Greece in the Roman era

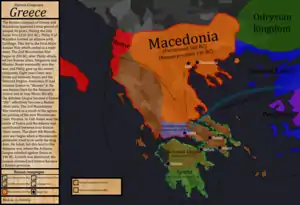

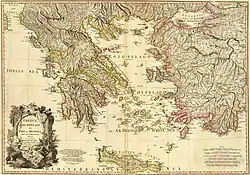

Greece in the Roman era describes the Roman conquest of Greece and the period of Greek history when Ancient Greece was dominated by the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire (27 BC – AD 1453), commonly referred to as the Byzantine Empire after about AD 395. The Roman era of Greek history began with the Corinthian defeat in the Battle of Corinth in 146 BC. However, before the Achaean War, the Roman Republic had been steadily gaining control of mainland Greece by defeating the Kingdom of Macedon in a series of conflicts known as the Macedonian Wars. The Fourth Macedonian War ended at the Battle of Pydna in 148 BC and defeat of the Macedonian royal pretender Andriscus.

The definitive Roman occupation of the Greek world was established after the Battle of Actium (31 BC), in which Augustus defeated Cleopatra VII, the Greek Ptolemaic queen of Egypt, and the Roman general Mark Antony, and afterwards conquered Alexandria (30 BC), the last great city of Hellenistic Greece.[1] The Roman era of Greek history continued with Emperor Constantine the Great's adoption of Byzantium as Nova Roma, the capital city of the Roman Empire; in AD 330, the city was renamed Constantinople. Afterwards, the Byzantine Empire was in general a polity Greek in culture and language.

Roman Republic

The Greek peninsula fell to the Roman Republic during the Battle of Corinth (146 BC), when Macedonia became a Roman province. Meanwhile, southern Greece also came under Roman hegemony, but some key Greek poleis remained partly autonomous and avoided direct Roman taxation. The Hellenistic Kingdom of Pergamon (282–133 BC) was annexed to that territory in 133 BC, when King Attalus III (r. 138–133 BC) willed the lands to Rome,[2] but the Romans were slow in securing their claim to those lands, and a pretender to the throne of Pergamon, Eumenes III (Aristonicus) led a revolt with the help of the philosopher Blossius, which the Roman army suppressed in 129 BC, when the lands of Pergamon were divided among Rome, the Kingdom of Pontus, and Cappadocia.

In 88 BC, Athens and other Greek city-states revolted against Rome and were suppressed by General Lucius Cornelius Sulla. During the Roman civil wars, Greece was physically and economically devastated until Augustus organised the peninsula as the province of Achaea, in 27 BC. Initially, Rome's conquest of Greece damaged the economy, but it readily recovered under Roman administration in the postwar period. Moreover, the Greek cities in Asia Minor recovered from the Roman conquest more rapidly than the cities of peninsular Greece, which had been much damaged in the war with Sulla.

As an empire, Rome invested resources and rebuilt the cities of Roman Greece, and established Corinth as the capital city of the province of Achaea, and Athens prospered as a cultural hub of philosophy, education and learned knowledge.

Early Roman Empire

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Greece |

|

|

|

Life in Greece continued under the Roman Empire much the same as it had previously. Roman culture was highly influenced by the Greeks; as Horace said, Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit ("Captive Greece captured her rude conqueror").[3] The epics of Homer inspired the Aeneid of Virgil, and authors such as Seneca the Younger wrote using Greek styles. Some Roman nobles regarded the Greeks as backwards and petty, but many others embraced Greek literature and philosophy. The Greek language became a favorite of the educated and elite in Rome, such as Scipio Africanus, who tended to study philosophy and regarded Greek culture and science as an example to be followed.

The Roman Emperor Nero visited Greece in AD 66, and performed at the Ancient Olympic Games, despite the rules against non-Greek participation. He was honoured with a victory in every contest, and in the following year, he proclaimed the freedom of the Greeks at the Isthmian Games in Corinth, just as Flamininus had over 200 years previously. Hadrian was also particularly fond of the Greeks; before he became emperor he had served as an eponymous archon of Athens. He also finished the Temple of Zeus there and the Athenians built the Arch of Hadrian in his honour nearby.

Many temples and public buildings were built in Greece by emperors and wealthy Roman nobility, especially in Athens. Julius Caesar began construction of the Roman agora in Athens, which was finished by Augustus. The main gate, the Gate of Athena Archegetis, was dedicated to the patron goddess of Athens, Athena. The Agrippeia was built in the centre of the Ancient Agora of Athens by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa. Emperor Hadrian was a philhellene and an ardent admirer of Greece and, seeing himself as an heir to Pericles, made many contributions to Athens. He built the Library of Hadrian in the city and completed the construction of the Temple of Olympian Zeus, some 638 years after its construction had been started by Athenian tyrants but ended because of the belief that building on such a scale would cause hubris. The Athenians built the Arch of Hadrian to honor Emperor Hadrian. The side of the arch facing the Athenian agora and the Acropolis had an inscription stating, "This is Athens, the ancient city of Theseus." The side facing the Temple of Zeus and the 'new city' (this was still part of the ancient city; e.g. the Panathenaic Stadium has always been on that side) had an inscription stating, "This is the city of Hadrian, and not of Theseus". Adrianou (Hadrian Street) exists to this day, leading from the arch to the Ancient Agora.

