Super heavy-lift launch vehicle

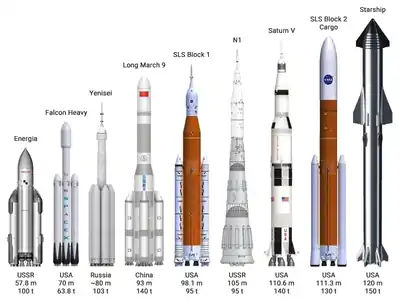

A super heavy-lift launch vehicle (SHLLV) is a launch vehicle capable of lifting more than 50 tonnes (110,000 lb) of payload into low Earth orbit (LEO).[1][2]

Flown vehicles

Retired

- Saturn V, with an Apollo program payload of a command module, service module, and Lunar Module. The three had a total mass of 45 t (99,000 lb).[3][4] When the third stage and Earth-orbit departure fuel was included, Saturn V actually placed 140 t (310,000 lb) into low Earth orbit.[5] The final launch of Saturn V placed Skylab, a 77,111 kg (170,001 lb) payload, into LEO.

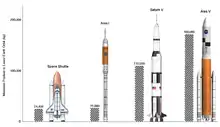

- The Space Shuttle orbited a combined[lower-alpha 1] shuttle and cargo mass of 122,534 kg (270,142 lb) when launching the Chandra X-ray Observatory on STS-93.[6] Chandra and its two-stage Inertial Upper Stage booster rocket weighed 22,753 kg (50,162 lb).[7]

- The Energia system was designed to launch up to 105 t (231,000 lb) to low Earth orbit.[8] Energia launched twice before the program was cancelled, but only one flight reached orbit. On the first flight, launching the Polyus weapons platform (approximately 80 t (180,000 lb)), the vehicle failed to enter orbit due to a software error on the kick-stage.[8] The second flight successfully launched the Buran orbiter.[9]

The Space Shuttle differed from traditional rockets in that the orbiter was essentially a reusable stage that carried cargo internally. Buran was also a reusable spaceplane but not a rocket "stage" as it had no rocket engine (except for on-orbit maneuvering). It relied entirely on the disposable launcher Energia to reach orbit.

Operational (unproven as super heavy-lift)

- Falcon Heavy is rated to launch 63.8 t (141,000 lb) to low Earth orbit (LEO) in a fully expendable configuration and an estimated 57 t (126,000 lb) in a partially reusable configuration, in which only two of its three boosters are recovered.[10][11][lower-alpha 2] As of September 2020 the latter configuration is planned to fly in early 2021, but with a much smaller payload being launched to geostationary orbit. The first test flight occurred on 6 February 2018, in a configuration in which recovery of all three boosters was attempted, with a small payload of 1,250 kg (2,760 lb) sent to an orbit beyond Mars.[13][14] A second and third flight have launched a 6,465 kg (14,253 lb)[15] and 3,700 kg (8,200 lb)[16] payload. Since the vehicle is operational but has not yet been demonstrated to launch payloads over 50 tonnes (110,000 lb) to orbit, it is as yet unproven as a super heavy-lift capable launch vehicle.

Suborbital tests

- N1, Soviet Moon rocket. Developed in late 1960s and early 1970s. Made 4 orbital launch attempts but did not reach orbit on any one of those flights. After the 4 failed launches, the project was cancelled in 1976.

- SpaceX Starship, US commercial private rocket in active development. Made first test flights in late 2019, with high-altitude test flights in 2020.

Comparison

| Rocket | Configuration | Organization | Nationality | LEO payload | Maiden flight | First >50t payload | Operational | Reusable | Launch Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturn V | Apollo | NASA | 140 t (310,000 lb)A | 1967 | 1967 | Retired | No | US$1.23 billion (2019) | |

| N1 | L3 | Energia | 95 t (209,000 lb) | 1969 (failed) | N/A | Cancelled | No | 3.0 billion rubles (1971) | |

| Space Shuttle | NASA | 27.5 t (61,000 lb)B | 1981 | 1981G | Retired | Partially | US$576 million (2012) to US$1.64 billion (2012) | ||

| Energia | Energia | 100 t (220,000 lb)C | 1987 | 1987 | Retired | No | US$764 million (1985) | ||

| Falcon Heavy | ExpendedD | SpaceX | 63.8 t (141,000 lb)[17] | Not YetD | Not Yet | UnprovenD | No | US$150 million (2018) | |

| Recoverable side boostersE | 57 t (126,000 lb)[10] | 2021 (planned)[18]D | Not Yet | UnprovenD | PartiallyE | US$130 million (2018) | |||

| Starship | SpaceX | 150 t (330,000 lb)[19]F | 2021 (planned)[20] | N/A | Development | Fully | US$2 million (2019) | ||

| SLS | Block 1 | NASA | 95 t (209,000 lb)[21] | 2021 (planned)[22] | N/A | Development | No | US$500 million (2019) to US$2 billion (2019) | |

| Block 1B | 105 t (231,000 lb)[23] | TBA | N/A | Development | No | Unknown | |||

| Block 2 | 130 t (290,000 lb)[24] | TBA | N/A | Development | No | Unknown | |||

| 921 rocket | CALT | 70 t (150,000 lb)[25] | TBA | N/A | Development | No | Unknown | ||

| Long March 9 | CALT | 140 t (310,000 lb)[26] | 2028 (planned)[27] | N/A | Development | No | Unknown | ||

| Yenisei | Yenisei | JSC SRC Progress | 103 t (227,000 lb) | 2028 (planned)[28] | N/A | Development | No | Unknown | |

| Don | 130 t (290,000 lb) | 2030 (planned) | N/A | Development | No | Unknown | |||

^A Includes mass of Apollo command and service modules, Apollo Lunar Module, Spacecraft/LM Adapter, Saturn V Instrument Unit, S-IVB stage, and propellant for translunar injection; payload mass to LEO is about 122.4 t (270,000 lb)[29]

^B Excludes mass of orbiter; Payload including orbiter during STS-93 is 122.5 t (270,000 lb)

^C Required upper stage or payload to perform final orbital insertion

^D Falcon Heavy has only flown in a fully recoverable configuration, which has a theoretical payload limit of around 45 tonnes; the first planned flight in a partially expendable configuration is planned for early 2021.

^E Side booster cores recoverable and centre core intentionally expended. First re-use of the side boosters was demonstrated in 2019 when the ones used on the Arabsat-6A launch were reused on the STP-2 launch.

^F Does not include dry mass of spaceship

^G Since payload mass of all flights includes mass of orbiter, the maiden flight had a greater than 50 tonne payload despite no deployable payload.

Proposed designs

The Space Launch System (SLS) is a US super heavy-lift expendable launch vehicle, which has been under development by NASA in a well-funded program for nearly a decade, and is currently slated to make its first flight in November 2021.[30] As of 2020, it is slated to be the primary launch vehicle for NASA's deep space exploration plans,[31][32] including the planned crewed lunar flights of the Artemis program and a possible follow-on human mission to Mars in the 2030s.[33][34][35]

The SpaceX Starship is both the second stage of a reusable launch vehicle and a spacecraft that is being developed by SpaceX, as a private spaceflight project.[36] It is being designed to be a long-duration cargo and passenger-carrying spacecraft.[37] While it will be tested on its own initially, it will be used on orbital launches with an additional booster stage, the Super Heavy, where Starship would serve as the second stage on a two-stage-to-orbit launch vehicle.[38] The combination of spacecraft and booster is called Starship as well.[39]

Long March 9, a 140 t (310,000 lb) to LEO capable rocket was proposed in 2018[40] by China, with plans to launch the rocket by 2028. The length of the Long March-9 will exceed 90 meters, and the rocket would have a core stage with a diameter of 10 meters. Long March 9 is expected to carry a payload of 140 tonnes into low-Earth orbit, with a capacity of 50 tonnes for Earth-Moon transfer orbit.[41]

Yenisei,[42] a super heavy-lift launch vehicle using existing components instead of pushing the less-powerful Angara A5V project, was proposed by Russia's RSC Energia in August 2016.[43] A revival of the Energia rocket was also proposed in 2016, also to avoid pushing the Angara project.[44] If developed, this vehicle could allow Russia to launch missions towards establishing a permanent Moon base with simpler logistics, launching just one or two 80-to-160-tonne super-heavy rockets instead of four 40-tonne Angara A5Vs implying quick-sequence launches and multiple in-orbit rendezvous. In February 2018, the КРК СТК (space rocket complex of the super-heavy class) design was updated to lift at least 90 tonnes to LEO and 20 tonnes to lunar polar orbit, and to be launched from Vostochny Cosmodrome.[45] The first flight is scheduled for 2028, with Moon landings starting in 2030.[28]

