Soviet Union–United States relations

The relations between the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (1922–1991) succeeded the previous relations between the Russian Empire and the United States from 1776 to 1917 and precede today's relations between the Russian Federation and the United States that began in 1992. Full diplomatic relations between both countries were established in 1933, late due to the countries' mutual hostility. During World War II, both countries were briefly allies. At the end of the war, the first signs of post-war mistrust and hostility began to appear between the two countries, escalating into the Cold War; a period of tense hostile relations, with periods of détente.

| |

Soviet Union |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Soviet Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Moscow |

Country comparison

| Common name | Soviet Union | United States |

|---|---|---|

| Official name | Union of Soviet Socialist Republics | United States of America |

| Emblem/Seal |  |

.svg.png.webp) |

| Flag |  |

|

| Area | 22,402,200 km2 (8,649,538 sq mi) | 9,526,468 km2 (3,794,101 sq mi)[1] |

| Population | 290,938,469 (1990) | 248,709,873 (1990) |

| Population density | 13.0/km2 (33.6/sq mi) | 34/km2 (85.5/sq mi) |

| Capital | Moscow | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest metropolitan areas | Moscow | New York City |

| Government | Federal Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic | Federal presidential two-party constitutional republic |

| Political parties | Communist Party of the Soviet Union | Democratic Party Republican Party |

| Most common language | Russian | English |

| Currency | Soviet ruble | US dollar |

| GDP (nominal) | $2.659 trillion (~$9,896 per capita) | $5.79 trillion (~$24,000 per capita) |

| Intelligence agencies | Committee for State Security (KGB) | Central Intelligence Agency Federal Bureau of Investigation National Security Agency |

| Military expenditures | $290 billion (1990) | $409.7 billion (1990) |

| Army size | Soviet Army

|

US Army

|

| Navy size | Soviet Navy (1990)[2]

|

US Navy (1990)

|

| Air force size | Soviet Air Force (1990)[3]

|

US Air Force (1990)

|

| Nuclear warheads (total) | 37,000 (1990) | 10,904 (1990) |

| Economy | Communism, specifically Marxism-Leninism | Capitalism |

| Economic alliance | Comecon | European Economic Community Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| Military alliance | Warsaw Pact | North Atlantic Treaty Organization |

| Countries allied during the Cold War |

Warsaw Pact:

Soviet Republics seat in the United Nations: Baltic States as Soviet Republics: Other Soviet Socialist Republics:

Other allies:

|

NATO:

Status of the Baltic States during occupation: Other allies:

|

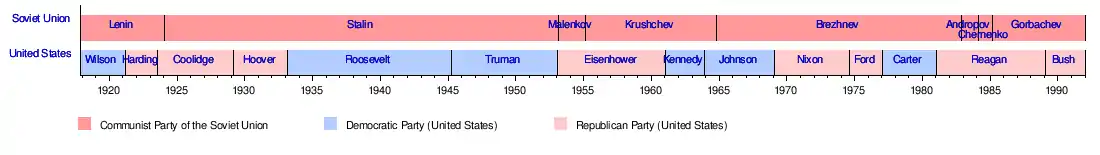

Leaders of the Soviet Union and the United States from 1917 to 1991.

History

1917–1932

After the Bolshevik takeover of Russia in the October Revolution, Vladimir Lenin withdrew Russia from the First World War, allowing Germany to reallocate troops to face the Allied forces on the Western Front and causing many in the Allied Powers to regard the new Russian government as traitorous for violating the Triple Entente terms against a separate peace.[4] Concurrently, President Woodrow Wilson became increasingly aware of the human rights violations perpetuated by the new Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, and opposed the new regime's atheism and advocacy of a command economy. He also was concerned that Marxism–Leninism would spread to the remainder of the Western world, and intended his landmark Fourteen Points partially to provide liberal democracy as an alternative worldwide ideology to Communism.[5][6]

