Vanguard (rocket)

The Vanguard rocket[1] was intended to be the first launch vehicle the United States would use to place a satellite into orbit. Instead, the Sputnik crisis caused by the surprise launch of Sputnik 1 led the U.S., after the failure of Vanguard TV-3, to quickly orbit the Explorer 1 satellite using a Juno I rocket, making Vanguard 1 the second successful U.S. orbital launch.

Vanguard rocket on Pad LC-18A | |

| Function | Satellite launch vehicle |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Glenn L. Martin Company |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Size | |

| Height | 21.9 metres (72 ft) |

| Diameter | 1.14 metres (3 ft 9 in) |

| Mass | 10,050 kilograms (22,160 lb) |

| Stages | 3 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | |

| Mass | 11.3 kg (25 lb) |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Retired |

| Launch sites | Cape Canaveral, LC-18A |

| Total launches | 11 |

| Success(es) | 3 |

| Failure(s) | 8 |

| First flight | 23 October 1957 (Vanguard 1: 17 April 1958) |

| Last flight | 18 September 1959 |

| First stage – Vanguard | |

| Length | 13.4 m (44 ft) |

| Diameter | 1.14 m (3 ft 9 in) |

| Empty mass | 811 kg (1,788 lb) |

| Gross mass | 8,090 kg (17,840 lb) |

| Engines | 1 General Electric GE X-405 |

| Thrust | 125,000 N (28,000 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 248 s (2.43 km/s) |

| Burn time | 144 seconds |

| Fuel | LOX / Kerosene (RP-1) |

| Second stage – Delta | |

| Length | 5.8 m (19 ft) |

| Diameter | 0.8 m (2 ft 7 in) |

| Empty mass | 694 kg (1,530 lb) |

| Gross mass | 1,990 kg (4,390 lb) |

| Engines | 1 Aerojet General AJ10-37 |

| Thrust | 32,600 N (7,300 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 261 s (2.56 km/s) |

| Burn time | 120 seconds |

| Fuel | UDMH / Nitric acid (WIFNA) |

| Third stage – Grand Central Rocket Company or Allegany Ballistics Laboratory (last) | |

| Length | 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) |

| Diameter | 0.8 m (2 ft 7 in) |

| Empty mass | 31 kg (68 lb) |

| Gross mass | 194 kg (428 lb) |

| Motor | 1 |

| Thrust | 10,400 N (2,300 lbf) |

| Specific impulse | 230 s (2.3 km/s) |

| Burn time | 30 seconds |

| Fuel | Solid |

Vanguard rockets were used by Project Vanguard from 1957 to 1959. Of the eleven Vanguard rockets which the project attempted to launch, three successfully placed satellites into orbit. Vanguard rockets were an important part of the Space Race between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Overview

In 1955, the United States announced plans to put a scientific satellite in orbit for the International Geophysical Year (IGY) in 1957–1958. The goal was to track the satellite as it performed experiments.[2] At that time, there were three candidates for the launch vehicle: The Air Force's SM-65 Atlas, a derivative of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency's SSM-A-14 Redstone, and a Navy proposal for a three-stage rocket based on the RTV-N-12a Viking sounding rocket.[3][4]

The RAND Corporation, Air Force and CIA had long pursued the idea of a reconnaissance satellite.[5] Such a program was under way, Weapon System 117L, which was top secret compartmented.[6] One problem with reconnaissance was the question of legality: Was there "freedom of space" or did a nation's airspace end when space is entered?[2] The National Security Council backed the IGY satellite because it would make good cover for WS117L and set a precedent of freedom of space peaceful civilian satellite. At the same time the NSC stressed that the IGY satellite must not interfere with military programs.[7] The Army's Redstone-based proposal would likely be the first one ready for a satellite launch. Its connection with German-born scientist Wernher von Braun, however, was a public-relations risk.[8][4] In any case, the Atlas and Redstone ballistic missiles were top-priority military projects, which were not to be hindered by pursuing a secondary space launch mission.[9] Milton Rosen's Vanguard was a project at the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), which was regarded more as a scientific than a military organization. Rosen and Richard Porter (IGY satellite chief and head of the American Rocket Society) both lobbied for the Vanguard and against using the Atlas or von Braun's rockets.[10] They emphasized the non-military goals of the satellite program. Besides the public-relations aspect, a non-military satellite was considered important, because a discussion of whether overflights of foreign countries by satellites were legal or illegal was to be avoided.[11]

