Serbs in North Macedonia

Serbs (Macedonian: Србите во Северна Македонија, Serbian: Срби у Северној Македонији / Srbi u Severnoj Makedoniji) are one of the constitutional peoples of North Macedonia. Numbering about 36,000 inhabitants (2002 census), they are based on the medieval populations, as well as on the 20th century Yugoslav policy of serbianization, and on later relocation or migration of ethnic Serbs.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 35,939 (2002)[1] | |

| Religion | |

| Serbian Orthodox Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Macedonians, Bosniaks in North Macedonia |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Serbs |

|---|

|

Historical overview

Serbia became for the first time independent under Časlav ca. 930, only to fall ca. 960 under Byzantine, later under Bulgarian and then again under Byzantine rule.[2] From the end of the 11th to the end of the 13th century, the Serbian rulers made several attempts to penetrate into the region and briefly conquered its northernmost territories. In fact the whole of today North Macedonia was taken for the first time by medieval Serbia, during the 1280-s.[3] The territory of today's North Macedonia was part of the Serbian Kingdom and Empire to the Battle of Kosovo (1389) when it was conquered by the Ottomans. The South Slavic Orthodox people now lived under a foreign, Muslim power, in whose eyes all Orthodox people were regarded part of the Rum Millet. In tax registries, the Orthodox Christians were recorded as "infidels" (see giaour).[4] Atrocities, failed rebellions and tax increases prompted several mass migrations to the north. Minor revolts took place in Ottoman Macedonia, although the liberation of these lands came to fruit in the late 19th and early 20th century, with Serbian and Bulgarian effort. In the decades before the Balkan Wars, the governments of Bulgaria and Serbia competed to win over the affiliation of the Slavic Orthodox population, which had traditionally identified as Bulgarian. During this time a separate Macedonian identity emerged in the local Slavs, who were divided by the affiliation of either the Bulgarian or Serbian Orthodox Church. By 1913, Serbia had captured most of present-day Macedonia, which subsequently was unified in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Socialist Yugoslavia with other South Slavic peoples. In 1991, with the outbreak of the Yugoslav Wars, the Socialist Republic of Macedonia became independent.

Medieval heritage

Early Middle Ages

The Early Slavs had pillaged the Balkans as early as the 520s. The South Slavic territories were called Sclaviniae (lit. Slav lands), and were from times independent from the Byzantine Empire.[5] In 577, some 100,000 Slavs poured into Thrace and Illyricum, pillaging cities and settling down.[6] By the 580s, as the Slav communities on the Danube became larger and more organised, and as the Avars exerted their influence, raids became larger and resulted in permanent settlement. By 581, many Slavic tribes had settled the land around Thessaloniki, though never taking the city itself, creating a Macedonian Sclavinia. In 586 AD, as many as 100,000 Slav warriors raided Thessaloniki.[7] In De Administrando Imperio, the Serbs trace their origin to the migration of the White Serbs led by the Unknown Archont, who took the protection of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (610-641).[8] Part of the White Serbs, who settled in modern Greek Macedonia[9] (around Servia), subsequently moved to the north and settled the lands that would become the early Serbian Principality. Constans II conquered Sclavinia in 656-657, "capturing many and subduing them",[10] he also resettled Slavs from the Vardar area to Asia Minor, to a city named Gordoservon (Greek: Γορδοσερβα, City of Serbs).[11][12] The "Sclaviniae of Macedonia" (Sclavenias penes Macedoniam) were conquered in 785 by Constantine VI (r. 776–797), meanwhile, a Serbian Principality was established to the northwest.

In 681, Bulgars established the Bulgarian Khanate. By Peter I of Bulgaria's reign, a symbiosis between the Bulgars and Slavs occurred.[13] They established a form of Bulgarian national identity that, despite far from modern nationalism helped them to survive as a distinct ethnicity through the centuries.[14] Almost the whole of Macedonia was incorporated into Bulgaria in the mid-9th century during the rule of Khan Presian and his first minister Isbul[15] In 924 the Bulgarian Tsar Simeon I conquered Serbia for a short time. In 971-972, Eastern Bulgaria was conquered by John Tzimiskes, who burned down Bulgarian capital Preslav, capturing Tsar Boris II. The series of events are not clear due to contradicting sources, but it is sure that after 971, the Cometopuli brothers were the de facto rulers of the Western Bulgarian lands. Tsar Samuel then became a general under Roman I of Bulgaria, and co-ruled with him from 977 to 997. In 997, Roman died in captivity in Constantinople and Samuel was chosen as the new Emperor of Bulgaria. The political center of the Bulgarian realm was moved then to Macedonia, Ohrid served as capital and seat of the Bulgarian Patriarchate. By 997, Serbia had been conquered and made again subject to Bulgaria by Tsar Samuel. When the Byzantines finally defeated the Bulgarians in 1018, they regained control over most of the Balkans for the first time in four centuries.

High Middle Ages

1.Stefan Milutin's state; 2. Stefan Dragutin's state; 3. Milutin's acquisitions up to 1299; 4. Temporary loss of land in Hum.