However, President Wilson also believed that the new country would eventually transition to a progressive free-market democracy after the end of the chaos of the Russian Civil War, and that intervention against Soviet Russia would only turn the country against the United States. He likewise advocated a policy of noninterference in the war in the Fourteen Points, although he argued that the former Russian Empire's Polish territory should be ceded to the newly independent Second Polish Republic. Additionally many of Wilson's political opponents in the United States, including the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Henry Cabot Lodge, believed that an independent Ukraine should be established. Despite this the United States, as a result of the fear of Japanese expansion into Russian-held territory and their support for the Allied-aligned Czech Legion, sent a small number of troops to Northern Russia and Siberia. The United States also provided indirect aid such as food and supplies to the White Army.[4][7][5]

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 President Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, despite the objections of French President Georges Clemenceau and Italian Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino, pushed forward an idea to convene a summit at Prinkipo between the Bolsheviks and the White movement to form a common Russian delegation to the Conference. The Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, under the leadership of Leon Trotsky and Georgy Chicherin, received British and American envoys respectfully but had no intentions of agreeing to the deal due to their belief that the Conference was composed of an old capitalist order that would be swept away in a world revolution. By 1921, after the Bolsheviks gained the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, executed the Romanov imperial family, repudiated the tsarist debt, and called for a world revolution by the working class, it was regarded as a pariah nation by most of the world.[5] Beyond the Russian Civil War, relations were also dogged by claims of American companies for compensation for the nationalized industries they had invested in.[8]

Leaders of American foreign policy remain convinced that the Soviet Union was a hostile threat to American values. Republican Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes rejected recognition, telling labor union leaders that, "those in control of Moscow have not given up their original purpose of destroying existing governments wherever they can do so throughout the world."[9] Under President Calvin Coolidge, Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg warned that the Kremlin's international agency, the Communist International (Comintern) was aggressively planning subversion against other nations, including the United States, to "overthrow the existing order."[10] Herbert Hoover in 1919 warned Wilson that, "We cannot even remotely recognize this murderous tyranny without stimulating action is to radicalism in every country in Europe and without transgressing on every National ideal of our own."[11] Inside the U.S. State Department, the Division of Eastern European Affairs by 1924 was dominated by Robert F. Kelley, a zealous enemy of communism who trained a generation of specialists including George Kennan and Charles Bohlen. Kelley was convinced the Kremlin planned to activate the workers of the world against capitalism.[12]

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom and other European nations were reopening relations with Moscow, especially trade, although they remain suspicious of communist subversion, and angry at the Kremlin's repudiation of Russian debts. Outside Washington, there was some American support for renewed relationships, especially in terms of technology.[13] Henry Ford, committed to the belief that international trade was the best way to avoid warfare, used his Ford Motor Company to build a truck industry and introduce tractors into Russia. Architect Albert Kahn became a consultant for all industrial construction in the Soviet Union in 1930.[14] A few intellectuals on the left showed an interest. After 1930, a number of activist intellectuals have become members of the Communist Party USA, or fellow travelers, and drummed up support for the Soviet Union. The American labor movement was divided, with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) an anti-communist stronghold, while left-wing elements in the late 1930s formed the rival Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The CPUSA played a major role in the CIO until its members were purged beginning in 1946, and American organized labor became strongly anti-Soviet.[15]

Recognition in 1933

By 1933, old fears of Communist threats had faded, and the American business community, as well as newspaper editors, were calling for diplomatic recognition. The business community was eager for large-scale trade with the Soviet Union. The US government hoped for some repayment on the old tsarist debts, and a promise not to support subversive movements inside the U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt took the initiative, with the assistance of his close friend and advisor Henry Morgenthau, Jr. and Russian expert William Bullitt, bypassing the State Department.[16][17] Roosevelt commissioned a survey of public opinion, which at the time meant asking 1100 newspaper editors; 63 percent favored recognition of the USSR and 27 percent were opposed. Roosevelt met personally with Catholic leaders to overcome their objections. He invited Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov to Washington for a series of high-level meetings in November 1933. He and Roosevelt agreed on issues of religious freedom for Americans working in the Soviet Union. The USSR promised not to interfere in internal American affairs, and to ensure that no organization in the USSR was working to hurt the U.S. or overthrow its government by force. Both sides agreed to postpone the debt question to a later date. Roosevelt thereupon announced an agreement on resumption of normal relations.[18][19] There were few complaints about the move.[20]

