Wind power in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom is one of the best locations for wind power in the world and is considered to be the best in Europe.[2][3] Wind power contributed 20% of UK electricity generation in 2019, making up 54% of electricity generation from renewable sources.[4] Polling of public opinion consistently shows strong support for wind power in the UK, with nearly three quarters of the population agreeing with its use, even for people living near onshore wind turbines.[5][6][7][8][9][10] Wind power in the UK is a low cost generation mode which is still dropping in price and delivers a rapidly growing percentage of the electricity of the United Kingdom.

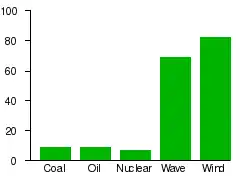

UK Net generated electricity in 2019 (i.e. excluding imports)[1]

By the beginning of December 2020, wind power production consisted of 10,930 wind turbines with a total installed capacity of over 24.1 gigawatts: 13.7 gigawatts of onshore capacity and 10.4 gigawatts of offshore capacity.[11] This placed the United Kingdom at this time as the world's sixth largest producer of wind power.[12] The UK Government has committed to 40 GW of installed offshore capacity by 2030,[13] bringing overall UK wind capacity to over 50 GW (c.f. the UK's electricity demand of between ~30 and ~45 GW in 2019.)[14] In October 2020, the UK government set a new target for floating offshore wind to generate 1 GW by 2030.[15]

Through the Renewables Obligation, British electricity suppliers are now required by law to provide a proportion of their sales from renewable sources such as wind power or pay a penalty fee. The supplier then receives a Renewables Obligation Certificate (ROC) for each MW·h of electricity they have purchased.[16] Within the United Kingdom wind power is the largest source of renewable electricity.[17]

Historically, wind power has raised costs of electricity slightly. In 2015, it was estimated that the use of wind power in the UK had added £18 to the average yearly electricity bill.[18] This was the additional cost to consumers of using wind to generate about 9.3% of the annual total (see table below) – about £2 for each 1%. Offshore wind power has been significantly more expensive than onshore, which raised costs. Offshore wind projects completed in 2012–14 had a levelised cost of electricity of £131/MWh compared to a wholesale price of £40–50/MWh.[19] In 2016, wind power first surpassed coal in UK electricity generation,[20][21] and in the first quarter of 2018 surpassed nuclear power generation for the first time.[22] In 2016 it was predicted that onshore wind power would have the lowest levelised cost of electricity in the United Kingdom in 2020 when a carbon cost was applied to generating technologies.[23]:p25 However, in 2019, a strike price was agreed during the latest CfD round for £39.65/MWh for Offshore wind projects which is lower than the expected UK wholesale electricity price even without carbon pricing, meaning that this will be the first "negative subsidy" wind farm operating in the UK. In 2017 the Financial Times reported that new offshore wind costs had fallen by nearly a third over four years, to an average of £97/MWh, meeting the government's £100/MWh target four years early.[24] Later in 2017 two offshore wind farm bids were made at a cost of £57.50/MWh for construction by 2022–23. In the 2019 Contracts for Difference round, about 6GW of clean energy is to be added to the grid by 2025 at around £47/MWh at 2019 prices; the first round that prices were lower than current generation costs.[25][26]

| Year[27] | Capacity (MW) |

Generation (GW·h) |

Capacity factor |

% of total electricity use |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2,974 | 5,357 | 20.6% | 1.50 | [28] |

| 2009 | 4,051 | 6,904 | 19.5% | 2.01 | [28] |

| 2010 | 5,204 | 7,950 | 17.4% | 2.28 | [28] |

| 2011 | 6,540 | 12,675 | 22.1% | 3.81 | |

| 2012 | 8,871 | 20,710 | 26.7% | 5.52 | |

| 2013 | 10,976 | 24,500 | 25.5% | 7.39 | [29] |

| 2014 | 12,440 | 28,100 | 25.8% | 9.30 | [30] |

| 2015 | 13,602 | 40,442 | 33.9% | 11.0 | [31] |

| 2016 | 16,218 | 37,368 | 26.3% | 12 | [32] |

| 2017 | 19,837 | 49,607 | 28.5% | 17 | [32][33] |

| 2018 | 21,700 | 57,100 | 30.0% | 18 | [34][35] |

| 2019 | 23,950 | 64,134 | 32% | 21% | [36][4] |

History

The world's first electricity generating wind turbine was a battery charging machine installed in July 1887 by Scottish academic James Blyth to light his holiday home in Marykirk, Scotland.[37] It was in 1951 that the first utility grid-connected wind turbine to operate in the United Kingdom was built by John Brown & Company in the Orkney Islands.[37][38] In the 1970s, industrial scale wind generation was first proposed as an electricity source for the United Kingdom; the higher working potential of offshore wind was recognised with a capital cost per kilowatt estimated at £150 to £250.[39]

In 2007 the United Kingdom Government agreed to an overall European Union target of generating 20% of the EU's energy supply from renewable sources by 2020. Each EU member state was given its own allocated target: for the United Kingdom it is 15%. This was formalised in January 2009 with the passage of the EU Renewables Directive. As renewable heat and renewable fuel production in the United Kingdom are at extremely low bases, RenewableUK estimated that this would require 35–40% of the United Kingdom's electricity to be generated from renewable sources by that date,[40] to be met largely by 33–35 gigawatts (GW) of installed wind capacity.

In December 2007, the Government announced plans for an expansion of wind energy in the United Kingdom, by conducting a Strategic Environmental Assessment of up to 25 GW worth of wind farm offshore sites in preparation for a new round of development. These proposed sites were in addition to the 8 GW worth of sites already awarded in the 2 earlier rounds of site allocations, Round 1 in 2001 and Round 2 in 2003. Taken together it was estimated that this would result in the construction of over 7,000 offshore wind turbines.[41]

In 2010, 653 MW of offshore wind came online. The following year, only one offshore wind farm, phase 1 of the Walney Wind Farm, was completed in 2011 with a capacity of 183 MW. On 28 December 2011 wind power set a then record contribution to the United Kingdom's demand for electricity of 12.2%.[42]

2012 was a significant year for the offshore wind industry with 4 large wind farms becoming operational with over 1.1 GW of generating capability coming on stream.[43] In the year July 2012 to June 2013, offshore wind farms with a capacity of 1,463 MW were installed, for the first time growing faster than onshore wind which grew by 1,258 MW.[44] The offshore wind industry continued to develop in 2013 with what was once the largest wind farm in the world, the London Array, becoming operational with over 630 MW of generating capability coming on stream.[45]

During 2013, 27.4 TW·h of energy was generated by wind power, which contributed 8.7% of the UK's electricity requirement.[46]

On 1 August 2013 Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg opened the Lincs Offshore Wind Farm. On commissioning the total capacity of wind power exceeded 10GW of installed capacity.

During 2014, 28.1 TW·h of energy was generated by wind power (an average of 3.2 GW, about 24% of the 13.5 GW installed capacity at the time), which contributed 9.3% of the UK's electricity requirement.[47] In the same year, Siemens announced plans to build a £310 million ($264 million) facility for making offshore wind turbines in Paull, England, as Britain's wind power capacity rapidly expands. Siemens chose the Hull area on the east coast of England because it is close to other large offshore projects planned in coming years. The new plant began producing turbine rotor blades in December 2016.[48] The plant and the associated service centre, in Green Port Hull nearby, will employ about 1,000 workers.[49]

During 2015, 40.4 TW·h of energy was generated by wind power and the quarterly generation record was set in the three-month period from October to December 2015, with 13% of the nation's electricity demand met by wind.[50] 2015 saw 1.2 GW of new wind power capacity brought online, a 9.6% increase of the total UK installed capacity. Three large offshore wind farms came on stream in 2015, Gwynt y Môr (576 MW max. capacity), Humber Gateway (219 MW) and Westermost Rough (210 MW).

In 2016, the chief executive of DONG Energy (now known as Ørsted A/S), the UK's largest windfarm operator, predicted that wind power could supply more than half of the UK's electricity demand in future. He pointed to the tumbling cost of green energy as evidence that wind and solar could supplant fossil fuels quicker than expected.[51]

Wind farms

Offshore

The total offshore wind power capacity installed in the United Kingdom as of February 2019 is 8,483 MW, the largest in the world. The United Kingdom became the world leader of offshore wind power generation in October 2008 when it overtook Denmark.[52] In 2013 the 175-turbine London Array wind farm, located off the Kent coast, became the largest offshore wind farm in the world; this was surpassed in 2018 by the Walney 3 Extension.