In 1092, Grand Prince Vukan defeated an army sent by Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Alexios I responded by sending a much larger army, but it was stopped by Serbian envoys wanting to negotiate. Peace was concluded, and Alexios returned to tackle the plundering Cumans. Vukan however, immediately violated the treaty, launching an operation in the Vardar region, conquering the cities of Vranje, Skopje and Tetovo, with much loot. Vukan then sent messengers to Skopje, attempting to justify his actions as a consequence of unjust administration by the Byzantines. Alexios once again accepted peace, this time with the promise of Serbian hostages (a sign of definite peace), he returned to Constantinople and tasked the local leaders to repair the damaged structures on the border. Vukan did not send the hostages as promised, prompting Alexios to send John Komnenos, his nephew and commander of Dyrrhachium, towards Serbia. Vukan bought time by once again promising peace and hostages, only to simultaneously prepare an attack against them. In the night the Byzantine camp was surprise-attacked, with the majority of Byzantine soldiers being killed. Vukan went on to loot Skopje, Gornji- and Donji Polog, then ravaging Vranje and finally returning to Serbia. Alexios sent a last army, entering Lipljan without resistance, Vukan's messengers offered a conclusive peace and the previously promised hostages, and as Alexios had more problems in other places of the Empire, peace was agreed in 1094, and Vukan surrendered twenty hostages.[16]

The Byzantine Emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitos wrote in about 950 that the city of "Ta Serbia" situated north-west from Thessaloniki, derived its name from its Serbian founders in the early 7th century.[8] In the 12th century the city is mentioned as "Srpchishte" in the manuscript by the Byzantine author John Zonara.[17]

In 1189 the regions of Skopje and Tetovo were conquered by Stefan Nemanja.[18][19] In the late 1200s, Strez, a Bulgarian royalty of the Asen dynasty, fled to Serbia after a feud with Emperor Boril, who had taken the throne. Strez was for a time a Duke under Stefan Nemanjić and had by 1209 conquered most of Macedonia; from the Struma valley in the east, which bordered lands controlled by Boril, to Bitola and perhaps Ohrid in the west, and from Skopje in the north to Veria in the south. While Strez quickly gained the support of the local population and possibly inherited the remaining administration from Boril's rule, Serbian units nevertheless remained in his domains, either to guarantee his loyalty or with the intent to oust him and annex his lands.[20] In 1215 the region is taken by the Latins and Despotate of Epirus. In 1223, Theodore Komnenos ruled Macedonia as Despot of Epirus (proclaimed Emperor) with his Greek, Serb and Albanian lieutenants, who held lands to the Serbian border beyond Principality of Arbanon, Debar and Skoplje.[21]

In 1230, Theodore was defeated and captured by Emperor Ivan Asen II in the battle of Klokotnitsa, and lands west of Adrianople were once again part of Bulgaria; all the way to Durrës, Ivan Asen wrote in a memorial column that he conquered "His [Theodore Komnenos'] whole land from Odrin (Edirne) to Drach (Durrës), also Greek, Albanian and Serb" after the victory. Between 1246 and 1265, John Vatatzes conquered Macedonia from the Adrianople to the Vardar, while the Bulgarian emperor Michael I Asen had the towns west of the Vardar: Veles, Prilep and Ohrid. In 1252 John overcame Michael, and most of Macedonia towards the border of Serbia became a Nicaean province. After the 13th century, the Bulgarian empire lost Macedonia.[21]

Demetrios Chomatenos (Archbishop of Ohrid from 1216 to 1236) registered the naming culture of the South Slavs in Byzantine lands. In the 11th and 12th century, family names became more common and stable in Byzantium, adapted by the majority of people in Byzantine Macedonia, Epirus and other regions (including women, sometimes even monks), not only aristocrats. The South Slavs, however, maintained the tradition of only giving a personal name, sometimes with a Patronymic. There are only two cases of family names used by South Slavs during this time; Bogdanopoulos and Serbopoulos, both Slavic names with the Greek suffix -opoulos (όπουλος, originating in Peloponnese in the 10th century)[22]

In 1258, King Stefan Uroš I of Serbia took Skopje, Prilep and Kičevo from the Byzantines, but lost them shortly after in 1261. Serbia's conquest of the areas south of the Shara mountain chain, on the plains of Polog, and in Byzantine dominated places like Skopje and later Serres (Slavic: Ser) began with the expansion of Serbian King Milutin in 1282. With the victory over the Bulgarian army near Velbazhd (today's Kyustendil, Republic of Bulgaria) in 1331, the Morava and upper Vardar basins were secured for the Serbian state.