In August or September 1955, the DOD Committee on Special Capabilities chose the NRL proposal, named Vanguard, for the IGY project. The Martin company, which had also built the Viking, became prime contractor for the launch vehicle.[12] The Vanguard rocket was designed as a three-stage vehicle. The first stage was a General Electric X-405 liquid-fueled engine (designated XLR50-GE-2 by the Navy), derived from the engine of the RTV-N-12a Viking. The second stage was the Aerojet General AJ10-37 (XLR52-AJ-2) liquid-fueled engine, a variant of the engine in the RTV-N-10 Aerobee. Finally, the third stage was a solid-propellant rocket motor. All three-stage Vanguard flights except the last one used a motor built by the Grand Central Rocket Company. Vanguard had no fins, and the first and second stages were steered by gimbaled engines. The second stage housed the vehicle's telemetry system, the inertial guidance system and the autopilot. The third stage was spin-stabilized, with the spin imparted by a turntable on the second stage before separation.

The Vanguard's second stage served for decades as the Able and Delta second stage for satellite launch vehicles.[13] The AJ10 engine which made up those stages was adapted into the AJ10-137, which was used as the Apollo Service Module engine. The AJ10-190, adapted from the Apollo spacecraft was used on the Space Shuttle for orbital maneuvers.[14] The AJ10-160 is to be repurposed for use on NASA's upcoming Orion spacecraft.

Launch summary

The first two flights of the Vanguard program, designated Vanguard TV-0 and Vanguard TV-1, were actually the last two remaining RTV-N-12a Viking rockets modified. Vanguard TV-0, launched on 8 December 1956, primarily tested new telemetry systems, while Vanguard TV-1 on 1 May 1957, was a two-stage vehicle testing separation and ignition of the solid-fueled upper stage of Vanguard. Vanguard TV-2, launched on 23 October 1957, after several abortive attempts, was the first real Vanguard rocket. The second and third stages were inert, but the flight successfully tested first/second-stage separation and spin-up of the third stage. However, by that time, the Soviet Union had already placed the Sputnik 1 satellite into orbit, and so project Vanguard was more or less forced to launch its own satellite as soon as possible. Therefore, a very small experimental satellite (derisively called the "grapefruit" by Nikita Khrushchev, and weighing only 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb)) was added to Vanguard TV-3, which was to be the first test of an all-up Vanguard rocket. Although the NRL and Glenn L. Martin Company tried to emphasize that the Vanguard TV-3 mission was a pure test flight (and one with several "firsts"), everyone else saw it as the first satellite launch of the Western world, billed as "America's answer to Sputnik". Wernher von Braun angrily said about the Sputnik launch: "We knew they were going to do it. Vanguard will never make it. We have the hardware on the shelf. We can put up a satellite in 60 days".[15]

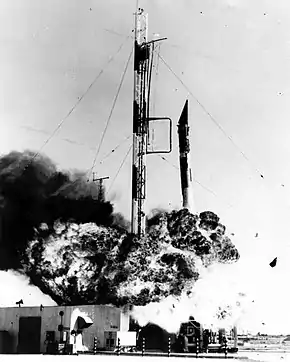

On 6 December 1957, the US Navy launched Vanguard TV-3 rocket, carrying a 1.5 kilograms (3.3 lb) satellite, from Cape Canaveral. It only reached an altitude of 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) before it fell and exploded. The satellite was exploded from the top of the rocket, landed in bushes near the pad, and began transmitting signals, leading New York Journal-American columnist Dorothy Kilgallen to remark "Why doesn't somebody go out there, find it, and shoot it?"[16] The American press called it Kaputnik.[17]

