Prehistoric Iberia

The prehistory of the Iberian Peninsula begins with the arrival of the first hominins 1.2 million years ago and ends with the arrival of the Phoenicians, when the territory enters the domains of written history. In this long period, some of its most significant landmarks were to host the last stand of the Neanderthal people, to develop some of the most impressive Paleolithic art, alongside southern France, to be the seat of the earliest civilizations of Western Europe and finally to become a most desired colonial objective due to its strategic position and its many mineral riches.

-Museo_Arqueol%C3%B3gico_Nacional.jpg.webp)

Lower and Middle Paleolithic

Hominin inhabitation of the Iberian Peninsula dates from the Paleolithic.[1] Early hominin remains have been discovered at a number of sites on the peninsula. Significant evidence of an extended occupation of Iberia by Neanderthal man has also been discovered. Homo sapiens first entered Iberia towards the end of the Paleolithic. For a time Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted until the former were finally driven to extinction. Modern man continued to inhabit the peninsula through the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods.

Many of the best preserved prehistoric remains are in the Atapuerca region, rich with limestone caves that have preserved a million years of human evolution. Among these sites is the cave of Gran Dolina, where six hominin skeletons, dated between 780,000 and 1.2 million years ago, were found in 1994. Experts have debated whether these skeletons belong to the species Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, or a new species called Homo antecessor. In the Gran Dolina, investigators have found evidence of tool use to butcher animals and other hominins, which is likely to constitute the first evidence of cannibalism in a hominin species. Evidence of fire has also been found at the site, suggesting they cooked their meat.

Also in Atapuerca, is the site at Sima de los Huesos, or "Pit of Bones". Excavators have found the remains of 30 hominins dated to about 400,000 years ago. The remains have been tentatively classified as Homo heidelbergensis and may be ancestors of the Neanderthals. No evidence of habitation has been found at the site except for one stone hand-ax, and all of the remains at the site are of young adults or teenagers. The age similarity suggests the remains were not the result of accidents. The seemingly deliberate placement of remains and lack of habitation may mean that the bodies were deliberately interred in the pit as a place of burial, which would make the site the first evidence of hominin burial.

Around 200,000 BC, during the Lower Paleolithic period, Neanderthals first entered the Iberian Peninsula. Around 70,000 BC, during the Middle Paleolithic period the last ice age began and the Neanderthal Mousterian culture was established. The Escoural Cave has evidence of human activity starting in the Middle Palaeolithic,[2] with an estimated date of 50,000 years BP.[3] Around 35,000 BC, during the Upper Paleolithic, the Neanderthal Châtelperronian cultural period began. Emanating from Southern France this culture extended into Northern Iberia. This culture continued to exist until around 28,000 BC when Neanderthal man faced extinction, their final refuge has been said to be Gibraltar.[4]

Neanderthal remains have been found at a number of sites on the Iberian Peninsula. A Neanderthal skull was found in Forbes' Quarry in Gibraltar in 1848 making it the second territory after Belgium where remains of Neanderthals were found. Neanderthals were not recognized as a separate species until the discovery of remains in Neandertal, Germany in 1856, though their classification as a separate species has recently been called into question.[5] Subsequent Neanderthal discoveries in Gibraltar have also been made including the skull of a four-year-old child[6] and preserved excrement on top of baked mussel shells.

The Neanderthals were present in Iberia until at least 28,000 or 27,000 BC. Evidence of their presence in this period is found in Columbeira, Figueira Brava and Salemas.[7] The Cave of Salemas and the Cave of Pego do Diabo, both located in Loures Municipality, were inhabited in the Paleolithic.[8] Archaeological industries of the Middle Paleolithic in Iberia lasted until about 28,000 or 26,000 BC. During this period, the Mousterian culture was replaced by the Aurignacian culture. The Mousterian culture is associated with Neanderthals and the Aurignacian culture is associated with modern humans.[9]

In Zafarraya a Neanderthal mandible and Mousterian tools, associated with the Neanderthal culture, were found in 1995. The mandible was dated to about 28,000 BC and the tools to about 25,000 BC. These dates make the Zafarraya remains the youngest evidence of Neanderthals and have expanded the timeline of Neanderthal existence. The more recent dating of the remains also provides the first evidence for prolonged co-existence between Neanderthals and modern man. L'Arbreda Cave in Catalonia contains Aurignacian cave paintings, as well as earlier remains from Neanderthals. Some have also suggested that the newer remains in Iberia suggest Neanderthals were driven out of Central Europe by modern man to the Iberian peninsula where they sought refuge.

Upper Paleolithic

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Spain |

|

| Timeline |

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Portugal |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Gibraltar |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Early Upper Paleolithic

The Chatelperronian culture (typically associated with Neanderthal man) is found in the Cantabrian region and in Catalonia.

The Aurignacian culture (work of Homo sapiens) succeeds it and has the following periodization:[10]

- Archaic Aurignacian: found in Cantabria (Morín and El Pendo caves), where it alternates with Chatelperronian, and in Catalonia. The carbon-14 (14

C) dates for Morín cave are relatively late in the European context: c. 28,500 BP, but the occupation dates for El Pendo (where it's older than Chatelperronian layers) must be of earlier date. - Typical Aurignacian: is found in Cantabria (Morín, El Pendo, Castillo), the Basque Country (Santimamiñe) and Catalonia. Radiocarbon dating gives the following dates: 32,425 and 29,515 BP.

- Evolved Aurignacian: is found in Cantabria (Morin, El Pendo, El Otero, Hornos de la Peña), Asturias (El Cierro, El Conde) and Catalonia.

- Final Aurignacian: in Cantabria (El Pendo), after the Gravettian interlude.

