TRAPPIST-1

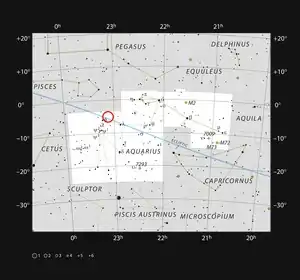

TRAPPIST-1, also designated 2MASS J23062928-0502285,[11] is an ultra-cool red dwarf star[12][13] with a radius slightly larger than the planet Jupiter, while having 84 times Jupiter's mass. It is about 40 light-years (12 pc) from the Sun in the constellation Aquarius.[14][15] Seven temperate terrestrial planets have been detected orbiting it, more than any other planetary system except Kepler-90.[16][17] A study released in May 2017 suggests that the stability of the system is not particularly surprising if one considers how the planets migrated to their present orbits through a protoplanetary disk.[18][19]

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Aquarius |

| Right ascension | 23h 06m 29.283s[1] |

| Declination | −05° 02′ 28.59″[1] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | Main sequence |

| Spectral type | M8V[2] M8.2V[note 1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 18.798±0.082[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (R) | 16.466±0.065[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (I) | 14.024±0.115[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (J) | 11.354±0.022[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (H) | 10.718±0.021[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (K) | 10.296±0.023[1] |

| V−R color index | 2.332 |

| R−I color index | 2.442 |

| J−H color index | 0.636 |

| J−K color index | 1.058 |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −54±2[2] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 922.1±1.8[2] mas/yr Dec.: −471.9±1.8[2] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 80.451 ± 0.12[3][4] mas |

| Distance | 40.54 ± 0.06 ly (12.43 ± 0.02 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 18.4±0.1 |

| Details | |

| Mass | 0.0898±0.0023[3] M☉ |

| Radius | 0.1192±0.0013[5] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 0.000553±0.000018[3] L☉ |

| Luminosity (visual, LV) | 0.00000373[note 2] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | ≈5.227[note 3][6] cgs |

| Temperature | 2566±26[5] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | 0.04±0.08[7] dex |

| Rotation | 3.295±0.003 days[8] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 6[9] km/s |

| Age | 7.6±2.2[10] Gyr |

| Other designations | |

2MASS J23062928-0502285, 2MASSI J2306292-050227, 2MASSW J2306292-050227, 2MUDC 12171 | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

| Exoplanet Archive | data |

| Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia | data |

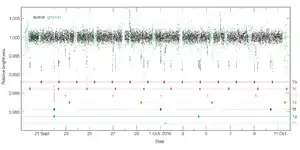

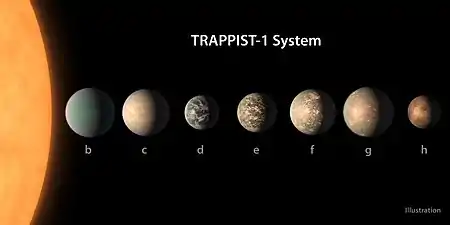

A team of Belgian astronomers first discovered three Earth-sized planets orbiting the star in 2015. A team led by Michaël Gillon at the University of Liège in Belgium detected the planets using transit photometry with the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) at the La Silla Observatory in Chile and the Observatoire de l'Oukaïmeden in Morocco.[20][13][21] On 22 February 2017, astronomers announced four such additional exoplanets. This work used the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope at Paranal, amongst others, and brought the total of planets to seven, of which at least three (e, f, and g) are considered to be within its habitable zone.[13][22][23] All could be habitable as they may have liquid water somewhere on their surface.[24][25][26] Depending on definition, up to six could be in the optimistic habitable zone (c, d, e, f, g, and h), with estimated equilibrium temperatures of 170 to 330 K (−103 to 57 °C; −154 to 134 °F).[7] In November 2018, researchers determined that planet e is the most likely Earth-like ocean world and "would be an excellent choice for further study with habitability in mind."[27]

Discovery and nomenclature

The star at the center of the system was discovered in 1999 during the Two Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS).[28][29] It was entered in the subsequent catalog with the designation "2MASS J23062928-0502285". The numbers refer to the right ascension and declination of the star's position in the sky and the "J" refers to the Julian Epoch.

The system was later studied by a team at the University of Liège, who made their initial observations using the TRAPPIST–South telescope from September to December 2015 and published their findings in the May 2016 issue of the journal Nature.[20][12] The backronym pays homage to the Catholic Christian religious order of Trappists and to the Trappist beer it produces (primarily in Belgium), which the astronomers used to toast their discovery.[30][31] Since the star hosted the first exoplanets discovered by this telescope, the discoverers accordingly designated it as "TRAPPIST-1".

The planets are designated in the order of their discovery, beginning with b for the first planet discovered, c for the second and so on.[32] Three planets around TRAPPIST-1 were first discovered and designated b, c and d in order of increasing orbital periods,[12] and the second batch of discoveries was similarly designated e to h.

Stellar characteristics

TRAPPIST-1 is an ultra-cool dwarf star of spectral class M8.0±0.5 that is approximately 8% the mass of and 11% the radius of the Sun. Although it is slightly larger than Jupiter, it is about 84 times more massive.[33][12] High-resolution optical spectroscopy failed to reveal the presence of lithium,[34] suggesting it is a very low-mass main-sequence star, which is fusing hydrogen and has depleted its lithium, i.e., a red dwarf rather than a very young brown dwarf.[12] It has a temperature of 2,511 K (2,238 °C; 4,060 °F),[7] and its age has been estimated to be approximately 7.6±2.2 Gyr.[10] In comparison, the Sun has a temperature of 5,778 K (5,505 °C; 9,941 °F)[35] and an age of about 4.6 Gyr.[36] Observations with the Kepler K2 extension for a total of 79 days revealed starspots and infrequent weak optical flares at a rate of 0.38 per day (30-fold less frequent than for active M6–M9 dwarfs); a single strong flare appeared near the end of the observation period. The observed flaring activity possibly changes the atmospheres of the orbiting planets on a regular basis, making them less suitable for life.[8] The star has a rotational period of 3.3 days.[8][37]

High-resolution speckle images of TRAPPIST-1 were obtained and revealed that the M8 star has no companions with a luminosity equal to or brighter than a brown dwarf.[38] This determination that the host star is single confirms that the measured transit depths for the orbiting planets provide a true value for their radii, thus proving that the planets are indeed Earth-sized.

