Latvian orthography

Latvian orthography historically used a system based upon German phonetic principles, while the Latgalian dialect was written using Polish orthographic principles. The present-day Latvian orthography was developed by the Knowledge Commission of the Riga Latvian Association in 1908, and was approved the same year by the orthography commission under the leadership of Kārlis Mīlenbahs and Jānis Endzelīns.[1] Its basis is the Latin script and it was introduced by law from 1920 to 1922 in the Republic of Latvia. For the most part it is phonetic in that it follows the language's pronunciation.

Alphabet

Today, the Latvian standard alphabet consists of 33 letters.

| Majuscule forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A | Ā | B | C | Č | D | E | Ē | F | G | Ģ | H | I | Ī | J | K | Ķ | L | Ļ | M | N | Ņ | O | P | R | S | Š | T | U | Ū | V | Z | Ž |

| Minuscule forms (also called lowercase or small letters) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | ā | b | c | č | d | e | ē | f | g | ģ | h | i | ī | j | k | ķ | l | ļ | m | n | ņ | o | p | r | s | š | t | u | ū | v | z | ž |

| Names of Letters | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | garais ā | bē | cē | čē | dē | e | garais ē | ef | gā | ģē | hā | i | garais ī | jē | kā | ķē | el | eļ | em | en | eņ | o | pē | er | es | eš | tē | u | garais ū | vē | zē | žē |

The modern standard Latvian alphabet uses 22 unmodified letters of the Latin alphabet. The Latvian alphabet lacks Q, W, X and Y. These letters are not used in Latvian for writing foreign personal and geographical names; instead they are adapted to Latvian phonology, orthography, and morphology, e. g. Džordžs Volkers Bušs (George Walker Bush). However, these four letters can be used in mathematics and sometimes in brand names: their names are kū, dubult vē, iks and igrek. The Latvian alphabet has a further eleven letters formed by adding diacritic marks to some letters. The vowel letters A, E, I and U can take a macron to show length, unmodified letters being short. The letters C, S and Z, which in unmodified form are pronounced [ts], [s] and [z] respectively, can be marked with a caron. These marked letters, Č, Š and Ž are pronounced [tʃ], [ʃ] and [ʒ] respectively. The letters Ģ, Ķ, Ļ and Ņ are written with a cedilla or a small comma placed below (or, in the case of the lowercase g, above). They are modified (palatalized) versions of G, K, L and N and represent the sounds [ɟ], [c], [ʎ] and [ɲ]. Non-standard varieties of Latvian add extra letters to this standard set.

The letters F and H appear only in loanwords.[2]

Historically the letters CH, Ō and Ŗ were also used in the Latvian alphabet. The last of these stood for the palatalized dental trill /rʲ/ which is still used in some dialects (mainly outside Latvia) but not in the standard language, and hence the letter Ŗ was removed from the alphabet on 5 June 1946, when the Latvian SSR legislature passed a regulation that officially replaced it with R in print.[3] Similar reforms replacing CH with H, and Ō with O, were enacted over the next few years.

The letters CH, Ō and Ŗ continue to be used in print throughout most of the Latvian diaspora communities, whose founding members left their homeland before the post-World War II Soviet-era language reforms. An example of a publication in Latvia today, albeit one aimed at the Latvian diaspora, that uses the older orthography—including the letters CH, Ō and Ŗ—is the weekly newspaper Brīvā Latvija.

Sound–spelling correspondences

Latvian has a phonetic spelling. There are only a few exceptions to this:

- The first is the letter E and its long variation Ē, which are used to write two sounds that represent the short and long versions of either [ɛ] or [æ] respectively: ēdu (/ɛː/, I ate) vs. ēdu (/æː/, I eat) and dzer (/ɛ/, 2sg, you eat) vs. dzer (/æ/, 3sg, s/he eats)

- The letter O indicates both the short and long [ɔ], and the diphthong [uɔ̯]. These three sounds are written as O, Ō and Uo in Latgalian, and some Latvians campaign for the adoption of this system in standard Latvian. However, the majority of Latvian linguists argue that o and ō are found only in loanwords, with the Uo sound being the only native Latvian phoneme. The digraph Uo was discarded in 1914, and the letter Ō has not been used in the standard orthography since 1946. Example: robots [o] (a robot, noun) vs. robots [uo] (toothed; adjective); tols [o] (tolite; noun) vs tols [uo] (hornless; adjective).

- Also, Latvian orthography does not distinguish intonation homographs: sējums [ē] (crops) vs sējums [è] (book edition), tā (that, feminine) vs tā (this way, adverb).

