Political divisions of Spain

The political division of the Kingdom of Spain is defined in Part VIII of the Spanish constitution of 1978, which establishes three levels of territorial organization: municipalities, provinces and autonomous communities,[1] the first group constituting the subdivisions of the second, and the second group constituting the subdivisions of the last. The State[2] guarantees the realization of the principle of solidarity by endeavouring to establish an economic balance between the different areas of the Spanish territory.[2]

.svg.png.webp) |

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Spain |

The autonomous communities were constituted by exercising the right to autonomy or self-government that the constitution guarantees to the nationalities and regions of Spain,[3] while declaring the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation.[4] The autonomous communities enjoy a highly decentralized form of territorial organization, but based on devolution, and thus Spain is not a federation,[5] since the State is superior to the communities and retains full sovereignty.[5] In the absence of an explicit definition in the constitution the Constitutional Court of Spain has labeled this model of territorial organization the "State of Autonomous Communities", to avoid implying any particular model.[5]

Autonomous communities and autonomous cities

The autonomous communities (comunidades autónomas in Spanish and Galician, comunitats autònomes in Catalan, autonomia erkidego in Basque) constitute the first order (highest) level of territorial organization of Spain. They were created progressively after the promulgation of the Spanish constitution in 1978, to the "nationalities and regions" that constitute the Spanish nation by the exercise of the right to self-government by:[6]

- two or more adjacent provinces with common historical, cultural and economic characteristics,

- insular territories, and

- a single province with a historical regional identity.

The constitution allowed two exceptions to the above set of criteria, namely that the Spanish Parliament reserves the right to:[7]

- authorize, in the nation's interest, the constitution of an autonomous community even if it is a single province without a historical regional identity (which allowed for the creation of the Community of Madrid, which had been part of the historical region of Castile–La Mancha); and to

- authorize or grant autonomy to entities or territories that are not provinces (which allowed for the creation of two autonomous cities, Spanish exclaves in North Africa).

Even though the provinces were the basis for the creation of the autonomous communities, these roughly follow the lines of the old kingdoms and regions of the Iberian peninsula prior to unification.[8]

Originally autonomy was to be granted only to the so-called "historical nationalities":[9] Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia, regions with strong regional identities[10] that had been granted self-government or had approved a Statute of Autonomy during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1936).

While the constitution was still being drafted, and self-government seemed likely to be granted only to the "historical nationalities", there was a popular outcry in Andalusia, demanding self-government as well, which led to the creation of a quicker process for that region, which eventually self-identified as a "historical nationality" as well. In the end, the right to self-government was extended to any other region that wanted it.[10]

The "historical nationalities" were to be granted autonomy through a rapid and simplified process, whereas the rest of the regions had to follow specific requirements set forth in the constitution. Between 1979 and 1983, all regions in Spain chose to be constituted as autonomous communities; four additional communities self-identify as "nationalities", albeit acceding to autonomy via the longer process set forth in the constitution.

While the constitution did not establish how many autonomous communities were to be created, on 31 July 1981, Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo, then the prime minister of Spain and Felipe González, leader of the opposition in Parliament, signed the "First Autonomic Pacts" (Primeros pactos autonómicos in Spanish), in which they agreed to the creation of 17 autonomous communities and two autonomous cities, with the same institutions of government, but different competences.[11] By 1983, all 17 autonomous communities were constituted: Andalusia, Aragon, Asturias, the Balearic Islands, the Basque Country, the Canary Islands, Cantabria, Castile and León, Castile–La Mancha, Catalonia, the Community of Madrid, Extremadura, Galicia, La Rioja, Navarra, the Region of Murcia and the Valencian Community. The two autonomous cities, Ceuta and Melilla were constituted in 1995.

Autonomous communities have a wide range of powers, but the devolution of power to the individual communities has been asymmetrical.[10] The Constitutional Court has declared that the autonomous communities are characterized both by their homogeneity and diversity.[5] Autonomous communities are "equal" in their subordination to the constitutional order, in their representation in the Senate of Spain, and in the sense that their differences should not imply any economical or social privilege from the others. Nonetheless, they differ in the process whereby they acceded to autonomy and their range of competences.[5] The cases of the Basque Country and Navarra are exceptional in that the medieval charters (fueros in Spanish) that had granted them fiscal autonomy were retained, or rather "updated"; the rest of the autonomous communities do not enjoy fiscal autonomy.

All autonomous communities have a parliamentary form of government. The institutions of government of the different autonomous communities (i.e. the Parliament or the Office of the Executive) may have names peculiar to the community. For example, the set of government institutions in Catalonia and the Valencian Community are known as the Generalitat, the Parliament of Asturias is known as the Junta General (lit. General Gathering or Assembly), whereas Xunta in Galicia is the denomination of the office of the executive, otherwise known simply as the "Government".