Owing to its low luminosity, the star has the ability to live for up to 12 trillion years.[39] It is metal-rich, with a metallicity ([Fe/H]) of 0.04,[7] or 109% the solar amount. Its luminosity is 0.05% of that of the Sun (L☉), most of which is emitted in the infrared spectrum, and with an apparent magnitude of 18.80 it is not visible with basic amateur telescopes from the Earth.

Planetary system

On 22 February 2017, astronomers announced that the planetary system of this star is composed of seven temperate terrestrial planets, of which five (b, c, e, f and g) are similar in size to Earth, and two (d and h) are intermediate in size between Mars and Earth.[40] At least three of the planets (e, f and g) orbit within the habitable zone.[40][41][23][42]

The orbits of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system are very flat and compact. All seven of TRAPPIST-1's planets orbit much closer than Mercury orbits the Sun. Except for b, they orbit farther than the Galilean satellites do around Jupiter,[43] but closer than most of the other moons of Jupiter. The distance between the orbits of b and c is only 1.6 times the distance between the Earth and the Moon. The planets should appear prominently in each other's skies, in some cases appearing several times larger than the Moon appears from Earth.[42] A year on the closest planet passes in only 1.5 Earth days, while the seventh planet's year passes in only 18.8 days.[40][37]

The planets pass so close to one another that gravitational interactions are significant, and their orbital periods are nearly resonant. In the time the innermost planet completes eight orbits, the second, third, and fourth planets complete five, three, and two.[44] The gravitational tugging also results in transit-timing variations (TTVs), ranging from under a minute to over 30 minutes, which allowed the investigators to calculate the masses of all but the outermost planet. The total mass of the six inner planets is approximately 0.02% the mass of TRAPPIST-1, a fraction similar to that for the Galilean satellites to Jupiter, and an observation suggestive of a similar formation history. The densities of the planets range from ~0.60 to ~1.17 times that of Earth (ρ⊕, 5.51 g/cm3), indicating predominantly rocky compositions. The uncertainties are too large to indicate whether a substantial component of volatiles is also included, except in the case of f, where the value (0.60±0.17 ρ⊕) "favors" the presence of a layer of ice and/or an extended atmosphere.[40] Speckle imaging excludes all possible stellar and brown dwarf companions.[45]

On 31 August 2017, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope reported the first evidence of possible water content on the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets.[46][47]

Between 18 February and 27 March 2017, a team of astronomers used the Spitzer Space Telescope to observe TRAPPIST-1 to refine the orbital and physical parameters of the seven planets using updated parameters for the star. Their results were published on 9 January 2018. Although no new mass estimates were given, the team managed to refine the orbital parameters and radii of the planets within a very small error margin. In addition to updated planetary parameters, the team also found evidence for a large, hot atmosphere around the innermost planet.[7]

On 5 February 2018, a collaborative study by an international group of scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope, the Kepler Space Telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope, and the ESO's SPECULOOS telescope released the most accurate parameters for the TRAPPIST-1 system yet.[48] They were able to refine the masses of the seven planets to a very small error margin, allowing the density, surface gravity, and composition of the planets to be accurately determined. The planets range in mass from about 0.3 M⊕ to 1.16 M⊕, with densities from 0.62 ρ⊕ (3.4 g/cm3) to 1.02 ρ⊕ (5.6 g/cm3). Planets c and e are almost entirely rocky, while b, d, f, g, and h have a layer of volatiles in the form of either a water shell, an ice shell, or a thick atmosphere. Planets c, d, e, and f lack hydrogen-helium atmospheres. Planet g was also observed, but there was not enough data to firmly rule out a hydrogen atmosphere. Planet d might have a liquid water ocean comprising about 5% of its mass—for comparison, Earth's water content is < 0.1%—while if f and g have water layers, they are likely frozen. Planet e has a slightly higher density than Earth, indicating a terrestrial rock and iron composition. Atmospheric modeling suggests the atmosphere of b is likely to be over the runaway greenhouse limit with an estimated 101 to 104 bar of water vapor.[49][50]

Stellar spectrum study, performed in early 2020, has revealed the TRAPPIST-1 star rotational axis is well aligned with the plane of planetary orbits. The stellar obliquity was found to be 19+13

−15 degrees.[51]

Planetary system data charts

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity[49] | Inclination[7][40] | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 1.374±0.069 M⊕ | 0.01154±0.0001 | 1.51088432±0.00000015 | 0.00622±0.00304 | 89.56±0.23° | 1.116+0.014 −0.012 R⊕ |

| c | 1.308±0.056 M⊕ | 0.01580±0.00013 | 2.42179346±0.00000023 | 0.00654±0.00188 | 89.70±0.18° | 1.097+0.014 −0.012 R⊕ |

| d | 0.388±0.012 M⊕ | 0.02227±0.00019 | 4.04978035±0.00000256 | 0.00837±0.00093 | 89.89+0.08 −0.15° |

0.778+0.011 −0.010 R⊕ |

| e | 0.692±0.022 M⊕ | 0.02925±0.00025 | 6.09956479±0.00000178 | 0.00510±0.00058 | 89.736+0.053 −0.066° |

0.920+0.013 −0.012 R⊕ |

| f | 1.039±0.031 M⊕ | 0.03849±0.00033 | 9.20659399±0.00000212 | 0.01007±0.00068 | 89.719+0.026 −0.039° |

1.045+0.013 −0.012 R⊕ |

| g | 1.321±0.038 M⊕ | 0.04683±0.0004 | 12.3535557±0.00000341 | 0.00208±0.00058 | 89.721+0.019 −0.026° |