- Some spellings based on morphology exist.[4]

Latvian orthography also uses digraphs Dz, Dž and Ie.

| Grapheme | IPA | English approximation |

|---|---|---|

| a | ɑ | like father, but shorter |

| ā | ɑː | car |

| e | e | elephant |

| æ | map | |

| ē | eː | similar to play |

| æː | like bad, but longer | |

| i | i | Between it and eat |

| ī | iː | each |

| o | [uɔ̯̯] | tour (some dialects) |

| o | not (some dialects) | |

| oː | though; boat | |

| u | u | between look and Luke |

| ū | uː | you |

| Grapheme | IPA | English approximation |

|---|---|---|

| b | b | brother |

| c | t̪͡s̪ | like cats, with the tongue touching the teeth |

| č | t͡ʃ | chair |

| d | d̪ | like door, with the tongue touching the teeth |

| dz | d̪͡z̪ | like lids, with the tongue touching the teeth |

| dž | d͡ʒ | jog |

| f | f | finger |

| g | ɡ | gap |

| ģ | ɟ | between duty (without yod-dropping) and argue |

| h | x | loch (Scottish English) |

| j | j | yawn |

| k | k | cat |

| ķ | c | similar to skew |

| l | l | lamp |

| ļ | ʎ | similar to William |

| m | m | male |

| n | n̪, ŋ | like nail, with the tongue touching the teeth, or sing |

| ņ | ɲ | jalapeño |

| p | p | peace |

| r | r, [rʲ] | rolled r, like Spanish perro or Scottish English curd |

| s | s̪ | like sock, with the tongue touching the teeth |

| š | ʃ | shadow |

| t | t̪ | like table, with the tongue touching the teeth |

| v | v | vacuum |

| z | z̪ | like zebra, with the tongue touching the teeth |

| ž | ʒ | vision |

Old orthography

The old orthography was based on that of German and did not represent the Latvian language phonemically. At the beginning it was used to write religious texts for German priests to help them in their work with Latvians. The first writings in Latvian were chaotic: there were as many as twelve variations of writing Š. In 1631 the German priest Georg Mancelius tried to systematize the writing. He wrote long vowels according to their position in the word — a short vowel followed by h for a radical vowel, a short vowel in the suffix and vowel with a diacritic mark in the ending indicating two different accents. Consonants were written following the example of German with multiple letters. The old orthography was used until the 20th century when it was slowly replaced by the modern orthography.

Computer encoding

Lack of software support of diacritics has caused an unofficial style of orthography, often called translit, to emerge for use in situations when the user is unable to access Latvian diacritic marks on the computer or using cell phone. It uses only letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet, and letters not used in standard orthography are usually omitted. In this style, diacritics are replaced by digraphs:

- ā, ē, ī, ū - aa, ee, ii, uu

- ļ, ņ, ģ, ķ - lj, nj, gj, kj

- š - sh (as well as ss, sj, etc.)

Some people may find it difficult to use such methods and either write without any indication of missing diacritic marks or use digraphs only if the diacritic mark in question would make a semantic difference.[5] There is yet another style, sometimes called "Pokémonism" (In Latvian Internet slang "Pokémon" is derogatory for adolescent), characterised by use of some elements of leet, use of non-Latvian letters (particularly w and x instead of v and ks), use of c instead of ts, use of z in endings, and use of mixed case.

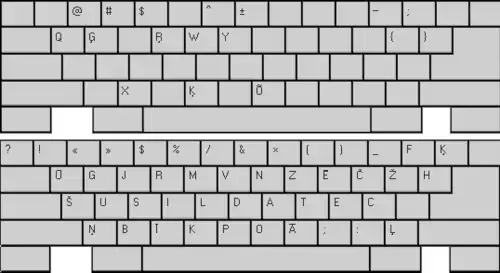

Keyboard

Standard QWERTY keyboards are used for writing in Latvian; diacritics are entered by using a dead key (usually ', occasionally ~). Some keyboard layouts use a modifier key AltGr (most notable of such is the Windows 2000 and XP built-in layout (Latvian QWERTY)). In the early 1990s, the Latvian ergonomic keyboard layout was developed. Although this layout may be available with language support software, it has not become popular because of a lack of keyboards with such a configuration.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Latvian alphabet. |

- "Vēsture" (in Latvian). Latvian Language Agency. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- Praulinš, Dace (2012). "2.3 Consonants - Līdzskaņi". Latvian: An Essential Grammar. Routledge. ISBN 9781136345364. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- LPSR AP Prezidija Ziņotājs, no. 132 (1946), p. 132.

- Praulinš, Dace (2012). "2.4 Sound changes - Skaņu parmaņas". Latvian: An Essential Grammar. Routledge. ISBN 9781136345364. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- Veinberga, Linda (2001). "Latviešu valodas izmaiņas un funkcijas interneta vidē" (in Latvian). politika.lv. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2007.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)