In a chrysobull dated 1294 of Andronicus II, the kataphrylax of Serres, "Jovan the Serb" was mentioned (Ἱωάννης ό Σἐρβος).[23] A Byzantine Serb military family of Thessaloniki, Deblitzenos, produced several soldiers holding titles such as pronoia, tzaousios, of which is also mentioned in documents of the Emperor.[24]

Late Middle Ages

.jpg.webp)

Right: Skopje Fortress, where Dušan adopted the title of Emperor at his coronation

In 1330, the Bulgarians attacked Serbia to stop the Serb penetration in Macedonia but were defeated in the battle of Velbazhd and while Bulgaria did not lose territory to Serbia, it could not prevent the latter from conquering Macedonia from the Byzantine Empire which had descended into a disastrous civil war. Of the event, both Dušan and his father recall that the Bulgarian emperor went against "Our country, against the lands of our fathers" and "Serbian territory" in relation to Macedonia.[25]

By 1345, the whole of Macedonia and parts of western Thrace were under Stefan Dušan's newly established Serbian Empire. After these successes Dušan proclaimed himself Emperor in 1345 at Serres and was crowned in Skopje on April 16, 1346 as "Emperor and autocrat of Serbs and Romans" (Greek Bασιλεὺς καὶ αὐτoκράτωρ Σερβίας καὶ Pωμανίας) by the Serbian Patriarch Joanikije II with the help of the Bulgarian Patriarch Simeon and the Archbishop of Ohrid, Nicholas.[26] Settling of Serb military and upper class citizens in Veria is mentioned in 1350, after Dušan the Mighty had conquered the town in between 1343 and 1347 and driven out all the inhabitants in fear of a revolt. Kantakouzenes asserts the Veria Serbs numbered 30 nobles and 1,500 soldiers, with their families.[24]

Ottoman rule

14th–17th century

The Ottoman invasion of Serbia was challenged at the Battle of Maritsa in 1371 by Serbian magnates Vukašin and Uglješa at the river Maritsa (in Bulgaria) which ended in Serbian defeat. This defeat, which culminated with the fall of Skoplje (Skopje) in 1392, Trnovo in 1393, in combination with the consequences of Serbian defeat at the Battle of Kosovo (1389) led to increasing presence of Ottoman Turks and Islam. The Ottomans converted population groups of Christian Slavs into Islam. In the middle of the 17th century, Grand Vizier Mehmed Köprülü successfully converted peoples of the Danube region, and notably the Serbs of Dibra (Debar) in western Macedonia.[27] The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć had spiritual power extending over Macedonia which continued the Serbian consciousness in a part of the South Slavic people of the region.[28] In the second half of the 15th century, Orthodox scribe Vladislav the Grammarian considered Macedonia a "Serb land".

In 1557, Mehmed Sokolović, an Ottoman commander of Serb origin, restored the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć, appointing his still Christian relative, Makarije, as the Patriarch. Tetovo, Skopje, Štip and Radovište are placed under the Serbian Church, while Ohrid, Monastir, Debar and Prilep remains under the Archbishopric of Ohrid (Greek).[29] In 1580, Jovan the Serb of Kratovo authored a Gospel book.[30] All missions to Russia from Macedonia were described as "Serbian", the first of which was in 1585, by Visarion, the Metropolitan of Kratovo and his entourage of monks from other places.[29] In 1641, the Metropolitan of Skopje, Simeon, travels to Russia and signs himself as "of the land of Serbia".[29] In 1687 a petition of Jeftimije, Metropolitan of Skoplje; "of the Serbian lands of the Church of Skoplje".[29] Although, unquestionably, the preceding were all under the Serb see, similarly clergy from the southern, Ecumenical dioceses, too described themselves as Serbs.[29] In 1625, Sergius of Greben mentions that he had been "consecrated by Nektarije, Archbishop of Ochrida, in the land of Serbia".[29] In 1634, Archbishop Avram of Ohrid replies that they came from "the Serbian country, from the town of Ochrida", similarly, in 1643, German of Kremenec says he is from the Serbian country, from Kostur, In 1648, "the Serb Dimitrje Nikolajev" from Kostur.[29] In 1704, "Serb Bratan Jovanov came to Russia from the land of Macedonia".[29]

18th century

From the beginning of the 18th century only Bulgarians were mentioned in Macedonia from foreign travallers, which means that they gradually absorbed the smaller Serbian ethnic element. According to Jovan Cvijic this mixture of Bulgarians and Serbs formed an amorphous Slavic mass, without clear ethnic consciousness. Per Cvijic these Slavs was to remain amorphous during the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century; but after the turn of the century these people, already Bulgarian in name, began to adopt a Bulgarian national identity.[31] In 1766 - 1767, the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid and the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć were abolished, the former dioceses becoming part of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which had Greek liturgy. In 1870 the Bulgarian Exarchate, which used Slavic liturgy and was deemed schismatic, was recognized by the Ottoman Empire, and subsequently two thirds of the Slavic population of Macedonia joined the Exarchate.

