Taylor County, Wisconsin

Taylor County is a county in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2010 census, the population was 20,689.[1] Its county seat is Medford.[2]

Taylor County | |

|---|---|

The Taylor County courthouse in Medford is on the National Register of Historic Places. | |

Location within the U.S. state of Wisconsin | |

Wisconsin's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 45°13′N 90°30′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1875 |

| Seat | Medford |

| Largest city | Medford |

| Area | |

| • Total | 984 sq mi (2,550 km2) |

| • Land | 975 sq mi (2,530 km2) |

| • Water | 9.5 sq mi (25 km2) 1.0%% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 20,689 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 20,343 |

| • Density | 21/sq mi (8.1/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 7th |

| Website | www |

History

The earliest recorded event in Taylor county probably occurred in 1661, when Wisconsin was part of New France. A band of Huron Indians from eastern Ontario had fled the Iroquois and taken refuge near the headwaters of the Black River, probably around Lake Chelsea in the northeast part of the county. Father René Menard, a French Jesuit priest who had travelled up the Great Lakes as far as Keweenaw Bay in upper Michigan, heard that these Hurons were starving. He decided to try to reach them to baptize them, despite his own weak health and scant supplies. In mid-summer he and a French fur trader set out, following rivers and streams in birchbark canoes down into Wisconsin. Finally, a day's journey from the Huron camp, Father Menard separated from his travelling companion at a rapids to carry some supplies. He was never seen again. The place where he disappeared is believed to be the dells of the Big Rib River, below Goodrich in the southeast corner of Taylor county.[3]

On June 8, 1847, before any settlers or loggers, a team of surveyors entered the county[4] southwest of Medford, where County E now enters from Clark County. They were working for the U.S. government, marking a north–south line called the Fourth Principal Meridian, from which much of the land in the state would be measured. For six days they worked their way through woods and swamps, up what is now the southern part of E and across the valley that is now the Mondeaux Flowage, before continuing north into what is now Price County. The head of the team wrote of the trip:

During four consecutive weeks there was not a dry garment in the party, day or night... we were constantly surrounded and as constantly excoriated by swarms or rather clouds of mosquitoes, and still more troublesome insects...[5]

On their way through the county, they and other surveyors recorded a forest then dominated by hemlock, yellow birch and sugar maple, with white pine the fourth or sixth most frequent. The mix of tree species then resembled today's Gerstberger Pines grove southeast of Rib Lake.[6]

Logging began in the late 1850s. Loggers came from Cortland County, New York, Carroll County, New Hampshire, Orange County, Vermont and Down East Maine in what is now Washington County, Maine and Hancock County, Maine. These were "Yankee" migrants, that is to say they were descended from the English Puritans who had settled New England during the 1600s. As a result of this heritage many of the towns in Taylor County are named after towns in New England such as Chelsea which is named after Chelsea, Vermont and Westboro which is named after Westborough, Massachusetts.[7] Medford was named after Medford, Massachusetts.[8] Loggers came up the rivers and floated pine logs out in spring and early summer log drives, down the Big Rib River into the Wisconsin River, down the Black River to the south, and west down the Jump and the Yellow River into the Chippewa.[9]

In 1872 and 73 the Wisconsin Central Railroad built its line up through Stetsonville, Medford, Whittlesey, Chelsea, and Westboro, with a spur to Rib Lake, on its way to Ashland. To finance building this line, the U.S. Government gave the railroad half the land, the odd-numbered sections, of a good share of the county.[10] The railroad began to haul out the trees that didn't float well. Most early settlement was along this railroad, with few settlers in the west or east ends of the county even by the 1890s.[11]