The official names of the autonomous communities can be in Spanish only (which applies to the majority of them), in the co-official language in the community only (as in the Valencian Community and the Balearic Islands), or in both Spanish and the co-official language (as in the Basque Country, Navarre and Galicia). Since 2006, Occitan—in its Aranese dialect—is also a co-official language in Catalonia, making it the only autonomous community whose name has three official variants (Spanish: Cataluña, Catalan: Catalunya, Occitan: Catalonha).

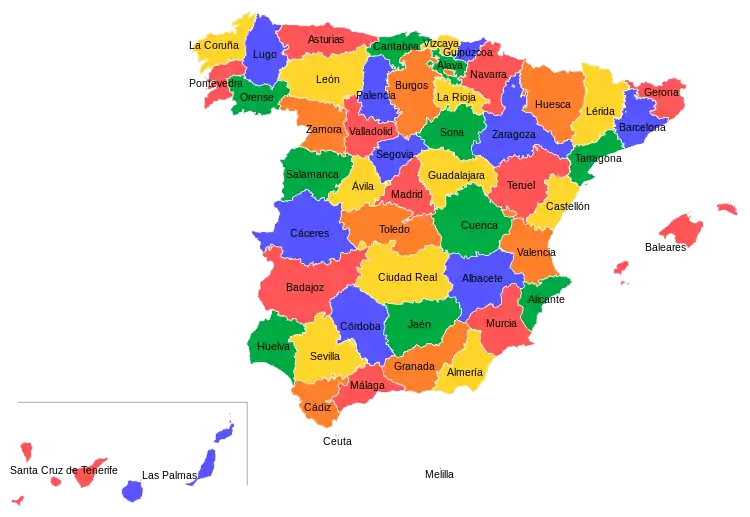

Provinces

The provinces (provincias in Spanish and Galician, províncies in Catalan, probintziak in Basque) are the second-level territorial and administrative divisions of Spain. The provincial scheme was created in 1833 by Javier de Burgos and based upon the limits of the old Hispanic kingdoms, though dividing them, if necessary, due to geographic and/or demographic reasons (i.e. to ensure a relative homogeneity in size and population).

This scheme has undergone only minor adjustments since 1833, most notably the division of the Canary Islands into two provinces in 1927. There are fifty provinces in Spain.

The province is a local entity with legal personality constituted by the aggregations of municipalities. The governance of provinces is carried out by Provincial Deputations or Councils, with the following exceptions:

- those autonomous communities consisting of a single province, in which case, the institutions of government of the autonomous community replace those of the province;

- the Basque Country, in which the provinces are constituted as "historical territories" (territorios históricos in Spanish, foru lurraldeak or lurralde historikoak in Basque), in which "Chartered Deputations" (Diputaciones Forales in Spanish, Foru aldundiak in Basque) are in charge of both the political and fiscal administration of the territories; and

- the insular communities, that is, the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands, in which each island or group of islands is governed by "Insular Deputations" (Diputación insular in Spanish) or "Insular Councils" (Consejo insular in Spanish, Consell Insular in Catalan).

The responsibilities of the provinces vary amongst the autonomous communities they belong to. Since the creation of the autonomous communities their scope of action is minimal, with the exception of the historical territories of the Basque Country. In all cases, they are guaranteed a legal status and autonomy to conduct their internal administration by the constitution.

The official names of the provinces can be in Spanish, the co-official language of the community they belong to, or both.

Municipalities

The municipalities of Spain (municipios or concejos[12] in Spanish, concellos in Galician, municipis in Catalan, udalerriak in Basque),[13] constitute the lowest level of territorial organization in the country, and are guaranteed a measure of autonomy by the constitution.[14] The administration of the municipalities corresponds to the ayuntamientos (ayuntamientos in Spanish, concellos in Galician, ajuntament in Catalan, udalak in Basque) consisting of mayors and councillors, who are elected by universal suffrage.[14]

The municipalities are the basic entities of the territorial organization of the State, the immediate channels of the citizens' participation in public affairs.[15] The official names of the municipalities of Spain can be in Spanish—the official language of the country, in any of the co-official languages of the autonomous communities they belong to, if applicable, or in both.[15]

All citizens of Spain are required to register in the municipality they live in, and after doing so, they are juridically considered "neighbors" (residents) of the municipality, a designation that grants them various rights and privileges, and which entail certain obligations as well, including the right to vote or be elected for public office in said municipality.[15] The right to vote in municipal elections is extended to Spanish citizens living abroad. A Spaniard abroad, upon registering in a consulate, has the right to vote in the local elections of the last municipality they resided in. A Spanish citizen born abroad must choose between the last municipality his or her mother or father last lived in.