In the Mediterranean area (south of the Ebro), Aurignacian remains have been found sparsely distributed in the Lands of Valencia (Les Mallaetes) and Murcia (Las Pereneras) and Andalusia (Higuerón), as far west as Gibraltar (Gorham's Cave). The 14

C dates available are: 29,100 BP (Les Mallaetes), 28,700 and 27,860 BP (Gorham's Cave).

The remains of a child dated to ca. 24,500 years BP,[11] known as the Lapedo child, were discovered in Lagar Velho, in Leiria Municipality. The cranium, mandible, dentition and postcrania present a mosaic of European early modern human and Neanderthal features.[11] It is claimed the individual was a hybrid between a Cro-Magnon and a Neanderthal. This claim is contested.[12] Ian Tattersall and Jeffrey H. Schwartz consider it is probable the individual was a modern human, part of the Gravettian culture.[7]

Gravettian

The Gravettian culture followed the steps of the Aurignacian expansion but its remains are not very abundant in the Cantabrian area (north), while in the southern region they are more common.

In the Cantabrian area all Gravettian remains belong to late evolved phases and are found always mixed with Aurignacian technology. The main sites are found in the Basque Country (Lezetxiki, Bolinkoba), Cantabria (Morín, El Pendo, El Castillo) and Asturias (Cueto de la Mina). It is archeologically divide in two phases characterized by the amount of Gravettian elements: the phase A has a 14

C date of c.20,710 BP and the phase B is of later date.

The Cantabrian Gravettian has been paralleled to the Perigordian V-VII of the French sequence. It eventually vanishes from the archaeological sequence and is replaced by an "Aurignacian renaissance", at least in El Pendo cave. It is considered "intrusive", in contrast with the Mediterranean area, where it probably means a real colonization.[10]

In the Mediterranean region, the Gravettian culture also had a late arrival. Nevertheless, the south-east has an important number of sites of this culture, especially in the Land of Valencia (Les Mallaetes, Parpaló, Barranc Blanc, Meravelles, Coba del Sol, Ratlla del Musol, Beneito). It is also found in the Land of Murcia (Palomas, Palomarico, Morote) and Andalusia (Los Borceguillos, Zájara II, Serrón, Gorham's Cave).

The first indications of modern human colonization of the interior and the west of the peninsula are found only in this cultural phase, with a few late Gravettian elements found in the Manzanares valley (Madrid) and Salemas cave (Alentejo, Portugal).

Solutrean

The Solutrean culture shows its earliest appearances in Laugerie Haute (Dordogne, France) and Les Mallaetes (Land of Valencia), with radiocarbon dates of 21,710 and 20,890 BP respectively.[10] In the Iberian peninsula it shows three different facies:

The Iberian (or Mediterranean) facies is defined by the sites of Parpalló and Les Mallaetes in the province of Valencia. They are found immersed in important Gravettian perdurations that would eventually redefine the facies as "Gravettizing Solutrean."[10] The archetypical sequence, that of Parpalló and Les Mallaetes caves, is:

- Initial Solutrean.

- Full or Middle Solutrean, dated in its lower layers to 20,180 BP.

- A sterile layer with signs of intense cold that is related to the Last Glacial Maximum.

- Upper or Evolved Solutrean, including bone tools and also needles of this material.

These two caves are surrounded by many other sites (Barranc Blanc, Meravelles, Rates Penaes, etc.) that show only a limited impact of Solutrean and instead have many Gravettian perdurations, showing a convergence that has been named as "Gravetto-Solutrean".

Solutrean is also found in the Land of Murcia, Mediterranean Andalusia and the lower Tagus (Portugal). In the Portuguese case there are no signs of Gravettization.

The Cantabrian facies shows two markedly different tendencies in Asturias and the Vasco-Cantabrian area. The oldest findings are all in Asturias and lack of the initial phases, beginning with the full Solutrean in Las Caldas (Asturias) and other nearby sites, followed by evolved Solutrean, with many unique regional elements. Radiocarbon dates oscillate between 20,970 and 19,000 BP.[10]

In the Vasco-Cantabrian area instead the Gravettian influences seem persistent and the typical Solutrean foliaceous elements are minority. Some transitional elements that prelude the Magdalenian, like the monobiselated bone spear point, are already present. Most important sites are Altamira, Morín, Chufín, Salitre, Ermittia, Atxura, Lezetxiki, and Santimamiñe.

In northern Catalonia there is an early local Solutrean, followed by scarce middle elements but with a well-developed final Solutrean. It is related to the French Pyrenean sequences. Main sites are Cau le Goges, Reclau Viver and L'Arbreda.

In the region of Madrid there were some findings attributed to Solutrean that are today missing.

Late Upper Paleolithic

This phase is defined by the Magdalenian culture, even if in the Mediterranean area the Gravettian influence is still persistent.

In the Cantabrian area, the early Magdalenian phases show two different facies: the "Castillo facies" evolves locally over final Solutrean layers, while the "Rascaño facies" appears in most cases directly over the natural soil (no earlier occupations of these sites).

In the second phase, the lower evolved Magdalenian, there are also two facies but now with a geographical divide: the "El Juyo facies" is found in Asturias and Cantabria, while the "Basque Country facies" is only found in this region.

The dates for this early Magdalenian period oscillate between 16,433 BP for Rascaño cave (Rascaño facies), 15,988 and 15,179 BP for the same cave (El Juyo facies) and 15,000 BP for Altamira (Castillo facies). For the Basque Country facies the cave of abauntz has given 15,800 BP.[10]

The middle Magdalenian shows less abundance of findings.

The upper Magdalenian is closely related to that of southern France (Magdalenian V and VI), being characterized by the presence of harpoons. Again there are two facies (called A and B) that appear geographically intertwined, though the facies A (dates: 15,400–13,870 BP) is absent in the Basque Country and the facies B (dates 12,869–12,282 BP) is rare in Asturias.

