Paleontology in the United States

Paleontology in the United States refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the United States. Paleontologists have found that at the start of the Paleozoic era, what is now "North" America was actually in the southern hemisphere. Marine life flourished in the country's many seas. Later the seas were largely replaced by swamps, home to amphibians and early reptiles. When the continents had assembled into Pangaea drier conditions prevailed. The evolutionary precursors to mammals dominated the country until a mass extinction event ended their reign.

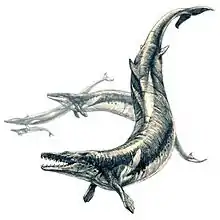

The Mesozoic era followed and the dinosaurs began their rise to dominance, spreading into the country before Pangaea split up. During the latter Jurassic Morrison Formation dinosaurs lived in the western states. During the Cretaceous, the Gulf of Mexico expanded until it split North America in half. Plesiosaurs and mosasaurs swam in its waters. Later it began to withdraw and the western states were home to the Hell Creek dinosaurs. Another mass extinction ended the reign of the dinosaurs.

The Cenozoic era began afterward. The inland sea of the Cretaceous vanished and mammals came to dominate the land. The western states were home to primitive camels and horses as well as the carnivorous creodonts. Soon mammals had entered the oceans and the early whale Basilosaurus swam the coastal waters of the southeast. Rhino-like titanotheres dominated Oligocene South Dakota. From this point on the climate in the United States cooled until the Pleistocene, when glaciers spread. Saber-toothed cats, woolly mammoths, mastodons, and dire wolves roamed the land. Humans arrived across a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska and may have played a role in hunting these animals into extinction.

Native Americans have been familiar with fossils for thousands of years, but the first major fossil discovery to attract the attention of formally trained scientists were the Ice Age fossils of Kentucky's Big Bone Lick. These fossils were studied by eminent intellectuals like France's George Cuvier and local statesmen like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington. By the beginning of the 19th century, Dinosaur footprints were discovered near the country's east coast. Later in the century, as more dinosaur fossils were uncovered, eminent paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh were embroiled in a bitter rivalry to collect the most fossils and name the most new species.

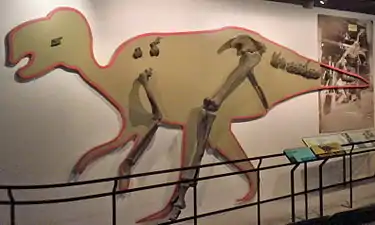

Early in the 20th century major finds continued, such as the Ice Age mammals of the La Brea Tar Pits. Mid-to-late twentieth-century discoveries in the United States triggered the Dinosaur Renaissance as the discovery of the bird-like Deinonychus overturned misguided notions of dinosaurs as plodding lizard-like animals, highlighting their sophisticated physiology and apparent relationship with birds. Other notable finds in the United States include Maiasaura, which provided early evidence for parental care in dinosaurs and "Seismosaurus", the largest known dinosaur.

Prehistory

Paleontologists have found that during the Precambrian, the areas now composing the United States were home to the first known eucaryotes, whose remains were preserved in California. Other simple Precambrian life is known from Michigan,[1] while more complex forms in Arizona[2] and North Carolina.[3]

During the Cambrian, the land masses now composing the United States were separate and located in the southern hemisphere.[4] Trilobites are the most characteristic animal of the time,[5] and are especially abundant in Utah.[6] Ordovician America was still home to a wide variety of marine invertebrates. An important fauna was preserved in the states of Indiana, Kentucky, and Ohio in the Cincinnati region.[7] Life in Silurian America was especially diverse around the coral reefs of Indiana.[8] It was also the time of New York's famous sea scorpion, Eurypterus.[9] Fishes diversified greatly during the Devonian.[10] On land the first known seed plants appeared in Pennsylvania and some of the world's first forests appeared in New York.[11] Mississippian America was once more covered in seas,[12] now notably home to abundant crinoids.[13] During the Pennsylvanian America was largely terrestrial[14] and vast swamps expanded across the country[15] which were home to amphibians.[16] Reptiles were appearing around this time.[17] Into the Permian the continents had collided uniting into a single supercontinent called Pangaea. Much of the country was dry.[18] Precursors to mammals like Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus lived in Texas.[19] At the end of the Permian the largest mass extinction in earth's history occurred, killing some 96% of species on the planet.[18]