In 1875 Taylor County with its current boundaries was carved out of the larger Chippewa, Lincoln and Clark counties and a bit of Marathon, with the county seat at Medford. The county was probably named for Wisconsin's governor at the time, William Robert Taylor. At the time virtually all of Taylor County's inhabitants were Yankee migrants from New England, which influenced the naming of the county, as William Robert Taylor was from Connecticut of English descent.[12][13] It was initially divided into four towns—Westboro, Chelsea, Medford and Little Black[14]—each stretching the width of the county.[15]

From around 1902 to 1905 the Stanley, Merrill and Phillips Railway ran a line up the west end of the county through Polley, Gilman, Hannibal and Jump River. In 1902 the Eau Claire, Chippewa Falls, and Northeastern Railroad (better known as Omaha) pushed in from Holcombe through Hannibal to now-abandoned Hughey on the Yellow River. In 1905 the Wisconsin Central Railroad built its line through Clark (now a ghost town), Lublin, Polley, Gilman and Donald, heading for Superior. The SM&P and Omaha were primarily logging railroads, which hauled out lumber and incidentally transported passengers and other cargo. With the lumber gone, the SM&P shut down in 1933.[16]

After the good timber was gone, the lumber companies sold many of the cutover forties to farm families. Initially they tried making their living in various ways: selling milk, eggs, beef and wool, growing cucumbers and peas, and various other schemes. But before long dairy had become the predominant form of agriculture in the county. By 1923 Medford had the second largest co-op creamery in Wisconsin. The number of dairy farms peaked around 3,300 in the early 1940s and had dropped to 1,090 by 1995.[17]

Much of the cut-over north-central part of the county was designated part of the Chequamegon National Forest in 1933.[18] Mondeaux Dam Recreation Area and other parts of the forest were developed by the Civilian Conservation Corps starting in 1933. CCC camps were at Mondeaux, Perkinstown, and near the current Jump River fire tower. Today hikers can follow the Ice Age National Scenic Trail through the national forest and the northeast corner of the county.

The major early industry was the production of sawlogs, lumber, and shingles.[19] Large sawmills were at Medford and Rib Lake. Medford, Perkinstown and Rib Lake had tanneries, which used local hemlock bark in the tanning process. Whittlesey had an early brickyard.[11] Industry has diversified since, into creameries, window manufacturers, plastics, and food processing - mostly at Medford.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 984 square miles (2,550 km2), of which 975 square miles (2,530 km2) is land and 9.5 square miles (25 km2) (1.0%) is water.[21]

Taylor county's terrain was shaped chiefly by glaciers. Geologists believe that 15,000 to 25,000 years ago the Laurentide Ice Sheet pushed down from Canada across what are now the Great Lakes, and over much of the northern U.S. One of the ice sheet's lobes bulldozed down over two thirds of Taylor county, at its farthest extent covering a line from Westboro through Perkinstown to Lublin. The ice sheet pushed down that far, then melted back, leaving the band of choppy hills and little lakes that cuts diagonally across the county. This band of hills is called the Perkinstown terminal moraine. North and west of the moraine, in the corner of the county toward Jump River, that last glacier left behind a more gently rolling plain of glacial till.

The striking glacial features in this area are glacial erratic boulders and eskers. Along with the Mondeaux and Lost Lake eskers, there are others in the towns of Westboro, Pershing, Aurora and Taft. The southeast corner of the county toward Stetsonville and Goodrich was not covered by the last glacier, but was covered by earlier ones. Here too they left glacial till, but the land is generally flatter and less rocky since erosion has had more time to level things.[20]

Beneath the glacial till lies Cambrian and Precambrian bedrock. Outcrops have been exposed in places by the Jump and Yellow Rivers.[17][20] An unmined copper and gold deposit known as "the Bend Project" lies north of Perkinstown,[22][23] which geologists believe was formed up to two billion years ago by a black smoker, a volcanic vent under an ancient ocean.[24]

The county straddles a divide between three river systems. The Jump River and Yellow flow west into the Chippewa river valley. The Big Rib River flows southeast to the Wisconsin. And the Black River flows out to the south. All eventually feed the Mississippi.