1.129+0.015 −0.013 R⊕ |

| h | 0.326±0.020 M⊕ | 0.06189±0.00053 | 18.7672745±0.00001876 | 0.00567±0.00121 | 89.796±0.023° | 0.775±0.014 R⊕ |

| Companion (in order from star) |

Stellar flux[5] (⊕) |

Temperature[3] (equilibrium, assumes null Bond albedo) |

Surface gravity[5] (⊕) |

Approximate orbital resonance ratio (wrt planet b) |

Approximate orbital resonance ratio (wrt next planet inwards) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 4.153±0.16 | 397.6 ± 3.8 K (124.45 ± 3.80 °C; 256.01 ± 6.84 °F) ≥1,400 K (1,130 °C; 2,060 °F) (atmosphere) 750–1,500 K (477–1,227 °C; 890–2,240 °F) (surface)[49] |

1.102±0.052 | 1:1 | 1:1 |

| c | 2.214±0.085 | 339.7 ± 3.3 K (66.55 ± 3.30 °C; 151.79 ± 5.94 °F) | 1.086±0.043 | 5:8 | 5:8 |

| d | 1.115±0.043 | 286.2 ± 2.8 K (13.05 ± 2.80 °C; 55.49 ± 5.04 °F) | 0.624±0.019 | 3:8 | 3:5 |

| e | 0.646±0.025 | 249.7 ± 2.4 K (−23.45 ± 2.40 °C; −10.21 ± 4.32 °F) | 0.817±0.024 | 1:4 | 2:3 |

| f | 0.373±0.014 | 217.7 ± 2.1 K (−55.45 ± 2.10 °C; −67.81 ± 3.78 °F) | 0.851±0.024 | 1:6 | 2:3 |

| g | 0.252±0.0097 | 197.3 ± 1.9 K (−75.85 ± 1.90 °C; −104.53 ± 3.42 °F) | 1.035±0.026 | 1:8 | 3:4 |

| h | 0.144±0.0055 | 171.7 ± 1.7 K (−101.45 ± 1.70 °C; −150.61 ± 3.06 °F) | 0.570±0.038 | 1:12 | 2:3 |

Orbital near-resonance

The orbital motions of the TRAPPIST-1 planets form a complex chain with three-body Laplace-type resonances linking every member. The relative orbital periods (proceeding outward) approximate whole integer ratios of 24/24, 24/15, 24/9, 24/6, 24/4, 24/3, and 24/2, respectively, or nearest-neighbor period ratios of about 8/5, 5/3, 3/2, 3/2, 4/3, and 3/2 (1.603, 1.672, 1.506, 1.509, 1.342, and 1.519). This represents the longest known chain of near-resonant exoplanets, and is thought to have resulted from interactions between the planets as they migrated inward within the residual protoplanetary disk after forming at greater initial distances.[40][37]

Most sets of orbits similar to the set found at TRAPPIST-1 are unstable, causing one planet to come within the Hill sphere of another or to be thrown out. But it has been found that there is a way for a system to migrate into a fairly stable state through damping interactions with, for example, a protoplanetary disk. After this, tidal forces can give the system a long-term stability.[18]

The tight correspondence between whole number ratios in orbital resonances and in music theory has made it possible to convert the system's motion into music.[19][52]

Formation of the planetary system

According to Ormel et al. previous models of planetary formation do not explain the formation of the highly compact TRAPPIST-1 system. Formation in place would require an unusually dense disk and would not readily account for the orbital resonances. Formation outside the frost line does not explain the planets' terrestrial nature or Earth-like masses. The authors proposed a new scenario in which planet formation starts at the frost line where pebble-size particles trigger streaming instabilities, then protoplanets quickly mature by pebble accretion. When the planets reach Earth mass they create perturbations in the gas disk that halt the inward drift of pebbles causing their growth to stall. The planets are transported by Type I migration to the inner disk, where they stall at the magnetospheric cavity and end up in mean motion resonances.[53] This scenario predicts the planets formed with significant fractions of water, around 10%, with the largest initial fractions of water on the innermost and outermost planets.[54]

Tidal locking

It is suggested that all seven planets are likely to be tidally locked into a so-called synchronous spin state (one side of each planet permanently facing the star),[40] making the development of life there much more challenging.[16] A less likely possibility is that some may be trapped in a higher-order spin-orbit resonance.[40] Tidally locked planets would typically have very large temperature differences between their permanently lit day sides and their permanently dark night sides, which could produce very strong winds circling the planets. The best places for life may be close to the mild twilight regions between the two sides, called the terminator line. Another possibility is that the planets may be pushed into effectively non-synchronous spin states due to strong mutual interactions among the seven planets, resulting in more complete stellar coverage over the surface of the planets.[55]

Tidal heating

Tidal heating is predicted to be significant: all planets except f and h are expected to have a tidal heat flux greater than Earth's total heat flux.[37]

With the exception of planet c, all of the planets have densities low enough to indicate the presence of significant H

2O in some form. Planets b and c experience enough heating from planetary tides to maintain magma oceans in their rock mantles; planet c may have eruptions of silicate magma on its surface. Tidal heat fluxes on planets d, e, and f are lower, but are still twenty times higher than Earth's mean heat flow. Planets d and e are the most likely to be habitable. Planet d avoids the runaway greenhouse state if its albedo is ≳ 0.3.[56]

Possible effects of strong X-ray and extreme UV irradiation of the system

Bolmont et al. modelled the effects of predicted far ultraviolet (FUV) and extreme ultraviolet (EUV/XUV) irradiation of planets b and c by TRAPPIST-1. Their results suggest that the two planets may have lost as much as 15 Earth oceans of water (although the actual loss would probably be lower), depending on their initial water contents. Nonetheless, they may have retained enough water to remain habitable, and a planet orbiting further out was predicted to lose much less water.[26]

