Imatong Mountains

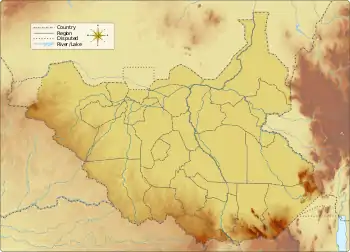

The Imatong Mountains (also Immatong, or rarely Matonge) are mainly located in Imatong State in southeastern South Sudan, and extend into the Northern Region of Uganda. It was earlier a part of Eastern Equatoria before reorganisation of states.

| Imatong Mountains | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,071 m (6,795 ft) |

| Geography | |

Location in South Sudan | |

| Country | |

| State | Imatong State |

| Range coordinates | 3°57′0″N 32°54′0″E |

Mount Kinyeti is the highest mountain of the range at 3,187 metres (10,456 ft), and the highest point of South Sudan.[1]

The range has an equatorial climate and had dense montane forests supporting diverse wildlife. Since the mid-20th century the rich ecology has increasingly been severely degraded by native forest clearance and subsistence farming, causing extensive erosion of the slopes.[2]

Geography

The Imatong Mountains massif lies mainly within Torit County (western part) and Ikotos County (eastern part) of Imatong State. It is located some 190 kilometres (120 mi) southeast of Juba and south of the main road from Torit to the Kenyan border town of Lokichoggio.[3]

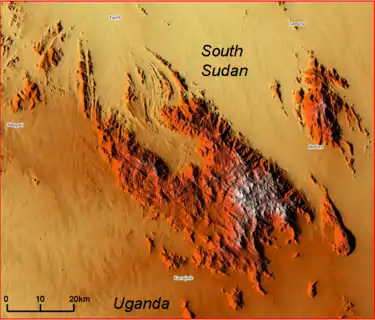

The mountain range rises steeply from the surrounding plains, which slope gradually down from about 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) on the South Sudan-Uganda border in the south to 600 metres (2,000 ft) at Torit in the north.

These plains are crossed by many streams, separated by low, rounded ridges, and dotted with small gneiss hills, outliers of the main mountain range.[4]

The mountains are formed of crystalline basement rock that rises through the Tertiary and Quaternary unconsolidated deposits of the plains in the South Sudan-Uganda frontier zone. The most widespread types of rock are leucocratic gneisses rich in quartz.[5] The mountains are sharply faulted and are the source of many year-round rivers.[3]

The mountains are highest in the southeast where a group of peaks reach about 3,000 metres (9,800 ft), and the tallest, Mount Kinyeti, reaches 3,187 metres (10,456 ft).[4] This central block group of high mountains around Mount Kinyeti are sometimes called the Lomariti or Lolibai mountains, and the high central part on the Uganda side is sometimes called the Lomwaga Mountains.[6]

Sub-ranges

The Modole or Langia mountains in the southeast of the central block are separated from the lower Teretenya ridge to the east by the Shilok River, a tributary of the Koss river.[7]

Sub-ranges run to the northwest, west, and southwest of the central block, The northwest and west ranges are separated by the Kinyeti River valley, and the west and southwest ranges by the Ateppi valley. The ranges are generally about 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) high, with peaks rising to 2,400 metres (7,900 ft).[4] The northwestern chain culminates in Mount Garia and Mount Konoro, both about 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) high, rising above the villages of Gilo and Katire. The western chain, with peaks rising up to 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) high, is usually known as the Acholi Mountains. The southwestern chain extending into Uganda is often called the Agoro Mountains.[8]

Watersheds

The Kinyeti River and other streams that drain the northern slopes of the mountains feed the Badigeru Swamps, which are 100 kilometres (62 mi) long and up to 25 kilometres (16 mi) wide at high water, but generally only 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) wide. Some of the water from the northern end of this swamp may filter eastward to the Veveno River, then via the Sobat River to the White Nile. Some of the water may filter westward to the Bahr el Jebel section of the White Nile.[9] To the south and west the mountains are drained by the fast-flowing Aswa River / Ateppi system. To the northeast the mountains are drained by the Koss River, which flows between the Imatongs and the Dongotona Hills. [10]

Ecology

Average annual rainfall in the Imatong range is about 1,500 millimetres (4.9 ft). Some of the mountain range's habitat is semi-protected within the Imatong Central Forest Reserve.