Adjacent counties

- Price County - north

- Lincoln County - east

- Marathon County - southeast

- Clark County - south

- Chippewa County - west

- Rusk County - northwest

National protected area

- Chequamegon National Forest (part)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 2,311 | — | |

| 1890 | 6,731 | 191.3% | |

| 1900 | 11,262 | 67.3% | |

| 1910 | 13,641 | 21.1% | |

| 1920 | 18,045 | 32.3% | |

| 1930 | 17,685 | −2.0% | |

| 1940 | 20,105 | 13.7% | |

| 1950 | 18,456 | −8.2% | |

| 1960 | 17,843 | −3.3% | |

| 1970 | 16,958 | −5.0% | |

| 1980 | 18,817 | 11.0% | |

| 1990 | 18,901 | 0.4% | |

| 2000 | 19,680 | 4.1% | |

| 2010 | 20,689 | 5.1% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 20,343 | [25] | −1.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] 1790–1960[27] 1900–1990[28] 1990–2000[29] 2010–2019[1] | |||

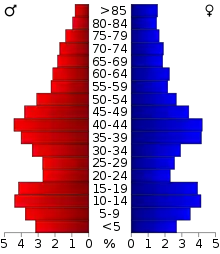

As of the census[30] of 2000, there were 19,680 people, 7,529 households, and 5,345 families residing in the county. The population density was 20 people per square mile (8/km2). There were 8,595 housing units at an average density of 9 per square mile (3/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 98.71% White, 0.09% Black or African American, 0.19% Native American, 0.23% Asian, 0.19% from other races, and 0.59% from two or more races. 0.65% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 57.9% were of German, 9.1% Polish, 5.3% American and 5.3% Norwegian ancestry. 96.2% spoke English, 1.7% German and 1.2% Spanish as their first language.

There were 7,529 households, out of which 33.80% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.30% were married couples living together, 7.10% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.00% were non-families. 24.70% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.20% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.58 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 27.10% under the age of 18, 7.60% from 18 to 24, 28.30% from 25 to 44, 21.80% from 45 to 64, and 15.20% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 102.60 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.40 males.

In 2017, there were 202 births, giving a general fertility rate of 64.0 births per 1000 women aged 15–44, the 33rd highest rate out of all 72 Wisconsin counties.[31] Additionally, there were fewer than five reported induced abortions performed on women of Taylor County residence in 2017.[32]

Transportation

The state of Wisconsin has jurisdiction over 120 miles (190 km) of state highways in Taylor County, including STH-13, STH-64, STH-73, STH-97, and STH-102. STH-13 runs north–south through the eastern half of the county and STH-73 is the major north–south highway in the western half of the county. STH-64 is the major highway running east–west through Taylor county. Through a contractual agreement with the state, the Taylor County Highway Department is responsible for maintenance of state highways and right-of-ways.

A network of 250 miles (400 km) of county highways serves Taylor County's rural areas. Major east–west highways include CTH-A, CTH-D, CTH-M, and CTH-O. Major north–south routes include CTH-C, CTH-E, and CTH-H.

Towns in Taylor County are responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of their individual town roads.

The county has one designated Rustic Road, Rustic Road 1 located in the Town of Rib Lake. Dedicated in 1975, this 5-mile-long (8.0 km) gravel road between STH-102 and CTH-D near Rib Lake was the first Rustic Road in Wisconsin. It winds over wooded hills and valleys created by glaciers nearly 12,000 years ago. A historical marker alongside the road (at Hwy 102 and RR1) commemorates the designation.[33]

Major highways

Highway 13 (Wisconsin)

Highway 13 (Wisconsin) Highway 64 (Wisconsin)

Highway 64 (Wisconsin) Highway 73 (Wisconsin)

Highway 73 (Wisconsin) Highway 97 (Wisconsin)

Highway 97 (Wisconsin) Highway 102 (Wisconsin)

