Noah's Ark

Noah's Ark (Hebrew: תיבת נח; Biblical Hebrew: Tevat Noaḥ)[Notes 1] is the vessel in the Genesis flood narrative (Genesis chapters 6–9) through which God spares Noah, his family, and examples of all the world's animals from a world-engulfing flood.[1] The story in Genesis is repeated, with variations, in the Quran, where the Ark appears as Safina Nūḥ (Arabic: سفينة نوح "Noah's boat").

Searches for Noah's Ark have been made from at least the time of Eusebius (c. 275–339 CE), and believers in the Ark continue to search for it in modern times. Many searches have been mounted for the Ark, but no confirmable physical proof of the Ark has ever been found.[2] There is no scientific evidence that Noah's Ark existed as it is described in the Bible.[3] There is also no evidence of a global flood, and most scientists agree that it would be impossible.[4] Some researchers believe that a real (though localized) flood event in the Middle East could potentially have inspired the oral and later written narratives from Genesis; a Black Sea Deluge 7500 years ago has been proposed as such a historical candidate.[5][6]

Description

The structure of the Ark (and the chronology of the flood) are homologous with the Jewish Temple and with Temple worship.[7] Accordingly, Noah's instructions are given to him by God (Genesis 6:14–16): the ark is to be 300 cubits long, 50 cubits wide, and 30 cubits high (approximately 134×22×13 m or 440×72×43 ft).[8] These dimensions are based on a numerological preoccupation with the number sixty, the same number characterizing the vessel of the Babylonian flood-hero.[1] Its three internal divisions reflect the three-part universe imagined by the ancient Israelites: heaven, the earth, and the underworld.[9] Each deck is the same height as the Temple in Jerusalem, itself a microcosmic model of the universe, and each is three times the area of the court of the tabernacle, leading to the suggestion that the author saw both Ark and tabernacle as serving for the preservation of human life.[10][11] It has a door in the side, and a tsohar, which may be either a roof or a skylight.[8] It is to be made of Gopher wood, a word which appears nowhere else in the Bible - and divided into qinnim, a word which always refers to birds' nests elsewhere in the Bible, leading some scholars to emend this to qanim, reeds.[12] The finished vessel is to be smeared with koper, meaning pitch or bitumen: in Hebrew the two words are closely related, kaparta ("smeared") ... bakopper.[12]

Origins

Mesopotamian precursors

For well over a century, scholars have recognized that the Bible's story of Noah's Ark is based on older Mesopotamian models.[13] Because all these flood stories deal with events that allegedly happened at the dawn of history, they give the impression that the myths themselves must come from very primitive origins, but the myth of the global flood that destroys all life only begins to appear in the Old Babylonian period (20th–16th centuries BCE).[14] The reasons for this emergence of the typical Mesopotamian flood myth may have been bound up with the specific circumstances of the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE and the restoration of order by the First Dynasty of Isin.[15]

There are nine known versions of the Mesopotamian flood story, each more or less adapted from an earlier version. In the oldest version, inscribed in the Sumerian city of Nippur c.1600 BCE, the hero is King Ziusudra. This story is known as the Sumerian Flood Story and probably derives from an earlier version. The Ziusudra version tells how he builds a boat and rescues life when the gods decide to destroy it. This basic plot is common in several subsequent flood-stories and heroes, including Noah. Ziusudra's Sumerian name means "He of long life." In Babylonian versions, his name is Atrahasis, but the meaning is the same. In the Atrahasis version, the flood is a river flood.[16]:20–27

The version closest to the biblical story of Noah, as well as its most likely source, is that of Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh.[17] A complete text of Utnapishtim's story is a clay tablet dating from the 7th century BCE, but fragments of the story have been found from as far back as the 19th-century BCE.[17] The last known version of the Mesopotamian flood story was written in Greek in the 3rd century BCE by a Babylonian priest named Berossus. From the fragments that survive, it seems little changed from the versions of two thousand years before.[18]

The parallels between Noah's Ark and the arks of Babylonian flood-heroes Atrahasis and Utnapishtim have often been noted. Atrahasis' Ark was circular, resembling an enormous quffa, with one or two decks.[19] Utnapishtim's ark was a cube with six decks of seven compartments, each divided into nine subcompartments (63 subcompartments per deck, 378 total). Noah's Ark was rectangular with three decks. There is believed to be a progression from a circular to a cubic or square to rectangular. The most striking similarity is the near-identical deck areas of the three arks: 14,400 cubits2, 14,400 cubits2, and 15,000 cubits2 for Atrahasis, Utnapishtim, and Noah, only 4% different. Professor Finkel concluded that "the iconic story of the Flood, Noah, and the Ark as we know it today certainly originated in the landscape of ancient Mesopotamia, modern Iraq."[20]