However, there was no progress on the debt issue, and little additional trade. Historians Justus D. Doenecke and Mark A. Stoler note that, "Both nations were soon disillusioned by the accord."[21] Many American businessmen expected a bonus in terms of large-scale trade, but it never materialized.[22]

Roosevelt named William Bullitt as ambassador from 1933 to 1936. Bullitt arrived in Moscow with high hopes for Soviet–American relations, his view of the Soviet leadership soured on closer inspection. By the end of his tenure, Bullitt was openly hostile to the Soviet government. He remained an outspoken anti-communist for the rest of his life.[23][24]

World War II (1939–45)

Before the Germans decided to invade the Soviet Union in June 1941, relations remained strained, as the Soviet invasion of Finland, Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Soviet invasion of the Baltic states and the Soviet invasion of Poland stirred, which resulted in Soviet Union's expulsion from the League of Nations. Come the invasion of 1941, the Soviet Union entered a Mutual Assistance Treaty with the United Kingdom, and received aid from the American Lend-Lease program, relieving American-Soviet tensions, and bringing together former enemies in the fight against Nazi Germany and the Axis powers.

Though operational cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union was notably less than that between other allied powers, the United States nevertheless provided the Soviet Union with huge quantities of weapons, ships, aircraft, rolling stock, strategic materials, and food through the Lend-Lease program. The Americans and the Soviets were as much for war with Germany as for the expansion of an ideological sphere of influence. During the war, President Harry S. Truman stated that it did not matter to him if a German or a Soviet soldier died so long as either side is losing.[25]

The American Russian Cultural Association (Russian: Американо–русская культурная ассоциация) was organized in the US in 1942 to encourage cultural ties between the Soviet Union and the United States, with Nicholas Roerich as honorary president. The group's first annual report was issued the following year. The group does not appear to have lasted much past Nicholas Roerich's death in 1947.[26][27]

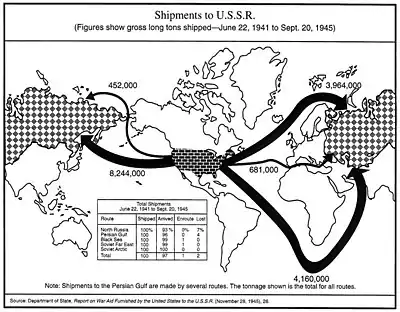

In total, the U.S. deliveries through Lend-Lease amounted to $11 billion in materials: over 400,000 jeeps and trucks; 12,000 armored vehicles (including 7,000 tanks, about 1,386[28] of which were M3 Lees and 4,102 M4 Shermans);[29] 11,400 aircraft (4,719 of which were Bell P-39 Airacobras)[30] and 1.75 million tons of food.[31]

Roughly 17.5 million tons of military equipment, vehicles, industrial supplies, and food were shipped from the Western Hemisphere to the Soviet Union, with 94 percent coming from the United States. For comparison, a total of 22 million tons landed in Europe to supply American forces from January 1942 to May 1945. It has been estimated that American deliveries to the USSR through the Persian Corridor alone were sufficient, by US Army standards, to maintain sixty combat divisions in the line.[32][33]

The United States delivered to the Soviet Union from October 1, 1941 to May 31, 1945 the following: 427,284 trucks, 13,303 combat vehicles, 35,170 motorcycles, 2,328 ordnance service vehicles, 2,670,371 tons of petroleum products (gasoline and oil) or 57.8 percent of the high-octane aviation fuel,[34] 4,478,116 tons of foodstuffs (canned meats, sugar, flour, salt, etc.), 1,911 steam locomotives, 66 diesel locomotives, 9,920 flat cars, 1,000 dump cars, 120 tank cars, and 35 heavy machinery cars. Provided ordnance goods (ammunition, artillery shells, mines, assorted explosives) amounted to 53 percent of total domestic production.[34] One item typical of many was a tire plant that was lifted bodily from the Ford's River Rouge Plant and transferred to the USSR. The 1947 money value of the supplies and services amounted to about eleven billion dollars.[35]