Highway 102 (Wisconsin)

Airports

- KMDZ - Taylor County

The primary airport in the county is the Taylor County Airport (KMDZ). There are six other private landing strips in the county. Located approximately three miles southeast of Medford, the Taylor County Airport is the only public airport. The airport handles approximately 7,000 operations per year, with roughly 93% general aviation and 7% air taxi. The airport has a 6,000 foot asphalt runway with approved GPS approaches (Runway 9-27) and a 4,435 foot asphalt crosswind runway, also with GPS approaches, (Runway 16-34).[34] Services provided include: Jet A fuel, 100 low-lead AV gas, 24-hour fuel service, car rental, taxi service, large ramp/tie down area, flight instruction, and computerized weather briefing/flight planning service. An automated weather observation system (AWOS) is in place.

| Location | Airport name | Status | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roosevelt | Baldez Field | Private | T .30N-R.3W Sec.2 |

| Goodrich | Charlie's Field | Private | T.31N-R.3E Sec. 19 |

| Aurora | East Gilman Field | Private | T.31N-R.3W Sec. 18 |

| Browning | Lee's Flight Park | Private | T.31N-R.2E Sec 2 |

| Medford | Memorial Hospital of Taylor Co. Heliport | Private | T.31N-R.1E Sec. 28 |

| Little Black | Taylor County Airport | Public | T.30N-R.2E Sec. 7 |

| Goodrich | John's Field | Private | T.31N-R.3E Sec. 24 |

Communities

City

- Medford (county seat)

Villages

Towns

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

Population

Taylor County experienced a population decrease between 1950 and 1970, but since 1970 the county has gained 2,722 people.

| Area | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | Numeric Change 1950-2000 | Jan 1, 2006 Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. Aurora | 564 | 563 | 466 | 461 | 473 | 386 | -178 | 375 |