The United Kingdom has been estimated to have over a third of Europe's total offshore wind resource, which is equivalent to three times the electricity needs of the nation at current rates of electricity consumption[53] (In 2010 peak winter demand was 59.3 GW,[54] in summer it drops to about 45 GW). One estimate calculates that wind turbines in one third of United Kingdom waters shallower than 25 metres (82 ft) would, on average, generate 40 GW; turbines in one third of the waters between 25 metres (82 ft) and 50 metres (164 ft) depth would on average generate a further 80 GW, i.e. 120 GW in total.[55] An estimate of the theoretical maximum potential of the United Kingdom's offshore wind resource in all waters to 700 metres (2,300 ft) depth gives the average power as 2200 GW.[56]

The first developments in United Kingdom offshore wind power came about through the now discontinued Non-Fossil Fuel Obligation (NFFO), leading to two wind farms, Blyth Offshore and Gunfleet sands.[57] The NFFO was introduced as part of the Electricity Act 1989 and obliged United Kingdom electricity supply companies to secure specified amounts of electricity from non-fossil sources,[58] which provided the initial spur for the commercial development of renewable energy in the United Kingdom.

Offshore wind projects completed in 2010–11 had a levelised cost of electricity of £136/MWh, which fell to £131/MWh for projects completed in 2012–14 and £121/MWh for projects approved in 2012–14; the industry hopes to get the cost down to £100/MWh for projects approved in 2020.[19] The construction price for offshore windfarms has fallen by almost a third since 2012 while technology improved and developers think a new generation of even larger turbines will enable yet more future cost reductions.[59] In 2017 the UK built 53% of the 3.15GW European offshore wind farm capacity.[60] In 2020, Boris Johnson pledged that, by the end of the decade, offshore wind would generate enough energy to power every UK home.[61]

Round 1

In 1998 the British Wind Energy Association (now RenewableUK) began discussions with the government to draw up formal procedures for negotiating with the Crown Estate, the owner of almost all the United Kingdom coastline out to a distance of 12 nautical miles (22.2 km), to build offshore wind farms. The result was a set of guidelines published in 1999, to build "development" farms designed to give developers a chance to gain technical and environmental experience. The projects were limited to 10 square kilometres in size and with a maximum of 30 turbines. Locations were chosen by potential developers and a large number of applications were submitted. Seventeen of the applications were granted permission to proceed in April 2001, in what has become known as Round 1 of United Kingdom offshore wind development.[62]

The first of the Round 1 projects was North Hoyle Wind Farm, completed in December 2003. The final project, Teesside, was completed in August 2013. Twelve Round 1 farms in total are in operation providing a maximum power generating capacity of 1.2 GW. Five sites were withdrawn, including the Shell Flat site off the coast of Lancashire.[63]

Round 2

Lessons learnt from Round 1, particularly the difficulty in getting planning consent for offshore wind farms, together with the increasing pressure to reduce CO2 emissions, prompted the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) to develop a strategic framework for the offshore wind industry. This identified three restricted areas for larger scale development, Liverpool Bay, the Thames Estuary and the area beyond the Wash, called the Greater Wash, in the North Sea. Development was prevented in an exclusion zone between 8 and 13 km offshore to reduce visual impact and avoid shallow feeding grounds for sea birds. The new areas were tendered to prospective developers in a competitive bid process known as Round 2. The results were announced in December 2003 with 15 projects awarded with a combined power generating capacity of 7.2 GW. By far the largest of these is the 900 MW Triton Knoll.[65] As before a full Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) would be needed along with an application for planning consent.

The first of the Round 2 projects was Gunfleet Sands II, completed in April 2010 and six others are now operational including the London Array, formerly the largest wind farm in the world. Four other Round 2 sites are currently under construction.[63]

Round 1 and 2 Extensions

In May 2010 the Crown Estate gave approval for seven Round 1 and 2 sites to be extended creating an additional 2 GW of offshore wind capacity.[66] Each wind farm extension will require a complete new planning application including an Environmental Impact Assessment and full consultation. The sites are:[67]

- Burbo Bank and Walney: DONG Energy UK.

- Kentish Flats and Thanet: Vattenfall.

- Greater Gabbard: SSE Renewables and RWE Npower Renewables.

- Race Bank: Centrica Renewable Energy.

- Dudgeon: Statoil and Statkraft.

Round 3

Following on from the Offshore wind SEA announced by the Government in December 2007, the Crown Estate launched a third round of site allocations in June 2008. Following the success of Rounds 1 and 2, and important lessons were learnt - Round 3 was on a much bigger scale than either of its predecessors combined (Rounds 1 and 2 allocated 8 GW of sites, while Round 3 alone could identify up to 25 GW).

The Crown Estate proposed 9 offshore zones, within which a number of individual wind farms would be situated. It ran a competitive tender process to award leases to consortia of potential developers. The bidding closed in March 2009 with over 40 applications from companies and consortia and multiple tenders for each zone. On 8 January 2010 the successful bidders were announced.

Following the allocation of zones, individual planning applications still have to be sought by developers. These are unlikely to be completed before 2012 and as such the first Round 3 projects are not expected to begin generating electricity before 2015.

Round 3 consortia

During the bidding process, there was considerable speculation over which companies had bid for the zones. The Crown Estate did not make the list public and most of the consortia also remained silent. The successful bidders for each zone were eventually announced as follows:[68]

| Zone[69] | Zone name | Wind farm site names | Potential power (GW) | Developer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Moray Firth | Beatrice | 1.3 (0.58) | Moray Offshore Renewables Ltd | formed from EDP Renováveis and SeaEnergy Renewables Ltd (SERL)

Project scaled down to 588MW Commenced commercial operation in 2018 |

| 2 | Firth of Forth | Alpha/Bravo | 3.5 | Seagreen Wind Energy Ltd | partnership between SSE Renewables and Fluor Ltd. SSE withdrawing support beyond the consent process. |

| 3 | Dogger Bank | Crekye A/B & Teesside A/B/C/D | 7.2 | Forewind Ltd | a consortium made up of SSE Renewables, RWE npower, Statkraft and Statoil. SSE withdrawing support beyond the consent process. Project scaled down to 4.8GW IN 2015 Expected to commence commercial operation in 2024 |

| 4 | Hornsea | Hornsea One, Two, Three and Four (formerly Heron/Njord/Breesea/Optimus & SPC5/6/7/8) | 6 | Ørsted (formerly SMart Wind Ltd) | SMart Wind was a joint venture between Mainstream Renewable Power and Siemens Project Ventures. 100% acquired in 2015 by DONG Energy, which rebranded as Ørsted in 2017.

Hornsea One (1.2GW) became fully operational in December 2019.[70] Hornsea Two (1.4GW) is under construction as of January 2021. Development consent for Hornsea Three (2.4GW) was granted on 31 December 2020.[71] Hornsea Four remains in development. |

| 5 | East Anglia | East Anglia ONE/THREE/FOUR | 7.2 | East Anglia Offshore Wind Limited | joint venture between ScottishPower Renewables and Vattenfall AB

ONE commenced commercial operations in 2020 TWO is expected to be fully operational by 2022 THREE is expected to start construction in 2022 |

| 6 | Southern Array | Rampion | 0.6 (0.4) | E.ON Climate & Renewables / UK Southern Array Ltd | located south of Shoreham-by-Sea and Worthing in the English Channel

Commenced commercial operation in 2018 |

| 7 | West of Isle of Wight | Navitus Bay | 0.9 | Eneco Round 3 Development Ltd | west of the Isle of Wight; partnership between Eneco and EDF. Planning permission refused by government in September 2015 due to visual impact.[72] |

| 8 | Atlantic Array | Atlantic Array | Channel Energy Ltd (Innogy) | Withdrawn in November 2013 as "project uneconomic at current time" [73] | |

| 9 | Irish Sea | Celtic Array | Celtic Array Limited | Withdrawn in July 2014 due to "challenging ground conditions that make the project economically unviable".[74] | |

| Total | 26.7 |

In 2009, during the Round 3 initial proposal stage 26.7GW of potential capacity was planned. However, due to government planning permission refusal, challenging ground conditions and project financing issues a number of proposed sites were withdrawn. A number of other sites were also reduced in scope.

Round 4

Round 4 was announced in 2019 and represented the first large scale new leasing round in a decade. This offers the opportunity for up to 7GW of new offshore capacity to be developed in the waters around England in Wales.[75] This is split into four bidding areas:

- Dogger Bank

- Eastern Regions

- South East

- Northern Wales and Irish Sea

The tenders are under review and the Agreements for Lease will be announced in Autumn 2021.

Future plans

The UK has accelerated its decommissioning of coal power stations aiming for a 2024 phase-out date,[76] and recent European Nuclear power stations have encountered significant technical issues and project overruns that have resulted in significant increases in project costs.[77] These issues have resulted in new UK Nuclear projects failing to secure project financing. Similarly, SMR technology is not currently economically competitive with offshore wind in the UK. Following the Fukushima nuclear disaster public support for new nuclear has fallen.[78] In response, the UK government increased its previous commitment for 40 GW of Offshore wind capacity by 2030.[79] As of 2020, this represents a 355% increase over current capacity in 10 years. It is expected the Crown Estate will announce multiple new leasing Rounds and increases to existing bidding areas throughout the 2020-2030 period to achieve the governments aim of 40 GW.

Scottish offshore

In addition to the 25 GW scoped under the Round 3 SEA, the Scottish Government and the Crown Estate also called for bids on potential sites within Scottish territorial waters. These were originally considered as too deep to provide viable sites, but 17 companies submitted tenders and the Crown Estate initially signed exclusivity agreements with 9 companies for 6 GW worth of sites. Following publication of the Scottish Government's sectoral marine plan for offshore wind energy in Scottish territorial waters in March 2010,[80] six sites were given approval subject to securing detailed consent. Subsequently, 4 sites have been granted agreements for lease.[81]

The complete list of sites including power updates and developer name changes:

| Site Name | Potential power (MW) | Developer | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beatrice | 588 | SSE Renewables plc and Talisman Energy | SSE owns 40%, Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP) (35%) and SDIC Power (25%). Application approved by Marine Scotland in March 2014, Construction to begin early 2017.[82] Fully operational in June 2019 [83] | |

| Inch Cape | 1000 | Repsol Nuevas Energias SA EDP Renewables | Repsol owns 51%, EDPR owns 49%. Application approved by Marine Scotland in October 2014 | |

| Neart Na Gaoithe | 450 | Mainstream Renewable Power Ltd | Application approved by Marine Scotland in October 2014 | |

| Islay | SSE Renewables | No further investment from SSE into the project for the foreseeable future.[84] | ||

| Solway Firth | E.ON Climate & Renewables UK Developments | Dormant – Unsuitable for development | ||

| Wigtown Bay | DONG Wind (UK) | Dormant – Unsuitable for development | ||

| Kintyre | Airtricity Holdings (UK) Ltd | Cancelled due to proximity to local communities and Campbeltown Airport[85] | ||

| Forth Array | Fred. Olsen Renewables Ltd | Cancelled. Fred. Olsen pulled out to concentrate on its onshore developments[86] | ||

| Bell Rock | Airtricity Holdings (UK) Ltd Fluor Ltd | Cancelled due to radar services in the area[87] | ||

| Argyll Array | Scottish Power Renewables | Cancelled due to ground conditions and presence of basking sharks[88] | ||

| Total | 2,200 |

List of operational and proposed offshore wind farms

| Farm | Commissioned | Estimated completion | Power (MW) | No. Turbines | Operator | Notes | Round |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Hoyle | December 2003 | 60 | 30 | Greencoat (formerly Npower Renewables) | United Kingdom's first major offshore wind farm. | 1 | |

| Scroby Sands | December 2004 | 60 | 30 | E.ON UK | 1 | ||

| Kentish Flats | December 2005 | 140 | 45 | Vattenfall | Extension added in 2015.[11] | 1 | |

| Barrow Offshore Wind | May 2006 | 90 | 30 | Ørsted | 1 | ||

| Burbo Bank | October 2007 | 348 | 57 | Ørsted | 258 MW, 32 turbine extension completed in April 2017.[90] | 1–2 | |

| Lynn and Inner Dowsing | October 2008 | 194 | 54 | Green Investment Bank | 1 | ||

| Rhyl Flats | December 2009 | 90 | 25 | RWE Npower | Officially inaugurated 2 December 2009[91] | 1 | |

| Gunfleet Sands | April 2010 | 173 | 48 | Ørsted | Officially inaugurated 15 June 2010[92] | 1–2 | |

| Robin Rigg | April 2010 | 174 | 60 | E.ON UK | 1 | ||

| Thanet | September 2010 | 300 | 100 | Vattenfall | 2 | ||

| Walney | February 2012[93] | 1,026 | 189 | Ørsted | Extended in September 2018 with a 659 MW, 87 turbine extension.[94] | 2 | |

| Ormonde | February 2012 | 150 | 30 | Vattenfall | Commissioned 22 February 2012.[95] | 1 | |

| Greater Gabbard | August 2012 | 857 | 196 | Airtricity and Fluor Ltd | Commissioned 7 August 2012.[96] 56 turbine, 353 MW extension "Galloper" completed in April 2018.[97] | 2 | |

| Sheringham Shoal | September 2012 | 317 | 88 | Vattenfall | Commissioned 27 September 2012[98] | 2 | |

| London Array | April 2013 [99] | 630 | 175 | Siemens Gamesa | Commissioned 6 April 2013.[100] Was world's largest offshore wind farm until 2018.[101] Phase 2 (370MW) scrapped.[102] | 2 | |

| Lincs | July 2013 | 270 | 75 | Green Investment Bank | Commissioned 5 July 2013 [103] | 2 | |

| Teesside | August 2013 | 62 | 27 | EDF Energy | Final Round 1 project completed | 1 | |

| Fife Energy Park (Methil) | October 2013 | 7 | 1 | Catapult | 7MW turbine evaluation project. Installation complete March 2014[104] | Demo | |

| West of Duddon Sands | October 2014 | 389 | 108 | Scottish Power Renewables and Ørsted | Officially opened 30 October 2014.[105] | 2 | |

| Westermost Rough | May 2015[106] | 210 | 35 | Ørsted | Offshore construction started beginning of 2014.[107] First use of 6MW turbine.[108] | 2 | |

| Humber Gateway | June 2015[109] | 219 | 73 | E.ON Energy UK, Balfour Beatty and Equitix | First monopole installed September 2013[110] | 2 | |

| Gwynt y Môr | June 2015[111] | 576 | 160 | RWE Npower Renewables | Construction started January 2012.[112] Final commissioning was completed on 18 June 2015.[111] | 2 | |

| Dudgeon | October 2017[113] | 402 | 67 | Equinor and Statkraft | Consent granted July 2012[114] Application for Variation in July 2013 to increase area and reduce capacity.[115] Eligible for UK Government CfD[116] Construction began in March 2016.[117] | 2 | |

| Hywind Scotland | October 2017[118] | 30 | 5 | Statoil | Planning application submitted May 2015. Floating wind farm.[119] Planning consented in November 2015.[120] | Demo | |

| Blyth Offshore Demonstrator Project | October 2017 [121] | 58 | 10 | EDF Energy | Consent granted.[122] | Demo | |

| Race Bank | February 2018[123] | 573 | 91 | Ørsted and Macquarie Group | Consent granted July 2012[124] | 2 | |

| Aberdeen Bay (EOWDC) | September 2018[125] | 92 | 11 | Vattenfall | Demonstration site for new turbines. Consent granted March 2013.[126] Project under construction. Use of 8MW turbines planned utilising the Vestas "short tower" option. | Demo | |

| Kincardine (Phase 1) | October 2018 | 2 | 1 | Kincardine Offshore Wind | Consent granted March 2017[127][128][129][130] Commercial scale demonstration of a floating wind farm.[131][132] | Demo | |

| Rampion | November 2018[133] | 400 | 116 | E.ON Energy UK | Construction began in January 2016.[11] First electricity delivered to the grid in November 2017.[134] | 3 | |

| Beatrice | July 2019[135] | 588 | 84 | SSE plc, Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and Red Rock Power LTD | Offshore pile construction has started.[136] Eligible for government CfD.[116] First power generated in July 2018.[137] Fully operational in June 2019 [83] | STW. | |

| Hornsea Project One | January 2020[138] | 1218 | 174 | Ørsted | Offshore construction began in January 2018.[139] First power in March 2019.[140] Eligible for government CfD.[116] Use of 7MW turbines planned.[140] | 3 | |

| East Anglia ONE | July 2020[141] | 714 | 102 | Vattenfall and Scottish Power Renewables | Consent granted June 2014.[142][143] Uses 7MW turbines. Turbine installation was completed in April 2020.[144] | 3 | |

| Kincardine (Phase 2) | 2021[145] | 48 | 5 | Kincardine Offshore Wind | Consent granted March 2017[127] First turbine towed into place in August 2018 and first power generated in October 2018.[128][129][130] Commercial scale demonstration of a floating wind farm.[131][132] | Demo | |

| Triton Knoll | 2021–22 (Phase 1)[146] | 860 | 90 | Innogy | Consent granted July 2013 [147] Use of 9.5MW turbines planned. All foundations completed in August 2020.[148] | 2 | |

| Moray East | 2022–23 (Phase 1)[146] | 950 | 100 | EDP Renováveis | Consent granted March 2014.[149] Use of 9.5MW turbines planned. Foundations set to be installed end of Q1 2020.[150] | 3 | |

| Hornsea Project Two | 2022–23 (Phase 1)[146] | 1386 | 165 | Ørsted | Consent granted August 2016 for phase 2 (Breesea & Optimus Wind – 900MW each).[151] Project in pre-construction phase. Use of 8MW turbines planned. | 3 | |