In Portugal there have been some findings of the upper Magdalenian north of Lisbon (Casa da Moura, Lapa do Suão). A possible intermediate site is La Dehesa (Salamanca, Spain), that is clearly associated with that of the Cantabrian area.

In the Mediterranean area, Catalonia again is directly connected with the French sequence, at least in the late phases. Instead the rest of the region shows a unique local evolution known as Parpallense.

The sometimes called Parpalló "Magdalenian" (extended by all the south-east) is actually a continuity of the local Gravetto-Solutrean. Only the late upper Magdalenian actually includes true elements of this culture, like proto-harpoons. Radicarbon dates for this phase are of c. 11,470 BP (Borran Gran). Other sites give later dates that actually approach the Epi-Paleolithic.[10]

Paleolithic art

Together with France, the Iberian peninsula is one of the prime areas of Paleolithic cave paintings, with 18 caves forming the World Heritage Site of Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain; they are close to the coast in Cantabria, Asturias and the Basque Country. This artistic manifestation is found most importantly in the northern Cantabrian area, where the earliest manifestations, for example the Caves of Monte Castillo are as old as Aurignacian times.

The practice of this mural art increases in frequency in the Solutrean period, when the first animals are drawn, but it is not until the Magdalenian cultural phase when it becomes truly widespread, being found in almost every cave.

Most of the representations are of animals (bison, horse, deer, bull, reindeer, goat, bear, mammoth, moose) and are painted in ochre and black colors but there are exceptions and human-like forms as well as abstract drawings also appear in some sites.

In the Mediterranean and interior areas, the presence of mural art is not so abundant but exists as well since the Solutrean.

Also, several examples of open-air art exist. The monumental Côa Valley, in Vila Nova de Foz Côa Municipality, Portugal, has petroglyphs dating up to 22,000 years ago. These document continuous human occupation from the end of the Paleolithic Age. Hundreds of panels with thousands of animal figures were carved over several millennia, representing the most remarkable open-air ensemble of Paleolithic art on the Iberian Peninsula.[13][14]

Other examples include Chimachias, Los Casares or La Pasiega, or, in general, the caves principally in Cantabria (in Spain).

Epipaleolithic and Mesolithic

Around 10,000 BC, an interstadial deglaciation called the Allerød Oscillation occurred, weakening the rigorous conditions of the last ice age. This climatic change also represents the end of the Upper Palaeolithic period, beginning the Epipaleolithic. Depending on the terminology preferred by any particular source, the Mesolithic begins after the Epipaleolithic, or includes it. If the Epipaleolithic is not included in it, the Mesolithic is a relatively brief period in Iberia.

As the climate became warmer, the late Magdalenian peoples of Iberia modified their technology and culture. The main techno-cultural change is the process of microlithization: the reduction of size of stone and bone tools, also found in other parts of the World. Also the cave sanctuaries seem to be abandoned and art becomes rarer and mostly done on portable objects, such as pebbles or tools.

It also implies changes in diet, as the megafauna virtually disappears when the steppe becomes woodlands. In this period, hunted animals are of smaller size, typically deer or wild goats, and seafood becomes an important part of the diet where available.

Azilian and Asturian

The first Epipaleolithic culture is the Azilian, also known as microlaminar microlithism in the Mediterranean. This culture is the local evolution of Magdalenian, parallel to other regional derivatives found in Central and Northern Europe. Originally found in the old Magdalenian territory of Vasco-Cantabria and the wider Franco-Cantabrian region, Azilian-style culture eventually expanded to parts of Mediterranean Iberia as well. It reflected a much warmer climate, leading to thick woodlands, and the replacement of large herd animals with smaller and more elusive forest-dwellers.

An archetypical Azilian site in the Iberian peninsula is Zatoya (Navarre), where it is difficult to discern the early Azilian elements from those of late Magdalenian (this transition dated to 11,760 BP).[10] Full Azilian in the same site is dated to 8,150 BP, followed by appearance of geometric elements at a later date, that continue until the arrival of pottery (subneolithic stage).

In the Mediterranean area, virtually this same material culture is often named microlaminar microlithism because it lacks of the bone industry typical of Franco-Cantabrian Azilian. It is found in parts of Catalonia, Valencian Community, Murcia and Mediterranean Andalusia. It has been dated in Les Mallaetes at 10,370 BP.[10]

The Asturian culture was a successor to the Azilian, moved slightly to the west, whose distinctive tool was a pick-axe for picking limpets off rocks.

Geometrical microlithism

In the late phases of the Epipaleolithic a new trend arrives from the north: the geometrical microlithism, directly related to Sauveterrian and Tardenoisian cultures of the Rhin-Danube region.

While in the Franco-Cantabrian region it has a minor impact, not altering the Azilian culture substantially, in Mediterranean Iberia and Portugal its arrival is more noticeable. The Mediterranean geometrical microlithism has two facies:

- The Filador facies is directly related to French Sauveterrian and is found in Catalonia, north of the Ebro river.

- The Cocina facies is more widespread and, in many sites (Málaga, Spain), shows a strong dependence of fishing and seafood gathering. The Portuguese sites (south of the Tagus, Muge group) have given dates of c.7350 .[10]

Art

The rock art found at over 700 sites along the eastern side of Iberia is the most advanced and widespread surviving from this period, certainly in Europe, and arguably in the world. It is strikingly different from the Upper Palaeolithic art found along the northern coast, with narrative scenes with large numbers of small sketchily painted human figures, rather than the superbly observed individual animal figures that characterise the earlier period. When it appears in the same scene as animals, the human figure runs towards them. The most common scenes by far are of hunting, and there are scenes of battle and dancing, and possibly agricultural tasks and managing domesticated animals. In some scenes gathering honey is shown, most famously at Cuevas de la Araña en Bicorp (illustrated below). Humans are naked from the waist up, but women have skirts and men sometimes skirts or gaiters or trousers of some sort, and headdresses and masks are sometimes seen, which may indicate rank or status.