| T. Browning | 630 | 630 | 644 | 702 | 740 | 850 | 220 | 889 |

| T. Chelsea | 603 | 566 | 554 | 677 | 731 | 719 | 116 | 754 |

| T. Cleveland | 458 | 358 | 250 | 286 | 235 | 262 | -196 | 272 |

| T. Deer Creek | 780 | 810 | 764 | 747 | 738 | 733 | -47 | 750 |

| T. Ford | 334 | 306 | 248 | 274 | 254 | 276 | -58 | 271 |

| T. Goodrich | 460 | 414 | 373 | 408 | 454 | 487 | 27 | 497 |

| T. Greenwood | 758 | 653 | 635 | 705 | 634 | 642 | -116 | 672 |

| T. Grover | 266 | 232 | 210 | 229 | 214 | 233 | -33 | 239 |

| T. Hammel | 516 | 526 | 509 | 562 | 633 | 735 | 219 | 749 |

| T. Holway | 834 | 859 | 837 | 903 | 779 | 854 | 20 | 879 |

| T. Jump River | 448 | 391 | 355 | 365 | 330 | 311 | -137 | 317 |

| T. Little Black | 1216 | 1182 | 1133 | 1169 | 1195 | 1148 | -68 | 1187 |

| T. McKinley | 570 | 491 | 461 | 416 | 403 | 418 | -152 | 440 |

| T. Maplehurst | 462 | 405 | 348 | 345 | 300 | 359 | -103 | 364 |

| T. Medford | 1661 | 1622 | 1546 | 1834 | 1962 | 2216 | 555 | 2253 |

| T. Molitor | 200 | 168 | 199 | 212 | 183 | 263 | 63 | 269 |

| T. Pershing | 418 | 358 | 295 | 276 | 217 | 180 | -238 | 181 |

| T. Rib Lake | 769 | 657 | 615 | 682 | 746 | 768 | -1 | 775 |

| T.Roosevelt | 678 | 602 | 518 | 491 | 429 | 444 | -234 | 446 |

| T. Taft | 499 | 418 | 355 | 347 | 367 | 361 | -138 | 380 |

| T. Westboro | 783 | 720 | 631 | 706 | 663 | 660 | -123 | 699 |

| V. Gilman | 402 | 379 | 328 | 436 | 412 | 474 | 72 | 460 |

| V. Lublin | 161 | 160 | 143 | 142 | 129 | 110 | -51 | 100 |

| V. Rib Lake | 853 | 794 | 782 | 945 | 887 | 878 | 25 | 878 |

| V. Stetsonville | 334 | 319 | 305 | 487 | 511 | 563 | 229 | 563 |

| C. Medford | 2799 | 3260 | 3454 | 4010 | 4282 | 4350 | 1551 | 4260 |

| Taylor County | 18456 | 17843 | 16958 | 18817 | 18901 | 19680 | 1224 | 19917 |

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 71.7% 7,656 | 25.2% 2,693 | 3.2% 336 |

| 2016 | 69.5% 6,579 | 25.3% 2,393 | 5.3% 499 |

| 2012 | 58.9% 5,601 | 39.6% 3,763 | 1.6% 148 |

| 2008 | 49.1% 4,586 | 48.8% 4,563 | 2.1% 197 |

| 2004 | 58.5% 5,582 | 40.1% 3,829 | 1.4% 132 |

| 2000 | 58.7% 5,278 | 36.2% 3,254 | 5.1% 460 |

| 1996 | 39.2% 3,108 | 41.0% 3,253 | 19.8% 1,571 |

| 1992 | 36.5% 3,415 | 35.3% 3,305 | 28.2% 2,639 |

| 1988 | 52.5% 4,254 | 46.7% 3,785 | 0.8% 61 |

| 1984 | 59.5% 4,918 | 39.6% 3,271 | 1.0% 80 |

| 1980 | 51.3% 4,596 | 41.7% 3,739 | 7.0% 623 |

| 1976 | 45.5% 3,591 | 51.9% 4,101 | 2.7% 209 |

| 1972 | 55.9% 4,125 | 39.7% 2,934 | 4.4% 324 |

| 1968 | 44.0% 3,043 | 42.0% 2,910 | 14.0% 969 |

| 1964 | 32.8% 2,261 | 67.0% 4,624 | 0.2% 13 |

| 1960 | 47.6% 3,447 | 52.1% 3,768 | 0.3% 22 |

| 1956 | 57.8% 3,843 | 41.5% 2,759 | 0.8% 52 |

| 1952 | 63.5% 4,892 | 35.9% 2,768 | 0.7% 50 |

| 1948 | 42.1% 2,579 | 52.0% 3,184 | 5.9% 361 |

| 1944 | 48.2% 3,194 | 48.6% 3,215 | 3.2% 212 |

| 1940 | 47.8% 3,668 | 49.1% 3,771 | 3.1% 239 |

| 1936 | 25.2% 1,758 | 67.6% 4,721 | 7.3% 510 |

| 1932 | 18.6% 1,107 | 70.9% 4,219 | 10.4% 621 |

| 1928 | 54.6% 2,648 | 43.2% 2,095 | 2.2% 106 |

| 1924 | 29.5% 1,389 | 3.9% 185 | 66.6% 3,136 |

| 1920 | 72.7% 2,707 | 7.6% 282 | 19.7% 735 |

| 1916 | 60.2% 1,544 | 33.0% 845 | 6.8% 175 |

| 1912 | 33.8% 773 | 35.9% 821 | 30.3% 692 |

| 1908 | 60.8% 1,627 | 34.5% 924 | 4.7% 125 |

| 1904 | 67.8% 1,725 | 28.6% 728 | 3.6% 91 |

| 1900 | 57.5% 1,420 | 41.0% 1,012 | 1.5% 37 |

| 1896 | 64.5% 1,387 | 33.0% 710 | 2.5% 53 |

| 1892 | 43.2% 734 | 53.2% 904 | 3.6% 61 |

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 25, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Schmirler, A. A. A., "Wisconsin's Lost Missionary: The Mystery of Father Rene Menard", The Wisconsin Magazine of History, Volume 45, number 2, winter, 1961-1962.