However, a subsequent XMM-Newton X-ray study by Wheatley et al. found that the star emits X-rays at a level comparable to our own much larger Sun, and extreme ultraviolet radiation at a level 50-fold stronger than assumed by Bolmont et al. The authors predicted this would significantly alter the primary and perhaps secondary atmospheres of close-in, Earth-sized planets spanning the habitable zone of the star. The publication noted that these levels "neglected the radiation physics and hydrodynamics of the planetary atmosphere" and could be a significant overestimate. Indeed, the XUV stripping of a very thick hydrogen and helium primary atmosphere might actually be required for habitability. The high levels of XUV would also be expected to make water retention on planet d less likely than predicted by Bolmont et al., though even on highly irradiated planets it might remain in cold traps at the poles or on the night sides of tidally locked planets.[57]

If a dense atmosphere like Earth's, with a protective ozone layer, exists on planets in the habitable zone of TRAPPIST-1, UV surface environments would be similar to present-day Earth. However, an anoxic atmosphere would allow more UV to reach the surface, making surface environments hostile to even highly UV-tolerant terrestrial extremophiles. If future observations detect ozone on one of the TRAPPIST-1 planets, it would be a prime candidate to search for surface life.[58]

Spectroscopy of planetary atmospheres

Because of the system's relative proximity, the small size of the primary and the orbital alignments that produce daily transits,[60] the atmospheres of TRAPPIST-1's planets are favorable targets for transmission spectroscopy investigation.[61]

The combined transmission spectrum of planets b and c, obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope, rules out a cloud-free hydrogen-dominated atmosphere for each planet, so they are unlikely to harbor an extended gas envelope, unless it is cloudy out to high altitudes. Other atmospheric structures, from a cloud-free water-vapor atmosphere to a Venus-like atmosphere, remain consistent with the featureless spectrum.[62]

Another study hinted at the presence of hydrogen exospheres around the two inner planets with exospheric discs extending up to seven times the planets' radii.[63]

In a paper by an international collaboration using data from space and ground-based telescopes, it was found that planets c and e likely have largely rocky interiors, and that b is the only planet above the runaway green-house limit, with pressures of water vapour of the order of 101 to 104 bar.[49]

Observations by future telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope or European Extremely Large Telescope, will be able to assess the greenhouse gas content of the atmospheres, allowing better estimation of surface conditions. They may also be able to detect biosignatures like ozone or methane in the atmospheres of these planets, if life is present there.[14][64][65][66] As of 2020, the TRAPPIST-1 is considered a most promising target for transmission spectroscopy using the James Webb Space Telescope.[67]

Habitability and possibility of life

Impact of stellar activity on habitability

The K2 observations of Kepler revealed several flares on the host star. The energy of the strongest event was comparable to the Carrington event, one of the strongest flares seen on the Sun. As the planets in TRAPPIST-1 system orbit much closer to their host star than Earth, such eruptions could cause 10–10000 times stronger magnetic storms than the most powerful geomagnetic storms on Earth. Beside the direct harm caused by the radiation associated with the eruptions, they can also pose further threats: the chemical composition of the planetary atmospheres is probably altered by the eruptions on a regular basis, and the atmospheres can be also eroded in the long term. A sufficiently strong magnetic field of the exoplanets could protect their atmosphere from the harmful effects of such eruptions, but an Earth-like exoplanet would need a magnetic field in the order of 10–1000 Gauss to be shielded from such flares (as a comparison, the Earth's magnetic field is ≈0.5 Gauss).[8]

The study in 2020 have found super-flare (defined as flare releasing at least 1026 J - twice the Carrington event) rate of TRAPPIST-1 is 4.2+1.9

−0.2 year−1, insufficient to permanently deplete ozone in the atmosphere of habitable-zone planets. Also, flare UV emission of TRAPPIST-1 is grossly insufficient to compensate the lack of quiescent UV emission and to power prebiotic chemistry.[68]

Probability of interplanetary panspermia

Hypothetically, if the conditions of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system were to be able to support life, any possible life that had developed through abiogenesis on one of the planets would likely be spread to other planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system via panspermia, the transfer of life from one planet to another.[69] Due to the close proximity of the planets in the habitable zone with a separation of at least ~0.01 AU from each other, the probability of life being transferred from one planet to another is greatly enhanced.[70] Compared to the likelihood of panspermia from Earth to Mars, the likelihood of interplanetary panspermia in the TRAPPIST-1 system is thought to be about 10,000 times higher.[69]

Radio signal searches

In February 2017, Seth Shostak, senior astronomer for the SETI Institute, noted, "[T]he SETI Institute used its Allen Telescope Array [in 2016] to observe the environs of TRAPPIST-1, scanning through 10 billion radio channels in search of signals. No transmissions were detected."[22] Additional observations with the more sensitive Green Bank Telescope did not show evidence of transmissions.[71]

Other observations

Existence of undiscovered planets

One study using the CAPSCam astrometric camera concluded that the TRAPPIST-1 system has no planets with a mass at least 4.6 MJ with year-long orbits and no planets with a mass at least 1.6 MJ with five-year orbits. The authors of the study noted, however, that their findings left areas of the TRAPPIST-1 system, most notably the zone in which planets would have intermediate-period orbits, unanalyzed.[72]

Possibility of moons

Stephen R. Kane, writing in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, notes that TRAPPIST-1 planets are unlikely to have large moons.[73][74] The Earth's Moon has a radius 27% that of Earth, so its area (and its transit depth) is 7.4% that of Earth, which would likely have been noted in the transit study if present. Smaller moons of 200–300 km (120–190 mi) radius would likely not have been detected.