Neolithic

.JPG.webp)

In the 6th millennium BC, Andalusia experiences the arrival of the first agriculturalists. Their origin is uncertain (though North Africa is a serious candidate) but they arrive with already developed crops (cereals and legumes). The presence of domestic animals instead is unlikely, as only pig and rabbit remains have been found and these could belong to wild animals. They also consumed large amounts of olives but it's uncertain too whether this tree was cultivated or merely harvested in its wild form. Their typical artifact is the La Almagra style pottery, quite variegated.[10]

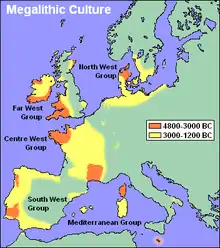

The Andalusian Neolithic also influenced other areas, notably Southern Portugal, where, soon after the arrival of agriculture, the first dolmen tombs begin to be built c. 4800 BC, being possibly the oldest of their kind anywhere.[10]

C. 4700 BC Cardium pottery Neolithic culture (also known as Mediterranean Neolithic) arrives to Eastern Iberia. While some remains of this culture have been found as far west as Portugal, its distribution is basically Mediterranean (Catalonia, Valencian region, Ebro valley, Balearic islands).

The interior and the northern coastal areas remain largely marginal in this process of spread of agriculture. In most cases it would only arrive in a very late phase or even already in the Chalcolithic age, together with Megalithism.

The location of Perdigões, in Reguengos de Monsaraz, is thought to have been an important location. Twenty small ivory statues dating to 4,500 years BP have been discovered there since 2011. It has constructions dating back to about 5,500 years. It has a necropolis. Outside the location there is a cromlech.[15] The Almendres Cromlech site, in Évora, has megaliths from the late 6th to the early 3rd millennium BC.[16] The Anta Grande do Zambujeiro, also in Évora, is dated between the early 4th and the mid 3rd millennium BC.[17][18] The Dolmen of Cunha Baixa, in Mangualde Municipality, is dated between 3000 and 2500 BC.[19] The Cave of Salemas was used as a burial ground during the Neolithic.[8]

Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic or Copper Age is the earliest phase of metallurgy. Copper, silver and gold started to be worked then, though these soft metals could hardly replace stone tools for most purposes. The Chalcolithic is also a period of increased social complexity and stratification and, in the case of Iberia, that of the rise of the first civilizations and of extensive exchange networks that would reach to the Baltic and Africa. The conventional date for the beginning of Chalcolithic in Iberia is c. 3000 BC. In the following centuries, especially in the south of the peninsula, metal goods, often decorative or ritual, become increasingly common. Additionally there is an increased evidence of exchanges with areas far away: amber from the Baltic and ivory and ostrich-egg products from Northern Africa.[10]

The Beaker culture was present in Iberia during the Chalcolithic.[20] Gordon Childe interpreted the presence of its characteristic artefact as the intrusion of "missionaries" expanding from Iberia along the Atlantic coast, spreading knowledge of Mediterranean copper metallurgy. Stephen Shennan interpreted their artefacts as belonging to a mobile cultural elite imposing itself over the indigenous substrate populations. Similarly, Sangmeister (1972) interpreted the "Beaker folk" (Glockenbecherleute) as small groups of highly mobile traders and artisans. Christian Strahm (1995) used the term "Bell Beaker phenomenon" (Glockenbecher-Phänomen) as a compromise in order to avoid the term "culture".

The Bell Beaker artefacts at least in their early phase are not distributed across a contiguous areal as is usual for archaeological cultures, but are found in insular concentrations scattered across Europe. Their presence is not associated with a characteristic type of architecture or of burial customs. However, the Bell Beaker culture does appear to coalesce into a coherent archaeological culture in its later phase.

More recent analyses of the "Beaker phenomenon", published since the 2000s, have persisted in describing the origin of the "Beaker phenomenon" as arising from a synthesis of elements, representing "an idea and style uniting different regions with different cultural traditions and background. "Archaeogenetics studies of the 2010s have been able to resolve the "migrationist vs. diffusionist" question to some extent. The study by Olalde et al. (2017) found only "limited genetic affinity" between individuals associated with the Beaker complex in Iberia and in Central Europe, suggesting that migration played a limited role in its early spread from Iberia. However, the same study found that the further dissemination of the mature Beaker complex was very strongly linked to migration. The spread and fluidity of the Beaker culture back and forth between the Rhine and its origin source in the peninsula may have introduced high levels of steppe-related ancestry, resulting in a near-complete transformation of the local gene pool within a few centuries, to the point of replacement of about 90% of the local Mesolithic-Neolithic patrilineal lineages.

The origin of the "Bell Beaker" artefact itself has been traced to the early 3rd millennium. The earliest examples of the "maritime" Bell Beaker design have been found at the Tagus estuary in Portugal, radiocarbon dated to c. the 28th century BC. The inspiration for the Maritime Bell Beaker is argued to have been the small and earlier Copoz beakers that have impressed decoration and which are found widely around the Tagus estuary in Portugal. Turek has recorded late Neolithic precursors in northern Africa, arguing the Maritime style emerged as a result of seaborne contacts between Iberia and Morocco in the first half of the third millennium BCE. In only a few centuries of their maritime spread, by 2600 BC. they had reached the rich lower Rhine estuary and further upstream into Bohemia and beyond the Elbe where they merged with Corded Ware culture, as also in the French coast of Provence and upstream the Rhone into the Alps and Danube.