Investigation into the accident concluded that inadequate fuel tank pressure had allowed hot exhaust gases to back up into the injector head and destroy it, causing complete loss of engine thrust. After the failure of Vanguard TV-3, the backup vehicle, Vanguard TV-3BU (BU=BackUp), was prepared for another attempt. Pad crews hastened to repair the damage done to LC-18A by Vanguard TV-3's explosion, and in the third week of January 1958, the job was completed. Vanguard TV-3BU was erected on the pad, but continuous delays frustrated the launch attempt. Heavy rains shorted some electrical cables on the ground and necessitated their replacement. The second stage had also been sitting on the pad with a full load of nitric acid for several weeks, which eventually corroded the fuel tank and valves. It had to be removed and replaced by a different stage. Finally, the launch got under way on the night of 5 February 1958. The Vanguard lifted smoothly into the sky and performed well until 57 seconds into launch, when the booster pitched over almost 40°. The skinny second stage broke in half from aerodynamic stress four seconds later, causing the Vanguard to tumble end-over-end before range safety officer sent the destruct command. Cause of the failure was attributed to a spurious guidance signal that caused the first stage to perform unintended pitch maneuvers. The guidance system was modified to have greater redundancy, and efforts were made to improve quality control. On 17 March 1958, Vanguard TV-4 finally succeeded in orbiting the Vanguard 1 satellite. By that time, however, the Army's Juno (Jupiter-C) had already launched the United States' first satellite, Explorer 1. The Vanguard TV-4 rocket had put the satellite Vanguard 1, to a relatively high orbit of (3,966 by 653 kilometres (2,464 mi × 406 mi)). Vanguard 1 and its third stage remain in orbit as the oldest man-made artifacts in space.[18][19] The following four flights, TV-5 and SLV (Satellite Launch Vehicle) Vanguard SLV-1, Vanguard SLV-2 and Vanguard SLV-3 all failed, but on 17 February 1959, Vanguard SLV-4 launched Vanguard 2, weighing 10.8 kilograms (24 lb), into orbit. The SLVs were the "production" Vanguard rockets. Vanguard SLV-5 and Vanguard SLV-6 also failed, but the final flight on 18 September 1959, successfully orbited the 24 kilograms (53 lb) Vanguard 3 satellite. That last mission was designated Vanguard TV-4BU, because it used a remaining test vehicle, which had been upgraded with a new third stage, the Allegany Ballistics Laboratory X-248A2 Altair. This more powerful motor enabled the launch of the heavier payload. The combination of the AJ10 liquid engine and X-248 solid motor was also used, under the name Able, as an upper stage combination for Thor and Atlas space launch vehicles.

Launches

Vanguard launched 3 satellites out of 11 launch attempts:

- Vanguard TV3 - December 6, 1957 - Failed to orbit 1.36 kg (3 lb) satellite

- Vanguard TV3 Backup - February 5, 1958 - Failed to orbit 1.36 kg (3 lb) satellite

- Vanguard 1 (Vanguard TV4) - March 17, 1958 - Orbited 1.47 kg (3.25 lb) satellite

- Vanguard TV5 - April 28, 1958 - Failed to orbit 10.0 kg (22 lb) satellite

- Vanguard SLV-1 - May 27, 1958 - Failed to orbit 10.0 kg (22 lb) satellite

- Vanguard SLV-2 - June 26, 1958 - Failed to orbit 10.0 kg (22 lb) satellite

- Vanguard SLV-3 - September 26, 1958 - Failed to orbit 10.0 kg (22 lb) satellite

- Vanguard 2 (Vanguard SLV-4) - February 17, 1959 - Orbited 9.8 kg (21.6 lb) satellite

- Vanguard SLV-5 - April 13, 1959 - Failed to orbit 10.3 kg (22.7 lb) satellite

- Vanguard SLV-6 - June 22, 1959 - Failed to orbit 10.3 kg (22.7 lb) satellite

- Vanguard 3 (Vanguard TV4-BU, also Vanguard SLV-7) - September 18, 1959 - Orbited 22.7 kg (50 lb) satellite[20]

Specifications

- Stage Number: 1 - Vanguard

- Mass: 7,704 kg

- Empty Mass: 811 kg

- Thrust (vac): 134.7 kN

- Isp (sea level): 248 s (2.43 km/s)