| Neart Na Gaoithe | 2023[152] | 448 | 54 | EDF Energy | Consent granted October 2014.[153] Use of 8MW turbines planned. Construction began in August 2020.[154] | STW | |

| Dogger Bank A | 2023–24 [155][156] | 1200 | 95 | SSE plc and Equinor | Consent granted February 2015 for phase 1 (Creyke Beck A & B – 1200MW each)[157] Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction.[155] The wind farm will use 95 of the GE Haliade-X 13MW, the worlds largest offshore wind turbine.[158] | 3 | |

| Dogger Bank B | 2024–25[155] | 1200 | 95 | SSE plc and Equinor | Consent granted February 2015 for phase 1 (Creyke Beck A & B – 1200MW each)[157] Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction.[155] The wind farm will use 95 of the GE Haliade-X 13MW, the worlds largest offshore wind turbine.[158] | 3 | |

| Seagreen (Phase 1) | 2024–25 (Phase 1)[155][159] | 1075 | 114 | SSE and Seagreen Wind Energy Ltd | Consent granted October 2014 for phase 1 (Alpha & Bravo – 525MW each)[153] RSPB Judicial Review overturned. Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction.[155] The project is projected to grow to 1500MW after the phase 1 | ||

| Dounreay Trì | Q1 2020[160] | 10 | 2 | Hexicon AB and Dounreay Tri | Consent granted March 2017.[161] Has since been put on hold [162] | ||

| East Anglia THREE | 2023[163] | 1400 | 121 | Scottish Power Renewables, Vattenfall and OPR | Consent granted August 2017.[164] | 3 | |

| ForthWind Offshore Wind Demonstration Project | 2023–24[155] | 12 | 2 | Cierco | Consent granted December 2016.[165] | ||

| Sofia | 2023–24 (Phase 1)[155] | 1400 | 100 | Innogy | Consent granted August 2015.[166] Formerly known as Dogger Bank Teesside B. Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction[155] | 3 | |

| Inch Cape | 2024[167] | 784 | 72 | Red Rock Power LTD | Consent granted October 2014.[153] RSPB Judicial Review overturned.[168] Project downsized to 784MW following issues raised during consultations. New application in August 2018 with fewer but taller turbines.[169] | STW | |

| Moray West | 2024[170] | 850 | 85 | EDP Renováveis | Consent granted June 2019.[171] | ||

| Dogger Bank C | 2024–25 (Phase 1)[155][172] | 1200 | 95 | SSE plc and Equinor | Formerly known as Teesside A. Consent granted August 2015.[166] Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction.[155] The wind farm is planning to use the Haliade-X 12MW from GE, the world's largest wind turbine[173] | 3 | |

| Hornsea Project Three | 2025 | 2400 | 231 | Ørsted | Consent granted in 2020.[174] The earliest date that the project is expected to start construction is 2021.[175] The earliest date that the project is set to be operational is 2025[176] | 3 | |

| Hornsea Project Four | 2027 | 180 | Ørsted | Anticipated development consent order is expected to be submitted in 2020.[177] The wind farm is expected to start construction in 2023, and operation at 2027 at the earliest[178] The project's capacity is unknown by Orsted due to the ever increasing size of available wind turbines to the project. | |||

| Norfolk Vanguard | Mid 2020s | 1800 | 90 - 180 | Vattenfall | A development consent order was given for the project in June 2020.[179] The project aims to install all of the offshore cabling for the Vanguard location as well as the sister wind farm, Boreas which is located adjacent to the project.[180] | 3 | |

| Norfolk Boreas | Mid to late 2020s | 1800 | unknown | Vattenfall | A development consent order is expected to be given to the project in 2021. The project is expected to be built quickly as the offshore cabling will be laid down whilst the sister wind farm Vanguard is constructed. | ||

Onshore

The first commercial wind farm was built in 1991 at Delabole in Cornwall;[182] it consisted of 10 turbines each with a capacity to generate a maximum of 400 kW. Following this, the early 1990s saw a small but steady growth with half a dozen farms becoming operational each year; the larger wind farms tended to be built on the hills of Wales, examples being Rhyd-y-Groes, Llandinam, Bryn Titli and Carno. Smaller farms were also appearing on the hills and moors of Northern Ireland and England. The end of 1995 saw the first commercial wind farm in Scotland go into operation at Hagshaw Hill. The late 1990s saw sustained growth as the industry matured. In 2000 the first turbines capable of generating more than 1 MW were installed and the pace of growth started to accelerate as the larger power companies like Scottish Power and Scottish and Southern became increasingly involved in order to meet legal requirements to generate a certain amount of electricity using renewable means (see Renewables obligations below). Wind turbine development continued rapidly and by the mid-2000s 2 MW+ turbines were the norm. In 2007, the German wind turbine producer Enercon installed the first 6 MW model ("E-126"); The nameplate capacity was changed from 6 MW to 7 MW after technical revisions were performed in 2009 and to 7.5 MW in 2010.

Growth continued with bigger farms and larger, more efficient turbines sitting on taller and taller masts. Scotland's sparsely populated, hilly and windy countryside became a popular area for developers and the United Kingdom's first 100 MW+ farm went operational in 2006 at Hadyard Hill in South Ayrshire.[183] 2006 also saw the first use of the 3 MW turbine. In 2008 the largest onshore wind farm in England was completed on Scout Moor[184] and the repowering of the Slieve Rushen Wind Farm created the largest farm in Northern Ireland.[185] In 2009 the largest wind farm in the United Kingdom went live at Whitelee on Eaglesham Moor in Scotland.[186] This is a 539 MW wind farm consisting of 215 turbines. Approval has been granted to build several more 100 MW+ wind farms on hills in Scotland and will feature 3.6 MW turbines.

As of September 2013, there were 458 operational onshore wind farms in the United Kingdom with a total of 6565 MW of nameplate capacity. A further 1564 MW of capacity is currently being constructed, while another 4.8 GW of schemes have planning consent.[43]

In 2009, United Kingdom onshore wind farms generated 7,564 GW·h of electricity; this represents a 2% contribution to the total United Kingdom electricity generation (378.5 TW·h).[187]

Large onshore wind farms are usually directly connected to the National Grid, but smaller wind farms are connected to a regional distribution network, termed "embedded generation". In 2009 nearly half of wind generation capacity was embedded generation, but this is expected to reduce in future years as larger wind farms are built.[188]

Gaining planning permission for onshore wind farms continues to prove difficult, with many schemes stalled in the planning system and a high rate of refusal.[189][190] The RenewableUK (formerly BWEA) figures show that there are approximately 7,000 MW worth of onshore schemes waiting for planning permission. On average, a wind farm planning application takes 2 years to be considered by a local authority, with an approval rate of 40%. This compares extremely unfavourably with other types of major applications, such as housing, retail outlets and roads, 70% of which are decided within the 13- to 16-week statutory deadline; for wind farms the rate is just 6%. Approximately half of all wind farm planning applications, over 4 GW worth of schemes, have objections from airports and traffic control on account of their impact on radar. In 2008 NATS en Route, the BWEA, the Ministry of Defence and other government departments signed a Memorandum of Understanding seeking to establish a mechanism for resolving objections and funding for more technical research.

Wind farms in the UK often have to meet a maximum height limit of 125 metres (excluding Scotland). However, modern lower cost wind turbines installed on the continent are over 200 metres tall.[191] This planning criteria has stunted the development of onshore wind in the UK.

List of the largest operational and proposed onshore wind farms

| Wind farm | County | Country | Turbine model | Power (MW) each turbine |

No. Turbines | Total capacity (MW) |

Commiss- ioned |

Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal Rig | Scottish Borders | Scotland | Nordex N80/ Siemens SWT-2.3 | 2.5/2.3 | 25/60 | 200.5 | May 2004 | Extended May 2007 (1a) & September 2010 (2 & 2a) |

| Cefn Croes | Ceredigion | Wales | GE 1.5 se | 1.5 | 39 | 58.5 | June 2005 | |

| Black Law | South Lanarkshire | Scotland | Siemens SWT-2.3 | 2.3 | 88 | 124 | September 2005 | Extended September 2006 (Phase 2) |

| Hadyard Hill | South Ayrshire | Scotland | Bonus B2300 | 2.5 | 52 | 120 | March 2006 | |

| Farr | Highland | Scotland | Bonus B2300 | 2.3 | 40 | 92 | May 2006 | |

| Slieve Rushen | Co Fermanagh | Northern Ireland | Vestas V90 | 3 | 18 | 54 | April 2008 | Largest onshore farm in Northern Ireland |

| Scout Moor | Lancashire | England | Nordex N80 | 2.5 | 26 | 65 | September 2008 | |

| Little Cheyne Court | Kent | England | Nordex 2.3 | 2.3 | 26 | 59.8 | November 2008 | |