Linguistic parallels between Noah's and Atrahasis' arks have also been noted. The word used for "pitch" (sealing tar or resin) in Genesis is not the normal Hebrew word, but is closely related to the word used in the Babylonian story.[21] Likewise, the Hebrew word for "ark" (tevah) is nearly identical to the Babylonian word for an oblong boat (ṭubbû), especially given that "v" and "b" are the same letter in Hebrew: bet (ב).[20]

However, the causes for God or the gods sending the flood differ in the various stories. In the Hebrew myth, the flood inflicts God's judgment on wicked humanity. The Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh gives no reasons, and the flood appears the result of divine caprice.[22] In the Babylonian Atrahasis version, the flood is sent to reduce human overpopulation, and after the flood, other measures were introduced to limit humanity.[23][24][25]

Composition

There is consensus among scholars that the Torah (the first five books of the Bible, beginning with Genesis) was the product of a long and complicated process that was not completed until after the Babylonian exile.[26] Biblical scholar Richard Friedman suggests that the Flood narrative was composed by the combination of two versions of the story, characterized by the names "God" and "Yahweh".[27]

In later works

Rabbinic Judaism

The myth of the flood closely parallels the story of the creation: a cycle of creation, un-creation, and re-creation, in which the Ark plays a pivotal role.[28] The universe as conceived by the ancient Hebrews comprised a flat disk-shaped earth with the heavens above and Sheol, the underworld of the dead, below.[29] These three were surrounded by a watery "ocean" of chaos, protected by the firmament, a transparent but solid dome resting on the mountains which ringed the earth.[29] Noah's three-deck Ark represents this three-level Hebrew cosmos in miniature: heavens, earth, and waters beneath.[30] In Genesis 1, God created the three-level world as a space in the midst of the waters for humanity; in Genesis 6–8, God re-floods that space, saving only Noah, his family, and the animals in the Ark.[28]

The Talmudic tractates Sanhedrin, Avodah Zarah, and Zevahim relate that, while Noah was building the Ark, he attempted to warn his neighbors of the coming deluge, but was ignored or mocked. God placed lions and other ferocious animals to protect Noah and his family from the wicked who tried to keep them from the Ark. According to one Midrash, it was God, or the angels, who gathered the animals and their food to the Ark. As there had been no need to distinguish between clean and unclean animals before this time, the clean animals made themselves known by kneeling before Noah as they entered the Ark. A differing opinion is that the Ark itself distinguished clean animals from unclean, admitting seven pairs each of the former and one pair each of the latter.

According to Sanhedrin 108b, Noah was engaged both day and night in feeding and caring for the animals, and did not sleep for the entire year aboard the Ark.[31] The animals were the best of their kind and behaved with utmost goodness. They did not procreate so that the number of creatures that disembarked was exactly equal to the number that embarked. The raven created problems, refusing to leave the Ark when Noah sent it forth and accusing the patriarch of wishing to destroy its race, but as the commentators pointed out, God wished to save the raven, for its descendants were destined to feed the prophet Elijah.

According to one tradition, refuse was stored on the lowest of the Ark's three decks, humans and clean beasts on the second, and the unclean animals and birds on the top; a differing interpretation described the refuse as being stored on the topmost deck, from where it was shoveled into the sea through a trapdoor. Precious stones, as bright as the noon sun, provided light, and God ensured the food remained fresh.[32][33][34] In an unorthodox interpretation, the 12th-century Jewish commentator Abraham ibn Ezra interpreted the ark as a vessel that remained underwater for 40 days, after which it floated to the surface.[35]

Christianity

Interpretations of the ark narrative played an essential role in early Christian doctrine. The First Epistle of Peter (composed around the end of the first century AD[36]) compared Noah's salvation through water to Christian salvation through baptism.[1Pt 3:20–21]