The Pax Romana was the longest period of peace in Greek history, and Greece became a major crossroads of maritime trade between Rome and the Greek speaking eastern half of the empire. The Greek language served as a lingua franca in the East and in Italy, and many Greek intellectuals such as Galen would perform most of their work in Rome.

During this time, Greece and much of the rest of the Roman east came under the influence of Early Christianity. The apostle Paul of Tarsus preached in Philippi, Corinth and Athens, and Greece soon became one of the most highly Christianized areas of the empire.

Later Roman Empire

During the 2nd and 3rd centuries, Greece was divided into provinces including Achaea, Macedonia, Epirus and Thrace. During the reign of Diocletian in the late 3rd century, Moesia was organized as a diocese, and was ruled by Galerius. Under Constantine (who professed Christianity) Greece was part of the prefectures of Macedonia and Thrace. Theodosius divided the prefecture of Macedonia into the provinces of Creta, Achaea, Thessalia, Epirus Vetus, Epirus Nova, and Macedonia. The Aegean islands formed the province of Insulae in the Diocese of Asia.

Greece faced invasions from the Heruli, Goths, and Vandals during the reign of Romulus Augustulus. Stilicho, who pretended he was a regent for Arcadius, evacuated Thessaly when the Visigoths invaded in the late 4th century. Arcadius' chief advisor Eutropius allowed Alaric to enter Greece, and he looted Athens, Corinth and the Peloponnese. Stilicho eventually drove him out around 397 and Alaric was made magister militum in Illyricum. Eventually, Alaric and the Goths migrated to Italy, sacked Rome in 410, and built the Visigothic Kingdom in Iberia, which lasted until 711 with the advent of the Arabs.

Greece remained part of the relatively cohesive and robust eastern half of the empire, which eventually became the center of the remaining Roman Empire, the Eastern Roman now referred to as Byzantine Empire. Contrary to outdated visions of Late Antiquity, the Greek peninsula was most likely one of the most prosperous regions of the Roman Empire. Older scenarios of poverty, depopulation, barbarian destruction, and civil decay have been revised in light of recent archaeological discoveries.[4] In fact the polis, as an institution, appears to have remained prosperous until at least the 6th century. Contemporary texts such as Hierokles' Syndekmos affirm that late antiquity Greece was highly urbanised and contained approximately eighty cities.[4] This view of extreme prosperity is widely accepted today, and it is assumed between the 4th and 7th centuries AD, Greece may have been one of the most economically active regions in the eastern Mediterranean.[4]

References

- Hellenistic Age. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2013. Archived here.

- Livy: Periochae 58

- "Horace - Wikiquote". en.wikiquote.org. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- Rothaus, p. 10. "The question of the continuity of civic institutions and the nature of the polis in the late antique and early Byzantine world have become a vexed question, for a variety of reasons. Students of this subject continue to contend with scholars of earlier periods who adhere to a much-outdated vision of late antiquity as a decadent decline into impoverished fragmentation. The cities of late-antique Greece displayed a marked degree of continuity. Scenarios of barbarian destruction, civic decay, and manorialization simply do not fit. In fact, the city as an institution appears to have prospered in Greece during this period. It was not until the end of the 6th century (and maybe not even then) that the dissolution of the city became a problem in Greece. If the early 6th century Syndekmos of Hierokles is taken at face value, late-antique Greece was highly urbanized and contained approximately eighty cities. This extreme prosperity is born out by recent archaeological surveys in the Aegean. For late-antique Greece, a paradigm of prosperity and transformation is more accurate and useful than a paradigm of decline and fall."

Sources

- Bernhardt, Rainer (1977). "Der Status des 146 v. Chr. unterworfenen Teils Griechenlands bis zur Einrichtung der Provinz Achaia". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte (in German). 26 (1): 62–73. JSTOR 4435542.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boardman, John The Oxford History of Greece & the Hellenistic World 2nd Edition Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-280137-6

- Rothaus, Richard M. Corinth: The First City of Greece. Brill, 2000. ISBN 90-04-10922-6

- Francis, Jane E. and Anna Kouremenos Roman Crete: New Perspectives. Oxford: Oxbow, 2016. ISBN 978-1-78570-095-8