At a theoretical level, Kane found that moons around the inner TRAPPIST-1 planets would need to be extraordinarily dense to be even theoretically possible. This is based on a comparison of the Hill sphere, which marks the outer limit of a moon's possible orbit by defining the region of space in which a planet's gravity is stronger than the tidal force of its star, and the Roche limit, which represents the smallest distance at which a moon can orbit before the planet's tides exceed its own gravity and pull it apart. These constraints do not rule out the presence of ring systems (where particles are held together by chemical rather than gravitational forces). The mathematical derivation is as follows:

is the Hill radius of the planet, calculated from the planetary semi-major axis , the mass of the planet , and the mass of the star . Note that the mass of the TRAPPIST-1 star is approximately 30,000 M⊕ (see data table above); the remaining figures are provided in the table below.

is the Roche limit of the planet, calculated from the radius of the planet , and the density of the planet . The table below was calculated using , an approximation of Earth's moon.

| Planet | (Earth masses) |

(Earth radii) |

(Earth density) |

(AU) |

(milliAU) |

(milliAU) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRAPPIST-1b | 1.374 | 1.116 | 0.987 | 0.0115 | 0.285 | 0.137 | 2.080 |

| TRAPPIST-1c | 1.308 | 1.097 | 0.991 | 0.0158 | 0.386 | 0.134 | 2.880 |

| TRAPPIST-1d | 0.388 | 0.788 | 0.792 | 0.0223 | 0.363 | 0.090 | 4.034 |

| TRAPPIST-1e | 0.692 | 0.920 | 0.889 | 0.0293 | 0.578 | 0.109 | 5.303 |

| TRAPPIST-1f | 1.039 | 1.045 | 0.911 | 0.0385 | 0.870 | 0.125 | 6.960 |

| TRAPPIST-1g | 1.321 | 1.129 | 0.917 | 0.0468 | 1.146 | 0.135 | 8.489 |

| TRAPPIST-1h | 0.326 | 0.775 | 0.755 | 0.0619 | 0.951 | 0.087 | 10.931 |

Kane notes that moons near the edge of the Hill radius may be subject to resonant removal during planetary migration, leading to a Hill reduction (moon removal) factor roughly estimated as 1⁄3 for typical systems and 1⁄4 for the TRAPPIST-1 system; thus moons are not expected for planets b and c (whereby is less than four). Furthermore, tidal interactions with the planet can result in a transfer of energy from the planet's rotation to the moon's orbit, causing a moon to leave the stable region over time. For these reasons, even the outer TRAPPIST-1 planets are believed to be unlikely to have moons.

Gallery

Artist's concept of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system.

Artist's concept of the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system. The TRAPPIST-1 system compared to the Solar System; the orbits of its seven planets would easily fit inside the orbit of Mercury[22]

The TRAPPIST-1 system compared to the Solar System; the orbits of its seven planets would easily fit inside the orbit of Mercury[22]

See also

- HD 10180, a star with at least seven known planets

- Kepler-90, a star with eight known planets

- KIC 8462852, another star with notable transit data

- LHS 1140, another star with a planetary system suitable for atmospheric studies

- Active SETI, the attempt to transmit messages to intelligent extraterrestrial life

- Habitability of red dwarf systems

- List of potentially habitable exoplanets

- Nikole Lewis

Notes

- Based on photometric spectral type estimation.

- Taking the absolute visual magnitude of TRAPPIST-1 and the absolute visual magnitude of the Sun , the visual luminosity can be calculated by

- The surface gravity is calculated directly from Newton's law of universal gravitation, which gives the formula , where M is the mass of the object, r is its radius, and G is the gravitational constant. In this case, a log g of ≈5.227 indicates a surface gravity around 172 times stronger than Earth's.

References

- Cutri, R. M.; Skrutskie, M. F.; Van Dyk, S.; et al. (June 2003). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: 2MASS All-Sky Catalog of Point Sources (Cutri+ 2003)". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues (2246): II/246. Bibcode:2003yCat.2246....0C.

- Costa, E.; Mendez, R. A.; Jao, W.-C.; Henry, T. J.; Subasavage, J. P.; Ianna, P. A. (4 August 2006). "The Solar Neighborhood. XVI. Parallaxes from CTIOPI: Final Results from the 1.5 m Telescope Program". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (3): 1234. Bibcode:2006AJ....132.1234C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.622.2310. doi:10.1086/505706.

- Lienhard, F.; Queloz, D.; Gillon, M.; Burdanov, A.; Delrez, L.; Ducrot, E.; Handley, W.; Jehin, E.; Murray, C. A.; Triaud, A H M J.; Gillen, E.; Mortier, A.; Rackham, B. V. (2020), "Global Analysis of the TRAPPIST Ultra-Cool Dwarf Transit Survey", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 497 (3): 3790–3808, arXiv:2007.07278, Bibcode:2020MNRAS.497.3790L, doi:10.1093/mnras/staa2054, S2CID 220525769

- Van Grootel, Valerie; Fernandes, Catarina S.; Gillon, Michaël; et al. (January 2018). "Stellar parameters for TRAPPIST-1". The Astrophysical Journal. 853 (1). 30. arXiv:1712.01911. Bibcode:2018ApJ...853...30V. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aaa023. S2CID 54034373.

- Agol, Eric; Dorn, Caroline; Grimm, Simon L.; Turbet, Martin; Ducrot, Elsa; Delrez, Laetitia; Gillon, Michael; Demory, Brice-Olivier; Burdanov, Artem; Barkaoui, Khalid; Benkhaldoun, Zouhair; Bolmont, Emeline; Burgasser, Adam; Carey, Sean; Julien de Wit; Fabrycky, Daniel; Foreman-Mackey, Daniel; Haldemann, Jonas; Hernandez, David M.; Ingalls, James; Jehin, Emmanuel; Langford, Zachary; Leconte, Jeremy; Lederer, Susan M.; Luger, Rodrigo; Malhotra, Renu; Meadows, Victoria S.; Morris, Brett M.; Pozuelos, Francisco J.; et al. (2020), Refining the transit timing and photometric analysis of TRAPPIST-1: Masses, radii, densities, dynamics, and ephemerides, arXiv:2010.01074

- Viti, Serena; Jones, Hugh R. A. (November 1999). "Gravity dependence at the bottom of the main sequence". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 351: 1028–1035. Bibcode:1999A&A...351.1028V.

- Delrez, Laetitia; Gillon, Michael; H.M.J, Amaury; et al. (April 2018). "Early 2017 observations of TRAPPIST-1 with Spitzer". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 475 (3): 3577–3597. arXiv:1801.02554. Bibcode:2018MNRAS.475.3577D. doi:10.1093/mnras/sty051. S2CID 54649681.