St. Hippolytus of Rome (died 235) sought to demonstrate that "the Ark was a symbol of the Christ who was expected", stating that the vessel had its door on the east side—the direction from which Christ would appear at the Second Coming—and that the bones of Adam were brought aboard, together with gold, frankincense, and myrrh (the symbols of the Nativity of Christ). Hippolytus furthermore stated that the Ark floated to and fro in the four directions on the waters, making the sign of the cross, before eventually landing on Mount Kardu "in the east, in the land of the sons of Raban, and the Orientals call it Mount Godash; the Armenians call it Ararat".[37] On a more practical plane, Hippolytus explained that the lowest of the three decks was for wild beasts, the middle for birds and domestic animals, and the top for humans. He says male animals were separated from females by sharp stakes to prevent breeding.[37]

The early Church Father and theologian Origen (c. 182–251), in response to a critic who doubted that the Ark could contain all the animals in the world, argued that Moses, the traditional author of the book of Genesis, had been brought up in Egypt and would therefore have used the larger Egyptian cubit. He also fixed the shape of the Ark as a truncated pyramid, square at its base, and tapering to a square peak one cubit on a side; it was not until the 12th century that it came to be thought of as a rectangular box with a sloping roof.[38]

Early Christian artists depicted Noah standing in a small box on the waves, symbolizing God saving the Christian Church in its turbulent early years. St. Augustine of Hippo (354–430), in his work City of God, demonstrated that the dimensions of the Ark corresponded to the dimensions of the human body, which according to Christian doctrine is the body of Christ and in turn the body of the Church.[39] St. Jerome (c. 347–420) identified the raven, which was sent forth and did not return, as the "foul bird of wickedness" expelled by baptism;[40] more enduringly, the dove and olive branch came to symbolize the Holy Spirit and the hope of salvation and eventually, peace.[41] The olive branch remains a secular and religious symbol of peace today.

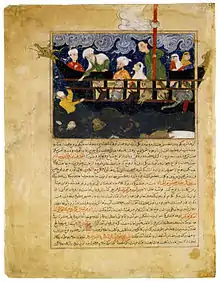

The Quran and later Muslim works

In contrast to the Jewish tradition, which uses a term that can be translated as a "box" or "chest" to describe the Ark, surah 29:15 of the Quran refers to it as a safina, an ordinary ship, and surah 54:13 describes the Ark as "a thing of boards and nails". Abd Allah ibn Abbas, a contemporary of Muhammad, wrote that Noah was in doubt as to what shape to make the Ark and that Allah revealed to him that it was to be shaped like a bird's belly and fashioned of teak wood.[42]

Abdallah ibn 'Umar al-Baidawi, writing in the 13th century, explains that in the first of its three levels, wild and domesticated animals were lodged, in the second human beings, and the third birds. On every plank was the name of a prophet. Three missing planks, symbolizing three prophets, were brought from Egypt by Og, son of Anak, the only one of the giants permitted to survive the flood. The body of Adam was carried in the middle to divide the men from the women. Surah 11:41 says: "And he said, 'Ride ye in it; in the Name of Allah it moves and stays!'"; this was taken to mean that Noah said, "In the Name of Allah!" when he wished the Ark to move, and the same when he wished it to stand still.

The medieval scholar Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn al-Husayn Masudi (died 956) wrote that Allah commanded the Earth to absorb the water, and certain portions which were slow in obeying received salt water in punishment and so became dry and arid. The water which was not absorbed formed the seas, so that the waters of the flood still exist. Masudi says the ark began its voyage at Kufa in central Iraq and sailed to Mecca, circling the Kaaba before finally traveling to Mount Judi, which surah 11:44 gives as its final resting place. This mountain is identified by tradition with a hill near the town of Jazirat ibn Umar on the east bank of the Tigris in the province of Mosul in northern Iraq, and Masudi says that the spot could be seen in his time.[32][33]

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith regards the Ark and the Flood as symbolic.[43] In Baháʼí belief, only Noah's followers were spiritually alive, preserved in the "ark" of his teachings, as others were spiritually dead.[44][45] The Baháʼí scripture Kitáb-i-Íqán endorses the Islamic belief that Noah had numerous companions on the ark, either 40 or 72, as well as his family, and that he taught for 950 (symbolic) years before the flood.[46] The Baháʼí Faith was founded in 19th century Persia, and it recognizes divine messengers from both the Abrahamic and the Indian traditions.

Historicity

Research shows a literal Noah's Ark could not be practical.[3] Considering that, of course, a global flood would be impossible,[47] some researchers propose that sufficiently large floods could have been the basis of the myth, specifically as oral histories that were then written into scriptures. One such proposed candidate is the Black Sea deluge, caused by the connection of the Mediterranean Sea and the Black Sea through the Bosphorous strait 7500 years ago.[5][6] Underwater archeological evidence of pre-greek civilizations seems to support this hypothesis.[48]

The first edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica from 1771 describes the Ark as factual. It also attempts to explain how the Ark could house all living animal types: "... Buteo and Kircher have proved geometrically, that, taking the common cubit as a foot and a half, the ark was abundantly sufficient for all the animals supposed to be lodged in it ... the number of species of animals will be found much less than is generally imagined, not amounting to a hundred species of quadrupeds".[49] It also endorses a supernatural explanation for the flood, stating that "many attempts have been made to account for the deluge by means of natural causes: but these attempts have only tended to discredit philosophy, and to render their authors ridiculous".[50]

The 1860 edition attempts to solve the problem of the Ark being unable to house all animal types by suggesting a local flood, which is described in the 1910 edition as part of a "gradual surrender of attempts to square scientific facts with a literal interpretation of the Bible" that resulted in "the 'higher criticism' and the rise of the modern scientific views as to the origin of species" leading to "scientific comparative mythology" as the frame in which Noah's Ark was interpreted by 1875.[51]

Ark's geometry

In Europe, the Renaissance saw much speculation on the nature of the Ark that might have seemed familiar to early theologians such as Origen and Augustine. At the same time, however, a new class of scholarship arose, one which, while never questioning the literal truth of the ark story, began to speculate on the practical workings of Noah's vessel from within a purely naturalistic framework. In the 15th century, Alfonso Tostada gave a detailed account of the logistics of the Ark, down to arrangements for the disposal of dung and the circulation of fresh air. The 16th-century geometer Johannes Buteo calculated the ship's internal dimensions, allowing room for Noah's grinding mills and smokeless ovens, a model widely adopted by other commentators.[41]

Searches for Noah's Ark

Searches for Noah's Ark have been made from at least the time of Eusebius (c.275–339 CE) to the present day. Today, the practice is widely regarded as pseudoarchaeology.[53][2][54] Various locations for the ark have been suggested but have never been confirmed.[55][56] Search sites have included Durupınar site, a site on Mount Tendürek in eastern Turkey and Mount Ararat, but geological investigation of possible remains of the ark has only shown natural sedimentary formations.[57]

See also

- Biblical literalism

- Black Sea deluge hypothesis

- Book of Noah

- Dwyfan and Dwyfach

- Gilgamesh flood myth

- List of longest wooden ships

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

- Manu (Hinduism)

- Noah's Ark replicas and derivatives

- Sons of Noah

- Sumerian flood myth

- TalkOrigins Archive

- Wives aboard Noah's Ark

- Ziusudra

Notes

- The word "ark" in modern English comes from Old English aerca, meaning a chest or box.(See Cresswell 2010, p.22) The Hebrew word for the vessel, teva, occurs twice in the Torah, in the flood narrative (Book of Genesis 6-9) and in the Book of Exodus, where it refers to the basket in which Jochebed places the infant Moses. (The word for the Ark of the Covenant is quite different). The Ark is built to save Noah, his family, and representatives of all animals from a divinely-sent flood intended to wipe out all life, and in both cases, the teva has a connection with salvation from waters. (See Levenson 2014, p.21)

References

Citations

- Bailey 1990, p. 63.

- Cline, Eric H. (2009). Biblical Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199741076. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Moore, Robert A. (1983). "The Impossible Voyage of Noah's Ark". Creation Evolution Journal. 4 (1): 1–43. Archived from the original on 2016-07-17. Retrieved 2016-07-10.

- Lorence G. Collins (2009). "Yes, Noah's Flood May Have Happened, But Not Over the Whole Earth". NCSE. Archived from the original on 2018-06-26. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- Ryan, W. B. F.; Pitman, W. C.; Major, C. O.; Shimkus, K.; Moskalenko, V.; Jones, G. A.; Dimitrov, P.; Gorür, N.; Sakinç, M. (1997). "An abrupt drowning of the Black Sea shelf" (PDF). Marine Geology. 138 (1–2): 119–126. Bibcode:1997MGeol.138..119R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.598.2866. doi:10.1016/s0025-3227(97)00007-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-12-23.

- Ryan, W. B.; Major, C. O.; Lericolais, G.; Goldstein, S. L. (2003). "Catastrophic flooding of the Black Sea". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 31 (1): 525−554. Bibcode:2003AREPS..31..525R. doi:10.1146/annurev.earth.31.100901.141249.

- Blenkinsopp 2011, p. 139.

- Hamilton 1990, pp. 280–281.

- Kessler & Duerloo 2004, p. 81.

- Wenham 2003, p. 44.

- Batto 1992, p. 95.

- Hamilton 1990, pp. 281.

- Kvanvig 2011, p. 210.

- Chen 2013, p. 3-4.

- Chen 2013, p. 253.

- Cline, Eric H. (2007). From Eden to Exile: Unraveling Mysteries of the Bible. National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0084-7.

- Nigosian 2004, p. 40.

- Finkel 2014, p. 89-101.

- "Nova: Secrets of Noah's Ark". www.pbs.org. October 7, 2015. Retrieved 2020-05-17.

- Finkel 2014, chpt.14.

- McKeown 2008, p. 55.

- May, Herbert G., and Bruce M. Metzger. The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. 1977.

- Stephanie Dalley, ed., Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others Archived 2016-04-24 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 5–8.

- Alan Dundes, ed., The Flood Myth Archived 2016-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 61–71.

- J. David Pleins, When the Great Abyss Opened: Classic and Contemporary Readings of Noah's Flood Archived 2016-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 102–103.

- Enns 2012, p. 23.

- Richard Elliot Friedman (1997 ed.), Who Wrote the Bible, p. 51.

- Gooder 2005, p. 38.

- Knight 1990, pp. 175–176.

- Kessler & Deurloo 2004, p. 81.

- Avigdor Nebenzahl, Tiku Bachodesh Shofer: Thoughts for Rosh Hashanah, Feldheim Publishers, 1997, p. 208.

- McCurdy, J. F.; Bacher, W.; Seligsohn, M.; et al., eds. (1906). "Noah". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com.

- McCurdy, J. F.; Jastrow, M. W.; Ginzberg, L.; et al., eds. (1906). "Ark of Noah". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com.

- Hirsch, E. G.; Muss-Arnolt, W.; Hirschfeld, H., eds. (1906). "The Flood". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com.

- Ibn Ezra's Commentary to Genesis 7:16 Archived 2013-05-24 at the Wayback Machine. HebrewBooks.org.

- The Early Christian World, Volume 1, p.148, Philip Esler

- Hippolytus. "Fragments from the Scriptural Commentaries of Hippolytus". New Advent. Archived from the original on 17 April 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- Cohn 1996, p. 38.

- St. Augustin (1890) [c. 400]. "Chapter 26:That the Ark Which Noah Was Ordered to Make Figures In Every Respect Christ and the Church". In Schaff, Philip (ed.). Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers [St. Augustin's City of God and Christian Doctrine]. 1. 2. The Christian Literature Publishing Company.

- Jerome (1892) [c. 347–420]. "Letter LXIX. To Oceanus.". In Schaff, P (ed.). Niocene and Post-Niocene Fathers: The Principal Works of St. Jerome. 2. 6. The Christian Literature Publishing Company.

- Cohn 1996

- Baring-Gould, Sabine (1884). "Noah". Legends of the Patriarchs and Prophets and Other Old Testament Characters from Various Sources. James B. Millar and Co., New York. p. 113.

- From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, 28 October 1949: Baháʼí News, No. 228, February 1950, p. 4. Republished in Compilation 1983, p. 508

- Poirier, Brent. "The Kitab-i-Iqan: The key to unsealing the mysteries of the Holy Bible". Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- Shoghi Effendi (1971). Messages to the Baháʼí World, 1950–1957. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Baháʼí Publishing Trust. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-87743-036-0. Archived from the original on 2008-10-23. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- From a letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi to an individual believer, 25 November 1950. Published in Compilation 1983, p. 494

- Dyken, JJ (2013). The Divine Default. Algora Publishing. Archived from the original on 2016-07-01. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- Radford, Tim (14 September 2000). "Evidence found of Noah's Ark flood victims". The Guardian.