- "Field Notes for T30N R1W". Original Field Notes and Plat Maps, 1833-1866. Board of Commissioners of Public Lands. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Kassulke, Natasha; David Mladneoff (August 2009). "See Wisconsin through the Eyes of 19th Century Surveyors" (PDF). Wisconsin Natural Resources Magazine. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2011.

- Finley, Robert W.,"Finley's Presettlement Vegetation" Archived 2013-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, 1976, University of Wisconsin.

- History of Taylor County, Wisconsin, Gilman, Wis. publisher not identified, 1923

- Wisconsin Encyclopedia By Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration, Jennifer L. Herman page 402

- Ruesch, Gordon (2011). Stephen Lars Kalmon (ed.). Our Home - Taylor County Wisconsin - A Topical History of our Roots. Taylor County History Project.

- Martin, Roy L. (January 1941). History of the Wisconsin Central (Bulletin No. 54). Boston, Mass.: The Railroad and Locomotive Historical Society, Inc., Baker Library, Harvard Business School. pp. 6, 18–21, 29.

- "Map of Taylor County and Part of Lincoln County, Wis, Showing Wisconsin Central RR Lands - Corrected to March 1, 1896". The Milwaukee Litho & Engr Co. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- "Dictionary of Wisconsin History", Wisconsin Historical Society.

- "Winnebago Took Its Name from an Indian Tribe". The Post-Crescent. December 28, 1963. p. 14. Retrieved August 25, 2014 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ruesch, H. O. (2011). Stephen Lars Kalmon (ed.). Our Home - Taylor County Wisconsin - A Topical History of our Roots. Taylor County History Project.

- Dahl, Ole Rasmussen (1880). Map of Chippewa, Price & Taylor Counties and the northern part of Clark County. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: The Milwaukee Litho & Engr Co.

- Nagel, Paul; (1979) S. M. & P. RY. The Stanley, Merrill and Phillips Railway

- Boelter, Joseph M.; Stacy S. Eichner; Angela M. Elg; William D. Fiala; Richard M. Johannes (July 2005). "Soil Survey of Taylor County, Wisconsin" (PDF). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, and Forest Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-04-15.

- "Nicolet National Forest". www.stateparks.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- "1876 Account of Taylor County" Archived January 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Wisconsin Land Commission.

- Attig, John W. (1993). "Pleistocene Geology of Taylor County, Wisconsin". Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey. Bulletin 90. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- "Potential Metallic Mining Development in Northern Wisconsin" (PDF). Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. April 1997. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- "Three-Dimensional Study of Geo-Chemical Dispersion at the Bend Project". US Geological Service. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- Berglund, Mark (December 7, 2011). "Up around the Bend". The Star News.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- "Annual Wisconsin Birth and Infant Mortality Report, 2017 P-01161-19 (June 2019): Detailed Tables". Archived from the original on June 19, 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- Reported Induced Abortions in Wisconsin, Office of Health Informatics, Division of Public Health, Wisconsin Department of Health Services. Section: Trend Information, 2013-2017, Table 18, pages 17-18

- "Rustic Road 1". Rustic Roads. Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved 2014-10-02.

- "KMDZ: Taylor County Airport". www.airnav.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- "Parishes in Wisconsin". The Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved September 8, 2012.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

External links

- Reminiscences and Anecdotes of early Taylor County, Arthur J. Latton's early history, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Taylor County official website

- Tannery, Dr. Loretta Kuse's page on early tanneries in Taylor County, with old photos.

- Map of Taylor County, Wisconsin, a plat map of the county from around 1900, showing owners, homes, sawmills, schools and churches at the time, courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society.