A significant Chalcolithic archeological site in Portugal is the Castro of Vila Nova de São Pedro. Other settlements from this period include Pedra do Ouro and the Castro of Zambujal.[20] Megaliths were created during this period, having started earlier, during the late 5th, and lasting until the early 2nd millennium BC.[20] The Castelo Velho de Freixo de Numão, in Vila Nova de Foz Côa Municipality, was populated from about 3000 to 1300 BC.[21] The Cerro do Castelo de Santa Justa, in Alcoutim, is dated to the 3rd millennium BC,[22] between 2400 and 1900 BC.[20]

It is also the period of the great expansion of megalithism, with its associated collective burial practices. In the early Chalcolithic period this cultural phenomenon, maybe of religious undertones, expands along the Atlantic regions and also through the south of the peninsula (additionally it's also found in virtually all European Atlantic regions). In contrast, most of the interior and the Mediterranean regions remain refractary to this phenomenon.

Another phenomenon found in the early chalcolithic is the development of new types of funerary monuments: tholoi and artificial caves. These are only found in the more developed areas: southern Iberia, from the Tagus estuary to Almería, and SE France.

Eventually, c. 2600 BC, urban communities began to appear, again especially in the south. The most important ones are Los Millares in SE Spain and Zambujal (belonging to Vila Nova de São Pedro culture) in Portuguese Estremadura, that can well be called civilizations, even if they lack of the literary component.

It is very unclear if any cultural influence originated in the Eastern Mediterranean (Cyprus?) could have sparked these civilizations. On one side the tholos does have a precedent in that area (even if not used yet as tomb) but on the other there is no material evidence of any exchange between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, in contrast with the abundance of goods imported from Northern Europe and Africa.[10]

Since c. 2150 BC, the Bell Beaker culture intrudes in Chalcolithic Iberia. After the early Corded style beaker, of quite clear Central European origin, the peninsula begins producing its own types of Bell Beaker pottery. Most important is the Maritime or International style that, associated especially with Megalithism, is for some centuries abundant in all the peninsula and southern France.

Since c. 1900 BC, the Bell Beaker phenomenon in Iberia shows a regionalization, with different styles being produced in the various regions: Palmela type in Portugal, Continental type in the plateau and Almerian type in Los Millares, among others.[10]

Like in other parts of Europe, the Bell Beaker phenomenon (speculated to be of trading or maybe religious nature) does not significantly alter the cultures it inserts itself in. Instead the cultural contexts that existed previously continue basically unchanged by its presence.

Bronze Age

Early Bronze

The center of Bronze Age technology is in the southeast since c. 1800 BC.[10] There the civilization of Los Millares was followed by that of El Argar, initially with no other discontinuity than the displacement of the main urban center some kilometers to the north, the gradual appearance of true bronze and arsenical bronze tools and some greater geographical extension. The Argarian people lived in rather large fortified towns or cities.

From this center, bronze technology spread to other areas. Most notable are:

- Bronze of Levante: in the Valencian Community. Their towns were smaller and show intense interaction with their neighbours of El Argar.

- South-Western Iberian Bronze: in southern Portugal and SW Spain. These poorly defined archaeological horizons show the presence of bronze daggers and an expansive trend in northwards direction.

- Cogotas I culture (Cogotas II is Iron Age Celtic): the pastoralist peoples of the plateau become for the first time culturally unified. Their typical artifact is a rough troncoconic pottery.

Some areas like the civilization of Vila Nova seem to have remained apart from the spread of bronze metallurgy remaining technically in the Chalcolithic period for centuries.

Middle Bronze

This period is basically a continuation of the previous one. The most noticeable change happens in the El Argar civilization, which adopts the Aegean custom of burial in pithoi.[10] This phase is known as El Argar B, beginning c. 1500 BC.

The North-West (Galicia and northern Portugal), a region that held some of the largest reserves of tin (needed to make true bronze) in Western Eurasia, became a focus for mining, incorporating then the bronze technology. Their typical artifacts are bronze axes (Group of Montelavar).

The semi-desert region of La Mancha shows its first signs of colonization with the fortified scheme of the Motillas (hill forts). This group is clearly related to the Bronze of Levante, showing the same material culture.[10]

Late Bronze

C. 1300 BC several major changes happen in Iberia, among them:

- The Chalcolithic culture of Vila Nova vanishes, possibly in direct relation to the silting of the canal connecting the main city Zambujal with the sea.[23] It is replaced by a non-urban culture, whose main artifact is an externally burnished pottery.

- El Argar also disappears as such, what had been a very homogeneous culture, a centralized state for some, becomes an array of many post-Argaric fortified cities.

- The Motillas are abandoned.

- The proto-Celtic Urnfield culture appears in the North-East, conquering all Catalonia and some neighbouring areas.

- The Lower Guadalquivir valley shows its first clearly differentiated culture, defined by internally burnished pottery. This group might have some relation with the semi-historical, yet-to-be-found Tartessos.

- Western Iberian Bronze cultures show some degree of interaction, not just among them but also with other Atlantic cultures in Britain, France and elsewhere. This has been called the Atlantic Bronze complex.[10]

Iron Age

The Iron Age in the Iberian peninsula has two focuses: the Hallstatt-related Iron Age Urnfields of the North-East and the Phoenician colonies of the South.

During the Iron Age, considered the protohistory of the territory, the Celts came, in several waves, starting possibly before 600 BC.[20]

The Southwest Paleohispanic script, also called Tartessian, present in the Algarve and Lower Alentejo from about the late 8th to the 5th century BC, is possible the oldest script in Western Europe and it could have come from the Eastern Mediterranean, perhaps from Anatolia or Greece.[20]

Early Iron Age cultures

Since the late 8th century BC, the Urnfield culture of North-East Iberia began to develop Iron metallurgy and, eventually, elements of the Hallstatt culture. The earliest elements of this culture were found along the lower Ebro river, then gradually expanded upstream to La Rioja and in a hybrid local form to Alava. There was also expansion southwards into Castelló, with less marked influences reaching further south. Additionally, some offshoots have been detected along the Iberian Mountains, possibly a prelude to the formation of the Celtiberi.[10]

During this period, the social differentiation became more visible with evidence of local chiefdoms and a horse-riding elite. It is possible that these transformations represent the arrival of a new wave of cultures from central Europe.

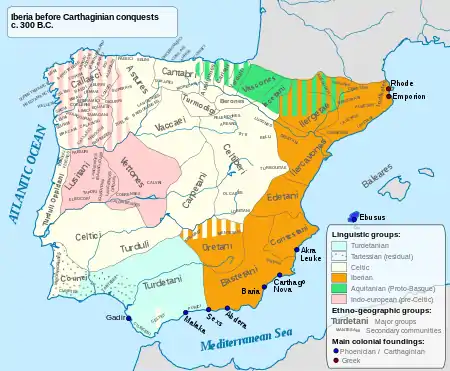

From these outposts in the Upper Ebro and the Iberian mountains, Celtic culture expanded into the plateau and the Atlantic coast. Several groups can be described:[10]

- The Bernorio-Miraveche group (northern Burgos and Palencia provinces), that would influence the peoples of the northern fringe.

- The north-west Castro culture, in today's Galicia and northern Portugal, a Celtic culture with peculiarities, due to the persistence of aspects of an earlier Atlantic Bronze Age culture.

- The Duero group, possibly the precursor of the Celtic Vaccei.

- The Cogotas II culture, likely precursor of the Celtic or Celtiberian Vettones (or a pre-Celtic culture with substantial Celtic influences), a markedly cattle-herder culture that gradually expanded southwards into what is today's Extremadura.

- The Lusitanian culture, the precursor of the Lusitani tribe, located in what is today's central Portugal and Extremadura in western Spain, is generally not considered Celtic since the Lusitanian language does not meet some the accepted definitions of a Celtic language.[24] Its relationship with the surrounding Celtic culture is unclear. Some believe it was essentially a pre-Celtic Iberian culture with substantial Celtic influences, while others argue that it was an essentially Celtic culture with strong indigenous pre-Celtic influences. There have been arguments for classifying its language as either Italic, a form of archaic Celtic, or proto-Celtic.

All these Indo-European groups have some common elements, like combed pottery since the 6th century and uniform weaponry.

After c. 600 BC, the Urnfields of the North-East were replaced by the Iberian culture, in a process that wasn't completed until the 4th century BC.[10] This physical separation from their continental relatives would mean that the Celts of the Iberian peninsula never received the cultural influences of La Tène culture, including Druidism.

Phoenician colonies and influence

The Phoenicians of Asia, Greeks of Europe, and Carthaginians of Africa all colonized parts of Iberia to facilitate trade. During the 10th century BC, the first contacts between Phoenicians and Iberia (along the Mediterranean coast) were made. This century also saw the emergence of towns and cities in the southern littoral areas of eastern Iberia.

The Phoenicians founded colony of Gadir (modern Cádiz) near Tartessos. The foundation of Cádiz, the oldest continuously-inhabited city in western Europe, is traditionally dated to 1104 BC, although, as of 2004, no archaeological discoveries date back further than the 9th century BC. The Phoenicians continued to use Cádiz as a trading post for several centuries leaving a variety of artifacts, most notably a pair of sarcophaguses from around the 4th or 3rd century BC. Contrary to myth, there is no record of Phoenician colonies west of the Algarve (namely Tavira), even though there might have been some voyages of discovery. Phoenician influence in what is now Portuguese territory was essentially through cultural and commercial exchange with Tartessos.

During the 9th century BC, the Phoenicians, from the city-state of Tyre founded the colony of Malaka (modern Málaga)[25] and Carthage (in North Africa). During this century, Phoenicians also had great influence on Iberia with the introduction the use of Iron, of the Potter's wheel, the production of olive oil and wine. They were also responsible for the first forms of Iberian writing, had great religious influence and accelerated urban development. However, there is no real evidence to support the myth of a Phoenician foundation of the city of Lisbon as far back as 1300 BC, under the name Alis Ubbo ("Safe Harbour"), even if in this period there are organized settlements in Olissipona (modern Lisbon, in Portuguese Estremadura) with Mediterranean influences.

There was strong Phoenician influence and settlement in the city of Balsa (modern Tavira in the Algarve), in the 8th century BC. Phoenician influenced Tavira was destroyed by violence in the 6th century BC. With the decadence of Phoenician colonization of the Mediterranean coast of Iberia in the 6th century BC many of the colonies are deserted. The 6th century BC also saw the rise of the colonial might of Carthage, which slowly replaced the Phoenicians in their former areas of dominion.

Greek colonies

The Greek colony at what now is Marseilles began trading with the Iberians on the eastern coast around the 8th century BC. The Greeks finally founded their own colony at Ampurias, in the eastern Mediterranean shore (modern Catalonia), during the 6th century BC beginning their settlement in the Iberian peninsula. There are no Greek colonies west of the Strait of Gibraltar, only voyages of discovery. There is no evidence to support the myth of an ancient Greek founding of Olissipo (modern Lisbon) by Odysseus.

The Tartessian culture

The name Tartessian, when applied in archaeology and linguistics does not necessarily correlate with the semi-mythical city of Tartessos but only roughly with the area where it is typically assumed it should have been located.

The Tartessian culture of southern Iberia actually is the local culture as modified by the increasing influence of eastern Mediterranean elements, especially Phoenician. Its core area is Western Andalusia, but soon extends to Eastern Andalusia, Extremadura and the Lands of Murcia and Valencia, where a Tartessian complex, rooted in the local Bronze cultures, is in the last stages of the Bronze Age (ninth-eighth centuries BC) before Phoenician influences can be seen clearly.