Memorandum for the President's Special Assistant Harry Hopkins, Washington, D.C., 10 August 1943:

In War II Russia occupies a dominant position and is the decisive factor looking toward the defeat of the Axis in Europe. While in Sicily the forces of Great Britain and the United States are being opposed by 2 German divisions, the Russian front is receiving attention of approximately 200 German divisions. Whenever the Allies open a second front on the Continent, it will be decidedly a secondary front to that of Russia; theirs will continue to be the main effort. Without Russia in the war, the Axis cannot be defeated in Europe, and the position of the United Nations becomes precarious. Similarly, Russia’s post-war position in Europe will be a dominant one. With Germany crushed, there is no power in Europe to oppose her tremendous military forces.[36]

Cold War (1947–91)

| |

United States |

Soviet Union |

|---|---|

The end of World War II saw the resurgence of previous divisions between the two nations. The expansion of communist influence into Eastern Europe following Germany's defeat worried the liberal free market economies of the West, particularly the United States, which had established virtual economic and political primacy in Western Europe. The two nations promoted two opposing economic and political ideologies and the two nations competed for international influence along these lines. This protracted a geopolitical, ideological, and economic struggle—lasting from the announcement of the Truman Doctrine on March 12, 1947 until the dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991—is known as the Cold War, a period of nearly 45 years.

The Soviet Union detonated its first nuclear weapon in 1949, ending the United States' monopoly on nuclear weapons. The United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a conventional and nuclear arms race that persisted until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Andrei Gromyko was Minister of Foreign Affairs of the USSR, and is the longest-serving foreign minister in the world.

After Germany's defeat, the United States sought to help its Western European allies economically with the Marshall Plan. The United States extended the Marshall Plan to the Soviet Union, but under such terms, the Americans knew the Soviets would never accept, namely the acceptance of, what the Soviets viewed as, a bourgeoisie democracy, not characteristic of Stalinist communism. With its growing influence on Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union sought to counter this with the Comecon in 1949, which essentially did the same thing, though was more an economic cooperation agreement instead of a clear plan to rebuild. The United States and its Western European allies sought to strengthen their bonds and spite the Soviet Union. They accomplished this most notably through the formation of NATO which was essentially a military agreement. The Soviet Union countered with the Warsaw Pact, which had similar results with the Eastern Bloc.

Détente

Détente began in 1969, as a core element of the foreign policy of president Richard Nixon and his top advisor Henry Kissinger. They wanted to end the containment policy and gain friendlier relations with the USSR and China. Those two were rivals and Nixon expected they would go along with Washington as to not give the other rival an advantage. One of Nixon's terms is that both nations had to stop helping North Vietnam in the Vietnam War, which they did. Nixon and Kissinger promoted greater dialogue with the Soviet government, including regular summit meetings and negotiations over arms control and other bilateral agreements. Brezhnev met with Nixon at summits in Moscow in 1972, in Washington in 1973, and, again in Moscow in 1974. They became personal friends.[37][38] Détente was known in Russian as разрядка (razryadka, loosely meaning "relaxation of tension").[39]

The period was characterized by the signing of treaties such as SALT I and the Helsinki Accords. Another treaty, START II, was discussed but never ratified by the United States. There is still ongoing debate amongst historians as to how successful the détente period was in achieving peace.[40][41]

After the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, the two superpowers agreed to install a direct hotline between Washington D.C. and Moscow (the so-called red telephone), enabling leaders of both countries to quickly interact with each other in a time of urgency, and reduce the chances that future crises could escalate into an all-out war. The U.S./USSR détente was presented as an applied extension of that thinking. The SALT II pact of the late 1970s continued the work of the SALT I talks, ensuring further reduction in arms by the Soviets and by the U.S. The Helsinki Accords, in which the Soviets promised to grant free elections in Europe, has been called a major concession to ensure peace by the Soviets.