- Vida, Krisztián; Kővári, Zsolt; Pál, András; et al. (June 2017). "Frequent Flaring in the TRAPPIST-1 System—Unsuited for Life?". The Astrophysical Journal. 841 (2). 124. arXiv:1703.10130. Bibcode:2017ApJ...841..124V. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa6f05. S2CID 118827117.

- Barnes, J. R.; Jenkins, J. S.; Jones, H. R. A.; et al. (April 2014). "Precision radial velocities of 15 M5-M9 dwarfs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 439 (3): 3094–3113. arXiv:1401.5350. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.439.3094B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu172. S2CID 16005221.

- Burgasser, Adam J.; Mamajek, Eric E. (September 2017). "On the Age of the TRAPPIST-1 System". The Astrophysical Journal. 845 (2). 110. arXiv:1706.02018. Bibcode:2017ApJ...845..110B. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa7fea. S2CID 119464994.

- "2MASS J23062928-0502285". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg.

- Gillon, M.; Jehin, E.; Lederer, S. M.; Delrez, L.; De Wit, J.; Burdanov, A.; Van Grootel, V.; Burgasser, A. J.; Triaud, A. H. M. J.; Opitom, C.; Demory, B.-O.; Sahu, D. K.; Bardalez Gagliuffi, D.; Magain, P.; Queloz, D. (2016). "Temperate Earth-sized planets transiting a nearby ultracool dwarf star" (PDF). Nature. 533 (7602): 221–224. arXiv:1605.07211. Bibcode:2016Natur.533..221G. doi:10.1038/nature17448. PMC 5321506. PMID 27135924.

- "Three Potentially Habitable Worlds Found Around Nearby Ultracool Dwarf Star – Currently the best place to search for life beyond the Solar System". European Southern Observatory. 2 May 2016.

- Chang, Kenneth (22 February 2017). "7 Earth-Size Planets Identified in Orbit Around a Dwarf Star". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- "Twinkle, Twinkle Little Trappist". The New York Times. 24 February 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Witze, A. (22 February 2017). "These seven alien worlds could help explain how planets form". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.21512. S2CID 132356961.

- Marchis, Franck (22 February 2017). "Wonderful potentially habitable worlds around TRAPPIST-1". The Planetary Society. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- Tamayo, Daniel; Rein, Hanno; Petrovich, Cristobal; Murray, Norman (10 May 2017). "Convergent Migration Renders TRAPPIST-1 Long-lived". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 840 (2). L19. arXiv:1704.02957. Bibcode:2017ApJ...840L..19T. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa70ea. S2CID 119336960.

- Chang, Kenneth (10 May 2017). "The Harmony That Keeps Trappist-1's 7 Earth-size Worlds From Colliding". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- Sample, Ian (2 May 2016). "Could these newly-discovered planets orbiting an ultracool dwarf host life?". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Bennett, Jay (2 May 2016). "Three New Planets Are the Best Bets for Life". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Shostak, Seth (22 February 2017). "This Weird Planetary System Seems Like Something From Science Fiction". NBC News. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "TRAPPIST-1 Planet Lineup". NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 22 February 2017.

- Gillon, Michaël; Triaud, Amaury; Jehin, Emmanuël; et al. (22 February 2017). "Ultracool Dwarf and the Seven Planets". European Southern Observatory. eso1706. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Landau, Elizabeth; Chou, Felicia; Potter, Sean (21 February 2017). "NASA telescope reveals largest batch of Earth-size, habitable-zone planets around single star". Exoplanet Exploration. NASA. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- Bolmont, E.; Selsis, F.; Owen, J. E.; Ribas, I.; Raymond, S. N.; Leconte, J.; Gillon, M. (2017). "Water loss from terrestrial planets orbiting ultracool dwarfs: implications for the planets of TRAPPIST-1". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 464 (3): 3728–3741. arXiv:1605.00616. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.464.3728B. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw2578. S2CID 53687987.

- Kelley, Peter (20 November 2018). "Study brings new climate models of small star TRAPPIST 1's seven intriguing worlds". UW News. University of Washington. Retrieved 23 February 2019.

- Bryant, Tracey (22 February 2017). "Celestial Connection". University of Delaware.

- Gizis, John E.; Monet, David G.; Reid, I. Neill; Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Liebert, James; Williams, Rik J. (2000). "New Neighbors from 2MASS: Activity and Kinematics at the Bottom of the Main Sequence". The Astronomical Journal. 120 (2): 1085–1095. arXiv:astro-ph/0004361. Bibcode:2000AJ....120.1085G. doi:10.1086/301456. S2CID 18819321.

- Gramer, Robbie (22 February 2017). "News So Foreign It's Out of This World: Scientists Discover Seven New Potentially Habitable Planets". Foreign Policy.

Scientists named the system TRAPPIST-1 after the telescope that first found the system. (For all those Belgian beer lovers out there, the telescope’s name is an homage to the trappist religious orders in Belgium, known for brewing some of the world’s best beers.)

- Jehin, Emmanuël; Queloz, Didier; Boffin, Henri; et al. (8 June 2010). "New National Telescope at La Silla". European Southern Observatory. eso1023. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Hessman, F. V.; Dhillon, V. S.; Winget, D. E.; et al. (3 December 2010). "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets". arXiv:1012.0707 [astro-ph.SR].

- Koberlein, Brian (22 February 2017). "Here's How Astronomers Found Seven Earth-Sized Planets Around A Dwarf Star". Forbes. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Reiners, A.; Basri, G. (2010). "A Volume-Limited Sample of 63 M7-M9.5 Dwarfs. II. Activity, Magnetism, and the Fade of the Rotation-Dominated Dynamo". The Astrophysical Journal. 710 (2): 924–935. arXiv:0912.4259. Bibcode:2010ApJ...710..924R. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/710/2/924. S2CID 119265900.