During the Triassic, the Mesozoic era began.[20] Ichthyosaurs entered the sea and achieved large sizes in Nevada.[21] The Petrified Forest appeared in the southwest.[22] The dinosaurs appeared and achieved dominance on land[23] while pterosaurs flew overhead.[24] Into the Jurassic, plesiosaurs began usurping marine dominance from the ichthyosaurs.[25] Dinosaurs continued to diversify on land and increase in size.[26] A vast complex of floodplains covered the western United States[27] that was home to iconic creatures like Allosaurus,[28] Apatosaurus,[29] Ceratosaurus,[30] and Stegosaurus.[31] During the Early Cretaceous dinosaur faunas began to change.[32] Around the same time sea levels began to gradually rise and the Gulf of Mexico extended up into Alaska, dividing North America in two.[33] This formed the Western Interior Seaway,[34] where ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs gradually gave way to mosasaurs.[35] Overhead pterosaurs like Pteranodon of Kansas achieved vast wingspans.[36] Before the end of the Cretaceous the seaway began to retreat and the coastal plains of Montana and the Dakotas were home to iconic dinosaurs like Edmontosaurus, Triceratops, and Tyrannosaurus rex.[37] Soon however, the marine reptiles, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs that dominated the planet went extinct, likely because a meteor impact destabilized the planet's ecosystems.[38]

After the extinction of the dominant reptile groups, the Cenozoic[39] ushered in the Age of Mammals.[40] Sea levels continued to decline[41] until the vast Western Interior Seaway was reduced to a small inland body in North Dakota.[42] Mammals were beginning to diversify and dominate the land.[40] The creodonts, forerunners of modern carnivores, arose to prominence during the Paleocene.[43] During the Eocene the western states were home to small primitive camels[44] and horses.[45] Over time both groups got larger and lost several toes.[44][45] Even by the late Eocene mammals had entered the oceans and the great primitive whale Basilosaurus swam in the coastal waters of the southeastern states like Alabama[46] and Mississippi.[47] Rhino-like titanotheres dominated the South Dakota badlands of the Oligocene.[48] From this point on the climate in the United States cooled[41] until the iconic Ice Age mammals of the Pleistocene like saber-toothed cats, woolly mammoths, mastodons and dire wolves[49] spread across the continent in advance of glaciers.[50] Humans arrived across a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska[51] and may have played a role in hunting these animal into extinction.[52]

History

Native Americans have been familiar with fossils for thousands of years.[53] They both told myths[54] about them and applied them to practical purposes.[55] The idea of powerful natural forces contending for balance is a common motif in fossil-influenced Native American folklore.[54] Practical applications for fossils in Native American cultures include ingestion as medicine[56] and use in food preparation.[55] African slaves also contributed their knowledge to the early study of paleontology in the United States. The first reasonably accurate recorded identification of vertebrate fossils in the new world was made by slaves on a South Carolina plantation who recognized the elephant affinities of mammoth molars uncovered there in 1725.[57] However, the first major fossil discovery to attract the attention of formally trained scientists were the Ice Age fossils of Kentucky's Big Bone Lick.[58] These fossils were studied by eminent intellectuals like France's George Cuvier and local statesmen and frontiersman like Daniel Boone,[59] Benjamin Franklin,[60] William Henry Harrison,[61] Thomas Jefferson,[62] and George Washington.[63] They triggered controversy regarding the idea that entire species of animals could become extinct.[64] By the end of the 18th century possible dinosaur fossils might already have been found in New Jersey.[65]

By the beginning of the 19th century, their fossil footprints definitely had been found in Massachusetts[66] and later, Connecticut.[67] These tracks were researched by the Reverend Edward Hitchcock and instrumental to the establishment of ichnology, the study of trace fossils, as a science.[66] During the late 1850s, the world's first reasonably complete dinosaur skeleton was discovered in New Jersey.[68] Joseph Leidy would name it Hadrosaurus. This was the first known dinosaur, the first dinosaur to be interpreted as two-legged, and the first to be mounted for exhibition in a museum.[69] Later in the century Edward Drinker Cope described a new carnivorous dinosaur from New Jersey he called Laelaps. When he gave fellow paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh a tour of the quarry the fossils were taken from Marsh secretly convinced Cope's workers to send fossils to himself instead. Marsh also learned that the name Laelaps had already been used for a different animal and renamed Cope's dinosaur Dryptosaurus out from under him. This instigated a bitter rivalry to collect the most fossils and name the most new prehistoric species that took the two paleontologists and their crews deep into the west looking for fossils and attempting to undermine each other's fieldwork.[70]

Early in the 20th century major finds continued, like the Ice Age mammals of the La Brea Tar Pits, which preserved hundreds of thousands fossils in central Los Angeles.[71] The South Dakota School of Mines and Technology uncovered vast Oligocene bonebeds in the South Dakota badlands.[72] Seven years later, another bonebed was discovered in New Mexico, that preserved hundreds of the dinosaur Coelophysis.[73] During the 1960s, John Ostrom led an expedition into Montana that uncovered the remains of the nimble, bird-like carnivorous dinosaur Deinonychus. Based on this find, Ostrom and his student, Robert Bakker began arguing that dinosaurs had sophisticated physiologies and were even the ancestors of modern birds. These ideas revolutionized dinosaur paleontology through a period called the Dinosaur Renaissance.[74] Another notable 20th-century find occurred in Montana during the 1970s. Jack Horner and Bob Makela's new duck-billed dinosaur genus Maiasaura provided both the first known dinosaur nests in North America as well as early evidence that dinosaurs provided parental care for their young, unlike most reptiles.[75] During the early 1990s, the new genus "Seismosaurus" was put forward as a candidate for the largest known dinosaur.[76]

Geographic divisions

Official symbols

Official fossils

Official dinosaurs

- Colorado: Stegosaurus

- Maryland: Astrodon johnstoni

- Missouri: Hypsibema missouriensis

- New Jersey: Hadrosaurus foulkii

- Texas: Pleurocoelus (1997-2009) Paluxysaurus jonesi (2009-)

- Washington, D.C.: Capitalsaurus

- Wyoming: Triceratops

Official rocks or stones

Some state rocks or stones are also fossils.

- Florida: Agatized coral

- Michigan: Petoskey stone

- Mississippi: Petrified wood

- Texas: Petrified palmwood

Official gems

Some state gems are also fossils.

- Washington: Petrified wood

- West Virginia Lithostrotionella

Protected areas

- Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska

- Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park, Nebraska

- Big Bone Lick State Park, Kentucky

- Dinosaur National Monument, Utah

- Dinosaur State Park and Arboretum, Connecticut

- Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado

- Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming

- Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Idaho

- John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon

- Mississippi Petrified Forest, Mississippi

- Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

- Rockford Iowa Fossil and Prairie Park, Iowa

- Trammel Fossil Park, Ohio

- Windley Key Fossil Reef Geological State Park, Florida

People

Natural history museums

Footnotes

- Murray (1974); "Michigan", page 157.

- Murray (1974); "Arizona", page 93.

- Huntsman, Kelley, Scotchmoor, and Springer (2004); "Paleontology and geology".

- Thompson (1982); "Cambrian Period", page 42.

- Thompson (1982); "Trilobites:", page 43.

- Murray (1974); "Utah", page 273.

- Thompson (1982); "Invertebrate Life:", pages 45-46.

- Indiana Geological Survey; "Indiana's Reef Rocks", page 1.

- Tetlie (2007); "Table 3", page 560.

- Thompson (1982); "First Jawed Fishes:", pages 51-52.

- Thompson (1982); "Seed Plants:", page 53.

- Thompson (1982); "Mississippian Period", page 54.

- Thompson (1982); "Age of Crinoids:", page 54.

- Thompson (1982); "Pennsylvanian Period", page 56.

- Thompson (1982); "Coal Swamps:", pages 56-57.

- Thompson (1982); "Terrestrial Vertebrates:", page 57.

- Thompson (1982); "First Reptiles:", page 57.

- Thompson (1982); "Permian Period", page 58.

- Murray (1974); "Texas", page 270.

- Thompson (1982); "Triassic Period", page 63.

- Thompson (1982); "Ichthyosaurs:", page 65.

- Thompson (1982); "Land Plants:", page 64.

- Thompson (1982); "Dinosaurs:", pages 64-65.

- Unwin (2006); "An Ever-Changing World", page 21.

- Thompson (1982); "Marine Reptiles:", page 69.

- Thompson (1982); "Land Reptiles:", page 69.

- Foster (2007); "Wild World of the Jurassic: The Setting", page 11.

- Foster (2007); "Allosaurus fragilis", page 170.

- Foster (2007); "Apatosaurus ajax", page 194.

- Foster (2007); "Ceratosaurus", page 166.

- Foster (2007); "Stegosaurus", pages 211-212.

- Thompson (1982); "Dinosaurs:", page 74.

- Everhart (2005); "One Day in the Life of a Mosasaur", page 5.

- Everhart (2005); "One Day in the Life of a Mosasaur", page 6.