Détente ended after the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, which led to the United States boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. Ronald Reagan's election as president in 1980, based in large part on an anti-détente campaign,[42] marked the close of détente and a return to Cold War tensions. In his first press conference, President Reagan said "Détente's been a one-way street that the Soviet Union has used to pursue its aims."[43] Following this, relations turned increasingly sour with the unrest in Poland,[44][45] end of the SALT II negotiations, and the NATO exercise in 1983 that brought the superpowers almost on the brink of nuclear war.[46]

End of Détente

The period of détente ended after the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan, which led to the United States boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. Ronald Reagan's election as president in 1980 was further based in large part on an anti-détente campaign.[42] In his first press conference, President Reagan said "Détente's been a one-way street that the Soviet Union has used to pursue its aims."[43] Following this, relations turned increasingly sour with the unrest in Poland,[44][45] end of the SALT II negotiations, and the NATO exercise in 1983 that brought the superpowers almost on the brink of nuclear war.[46] The United States, Pakistan, and their allies supported the rebels. To punish Moscow, President Jimmy Carter imposed a grain embargo. This hurt American farmers more than it did the Soviet economy, and President Ronald Reagan resumed sales in 1981. Other nations sold their own grain to the USSR, and the Soviets had ample reserve stocks and a good harvest of their own.[47]

Reagan attacks "Evil Empire"

Reagan escalated the Cold War, accelerating a reversal from the policy of détente which had begun in 1979 after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[48] Reagan feared that the Soviet Union had gained a military advantage over the United States, and the Reagan administration hoped to that heightened military spending would grant the U.S. military superiority and weaken the Soviet economy.[49] Reagan ordered a massive buildup of the United States Armed Forces, directing funding to the B-1 Lancer bomber, the B-2 Spirit bomber, cruise missiles, the MX missile, and the 600-ship Navy.[50] In response to Soviet deployment of the SS-20, Reagan oversaw NATO's deployment of the Pershing missile in West Germany.[51] The president also strongly denounced the Soviet Union and Communism in moral terms, describing the Soviet Union an "evil empire."[52]

End of the Cold War

At the Malta Summit of December 1989, both the leaders of the United States and the Soviet Union declared the Cold War over. In 1991, the two countries were partners in the Gulf War against Iraq, a longtime Soviet ally. On 31 July 1991, the START I treaty cutting the number of deployed nuclear warheads of both countries was signed by Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and U.S. President George Bush. However, many consider the Cold War to have truly ended in late 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

See also

References

- "United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- "Soviet Navy Ships - 1945-1990 - Cold War". GlobalSecurity.org.

- "Arsenal of Airpower". the99percenters.net. March 13, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2016 – via Washington Post.

- Fic, Victor M (1995), The Collapse of American Policy in Russia and Siberia, 1918, Columbia University Press, New York

- MacMillan, Margaret, 1943- (2003). Paris 1919 : six months that changed the world. Holbrooke, Richard (First U.S. ed.). New York: Random House. pp. 63–82. ISBN 0-375-50826-0. OCLC 49260285.

- "Fourteen Points | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)". encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net. Retrieved 2020-02-08.

- "Fourteen Points | Text & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-02-07.

- Donald E. Davis and Eugene P. Trani (2009). Distorted Mirrors: Americans and Their Relations with Russia and China in the Twentieth Century. University of Missouri Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780826271891.

- Douglas Little, "Anti-Bolshevism and American Foreign Policy, 1919-1939" American Quarterly (1983) 35#4 pp 376-390 at p 378.

- Little, p 178

- Little, p 378-79.

- Little, p 379.

- Kendall E. Bailes, "The American Connection: Ideology and the Transfer of American Technology to the Soviet Union, 1917–1941." Comparative Studies in Society and History 23#3 (1981): 421-448.

- Dana G. Dalrymple, "The American tractor comes to Soviet agriculture: The transfer of a technology." Technology and Culture 5.2 (1964): 191-214.

- Michael J. Heale, American anti-communism: combating the enemy within, 1830-1970 (1990).