| Whitelee | East Renfrewshire | Scotland | Siemens SWT-2.3 | 2.3 | 140 | 322 | November 2008 | Largest operational onshore wind farm in the United Kingdom |

| Arecleoch | South Ayrshire | Scotland | Gamesa G87[192] | 2 | 60 | 120 | June 2011 | Construction began October 2008, completed in June 2011[193] |

| Griffin | Perth & Kinross | Scotland | Siemens SWT-2.3[194] | 2.3 | 68 | 156.4 | February 2012 | Construction began August 2010, completed in February 2012[195] |

| Clyde | South Lanarkshire | Scotland | Siemens SWT-2.3 | 2.3 | 152 | 350 | September 2012 | Construction began January 2010, completed in September 2012[196] |

| Fallago Rig | Scottish Borders | Scotland | Vestas V90[197] | 3 | 48 | 144 | April 2013 | Construction finished April 2013[198] |

| Whitelee extension | East Renfrewshire | Scotland | Alstom ECO 100/ECO 74 | 3/1.6 | 69/6 | 217 | April 2013 | Construction finished April 2013[199] |

| Keadby Wind Farm | Lincolnshire | England | Vestas V90 | 2 | 34 | 68 | July 2014 | First power produced September 2013, England's largest onshore wind farm, Completed July 2014 [200] |

| Harestanes | Dumfries & Galloway | Scotland | Gamesa G87 | 2 | 68 | 136 | July 2014 | [201] |

| Clashindarroch Wind Farm | Aberdeenshire | Scotland | Senvion MM82 | 2.05 | 18 | 36.9 | March 2015 | Construction began June 2013[202] |

| Bhlaraidh | Highland | Scotland | Vestas V112/V117 | 3.45 | 32 | 108 | August 2017 | All 32 turbines connected to the grid.[203] |

| Pen y Cymoedd | Neath Port Talbot & Rhondda Cynon Taf | Wales | Siemens SWT-3.0 | 3 | 76 | 228 | September 2017 | Officially opened on 28 September.[204] Largest onshore wind farm in Wales. |

| Kilgallioch (Arecleoch Phase 2) | Dumfries & Galloway | Scotland | Gamesa G90/G114 | 2.5 | 96 | 239 | 2017 | [205] |

| Clyde Extension | South Lanarkshire | Scotland | Siemens SWT-3.0 | 3.2 | 54 | 172.8 | 2017 | [206] |

| Stronelairg | Highland | Scotland | 3.45 | 66 | 227 | December 2018[207] | Construction started March 2017[208] First power in March 2018.[209] | |

| Dorenell | Moray | Scotland | 3 | 59 | 177 | March 2019[210][211] | Last turbine base completed in September 2018.[212] | |

| Viking Wind Farm | Shetland Islands | Scotland | 4.3 | 103 | 443 | estimated 2024 | Consent granted April 2012 with reduced number of turbines. Construction started in 2020.[213][214] | |

| Stornoway | Western Isles | Scotland | 5 | 36 | 180 | Consent granted in 2012. First use of 5MW turbines onshore. | ||

| Muaitheabhal | Western Isles | Scotland | 3.6 | 33 | 189 | estimated 2023/2024 | Halted in October 2014 due to external delays[215] Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction[155] | |

| Hesta Head | Orkney Isles | Scotland | 4.08 | 5 | 20.40 | estimated 2023/2024 | Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction[155] | |

| Druim Leathann | Western Isles | Scotland | 49.50 | estimated 2024/2025 | Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction[155] | |||

| Costa Head | Orkney Isles | Scotland | 4.08 | 4 | 16.32 | estimated 2023/2024 | Successful in the spring 2019 capacity auction[155] | |

| Llandinam – Repower | Powys | Wales | 3 | 34 | 102 | Consent granted in 2015. | ||

| South Kyle | Dumfries & Galloway | Scotland | 3.4 | 50 | 170 | Consent granted in 2017. Final investment decision to be made by spring 2019.[216] |

Economics

Early windfarms, were part financed through the Renewables Obligation where British electricity suppliers were required by law to provide a proportion of their sales from renewable sources such as wind power or pay a penalty fee. The supplier then received a Renewables Obligation Certificate (ROC) for each MW·h of electricity they have purchased.[16] The Energy Act 2008 introduced banded ROCs for different technologies from April 2009. Onshore wind receives 1 ROC per MW·h, however following the Renewables Obligation Banding Review in 2009 offshore wind then received 2 ROCs to reflect its higher costs of generation.[217] Wind energy received approximately 40% of the total revenue generated by the RO.[218] The ROCs were the principal form of support for United Kingdom wind power, providing over half of the revenue from wind generation for early wind farms.

A 2004 study by the Royal Academy of Engineering using "simplification and approximation" found that wind power cost 5.4 pence per kW·h for onshore installations and 7.2 pence per kW·h for offshore, compared to 2.2p/kW·h for gas and 2.3p/kW·h for nuclear.[219] By 2011 onshore wind costs at 8.3p/kW·h had fallen below new nuclear at 9.6p/kW·h, though it had been recognised that offshore wind costs at 16.9p/kW·h were significantly higher than early estimates mainly due to higher build and finance costs, according to a study by the engineering consultancy Mott MacDonald.[220] Wind farms are made profitable by subsidies through Renewable Obligation Certificates which provide over half of wind farm revenue.[221] The total annual cost of the Renewables Obligation topped £1 billion in 2009 and is expected to reach £5 billion by 2020, of which about 40% is for wind power.[222] This cost is added to end-user electricity bills. Sir David King has warned that this could increase UK levels of fuel poverty.[223]

However, as the technology developed the cost of electricity generation by wind has fallen significantly. In the 2019 CfD round, 6GW of wind was added to the grid at £47/MWh at 2019 prices; the first round that prices were lower than current generation costs.[25][26]

The government announced on 18 June 2015 that it intended to close the Renewables Obligation to new onshore wind power projects on 1 April 2016 (bringing the deadline forward by one year).[224] Support for offshore wind was moved into the government's Contract for Difference support regime.[225]

As of 2020 costs for offshore wind power stations is the lowest cost of any other UK electricity generation, less than 50% of the cost of Nuclear Power (before balancing/storage costs).[226][227]

Variability and related issues

| Daytime | Overnight | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter | 44% | 36% | 38% |

| Summer | 31% | 13% | 20% |

Wind-generated power is a variable resource, and the amount of electricity produced at any given point in time by a given plant will depend on wind speeds, air density and turbine characteristics (among other factors). If wind speed is too low (less than about 2.5 m/s) then the wind turbines will not be able to make electricity, and if it is too high (more than about 25 m/s) the turbines will have to be shut down to avoid damage. When this happens other power sources must have the capacity to meet demand.[53][229] Three reports on the wind variability in the United Kingdom issued in 2009, generally agree that variability of the wind does not make the grid unmanageable; and the additional costs, which are modest, can be quantified.[230] For wind power market penetration of up to 20% studies in the UK show a cost of £3-5/MWh.[231] In the United Kingdom, demand for electricity is higher in winter than in summer and so are wind speeds.[232][233]

While the output from a single turbine can vary greatly and rapidly as local wind speeds vary, as more turbines are connected over larger and larger areas the average power output becomes less variable.[234] Studies by Graham Sinden suggest that, in practice, the variations in thousands of wind turbines, spread out over several different sites and wind regimes, are smoothed, rather than intermittent. As the distance between sites increases, the correlation between wind speeds measured at those sites, decreases.[228][235]

Constraint payment

A Scottish government spokesman has said electricity generated by renewables accounted for 27% of Scotland's electricity use. On the night of 5–6 April 2011, the wind in Scotland was high, it was raining heavily, which also created more hydroelectricity than normal. The grid became overloaded preventing transmission of the electrical power to England, as a result the electrical wind power generation was cut. Wind farms operators were paid compensation known as "constraint payments"[236] as a result (a total of approximately £900,000) by the National Grid, estimated at twenty times the value of electricity that would have been generated. A spokesman for the Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC), described the occurrence as unusual, and noted it demonstrated a need for greater energy storage capacity and better electrical power distribution infrastructure.[237][238][239] The payment of 'constraint payments' to wind energy suppliers is one source of criticism of the use wind power and its implementation; in 2011 it was estimated that nearly £10 million in constraint payments would be received, representing ten times the value of the potential lost electricity generation.[240] Wind farm constraint payments have increased substantially year on year reaching a record of £139 million in 2019.[241] Nevertheless, constraint payments are a normal part of operating the UK grid, and similar amounts are also paid to each of gas, coal and other generators.[242][243]

Backup and Frequency Response

There is some dispute over the necessary amount of reserve or backup required to support the large-scale use of wind energy due to the variable nature of its supply. In a 2008 submission to the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, E.ON UK argued that it is necessary to have up to 80–90% backup.[244] Other studies give a requirement of 15% to 22% of installed intermittent capacity.[231] National Grid which has responsibility for balancing the grid reported in June 2009 that the electricity distribution grid could cope with on-off wind energy without spending a lot on backup, but only by rationing electricity at peak times using a so-called "smart grid", developing increased energy storage technology and increasing interconnection with the rest of Europe.[245][246] In June 2011 several energy companies including Centrica told the government that 17 gas-fired plants costing £10 billion would be needed by 2020 to act as back-up generation for wind. However, as they would be standing idle for much of the time they would require "capacity payments" to make the investment economic, on top of the subsidies already paid for wind. In 2015/2016 National Grid contracted 10 coal and gas-fired plants to keep spare capacity on standby for all generation modes, at a cost of £122 million, which represented 0.3% of an average electricity bill.[247]

Grid scale battery storage is being developed in order to cope with the variability in wind power. As of 2020, there are no operational large scale Grid storage batteries.