- "Ark". Encyclopædia Britannica. 1. Edinburgh: Society of Gentlemen in Scotland. 1771. Archived from the original on 2018-08-05. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- "Deluge". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2. Edinburgh: Society of Gentlemen in Scotland. 1771. Archived from the original on 2018-08-05. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- "Ark". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 Slice 5. Ark: Horace Everett Hooper. 1910. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- "Cameo with Noah's Ark". The Walters Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- Fagan, Brian M.; Beck, Charlotte (1996). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195076189. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Feder, Kenneth L. (2010). Encyclopedia of Dubious Archaeology: From Atlantis to the Walam Olum. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313379192. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- Mayell, Hillary (27 April 2004). "Noah's Ark Found? Turkey Expedition Planned for Summer". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- Stefan Lovgren (2004). Noah's Ark Quest Dead in Water Archived 2012-01-25 at the Wayback Machine – National Geographic

- Collins, Lorence G. (2011). "A supposed cast of Noah's ark in eastern Turkey" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Lloyd R. (1990). "Ark". Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780865543737.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008), Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible (4th ed.), Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning, pp. 61–63, ISBN 978-0495391050

- Best, Robert (1999), Noah's Ark And the Ziusudra Epic, ISBN 978-09667840-1-5

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011), Creation, Un-creation, Re-creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11, A&C Black, ISBN 9780567372871

- Chen, Y.S. (2013), The Primeval Flood Catastrophe: Origins and Early Development in Mesopotamian Traditions, OUP Oxford, ISBN 9780199676200

- Cohn, Norman (1996). Noah's Flood: The Genesis Story in Western Thought. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06823-8.

- Cotter, David W. (2003). Genesis. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814650400.

- Cresswell, Julia (2010). "Ark". Oxford Dictionary of Word Origins. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199547937.

- Enns, Peter (2012), The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn't Say about Human Origins, Baker Books, ISBN 9781587433153

- Evans, Gwen (3 February 2009). "Reason or Faith? Darwin Expert Reflects". UW-Madison News. University of Wisconsin-Madison. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Finkel, Irving L. (2014), The Ark Before Noah: Decoding the Story of the Flood, Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 9781444757071

- Gooder, Paula (2005). The Pentateuch: A Story of Beginnings. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567084187.

- Hamilton, Victor P. (1990). The book of Genesis: Chapters 1–17. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825216.

- Kessler, Martin; Deurloo, Karel Adriaan (2004). A commentary on Genesis: The Book of Beginnings. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809142057.

- Knight, Douglas A. (1990). "Cosmology". In Watson E. Mills (General Editor) (ed.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-402-4.

- Kvanvig, Helge (2011), Primeval History: Babylonian, Biblical, and Enochic: An Intertextual Reading, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004163805

- Levenson, Jon D. (2014). "Genesis: introduction and annotations". In Berlin, Adele; Brettler, Marc Zvi (eds.). The Jewish Study Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199393879.

- McKeown, James (2008). Genesis. Two Horizons Old Testament Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-8028-2705-0.

- Isaak, M. (1998). "Problems with a Global Flood". TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

Isaak no a geologist

- Isaak, Mark (5 November 2006). "Index to Creationist Claims, Geology". TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Lippsett, Lonny (2009). "Noah's Not-so-big Flood: New evidence rebuts controversial theory of Black Sea deluge". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- Morton, Glenn (17 February 2001). "The Geologic Column and its Implications for the Flood". TalkOrigins Archive. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

Morton Not a Geologist

- Nigosian, S.A. (2004), From Ancient Writings to Sacred Texts: The Old Testament and Apocrypha, JHU Press, ISBN 9780801879883

- Numbers, Ronald L. (2006). The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design, Expanded Edition. Harvard University Press. pp. 624. ISBN 978-0-674-02339-0.

- Parkinson, William (January–February 2004). "Questioning 'Flood Geology': Decisive New Evidence to End an Old Debate". NCSE Reports. 24 (1). Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Schadewald, Robert J. (Summer 1982). "Six Flood Arguments Creationists Can't Answer". Creation/Evolution Journal. 3 (3): 12–17. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

- Schadewald, Robert (1986). "Scientific Creationism and Error". Creation/Evolution. 6 (1): 1–9. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- Scott, Eugenie C. (January–February 2003), My Favorite Pseudoscience, 23

- Stewart, Melville Y. (2010). Science and Religion in Dialogue. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4051-8921-7.