- Burn time: 145 s

- Diameter: 1.14 m

- Length: 12.20 m

- Propellants: LOX/Kerosene

- Engines: General Electric X-405

- Stage Number: 2 - Delta A

- Mass: 2,164 kg

- Empty Mass: 694 kg

- Thrust (vac): 33.8 kN

- Isp: 271 seconds (2.66 km/s)

- Burn time: 115 s

- Diameter: 0.84 m

- Length: 5.36 m

- Propellants: Nitric acid/UDMH

- Engines: Aerojet AJ10-37

- Stage Number: 3 - Vanguard 3

- Mass: 210 kg

- Empty Mass: 31 kg

- Thrust (vac): 11.6 kN

- Isp: 230 seconds (2.3 km/s)

- Burn time: 31 s

- Isp (sea level): 210 seconds (2.1 km/s)

- Diameter: 0.50 m

- Length: 2.00 m

- Propellants: Solid

- Engines: Grand Central 33KS2800

See also

References

- "The Vanguard Satellite Launching Vehicle — An Engineering Summary". B. Klawans. April 1960, 212 pages. Martin Company Engineering Report No 11022, PDF of an optical copy.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - McDougall, Walter A. (1985). The Heavens and the Earth A Political History of the Space Age. New York: Basic Books. pp. 121. ISBN 0-465-02887-X.

- Stehling, Kurt R. (1961). Project Vanguard. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. p. 50.

- Correll, John T. "How the Air Force Got the ICBM" Air Force, July 2005.

- Willette, Lt Col (17 March 1951). "Research and Development on Proposed Rand Satellite Reconnaissance". United States Air Force Directorate of Intelligence. Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- "Chronology of Air Force Space Activities" (PDF). National Reconnaissance Office. p. 2. Retrieved 2016-02-27.

- Sheehan, Neil (2009). A Fiery Peace in a Cold War. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 299. ISBN 978-0-679-74549-5.

- McDougall, Walter A. (1985). The Heavens and the Earth A Political History of the Space Age. New York: Basic Books. pp. 122. ISBN 0-465-02887-X.

- Green, Constance; Lomask, Milton (1970). Vanguard a History. Washington D.C.: NASA. p. 41.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Drew Pearson, "USA Second Class Power?", Simon & Schuster, 1958

- McDougall, Walter A., (1985) ...the Heavens and the Earth

- Hearst Magazines (June 1956). "Satellite Rocket Will Resemble Shell". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. p. 70.

- Wade, Mark. "Encyclopedia Astronautica J". Retrieved 2016-02-28.

- History of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines by George P. Sutton, pp. 375-376, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Reston, VA, 2006 ISBN 1-56347-649-5

- Foerstner, Abigail (2007), James Van Allen: the first eight billion miles (illustrated, revised ed.), University of Iowa Press, p. 146, ISBN 978-0-87745-999-6, retrieved June 27, 2011

- Stehling, Kurt (1961) Project Vanguard

- "VANGUARD'S AFTERMATH: JEERS AND TEARS". Time. December 16, 1957. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

Scripps-Howard's WASHINGTON DAILY NEWS: SAMNIK IS KAPUTNIK

- "Vanguard 1 - Satellite Information". Satellite database. Heavens-Above. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- "Vanguard 1 Rocket - Satellite Information". Satellite database. Heavens-Above. Retrieved 2018-01-13.

- "Vanguard". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Mark Wade. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

Further reading

- Green, Constance, and Lomask, Milon, “Vanguard A History,” SP-4202, National Aeronautics And Space Administration,Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., 1970

- Foerstner, Abigail M., “James Van Allen: The First Eight Billion Miles ,” University of Iowa Press, Iowa City, Iowa, ISBN 978-0877459996, 2007

- McDougall, Walter A., “..the Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age,” Basic Books, New York, ISBN 978-1597401654, 1985

- Sheehan, Neil., “A Fiery Peace in a Cold War,” Vintage Books, New York, ISBN 978-0-679-74549-5, 2009

- Stehling, Kurt r., “Project Vanguard,” Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, New York, Library of CongressCatalog Card Number 61-8906, 1961

- Sutton, George P., “History of Liquid Propellant Rocket Engines,” American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Reston, VA, ISBN 1-56347-649-5, 2006

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |