Door County, Wisconsin

Door County is the easternmost county in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2010 census, the population was 27,785.[4] Its county seat is Sturgeon Bay, making it one of three Wisconsin counties on Lake Michigan not to have a county seat with the same name.[5] The county was created in 1851 and organized in 1861.[6] It is named after the strait between the Door Peninsula and Washington Island. The dangerous passage, known as Death's Door, contains shipwrecks and was known to Native Americans and early French explorers. Door County is a popular Upper Midwest vacation destination.[7]

Door County | |

|---|---|

| |

Location within the U.S. state of Wisconsin | |

Wisconsin's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 45.02°N 87.01°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1851 |

| Named for | Porte des Morts |

| Seat | Sturgeon Bay |

| Largest city | Sturgeon Bay |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2,370 sq mi (6,100 km2) |

| • Land | 482 sq mi (1,250 km2) |

| • Water | 1,888 sq mi (4,890 km2) 80% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 27,785 |

| • Estimate (2019) | 27,668 |

| • Density | 12/sq mi (4.5/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Area code | 920 |

| Congressional district | 8th |

| Website | Official website |

| Wisconsin county code 15 FIPS county code 55029 | |

History

Native Americans and French

Porte des Morts legend

Door County's name came from Porte des Morts ("Death's Door"), the passage between the tip of Door Peninsula and Washington Island.[8] The name "Death's Door" came from Native American tales, heard by early French explorers and published in greatly embellished form by Hjalmar Holand, described a failed raid by the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) tribe to capture Washington Island from the rival Pottawatomi tribe in the early 1600s. It has become associated with shipwrecks within the passage.[9]

19th–20th century settlement

The 19th and 20th centuries saw the immigration and settlement of pioneers, mariners, fishermen, loggers, and farmers. The first white settler was Increase Claflin.[10] In 1851, Door County was separated from what had been Brown County.[11] In 1854 on Washington Island, the first post office opened in the county.[12] In 1855, four Irishmen were accidentally left behind by their steamboat, leading to the settlement of what is now Forestville.[13] In 1853, Moravians founded Ephraim as a religious community after Nils Otto Tank resisted attempts at land ownership reform at the old religious colony near Green Bay.[14] In the 19th century, a fairly large-scale immigration of Belgian Walloons populated a small region in southern portion of the county,[15] including the area designated as the Namur Historic District. They built small roadside votive chapels, some still in use today,[16] and brought other traditions over from Europe such as the Kermiss harvest festival.[17]

With the passage of the Homestead Act of 1862, people could purchase 80 acres of land for $18, provided they resided on the land, improved it, and farmed for five years. This made settlement in Door County more affordable.

When the 1871 Peshtigo fire burned the town of Williamsonville, sixty people were killed. The area of this disaster is now Tornado Memorial County Park, named for a fire whirl which occurred there.[18][19][20] Altogether, 128 people in the county perished in the Peshtigo fire.[11] Following the fire, some residents decided to use brick instead of wood.[21]

In 1885 or 1886, what is now the Coast Guard Station was established at Sturgeon Bay.[22][23] The small seasonally open station on Washington Island was established in 1902.[24]

As the period of settlement continued, Native Americans lived in Door County as a minority. The 1890 census reported 22 Indians living in Door County. They were self-supporting, subject to taxation, and did not receive rations.[25] By the 1910 census their numbers had declined to nine.[26]

In 1894 the Ahnapee and Western Railway was extended to Sturgeon Bay. In 1969, a train ran north of Algoma into the county for the last time,[27] although further south trains continued to operate until 1986.[28]

.jpg.webp)

Early tourism

From 1865 through 1870, three resort hotels were constructed in and near Sturgeon Bay along with another one in Fish Creek. One resort established in 1870 charged $7.50 per week (a little over $150 in 2020 dollars). Although the price included three daily meals, extra was charged for renting horses, which were also available with buggies and buggy-drivers.[29] Besides staying in hotels, tourists also boarded in private homes. Tourists could visit the northern part of the county by Great Lakes passenger steamer, sometimes as part of a lake cruise featuring music and entertainment.[30] Reaching the peninsula from Chicago took three days. The air surrounding the agricultural communities was relatively free of ragweed pollen because grain crops matured slowly in the cool climate and were harvested late in the year. This prevented late-season ragweed infestations in the stubble. This made it especially attractive to those suffering from hay fever in the city.[31]

Improved highways of crushed stone facilitated motor tourism in the early 1900s.[11] By 1909 at least 1,000 tourists visited per year.[32] In 1938 Jens Jensen cautioned about negative cultural impacts of tourism. He wrote, "Door County is slowly being ruined by the stupid money crazed fools. This tourist business is destroying the little bit of culture that was."[33]

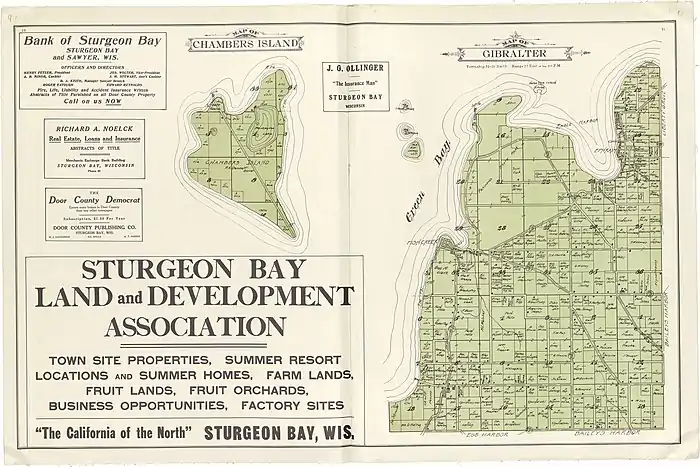

Orchard boosterism

In 1865, the first commercial fruit operation was established when grapes were cultivated on one of the Strawberry Islands. By 1895, a large fruit tree nursery was established and fruit horticulture was aggressively promoted. Not only farmers but even "city-bred" men were urged to consider fruit husbandry as a career. The first of multiple fruit marketing cooperatives began in 1897. In addition to corporate-run orchards, in 1910 the first corporation was established to plant and sell pre-established orchards. Although apple orchards predated cherry orchards, by 1913 it was reported that cherries had outpaced apples.[34]

Cherry crop labor sources

Women and children were typically employed to pick fruit crops, but the available work outstripped the labor supply. By 1918, it was difficult to find enough help to pick fruit crops, so workers were brought in by the YMCA and Boy Scouts of America. Cherry picking was marketed as a good summer camp activity for teenage boys in return for room, board, and recreation activities. One orchard hired players from the Green Bay Packers as camp counselors. Additionally, members of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and other native tribes were employed to pick fruit crops.[35][36] In addition to their pay, Native American families were given fruit that was too ripe for marketing, which they preserved and stored for long term use.[37] A Civilian Conservation Corps camp was established at Peninsula State Park during the Great Depression. In the summer of 1945, Fish Creek was the site of a POW camp under an affiliation with a base camp at Fort Sheridan, Illinois.[38][39][40] The German prisoners engaged in construction projects, cut wood, and picked cherries in Peninsula State Park and the surrounding area.[41] During a brief strike, the POWs refused to work. In response the guards established a "no work, no eat" policy and they returned to work, picking 11 pails per day and eventually totaling 508,020 pails.[42]

The Wisconsin State Employment Service established an office in Door County in 1949 to recruit Tejanos to pick cherries. Work was unpredictable, as cherry harvests were poor during certain years and workers were paid by the amount they picked. In 1951, the Wisconsin Department of Public Welfare conducted a study documenting conflict between migrant workers and tourists, who resented the presence of migrant families in public vacation areas.[43] A list of recommendations was prepared to improve race relations.[44] The employment of migrants continues to the present day. In 2013, there were three migrant labor camps in the county, housing a total of 57 orchard laborers and food processors along with five non-workers.[45]

20th–21st-century events

In 1905, the Lilly Amiot was in Ellison Bay with a load of freight, dynamite, and gasoline when it caught fire. After being cut loose, it drifted until exploding; the explosion was heard up to 15 miles away.[46]

In 1912, the barnstormer Lincoln Beachey demonstrated his biplane during the county fair; this is believed to be the first takeoff and landing in the county.[47]

In 1913, The Old Rugged Cross was first sung at the Friends Church in Sturgeon Bay as a duet by two traveling preachers.[48]

In 1919, the first Army-Navy hydrogen balloon race was won by an Army team whose balloon splashed down in the Death's Door passage. Two soldiers endured 10-foot waves for an hour before their rescue by a fisherman.[49]

In 1925, a cow in Horseshoe Bay named Aurora Homestead Badger produced 30,000 pounds of milk, at the time a world record for dairy cattle.[50]

In June 1938, aerial photos were taken of the entire county; in 2011 the photos were made available online.[51]

In 1941, the Sturgeon Bay Vocation School opened. It is now the Sturgeon Bay campus of Northeast Wisconsin Technical College.