19th century

In the 19th century, the ethnic Serbian areas outside (south) of the Principality of Serbia were designated by Serbian cartographers as "Old Serbia", claiming that the inhabitants of this region (Kratovo, Skopje, Ovče Pole) described their native districts as "Serbian lands".[32]

The wars of Serbia and Montenegro, and then Russia, against the Ottomans motivated liberation movements among the people in Kosovo and Metohija and Macedonia (known at the time as "Old Serbia" or "southern Serbia").[33] Serbia sought to liberate the Kosovo Vilayet (sanjaks of Niš, Prizren, Skopje and Novi Pazar).[34] The Serbian Army was joined by southern Serbs who made up special volunteer detachments, a large number being from Macedonia, who wanted to liberate their home regions and unify them with Serbia.[33][35] These volunteers were infiltrated into the Kumanovo and Kriva Palanka districts.[36] When peace was signed between the Serbs and Ottomans, these groups conducted independent guerrilla fighting under the Serbian flag, which they carried and flew far south of the demarcation line.[33] The Serbian advance in Old Serbia (1877–78) was followed with uprisings for the Serbian cause in the region, including a notable one that broke out in the counties of Kumanovo, Kriva Palanka, and Kratovo,[35] known as the Kumanovo Uprising (January—May 1878). Following the uprising, the Ottoman government most notably prohibited the use of the appellation "Serbian". Also, Serbian nationalism in Macedonia was persecuted, while Bulgarian influence in the region became more common.[37] Mass migrations from Macedonia into Serbia followed after reprisals, with their former villages being settled by Albanians (such as in Matejche, Otlja, Kosmatec, Murgash and others).[38]

Popović, born in Ohrid, was one of the most prominent leaders of the First Serbian Uprising.

After the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78) and the suppressed Kumanovo Uprising, the Ottomans retaliated against the Serb population in the Ottoman Empire.[39] Because of the terror against the unprotected rayah (lower class, Christians), many left for the mountains, fled across the border into Serbia, from where they raided their home regions in order to revenge the atrocities carried out by the Ottomans.[39] After the war, the Serbian military government sent armament and aid to rebels in Kosovo and Macedonia.[40] Christian rebel bands were formed all over the region.[40] Many of those bands, privately organized and aided by the government, were established in Serbia and crossed into Ottoman territory.[40]

On 15 June 1878, an assembly was held at Zelenikovo, southeast from Skopje, where 5,000 villagers from the nahiye of Veles, Skopje, and Tikveš, requested unification with Serbia from Prince Milan IV.[41] The request came with 800 municipality, church, and monastery seals, as well as 5,000 signatures, fingerprints, and crosses.[41] Unfortunately, the carrier delivering the message was intercepted on 16 June on the Skopje-Kumanovo road,[42] by an Ottoman gendarmerie that had been tipped off by a Bulgarian teacher.[41] There was a shootout, and when the carrier's bullets had run out, he ripped and swallowed some of the papers before being shot.[41] Most of the petition was destroyed; however, 600 signatures were identified, and 200 of the identified signatories were immediately killed, while the rest were imprisoned and died in prison. 50 such prisoners later being released from Ottoman casemates.[41]

As Serbs of true and pure stock, of the purest and most intrinsically Serbian country... We for the last time implore on our knees... That we may in some manner and by some means be freed from the slavery of five centuries, and united with our country, the Principality of Serbia, and that the tears of blood of the Serbian martyrs may be stanched so that they, too, may become useful members of the European community of nations and of the Christian world; we do not desire to exchange the harsh Turkish slavery for the vastly harsher and darker Bulgarian slavery, which will be worse and more intolerable than that of the Turks which we are at present enduring, and will compel us in the end either to slay all our own people, or to abandon our country, to abandon our holy places, and graves, and all that we hold dear...

In the beginning of 1880, some 65 rebel leaders (glavari), from almost all provinces in southern Old Serbia and Macedonia, sent an appeal to M. S. Milojević, the former commander of volunteers in the Serbian-Ottoman War (1876–78), asking him to, with requesting from the Serbian government, prepare 1,000 rifles and ammunition for them, and that Milojević be appointed the commander of the rebels and that they be allowed to cross the border and start the rebellion.[43] The leaders were among the most influential in the districts of Kumanovo, Kriva Palanka, Kočani, Štip, Veles, Prilep, Bitola, Ohrid, Kičevo and Skopje.[44] The appeal was signed by Spiro Crne, Mihajlo Čakre, Dime Ristić-Šiće, Mladen Stojanović "Čakr-paša", Čerkez Ilija, Davče Trajković, and 59 other rebels and former volunteers in the Serbian army.[43] The reply from the Serbian government is unknown; it is possible that it did not reply.[43] From these intentions, only in the Poreče region, an ethnically uniform compact province, a larger result was achieved.[43] In Poreče, whole villages turned on the Ottomans.[45] Viewed of as a continuation of the Kumanovo Uprising,[46] the Brsjak Revolt began on 14 October 1880,[47] and broke out in the nahiya of Kičevo, Poreče, Bitola and Prilep.[37] The movement was active for little more than a year,[48] finally being suppressed by the Ottoman jandarma (gendarmerie).[47]

Most schools in Macedonia had disappeared by the time of the Serbo-Turkish War (1876–78). In the mid-1890s it was claimed that there were around 100 Serbian schools in Macedonia, though attendance was low. A school was opened in Skopje in 1892, but soon closed after Bulgarians complained that the required city quarters were lacking, the same happened in Kumanovo. Two new schools opened in 1893 and by 1896 the Serbian influence reached its peak but had declined by the start of the 20th century. On August 5, 1898, Dimitar Grdanov, a Serbian teacher in Ohrid, and pro-Serbian activist in Macedonia, was murdered by Metody Patchev, after which Patchev and his fellow conspirators Hristo Uzunov, Cyril Parlichev and Ivan Grupchev were arrested.[49] These were members of the pro-Bulgarian Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).