With the increase in proportion of energy being generated by wind on the UK grid, there is a significant reduction in synchronous generation. Therefore, in order to ensure grid stability, the National grid ESO is piloting a range of demand side and supply side frequency response products.[248]

Public opinion

Surveys of public attitudes across Europe and in many other countries show strong public support for wind power.[5][6][7] About 80 percent of EU citizens support wind power.[8]

|

A 2003 survey of residents living around Scotland's 10 existing wind farms found high levels of community acceptance and strong support for wind power, with much support from those who lived closest to the wind farms. The results of this survey support those of an earlier Scottish Executive survey 'Public attitudes to the Environment in Scotland 2002', which found that the Scottish public would prefer the majority of their electricity to come from renewables and which rated wind power as the cleanest source of renewable energy.[250] A survey conducted in 2005 showed that 74% of people in Scotland agree that wind farms are necessary to meet current and future energy needs. When people were asked the same question in a Scottish renewables study conducted in 2010, 78% agreed. The increase is significant as there were twice as many wind farms in 2010 as there were in 2005. The 2010 survey also showed that 52% disagreed with the statement that wind farms are "ugly and a blot on the landscape". 59% agreed that wind farms were necessary and that how they looked was unimportant.[9] Scotland is planning to obtain 100% of electricity from renewable sources by 2020.[10]

A British 2015 survey showed 68% support and 10% opposition to onshore wind farms.[251]

Politics

In the UK, the ruling Conservative government is opposed to further onshore wind turbines and has cancelled subsidies for new onshore wind turbines from April 2016.[252] The former prime minister David Cameron stated that “We will halt the spread of onshore wind farms",[253] and claimed that "People are fed up with onshore wind" though polls of public opinion showed the converse.[254] Leo Murray of 10:10 said, “It looks increasingly absurd that the Conservatives have effectively banned Britain’s cheapest source of new power.”[227] As the UK's Conservative government was opposed to onshore wind power it attempted to cancel existing subsidies for onshore wind turbines a year early from April 2016, although the House of Lords struck those changes down.[255]

The wind power industry has claimed that the policy will increase electricity prices for consumers as onshore wind is one of the cheapest power technologies,[253] although the government disputes this,[252] and it is estimated that 2,500 turbines will not now be built.[252] Questions have been raised about whether the country will now meet its renewable obligations, as Committee on Climate Change has stated that 25GW of onshore wind may be needed by 2030.[256]

In 2020 the Boris Johnson led government decided to stop the block on onshore wind power, and from 2021 onshore wind developers will be able to compete in subsidy auctions with solar power and offshore wind.[257] On 24 September 2020, Boris Johnson reaffirmed his commitment to renewables, especially wind power and Nuclear in the United Kingdom. He said that the UK can be the "Saudi Arabia of wind power",[258] and that

We've got huge, huge gusts of wind going around the north of our country—Scotland. Quite extraordinary potential we have for wind[259]

Records

December 2014 was a record breaking month for UK wind power. A total of 3.90 TWh of electricity was generated in the month – supplying 13.9% of the UK's electricity demand.[260] On 19 October 2014, wind power supplied just under 20% of the UK's electrical energy that day. Additionally, as a result of 8 of 16 nuclear reactors being offline for maintenance or repair, wind produced more energy than nuclear did that day.[261][262] The week starting 16 December 2013, wind generated a record 783,886 MWh – providing 13% of Britain's total electricity needs that week. And on 21 December, a record daily amount of electricity was produced with 132,812 MWh generated, representing 17% of the nation's total electricity demand on that day.[263]

In January 2018 metered wind power peaked at over 10 GW and contributed up to a peak of 42% of the UK's total electricity supply.[264] In March, maximum wind power generation reached 14 GW, meaning nearly 37% of the nation's electricity was generated by wind power operating at over 70% capacity.[265] On 5 December 2019, maximum wind power generation reached 15.6 GW.[266] At around 2am on 1 July 2019, wind power was producing 50.64% of the electricity supply, perhaps the first time that over half of the UK's electricity was produced by wind,[267] while at 2:00am on 8 February 2019, wind power was producing 56.05% of the electricity supply.[268] Wind power first exceeded 16GW on 8 December 2019 during Storm Atiyah.[269]

On Boxing Day 2020, a record 50.67% of power used in the United Kingdom was generated by wind power. However, it was not the highest amount of power ever generated by wind turbines; that came earlier in December 2020, when demand was higher than on Boxing Day and wind turbines supplied 40% of the power required by the National Grid (17.3 GW).[270][271]

Manufacturing

As of 2020, there are no major UK-based wind turbine manufacturers: most are headquartered in Denmark, Germany and the USA.

In 2014, Siemens announced plans to build facilities for offshore wind turbines in Kingston upon Hull, England, as Britain's wind power rapidly expands. The new plant was expected to begin producing turbine rotor blades in 2016. By 2019 blades were being shipped in large numbers [272] The plant and the associated service centre, in Green Port Hull nearby, will employ about 1,000 workers. The facilities will serve the UK market, where the electricity that major power producers generate from wind grew by about 38 percent in 2013, representing about 6 percent of total electricity, according to government figures. At the time there were plans to continue to increase Britain's wind-generating capacity, to 14 gigawatts by 2020.[49] In fact, that figure was exceeded in late 2015.

On 16 October 2014, TAG Energy Solutions announced the mothballing and semi closure of its Haverton Hill construction base near Billingham with between 70 and 100 staff redundancies after failing to secure any subsequent work following the order for 16 steel foundations for the Humber Estuary in East Yorkshire.[273]

In June 2016 Global Energy Group announced it had signed a contract in association with Siemens to fabricate and assemble turbines for the Beatrice Wind Farm, at its Nigg Energy Park site. It hopes in the future to become a centre for excellence and has opened a skills academy to help re-train previous offshore workers for green energy projects.[82]

Specific regions

Wind power in Scotland

Wind power is Scotland's fastest growing renewable energy technology, with 5328 MW of installed capacity as of March 2015. This includes 5131 MW of onshore wind and 197 MW of offshore wind.[274]

Whitelee Wind Farm near Eaglesham, East Renfrewshire is the largest onshore wind farm in the United Kingdom with 215 Siemens and Alstom wind turbines and a total capacity of 539 MW.[275] Clyde Wind Farm near Abington, South Lanarkshire is the UK's second largest onshore wind farm comprising 152 turbines with a total installed capacity of 350 MW.[276] There are many other large onshore wind farms in Scotland, at various stages of development, including some that are in community ownership.

Robin Rigg Wind Farm in the Solway Firth is Scotland's only commercial-scale, operational offshore wind farm. Completed in 2010, the farm comprises 60 Vestas turbines with a total installed capacity of 180 MW.[277] Scotland is also home to two offshore wind demonstration projects: The two turbine, 10 MW Beatrice Demonstrator Project located in the Moray Firth, has led to construction of the 84 turbine, 588MW Beatrice Wind Farm set to begin in 2017 and the single turbine, 7 MW Fife Energy Park Offshore Demonstration Wind Turbine in the Firth of Forth. There are also several other commercial-scale and demonstration projects in the planning stages.[278]

The siting of turbines is often an issue, but multiple surveys have shown high local community acceptance for wind power in Scotland.[279][280][281] There is further potential for expansion, especially offshore given the high average wind speeds, and a number of large offshore wind farms are planned.

The Scottish Government has achieved its target of generating 50% of Scotland's electricity from renewable energy by 2015, and is hoping to achieve 100% by 2020. The majority of this is likely to come from wind power.[282] This target will also be met if current trends continue [283][284]

In July 2017 work commissioning an experimental floating wind farm known as Hywind at Peterhead began. The wind farm is expected to supply power to 20,000 homes. Manufactured by Statoil, the floating turbines can be located in water up to a kilometre deep.[285] In its first two years of operation the facility with five floating wind turbines, giving a total installed capacity of 30 MW, has averaged a capacity factor in excess of 50% [286]

Whitelee Wind Farm with the Isle of Arran in the background.