Flora

The plains and the lower parts of the mountains are covered by deciduous woodland, wooded grassland and bamboo thickets to the north and west. The areas to the east and southeast are in the rain shadow of the mountains, with dry subdesert grassland or deciduous or semi-evergreen bush.[7] The mountains have rich diversity of flora, with hundreds of species that are found nowhere else in South Sudan. Their diversity is due to their position between the West African rain forest, the Ethiopian plateau and the East African mountains, coupled with their relative isolation for long periods during which new species could emerge.[11]

Vegetation in the lower areas includes woodlands of Albizia and Terminalia, and mixed Khaya lowland semi-evergreen forest up to 1,000 metres (3,300 ft).[3] Above 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) there is montane forest with Podocarpus, Croton, Macaranga and Albizia up to 2,900 metres (9,500 ft).[3] The levels above 2,500 metres (8,200 ft) do not seem to have ever been inhabited by humans, but have been visited by honey-gatherers and hunters, and the fires they have started have destroyed the forest on many hill tops.[12] At the highest levels, the forest is replaced by Hagenia woodland, Erica (heather) thicket and areas of bamboo.[3]

Fauna

According to a 1984 report, the mountains supported abundant wildlife, including healthy populations of colobus and blue monkey, bush-pig and a local sub-species of bushbuck. The south eastern Kipia and Lomwaga Uplands were least visited by hunters and had the largest populations of elephant, buffalo, duiker's, hyaena and leopard.[13]

Mammals that normally inhabit a forest environment show greatest differentiation from similar mammals elsewhere, probably due to isolation of the Imatong forests from other forests by wide areas of semi-arid savanna. This isolation dates back to the last Pleistocene Pluvial period about 12,000 years ago.[14] The forest contains many birds found in no other part of South Sudan, and is a resting place for European songbirds en route to their overwintering places in East Africa.[13]

Birdlife includes the endangered spotted ground-thrush Zoothera guttata.[3]

People

The villages and settlements of the region are inhabited by Nilotic people including Lotuko in the east, Acholi in the west and Lango in the southern part.[3] They practice subsistence farming and raise some livestock.

The people of the area mostly live on the plains at the foot of the mountains, but recently they have been forced to move into the mountains as high as 2,300 metres (7,500 ft) to find land for farming. Their agricultural practices have led to serious erosion of the steep slopes.[3]

Relatively small numbers of the people practice Christianity.[15] Foreign Christian missionaries have been entering the remote mountainous areas since 2005.[16]

European explorations

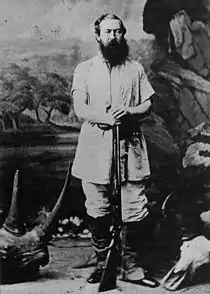

Little is known of the area before the arrival of Europeans. The explorer Samuel Baker was the first European to visit the region, travelling in the northwest and west of the area in 1863. He visited Tarrangolle (Tirangole), and observed then unnamed mountains to the south. Later he passed through them, the present-day western Acholi sub-range of the Imatongs.

Emin Pasha made a trip in 1881 in which he traveled along the eastern foothills of the mountains and then southwest to the White Nile.[17] J.R.L. Macdonald passed through the region in 1898 on a patrol towards Lado, and later the Ugandan colonial government established a post at Ikotos, just east of the mountain range.[18]

After 1929 the British established an observation post on the north side of the range, above the village of Gilo (1800 m) at an altitude of about 2,200 metres (7,200 ft).

- Maps

The official map of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan published in 1922 only showed the outlines of the mountains.[17] The first map to show the mountain range and give it the name Imatong Mountains was published in the Geographical Journal in May 1929. It was prepared from a compilation of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Government Survey Department. The first detailed map of the mountain range appeared in 1931.[17]

- Botanists and biologists

Apart from a field visit by R. Good to Gebel Marra, that obtained only a few specimens, no European botanists had investigated the mountain range's flora before 1929.[19] In that year the botanist Thomas Ford Chipp, then deputy director of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, reached the summit of Kinyeti peak. Later that year he published a report on the flora with several photographs. The biologist Neal A. Weber examined the ants in the area in 1942/1943.[20]

Civil wars

The mountains were a haven for the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) during the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005). In 1986 the government of Sudan started to provide arms, training and sanctuary for the LRA, who began to raid and plunder villages along the then Sudan–Uganda border. The secessionist Sudan People's Liberation Army assisted the Uganda People's Defence Force in fighting back.[21] The struggle dragged on for over twenty years. Over 400 people were massacred by the LRA in the Imotong area in March 2002.[22] The LRA finally withdrew from the region in April 2007.[16]

Years of civil war have made violence commonplace, most people have experienced the murder of a close family member. According to a 2010 report, "interviews suggested that at least every male community member over 20 years of age owns a gun in Ikotos, with some households having as many as eight to nine guns ... 33 per cent of all crimes were reportedly carried out with an AK-47 or similar automatic rifle".[23]

Since the Second Sudanese Civil War ended in 2005, more foreign aid workers began spending time in the region. [16] The range became part of South Sudan when the country was established in 2011.

Agricultural impact

The British colonial administration of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan began a forestry project in the Kinyeti basin in the 1940s. They cleared the native trees and natural forest habitats, to plant fast-growing softwoods, such as cypress-pines, for lumber.

In 1950 the mountain range's habitats above 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) were placed within the Imatong Central Forest Reserve, with no further settlement permitted. The reserve was not protected and the settlement ban was not enforced during the civil wars. Forestry brought laborers into the mountains, and they started hillside farming in a wide area around the forest plantations. Forestry was then neglected during the First Sudanese Civil War (1955–1972), after the 1956 independence of Sudan.

After 1972 an effort was made to rehabilitate the softwood tree plantations, with a new road built from Torit, a hydro-electric scheme developed to power sawmills, and other changes.

As of 1984 only the steepest slopes had natural forest and there were plans to clear-cut most of the Kinyeti basin.[12] In 1984 only the Acholi mountains sub-range in the west, and the inaccessible area south east of Mount Kinyeti, were still relatively unaffected.[12]

The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005) caused further ecological disruption and decline of habitats.

Erosion

Erosion was very visible on farms established on steep hillsides by people who had moved into the mountains after the 1940s. Fingermillet was the last crop, grown on what soil remained among the rocks and giving a scanty yield.[24] Erosion could have been greatly reduced agricultural terraces, but needed construction efforts not done. The Imatong softwoods forestry project let farm laborers plant crops between young trees for two years, reducing erosion and improving crop yields while also producing wood, but only in the first years.[25]

Farming continued causing erosion, and in 1984 was evident by muddiness of the Kinyeti River in the rainy season downstream from a potato project. A tea project was launched at Upper Talinga in 1975, opening a route for people to move into the mountains through the Ateppi valley. The result was an increase in hunting, hillside farming, and erosion.

Conservation

A project was launched in 2009 where the Wildlife Conservation Society worked with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry to evaluate the impact of humans on the mountain ecology and to develop a plan for land use that balances the needs of communities, commercial plantations and conservation of biodiversity. The project makes extensive use of satellite imagery, combined with field observations to map changes to forest coverage. This has confirmed continued forest clearance.[26] A proposal has been made to convert part of the Imatong Central Forest Reserve, which lies within the range, into a National Park, designating the remainder as a buffer zone.[3]

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Van Noordwijk 1984, pp. 217ff.

- Birdlife.

- Jackson 1956.

- Jenkin et al 1977.

- Friis & Vollesen 1998, pp. 9.

- Friis & Vollesen 1998, pp. 11.

- Friis & Vollesen 1998, pp. 9–10.

- Hughes & Hughes 1992, pp. 224.

- Yongo-Bure 2007, pp. 21.

- Van Noordwijk 1984, pp. 218.

- Van Noordwijk 1984, pp. 221.

- Van Noordwijk 1984, pp. 220.

- Setzer 1956, pp. 451ff.

- Jenkins.

- Lutheran World Federation.

- Friis & Vollesen 1998, pp. 20–23.

- Hill 1967, pp. 216.

- Chipp 1929.

- Taylor.

- Burr & Collins 2003, pp. 108.

- Ochan 2007.

- Symptoms and Causes.

- Van Noordwijk 1984, pp. 186.

- Van Noordwijk 1984, pp. 188.

- PlanetAction.

Sources

- Burr, Millard; Collins, Robert O. (2003). Revolutionary Sudan: Hasan al-Turabi and the Islamist state, 1989–2000. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-13196-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- BirdLife International. "SD020 Imatong mountains". Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. "Imatong Mountains". Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- Chipp, T.F. (1929). "The Imatong Mountains, Sudan". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 1929 (6): 177–197. doi:10.2307/4115389. JSTOR 4115389.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friis, Ib; Vollesen, Kaj (1998). Flora of the Sudan-Uganda border area east of the Nile. Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab. ISBN 87-7304-297-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, Richard Leslie (1967). A biographical dictionary of the Sudan. Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-1037-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, R. H.; Hughes, J. S. (1992). A directory of African wetlands. IUCN. ISBN 2-88032-949-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, J.K. (July 1956). "The Vegetation of the Imatong Mountains, Sudan". Journal of Ecology. 44 (2): 341–374. doi:10.2307/2256827. JSTOR 2256827.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkin, R N; Howard, W J; Thomas, P; Abel, T M B; Deane, G C (1977). "Forestry development prospects in the Imatong Central Forest Reserve, Southern Sudan Volume 1 Summary" (PDF). Ministry of Overseas Development (UK). Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- Jenkins, Orville. "Nilotic People Group Tree". Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- Lutheran World Federation (7 May 2008). "Sudan: Assistance to Returnees & Local Communities in Ikotos and Kapoeta Counties – AFSD82" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- Ochan, Clement (December 2007). "Responding to Violence in Ikotos County, South Sudan: Government and Local Efforts to Restore Order" (PDF). Feinstein International Center. Retrieved 2011-07-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Planet Action Report Summary for Sudan / Imatong Mountains Project" (PDF). Planet Action. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-04. Retrieved 2011-07-12.

- Setzer, Henry W. (1956). "Mammals of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan" (PDF). Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 106 (3377): 447–587. doi:10.5479/si.00963801.106-3377.447. Retrieved 2011-07-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Symptoms and causes: Insecurity and underdevelopment in Eastern Equatoria" (PDF). Small Arms Survey. 16. April 2010. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- Taylor, Brian. "Chapter 2 – Geography and History – Northeast Africa – Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, Ethiopia & Somalia". The Ants of Africa. Archived from the original on 2011-07-09. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- Van Noordwijk, Meine (1984). Ecology textbook for the Sudan (PDF). Khartoum University Press. ISBN 90-6224-114-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yongo-Bure, Benaiah (2007). Economic development of southern Sudan. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-3588-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)