- Robert Paul Browder, The origins of Soviet-American diplomacy (1953) pp 99-127 Online free to borrow

- Robert P. Browder, "The First Encounter: Roosevelt and the Russians, 1933" United States Naval Institute proceedings (May 1957) 83#5 pp 523-32.

- Robert Dallek (1979). Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932-1945: With a New Afterword. Oxford UP. pp. 78–81. ISBN 9780195357059.

- Smith 2007, pp. 341–343.

- Paul F. Boller (1996). Not So!: Popular Myths about America from Columbus to Clinton. Oxford UP. pp. 110–14. ISBN 9780195109726.

- Justus D. Doenecke and Mark A. Stoler (2005). Debating Franklin D. Roosevelt's Foreign Policies, 1933-1945. pp. 18. 121. ISBN 9780847694167.

- Joan H. Wilson, "American Business and the Recognition of the Soviet Union." Social Science Quarterly (1971): 349-368. in JSTOR

- Will Brownell and Richard Billings, So Close to Greatness: The Biography of William C. Bullitt (1988)

- Edward Moore Bennett, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the search for security: American-Soviet relations, 1933-1939 (1985).

- "National Affairs: Anniversary Remembrance". Time. Time magazine. 2 July 1951. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- "American-Russian Cultural Association". roerich-encyclopedia. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- "Annual Report". onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- Zaloga (Armored Thunderbolt) p. 28, 30, 31

- Lend-Lease Shipments: World War II, Section IIIB, Published by Office, Chief of Finance, War Department, 31 December 1946, p. 8.

- Hardesty 1991, p. 253

- World War II The War Against Germany And Italy, US Army Center Of Military History, page 158.

- "The five Lend-Lease routes to Russia". Engines of the Red Army. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Motter, T.H. Vail (1952). The Persian Corridor and Aid to Russia. Center of Military History. pp. 4–6. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- Weeks 2004, p. 9

- Deane, John R. 1947. The Strange Alliance, The Story of Our Efforts at Wartime Co-operation with Russia. The Viking Press.

- "The Executive of the Presidents Soviet Protocol Committee (Burns) to the President's Special Assistant (Hopkins)". www.history.state.gov. Office of the Historian.

- Donald J. Raleigh, "'I Speak Frankly Because You Are My Friend': Leonid Ilich Brezhnev’s Personal Relationship with Richard M. Nixon." Soviet & Post-Soviet Review (2018) 45#2 pp 151-182.

- Craig Daigle (2012). The Limits of Detente: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1969-1973. Yale UP. pp. 273–78. ISBN 978-0300183344.

- Barbara Keys, "Nixon/Kissinger and Brezhnev." Diplomatic History 42.4 (2018): 548-551.

- "The Rise and Fall of Détente, Professor Branislav L. Slantchev, Department of Political Science, University of California – San Diego 2014" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- Nuti, Leopoldo (11 November 2008). The Crisis of Détente in Europe. ISBN 9780203887165. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- "Ronald Reagan, radio broadcast on August 7th, 1978" (PDF). Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- "Ronald Reagan. January 29, 1981 press conference". Presidency.ucsb.edu. 29 January 1981. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- "Detente Wanes as Soviets Quarantine Satellites from Polish Fever". Washington Post. 1980-10-19.

- Simes, Dimitri K. (1980). "The Death of Detente?". International Security. 5 (1): 3–25. doi:10.2307/2538471. JSTOR 2538471. S2CID 154098316.

- "The Cold War Heats up – New Documents Reveal the "Able Archer" War Scare of 1983". 2013-05-20.

- Robert L. Paarlberg, "Lessons of the grain embargo." Foreign Affairs 59.1 (1980): 144-162. online

- "Towards an International History of the War in Afghanistan, 1979–89". The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. 2002. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Douglas C. Rossinow, The Reagan Era: A History of the 1980s (2015). pp. 66–67

- James Patterson, Restless Giant: The United States from Watergate to Bush v. Gore (2005). p. 200

- Patterson, pp. 205

- Rossinow, p. 67

Further reading

- Bennett, Edward M. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Search for Security: American-Soviet Relations, 1933-1939 (1985)

- Bennett, Edward M. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Search for Victory: American-Soviet Relations, 1939-1945 (1990).