Other territorial entities

The autonomous communities have the right to establish additional territorial entities in their internal territorial organizations, without eliminating the provinces or the municipalities (even if the latter can have a different name). Catalonia had created two types of additional territorial entities: the comarques and the vegueries, both of which had administrative powers and were initially recognized in the last Statute of Autonomy (organic law) of the community, but The Constitutional Court annulled, among others, the parts that modified the territorial organization. Almost all communities have defined territorial entities (e.g. comarcas or merindades), but these do not have administrative powers and are simply geographic or historical designations.

One special case of such territorial entities is Western Sahara, formerly the colony of Spanish Sahara up to 1976,[16] is disputed between Morocco, which controls 80% of the territory and administers it as an integral part of its national territory, and the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, which controls and administers the remaining 20% as the "Liberated territories". The United Nations, however still considers Spain to be the administrating state of the whole territory,[17] under the Non-Self-Governing Territories awaiting the outcome of the ongoing Manhasset negotiations and resulting election to be overseen by the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara.

Spanish Micronesia

The islands (Kapingamarangi, Nukuoro, Mapia, Rongrik and Ulithi) would still remain in Spanish possession because they were not transferred to the United States after the war of 1898 or to Germany in 1899.

This hypothesis was born on March 5, 1948 when the Spanish lawyer and researcher of the CSIC Emilio Pastor y Santos wrote a letter denouncing the possibility that three naval stations were established by Spain in the Carolinas, Marianas and Palau Islands, according to art. 31 of the Spanish-German treaty of 1899. Convinced of his discovery, he asks for the concession of facilities in Saipan, Yap and Koror. Months later, in October, he opened a second front and "denounced" that there were four islands left in the area in which sovereignty belongs to Spain, because they forgot to include them in the German-Spanish treaty of 1899. In 1950 he published the book Territories of Spanish sovereignty in Oceania with its investigations. On January 12, 1949, the question of the sovereignty of these islands was discussed in a Council of Ministers chaired by Franco but, as stated in it: [1]

... that while the matter is not clarified, it is appropriate to wait before carrying out any action with the United States or with the friendly powers that are part of the UN, since Spain does not have contacts with the UN and it would be this that would have to resolve on the final fate of those islands of Micronesia that belonged to Japan.

However, an opinion of January 4, 1949 from the legal advisory office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs “estimated that any hypothetical right of Spain over said islands would have been destroyed by subsequent trust regimes, which were those that occurred after World War I. with the transfer of said territories to Japan and after World War II with its attribution to the United States ". [2]

In 2014, the Government settled all speculation about the maintenance of Spanish possessions in the Pacific by means of a parliamentary response to a deputy. In his opinion, Spain ceded all the remaining places in that ocean in 1899. [2] [3] It adds that “traditionally these islands had been linked to the Carolinas and it had to be understood that if those were ceded, these were also transferred "[2] and" the Spanish attitude between 1899 and 1948 shows that the intention of Spain when signing the treaty with Germany was to transfer all its possessions in the Pacific to it "[2] and" it would also be inconsistent that Spain he would have wanted to cede the Carolinas, Palau and Marianas, but he would have reserved sovereignty over a few islets of little economic value over which he had never exercised his de facto sovereignty », [2] so he settles all speculation on the maintenance of Spanish possessions in the Pacific, concluding that Spain does not retain the sovereignty of any island in the Pacific. [2]

Mapia is currently under the sovereignty of Indonesia; Kapingamarangi, Ulithi and Nukuoro under the sovereignty of the Federated States of Micronesia and Rongerik is under the control of the Marshall Islands.

chincha islands

After the war in 1864 the return to Peru was not transferred by any treaty

References

- Article 137 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

- Article 138 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

- Article 143 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

- Article 2 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

- Sinópsis del artículo 137 de la Constitución Española de 1978. Congreso de los Diputados

- Part VIII, Third Chapter, Article 143

- Article 144 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

- Spain. (2008). In The Columbia Encyclopedia. Accessed 1 June 2011

- "Regional Government". Spain. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Accessed 10 December 2007

- Federalism and the Balance of Power in European States (2006), Michael Keating for the OECD

- Aparicio, Sonia. Los Pactos Autonómicos. El Mundo. España

- In Asturias, municipalities are known as "councils" (concejos in Spanish, conceyos in Asturian language). Other autonomous communities may also have consejos as territorial divisions which, however, do not correspond to municipalities

- Spanish is the official language of Spain. Galician, Catalan and Basque are coofficial in specific communities. Catalan is officially and statutorily designated as Valencian in the Valencian Community

- Article 140 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978

- Ley 7/1985, de 2 de abril, Reguladora de las Bases del Régimen Local art.11

- CIA's The World Factbook entry for Western Sahara: "Western Sahara is a disputed territory on the northwest coast of Africa bordered by Morocco, Mauritania, and Algeria. After Spain withdrew from its former colony of Spanish Sahara in 1976, Morocco annexed the northern two-thirds of Western Sahara and claimed the rest of the territory in 1979, following Mauritania's withdrawal"

- UN General Assembly Resolution 34/37 and UN General Assembly Resolution 35/19