In December 1959, the Bridgebuilder X disappeared after leaving a shipyard in Sturgeon Bay where it had been repaired. Its intended destinations were Northport and South Fox Island. Possible factors included lack of ballast and a sudden development of 11-foot waves. The body of one of the two crew members was found the following summer.[52]

In 2004, the county began a sister cities relationship with Jingdezhen in southeastern China.[53]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 2,370 square miles (6,100 km2), of which 482 square miles (1,250 km2) is land and 1,888 square miles (4,890 km2) (80%) is water.[54] It is the largest county in Wisconsin by total area.

The county has 298 miles (480,000 m) of shoreline, which in general is characterized by the escarpment on the west side. On the east side peat is followed by dunes and beaches of sand or gravel along the lakeshore.[55] During years with receding lake levels, flora along the shore demonstrates plant succession. The middle of the peninsula is mostly flat or rolling cultivated land. There are three distinct aquifers and two types of springs present in the county.[56][57]

The county covers the majority of the Door Peninsula. With the completion of the Sturgeon Bay Shipping Canal in 1881,[58] the northern half of the peninsula became an artificial island.[59] This canal is believed to have somehow caused a reduction in the sturgeon population in the bay due to changes in the aquatic habitat.[60] The 45th parallel north bisects the "island," and this is commemorated by Meridian County Park.[61][62]

| Niagara Escarpment | |||

| |||

Escarpment

Dolomite outcroppings of the Niagara Escarpment are visible on both shores of the peninsula, but the karst formations of the cuesta ridge are especially prominent on the Green Bay side as seen at the Bayshore Blufflands. South of Sturgeon Bay the escarpment separates into multiple lower ridges without as many larger exposed rock faces.[63] Many caves are found in the escarpment.[64][65] Beyond the peninsula's northern tip, the partially submerged ridge forms the Potawatomi Islands, which stretch to the Garden Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The largest of these is Washington Island. Most of them form the Town of Washington.[66]

The escarpment is an attractive location for quarrying, homes, and communications towers.[67] A former stone quarry on the escarpment five miles northeast of Sturgeon Bay is now a county park.[68]

High points

Eskers are only found in the far southwest corner of the county, but drumlins and small moraines also occur further up the peninsula.[69]

The 102 ft high Brussels Hill[70] (44.75166°N 87.59093°W, elevation 851 feet) is the highest point in the county.[71] The nearby Red Hill Woods is the largest remaining maple–beech forest in the area.[72]

Old Baldy (44.920344°N 87.20192°W) is the state's tallest sand dune[73] at 93 feet above the lake level.[74]

Soils and crops

The most common USDA soil association in the northern two-thirds of the county is the Summerville[lower-alpha 1]-Longrie[lower-alpha 2]-Omena.[lower-alpha 3][75] These associated soils typically are less than three feet deep. Altogether, thirty-nine percent of the county is mapped as having less than three feet (about a meter) to the dolomite bedrock. Because there is relatively little soil over much of the peninsula and the bedrock is fractured, snowmelt quickly enters the aquifer. This causes seasonal basement flooding in some areas.[76]

Both sale prices and rental values of agricultural land are lower than most Wisconsin counties.[77] The most important field crops by acres harvested in 2017 were hay and haylage at 25,197 acres, soybeans at 16,790 acres, corn (grain) at 15,371 acres, corn (silage) at 9,314 acres, wheat at 8,790 acres, oats at 2,610 acres, and barley at 513 acres.[78] Despite lower productivity for other forms of agriculture, in the early 1900s the combination of thin soils and fractured bedrock was described by area promoters as beneficial to fruit horticulture, as the land would quickly drain during wet conditions and provide ideal soil conditions for orchard trees.[34] For apples, the influence of the calcium-rich dolomite on the soil was expected to promote good color.[79]

Soils in the county are classified as "frigid" because they usually have an average annual temperature of less than 8 °C (46.4 °F). The implication of this classification is that county soils are expected to be wetter and have less microbial activity than soils in warmer areas classified as "mesic." County soils are colder than inland areas of Wisconsin due to the climate-moderating effects of nearby bodies of water.[80]

Gravel pits, minerals, and oil

The prevalence of shallow soils and exposed bedrock hinders agriculture but is beneficial for mining. As of 2016, there are 16 active gravel pits and quarries in the county. They produce sand, gravel, and crushed rock for roadwork and construction use.[81] Six of them are county-owned and produce 75,000 cubic yards annually.[82]

Minerals found in Door County include fluorite,[83] gypsum,[84] calcite,[85] dolomite,[86] quartz,[87] marcasite,[88] and pyrite.[89] Crystals may be found in vugs.[90]

On three occasions in the early 1900s oil was found within a layer of shale in the middle and southern part of the county.[91] Additionally, solid bitumen has been observed in dolomite exposed along the Lake Michigan shore.[92]

Pollution

The combination of shallow soils and fractured bedrock makes well water contamination more likely. At any given time, at least one-third of private wells may contain bacteria.[93]

Mines, prior landfills, and former orchard sites are considered impaired lands and marked on an electronic county map.[94] A different electronic map shows the locations of private wells polluted with lead, arsenic, and other contaminants down to the section level.[95]

Most air pollution in Door County comes from outside the county.[96] The stability of air over the Lake Michigan shore along with the lake breezes[lower-alpha 4] may increase the concentration of ozone along the shoreline.[97]

Fewer late spring freezes

The moderating effects of nearby bodies of water reduce the likelihood of damaging late spring freezes. Late spring freezes are less likely to occur than in nearby areas, and when they do occur, they tend not to be as severe.[98]

Climate data

- For climate charts and tables, see Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin § Climate and Washington Island (Wisconsin) § Climate

The county has a humid continental climate (classified as Dfb in Köppen) with warm summers and cold snowy winters. Data from the Peninsular Agricultural Research Station north of the city of Sturgeon Bay gives average monthly temperatures ranging from 68.7 °F (20.4 °C) in the summer down to 18.0 °F (−7.8 °C) in the winter.

Climate records

On January 7, 1967 Washington Island received 17 inches of snow, setting the county record for the greatest one-day snowfall.[99]

Ice accumulation during the winter of 2014 was the highest ever recorded on Lake Michigan.[100]

Tornadoes

Four tornadoes touched down between 1844 and 1880, and six from 1950 to 1989, but there were no fatalities in any of them. Two crossed the Door-Kewaunee county line.[101] From 1989 to 2019, there were 2 additional tornadoes, including the F3 "Door County tornado" which hit Egg Harbor in 1998.[102] Additionally there were 10 waterspouts between 1950 and 2018.[103]

| Date of Tornado | Time | F-Scale | Length | Width (yards)[104] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7/1/1956 | 12:05 PM CST | F2 | 10.6 miles | 50 yards |

| 7/25/1966 | 6:20 PM CST | F0 | 2 miles | 17 yards |

| 4/22/1970 | 9:10 PM CST | F2 | 2.3 miles | 500 yards |

| 4/22/1970 | 9:30 PM CST | F2 | 4.3 miles | 500 yards |

| 7/12/1973 | 7:30 AM CST | F1 | 0 miles | 100 yards |

| 6/8/1985 | 8:00 PM CST | F2 | 5 miles | 150 yards |

| 8/23/1998 | 5:30 PM CST | F3 | 5.1 miles | 1,300 yards |

| 7/13/2000 | 2:55 PM CST | F0 | 0.1 miles | 50 yards |

Weather monitoring

Weather in the county is reported by WXN69 (FM 162.425), the NOAA weather radio station in Sister Bay.[105] Green Bay and Lake Michigan ice thickness reports and forecasts are produced by NOAA.[106]

Weather monitors in the county report terrestrial and marine weather conditions:

Attractions

.jpg.webp)

In 1905, Theodore Roosevelt recommended that the Shivering Sands area be protected.[108] Today this area includes Whitefish Dunes, Kellner's Fen, Shivering Sands wetland complex,[109] and Cave Point County Park.[110] Hjalmar Holand, an Ephraim resident,[111] promoted Door County as a tourist destination in the first half of the 20th century. He served on a committee begun in 1927 to protect and promote historical sites,[112] and as a result of this effort the county historical society purchased lands that are now county parks, including Tornado Park, Robert LaSalle Park, Murphy Park, Increase Claflin Park, and the Ridges Sanctuary.[113]

Today, most tourists and summer residents come from the metropolitan areas of Milwaukee, Chicago, Madison, Green Bay, and the Twin Cities,[114] although Illinois residents are the dominant group both in Door County and further south along the eastern edge of Wisconsin.[115]

In 2003, researchers found that compared to other Wisconsin counties, Door County had a middling amount of inland water acreage, forestland, county-owned acreage, and rail trail mileage and a high number of golf courses, amusement businesses,[lower-alpha 5] and downhill ski hills and campgrounds.[116] Despite the high number of campgrounds the Wisconsin DNR in 2006 reported that "demand for camping far exceeds current supply."[117]

Recreational lands

Lands open to public use

Door County is home to six state parks. Four are on the peninsula: Newport State Park, northeast of Ellison Bay; Peninsula State Park, east of Fish Creek; Potawatomi State Park, along Sturgeon Bay; and Whitefish Dunes State Park along Lake Michigan. Two are located on islands: Rock Island State Park and Grand Traverse Island State Park.[lower-alpha 6] In addition to the nature centers located inside the state parks, there are three others outside the parks. There are four State Wildlife and Fishery Areas[lower-alpha 7] and also State Natural Areas that allow free public access.[121][lower-alpha 8]

Besides county,[122] town, and community parks,[123][124] there is a boy scout camp, a Christian camp,[125] and a public site operated by The Archaeological Conservancy.[126][127] A local land trust operates 14 privately owned parks open to the public,[128] and 3,277.3 acres (1326.3 ha) of privately owned lands are open to the public for hunting, fishing, hiking, sight-seeing and cross-country skiing under the Managed Forest Program.[129]

Beaches

- For further information, see Pollution in Door County, Wisconsin § Beach contamination and Door Peninsula § Lake breeze

Including both the Lake Michigan and Green Bay shores, there are 54 public beaches or boat launches[130] and 39 kayak launch sites,[131] leading to the area's promotion as "the Cape Cod of the Midwest."[132] 35 beaches are routinely monitored for water quality advisories.[133]

Although Door County has fewer sunny days than most counties in Wisconsin and Illinois, it also has less rainfall and lower summer temperatures,[134] making for an optimal beach-going climate.

Waters

Boating

In 2012, 8,341 registered boats were kept in the county. Most of the county boating accidents reported in 2012 occurred in Green Bay.[135] A 1989–90 study of recreational boating in Wisconsin found that the county's Green Bay and Lake Michigan waters had a higher frequency of Great Lakes boating than any other county bordering Lake Michigan or Lake Superior. The typical motor used in the county's Green Bay and Lake Michigan waters had a horsepower over 90, while the typical motor used for inland county waters had a horsepower under 50. Overall, boaters perceived county waters as uncrowded and boater satisfaction was average.[136]

An annual race is held for which participants build small plywood boats.[137]

The county's longest river canoe route is on the Ahnapee River from County H south to the county line.[138]

Some itineraries connecting the Great Loop around the eastern U.S. and through the Mississippi include stops in Door County.[139]

A charity holds sailing classes each summer.[140] 1972–1973 surveys of high school juniors and seniors in northeast Wisconsin found that students from Door County were more likely to use sailboats than students from other counties.[141]

Lakes and ponds

Besides Lake Michigan and Green Bay, there are 25 lakes, ponds, or marshes and 37 rivers, creeks, streams, and springs in the county.[142]

Wetlands

4,631 ha (11,400 acres) of Door Peninsula Coastal Wetlands are listed under the Ramsar Convention as wetlands of international importance.[143] The listing includes three areas previously recognized as "Wetland Gems."[144]

| Wetland | Access[145] |

|---|---|

| Baileys Harbor Swamp | privately owned, although some parcels at the edge of the swamp on the east of Highway 57 are owned by the DNR as part of Mud Lake State Natural Area[146] |

| Big Marsh (Gunnerson Marsh) | 31.1 acres of water; partly within a DNR State Natural Area[147] |

| Button Marsh | privately owned, 81.6 acres of Managed Forest Land[148] to the west of it |

| Coffee Swamp | 2.2 acres of water; mostly within a DNR State Natural Area[149] |

| Ephraim Swamp | privately owned, although Ephraim Creek which runs through the swamp is a Class II[lower-alpha 9] trout stream and is open to the public up to the ordinary high water mark.[150] |

| Gardner Swamp | Gardner Swamp Wildlife Area[151] has three access sites[152] and 160 acres of adjacent Managed Forest Land[153] |

| Greenwood Swamp | privately owned |

| Larson Swamp | privately owned |

| Little Marsh (Wickman Marsh) | 14 acres of water; DNR State Natural Area[147] |

| Kellner's Fen | 60 to 80 acres of water; largely owned by an entity allowing public access[154] |

| Maplewood Swamp | privately owned, but the Ahnapee Trail runs through part of it[155] |

| May Swamp | privately owned |

| Stony Creek Swamp | privately owned, but the Ahnapee Trail runs past the far south end[156] |

| Voecks Marsh | 19.1 acres of water; within the Ridges Sanctuary which charges admission[157] |

Recognized natural areas

There are 29 state-defined natural areas in the county.[121]

| SNA # | SNA Name | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 12 | Peninsula Park Beech Forest | [158] |

| 13 | Peninsula Park White Cedar Forest | [159] |

| 17 | The Ridges Sanctuary | [157] |

| 47 | Sister Islands | [160] |

| 57 | Toft Point | [161] |

| 90 | Newport Conifer-Hardwoods | [162] |

| 110 | Jackson Harbor Ridges | [163] |

| 125 | Mud Lake | [146] |

| 175 | Whitefish Dunes | [164] |

| 204 | Marshall's Point | [165] |

| 218 | Mink River Estuary | [166] |

| 233 | Moonlight Bay Bedrock Beach | [167] |

| 276 | Coffey Swamp | [149] |

| 284 | Baileys Harbor Boreal Forest and Wetlands | [168] |

| 335 | Kangaroo Lake | [169] |

| 377 | Bayshore Blufflands | [170] |

| 378 | Ellison Bluff | [171] |

| 379 | Europe Bay Woods | [172] |

| 381 | North Bay | [173] |

| 382 | Rock Island Woods | [174] |

| 383 | White Cliff Fen and Forest | [175] |

| 391 | Big and Little Marsh | [147] |

| 403 | Thorp Pond | [176] |

| 413 | Detroit Harbor | [177] |

| 543 | Logan Creek | [178] |

| 544 | Meridian Park | [179] |

| 554 | Little Lake | [180] |

| 559 | Cave Point-Clay Banks | [181] |

| 688 | Peninsula Niagara Escarpment | [182] |

| Select State Natural Areas | |||

| |||

Living plant collections

- This section is about cultivated plants. For wild plants and fungi, see Flora of Door County, Wisconsin

Living plant collections include the orchid project at The Ridges Sanctuary[183] in Baileys Harbor and the U.S. Potato Genebank and a public garden in Sevastopol.[184][185]

Vertebrate species lists

From 1971 through 1976, 11 species of small mammals were found at Toft Point,[186] the Newport State Park Mammals Checklist has 34 species,[187] and in 1972 44 mammals were listed for the entire county.[188] From 1981 through 1995, 7 species of frogs and toads were recorded in the county.[189] In 1992 six amphibians and eight reptiles were found in and around Potawatomi State Park.[190]

Unique vertebrates

Tamias striatus doorsiensis, a subspecies of eastern chipmunk, is only found in Door, Kewaunee, Northeastern Brown, and possibly Manitowoc counties.[192] In 1999, the Wisconsin Natural Heritage Inventory listed 24 aquatic and 21 terrestrial animals in Door County as "rare."[193]

Birds

As of 2018, 166 species of birds have been confirmed to live in Door County, excluding birds seen which lack the habitat to nest and must only be passing through.[194]

Reverse migration is occasionally observed in the county. When birds traveling north reach the tip of the peninsula and the islands beyond, the long stretches of water sometimes unnerves them. Instead of crossing over to the Garden Peninsula, they turn around and fly back down the peninsula.[195]

During the 20th century, thousands of herring gulls were banded on Hat Island[196] to determine their migratory patterns.[197] Banded birds were found as far north as Hudson Bay and as far south as Central America.[118]

Brood parasitism by red-breasted mergansers has been observed on Gravel and Spider islands and on another island known informally as "The Reef." They laid eggs into the nests of mallards, gadwalls, and lesser scaups.[198]

Rare bees

The sweat bee Lasioglossum sagax was collected on Ridges Road in 2006. Aside from a single collection from Manitowoc County in 2005, it had previously been found only in Colorado.[199]

The kleptoparasitic bee Stelis labiata is considered very rare.[200] It was collected at Toft point in 2006. This was only the second time the species had been found in Wisconsin; the earlier collection's county of origin is unknown.[201]

Horseshoe Bay Cave invertebrates

In 2014 an invertebrate survey of Horseshoe Bay Cave found an apparently groundwater-dwelling amphipod of the genus Crangonyx. Groundwater-dwelling Crangonyx species had never been documented in Wisconsin before.[202] A springtail of the genus Pygmarrhopalites (a genus name synonymous with Arrhopalites) was "found on the surface of drip pools." It appeared to be adapted to cave life and the study concluded that it "could represent an undescribed cave species."[203]

Toft Point invertebrates

In 2004, an invertebrate species list for Toft Point was published listing five isopods, four millipedes, six daddy longlegs, and 113 spiders. Of these, two of the millipedes and 14 of the spiders had never been documented in Wisconsin before.[204]

Spiders

The local climate may allow for the better survival of the northern black widow spider.[205]

Additionally, the county is home to the fishing spider Dolomedes tenebrosus, which can grow to about three inches, half the size of a tarantula.[206]

Other invertebrates

Kangaroo Lake State Natural Area has the largest breeding population of the endangered Hine's Emerald Dragonfly in the world.[207]

The Lake Huron locust lives on dunes in the county and is not found anywhere else in the state.[208]

From 1996 to 2001, researchers identified 69 species of snails in the county, including rare species.[209][138]

Research on apple maggots infesting cherries in Door County contributed to the study of sympatric speciation in the 1970s.[210]

In the 20th century, seven fish parasites were found in Hibbards Creek and 13 in Sturgeon Bay.[211]

During an experiment an estimated several thousand Mayflies hatched in Sawyer Harbor in 2016. They had previously been extirpated.[212]

By season

Although Door County has a year-round population of about 27,610, it experiences an influx of tourists each summer between Memorial Day and Labor Day, with over 2.1 million visitors per year.[213] Most businesses are targeted to tourism and operate seasonally. Based on room tax collections from 2017 to 2018, July is the busiest month of the year, although sales tax revenue is higher in August. The fewest room taxes are collected for January, and the fewest sales taxes are collected for April.[214]

Room occupancy for motels, resorts, and inns in Door County, July 2018 – August 2020[215]

.jpg.webp)

Springtime

Maple syrup production[216] was 983 gallons in 2017 from seven operations. This was similar to figures from 2012, but down from 2007 when 15 operations produced 2,365 gallons.[217]

The sucker run, which was a popular fishing event in the 19th century,[218] occurs in March and April.[219] Suckers may be taken by frame dip nets,[220] and the sucker run is also sought out as viewing opportunity.[221] Another permitted method of fishing for suckers is by speargun. In April 2018, the state speargun record for longnose sucker was taken by out of Door County waters on the Lake Michigan side. It weighed 3 pounds, 9.9 ounces and was 21.25 inches long.[222]

Another attraction is mushroom hunting on public land.[223][224] Additionally, as of 2017 there are two commercial mushroom operations.[225]

Summer

In 2017, there were ten operations growing 14 acres of strawberries.[226]

In 2017, there were eight operations harvesting five acres of fresh cut herbs, up from four acres in 2012.[227] Two of these operations grow lavender on Washington Island.[228][229]

In Baileys Harbor, religious tourism includes the Blessing of the Fleet.[230]

Door County has a history of strawberry,[231] apple, cherry, and plum growing that dates back to the 19th century.[232][34] Farmers were encouraged to grow fruit on the basis of the relatively mild climate on the peninsula. This is due to the moderating effects of the lake and bay on nearby land temperatures. U-pick orchards and fruit stands can be found along country roads when in season, and there are two cherry processors.[233]

However, the cherry and apple businesses have declined[234] since peaking in 1941[235] and 1964[34][236] respectively due to concerns about pesticides,[237] lack of migrant labor and a difficulty in finding local help, the closure of all processing plants save one, unpredictable harvests, the introduction of Drosophila suzukii, land-use competition with tourism and residential development, better growing conditions to the east in the fruit belt, such as the nearby Traverse City area,[238][34] and intentional destruction of a portion of the crop ordered by the processor in order to drive up prices.[239] In 2017, there were only 1,945 acres of tart cherry orchards, down from 2012 when there were 2,429 acres.[240]

Lightening bugs become common by the end of June.[241]

Fall

Additionally, there were 400 acres of apple orchards in 2017, down from 468 acres in 2012.[242] In 2017, there were 12 acres of pear orchards, spread among 11 operations.[243] In 2017, there was only one acre of plum orchards, spread among four operations.[244] In 2007, there were two acres of apricot orchards, spread among six operations.[245] Research on the development of cold-hardy peaches has continued since the 1980s.[246] In 2012, there were two acres of peach orchards, spread among seven operations.[247]

In 2017, there were 40 acres of vineyards, down from 78 acres in 2012.[248] The county was recognized as part of a larger federally designated wine grape-growing region in 2012.

In 2018, a county total of 4,791 deer were killed as a total of all deer hunting seasons, down from the total harvest of 5,264 deer in 2017.[249] Chronic wasting disease as of 2018 has never been detected within the county.[250]

Another autumn activity is leaf peeping.[251]

| Skiing and skating at Sturgeon Bay High School | |||

| |||

Winter

Winter attractions include ice fishing, sledding,[lower-alpha 10] cross-country skiing,[256] camping,[257] broomball,[258] pond hockey,[259] snowmobiling,[260] watching lake freighters in Sturgeon Bay,[261] and Christmas tree farms.[262][263] In 2017, 860 Christmas trees were cut, down from 1,929 in 2012.[264] Nearly 60% of the time, Door County has a white Christmas.[265]

Lighthouses

Including both lake and Green Bay shorelines, there are twelve lighthouses and sets of range lights. Most were built during the 19th century and are listed in the National Register of Historic Places: Baileys Harbor Range Lights, Cana Island Lighthouse,[266] Chambers Island Lighthouse, Eagle Bluff Lighthouse, Pilot Island Lighthouse, Plum Island Range Lights,[267] Pottawatomie Lighthouse, and Sturgeon Bay Canal Lighthouse. The other lighthouses in the county are: Boyer Bluff Lighthouse,[268] Baileys Harbor Light, Sherwood Point Lighthouse, and the Sturgeon Bay Canal North Pierhead Light.[269]

Historical sites

Thirteen historical sites are marked[270] in the state maritime trail for the area[271] in addition to eight roadside historical markers.[272] In Sturgeon Bay, the tugboat John Purves is operated as a museum ship. Including lighthouses, the county has 72 properties and districts listed on the National Register of Historic Places. There are 214 known confirmed and unconfirmed shipwrecks listed for the county,[273] including the SS Australasia, Christina Nilsson, Fleetwing, SS Frank O'Connor, Grape Shot, Green Bay, Hanover, Iris, SS Joys, SS Lakeland, Meridian, Ocean Wave, and Success. The SS Louisiana sank during the Great Lakes Storm of 1913.[274] Some shipwrecks are used for wreck diving.[275]

Buildings made from cordwood construction survive in the county, especially in the Bailey's Harbor area. Some, such as the Blacksmith Inn, are covered with clapboards on the outside.[276][277] It has been speculated that the use of stovewood in the county was associated with German immigrants and was also due to the lack of manpower needed to haul heavy logs.[278]

Food

| Some foods of Door County | |||

|

Agritourism and culinary tourism supports local food production.[279] Cooking classes are offered to tourists.[280]

Distinctive local foods include:

- cherry pie[281]

- Belgian pie[282]

- rhubarb pie[283]

- cherry kuchen[283]

- apple kuchen[283]

- rødgrød[283]

- rhubarb salad[283]

- rhubarb cake[283]

- rhubarb torte[283]

- cherry torte[283]

- raspberry marmalade Linzer torte[284]

- chicken caps–broiled mushroom caps coated in chicken spread and nuts[283]

- chocolate kraut cookies[283]

- cooked rhubarb juice diluted with water and sweetened with sugar[285]

- apricot pockets[286]

- cherry tarts[286]

- chopped cherry jam[287]

- cherry soup[288]

- Norwegian frugt suppe[289]

- cherry bread pudding[290]

- dried cherries[291]

- Limpa bread[290]

- skorpa[lower-alpha 11][290]

- æbleskiver–Icelandic pancakes[292][293]

- Norwegian and Swedish pancakes[294]

- green tomato jam[295]

- plum pudding with flaming brandy sauce[296]

- baked pears with cheese[297]

- cheese curds[298]

- fried perch[299]

- smoked chubs[300]

- fish boil–fuel oil flare up originated locally to entertain tourists[301][lower-alpha 12]

- booyah[302]–did not originate in Europe[303]

- Belgian trippe–sausage made with stomach lining[304]

- lapskaus–Norwegian potato stew[305]

- hash brown sandwich[304]

Scandinavian heritage

Scandinavian heritage-related attractions include The Clearing Folk School, two stave churches,[306] structures in Rock Island State Park furnished with rune-inscribed furniture,[307] and Al Johnson's Swedish Restaurant, which features goats on its grassy roof. In Ephraim, the Village Hall, the Moravian and Lutheran churches, and the Peter Peterson House are listed in the National Register of Historic Places, as is the L. A. Larson & Co. Store building in Sturgeon Bay. Although fish boils have been attributed to Scandinavian tradition,[308] several ethnicities present on the peninsula have traditions of boiling fish. The method common in the county is similar to that of Native Americans.[309][lower-alpha 13]

Industry

In Sturgeon Bay, industrial tourism includes tours of the Bay Shipbuilding Company,[310] CenterPointe Yacht Services[311][312] and other manufacturers.[313] In particular, Bay Ship owns a blue gantry crane that dominates the skyline.[314] A cheese factory in Clay Banks conducts public tours.[315]

Arts

Tourism supports an arts community, including weavers,[316] painters,[317] decorative artists,[318] blacksmiths,[319] actors,[lower-alpha 14] songwriters,[320] musicians,[321] and hymn-singers.[322]

A quilt trail along roadside barns was organized in 2010.[323]

The interesting landscape makes it an attractive target for photography. Several photographs have been used for commemorative stamps. A Town of Sturgeon Bay farm was featured on a stamp commemorating the Wisconsin Sesquicentennial in 2004,[324] and a cherry orchard near Brussels was featured on 2012 Earthscapes series stamp.

Astronauts on missions using every space shuttle and living in three different space stations have photographed the county. In 2014, one picture was featured as the NASA Earth Observatory Image of the Day.[100]

| Select astronaut photography of Door County | |||

| |||

Radio stations

Sports

| Door County Fairgrounds | |||

| |||

Sports tourism includes an underwater hockey team,[325] a motor racetrack in Sturgeon Bay,[326] and a semi-pro football team in Baileys Harbor.[327]

A county-wide men's baseball league has eight teams.[328]

High school sports teams play in the Packerland Conference, except for girls' swimming and golf, which compete in the Bay Conference.

In 2014, Door County ranked 264th out of all 3,141 U.S. counties by number of golf courses and country clubs. The county has nine courses, tying with 42 other counties. Door County had the 87th highest number of courses per resident of all U.S. counties.[329]

Motorcycling

In 2018, 3,476 motorcycles were registered in the county, up from 1,806 in 2018.[330] A local motorcycle club hosts a regional burning man event[331] involving a large wooden cow and maintains the adjacent Wisconsin Motorcycle Memorial.[332]

Flying

In 2019, 46 aircraft were registered in the county, most owned by individuals.[333] During the EAA AirVenture Oshkosh, a fish boil is held as a $100 hamburger event at the Washington Island Airport to entice AirVenture conventiongoers to land on the island.[334]

Ephraim no longer dry

In 2014–15, there were 257 liquor licenses in the county,[335] including one issued for a tavern on Washington Island which sells more Angostura bitters than any other tavern worldwide.[336] The county also has businesses that produce alcoholic beverages.[337] To encourage tourism, Ephraim residents passed referenda in 2016 to allow beer and/or wine sales within the village. Until then, Ephraim had been the state's last dry municipality.[338]

Economics of tourism

Door County's economy is similar to that of Bayfield, Iron, Oneida, Sawyer, and Vilas counties. These six northern Wisconsin counties have been categorized as having "forestry-related tourism"-based economies.[339]

An analysis comparing 1999 data for select Wisconsin counties found that Door County was especially strong in the retail of building and materials, groceries, apparel and accessories, miscellaneous retail, and restaurants. For services, it ranked strong in amusement, movie, and recreation and lodging. Door County ran a fiscal surplus in all categories to all other counties, with the exception of furniture & home furnishing, in which Door County had a leakage of sales to other counties.[340]

House pricing, real estate, and development

Between 2000 and 2017, prices for houses in Door County rose only 1.3% annually, less than the U.S. average of 2.5%.[341] In a 2008 survey of county residents, the most frequent local concern was the need to control rampant overdevelopment, including condos.[342] In 2006, nonresidents paid about 60% of the property taxes in the northern half of the county.[343]

Shoreline development

As of 2011, 7,889 residential buildings were located in within a quarter mile (402 meters) of the shore. Shoreline developments are vulnerable to erosion[344] and destruction from ice shoves.[345] Seiches on Green Bay cycle about every 11 hours but are highly variable and are capable of reversing the flow of water from rivers.[346]

Shoreline parcels, which tend to be the most highly valued real estate, are typically owned by non-Wisconsin residents unless they are public property.[347]

Effects of high property values

In 2017 the county had the second highest property values per capita in the state.[348] The high property values combined with low enrollment serve to punish local school districts in the state funding formula.[349] Since 1959, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction has wanted more school consolidation in Door County in order to achieve their statewide goal of having every district supported by a large tax base and offering a sufficiently comprehensive high school program. However, only the Southern Door School District complied with the DPI's expectations by consolidating into a single site in 1962.[350] As a result, the county's school districts often have referenda for additional property tax funding.[349]

For forested lands, high property values drive up property tax levies, which in turn encourages landowners to enroll their land in the Managed Forest Program to reduce their taxes.[351]

Effects of protected areas on nearby development

A 2012 report found that Door County's preserved open spaces reduced the likelihood that nearby land would be subdivided, but if it was subdivided, areas near the open space were divided into more parcels than those further away. It did not appear to affect agriculture-related development.[352]

Arts spending

In 2015, Door County arts and cultural organizations spent $9.7 million, of which 70.9% was spent locally, in addition to $15.0 million spent by attendees. An estimated 1,582 volunteers for arts and cultural organizations averaged 35.7 hours each. In 2015, 194,424 people attended arts and cultural events in the county, 78.0% of them non-residents. In 2016, the average arts event attendee from the county spent $28.96, while the average nonresident spent $90.53. In 2016, 50.6% of non-residents said the arts event was the primary reason they made the trip to the county. 66.0% of county resident attendees in 2016 were 65 or older, while 48.6% of non-resident attendees were 65 or older.[353]

Revenues

County spending in Door County is supported by property taxes, sales taxes, and state aid. In 2017, the county had the highest per capita property tax burden in the state,[348] although when compared by amount levied per $1,000 of property the tax was comparatively low with the county having the fifteenth lowest per capita property tax rate per $1,000 out of all 72 Wisconsin counties.[348] The county also collected $140 in per capita sales taxes in 2017, the second highest in the state,[348] and received the ninth highest level of per capita state financial assistance to the county government in 2015 figures.[348]

Expenses

Operating expenses of the Door County Tourism Zone Commission, 2008–2019[354]

In 2015, Door County had the third-highest level of per capita county spending in Wisconsin.[348] It was Wisconsin's only county with high per capita government spending in 2005 that did not also have a large low-income population. High per capita county government spending in Wisconsin is typically due to poverty.[357] Door County's spending can be explained by both the need to provide services to people present only during the tourism season[358] and by development patterns. A 2004 study showed that residential and commercial land tends to require more in government services than property taxes generate. These in turn are subsidized by taxes on industrial, agricultural, and open lands, which generally require few government services.[359]

The dispersal of residential developments is a compounding factor. A 2002 study found that Wisconsin town residents are typically subsidized by city and village residents.[360] The effect of seasonal residents on persons-per-housing unit figures was once masked by larger family sizes among year-round inhabitants. Beginning in the 1980 census the number of persons per housing unit fell below typical figures for Wisconsin as the number of children in the county dropped.[31]

Seasonality in both employment and housing

Door County unemployment rates during the summer and fall are considerably lower than in winter.[361][362] Annual earnings in Door County are typically less than similar jobs in other areas of Wisconsin. This has been attributed to the seasonal nature of much of the employment. For example, in 2009, it was found that people were 4.85 times more likely to be employed by hotels and motels in Door County as opposed to the rest of the nation.[363]

22.0% of the county's 13,728 employed workers[lower-alpha 15] in 2018 served in the leisure and hospitality sector, more than any other sector. However, because leisure and hospitality jobs tend not to pay very well, they only earned 12.9% of all wages earned in the county. In contrast, manufacturing employees received 24.5% of the wages paid in 2018, even though they only made up 17.0% of the workforce. This is despite the average annual wage for leisure and hospitality workers being 109.3% of the state average wage for leisure and hospitality in 2018. In contrast, workers employed in manufacturing received 86.7% of the state average wage for manufacturing. Wages in Door County trailed state averages for every sector except leisure and hospitality.[364] The effects of the low earnings are compounded by average housing prices; other areas in Wisconsin with low wages tend to have low housing prices.[365] The unaffordability of housing has been linked to the labor shortage problem, as new employees may be unable to afford housing and decide to leave.[366] A 2019 study found the county to have the eighth highest cost of living out of all Wisconsin counties.[367]

Homes, cabins, and cottages permitted for short term rentals, 2008 – May 2020[368]

Reliance on immigrant and foreign student labor

As high school enrollment in the county has dwindled,[lower-alpha 16] employers have turned to J-1 visas to fill seasonal positions instead.[371]

J-1 visas issued for work in Door County, 2016–2019

Because foreign workers brought in under the Summer Work Travel Program are sometimes housed in a different community from where they are employed, some have ended up bicycling 10–15 miles a day since they lack cars and the county has limited public transportation.[372] Additionally, illegal or undocumented immigrants who work in the tourism industry often lack drivers' licenses.[373] In 2012, Door County District Attorney Ray Pelrine said the "illegal immigrant workforce is now built into the structure of a lot of businesses here."[374]

For reported labor, people in the county tend to work in the county, and jobs in the county tend to be performed by county residents. According to 2011–2015 ACS data, out of 17 counties in northeastern Wisconsin, Door County had the second lowest percentage of residents commuting out-of-county to work. Only Brown County residents were less likely to commute out of their county to work. 89.08% of reported jobs Door County are performed by workers residing in the county, the highest percentage in the 17-county area. The low ranking has been attributed to the peninsula, which limits the directions people can practically commute.[375]

Geographic distribution of tourist spending

The economic impact of tourism is not the same throughout the county. A 2018 survey of tourists reported that Forestville and Brussels were the county's least visited communities.[376] Due to tourism's impact on restaurant prices, some residents of the more rural southern part of the county cannot afford to eat at restaurants in the northern part.[377]

Income inequality

Measures of income inequality show mixed results in Door County. Using the ACS five-year estimates from 2012 to 2016, the household income ratio between the 80th to 20th percentiles was only 3.76, the 352nd lowest such ratio out of 3,140 U.S. counties. On the other hand, 23.1% of all household income in the county was earned by the top 5th percentile, the 452nd greatest percentage out of 3,135 U.S. counties reporting data.[378]

Housing inequality

Most of the homeless in Door County are couch surfers, although in the summer many will camp or live out of their vehicles.[379]

The largest single-family house in the state is in Liberty Grove.[380] It was built in 1996 and is about 35,000 square feet. Although in 2005 it sold for about $20 million, in 2016 it sold for only $2.7 million,[381] and in 2019 was assessed at $2.625 million.[382] Additionally, an earth house in Sevastopol has been considered the "strangest home in Wisconsin."[383]

Elderly and housing

A 2019 report by the Wisconsin Bureau of Aging and Disability Resources based on data from 2013 to 2017 found that while only 12.7% of Door County residents aged 65 and older rented (compared to 23.5% statewide), 59.8% of those who did rent spent 30% or more of their income on rental costs (compared to 55.4% statewide).[384]

Transportation

Land

According to the Wisconsin Department of Transportation, in 2018 Door County had 1,270 miles of roadways.[385] In county figures for 2007 there were 1,455 named roads in the county.[386] In 2013 there were 588 lane miles[lower-alpha 17] of county trunk highways, 1743 lane miles of local roads, and 268 lane miles of state highways.[388] In Wisconsin DOT figures for 2018, there were 102 miles of state highways, 296 miles of county highways, and 872 miles of local roads.[385]

State highways

Average daily traffic by year; WIS–57 in Baileys Harbor[389]

The highest volumes of traffic in the county occur on Wisconsin Highway 42–57 from the junction of the separated highways in Nasewaupee to the Sturgeon Bay Ship Canal. The combined WIS 42–57 separates again at a junction in Sevastapol. Following this separation, WIS 42 continues along the western side of the peninsula and sees more traffic than WIS 57, which continues along the eastern side.[390] The two highways combine again at a junction in Liberty Grove.

Wisconsin Highway 42 (WIS 42)

Wisconsin Highway 42 (WIS 42) Wisconsin Highway 57 (WIS 57)

Wisconsin Highway 57 (WIS 57)- Door County Coastal Byway (WIS 42 and WIS 57) north of Sturgeon Bay to Northport is classified as a Coastal Byway.[391]

Rustic roads

- There are five rustic roads in the county.[392] In addition to state-recognized rustic roads, Liberty Grove manages a heritage roads program. As of 2019 there were 12 heritage roads in the town.[393]

Snowmobile

Non-motorized

- The Ahnapee State Trail connects Sturgeon Bay to Kewaunee, winter snowmobile access is dependent on weather and trail grooming.[396] Although the Ice Age Trail coincides with most of the Ahnapee State Trail, the Ice Age Trail forks away in the City of Sturgeon Bay and reaches its northern terminus at Potawatomi State Park.[397]

- WIS 42 and 57 are part of the Lake Michigan Circle Tour.[398]

- Egg Harbor operates a free public bicycle-sharing system, limited to daylight hours within the village during the tourist season.[399]

Bridges across Sturgeon Bay

- Sturgeon Bay Bridge, (also called Michigan Street Bridge) (11.5 feet clearance, overhead-truss, Scherzer-type, double-leaf, rolling-lift bascule)[400]

- Oregon Street Bridge (reinforced concrete slab, rolling lift bascule girder with mechanical driven center locks)[401]

- Bayview Bridge (monolithic concrete placed on structural deck with steel girder superstructure, open grating on deck, bascule)[402]

Air

A daily private shuttle service operates between Green Bay–Austin Straubel International Airport and Sturgeon Bay.[403] The nearest intercity bus station with regular service is in Green Bay.[404] There are eleven airports in the county, including private or semi-public airports.

- Door County Cherryland Airport (KSUE), public use, three miles west of Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin

- Ephraim–Gibraltar Airport (3D2), public use, one mile southwest of Ephraim, Wisconsin

- Washington Island Airport (2P2), public use

- Crispy Cedars Airport, Brussels (7WI8), private, but open to visitors with advance notice[405]

- Door County Memorial Hospital Heliport, allows for air ambulance service to the hospital from remote areas of the county[406] and for flying patients to Green Bay.

- Chambers Island Airport, private[407]

- Five other small airports[lower-alpha 18]

Ferries

- Washington Island is served by two ferry routes. The first route is to take a 30-minute ferry ride from the Door Peninsula to Detroit Harbor on the island from a freight, automobile, and passenger ferry that departs daily from the Northport Pier at the northern terminus of Highway 42. This ferry makes approximately 225,000 trips per year.[403] The second route is a passenger-only ferry that departs from the unincorporated community of Gills Rock on a 20-minute route.[413]

- Rock Island State Park is reachable by the passenger ferry Karfi from Washington Island.[414] (During winter Rock Island is potentially accessible via snowmobile and foot traffic.)

- Although Chambers Island has no regularly scheduled ferry, there are boat operators which transport people to the island on call from Fish Creek.

Boat ramps and marinas

- There are 30 public boat access sites in the county.[415] The Lake Michigan State Water Trail follows most county shorelines.[416]

Population and its health

2000 Census

As of the 2000 census,[417] there were 27,961 people, 11,828 households, and 7,995 families residing in the county. The population density was 58 people per square mile (22/km2). There were 19,587 housing units at an average density of 41 per square mile (16/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 97.84% White, 0.19% Black or African American, 0.65% Native American, 0.29% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.33% from other races, and 0.69% from two or more races. 0.95% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 39.4% were of German and 10.3% Belgian ancestry. A small pocket of Walloon speakers forms the only Walloon-language region outside of Wallonia and its immediate neighbors.[418][419]

Out of a total of 11,828 households, 58.10% were married couples living together, 6.50% had a female householder with no husband present, and 32.40% were non-families. 28.10% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.70% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.33 and the average family size was 2.84.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 2,948 | — | |

| 1870 | 4,919 | 66.9% | |

| 1880 | 11,645 | 136.7% | |

| 1890 | 15,082 | 29.5% | |

| 1900 | 17,583 | 16.6% | |

| 1910 | 18,711 | 6.4% | |

| 1920 | 19,073 | 1.9% | |

| 1930 | 18,182 | −4.7% | |

| 1940 | 19,095 | 5.0% | |

| 1950 | 20,870 | 9.3% | |

| 1960 | 20,685 | −0.9% | |

| 1970 | 20,106 | −2.8% | |

| 1980 | 25,029 | 24.5% | |

| 1990 | 25,690 | 2.6% | |

| 2000 | 27,961 | 8.8% | |

| 2010 | 27,785 | −0.6% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 27,668 | [420] | −0.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[421] 1790–1960[422] 1900–1990[423] 1990–2000[424] 2010–2019[4] | |||

For every 100 females there were 97.10 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 94.50 males. In the county, the population was spread out, with 22.10% under the age of 18 (a decrease from 25.9% being under the age of 18 in the 1990 census[425]), 6.10% from 18 to 24, 25.40% from 25 to 44, and 27.70% from 45 to 64.