- Browder, Robert P. "The First Encounter: Roosevelt and the Russians, 1933" United States Naval Institute proceedings (May 1957) 83#5 pp 523–32.

- Browder, Robert P. The origins of Soviet-American diplomacy (1953) pp 99–127 Online free to borrow

- Cohen, Warren I. The Cambridge History of American Foreign Relations: Vol. IV: America in the Age of Soviet Power, 1945-1991 (1993).

- Crockatt, Richard. The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in world politics, 1941-1991 (1995).

- Diesing, Duane J. Russia and the United States: Future Implications of Historical Relationships (No. Au/Acsc/Diesing/Ay09. Air Command And Staff Coll Maxwell Afb Al, 2009). online

- Dunbabin, J.P.D. International Relations since 1945: Vol. 1: The Cold War: The Great Powers and their Allies (1994).

- Fike, Claude E. "The Influence of the Creel Committee and the American Red Cross on Russian-American Relations, 1917-1919." Journal of Modern History 31#2 (1959): 93-109. online.

- Foglesong, David S. The American mission and the 'Evil Empire': the crusade for a 'Free Russia' since 1881 (2007).

- Gaddis, John Lewis. Russia, the Soviet Union, and the United States (2nd ed. 1990) online free to borrow covers 1781-1988

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1941-1947 (2000).

- Garthoff, Raymond L. Détente and confrontation: American-Soviet relations from Nixon to Reagan (2nd ed. 1994) In-depth scholarly history covers 1969 to 1980. online free to borrow

- Garthoff, Raymond L. The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War (1994), In-depth scholarly history, 1981 to 1991, online

- Glantz, Mary E. FDR and the Soviet Union: the President's battles over foreign policy (2005).

- LaFeber, Walter. America, Russia, and the Cold War 1945-2006 (2008). online 1984 edition

- Leffler, Melvyn P. The Specter of Communism: The United States and the Origins of the Cold War, 1917-1953 (1994).

- Lovenstein, Meno. American Opinion Of Soviet Russia (1941) online

- Nye, Joseph S. ed. The making of America's Soviet policy (1984)

- Saul, Norman E. Distant Friends: The United States and Russia, 1763-1867 (1991)

- Saul, Norman E. Concord and Conflict: The United States and Russia, 1867-1914 (1996)

- Saul, Norman E. War and Revolution: The United States and Russia, 1914-1921 (2001)

- Saul, Norman E. Friends or foes? : the United States and Soviet Russia, 1921-1941 (2006) online free to borrow

- Saul, Norman E. The A to Z of United States-Russian/Soviet Relations (2010)

- Saul, Norman E. Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Foreign Policy (2014).

- Sibley, Katherine A. S. "Soviet industrial espionage against American military technology and the US response, 1930–1945." Intelligence and National Security 14.2 (1999): 94-123.

- Sokolov, Boris V. "The role of lend‐lease in Soviet military efforts, 1941–1945." Journal of Slavic Military Studies 7.3 (1994): 567–586.

- Stoler, Mark A. Allies and Adversaries: The Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Grand Alliance, and US Strategy in World War II. (UNC Press, 2003).

- Taubman, William. Gorbachev (2017) excerpt

- Taubman, William. Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2012), Pulitzer Prize

- Taubman, William. Stalin’s American Policy: From Entente to Détente to Cold War (1982).

- Thomas, Benjamin P.. Russo-American Relations: 1815-1867 (1930).

- Trani, Eugene P. "Woodrow Wilson and the decision to intervene in Russia: a reconsideration." Journal of Modern History 48.3 (1976): 440–461. online

- Unterberger, Betty Miller. "Woodrow Wilson and the Bolsheviks: The 'Acid Test' of Soviet–American Relations." Diplomatic History 11.2 (1987): 71–90. online

- White, Christine A. British and American Commercial Relations with Soviet Russia, 1918-1924 (UNC Press, 2017).

- Zubok, Vladislav M. A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev (1209)