Whitelee Wind Farm with the Isle of Arran in the background.

Ardrossan Wind Farm from Portencross, just after sunrise

Ardrossan Wind Farm from Portencross, just after sunrise

See also

- Related lists

- Related United Kingdom pages

- Renewable energy in the United Kingdom

- Renewable energy in Scotland

- Solar power in the United Kingdom

- Geothermal power in the United Kingdom

- Biofuel in the United Kingdom

- Hydroelectricity in the United Kingdom

- Energy in the United Kingdom

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- Energy policy of the United Kingdom

- Green electricity in the United Kingdom

- Developers and operators

- Other related

References

- "Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics, 2019 (Chart 5.6 and Chart 6.4)" (PDF). BEIS. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "UK Renewable Energy Roadmap Crown copyright, July 2011" (PDF). Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Lu, Xi, Michael B. McElroy, and Juha Kiviluoma. 2009. "Global potential for wind-generated electricity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106(27): 10933-10938.

- Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics, 2019 (PDF). BEIS. Chart 5.6 and Chart 6.4. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Wind Energy and the Environment" (PDF). Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- "A Summary of Opinion Surveys on Wind Power" (PDF). Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- "Public attitudes to wind farms". Eon-uk.com. 28 February 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- "The Social Acceptance of Wind Energy". European Commission. Archived from the original on 28 March 2009.

- "Rise in Scots wind farm support". BBC News. 19 October 2010.

- "An investigation into the potential barriers facing the development of offshore wind energy in Scotland" (PDF). 7 March 2012.

- "UK Wind Energy Database (UKWED)". RenewableUK. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Wind power production for main countries". thewindpower.net. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Queen's Speech December 2019" (PDF). GOV.UK. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "G. B. National Grid status". www.gridwatch.templar.co.uk. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Ziady, Hanna (6 October 2020). "All 30 million British homes could be powered by offshore wind in 2030". CNN. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Renewables Obligation. Ofgem.gov.uk.

- "Chapter 6: Renewable sources of energy" (PDF). Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics (DUKES). Department of Energy & Climate Change. pp. 159–162.

- Association, Press (2 March 2015). "British public thinks wind power subsidies are 14 times higher than reality". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Cost Reduction Monitoring Framework". ORE Catapult. February 2015. pp. 7 and. Archived from the original (pdf) on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- UK wind power overtakes coal for first time The Guardian

- Wilson, Grant. "Winds of change: Britain now generates twice as much electricity from wind as coal". The Conversation. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- "Wind power overtakes nuclear for first time in UK across a quarter'". The Guardian. 16 May 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/566567/BEIS_Electricity_Generation_Cost_Report.pdf "ELECTRICITY GENERATION COSTS" Check

|url=value (help) (PDF). www.gov.uk. BEIS. November 2016. Retrieved 6 December 2016. - Clark, Pilita (23 January 2017). "UK wind farm costs fall almost a third in 4 years". Financial Times. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- Evans-Pritchard, Ambrose (20 September 2019). "Rejoice: Britain's huge gamble on offshore wind has hit the jackpot". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Clean energy to power over seven million homes by 2025 at record low prices". GOV.UK. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- "Digest of UK energy statistics (DUKES)". decc.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Department of Energy and Climate Change". Archived from the original on 23 December 2012.

- "DECC Energy Trends March 2014" (PDF). Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Wind in power – 2014 European statistics" (PDF). 16 February 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "Wind in power – 2015 European statistics" (PDF). 5 February 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "BEIS renewables statistics" (PDF). Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Wind power grows 45%". Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "BEIS renewables statistics" (PDF). Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "Wind energy in Europe in 2018" (PDF). 21 February 2019. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/wind-power-coal-climate-change-renewable-energy-a9273541.html

- Price, Trevor J. (2004). "Blyth, James (1839–1906)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/100957. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Anon. "Costa Head Experimental Wind Turbine". Orkney Sustainable Energy Website. Orkney Sustainable Energy Ltd. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- Peter Musgrove (9 December 1976). "Windmills change direction". New Scientist. New Scientist Careers Guide : The Employer Contacts Book for Scientists. 72. pp. 596–7. ISSN 0262-4079.

- McKenna, John. (8 April 2009) New Civil Engineer – Wind power: Chancellor urged to use budget to aid ailing developers. Nce.co.uk.

- Paul Eccleston (4 October 2007). "Britain's massive offshore wind power potential". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- RenewableUK news article – Wind farms hit high of more than 12% of UK electricity demand Archived 22 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Bwea.com (6 January 2012).

- "Contact with BWEA Admin". Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- "Record-Breaking Year for UK Offshore Wind" Offshorewind.biz, 6 November 2013. Accessed: 6 November 2013.

- "London Array wind farm opened by Prime Minister". BBC News. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "DECC Energy trends statistics section 6: renewables" (PDF). Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- RenewableUK. "RenewableUK – RenewableUK News – Electricity needs of more than a quarter of UK homes powered by wind in 2014". renewableuk.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Vaughan, Adam (1 December 2016). "Hull's Siemens factory produces first batch of wind turbine blades". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- Stanley Reedmarch (25 March 2014). "Siemens to Invest $264 Million in British Wind Turbine Project". New York Times.

- RenewableUK. "RenewableUK – RenewableUK News – New-records-set-in-best-ever-year-for-British-wind-energy-generation". renewableuk.com. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- Wind turbines 'could supply most of UK's electricity' The Guardian 8 November 2016

- Jha, Alok (21 October 2008). "UK overtakes Denmark as world's biggest offshore wind generator". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 November 2008.

- Oswald, James; Raine, Mike; Ashraf-Ball, Hezlin (June 2008). "Will British weather provide reliable electricity?" (PDF). Energy Policy. 36 (8): 2312–2325. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.04.033.

- National Grid Table of Indicative Triad Demand Information showing 7 January 2010 peak Archived 18 January 2013 at Archive.today. Bmreports.com.

- MacKay, David. Sustainable Energy – without the hot air. pp. 60–62. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- "Two Terawatts average power output: the UK offshore wind resource". Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- RenewableUK – Offshore Wind Introduction Archived 29 July 2012 at Archive.today. Bwea.com.

- REPP report into Non-Fossil Fuel subsidies in the UK. Repp.org (30 June 1998).

- Huge boost for renewables as offshore windfarm costs fall to record low The Guardian

- UK built half of Europe's offshore wind power in 2017 The Guardian

- Ziady, Hanna (6 October 2020). "All 30 million British homes could be powered by offshore wind in 2030". CNN. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "The Crown Estate map of Operational Offshore energy – Round 1 wind farms in red" (PDF). Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "The Crown Estate – Our portfolio". The Crown Estate. Archived from the original on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Collett News: UK's Largest Turbine Blades to Muirhall Wind Farm – Collett Transport". collett.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "The Crown Estate map of Operational Offshore energy – Round 2 wind farms in pink" (PDF). Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "The Crown Estate R1 & R2 extensions announcement". Archived from the original on 24 August 2010.

- "Map of R1 & R2 wind farm extensions, The Crown Estate" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2011.

- Round 3 developers, The Crown Estate Archived 2 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Thecrownestate.co.uk.

- "Map of R3 Zones, The Crown Estate" (PDF). Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "World's Largest Offshore Wind Farm Fully Up and Running". OffshoreWIND.biz. 30 January 2020.

- "National Infrastructure Planning: Hornsea Project Three Offshore Wind Farm". Planning Inspectorate. 31 December 2020.

- Macalister, Terry (11 September 2015). "Tories reject Navitus Bay offshore windfarm". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "RWE Innogy – Press release 09 July 2013 Export cables in at Gwynt y Môr Offshore Wind Farm". rwe.com. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Centrica Celtic Array Project website". Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Offshore Wind Leasing Round 4 | The Crown Estate". www.thecrownestate.co.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Vaughan, Adam (4 February 2020). "UK coal phase-out date pulled forward". Business Green. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- Vaughan, Adam (10 April 2018). "EDF warns of delays at Flamanville nuclear power station in France". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Vaughan, Adam (4 August 2015). "Public support for UK nuclear and shale gas falls to new low". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Queen's Speech: Government ramps up offshore wind target to 40GW". www.businessgreen.com. 19 December 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- – Scottish Government Blue Seas – Green Energy Report. Scotland.gov.uk (18 March 2011).

- Table of Scottish Offshore Zones, The Crown Estate Archived 9 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Thecrownestate.co.uk.

- "Major boost to far north economy as Nigg is awarded Beatrice contract – and Helmsdale may benefit too". www.northern-times.co.uk. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- https://www.beatricewind.com"

- "Review of offshore wind farm development". sse.com. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- BBC News report-SSE ditches plans for Kintyre offshore wind farm. Bbc.co.uk (1 March 2011).

- Fred.Olsen Forth Array News Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Fortharray.com.

- SSE Project website. Sse.com.

- argyllarray.com. 29 April 2015 http://www.argyllarray.com/news-detail.asp?item=195. Retrieved 9 June 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - – UKWED Offshore wind farms Archived 25 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine. renewableuk.com.

- "Showtime at Burbo 2". 27 April 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "RWE Innogy – Construction update – December 2009". rwe.com. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Milestones". gunfleetsands.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- Walney opens for business RE News Europe, 9 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- "World's largest offshore wind farm opens". BBC News. 6 September 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- businessGreen news website. Businessgreen.com.

- Offshore Wind News. Offshorewind.biz (7 September 2012).

- "Full throttle for 353MW UK offshore wind farm – Energy Live News – Energy Made Easy". 3 April 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Sheringham Shoal. Scira.co.uk.

- 4C Offshore database – London Array. 4coffshore.com (18 December 2006).

- E.ON UK Press release. eon-uk.com Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- 4C Offshore database – London Array. 4coffshore.com.

- Fiona Harvey (19 February 2014). "Migrating birds halt expansion of London Array". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Lincs OWF: Centrica Expresses Gratitude to Local Community (UK)". Offshore Wind. 4 July 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- The Courier – Blades turn at Methil Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Official opening following full power at West of Duddon Sands Offshore Windfarm". scottishpowerrenewables.com. 30 October 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Westermost Rough hits full power". reNEWS – Renewable Energy News. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Offshore Installation Update". dongenergy-humberregion.co.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Dong energy Westermost Rough project summary". Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Eon energy project sees every turbine generating – Grimsby Telegraph". Grimsby Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- E.ON Humber Gateway Project website.

- "World's second largest offshore wind farm opens off coast of Wales". Wales Online. 17 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Public meetings on Gwynt y Mor wind farm – North Wales Weekly News Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- "Dudgeon hits CfD milestone". ReNews. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- BWEA Archived 25 February 2006 at the Wayback Machine. BWEA.

- Trickyweb Ltd. "Dudgeon Wind Farm – Consenting documents". dudgeonoffshorewind.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Eight renewable energy projects approved". BBC News. 23 April 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Dudgeon construction underway". Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "World's first floating wind farm starts generating electricity". BBC. 18 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "Hywind Scotland Pilot Park". statoil.com. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- "'World's largest' floating wind farm gets ok in Scotland". Yahoo News UK. 2 November 2015.

- "Blyth". EDF Renewables.

- "Blyth Offshore Demonstrator Project". 4COffshore. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "Race Bank comes alive". 1 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Offshore Wind News website. Offshorewind.biz (6 July 2012).

- "Cutting-edge Aberdeen offshore wind farm officially opened". 7 September 2018.

- "Consent for Donald Trump row wind farm announced", BBC News, 26 March 2013

- "Kincardine Offshore Wind Farm". www.independent.co.uk. 10 March 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "First Kincardine Floating Wind Turbine Sets Off". 17 August 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Kincardine floating wind project to generate first power next week – News for the Oil and Gas Sector". 7 September 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "First power at Kincardine floating project". Windpower Offshore. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "Floating wind turbines planned off Kincardine coast". BBC News. 16 May 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- "Green light for Aberdeen floater". 9 March 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "Rampion wind farm officially launched at i360 ceremony". Brighton and Hove Independent. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Rampion Offshore Wind Farm". rampionoffshore.com. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- "Scotland's largest offshore wind farm officially opened". BBC News. 29 July 2019.

- OffshoreWIND.biz website. (24 April 2017).

- "First power exported from Beatrice Offshore Wind Farm". 19 July 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- "World's Largest Offshore Wind Farm Fully Up and Running". 30 January 2020.

- "Cable success at Hornsea One". Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- "The world's biggest offshore wind farm, Hornsea 1, generates first power". orsted.com.

- "East Anglia One Now Officially Fully Operational". 3 July 2020.

- Association, Press (17 June 2014). "UK government gives green light to offshore windfarm". the Guardian. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "East Anglia One offshore wind farm plan reduced in size". BBC News. 26 February 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- "Turbine installation complete on East Anglia ONE offshore windfarm". ScottishPower Renewables.

- "First Kincardine foundation makes it to the harbour". 4COffshore. 16 October 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- "Contracts for Difference Second Allocation Round Results" (PDF). UK Gov. 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Giant Triton Knoll offshore wind farm given green light". businessgreen.com. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Triton Knoll Foundations and Export Cables In Place".

- "Moray Offshore Renewables – Home". morayoffshorerenewables.com. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Lamprell Gearing to Send Off First Moray East Jackets". 16 January 2020.

- "Hornsea Offshore Wind Farm (Zone 4) – Project Two". planningportal.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "EDF Group Acquires Troubled 450 Megawatt Neart na Gaoithe Offshore Wind Farm". 4 May 2018. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ScottishGovernment. "ScottishGovernment – News – Consent for offshore wind development". scotland.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "Neart na Gaoithe project enters first phase of offshore construction".

- "Contracts for Difference (CfD) Allocation Round 3: results". 20 September 2019.

- "Government green lights record-breaking Dogger Bank offshore wind farm". businessgreen.com. 17 February 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- "Dogger Bank Creyke Beck". planningportal.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "GE Renewable Energy launches the uprated Haliade-X 13 MW wind turbine for the UK's Dogger Bank Wind Farm". GE. General Electric. 21 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- "SSE, Fluor prep for 2019 CfD auction with bigger Seagreen project". Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- "Dounreay Tri – Hexicon". www.hexicon.eu. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Dounreay Trì". 4COffshore. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "Dounreay Tri – Hexicon". www.hexicon.eu. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- "ScottishPower submits plans for 1.2-GW East Anglia III offshore wind farm".

- "National Infrastructure Planning East Anglia THREE Offshore Wind Farm webpage". Offshore Wind. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "ForthWind Offshore Wind Demonstration Project". 4COffshore. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- "Dogger Bank Teesside A&B". planningportal.gov.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- "Inch Cape – 4C Offshore". www.4coffshore.com. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "Judge overturns offshore wind farms block". BBC News. 16 May 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "No more than 72 turbines off Scottish coast in new Inch Cape design".

- "Moray West gets the green light". 4COffshore. 17 June 2019.

- "Moray West". 4COffshore. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- "Display panels for Dogger Bank Teesside A&B" (PDF). Forewind. 2013.

- "GE Renewable Energy's Haliade-X turbines to be used by Dogger Bank Wind Farms | GE News". www.ge.com.

- . planning inspectorate https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/projects/eastern/hornsea-project-three-offshore-wind-farm/. Retrieved 1 January 2021. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - . Orsted https://hornseaproject3.co.uk/about-the-project#0. Retrieved 2 June 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - . Orsted https://orstedcdn.azureedge.net/-/media/www/docs/corp/uk/hornsea-project-three/faq/hornsea-project-three-faq_august-2018_.ashx?la=en&hash=E6B7688B63315B02F46DF1787FEEDF305BF2381C&rev=d4c960c61a3a4c5daeb21daf00d2ca65. Retrieved 2 June 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - . Orsted https://hornseaprojects.co.uk/hornsea-project-four/about-the-project-4#7. Retrieved 2 June 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - . Orsted https://orstedcdn.azureedge.net/-/media/www/docs/corp/uk/hornsea-project-four/faq/hornsea-project-four-faq-september.ashx?la=en&rev=f011d2efe4494d1ba6cdaa6dc5ee8e7d&hash=1C3A5680EAC758CD5E8A809F5B55BD1B. Retrieved 2 June 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - https://infrastructure.planninginspectorate.gov.uk/projects/eastern/norfolk-vanguard/. Retrieved 3 July 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - https://group.vattenfall.com/uk/what-we-do/our-projects/vattenfallinnorfolk/norfolk-boreas. Retrieved 3 July 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Aspinall, Shell. "Dorenell's 59 Turbines Delivered!". Collett & Sons. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Delabole Village website. Delabole.com.

- SSE Hadyard Hill website. Scottish-southern.co.uk.

- article on opening of Scout Moor wind farm. BBC News (25 September 2008).

- "Turley Associates Slieve Rushen Project website". Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- Whitelee wind farm website. Whiteleewindfarm.co.uk.

- Department of Energy and Climate Change (2010), Digest of United Kingdom energy statistics (DUKES) 2010, Stationery Office, ISBN 978-0-11-515526-0, retrieved 7 June 2011

- "Embedded and Renewable Generation". 2009 Seven Year Statement. National Grid. 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- BWEA News – Decision makers must heed Stern warning on climate change. Bwea.com (2 March 2007).

- Harvey, Fiona (27 February 2012). "Has the wind revolution stalled in the UK?". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 5 April 2012.