Births, abortions, deaths, migration

In 2017, there were 217 births, giving a general fertility rate of 59 births per 1000 women aged 15–44, the 49th highest rate out of 72 Wisconsin counties.[426] Additionally, there were eleven reported induced abortions performed on women of Door County residence in 2017.[427]

Between April 2010 and January 2019, there were an estimated 1,869 births and 2,904 deaths in the county. Although the greater number of deaths served to decrease the population by an estimated 1,035 people, this was more than offset by a net gain of 1,900 people who moved in from outside the county. Altogether, the population increased by an estimated 865 persons during this period.[428]

Most elderly and youthful communities

From ACS data from 2014 to 2018, the most elderly community in the county was the village of Ephraim with a median age of 65.4, the seventh most elderly out of all 1965 cities, towns, and villages having available data. Following Ephraim was Egg Harbor with a median age of 64.0, the 14th most elderly in the state, Sister Bay with a median age of 63.4, tied with Sherman in Iron County as the 18th most elderly, Washington Island with a median age of 62.9, tied with Union in Burnett County as the 22nd most elderly, Liberty Grove with a median age of 62.4, tied with Lakewood in Oconto County as the 26th most elderly, Egg Harbor with a median age of 59.8, tied with three other towns as the 55th most elderly, Gibraltar with a median age of 59.4, tied with the town of Raddison in Sawyer county as the 64th most elderly, and Bailey's Harbor with a median age of 58.5, tied with Big Bend in Rusk County as the 83rd most elderly.

The youngest community in Door County was the village of Forestville with a median age of 39.0. It tied with 12 other communities as the 429th youngest community in the state. Following the village of Forestville was the city of Sturgeon Bay with a median age of 42.8, tied with 9 other communities as the 742nd youngest in the state, Brussels with a median age of 46.9, tied with 8 other communities as the 1163rd youngest in the state, the town of Forestville with a median age of 47.4, tied with 9 other communities as the 1222nd youngest in the state, and Gardner with a median age of 49.4, tied with 15 other communities as the 1434th youngest in the state.[429]

| Children, Sturgeon Bay, 1917 | |||

| |||

Based on ACS data from 2013 to 2017, the county had a median age of 52.4 years old, tied with Florence as the fifth most elderly of all Wisconsin counties.[384] This was an increase from the 2000 census, which reported a county median age of 43 years. In the 2000 census, 18.70% of the county population was 65 years of age or older. By 2015, the percentage of elderly climbed, with 25.8% of the population being 65 or older, the third highest in the state.[348]

Declining youth and overall population

According to ACS estimates, the number of people under 18 in the county dropped from 5,119 in 2010 to 4,479 in 2017.[430] In 2013, a researcher predicted that by 2040, the county's population would decline 4.2%, the 10th-largest percentage decline among all Wisconsin counties.[431]

From 2013 to 2017, 36.8% of the 9,358 households in the county included children, based on the ACS 5-year estimate, compared to 44.2% for Wisconsin in 2017, based on the ACS one-year estimate.[432]

Declining public school enrollment

With the exception of the preschool program in Sevastopol, all county districts saw enrollment declines from 2000 to 2019 at the elementary, middle, and high school levels.[433] The Door County Charter School in Sturgeon Bay is not listed as it was only in operation from 2002 to 2005.[434]

| District | School | 2000 enrollment | 2019 enrollment | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gibraltar School District | Gibraltar High School | 233 | 192 | -17.6% |

| Gibraltar School District | Gibraltar Middle School | 167 | 84 | |

| Gibraltar School District | Gibraltar Elementary School | 293 | 278 | |

| Gibraltar School District | Gibraltar, combined statistics for the elementary and middle schools | 460 | 362 | -21.3% |

| Sevastopol School District | Sevastopol High School | 270 | 194 | -25.6% |

| Sevastopol School District | Sevastopol Elementary School (2000, K-5; 2018, K-6) | 284 | 258 | |

| Sevastopol School District | Sevastopol Junior High (7–8) in 2000; Sevastopol Middle School (6–8) in 2018 | 102 | 122 | |

| Sevastopol School District | Sevastopol, combined statistics for elementary and jr. high/middle school (K-8) | 386 | 380 | -1.6% |

| Sevastopol School District | Sevastopol Special Education, 2000, in 2018 the name is Sevastopol Pre-School | 13 | 28 | 115.4% |

| Southern Door School District | Southern Door High School | 453 | 331 | -26.9% |

| Southern Door School District | Southern Door Middle School | 298 | 279 | -6.4% |

| Southern Door School District | Southern Door Elementary School | 576 | 463 | -19.6% |

| Sturgeon Bay School District | Sturgeon Bay High School | 515 | 389 | -21.0% |

| Sturgeon Bay School District | T. J. Walker Middle School | 350 | 253 | -27.1% |

| Sturgeon Bay School District | Sunset Elementary School (in 2018, PreK–K) | 197 | 157 | |

| Sturgeon Bay School District | Sawyer Elementary School (in 2018, 1–2) | 164 | 131 | |

| Sturgeon Bay School District | Sunrise Elementary School (in 2018, 3–5) | 214 | 208 | |

| Sturgeon Bay School District | Sturgeon Bay, combined statistics for Sunset, Sawyer, and Sunrise Elementary Schools | 575 | 496 | -13.7% |

| Washington School District | Washington Island Elementary | 87 | 53 | -39.1% |

| Washington School District | Washington Island High School | 37 | 27 | -27.0% |

| All county districts | 4,253 | 3,453 | -18.8% |

Declining high school enrollment[433][lower-alpha 21] has been blamed for the shortage of seasonal workers, and credited with prompting the expansion of the J-1 visa program.[435][lower-alpha 22]

Total 9–12 enrollment at all five Door County high schools, 2000–2019

Marriages

Five-year ACS data from 2012 to 2016 show that an estimated 24.6% of women aged 45–54 in the county had never been married, the 69th highest percentage of never-married women in this age bracket out of 3,130 U.S. counties reporting data. The ACS estimate also found that 75.9% of women aged 35–44 were married, the 389th highest number of married women in this age bracket out of 3,136 counties reporting data, and that the county was tied with three other counties in having the 180th lowest percentage of births to unmarried women out of 3,021 counties reporting data. 13.4% of births were to unmarried women.[378]

In 2015, the county had the 20th-most marriages and 43rd-most divorces out of all Wisconsin counties. August and September tied as the months with the most weddings, with 75 each.[436] In 2016 the county was the 45th-most populous in the state.[437]

Religious statistics

In 2010 statistics, the largest religious group in Door County was the Catholics, with 9,325 adherents worshipping at six parishes, followed by 2,982 ELCA Lutherans with seven congregations, 2,646 WELS Lutherans with seven congregations, 872 Moravians with three congregations, 834 United Methodists with four congregations, 533 non-denominational Christians with six congregations, 503 LCMS Lutherans with two congregations, 283 LCMC Lutherans with one congregation, 270 Converge Baptists with three congregations, 213 Episcopalians with one congregation, 207 UCC Christians with one congregation, and 593 other adherents. Altogether, 69.3% of the population was counted as adherents of a religious congregation.[439]

In 2014, Door County had the 719th-most religious organizations per resident out of all 3,141 U.S. counties, with 34 religious organizations in the county.[329]

Median incomes

According to 2014–2018 ACS data, four communities had median incomes lower than the county median income of $58,287. Of these, Sister Bay had the lowest median household income at $40,944, ranking the 135th lowest in the state out of 1,951 cities, villages, and towns which had available data. Following Sister Bay was the village of Forestville at $49,500 and ranking 444th lowest in a tie with New London in Waupaca County, the city of Sturgeon Bay at $52,917 and ranking 610th lowest, and Washington Island at $55,341 and ranking 737th lowest.

Gibraltar had the highest median income in the county at $80,602, the 232nd highest in the state, followed by Ephraim at $77,500 and ranking 305th highest, Egg Harbor at $75,833 and ranking 343rd highest, and Jacksonport at $70,625 at 483rd highest.[429]

In 2016, the county had the third highest per capita personal income in the state[348] and in 2015 it had the seventh lowest poverty level in the state.[348] In 2015, 39.0% of the population had an associate degree or more, making Door County the 12th most educated out of all 72 Wisconsin counties.[348]

Cattle and deer

In 2018, there were an estimated 23,500 head of cattle in the county.[440] In 2017, Door and Kewaunee counties were reported to have equal deer-to-human ratios, although Kewaunee County had a considerably greater cow-to-human ratio.[441]

Public health

2019 drug charges by type of drug[442]

Minors receiving county-managed

psychiatric medication, 2014–2019[443]

In most measures of public health for 2015, the county has figures as healthy as or healthier than those of the entire state.[444] According to calculations based on 2010–2014 data, children born in Door County have a life expectancy of 80.9 years, the ninth highest of Wisconsin's 72 counties.[445] From 2000 to 2010, the county's premature death rate for people under 75 fell 35.0%, the second-greatest reduction in Wisconsin.[446]

In December 2018, Door County residents aged 18–64 were less likely to be receiving government payments for disability than the averages for Wisconsin and the United States as a whole.[447] Five-year ACS estimates for 2012–2016 found that Door County tied with 24 other counties in having the 573rd lowest percentage of disabled residents under 65 out of all 3,145 U.S. counties. 9.3% were disabled.[378]

From 2009 to 2013 the county had the highest skin cancer rate in the state.[448]

In 2017, three people died from drug abuse, up from two in 2016.[449]

A CDC survey of people reporting frequent mental distress (14–30 mentally unhealthy days in the last 30 days, data aggregated over 2003–2009) found that people in Door County were more likely to be distressed than those in most Wisconsin counties, but less likely to be distressed than those in the heavily urbanized southeast portion of the state.[450]

With a rate of 9.53 county-medicated children per 1000 children, Door County had the fourth highest rate in the state out of all 27 counties and multi-county social services agencies reporting statistics on the psychiatric medication of minors in 2019. Out of the 43 medicated minors in 2019, 26 were female and 17 were male, 36 were white, 5 were of an unknown race, and 2 belonged to other races.[451]

In 2019, the county Behavioral Health Unit had 185 clients, up from 142 in 2018.[2]

Tick-borne illnesses

A study of the risk of getting Lyme disease in Door County between 1991 and 1994 found it to be relatively low, possibly due to its having less vegetation than most Wisconsin counties.[452] From 2015 through 2017 reported cases of Lyme disease increased from 4 cases in 2015 to 30 cases in 2017.[453] As of 2017, no cases of babesiosis have been reported in the county, but the range of this disease now includes Brown County after considerable expansion into Northeastern Wisconsin from 2001 to 2015.[454][449]

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic was reported to have reached the county on March 30, 2020. As of February 3, 2021, the Door County Public Health Office reported 2,362 cases, 80 hospitalizations, and 18 deaths of county residents, with 2,389 recoveries.[455]

Vehicle accidents

Most fatal or incapacitating vehicle accidents in the county between 2010 and 2014 involved visitors. 6% of those involved in these accidents were from Illinois, 3% from Florida, and 7% from other states.[459] In a study of car accident data from 1992 to 2001, the risk of incurring a severe traffic injury during a stretch of driving was found to be lower in Door County than in Kewaunee County, but Door County had more fatalities per 100 people severely injured than Kewaunee, Brown, Manitowoc, and Sheboygan counties. This was thought to be due to the relatively long distance it takes to get people injured in Door County to treatment, as the nearest hospital with a high level of trauma certification was St. Vincent Hospital in Green Bay.[460] Currently, St. Vincent's and Aurora BayCare are certified as level II trauma centers.[461]

From 2014 through 2017, fatalities and serious injuries especially occurred on the western side of the peninsula between the bay of Sturgeon Bay and Egg Harbor.[390]

From January 2001 through December 2020, there were 67 collisions reported in the county involving fatalities. Out of 66 of the fatal collisions, 29 occurred south of the canal, 36 occurred on the peninsula north of the canal, and one occurred on Washington Island. One additional fatal crash was not mapped by the state Department of Transportation. Out of 66 of the fatal collisions, 29 occurred along or at the intersection of the main route of a state highway, not including business routes. Three fatal crashes involving motorcycles occurred, with one each in the towns of Jacksonport, Baileys Harbor, and Liberty Grove.[456]

From January 2010 through December 2020 there were 329 reported collisions involving alcohol within the county, which resulted in 9 fatalities and 198 injuries.[456]

From January 2010 through December 2020 there were 47 reported collisions involving drugs. Out of 45 collisions involving drugs, 10 occurred south of the canal (with one involving fatalities), 34 occurred on the peninsula north of the canal, (with three involving fatalities) and one crash with no fatalities occurred on Washington Island. Two additional crashes involving drugs were not mapped.[456]

From January 2010 through December 2020 there were 48 reported collisions involving bicycles. Out of 46 of the collisions involving bicycles, 5 occurred south of the canal, 37 occurred on the peninsula north of the canal, and four occurred on Washington Island. Two additional crashes involving bicycles were not mapped.[456]

From January 2010 through December 2020 there were 29 reported collisions involving work zones, resulting in 12 injuries and no fatalities.[456]

From January 2010 through January 2020 there were 44 reported collisions involving pedestrians. Out of 34 of the crashes involving pedestrians, 6 occurred south of the canal and 28 occurred on the peninsula north of the canal. 10 additional crashes involving pedestrians were not mapped.[456]

Crime

In 2019 there were 176 felony cases prosecuted by the county, up from 171 in 2018. Of these, 3 went to trial, down from 6 in 2018.[2]

The county has been a focus of sex-trafficking enforcement efforts.[462] From 2015 to 2019 there were no reports of sex-trafficking in the county.[463]

Adult Protective Services referrals, 2007–2019 and annual WATTS reviews[lower-alpha 23] conducted for persons under court-ordered supervision, 2008–2018[464]

referrals to APS WATTS reviewsAdult Protective Services

In 2012, 58% of referrals alleging the abuse and neglect of the elderly or elders at risk involved self-neglect. 15.1% were for financial exploitation, 11.9% were for neglect, 7.9% were for emotional abuse, 5.6% were for physical abuse, and 0.8% were for sexual abuse.[465]

Child maltreatment

In 2019, there were 433 complaints of child neglect, abuse, or emotional damage/abuse in the county. At 9.6 reports per 100 children, Door County had the ninth highest rate of allegations out of all 72 Wisconsin counties. Among the 433 allegations, 105 passed the screening and were considered credible enough to investigate. At 2.3 screened-in complaints per 100 children, Door County ranked the 23rd highest in the state.[466]

113 reports were placed by "not documented" sources, 98 were placed by educational personnel, 47 were placed by mental health professionals, 45 were placed by legal/law enforcement, 26 were placed by others, 23 were placed by social services workers, 22 were placed by medical professionals, 17 were placed by relatives, and 16 were placed by parents of the child victims.[467]

Child welfare cases resulting in ongoing social services supervision of the family, 2007–2012 and total child welfare cases investigated, 2007–2014[468]

Decisions were made about whether to investigate the complaints 87 times within 24–48 hours and 309 times within five business days. The number of complaints peaked in February, April, July, and October, with the month of October having the greatest number of allegations at 57.[467]

321 reports (93 deemed worth investigating) concerned a white child victim, while 20 reports (6 deemed worth investigating) concerned African American children. Most reports concerning African American children were generated by educational personnel. 103 reports (12 considered worth investigating) concerned children of a race besides white or African American, or whose race was unknown or was not provided. Due to multiracial children, the total number exceeds 433.[467]

198 of the reports alleged neglect, with 56 of the reports coming from "not documented" sources, 36 reports from educational personnel, and 23 reports from legal/law enforcement. 137 of the reports alleged physical abuse, with 46 reports from educational personnel, 27 reports from "not documented" sources, and 21 reports from mental health professionals. 94 of the reports alleged sexual abuse, with 28 from "not documented" sources, 17 from mental health professionals, 15 from legal/law enforcement, and 10 from educational personnel. Out of the 43 reports alleged emotional damage/abuse, 15 came from educational personnel.[467]

In 2012, 34 children were held for 72 hours, up from 32 children in 2011.[469]

Communities

City

- Sturgeon Bay (county seat)

Villages

Towns

- Baileys Harbor (Cana Island is in the Town of Baileys Harbor)

- Brussels

- Clay Banks

- Egg Harbor

- Forestville

- Gardner

- Gibraltar (the Strawberry Islands, Hat, Horseshoe, and Chambers Island are in the Town of Gibraltar)

- Jacksonport

- Liberty Grove (Gravel Island, Spider Island, and the Sister Islands are in the Town of Liberty Grove)

- Nasewaupee

- Sevastopol

- Sturgeon Bay

- Union

- Washington Island

Unincorporated communities

Absorbed into Sturgeon Bay

- Sawyer

- Stevens Hill

Abandoned

Census-designated places

Adjacent counties

By land

- Kewaunee County - south

In Green Bay

- Brown County - southwest[470]

- Oconto County - west

- Marinette County - northwest

- Menominee County, Michigan - northwest

Along the Rock Island Passage

- Delta County, Michigan - north

In Lake Michigan

- Leelanau County, Michigan - northeast and east

- Benzie County, Michigan - southeast

Notable people

- Robert C. Bassett (1911–2000), U.S. presidential advisor[471]

- Jule Berndt (1924–1997), pastor

- Norbert Blei (1935–2013), writer

- Gene Brabender (1941–1996), baseball player[472]

- Hans Christian (born 1960), musician

- Jessie Kalmbach Chase (1879–1970), painter

- Eddie Cochems (1877–1953), "Father of the Forward Pass"

- Erik Cordier (born 1986), baseball player

- Katherine Whitney Curtis (1897–1980), originator of synchronized swimming

- Mary Maples Dunn (1931–2017), historian

- Jim Flanigan (born 1971), football player[473]

- Lou Goss (born 1987), racecar driver

- Chris Greisen (born 1976), Milwaukee Iron quarterback (AFL)

- Nick Greisen (born 1979), Denver Broncos linebacker (NFL)