In India, there have been multiple mentions about concept of various heavy and super-heavy rocket designs and configurations, capable of putting 50 to 100 tonnes in LEO and 20 to 35 tonnes in GTO in various presentations from ISRO officials which were studied in 2000s and 2010s.,[46][47] mostly speculated to be a variant of Unified Launch Vehicle powered by clustered SCE-200 engines, currently under development.[48][49][50] ISRO has confirmed to be conducting preliminary research for the development of a super heavy-lift launch vehicle which is planned to have a lifting capacity of over 50-60 tonnes (presumably into LEO).[51]

Blue Origin has plans to build a larger rocket than their New Glenn currently under construction, termed New Armstrong.[52]

Cancelled designs

Numerous super-heavy lift vehicles have been proposed and received various levels of development prior to their cancellation.

As part of the Soviet Lunar Project four N1 rockets with a payload capacity of 95 t (209,000 lb), were launched but all failed shortly after lift-off (1969-1972).[53] The program was suspended in May 1974 and formally cancelled in March 1976.[54][55] The Soviet UR-700 rocket design concept was competed against the N1, however the UR-700 was never developed. In the concept, it was to have had a payload capacity of up to 151 t (333,000 lb)[56] to low earth orbit.

During project Aelita (1969-1972), the Soviets were developing a way to beat the Americans to Mars. They designed the UR-700m, a nuclear powered variant of the UR-700, to assemble the 1,400 t (3,100,000 lb) MK-700 spacecraft in earth orbit in two launches. The rocket would have a payload capacity of 750 t (1,650,000 lb) and is the most capable rocket ever designed. It is often overlooked due to little information being known about the design. The only Universal Rocket to make it past the design phase was the UR-500 while the N1 was selected to be the Soviets' HLV for lunar and Martian missions.[57]

The General Dynamics Nexus was proposed in the 1960s as a fully reusable successor to the Saturn V rocket, having the capacity of transporting up to 450–910 t (990,000–2,000,000 lb) to orbit.[58][59]

The UR-900, proposed in 1969, would have had a payload capacity of 240 t (530,000 lb) to low earth orbit. It never left the drawing board.[60]

The American Saturn MLV family of rockets was proposed in 1965 by NASA as successors to the Saturn V rocket.[61] It would have been able to carry up to 160.880 t (354,680 lb) to Low earth orbit. The Nova designs were also studied by NASA before the agency chose the Saturn V in the early 1960s.[62]

Based on the recommendations of the Stafford Synthesis report, First Lunar Outpost (FLO) would have relied on a massive Saturn-derived launch vehicle known as the Comet HLLV. The Comet would have been capable of injecting 230.8 t (508,800 lb) into low earth orbit and 88.5 t (195,200 lb) on a TLI making it one of the most capable vehicles ever designed.[63] FLO was cancelled during the design process along with the rest of the Space Exploration Initiative.

The U.S. Ares V for the Constellation program was intended to reuse many elements of the Space Shuttle program, both on the ground and flight hardware, to save costs. The Ares V was designed to carry 188 t (414,000 lb) and was cancelled in 2010.[64]

The Shuttle-Derived Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle ("HLV") was an alternate super heavy-lift launch vehicle proposal for the NASA Constellation program, proposed in 2009.[65]

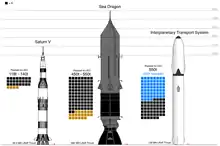

A 1962 design proposal, Sea Dragon, called for an enormous 150 m (490 ft) tall, sea-launched rocket capable of lifting 550 t (1,210,000 lb) to low Earth orbit. Although preliminary engineering of the design was done by TRW, the project never moved forward due to the closing of NASA's Future Projects Branch.[66][67]

The Rus-M was a proposed Russian family of launchers whose development began in 2009. It would have had two super heavy variants: one able to lift 50-60 tons, and another able to lift 130-150 tons.[68]

SpaceX Interplanetary Transport System was a 12 m (39 ft) diameter launch vehicle concept unveiled in 2016. The payload capability was to be 550 t (1,210,000 lb) in an expendable configuration or 300 t (660,000 lb) in a reusable configuration.[69] In 2017 the 12 m design was succeeded at SpaceX by a 9 m (30 ft) diameter concept Big Falcon Rocket which was renamed as SpaceX Starship.[70]

See also

- Comparison of orbital launch systems

- List of orbital launch systems

- Sounding rocket, suborbital launch vehicle

- Small-lift launch vehicle, capable of lifting up to 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) to low Earth orbit

- Medium-lift launch vehicle, capable of lifting 2,000 to 20,000 kg (4,400 to 44,000 lb) of payload into low Earth orbit

- Heavy-lift launch vehicle, capable of lifting 20,000 to 50,000 kg (44,000 to 110,000 lb) of payload into low Earth orbit

Notes

- The Space Shuttle orbiter is part of a stage of the launch vehicle (together with the Space Shuttle external tank), but is also itself a spacecraft capable of operating for extended periods with a crew in low Earth orbit. Whether the orbiter mass should be accounted as "payload", or the payload should be accounted as only the cargo and crew carried in the orbiter, may depend on the operational definition used, and hence is debatable. The validity of its inclusion on this page depends on this definition.

- A configuration in which all three cores are intended to be recoverable is classified as a heavy-lift launch vehicle since its maximum possible payload to LEO is under 50,000 kg.[12][11]

References

- McConnaughey, Paul K.; et al. (November 2010). "Draft Launch Propulsion Systems Roadmap: Technology Area 01" (PDF). NASA. Section 1.3.

Small: 0–2 t payloads; Medium: 2–20 t payloads; Heavy: 20–50 t payloads; Super Heavy: > 50 t payloads

- "Seeking a Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of a Great Nation" (PDF). Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee. NASA. October 2009. pp. 64–66.

...the U.S. human spaceflight program will require a heavy-lift launcher ... in the range of 25 to 40 mt ... this strongly favors a minimum heavy-lift capacity of roughly 50 mt....

- "Apollo 11 Lunar Module". NASA.

- "Apollo 11 Command and Service Module (CSM)". NASA.

- Alternatives for Future U.S. Space-Launch Capabilities (PDF), The Congress of the United States. Congressional Budget Office, October 2006, pp. X, 1, 4, 9

- "STS-93". Shuttlepresskit.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2000.

- "Heaviest payload launched - shuttle". Guinness World Records.

- "Polyus". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- "Buran". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (12 February 2018). "Side boosters landing on droneships & center expended is only ~10% performance penalty vs fully expended. Cost is only slightly higher than an expended F9, so around $95M" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Capabilities & Services". SpaceX. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (30 April 2016). "@elonmusk Max performance numbers are for expendable launches. Subtract 30% to 40% for reusable booster payload" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Chang, Kenneth (6 February 2018). "Falcon Heavy, SpaceX's Big New Rocket, Succeeds in Its First Test Launch". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- "Tesla Roadster (AKA: Starman, 2018-017A)". ssd.jpl.nasa.gov. 1 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Arabsat 6A". Gunter's Space Page. Archived from the original on 16 July 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- SMC [@AF_SMC] (18 June 2019). "The 3700 kg Integrated Payload Stack (IPS) for #STP2 has been completed! Have a look before it blasts off on the first #DoD Falcon Heavy launch! #SMC #SpaceStartsHere" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Falcon Heavy". SpaceX. 16 November 2012. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- Clark, Stephen. "Falcon Heavy set for design validation milestone before late 2020 launch". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Elon Musk [@elonmusk] (23 May 2019). "Aiming for 150 tons useful load in fully reusable configuration, but should be at least 100 tons, allowing for mass growth" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- "Starship's first flight in low-Earth orbit will take place in 2021 – Space". En24 News. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- Harbaugh, Jennifer, ed. (9 July 2018). "The Great Escape: SLS Provides Power for Missions to the Moon". NASA. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Gebhardt, Chris (21 February 2020). "SLS debut slips to April 2021, KSC teams working through launch sims". nasaspaceflight.com. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- "Space Launch System" (PDF). NASA Facts. NASA. 11 October 2017. FS-2017-09-92-MSFC. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Creech, Stephen (April 2014). "NASA's Space Launch System: A Capability for Deep Space Exploration" (PDF). NASA. p. 2. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- https://www.space.com/china-rocket-for-crewed-moon-missions

- Mizokami, Kyle (20 March 2018). "China Working on a New Heavy-Lift Rocket as Powerful as Saturn V". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- Wong, Brian (20 September 2018). "Long March 9 will take 140 tons to low-earth orbit starting 2028". Next Big Future. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- Zak, Anatoly (8 February 2019). "Russia Is Now Working on a Super Heavy Rocket of Its Own". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- https://www.space.com/33691-space-launch-system-most-powerful-rocket.html

- Clark, Stephen (1 May 2020). "Hopeful for launch next year, NASA aims to resume SLS operations within weeks". Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Siceloff, Steven (12 April 2015). "SLS Carries Deep Space Potential". Nasa.gov. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- "World's Most Powerful Deep Space Rocket Set To Launch In 2018". Iflscience.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Chiles, James R. "Bigger Than Saturn, Bound for Deep Space". Airspacemag.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- "Finally, some details about how NASA actually plans to get to Mars". Arstechnica.com. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- Gebhardt, Chris (6 April 2017). "NASA finally sets goals, missions for SLS – eyes multi-step plan to Mars". NASASpaceFlight.com. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- Berger, Eric (29 September 2019). "Elon Musk, Man of Steel, reveals his stainless Starship". Ars Technica. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- Lawler, Richard (20 November 2018). "SpaceX BFR has a new name: Starship". Engadget. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Boyle, Alan (19 November 2018). "Goodbye, BFR … hello, Starship: Elon Musk gives a classic name to his Mars spaceship". GeekWire. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

Starship is the spaceship/upper stage & Super Heavy is the rocket booster needed to escape Earth’s deep gravity well (not needed for other planets or moons)

- "Starship". SpaceX. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- https://spacenews.com/china-reveals-details-for-super-heavy-lift-long-march-9-and-reusable-long-march-8-rockets/

- Mu Xuequan (19 September 2018). "China to launch Long March-9 rocket in 2028". Xinhua.

- Zak, Anatoly (19 February 2019). "The Yenisei super-heavy rocket". RussianSpaceWeb. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- ""Роскосмос" создаст новую сверхтяжелую ракету". Izvestia (in Russian). 22 August 2016.

- "Роскосмос" создаст новую сверхтяжелую ракету. Izvestia (in Russian). 22 August 2016.

- "РКК "Энергия" стала головным разработчиком сверхтяжелой ракеты-носителя" [RSC Energia is the lead developer of the super-heavy carrier rocket]. RIA.ru. RIA Novosti. 2 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Indian Moon Rockets: First Look". 25 February 2010. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020 – via SuperNova - Indian Space Web.

- Somanath, S. (3 August 2020). Indian Innovations in Space Technology: Achievements and Aspirations (Speech). VSSC. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020 – via imgur.

- Brügge, Norbert. "ULV (LMV3-SC)". B14643.de. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- Brügge, Norbert. "Propulsion ULV". B14643.de. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- Brügge, Norbert. "LVM3, ULV & HLV". B14643.de. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- "Have tech to configure launch vehicle that can carry 50-tonne payload: Isro chairman - Times of India". The Times of India. 14 February 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- https://www.cnet.com/news/blue-origins-huge-new-rocket-has-a-nose-cone-bigger-than-its-current-rocket/

- "N1 Moon Rocket". Russianspaceweb.com.

- Harvey, Brian (2007). Soviet and Russian Lunar Exploration. Springer-Praxis Books in Space Exploration. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-387-21896-0.

- van Pelt, Michel (2017). Dream Missions: Space Colonies, Nuclear Spacecraft and Other Possibilities. Springer-Praxis Books in Space Exploration. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 22. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-53941-6. ISBN 978-3-319-53939-3.

- http://www.astronautix.com/u/ur-700.html

- "UR-700M". www.astronautix.com. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4221/ch2.htm

- http://www.astronautix.com/n/nexus.html

- http://www.astronautix.com/u/ur-900.html

- https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19650020081_1965020081.pdf

- https://astronomy.com/news/2019/05/nova-the-apollo-rocket-that-never-was

- http://www.astronautix.com/f/firstlunaroutpost.html

- http://www.astronautix.com/a/ares.html

- https://www.nasa.gov/pdf/361842main_15%20-%20Augustine%20Sidemount%20Final.pdf

- Grossman, David (3 April 2017). "The Enormous Sea-Launched Rocket That Never Flew". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- “Study of Large Sea-Launch Space Vehicle,” Contract NAS8-2599, Space Technology Laboratories, Inc./Aerojet General Corporation Report #8659-6058-RU-000, Vol. 1 – Design, January 1963

- http://www.russianspaceweb.com/ppts_lv.html

- "Making Humans a Multiplanetary Species" (PDF). SpaceX. 27 September 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- Boyle, Alan (19 November 2018). "Goodbye, BFR … hello, Starship: Elon Musk gives a classic name to his Mars spaceship". GeekWire. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

.jpg.webp)