Macedonian Struggle and Balkan Wars (1903–13)

At the end of the 19th century, the liberated countries started actively to process the Christian population in European Turkey. In the beginning, there were unarmed, propagandic, cultural and likewise activities. Later, the activities would transition into a revolt against the Ottoman Empire, and between the rebel bands. Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia claimed Macedonia as legitimate owners.

Greece pointed at its Antique and Roman/Byzantine province of Macedonia. Bulgaria pointed at its holding of Macedonia during Simeon I and Asen II. Serbia pointed at its material heritage, endowments of the Nemanjić and Mrnjavčević eras, and the identity-preserved in many regions; traditions such as slava (Serbian Orthodox tradition) and linguistical bonds (see Macedonian language).[50]

In 1886, the Society of Saint Sava was formed, which aimed to aid the Serbian cause in Macedonia. Serbian consulates were opened in Skopje in 1887, Pristina in 1889, Bitola in 1889, and Prizren in 1896.

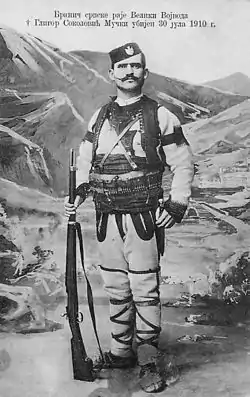

As of 1903, the Serbian Chetniks, men like Jovan Stojković Babunski, Micko Krstić, Jovan Dolgač, Gligor Sokolović, Vasilije Trbić confronted Turkish, Albanian and Bulgarian (VMRO-led) military formations together with their squads called "Četa"-mobile volunteer units strongly armed with personal weapons.[51]

The Serb Democratic League in the Ottoman Empire (Serbian: Српска демократска лига у Отоманској царевини) was an Ottoman Serb political organization established on August 13, 1908, at the First Serb Conference (August 10–13), immediately after the Young Turk Revolution. Some 26 most distinguished Serbs in the Ottoman Empire attended and Bogdan Radenković was selected to head the "Temporary Central Board of the Organization of Ottoman Serbs" in July in 1908. Bishop Vicentije Krdzić of the Serbian Orthodox Eparchy of Skopje headed the clergy and Bogdan Radenković the lay membership of the "Assembly of Ottoman Serbs in Skopje", held on Sretenje in 1909. These organizations included the Serb elite of Old Raška, Kosovo and Metohija, and Vardar Macedonia and Aegean Macedonia. It included many members of the Serbian Chetnik Organization as well. They were: Bogdan Radenković; Aleksandar Bukvić; Gligorije Elezović; Vasa Jovanović; Milan Čemerikić; Sava Stojanović; David Dimitrijević; Đorđe Hadzi-Kostić; Velimir Prelić and Jovan Šantrić.

With the founding of the Serb Democratic League, it became the first political party to represent the interests of the Serbs in the Ottoman Empire. The Serbian Democratic League sent to Thessaloniki Bogdan Radenković, Jovan Šantrić, and Đorđe Hadži-Kostić to negotiate with the Central Young Turk Board. The Serbian demands were as follows: for the three non-Muslim “ethnic groups” – Serbian, Greek and Bulgarian – to get an equal number of seats in the Ottoman Parliament. But the Young Turks refused that concept and they conditioned the electoral agreement with the Serbs with having an agreement on broader bases that would not have a national background. In 1910 as a representative of the party, he was sent to Istanbul where he urged the Turkish authorities to stop using their troops (Bashi-bazouk) to terrorize the Serbian population in Gjilan. The Sublime Porte denied the violence in Kosovo claiming that it was a fabrication. Yet to the Albanians are credited many of the outrages that have been committed to Old Serbia, where Turkish troops are alleged to have massacred more than 60,000 Christians.

The Young Turks Revolution of 1908 created slightly better conditions for the expression of Serbian cultural life in Macedonia. Serbian publishing of books, religious calendars, newspapers briefly flourished. The "Assembly of Ottoman Serbs" was held in Skoplje and Serbs had their deputies in the Ottoman parliament.

During the Balkan Wars (1912–13), Serbia liberated most of the Macedonians (called "southern Serbs") by taking over the vast land including today's North Macedonia and northern Albania (its ally Greece initially winning over the lands immediately south), much at the grievance of Bulgaria. The period from 1913 to 1914 is a period of turmoil, and the central government in Belgrade implemented plenty of unpopular measures.

Yugoslavia

In the late 19th and early 20th century the international community generally viewed the Macedonian Slavs as a regional variety of Bulgarians.[52] At the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, however, the Allies approved Serbian control of Vardar Macedonia, claiming that the Macedonian Slavs were Southern Serbs.[53] After the creation of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918), the territory of what is today North Macedonia, Kosovo, southwestern and southeastern Serbia was administratively organized into South Serbia. Although reorganized in 1922, the term continued to be used for the new administrative divisions, the Vardar Banovina and Zeta Banovina.[54]

When Bulgaria invaded southern Serbia during World War I, it regarded all who celebrated the slava as Serbs and enemies, as Bulgarians do not have the custom. For instance, when Bulgarian commander Protogerov was ordered to inflict reprisals in the east of Kumanovo for an earlier attack, and the population quickly declared as Bulgarians before the measures were taken (as to avoid punishment), his aides had the idea of asking the people who celebrated the slava; those who did were shot.[55]

During the World War II, the IMRO deported Macedonian Serbs; The Serbian community of Veles faced massive deportations, of the 25,000 Serbs of Skopje only 2,000 remained by the beginning of 1942. The IMRO was active in the deportation and punitive expeditions against ethnic Serbs.[56]

Some 120,000 Serbs were forced to emigrate to Serbia by the Yugoslav Communists after they had opted for Serbian citizenship in 1944.[57] The population of Serbs in Macedonia which did not lend itself to Tito's Macedonianization, representing compact populations in the region of Skopska Crna Gora and having significant presence in Kumanovo, Skoplje, Tetovo, and surroundings, was separated from Yugoslav Serbia. Immediately after the liberation from the occupying forces, in 1945, the requests to become a part of the newly formed federal unit of Serbia came from some regions of Macedonia in spite of the terror of the new Macedonian government. The typical example was the plea of the rural population in the Vratnica municipality, Tetovo district. In a letter to the minister for Serbia in the Government of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia the inhabitants of these villages stated: "We, the Serbs from the Vratnica municipality have never felt otherwise but as Serbs, the same as our ancestors, and it has been so for centuries. Because of that we suffered extremely during the occupation both in the last World War and in this one that ended recently. During the occupation in this war, 41 Serbs were executed by firing squads, some were Interned and there was not a single Serb between the age of 15 and 66 that was not beaten and molested to exhaustion." The inhabitants in the Vratnica municipality also complained about the new Macedonian officials and listed the main reasons such as: "In our district the administrative authorities are mostly constituted of the persons who were Fascist collaborators, the persons who welcomed the German army with delight, the persons who held religious service of thanksgiving when the German armada was victorious though the Germans never requested such things from the city dwellers." Even an example is given: during the occupation the village representative in the Vratnica municipality was Andra Hristov from Tetovo (in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia he was a clerk in the Tetovo district court, but then his surname was Serbian - Ristić), who is now said to be "...an official of the people's administration authorities in Skopje.[58]

In September 1991, shortly after the start of the Yugoslav Wars, SR Macedonia held a referendum on independence from Yugoslavia for which there was a 72% turnout of eligible voters. 95% approved independence, but Macedonia's Albanians and Serbs boycotted the referendum.[59]

North Macedonia

In 1992, Serbs of Kumanovo organized themselves in associations and political parties and held demonstrations in support of the Serbian cause in SR Bosnia and Herzegovina and SR Croatia. Serbian Radical Party sympathizers in Macedonia made an effort to establish a "Serbian Autonomous Region of Kumanovo Valley and Skopska Crna Gora". In January 1993, 500 Macedonian Serb nationalists gathered in the town of Kučevište, north of Skopje, to protest the police repression against ethnic Serbs on New Year's Eve when 13 Serbian youths were injured. Macedonian Serbs asserted they were mistreated by Macedonian authorities.[60]

The post-war years were characterized by the loss of national institutions like the proclamation of the non-recognized Macedonian Orthodox Church (MOC) in 1958–67, that would try to erase the Serbian Orthodox character of Macedonia. Several Serbian Orthodox monasteries have been seized by the MOC, however in the regions with prevailing numbers of Serbs, the Serbian Orthodox Church still has jurisdiction. Further problems between the two arose when Archbishop Jovan VI of Ohrid, the Serbian Orthodox Archbishop of Macedonia, was arrested and sentenced to prison, found Prisoner of conscience by Amnesty.[61] Jovan and other Serbian Orthodox clergymen have been physically attacked and several churches and monasteries in use by the SOC in Macedonia have been destroyed.[62] Since World War II several educational institutions in the Serbian language and common cultural centers have been closed.

Demographics

The number of Serbs in the region has fallen from the 1971 census, when they numbered 46,465 (2.85% of population). According to the 2002 census, there were 35,939 Serbs (1.78%).

Non-governmental organization estimate that the Serbs number at 100,000[63] to 200,000.[64]

| Census | Serbs | % |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 46,465 | 2.85% |

| 1981 | 44,613 | 2.3% |

| 1991 | 42,755 | 2.1% |

| 2002 | 35,939 | 1.78% |

The Serbs of North Macedonia are mostly concentrated along the northern border with Serbia. They form substantial populations in Kumanovo and Skopje. Although there is another large concentration in south-eastern Gevgelija and Dojran regions. The population with the highest percentage of Serbs is the Čučer-Sandevo municipality with 2,426 Serbs or roughly 28.6% of the population.

| Municipality | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Kumanovo municipality | 9,062 | 8.6% |

| Aerodrom municipality | 3,085 | 4.3% |

| Čučer-Sandevo municipality | 2,426 | 28.6% |

| Karpoš municipality | 2,184 | 3.7% |

| Gazi Baba municipality | 2,097 | 2.9% |

| Centar municipality | 2,037 | 4.5% |

| Gjorče Petrov municipality | 1,730 | 4.2% |

| Kisela Voda municipality | 1,426 | 2.5% |

| Butel municipality | 1,033 | 2.9% |

| Staro Nagoričane municipality | 926 | 19.1% |

| Ilinden municipality | 912 | 5.7% |

| Valandovo municipality | 630 | 5.4% |

| Negotino municipality | 627 | 3.3% |

| Čair municipality | 621 | 1% |

| Rosoman municipality | 409 | 9.9% |

| Dojran municipality | 277 | 8% |

- Villages with Serb majority

- Selemli, Bogdanci

- Marvinci, Valandovo

- Tabanovce, Kumanovo

- Karabičane, Kumanovo

- Rečica, Kumanovo

- Suševo, Kumanovo

- Tromeđa, Kumanovo

- Četirce, Kumanovo

- Staro Nagoričane, Staro Nagoričane

- Algunja, Staro Nagoričane

- Miglence, Staro Nagoričane

- Nikuljane, Staro Nagoričane

- Čučer-Sandevo, Čučer-Sandevo

- Kučevište, Čučer-Sandevo

- Villages with Serb plurality

Notable people with Serbian ancestry

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  | .jpg.webp) |  | .jpg.webp) |  |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Serbs in North Macedonia. |

References

- 2002 Macedonian Census

- Jim Bradbury, The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare, Routledge Companions to History, Routledge, 2004, ISBN 1134598475, p. 172.

- John Van Antwerp Fine, The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, University of Michigan Press, 1994, ISBN 0472082604, p. 1282.

- Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. 13 June 2013. p. 44. ISBN 978-90-04-25076-5.

In the Ottoman defters, Orthodox Christians are as a rule recorded as kâfir or gâvur (infidels) or (u)rum.

- Ив. Дуйчев, ‘Славяни и първобългари’, Известия на Института за българска история, Vols 1, 2 (1951), p. 197

- J. B. Bury (1 January 2008). History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60520-405-5.

- Cambridge Medieval Encyclopedia, Volume II.

- Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1967). Moravcsik, Gyula (ed.). De Administrando Imperio (4 ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 978-0-88402-021-9.

- Walter Emil Kaegi (27 March 2003). Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. pp. 319–. ISBN 978-0-521-81459-1.

- Andreas Nikolaou Stratos (1975). Byzantium in the Seventh Century: 642-668. Adolf M. Hakkert. ISBN 978-90-256-0748-7.

- Erdeljanovich. J. "O naseljavanju Slovena u Maloj Aziji i Siriji od VII do X veka" Glasnik geografskog drushtva vol. VI 1921 p. 189

- Ostrogorski,G. "Bizantisko-Juzhnoslovenski odnosi", Enciklopedija Jugoslavije 1,Zagreb 1955, pp. 591-599

- Fine 1991, p. 165.

- Giatzidis, Emil (2002). An Introduction to Post-Communist Bulgaria: Political, Economic and Social Transformations. Manchester University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0719060958.

- Runciman, Steven (1930). A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. London: George Bell & Sons. pp. 88–89. OCLC 832687.

- Fine 1991, p. 226.

- "Starine" 14, 1882 p. 16

- World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. 2010. pp. 1680–. ISBN 978-0-7614-7903-1.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica. 11. Encyclopædia Britannica. 1994. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-85229-591-5.

- Fine 1991, pp. 95-96.

- Georgevitch 1918, pp. 30-32.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120312141356/http://en.scientificcommons.org/41510473. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - G. Smyrnakes, "Agion Oros" (1903, Athens)

- Hélène Ahrweiler; Angeliki E. Laiou (1998). Studies on the Internal Diaspora of the Byzantine Empire. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 151–. ISBN 978-0-88402-247-3.

- Georgevitch 1918, p. 41.

- Temperley Harold William Vazeille (July 2009). History of Serbia. BiblioBazaar. pp. 57, 72. ISBN 978-1-113-20142-3.

- E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. BRILL. 1987. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- Georgevitch 1918, p. 107.

- Georgevitch 1918, pp. 91-92.

- Dragoslav Georgevich; Nikola Maric; Nicholas Moravcevich; Ljubica D. Popovich (1977). Serbian Americans and their communities in Cleveland. Cleveland State University. p. 207.

- Α. Ε. Vacalopoulos, History of Macedonia 1354-1833. Translated by Peter Megann. (Institute for Balkan studies, Θεσσαλονικη, 1973), pp. 265-266.

- Georgevitch 1918, pp. 165-167.

- Jovanović 1937, p. 236.

- Sima M. Cirkovic (15 April 2008). The Serbs. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-1-4051-4291-5.

- Georgevitch 1918, pp. 181–182.