- Wenham, Gordon (2003). "Genesis". In James D. G. Dunn; John William Rogerson (eds.). Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Young, Davis A. (1995). The Biblical Flood: A Case Study of the Church's Response to Extrabiblical Evidence. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8028-0719-9. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Young, Davis A.; Stearley, Ralph F. (2008). The Bible, Rocks, and Time: Geological Evidence for the Age of the Earth. Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Academic. ISBN 978-0-8308-2876-0.

Further reading

Commentaries on Genesis

- Towner, Wayne Sibley (2001). Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664252564.

- Von Rad, Gerhard (1972). Genesis: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664227456.

- Whybray, R. N. (2001). "Genesis". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

General

- Batto, Bernard Frank (1992). Slaying the Dragon: Mythmaking in the Biblical Tradition. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664253530.

- Browne, Janet (1983). The Secular Ark: Studies in the History of Biogeography. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 276. ISBN 978-0-300-02460-9.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). Reverberations of Faith: a Theological Handbook of Old Testament Themes. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664222314.

- Campbell, Antony F.; O'Brien, Mark A. (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413670.

Sources of the bible.

- Carr, David M. (1996). Reading the Fractures of Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664220716.

- Clines, David A. (1997). The Theme of the Pentateuch. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567431967.

- Davies, G. I. (1998). "Introduction to the Pentateuch". In John Barton (ed.). Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Douglas, J. D.; Tenney, Merrill C., eds. (2011). Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. revised by Moisés Silva (Revised ed.). Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310229834.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). The Old Testament between theology and history: a critical survey. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.

- Levin, Christoph L. (2005). The Old testament: A Brief Introduction. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691113944.

The Old testament: a brief introduction Christoph Levin.

- Levin, C. (2005). The Old Testament: A Brief Introduction. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691113944.

- Longman, Tremper (2005). How to Read Genesis. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830875603.

- McEntire, Mark (2008). Struggling with God: An Introduction to the Pentateuch. Mercer University Press. ISBN 9780881461015.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to Reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Van Seters, John (1992). Prologue to History: The Yahwist As Historian in Genesis. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664221799.

- Van Seters, John (1998). "The Pentateuch". In Steven L. McKenzie; Matt Patrick Graham (eds.). The Hebrew Bible Today: An Introduction to Critical Issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Van Seters, John (2004). The Pentateuch: A Social-science Commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 9780567080882.

- Walsh, Jerome T. (2001). Style and Structure in Biblical Hebrew Narrative. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658970.

- Bailey, Lloyd R. (1989). Noah, the Person and the Story. South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-87249-637-8.

- Campbell, Antony F.; O'Brien, Mark A. (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413670.

Sources of the bible.

- Campbell, A. F.; O'Brien, M. A. (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: Texts, Introductions, Annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413670.

- Best, Robert M. (1999). Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic. Fort Myers, Florida: Enlil Press. ISBN 978-0-9667840-1-5.

- Compilation (1983). Hornby, Helen (ed.). Lights of Guidance: A Baháʼí Reference File. Baháʼí Publishing Trust, New Delhi, India. ISBN 978-81-85091-46-4.

- Dalrymple, G. Brent (1991). The Age of the Earth. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2331-2.

- Emerton, J. A. (1988). Joosten, J. (ed.). "An Examination of Some Attempts to Defend the Unity of the Flood Narrative in Genesis: Part II". Vetus Testamentum. XXXVIII (1).

- Nicholson, Ernest W. (2003). The Pentateuch in the Twentieth Century: the legacy of Julius Wellhausen. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199257836.

- Plimer, Ian (1994). Telling Lies for God: Reason vs Creationism. Random House Australia. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-09-182852-3.

- Speiser, E. A. (1964). Genesis. The Anchor Bible. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-00854-9.

- Tigay, Jeffrey H. (1982). The Evolution of the Gilgamesh Epic. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. ISBN 0865165467.

- Van Seters, John (2004). The Pentateuch: A Social-Science commentary. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0567080889.

- Wenham, Gordon (1994). "The Coherence of the Flood Narrative". In Hess, Richard S.; Tsumura, David Toshio (eds.). I Studied Inscriptions From Before the Flood (Google Books)

|format=requires|url=(help). Sources for Biblical and Theological Study. 4. Eisenbrauns. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-931464-88-1. - Young, Davis A. (March 1995). The Biblical Flood: A Case Study of the Church's Response to Extrabiblical Evidence. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Pub Co. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-8028-0719-9.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about "Noah's Ark". |

Media related to Noah's Ark at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Noah's Ark at Wikimedia Commons