- Thompson (1982); "Dinosaurs:", pages 73-74.

- Everhart (2005); "Peteranodons: Rulers of the Air", page 194.

- Horner (2001); "Latest Cretaceous Time: Maastrichtian Stage", page 77.

- Thompson (1982); "Mass Extinction:", page 75.

- Thompson (1982); "Tertiary Period", page 77.

- Thompson (1982); "Age of Mammals", page 79.

- Thompson (1982); "Sea Level and Climate:", page 77.

- Murray (1974); "North Dakota", page 224.

- Thompson (1982); "Carnivores:", page 81.

- Thompson (1982); "Camels:", page 80.

- Thompson (1982); "First Horses:", page 79.

- Murray (1974); "Alabama", page 86.

- Murray (1974); "Mississippi", page 171.

- Thompson (1982); "Titanotheres:", page 80.

- Thompson (1982); "Migrations of Mammals:", pages 84-85.

- Thompson (1982); "Glaciation:", page 82.

- Thompson (1982); "Humans in North America:", page 84.

- Thompson (1982); "Large Mammal Extinctions:", page 85.

- Mayor (2005); "Water Monsters and Thunder Birds on the Prairie and in the Badlands", page 272.

- Mayor (2005); "Preface", page xxxv.

- Mayor (2005); "Water Monsters and Thunder Birds on the Prairie and in the Badlands", page 273.

- Mayor (2005); "Cultural and Historical Conflicts", page 299.

- Mayor (2005); "Thomas Jefferson's Paleontological Inquiries", page 56.

- Mayor (2005); "Introduction: Marsh Monsters of Big Bone Lick", pages 1-2.

- Hedeen (2008); "Animal Incognitum", page 51.

- Hedeen (2008); "Animal Incognitum", page 46.

- Hedeen (2008); "A Question of Tusks", page 76.

- Hedeen (2008); "Thomas Jefferson Takes an Interest", page 65.

- Hedeen (2008); "Thomas Jefferson Takes an Interest", page 57.

- Hedeen (2008); "Animal Incognitum", pages 50-51.

- Weishampel and Young (1996); "Early American Bones", pages 56-57.

- Weishampel and Young (1996); "Footprints in Stone", page 58.

- Murray (1974); "Connecticut", page 112.

- Weishampel and Young (1996); "Haddonfield Hadrosaurus", page 68.

- Weishampel and Young (1996); "Haddonfield Hadrosaurus", pages 69-71.

- Weishampel and Young (1996); "Marsh and Cope", pages 75-76.

- Murray (1974); "California", page 98.

- Murray (1974); "South Dakota", page 256.

- Jacobs (1995); "Chapter 2: The Original Homestead", page 40.

- Horner (2001); "History of Dinosaur Collecting in Montana", pages 53-54.

- Horner (2001); "History of Dinosaur Collecting in Montana", page 56.

- Foster (2007); "The Earth-Shaker Lizard and a New Mexico Renaissance", page 116.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in the United States. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleontology in the United States |

- Everhart, Michael J. Oceans Of Kansas: A Natural History Of The Western Interior Sea (Life of the Past). Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005. 322 pp.

- Foster, J. (2007). Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp. ISBN 978-0-253-34870-8.

- Gangloff, Roland, Sarah Rieboldt, Judy Scotchmoor, Dale Springer. July 21, 2006. "Alaska, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Hedeen, S., 2008, Big Bone Lick: the Cradle of American Paleontology: Lexington, Kentucky, The University Press of Kentucky, 182 p.

- Horner, John R. Dinosaurs Under the Big Sky. Mountain Press Publishing Company. 2001. ISBN 0-87842-445-8.

- Huntsman, John, Patricia Kelley, Judy Scotchmoor, Dale Springer. February 17, 2004. "North Carolina, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- "Indiana's Reef Rocks". GeoNotes. Indiana Geological Survey.

- Jacobs, L. L., III. 1995. Lone Star Dinosaurs. Texas A&M University Press.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian. 1974. Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. 348 pp.

- O. Erik Tetlie (2007). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Elsevier. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011. ISSN 0031-0182. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2011. Retrieved May 20, 2011.

- Thompson, Ida (1982). National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Fossils. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 846. ISBN 0-394-52412-8.

- Unwin, David M. (2006). The Pterosaurs: From Deep Time. New York: Pi Press. ISBN 0-13-146308-X.

- Weishampel, D.B. & L. Young. 1996. Dinosaurs of the East Coast. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

_-_Mauricio_Ant%C3%B3n.jpg.webp)