identity in the Renaissance World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32–33, 187–193. ISBN 978-1-107-00360-6.

- Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski (2011). Group Identity in the Renaissance World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–201. ISBN 978-1-107-00360-6.

- Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski (2011). Group Identity in the Renaissance World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 187–199. ISBN 978-1-107-00360-6.

- Liam Matthew Brockey (2016). Portuguese Colonial Cities in the Early Modern World. Taylor & Francis. pp. 54–56. ISBN 978-1-351-90982-2.

- Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski (2011). Group Identity in the Renaissance World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 208–215. ISBN 978-1-107-00360-6.

- Hannah Chapelle Wojciehowski (2011). Group Identity in the Renaissance World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 212–214 with Figure 4.8. ISBN 978-1-107-00360-6.

- The Marriage Customs of the Christians in South Canara, India – pp. 4–5, Severine Silva and Stephen Fuchs, 1965, Asian Folklore Studies, Nanzan University (Japan)

- Farias, Kranti K. (1999). The Christian Impact in South Kanara. Mumbai: Church History Association of India. pp. 34–36.

- Mascarenhas-Keyes, Stella (1979), Goans in London: portrait of a Catholic Asian community, Goan Association (U.K.)

- Robinson, Rowina (2003), Christians of India, SAGE,

- Délio de Mendonça (2002). Conversions and Citizenry: Goa Under Portugal, 1510-1610. Concept Publishing. pp. 308–310. ISBN 978-81-7022-960-5.

- Teotónio de Souza (2015). "Chapter 10. Portuguese Impact upon Goa: Lusotopic, Lusophilic, Lusophonic?". In J. Philip Havik; Malyn Newitt (eds.). Creole Societies in the Portuguese Colonial Empire. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 206–208. ISBN 978-1-4438-8027-5.

- Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians, Alan Machado Prabhu, I.J.A. Publications, 1999, pp. 133–134

- Newman, Robert S. (1999), The Struggle for a Goan Identity, in Dantas, N., The Transformation of Goa, Mapusa: Other India Press, p. 17

- Priolkar, Anant Kakba; Dellon, Gabriel; Buchanan, Claudius; (1961), The Goa Inquisition: being a quatercentenary commemoration study of the inquisition in India, Bombay University Press, p. 177

- Routledge, Paul (22 July 2000), "Consuming Goa, Tourist Site as Dispencible space", Economic and Political Weekly, 35, p. 264

- "Goa battles to preserve its identity", Times of India, 16 May 2010

- Gabriel Dellon; Charles Amiel; Anne Lima (1997). L'Inquisition de Goa: la relation de Charles Dellon (1687). Editions Chandeigne. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-2-906462-28-1.

- Lauren Benton (2002). Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900. Cambridge University Press. pp. 121–123. ISBN 978-0-521-00926-3.

- Lynn Avery Hunt; Margaret C. Jacob; W. W. Mijnhardt (2010). The Book that Changed Europe: Picart & Bernard's Religious Ceremonies of the World. Harvard University Press. pp. 207–209. ISBN 978-0-674-04928-4.

- Gabriel Dellon; Charles Amiel; Anne Lima (1997). L'Inquisition de Goa: la relation de Charles Dellon (1687). Editions Chandeigne. pp. 21–56. ISBN 978-2-906462-28-1.

- Klaus Klostermaier (2009). "Facing Hindu Critique of Christianity". Journal of Ecumenical Studies. 44 (3): 461–466.

- Oeuvres completes de Voltaire – Volume 4, Page 786

- Oeuvres complètes de Voltaire, Volume 5, Part 2, Page 1066

- Memoirs of Goa by Alfredo DeMello

- Bullarum diplomatum et privilegiorum santorum romanorum pontificum, Augustae Taurinorum : Seb. Franco et Henrico Dalmazzo editoribus

- Christopher Ocker (2007). Politics and Reformations: Histories and Reformations. BRILL Academic. pp. 91–93. ISBN 978-90-04-16172-6.

Bibliography

- Richard Zimler. Guardian of the Dawn (Delta Publishing, 2005).

- Benton, Lauren. Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400–1900 (Cambridge, 2002).

- D'Costa Anthony, S.J. The Christianisation of the Goa Islands, 1510-1567 (Bombay, 1965).

- Hunter, William W. The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Trubner & Co, 1886).

- Priolkar, A. K. The Goa Inquisition (Bombay, 1961).

- Sakshena, R. N. Goa: Into the Mainstream (Abhinav Publications, 2003).

- Saraiva, Antonio Jose. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill, 2001).

- Shirodhkar, P. P. Socio-Cultural life in Goa during the 16th century.

Further reading

- App, Urs. The Birth of Orientalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010 (hardcover, ISBN 978-0-8122-4261-4); contains a 60-page chapter (pp. 15–76) on Voltaire as a pioneer of Indomania and his use of fake Indian texts in anti-Christian propaganda.

- Zimler, Richard. Guardian of the Dawn Constable & Robinson, (ISBN 1-84529-091-7) An award-winning historical novel set in Goa that explores the devastating effect of the Inquisition on a family of secret Jews.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Goa Inquisition |

- Relation de l'inquisition de Goa, Gabriel Delon (1688, in French)

- The history of the Inquisition, as it is exercised at Goa written in French, by the ingenious Monsieur Dellon, who laboured five years under those severities ; with an account of his deliverance ; translated into English, Henry Wharton (1689) (Large file, University of Michigan Archives)

- An account of the Inquisition at Goa, in India by Gabriel Dellon (Re-translated in 1819)

- Flight of the Deities: Hindu Resistance in Portuguese Goa Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 30, No. 2. (May, 1996), pp. 387–421

- Repression of Buddhism in Sri Lanka by the Portuguese (1505 - 1658)