- Cain, Fraser (23 December 2015). "Temperature of the Sun". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Williams, Matt (24 September 2016). "What is the Life Cycle of the Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- Luger, Rodrigo; Sestovic, Marko; Kruse, Ethan; Grimm, Simon L.; Demory, Brice-Oliver; et al. (12 March 2017). "A terrestrial-sized exoplanet at the snow line of TRAPPIST-1". Nature Astronomy. 1 (6): 0129. arXiv:1703.04166. Bibcode:2017NatAs...1E.129L. doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0129. S2CID 54770728.

- Howell, S.; Everett, M.; Horch, E. (September 2016). "Speckle Imaging Excludes Low-mass Companions Orbiting the Exoplanet Host Star TRAPPIST-1". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 829 (1): 2–9. arXiv:1610.05269. Bibcode:2016ApJ...829L...2H. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/829/1/L2. S2CID 119183657.

- Adams, Fred C.; Laughlin, Gregory; Graves, Genevieve J. M. (December 2004). "Red Dwarfs and the End of the Main Sequence". Gravitational Collapse: From Massive Stars to Planets. Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica (Serie de Conferencias). 22. pp. 46–49. Bibcode:2004RMxAC..22...46A. ISBN 978-970-32-1160-9.

- Gillon, M.; Triaud, A. H. M. J.; Demory, B.-O.; et al. (February 2017). "Seven temperate terrestrial planets around the nearby ultracool dwarf star TRAPPIST-1" (PDF). Nature. 542 (7642): 456–460. arXiv:1703.01424. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..456G. doi:10.1038/nature21360. PMC 5330437. PMID 28230125.

- Chou, Felicia; Potter, Sean; Landau, Elizabeth (22 February 2017). "NASA Telescope Reveals Largest Batch of Earth-Size, Habitable-Zone Planets Around Single Star". NASA. Release 17-015.

- Wall, Mike (22 February 2017). "Major Discovery! 7 Earth-Size Alien Planets Circle Nearby Star". Space.com.

- Redd, Nola Taylor (24 February 2017). "TRAPPIST-1: System with 7 Earth-Size Exoplanets". Space.com.

- Snellen, Ignas A. G. (23 February 2017). "Astronomy: Earth's seven sisters". Nature. 542 (7642): 421–423. Bibcode:2017Natur.542..421S. doi:10.1038/542421a. hdl:1887/75076. PMID 28230129.

- Howell, Steve B.; Everett, Mark E.; Horch, Elliott P.; et al. (September 2016). "Speckle Imaging Excludes Low-mass Companions Orbiting the Exoplanet Host Star TRAPPIST-1". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 829 (1). L2. arXiv:1610.05269. Bibcode:2016ApJ...829L...2H. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/829/1/L2. S2CID 119183657.

- Bourrier, Vincent; de Wit, Julien; Jäger, Mathias (31 August 2017). "Hubble delivers first hints of possible water content of TRAPPIST-1 planets". SpaceTelescope.org. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- "First evidence of water found on TRAPPIST-1 planets". The Indian Express. Press Trust of India. 4 September 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- "TRAPPIST-1 Planets Probably Rich in Water – First glimpse of what Earth-sized exoplanets are made of". www.eso.org. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Grimm, Simon L.; Demory, Brice-Olivier; Gillon, Michaël; et al. (21 January 2018). "The nature of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 613: A68. arXiv:1802.01377. Bibcode:2018A&A...613A..68G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201732233. S2CID 3441829.

- de Wit, Julien; Wakeford, Hannah R.; Lewis, Nikole K.; et al. (March 2018). "Atmospheric reconnaissance of the habitable-zone Earth-sized planets orbiting TRAPPIST-1". Nature Astronomy. 2 (3): 214–219. arXiv:1802.02250. Bibcode:2018NatAs...2..214D. doi:10.1038/s41550-017-0374-z. S2CID 119085332.

- Hirano, Teruyuki; Gaidos, Eric; Winn, Joshua N.; Dai, Fei; Fukui, Akihiko; Kuzuhara, Masayuki; Kotani, Takayuki; Tamura, Motohide; Hjorth, Maria; Albrecht, Simon; Huber, Daniel; Bolmont, Emeline; Harakawa, Hiroki; Hodapp, Klaus; Ishizuka, Masato; Jacobson, Shane; Konishi, Mihoko; Kudo, Tomoyuki; Kurokawa, Takashi; Nishikawa, Jun; Omiya, Masashi; Serizawa, Takuma; Ueda, Akitoshi; Weiss, Lauren M. (2020). "Evidence for Spin-orbit Alignment in the TRAPPIST-1 System". The Astrophysical Journal. 890 (2): L27. arXiv:2002.05892. Bibcode:2020ApJ...890L..27H. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab74dc. S2CID 211126651.

- Russo, Matt, What does the universe sound like? A musical tour, retrieved 24 October 2019

- Ormel, Chris; Liu, Beibei; Schoonenberg, Djoeke (20 March 2017). "Formation of TRAPPIST-1 and other compact systems". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 604 (1): A1. arXiv:1703.06924. Bibcode:2017A&A...604A...1O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201730826. S2CID 4606360.

- Schoonenberg, Djoeke; Liu, Beibei; Ormel, Chris W.; Dorn, Caroline (2019). "A pebble-driven formation model for compact planetary systems like TRAPPIST-1". Astronomy & Astrophysics. A149: 627. arXiv:1906.00669. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201935607. S2CID 189928229.

- Vinson, Alec; Tamayo, Daniel; Hansen, Brad (2019). "The Chaotic Nature of TRAPPIST-1 Planetary Spin States". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 488 (4): 5739–5747. arXiv:1905.11419. Bibcode:2019MNRAS.488.5739V. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz2113. S2CID 167217467.

- Barr, Amy C.; et al. (May 2018). "Interior Structures and Tidal Heating in the TRAPPIST-1 Planets". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 613. A37. arXiv:1712.05641. Bibcode:2018A&A...613A..37B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201731992. S2CID 119516532.