The full Tartessian culture, beginning c.720 BC, also extends to southern Portugal, where is eventually replaced by Lusitanian culture. One of the most significant elements of this culture is the introduction of the potter's wheel, that, along with other related technical developments, causes a major improvement in the quality of the pottery produced. There are other major advances in craftsmanship, affecting jewelry, weaving and architecture.[10] This latter aspects is especially important, as the traditional circular huts were then gradually replaced by well finished rectangular buildings. It also allowed for the construction of the tower-like burial monuments that are so typical of this culture.

Agriculture also seems to have experienced major advances with the introduction of steel tools and, presumably, of the yoke and animal traction for the plough. In this period it's noticeable the increase of cattle accompanied by some decrease of sheep and goat types.[10]

Another noticeable element is the major increase in economical specialization and social stratification. This is very noticeable in burials, with some showing off great wealth (chariots, gold, ivory), while the vast majority are much more modest. There is much diversity in burial rituals in this period but the elites seem to converge in one single style: a chambered mound. Some of the most affluent burials are generally attributed to local monarchs.

One of the developments of this period is writing, a skill which was probably acquired through contact with the Phoenicians. John T. Koch controversially claimed to have deciphered the extant Tartessian inscriptions and to have tentatively identified the language as an earlier form of the Celtic languages now spoken in the British Isles and Brittany in the book 'Celtic from the West', published in 2010.[26][27] However, the linguistic mainstream continues to treat Tartessian as an unclassified, possibly pre-Indo-European language, and Koch's decipherment of the Tartessian script and his theory for the evolution of Celtic has been strongly criticized.[28]

The Iberian culture

In the Iberian culture people were organized in chiefdoms and states. Three phases can be identified: the Ancient, the Middle and the Late Iberian period.

With the arrival of Greek influences, not limited to their few colonies, the Tartessian culture begins to transform itself, especially in the South East. This late period is known as the Iberian culture, that in Western Andalusia and the non-Celtic areas of Extremadura is called Ibero-Turdetanian because of its stronger links with the Tartessian substrate.

The Hellenic influence is visible in the gradual change of the style of their monuments that approach more and more the models arrived from the Greek world.[10] Thus the obelisk-like funerary monuments of the previous period now adopt a column like form, totally in line with Greek architecture.

By the middle of the 5th century, aristocratic power was increased and resulted in the abandonment and transformation of the orientalizing model. The oppidum appeared and became the socio-economic model of the aristocratic class. The commerce was also one of the principal sources of aristocratic control and power. In the south east, between the end of the 5th and the end of the 4th century BC, appeared a highly hierarchical aristocratic society. There were different forms of political control. The power and control seemed to be in the hand of kings or reguli.

Iberian funerary customs are dominated by cremation necropolis, that are partly due to the persistent influences of the Urnfield culture, but they also include burial customs imported from the Greek cultural area (mudbrick rectangular mound).[10]

Urbanism was important in the Iberian cultural area, especially in the south, where Roman accounts mention hundreds of oppida (fortified towns). In these towns (some quite large, some mere fortified villages) the houses were typically arranged in contiguous blocks, in what seems to be another Urnfield cultural influx.

The Iberian script evolved from the Tartessian one with Greek influences that are noticeable in the transformation of some characters. In a few cases a variant of Greek alphabet (Ibero-Ionian script) was used to write Iberian as well.

The transformation from Tartessian to Iberian culture was not sudden but gradual and was more marked in the East, where it begins in the 6th century BC, than in the south-west, where it is only noticeable since the 5th century BC and much more tenuous. A special case is the north-east where the Urnfield culture was Iberized but keeping some elements from the Indo-European substrate.[10]

Post-Tartessos Iron Age

Also during the 6th century BC there was a cultural shift in south-western Iberia (what is now southern Portugal and the nearby areas of Andalusia) after the fall of Tartessos, with a strong Mediterranean character that prolonged and modified Tartessian culture. This occurred mainly in Low Alentejo and the Algarve, but had littoral extensions up to the Sado mouth (namely the important city of Bevipo, modern Alcácer do Sal). The first form of writing in western Iberia (south of Portugal), the Southwest Paleohispanic script (still to be translated), dated to the 6th century BC, denotes strong Tartessian influence in its use of a modified Phoenician alphabet. In these writings the word "Conii" (similar to Cunetes or Cynetes, the people of the Algarve) appears frequently.

In the 4th century BC, the Celtici appear, a late expansion of Celtic culture into the south west (southern Extremadura, the Alentejo and northern Algarve areas). The Turduli and Turdetani, probably descendants of the Tartessians, although celticized, became established in the area of the Guadiana river, in the south of modern Portugal. A series of cities in the Algarve, such as Balsa (Tavira), Baesuris (Castro Marim), Ossonoba (Faro) and Cilpes (Silves), became inhabited by the Cynetes.