- Vojni muzej Jugoslovenske narodne armije (1968). Fourteen Centuries of Struggle for Freedom. Belgrade: Military Museum. p. xliv.

- Georgevitch 1918, p. 183.

- Sofija Božić (1 April 2014). Istorija i geografija: susreti i prožimanja: History and geography: meetings and permeations. Институт за новију историју Србије,Географски институт "Јован Цвијић" САНУ, Институт за славистку Ран. pp. 350–. ISBN 978-86-7005-125-6.

- Jovanović 1937, p. 237.

- Hadži-Vasiljević 1928, p. 8.

- Institut za savremenu istoriju 2007, p. 87

- Босанска вила: лист за забаву, поуку и књижевност. Никола Т. Кашиковић. 1905.

... но долазимо те као Срби молити и преклињати, да прицима Тако су Турци, на бугарску доставу, 16. јуна 1878. ухватили на путу Скопље-Куманово Ристу Цветковића-Божинче, из Врања, ...

- Hadži-Vasiljević 1928, p. 9.

- Georgevitch 1918, pp. 182–183.

- Hadži-Vasiljević 1928, pp. 9–10.

- Trbić, Vasilije (1996). Memoari: 1898–1912. Kultura. p. 32.

- Hadži-Vasiljević 1928, p. 10.

- Hadži-Vasiljević 1928, p. 10, Jovanović 1937, p. 237

- Makedonija (501-512 ed.). 1995. p. 30.

- (PDF) https://web.archive.org/web/20120317181919/http://scindeks-clanci.nb.rs/data/pdf/0353-9008/2008/0353-90080825239S.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-17. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - . Srpsko Nasledje http://www.srpsko-nasledje.rs/sr-l/1998/12/article-11.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - White, George W. (2000). Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe, Geographical perspectives on the human past : Europe: Current Events. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 236. ISBN 0-8476-9809-2.

- George W. White (2000). Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-8476-9809-7.

- Čedomir Popov. Istorija srpske državnosti: Srbija u Jugoslaviji. Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti. p. 163.

Јужна Србија, која обухвата Вардарску и Зетску бановину

- Đoko M. Slijepčević (1958). The Macedonian Question: The Struggle for Southern Serbia. American Institute for Balkan Affairs. p. 77.

"Then Protogerov's aides had an idea: they asked who celebrated the slava. Those who did so were shot, since the celebration of the slava is a sign that one is a Serb: it is a custom which the Bulgars do not ...

; Gilbert in der Maur (1936). Die Jugoslawen einst und jetzt: Jugoslawiens Aussenpolitik. Günther. p. 330. - Dimitris Livanios (17 April 2008). The Macedonian Question : Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939-1949: Britain and the Southern Balkans 1939-1949. OUP Oxford. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-0-19-152872-9.

- Timothy L. Gall; Jeneen M. Hobby; Gale Group (2007). Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations: Europe. Thomson Gale. p. 422. ISBN 978-1-4144-1089-0.

- [Projekat Rastko] Slavenko Terzic: The Serbs and the Macedonian Question

- http://www.usc.edu/dept/LAS/ir/cews/database/Macedonia/macedonia.pdf

- Janusz Bugajski (1995). Ethnic Politics in Eastern Europe: A Guide to Nationality Policies, Organizations, and Parties. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1911-2.

- Amnesty International sees Jovan Vraniskovski a prisoner of conscience

- Freedom House report on Macedonia, 2006

- http://www.srpskadijaspora.info/vest.asp?id=14120. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - http://www.vidovdan.org/arhiva/print2491.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Sources

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994), The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 978-0-472-08260-5

- "О аутохтоним српским народним говорима на тлу Републике Македоније" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Slavenko Terzić (1995). "The Serbs and the Macedonian Question" (Internet ed.). Belgrade: University of Belgrade, Faculty of Geography.

- Srbi u Makedoniji i u južnoj staroj Srbiji. Štamparija Kraljevine Srbije. 1888.

- Ljubiša Doklestić (1964). Kroz historiju Makedonije: izabrani izvori. Školska knj.

- Đorđević, Dimitrije (1965). Révolutions des peuples balkaniques (in Serbian). Graficko preduzece Novi dani.

- Đurić, Veljko Đ.; Mijović, Miličko (1993). Ilustrovana istorija četničkog pokreta (in Serbian).

- Georgevitch, T. R. (1918). Macedonia. Forgotten Books. ISBN 9781440065194.

- Hadži-Vasiljević, Jovan (1928). Četnička akcija u Staroj Srbiji i Maćedoniji (in Serbian). Belgrade: Sv. Sava.

- Jovanović, Aleksa (1937). Spomenica dvadesetogodišnjice oslobodjenja Južne Srbije, 1912-1937 (in Serbian). Južna Srbija.

- "Serbia's policy towards Bulgaria and the secret convention from 1881" (PDF). Istorija. Matica srpska. 71–72: 29–.

- Radić Prvoslav (2002). "From the history of Serbian question in Macedonia: Culturological aspect". Balcanica. 32–33 (32–33): 227–252. doi:10.2298/BALC0233227R.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.