- Wheatley, Peter J.; Louden, Tom; Bourrier, Vincent; Ehrenreich, David; Gillon, Michaël (February 2017). "Strong XUV irradiation of the Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting the ultracool dwarf TRAPPIST-1". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 465 (1): L74–L78. arXiv:1605.01564. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.465L..74W. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slw192. S2CID 30087787.

- O'Malley-James, J. T.; Kaltenegger, L. (28 March 2017). "UV Surface Habitability of the TRAPPIST-1 System". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 469 (1): L26–L30. arXiv:1702.06936. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.469L..26O. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slx047. S2CID 119456262.

- "Artist's view of planets transiting red dwarf star in TRAPPIST-1 system". SpaceTelescope.org. 20 July 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Kaplan, Sarah (22 February 2017). "Here's what you should know about the newfound TRAPPIST-1 solar system". The Washington Post.

- Gleiser, M. (23 February 2017). "Trappist-1 Planet Discovery Ignites Enthusiasm in Search For Alien Life". NPR. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- de Wit, Julien; Wakeford, Hannah R.; Gillon, Michaël; et al. (1 September 2016). "A combined transmission spectrum of the Earth-sized exoplanets TRAPPIST-1 b and c". Nature. 537 (7618): 69–72. arXiv:1606.01103. Bibcode:2016Natur.537...69D. doi:10.1038/nature18641. PMID 27437572. S2CID 205249853.

- Bourrier, V.; Ehrenreich, D.; Wheatley, P. J.; et al. (February 2017). "Reconnaissance of the TRAPPIST-1 exoplanet system in the Lyman-α line". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 599 (3). L3. arXiv:1702.07004. Bibcode:2017A&A...599L...3B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201630238. S2CID 55149926.

- Swain, M. (2008). "Probing the Atmospheres of Exoplanets" (PDF). Hubble 2008: Science Year in Review. NASA. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- Osgood, M. (22 February 2017). "Sagan Institute director explains what life could be like near Trappist-1". Cornell University. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- Barstow, J. K.; Irwin, P. G. J. (September 2016). "Habitable worlds with JWST: Transit spectroscopy of the TRAPPIST-1 system?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 461 (1): L92–L96. arXiv:1605.07352. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.461L..92B. doi:10.1093/mnrasl/slw109. S2CID 17058804.

- Gillon, Michaël; Meadows, Victoria; Agol, Eric; Burgasser, Adam J.; Deming, Drake; Doyon, René; Fortney, Jonathan; Kreidberg, Laura; Owen, James; Selsis, Franck; Julien de Wit; Lustig-Yaeger, Jacob; Rackham, Benjamin V. (2020). "The TRAPPIST-1 JWST Community Initiative". arXiv:2002.04798 [astro-ph.EP].

- Glazier, Amy L.; Howard, Ward S.; Corbett, Hank; Law, Nicholas M.; Ratzloff, Jeffrey K.; Fors, Octavi; Daniel del Ser (2020), "Evryscope and K2 Constraints on TRAPPIST-1 Superflare Occurrence and Planetary Habitability", The Astrophysical Journal, 900 (1): 27, arXiv:2006.14712, Bibcode:2020ApJ...900...27G, doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aba4a6, S2CID 220128346

- Wall, Mike (23 June 2017). "Enhanced interplanetary panspermia in the TRAPPIST-1 system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (26): 6689–6693. arXiv:1703.00878. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.6689L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1703517114. PMC 5495259. PMID 28611223.

- Lingam, Manasvi; Loeb, Abraham (15 March 2017). "Enhanced interplanetary panspermia in the TRAPPIST-1 system". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (26): 6689–6693. arXiv:1703.00878. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.6689L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1703517114. PMC 5495259. PMID 28611223.

- Pinchuk, Pavlo; Margot, Jean-Luc; Greenberg, Adam H.; Ayalde, Thomas; Bloxham, Chad; Boddu, Arjun; Chinchilla-Garcia, Luis Gerardo; Cliffe, Micah; Gallagher, Sara; Hart, Kira; Hesford, Brayden; Mizrahi, Inbal; Pike, Ruth; Rodger, Dominic; Sayki, Bade; Schneck, Una; Tan, Aysen; Xiao, Yinxue “Yolanda”; Lynch, Ryan S. (2019). "A Search for Technosignatures from TRAPPIST-1, LHS 1140, and 10 Planetary Systems in the Kepler Field with the Green Bank Telescope at 1.15–1.73 GHz". The Astronomical Journal. 157 (3): 122. arXiv:1901.04057. Bibcode:2019AJ....157..122P. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ab0105. ISSN 1538-3881. S2CID 113397518.

- Boss, Alan; Weinberger, Alycia; Keiser, Sandra; Astraatmadja, Tri; Anglada-Escude, Guillem; Thompson, Ian (2017). "Astrometric Constraints on the Masses of Long-Period Gas Giant Planets in the TRAPPIST-1 Planetary System". The Astronomical Journal. 154 (3). 103. arXiv:1708.02200. Bibcode:2017AJ....154..103B. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa84b5. S2CID 118912154.

- Howell, Elizabeth (5 May 2017). "TRAPPIST-1 Planets Have No Large Moons, Raising Questions about Habitability". Seeker. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- Kane, Stephen R. (April 2017). "Worlds without Moons: Exomoon Constraints for Compact Planetary Systems". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 839 (2). L19. arXiv:1704.01688. Bibcode:2017ApJ...839L..19K. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/aa6bf2. S2CID 119380874.

Further reading

- Levenson, Thomas (2 May 2016). "Astronomers Have Found Planets in the Habitable Zone of a Nearby Star". The Atlantic. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to TRAPPIST-1. |

- TRAPPIST.one, the discovery team's official website

- "NASA's Spitzer Reveals Largest Batch of Earth-Size, Habitable-Zone Planets Around a Single Star" on YouTube by NASA

- "NASA & TRAPPIST-1: A Treasure Trove of Planets Found" on YouTube by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- ESOcast 83: "Ultracool Dwarf with Planets" by the European Southern Observatory

- Interactive visualisation of the TRAPPIST-1 System