Arrival of Romans and Punic Wars

During the 4th century BC, Rome began to rise as a Mediterranean power rival to the north African based Carthage. After suffering defeat to the Romans in the First Punic War (264–241 BC), the Carthaginians began to extend their power into the interior of Iberia from their south eastern coastal settlements but this empire was to be short lived. In the Second Punic War (218–202 BC), the Carthaginian general Hannibal marched his armies, which included Iberians, from Iberia, across the Pyrenees and the Alps and attacked the Romans in Italy. Despite many victories, he was finally defeated and the Romans took revenge by destroying Carthage. Starting in the north-east, Rome began its conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

Archaeogenetics

In recent years, the DNA of individuals from Neolithic and Chalcolithic Iberia has been analyzed. With regards to Y-DNA, most Iberians from this period have been found to be carriers of I2a and subclades of it. R1b, G, and H also occurs. With regards to mtDNA, H, V, X, J, K, T and N has been found.[29][30][31]

Footnotes

- Sáez Juárez, Juana (December 2002). "Los primeros pobladores de la Península Ibérica. Cronología y posibles rutas". Página de Historia (in Spanish). Universidad de Valencia. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "Itinerários Arqueológicos do Alentejo e Algarve". igespar.pt (in Portuguese). Government of Portugal. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Gruta do Escoural". cm-montemornovo.pt (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Roach, John (13 September 2006). "Neandertals' Last Stand Was in Gibraltar, Study Suggests". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- Tattersall I, Schwartz JH (June 1999). "Hominids and hybrids: The place of Neanderthals in human evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (13): 7117–9. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7117T. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7117. PMC 33580. PMID 10377375.

Thus, although many students of human evolution have lately begun to look favorably on the view that these distinctive hominids merit species recognition in their own right as Homo neanderthalensis (e.g., refs. 4 and 5), at least as many still regard them as no more than a strange variant of our own species, Homo sapiens

- Garrod, Dorothy A. E.; Buxton, L. H.; Smith, E. Elliot; Bate, Dorothea M. A. (1928). "Excavation of a Mousterian Rock-shelter at Devil's Tower, Gibraltar". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 58: 33–113. JSTOR 4619528.

- Ian Tattersall, Jeffrey H. Schwartz (22 June 1999). "Hominids and hybrids: The place of Neanderthals in human evolution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Gruta de Salemas". Portal do Arqueólogo (in Portuguese). IGESPAR. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- João Zilhão (22 December 1998). "The Extinction of Iberian Neandertals and Its Implications for the Origins of Modern Humans in Europe" (PDF). Studentski klub arheologa. Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- F. Jordá Cerdá et al., Historia de España I: Prehistoria, 1986. ISBN 84-249-1015-X

- Duarte; Maurício, J; Pettitt, PB; Souto, P; Trinkaus, E; Van Der Plicht, H; Zilhão, J; et al. (1999). "The early Upper Paleolithic human skeleton from the Abrigo do Lagar Velho (Portugal) and modern human emergence in the Iberian Peninsula". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. PNAS. 96 (13): 7604–7609. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.7604D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7604. PMC 22133. PMID 10377462.

- Aedeen Cremin (15 October 2007). Archaeologica. Frances Lincoln Limited. ISBN 9780711228221. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- "Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde". igespar.pt. Government of Portugal. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Prehistoric Rock Art Sites in the Côa Valley and Siega Verde". Unesco.org. UNESCO World Heritage List.

- Lucinda Canelas and Marta Portocarrero (8 August 2012). "Estatuetas descobertas no Alentejo têm 4500 anos e cabem na palma da mão". Público (in Portuguese). Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- "Cromeleque e menir, na Herdade dos Almendres". igespar.pt (in Portuguese). Government of Portugal. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Anta Grande do Zambujeiro de Valverde". igespar.pt (in Portuguese). Government of Portugal. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Manuel Branco (1993). "Anta Grande do Zambujeiro / Anta Grande do Zambujeiro de Valverde". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico (SIPA) (in Portuguese). Instituto da Habitação e da Reabilitação Urbana. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Lina Marques (1995). "Anta da Cunha Baixa / Casa da Orca". Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico (SIPA) (in Portuguese). Instituto da Habitação e da Reabilitação Urbana. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Garcia, José Manuel (1989). História de Portugal: Uma Visão Global. Lisboa: Editorial Presença. pp. 28–32. ISBN 978-9722309899.

- "Castelo Velho de Freixo de Numão". igespar.pt (in Portuguese). Government of Portugal. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- "Cerro do Castelo de Santa Justa". igespar.pt (in Portuguese). Government of Portugal. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- Deutsches Archälogisches Institut: Zambujal, Torres Vedras Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine (in English)

- Koch, John T (2011). Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3

- Aubet, María Eugenia (2001-09-06). The Phoenicians and the West: politics, colonies and trade. ISBN 9780521795432. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- Koch, John T (2010). Celtic from the West Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 187–295. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4.

- Koch, John T (2011). Tartessian 2: The Inscription of Mesas do Castelinho ro and the Verbal Complex. Preliminaries to Historical Phonology. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK. pp. 1–198. ISBN 978-1-907029-07-3. Archived from the original on 2011-07-23.

- Broderick, George (2010). "Die vorrömischen Sprachen auf der iberischen Halbinsel". In Hinrichs, Uwe (ed.). Das Handbuch der Eurolinguistik (in German) (1st ed.). Wiesbaden, Germany: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 304–305. ISBN 978-3-447-05928-2.

- Lipson 2017.

- Mathieson 2018.

- Narasimhan 2019.

See also

References

- Alberro, Manuel and Arnold, Bettina (eds.), e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, Volume 6: The Celts in the Iberian Peninsula, University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee, Center for Celtic Studies, 2005.

- Cerdá, F. Jordá et al., History of Spain 1: Prehistory, Gredos, 1986. ISBN 84-249-1015-X

- Mattoso, José (dir.), História de Portugal. Primeiro Volume: Antes de Portugal, Lisboa, Círculo de Leitores, 1992. (in Portuguese)

- Lipson, Mark (November 16, 2017). "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers". Nature. Nature Research. 551 (7680): 368–372. doi:10.1038/nature24476. PMC 5973800. PMID 29144465.

- Mathieson, Iain (February 21, 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M. (September 6, 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. bioRxiv 10.1101/292581. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- The concept of Atlantic Bronze Age in the framework of 20th century archeological thinking - in Portuguese, English and French

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Prehistoric Iberia. |

.png.webp)